Chapter 4

Success or Failure

Before the Camera Even Rolls

“If you prep it wrong, you could find yourself

in a win-win-lose situation.”

The success or disappointment of your final soundtrack is decided by you, before the cameras even roll, even before you commence preproduction!

The above 22 words constitute perhaps the single most important truth in this book. It is so important that I want you to read it again. The success or disappointment of your final soundtrack is decided by you, before the cameras even roll, even before you commence preproduction!

You not only must hire a good production sound mixer along with a supreme boom person, you must know the pitfalls and traditional clash of production's form and function to “get it in the can” and on its way to the cutting room. You must know how to convey the parameters and needs to the nonsound departments, which have such a major impact on the ability of the sound-recording team to capture a great production dialog track. If you do not allow enough money in the lighting budget to rent enough cable, you do not get the generators far enough away from the set, resulting in continuous intrusion of background generator noise. This isn't so bad if you are filming in bustling city streets, but it certainly does not bode well if you are filming medieval knights and fair maidens prancing around in a Middle Ages atmosphere. Regardless of the period or setting of the film, unwanted ambient noises only intrude on the magic of production performances.

In addition, you must know about the dangers and intrusions of cellular phones and radio-control equipment when working with wireless microphones. You must know how to budget for multiple microphone set-ups using multiple boom persons and multiple cameras. You must understand the ramifications of inclement weather and the daily cycle of atmospheric inversions that can cause unpredictable wind-buffet problems during an exterior shoot.

Figure 4.1 Sound boom operators must get into the middle of any action being created on the screen: from hurricane-driven rain, to car-chase sequences, to dangerously moving equipment. Here, two boom operators bundle up on padded-boy wraps, gauntlets, and machinist masks to protect themselves from flying bits of rock and debris, while still striving to capture the best microphone placement possible. (Photo by Ulla-Maija Parikka.)

With today's advancements in wind-control devices and numerous new mounts and shock absorbers, production mixers capture recordings with greater clarity and dynamic range than ever before, but they can't do it alone. Such a recording equipment package does not come free, included in the daily rate of the craftsperson. You must allow enough money in the equipment rental package, whether it is rented from an audio facility or whether it is the property of the sound person utilizing his or her own gear.

It is important that you consult with your director of photography. After careful consideration of the photographic challenges you must overcome, you will soon know what kinds of cameras you should rent. Three unblimped Arri-III cameras grinding away as they shoot the coverage of three men lounging in a steam room speaking their lines pose some awful sound problems—that is, if you hope to have a production track to use in the final mix! The motors of three unblimped cameras reverberating off hard tile walls will not yield a usable soundtrack. Do you throw up your hands and tell the sound mixer to just get a guide-track, conceding that you will have to loop it later in postproduction? You can, but why should you?

Of all the films I contracted and supervised, I only remember three pictures where I was brought in before the producer commenced preproduction to advise and counsel during the budgeting and tactical planning, the desired result being a successful final track.

John Carpenter set me as the supervising sound editor for The Thing a year before he started shooting. I helped advise and consult with both John and his production mixer, Tommy Causey, before they even left for Alaska, where they shot the “Antarctica” location sequences. By this time, I had already done two of John's pictures, on both of which Tommy had served as production mixer. Tommy used to ask if we could get together for coffee and discuss the upcoming shoot. It gave me a great opportunity to ask him to record certain wild tracks while he was there. He would tell me how he intended to cover the action and what kinds of microphones he intended to use. It never failed that after the cast and crew screening Tommy would always tell me that he really appreciated the coffee and conversation, as he would not have thought of something that I had added or that I said something that stimulated his thinking, which led to ingenious problem solving.

While John and his team shot up north in the snow, I saw dailies at Universal and went out into the countryside on custom-recording stints to begin developing the inventory of specialty sounds that were needed, months before sound teams were usually brought onto a picture. This preparation and creative foreplay gave us the extra edge in making an exciting and memorable soundtrack. (Oddly enough, the bone-chilling winds of The Thing were actually recorded in hot desert country a few miles northwest of Palm Springs.) To this day, I have been hired for other film projects because I did the sound for The Thing.

A couple years later, Lawrence Kubik and Terry Leonard sat down with us before they commenced preproduction on their action-packed anti-terrorist picture Death Before Dishonor. They needed the kind of sound of Raiders of the Lost Ark, but on a very tight budget. Intrigued by the challenge to achieve a soundtrack under such tight restrictions, coupled with Terry Leonard's reputation for bringing to the screen some of the most exciting action sequences captured on film today—sequences that always allowed a creative sound designer to really show off—I decided to take it on.

