Chapter 2

Our Amateur Beginnings

When I was in junior high school, I had to stay home for several weeks because of a contagious illness. My father had an old office ¼″ audiotape machine with a simple omnidirectional microphone that was really only intended for recording close-proximity voices. In a matter of days I was swept into a fantasy world of writing and recording my own performances like the radio shows I had heard. I played all the parts, moving about the room to simulate perspective, making a wide variety of sound effects and movements to conjure up mental images of Detective Ajax as he sought out the bad dealings of John J. Ellis and his henchmen.

I opened and closed doors, shuffled papers, moved chairs about. My parents had an antique wood rocking chair that creaked when you sat in it. I ignited a firecracker to make gunshots and threw a canvas sack of potatoes on the floor for body falls. It wasn't until the recording tape broke, however, and I took up scissors and tape to splice it back together, that I got the shock of my life. After I repaired the break, I wondered if I could cut and move around prerecorded sounds at will. This could remove the unwanted movement sounds—trim the mistakes and better tighten up the sound effects. Years later I came to appreciate how the early craftspeople in the infancy of motion pictures must have felt when they first tried moving shots and cutting for effect rather than repair. The power of editing had sunk in.

Late at night I would crawl under the covers, hiding the audiotape machine under the blankets, and play the sequence over and over. Though I would be embarrassed by its crudeness today, it was the germination and the empowerment of sound and storytelling for me. Clearly I had made a greater audio illusion than I ever thought possible.

Several years later I joined the high school photography club. That was when I became visually oriented. The exciting homemade radio shows became just fond memories after I found a fateful $20 bill hidden in a roll-top desk at a thrift shop. I had been eyeing a black, plastic Eastman Kodak 8-mm spring-wind camera that could be ordered from the Sears catalog for $19.95. Guess how I spent the $20?

The camera had no lens, only a series of holes in a rotatable disk that acted as f-stops. The spring-wind motor lasted only 22 seconds, so I carefully had to plan how long the shots could be—but with it my life changed forever. The visual image now moved, and with a little imagination I quickly made the camera do dozens of things I'm sure the designer and manufacturer never intended for it to do.

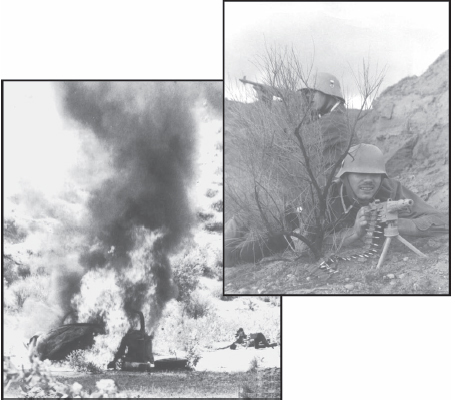

Figure 2.1 Amateur high school film The Nuremberg Affair. Warren Wheymeyer and Chris Callow act as German soldiers in a firefight scene with French resistance fighters. (Photos by David Yewdall.)

Later that year I was projecting some 8-mm film on the bedroom wall for some of my high school friends who had been a part of the wild and frenzied film shoot the previous weekend. We had performed the action on an ambitious scale, at least for small-town high school students. We shot an action film about the French Resistance ambushing a German patrol in a canyon, entitled The Nuremberg Affair. We carefully buried several pounds of black powder in numerous soft-drink cups around the narrow flatland between two canyon walls of a friend's California ranch, and a couple of dozen of us dressed in military uniforms.

A hulk of a car had been hauled up from the junkyard, a vehicle identical to the operating one serving as the stunt car. We carefully filmed a sequence that gave the illusion of a French Resistance mortar shell hitting the staff vehicle, blowing it up, and sending a dozen soldiers sprawling into the dirt and shrubs of the wash. In the next set-up, they rose and charged the camera. My special effects man, sitting just off-camera, ignited each soft-drink “mortar-cup” charge, sending a geyser of dirt and debris into the air. The high school stunt actors had fun as they jumped and flung themselves about, being invisibly ambushed by the off-screen French underground.