To avert any misunderstandings (and especially any convenient memory loss months later, during postproduction), we insisted that the sound-mixing facility be located where we would ultimately re-record the final soundtrack. We further insisted that the final re-recording mixers be set and that all personnel with any kind of financial, tactical, or logistical impact on the sound process for which I was being held singularly responsible meet with me and my team, along with the film's producers. Using a felt-tip marker and big sheets of paper pinned to the wall, we charted out a battle plan for success.

Because we could not afford to waste precious budget dollars, we focused on what the production recording team must come back with from location. We gave the producers a wish list of sounds to record in addition to the style of production recording. Because of certain sequences in the script where we knew the dialog would later be looped in postproduction for talent and/or performance reasons, we suggested they merely record a guide-track of the talent speaking their lines for those specific sequences. The production sound mixer should concentrate on the nearly impossible production sound effect actions taking place in nearly every action set-up, getting the actors to speak their lines as individual wild tracks whenever he could.

Hundreds of valuable cues of audio track came back, authentic to the Middle Eastern setting and precisely accurate to the action. This saved thousands of dollars of postproduction sound redevelopment work, allowing the sound-design chores for high-profile needs, rather than track building from scratch.

Because we could not afford nearly as much Foley stage time as would have been preferred, we all agreed as to what kind of Foley cues we would key on and what kind of Foley we would not detail but could handle as hard-cut effects. We placed the few dollars they had at the heart of the audio experience. This included making the producers select and contract with the re-recording facility and involving the re-recording mixers and facility executive staff in the planning and decision-making process. Each mixer listened to and signed off on the style and procedure of how we would mount the sound job, starting with the production recordings through to delivering the final-cut units to the stage to be mixed into a final track. We charted out the precise number of days, sometimes even to the hour, that would be devoted to individual processes. Also, we set an exact limit to the number of channels that would be used to perform the Foley cues, which mathematically yielded a precise amount of 35-mm stripe stock to be consumed. With this information, we confidently built in cap guarantees not to be exceeded, which in turn built comfort levels for the producers.

We laid out what kind of predubbing strategy would be expected, complete and proper coverage without undue separations, specifying a precise number of 35-mm fullcoats needed for each pass.

Mathematically and tactically, both the facility budget and dubbing schedule unfolded forthwith. It was up to us to do our part, but we could not, and would not be able to, guarantee that we could accomplish the mission unless everyone along the way agreed and signed off to his or her own contribution and performance warranty as outlined by the various teams involved. Everyone agreed, and 14 months later the Cary Grant Theatre at MGM rocked with a glorious acoustical experience, made possible by the thorough collaboration of problem-solving professionals able to lead the producers and director into the sound mix of their dreams.

In a completely different situation, I handled the sound-editorial chores on a South-Central action picture. We had not been part of any preplanning process, nor had we any say on style and procedure. As with most jobs, my sound team and I were brought onboard as an afterthought, only as the completion of picture editorial neared. We inherited a production track that was poorly recorded, with a great deal of hiss, without thought of wild-track coverage. To further aggravate the problem, the producer did not take our advice and loop what was considered to be a minimum requirement to reconstruct the track. The excuse was that the money was not in the budget for that much ADR. (This is a typical statement, heard quite often, almost always followed several months later by a much greater expenditure than would have been needed had the producers listened to and taken the advice of the supervising sound editor.)

The producer walked onto Stage 2 of Ryder Sound as we commenced rehearsing for a final pass of reel 1. He listened a moment, then turned and asked, “Why are the sound effects so hissy?” The effects mixer cringed, as he was sure I would pop my cork, but I smiled and calmly turned to the head mixer (who incidentally had just recently won an Academy Award for Best Sound). “Could you mute the dialog predub please?” I asked.

“Sure,” he replied as his agile fingers flicked the mute button. The entire dialog predub vanished from the speakers. Now the music and sound effects played fully and pristinely, devoid of any hiss or other audio blemishes. The producer nodded approval, then noticed the absence of dialog from the flapping lips. “What happened to the dialog track?”

I gestured to the head mixer once more. “Could you please unmute the dialog predub?”

He flipped off the mute button, and the dialog returned, along with the obnoxious hiss. The producer stood silently, listening intently, then realized. “Oh, the hiss is in the dialog tracks.” He turned to the head mixer. “Can you fix that?”

The mixer glanced up at him, expressionless. “That is fixed.”