A week later we huddled together to watch the crudely edited sequence. It happened that my radio was sitting on my bedroom windowsill and a commercial for The Guns of Navarone burst forth. Action-combat sound effects and stirring music were playing while the segment of our amateur mortar attack flickered on the bedroom wall. Several of us reacted to the sudden sensation—the home movie suddenly came alive, as many of the sound effects seemed to work quite well with the visual action. That year I won an Eastman Kodak Teenage Award for The Nuremberg Affair. The bug had really bitten hard.

Up until that time, I had been making only silent films—with an eye toward the visual. Now my visual eye grew a pair of ears. Of course, sound did not just appear on the film from then on. We quickly learned that there seemed to be much more to sound than simply having the desire to include it as part of the performance package. It also did not help much that back in the 1960s no such thing existed as home video cameras with miniature microphones attached. Super-8-mm was offering a magnetic striped film, but any kind of additional sound editing and mixing were very crude and difficult.

We did make two amateur short films with a separate ¼″ soundtrack. Of course no interlocking sync mechanism existed, and the only way to even come close was to use a ¼″ tape recorder that had a sensitive pause switch. I would sit and carefully monitor the sound, and, as it started to run a little faster than the film being projected, I would give the machine little pauses every so often, helping the soundtrack jog closer to its intended sync. All of this seemed very amateurish and frustrating. Yet as difficult as non-interlocking sound gear was to deal with, it had become essential to have a soundtrack with the picture.

EARLY APPLICATIONS

My first real application of custom sound recording for public entertainment occurred when I was given the sound effects job for Coalinga's West Hills College presentation of the play Picnic. Sound effect records of the day were pretty dreadful, and only the audiophiles building their own Heathkit high-fidelity systems were interested more in authentic realism and speaker replication than in entertainment expression.

As you work increasingly in sound, you will quickly learn the difference between reality sound and entertainment sound. I can play you a recording of a rifle butt impacting the chin of a man's skull. It is an absolutely authentic recording, yet it sounds flat and lifeless. On the other hand, I can edit three carefully chosen sound cues together in parallel and play them as one, and I promise that you will cringe and double over in empathetic pain. Therein lies the essential difference between realism, which is an actual recording of an event, and a sound designer's version of the same event, a combination brew that evokes emotion and pathos.

I soon gave up trying to find prerecorded sound effects and set out to record my own. I did not know much about how to record good sound, but I was fortunate to have acquired a monaural Uher model 1000 ¼″ tape deck that I used for my amateur 16-mm filmmaking. I talked a local policeman into driving his squad car out of town and, from a couple of miles out, drive toward me at a hasty rate of speed with his siren wailing away. I recorded doorbells and dogs barking, as well as evening cricket backgrounds. At that time I was not at all interested in pursuing a career in sound, and actually would not take it seriously for another 10 years, yet here I was practicing the basic techniques I still use today.

While making a documentary film about my hometown, we had gotten permission to blow up an oil derrick on Kettleman Hills. We had shot the sequence MOS (without sound) and decided later we needed an explosion sound effect. I did not know how to record an explosion, nor did I think the explosions we made for our films would sound very good; how they looked and how they sounded in reality were two entirely different things.

I decided to experiment. I discovered that by wrapping the microphone in a face towel and holding it right up next to my mouth I could mimic a concussionary explosion with my lips and tongue, forcing air through my clinched teeth. The audio illusion was magnificent!

A few years later a couple of friends and my father joined me in making a fundraising film for Calvin Crest, a Presbyterian church camp in the Sierra Nevada mountains. It was our first serious attempt at shooting synchronous sound while we filmed. We had built a homemade camera crane to replicate Hollywood-style sweeping camera moves in and among the pine trees. The 18-foot reach crane was made of wood and used precision ball-bearing pillow-blocks for rotation pivots.

We never actually had a synchronous motor on the camera, so during the postproduction editorial phase of the project I learned how to eyeball sync. I discovered that a non-sync motor means that the sound recording drifts. I painstakingly resynced the sound every few seconds as the drift increased. Becoming extremely observant, I looked for the slightest movement and identified the particular sounds that must have come from that movement. I then listened to the track, found such audible movements, and lined the sound and action into sync. Conversely, I learned to take sound with no synchronous relationship at all with the image that I had, and, through clever cuts and manipulation, made the sound work for moments when we had no original sound recording at all.

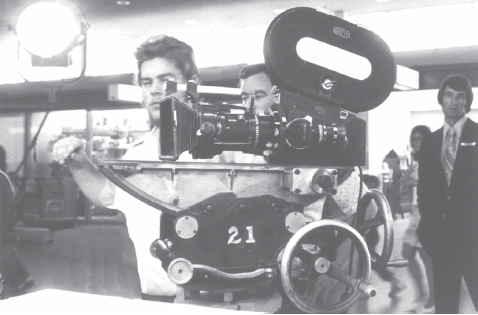

I am the first to admit how bizarre and out of place the camera set-up in Figure 2.2 appears. Most filmmakers starting out will tell you (especially if you have no money and must work “poor-boy” style) that you must learn how to mix and match various kinds of equipment together—to make do when money to rent modern camera and sound equipment is scarce. In the photo, I am standing just to the side of the lens of the 16-mm Arriflex as I am directing the action. My partner, Larry Yarbrough, is standing just behind me, coordinating the lighting and handling the audio playback of prerecorded dialog, as we did not record very much sync sound back then. Our actors listened to a prerecorded tape played back through a speaker off-screen as they mouthed the dialog, much the same way musicals are filmed to playback. Like I said, you have to make do with what you have. It certainly was not a convenient camera platform, but boy was it rock steady!

Figure 2.2 I'm standing just behind the lens of a 16-mm Arriflex sitting atop the giant 100 Moey gear head specially designed for the giant MGM 65-mm cameras. This particular gear head was one of the set used in William Wyler's Ben-Hur. (Photo by David Yewdall.)

Of course, our soundtrack was crude by professional audio standards today, but for its day and for where I was on the evolutionary scale of experience, Calvin Crest had opened a multitude of doors and possibilities to develop different ideas because of new, empowering, creative tools then in hand. With what I had learned through the “baptism by fire” of doing, I could take a simple 35-mm combat Eymo camera with a spring-wind motor and an unremarkable ¼″ tape recorder with absolutely no sound sync relationship between them and, if I had the will to do so, I could make a full-length motion picture with both perfectly synchronized sound, and depth and breadth of entertainment value. I was, and still am, limited only by my own imagination—just as you are.

INTERVIEW WITH BRUCE CAMPBELL

Bruce Campbell is probably best known and recognized both for his grizzly cult starring role in the Evil Dead trilogy as well as his title-starring role on the television series The Adventures of Brisco County Jr. When it comes to sound, Bruce is one of the most passionate and audio-involved actor-director-producers I have ever met and had the great pleasure to work alongside.

Bruce began making amateur movies with his high school buddies Sam Raimi (who went on to direct pictures like Crimewave and Darkman, as well as the cult classics Evil Dead, Evil Dead 2, and the ultimate sequel Army of Darkness) and Rob Tapert (producer of movies and television shows). They grew up just outside of Detroit, where they spent increasingly more time creating their first amateur efforts. Bruce remembers:

Figure 2.3 Bruce Campbell, cult star of the Evil Dead trilogy, star of The Adventures of Brisco County Jr., and director and recurring guest star in the number one syndicated Hercules: the Legendary Journeys and Xena: Warrior Princess.

Originally, we worked with regular 8-mm film and a little wind-up camera. The film was 16-mm in width. You would shoot one side, which was 50 feet long, then flip the roll over and expose the other side. You sent it to the lab and they developed it and slit it in half for you.

Of course, we shot those films silent; at least, as we know and understand synchronous sound recording today. Our friend, Scott Spiegel, had a cassette recorder, and he had recorded our dialog as we shot the film. Of course, there was nothing like what we have today with crystal sync and timecode. We just recorded it to the cassette, and Scott would keep careful track of the various angles and takes and re-record/transfer them later as close as he could to the final-cut 8-mm film.