This made for more than one inevitable return to the ADR stage as we replaced increasingly more dialog cues—dialog we had counseled the producer to let us ADR weeks earlier. Additionally, more time was needed to remix and update numerous sequences. This experience did much to chisel a permanent understanding between producer and sound supervisor—and a commitment not to repeat such a fiasco on future films. Much to my surprise, the producer called me in for his next picture, which was a vast improvement; but it wasn't until the following picture that the producer and I bonded and truly collaborated in mounting a supreme action soundtrack.

The producer called me in as he was finishing the budget. “Okay, Yewdall, you keep busting my chops every time we do a picture together, so this time you are in it alongside me. No excuses!”

He made it clear that he wanted a giant soundtrack, but did not have a giant budget. After listening to him explain all about the production special-effects work to be done on the set, I told him that we should only record a guide-track. We decided that we would ultimately ADR every syllable in the picture. It would not only give us a chance to concentrate on diction, delivery, and acting at a later time, but also it would eliminate the continual ambience from the center speaker, which often subdues stereophonic dynamics, allowing us to design a much bigger soundtrack. In fact, the final mix was so alive and full that clients viewing dailies in the laboratory's screening facility were said to have rushed out of the theatre and out the back door, convinced a terrorist takeover was in progress. To this day, the producer calls that picture his monster soundtrack—and rightfully so.

UNDERSTANDING THE ART FORM OF SOUND

First, you must know the techniques available to you; many filmmakers today do not. They don't have a background in the technical disciplines; hence, they have no knowledge of what is possible or how to realize the vision trapped inside their heads. This stifles their ability to articulate to their department heads clear meaningful guidance, so they suffocate their craftspeople in abstract terminology that makes for so much artsy-sounding double-talk. They use excuse terms like “Oh, we'll loop it later” or “We'll fix it in post” or, the one I really detest, “We'll fix it when we mix it.” These are, more often than not, lazy excuses that really say “I don't know how to handle this” or “Oops, we didn't consider that” or “This isn't important to me right now.”

Figure 4.2 Pekka Parikka, director of Talvisota: The Winter War, goes over the sound design concepts with Paul Jurälä, the production sound recordist, co-supervising sound editor, and rerecording mixer. Precise planning is vital when working on a very tight budget. (Photo by Ulla-Maija Parikka.)

Sometimes you must step back, take a moment, and do everything you can do to capture a pristine dialog recording. The vast majority of filmmakers will tell you they demand as much of the original recording as possible; they want the magic of the moment. Many times you know that post-sound can and will handle the moment as well if not better than a live recording, so you either shoot MOS (without sound) or you stick a microphone in there to get a guide-track. You must know your options.

THE “COLLATERAL” TERROR LURKS AT EVERY TURN

If you are making an independent film, you must have a firm grip on understanding the process and costs involved, both direct and collateral. Most production accountants can recite the direct costs like the litany of doctrine, but few understand the process well enough to judge the collateral impact and monetary waste beyond the budget line items.

For example, on an animated feature, the postproduction supervisor had called around to get price quotes from sound facilities to layback our completed Pro Tools sessions to 24-track tape. The postproduction supervisor had chosen a facility across town because its rate was the lowest and it did a lot of animation there. When making the inquiry, he had been given a very low rate and had been told that the average time to transfer a reel to 24-track was no more than 30 minutes.

The postproduction supervisor was delighted, and on his scratchpad he scribbled the hourly rate, divided it in half, multiplied it by 4 (the number of reels in the show), and then by 3 (the number of 24-track tapes the supervising sound editor estimated would be needed). That was the extent of the diligence when the decision was made to use this particular facility to do the layback work.

The first layback booking was made for Thursday afternoon at one o'clock. Based on the scanty research (due to the postproduction supervisor's ignorance about the process) and the decision made forthwith, it was decided that, since it would only take 30 minutes per reel to layback, I would not be without my hard drives long enough to justify the rental of what we call a layback or transport drive. A layback or transport drive is a hard drive dedicated to the job of transferring the edited sessions and all the sound files needed for a successful layback; this way, an editor does not need to give up the hard drive and can continue cutting on other reels.