Scott would also record sound effects and backgrounds, many of them from television broadcasts of Three Stooges films. The nice thing about the Stooges was that they didn't have any music during the action scenes, just dialog and loud sound effects. Scott would have all the sound effects he intended to use lined up on one cassette tape like a radio man would set up his cue list and have his sound effect source material at the ready.

We would get in a room and watch the cut 8-mm picture, then Scott would roll the original dialog cassette, playing the sound through a speaker. Scott would play the second cassette of sound effects at precise moments in the action against the dialog cassette, and we would stand around and add extra dialog lines that we had not recorded when we shot the film to begin with. All this time, Scott was re-recording the collage of speaker playback sound and our new live dialog performances onto a new cassette in a crude but effective sound mix.

It was kind of like doing live radio as we were injecting sound effects, looping dialog and mixing it all at once, the difference being that we had to keep in sync to the picture. The real trick was Scott Spiegel mastering the pause button to keep on top of the sync issues.

Scott was the master of this so we let him do it. We had a vari-speed projector, and Scott had made marks on the edges of the film that only he could see during a presentation so that he could tell how out-of-sync the cassette playback was going to be; then he would adjust the projector a little faster or a little slower to correct the sync. Sometimes Scott would have to fast-forward or rewind the cassette real quick in order for the playback to be right. You could hear the on and off clicks in the track, but we didn't care—after all, we had sound!

We would test our films at parties. If [we] could get people to stop partying and watch the movie, then we knew we had a good one. We made about 50 of these short movies, both comedies and dramas.

Then we moved up to Super-8-mm, which had a magnetic sound stripe on it so you could record sound as you filmed the action. The quality of the sound was very poor by today's standards, but at the time it was a miracle! You could either send your Super-8 film out for sound striping (having a thin ribbon of magnetic emulsion applied to the edge of the film for the purposes of adding a soundtrack later), or you could buy Super-8 film with a magnetic sound stripe on it.

There were projectors that had sound-on-sound, where you had the ability for one attempt to dub something in over the soundtrack that was already on the film. Say the action in your Super-8-mm film has two guys acting out a shootout scene, and the first actor's line, “Stick ′em up!” was already on the film. Reacting to the first guy, the second actor turned, drew his pistol, and fired, which of course is a cap gun or a quarter-load blank. If you wanted a big sound effect for the gunshot, using the sound-on-sound technique, you would only have one chance to lay a gunshot in. If you did not record it in correctly or close enough sync, then you wiped out the actor's voice and you would have to then loop the actor saying “Stick ′em up!” all over again, which on Super-8-mm film was going to be extremely difficult at best.

On the original Super-8-mm projectors you could only record on the main magnetic stripe, but when the new generation of projectors came out you could record on the balance stripe [a thin layer of magnetic emulsion on the opposite side of the film from the primary magnetic soundtrack to maintain an even thickness for stability in film transport and being wound or rewound onto a film reel]. This allowed us to record music and sound effects much easier by utilizing the balance stripe as a second track instead of messing up the original recorded track that had been recorded in sync when we originally filmed the sequence.

Our postproduction supervisor was the lady behind the counter at K-Mart. She would see us coming and say, “Okay fellas, whad'ya got now?” Whether it was developing or sending our cut film back to have a new balance stripe applied to the edge so we could record a smoother music track, she was our lab.

Sam Raimi did a 50-minute film called The Happy Valley Kid, the story of a college student driven insane, that he shot on the Michigan State University campus with real professors and real students, and Rob Tapert portrayed the Happy Valley Kid. The film cost about $700 to make, and they showed it at midnight showings to students. The kids loved to see the film because they got to see The Happy Valley Kid blow away all the evil professors. Sam actually got the professors to allow themselves to be shot and gunned down on film. They made about $3,500 bucks on it—probably some of the best vicarious therapy that frustrated students could sit down and enjoy without going postal themselves.

We actually raised the money to make a movie based on a Super-8-mm film that we had shot as a pilot, as a device to show investors the kind of motion picture that we were going to make and convince them to invest money in us. Sam Raimi had been studying some occult history in humanities class when his prolific and overactive imagination gave him a middle-of-the-night vision. I personally think it stemmed from something he had eaten for dinner earlier in the evening, but a lot of Sam's subsequent script was based on the Necronomicon stuff that came up in class.

We made our best Super-8-mm double-system sound film yet. We had acquired much better sound effects, using a ¼″ reel-to-reel deck whenever we could get our hands on one. We would carefully patch directly in from a stereo system so we could control the quality of the sound transfer for music or sound effects. By this time we had gotten much better about understanding recording levels, even the concept of distortion and how to avoid it as much as possible. By the time we raised the money to make the first Evil Dead film, we were much better prepared, at least knowing that we wanted a really good and interesting sound, and we knew that before we went out to film the picture.

When we finished cutting the picture of Evil Dead and we were ready for the postproduction sound process, we went to Sound One in New York City with Elisha Birnbaum. We immediately discovered that, from an audio point-of-view, it was a whole new ball game and that we weren't in Kansas anymore. We had a lot of bones and blood and carnage in the film, so Sam and I would go to a market and we would buy chickens and celery and carrots and meat cleavers and that sort of stuff to use for recording. Elisha was a one-man show. He would roll the picture, then run in and perform Foley cues on the stage; then he would run back into the back booth to stop the system.

Our supervising sound editor was Joe Masefield. Joe was extremely detail oriented. Each sound effect had a number, based on the reel it belonged to, whether it was a cue of Foley or a sound effect or dialog or whatever. He sat there in the recording booth and told us what we needed to perform. For Sam and me, we were still kind of lagging from our amateur days of how to make sounds because we would argue who could make the best gravy-sucking sound and who would twist and cut the celery while the other guy was making awful slurping noises. We heard later that it took weeks for them to get the smell of rotting cabbage and chicken out of their Foley stage.

Mel Zelniker was the mixer. He was really good for us, as he brought us up out of our amateur beginnings and helped to point us into a more professional way of doing things. Mel would teach us stage protocol and procedure through example. Sam stepped off the stage for a drink of water and returned just as Mel mixed the sound of a body being flopped into a grave. Sam asked Mel if he could mix the body fall a little hotter. Mel played the game of not touching the fader pot to see if we noticed—you know, the way mixers can do. It was so embarrassing because then he would ask Sam what he thought after he supposedly mixed it hotter, and Sam would say he liked it, and Mel would huff and reply, “I didn't touch it.”

Then Mel would run it again, only this time he would push the volume until it was obviously over the top. He'd ask us, “How was that?” We'd nod our heads, ‘That was fine, just fine.’ Mel snapped back at us, “It's too loud!,” and he would run it again and bring the volume back down. Mel knew we were a couple of hicks from Detroit, but in his own way he was trying to teach us at the same time.

At one point I asked him if he could lower one of my loop lines. Mel turned on me, “What's the matter, you embarrassed?!” I didn't know what to say. “Yeah, I am actually.” Mel shrugged, “Okay, I just wanted to clear that up,” and he would continue mixing. He would mix one long pass at a time, and we actually got a weird effect out of it. Their equipment had an odd, funky problem with one of the fader pots; it left an open chamber, which created a strange airy-like sound that, if he just moved that pot up a little, created the best eerie ambience for us. It was not a wind; it was almost like you were in a hollow room. That was our gift. Every so often either Sam or I would say, “Hey, stick that ambience in there!” Mel would frown, “You guys! You're usin’ it too much!”

It wasn't until after the mix that Mel and his engineer discovered that a rotating fan motor vibration was being conducted through hard point contact that was leaking into the echo chamber, a clever technique that Mel quietly tucked away for future use. For our first real movie we got several gifts. Another one happened in the middle of the night when we were shooting the film in Tennessee. Sam was awakened by a ghostly wind that was coming through the broken glass window in his room. He ran down the hall and dragged the sound guy out of bed to fire up the Nagra to record it. That airy tonal wind became the signature for the film. The fact is, there are gifts around you all of the time, whether you are shooting or not—the trick is for you to recognize the gifts when they happen and be versatile enough to take advantage of them. That's when the magic really happens.

Several years later, the trio made the sequel, Evil Dead 2. It was their first opportunity to work with the sound in a way that they could prebuild entire segments before they got to the rerecording dubbing stage. They had progressed from the Moviola, where their sound had been cut on 35 mm mag stripe and fullcoat to 24 track using videotape and timecode to interlock the sync between picture (on videotape) and soundtrack (being assembled on 24-track 2″ tape). Bruce Campbell not only reprised his character of Ash from the original Evil Dead, but he also handled the postproduction sound chores. He started by insisting on walking his own footsteps in the film, and one thing led to another. The attention to detail became an obsession.

We cut the picture for Evil Dead 2 in Ferndale, Michigan, in a dentist's office. I asked the manager of the building to give me one of the offices for a month that was in the center of the building, not near the front and not near the back. I didn't want to contend with traffic noise. We got the deepest part of an office that was well insulated by the old building's thick walls. I asked a sound engineer by the name of Ed Wolfman, who I would describe in radio terms as a tonemeister, a German term for a master craftsperson mixer or recordist, to come look at this huge plaster room we had. I told him that I wanted to record wild sound effects in this room, and how could I best go about utilizing the space acoustically?

We built a wooden section of the floor, then built a downscaled replica of the original cabin set from the film. We needed the floor to replicate the correct hollowness that we had from the original cabin because we had a lot of scuffling, props falling, footsteps—a lot of movement that would have to fold seamlessly into the production recording. Ed told us to build one of the walls nonsymmetrical—angle it off 10 percent, 20 percent—so we put in a dummy wall that angled in, so that the sound would not reflect back and forth and build up slap and reverb. We did the foam-and-egg-carton routine by attaching them in regimented sheets around on sections of the wall for trapping and controlling sound waves.

While Sam [Raimi] was in a different part of the office building picture-cutting the film, I cranked up my word processor and built an audio event list—a chronological list of sounds that were going to be needed for the picture that we could replicate in our downsized cabin stage and custom record them. I guess you would consider this wild Foley. These sound cues were not performed while we watched picture or anything. We would review the list and see “things rattle on a table.” Okay, let's record a bunch of things rattling on a table, and we'll record a number of variations. “Table falls over”—we recorded several variations of a table falling over, etc.

This one office of the dentist building had water damage from the radiators, and we thought, “Let's help ′em out just a little bit more.” So I took an axe and recorded some really good chops and scrapes. It is so hard to find that kind of material in just that kind of condition to record. It was so crunchy, and it had these old dried wood slats from the 1920s—it was perfectly brittle. One little chop led to another. “Keep that recorder rolling!” I'd swing the axe, smashing and bashing. I felt guilty about what I was doing to the ceiling, but the recordings were priceless. It is just impossible to simulate that kind of sound any other way!

What resulted was Bruce and Sam returning to Los Angeles for formal postproduction sound-editorial work with a wealth of custom-recorded material under their arms, meticulously developed over weeks of study and experimentation.

Bruce Campbell continued his acting and directing career in the states and abroad, spending much of his time in New Zealand, writing, directing, and even appearing in the Xena and Hercules television series, as well as developing theatrical motion picture projects of his own.

Bruce admits that sound has had a tremendous effect on his professional career. It has made him a better storyteller as well as a more creative filmmaker, but he admits he misses having the luxury of the hands-on participation in custom recording and developing soundtracks. Listen to the Xena and Hercules television shows. The roots of their sound design go all the way back to those early days in Detroit when Bruce and his friends struggled not only to keep an audio track in sync with the visual image but also to create something extraordinary.

DEVELOP YOUR EYES AND EARS TO OBSERVE

I do not mean for this to sound egotistical or pompous, but, shortly after you finish reading this book, most of you will notice that you see and hear things differently than ever before. The fact is, you have always seen and heard them—you have just not been as aware of them as you now are going to become. This transition does not happen all at once. It does not go “flomp” like a heavy curtain—and suddenly you have visual and audio awareness. You probably will not be aware the change is taking place, but, several weeks or a few months from now, you will suddenly stop and recognize that your sensory perceptions have been changing. Some of you will thank me—others will curse me. Some people become so aware that they find it incredibly hard to watch movies or television again. This is a common side effect. It is really nothing more than your awareness kicking in, along with a growing knowledge of how things work. Be comforted to know that this hyperawareness appears to wear off over time. In fact, it actually does not.

Your subconscious learns to separate awareness of technique and disciplines from the assimilation of form and storytelling, the division between left-brain and right-brain jurisdictions. Regardless of whether you are aware of it, you learn how to watch a motion picture or television program and to disregard its warts and imperfections. If you did not learn this ability, you probably would be driven to the point of insanity (of course, that might explain a few things in our industry these days).

As for myself, I remember the exact moment the figurative light bulb went on for me. I was sitting in my folks’ camper, parked amid the tall redwood trees near the Russian River in northern California, reading Spottiswood's book Film and Its Techniques. I was slowly making my way through the chapter dealing with the film synchronizer and how film is synced together when kapow!—suddenly everything I had read before, most of which I was struggling to understand conceptually, suddenly came together and made perfect sense. Those of you who have gone through this transition, this piercing of the concept membrane, know exactly to what I'm referring. Those of you who have not experienced it are in for a wonderful moment filled with a special excitement.

PROTECT YOUR MOST PRECIOUS POSSESSIONS

The world has become a combat zone for one of your most precious possessions: your ability to hear. During everyday activities, you are constantly in close proximity with audio sources with the potential to permanently impair your future ability to hear. Unfortunately, you probably give none of these sources a passing consideration.

If you hope to continue to see and hear the world around you clearly for a long time, then let go of any naive misperception that those senses will always, perfectly, be with you. This book does not address the everyday dangers and potentially harmful situations regarding loss of or impairment to your eyesight because it was not written with authority on that topic. As for protecting your ability to hear clearly, one of the most common and sensory-damaging dangers is distortion. This is not the same as volume. Your ears can handle a considerable amount of clearly produced volume; however, if the audio source is filled with distortion, the human ear soon fatigues and starts to degenerate. A common source of distortion is the device known as the “boom box.” Car radios are another source of overdriven audio sources, played through underqualified amplifiers and reproduced by speakers setting up a much higher distortion noise to clear signal ratio, which begins to break down the sensitivity of your audio sensors.

In other scenario, you attend a rock concert. After a few minutes, you start to feel buzzing or tingling in your ears. This is the first sign that your ears have become overloaded and are in danger of suffering permanent and irreparable damage.

The audio signal in question does not have to be loud, however. Many television engineers and craftspeople who work in close proximity to a bank of television monitors for long periods of time discover that they have either lost or are losing their high-end sensitivity. Many of these individuals cannot hear higher than 10-kHz.

Sometimes I had groups of students from either a high school or college come to the studio to tour the facility and receive an audio demonstration. During the demos, I would put a specially made test-tone tape on a DAT machine and play a 1-kHz tone, which everyone could hear. They would see signal register accordingly on the VU meter. I would then play them 17-kHz. Only about half could hear that, but they could all see the signal on the VU meter. I would then play them 10-kHz with the same strength on the VU meter. By this time, several students inevitably would be in tears; they had lost the ability to hear a 10-kHz tone so early in life.

After asking one or two poignant questions regarding their daily habits of audio exposure, I knew the exact culprit. Almost no demonstration strikes home more dramatically than this, forcing a personal self-awareness and disallowing denial. The students could fib to me about whether they could hear the signal, but they themselves knew they could not hear it; the proof was in front of them, the visual affirmation of the strong and stable volume on the VU meter for all to see. I plead with you, before it is too late. Become aware of the dangers that surround you every day, understand what audio fatigue is, realize that length of duration to high decibels and audio distortion results in permanent hearing loss, either select frequency or total.

Someone asked me once, “If you had to choose between being blind or deaf, which would you choose?” I did not hesitate; I chose blind. As visual a person as I am, I could not imagine living in a world where I could not enjoy the sweet vibrant sound of the cello, or the wind as it moves through the pine trees with the blue jays and morning doves, or the sensual caress of the whispered words from my wife as we cuddle together and share the day's events. So protect your most precious of personal possessions—your eyes and ears.