The first error was a lack of communication from the postproduction supervisor and the facility manager in defining what each person meant by a “reel” (in terms of length) and how many channels of sounds each person was talking about regarding the scope of work to be transferred. Each had assumed they were both talking about the same parameters. Sadly, they were not. In traditional film editing terms, a theatrical project is broken down into reels of 1,000 feet or less. This means that the average 90 to 100 minute feature will be Picture Cut on 9 to 10 reels, each running an average of 8 to 10 minutes in length. After the final sound mix is complete, these reels are assembled into “A-B” projection reels (wherein edit reels 1 and 2 are combined to create a projection reel 1AB, edit reels 3 and 4 are combined to create projection reel 2AB, and so forth). Projection reels are shipped all over the world for theatrical presentation. Whether they are projected using two projectors that switch back and forth at the end of reel changeovers, or whether the projectionist mounts the reels together into one big 10,000-foot platter for automated projection, they are still shipped out on 2,000-foot “AB” projection reels.

When the facility manager heard the postproduction supervisor say that our project was four reels long, he assumed that the reels would run approximately 8 to 10 minutes in length, like the reels they cut in their own facility. We were really cutting preassembled AB-style, just like projection reels in length, as the studio had already determined that the animated feature we were doing was a direct-to-video product. Therefore, our reels were running an average of 20 to 21 minutes in length—over twice as long as what the facility manager expected.

Second, the facility manager was accustomed to dealing with his own in-house product, which was simple television cartoon work that only needed 4 to 8 sound effect tracks for each reel. For him this was a single-pass transfer. Our postproduction supervisor had not made it clear that the sound-editorial team was preparing the work in a theatrical design, utilizing all 22 channels for every reel to be transferred.

Because the facility only had a Pro Tools unit that could only play back eight dedicated channels at once, the transfer person transferred channels 1 through 8 all the way through 20 to 22 minutes of an AB reel, not 8 to 10 minutes of a traditional cut reel. Then he rewound back to heads, reassigned the eight playback outputs to channels 9 through 16, transferred that 20 to 22 minute pass, then rewound back to heads and reassigned the eight playback outputs to channels 17 through 22 to finish the reel. Instead of taking an average of half an hour per reel, each reel took an average of 2 hours. Add to that a 2 hour delay because they could not figure out why the timecode from the 24-track was not driving the Pro Tools session.

The crew finally discovered that the reason the timecode was not getting through to the computer was that the facility transfer technician had put the patch cord into the wrong assignment in the patch bay and had not thought to double-check the signal path. To add more woes to the hemorrhaging problem, the facility was running its Pro Tools sessions on an old Macintosh Quadra 800. It was accustomed to a handful of sound effects channels with sprinklings of little cartoon effects that it could easily handle. On the other hand, we ran extremely complex theatrical-designed sound with gigantic sound files, many in excess of 50 megabytes apiece. One background pass alone managed 8 gigabytes of audio files in a single session, a session twice as long as traditional cut reels. At the time, I used a Macintosh PowerMac 9600 at my workstation, and they tried to get by with only a Quadra 800. The session froze up on the transfer person, and he didn't know what was wrong. The editor upstairs kept saying the drive was too fragmented, and so they wasted hours re-defragmenting a drive that had just been defragmented the previous day.

I received an urgent call and drove over to help get things rolling again. I asked them if they had tried opening the computer's system folder and throwing out the Digidesign set-up document, on the suspicion that it had become corrupted and needed to be rebuilt. They didn't even know what I was talking about. Once I opened the system folder and showed them the set-up document, I threw it in the trash and rebooted the computer, then reset the hardware commands. The Pro Tools session came up and proceeded to work again.

Part of the reason why the facility offered such an apparently great transfer deal was that it did not have to pay a transfer technician very high wages, as he was barely an apprentice, just learning the business. He transferred sound by a monkey-see, monkey-do approach; he had been shown to put this cord here, push this button, turn this knob, and it should work. The apprentice was shoved into a job way beyond his skill level and was not instructed in the art of precise digital-to-analog transfer; nor had he been taught how to follow a signal path, how to detect distortion, how to properly monitor playback, how to tone up stock (and why), or how to problem solve.

The facility did not have an engineer on staff, someone who could have intervened with expert assistance to ferret out the problem and get the transfer bay running again. Instead, a sound editor was called down from the cutting rooms upstairs, someone who had barely gotten his own feet wet with Pro Tools, someone only a few steps ahead of the transfer person. Not only was the layback session of Thursday blown completely out, but a second session was necessary for the following day, which ended up taking 9 hours more. As a consequence, I was without my drive and unable to do any further cutting for nearly 2 days because of this collateral oversight. In addition to nearly a thousand dollars of lost editorial talent, the layback schedule that on paper looked like it would take 2 simple hours actually took 14, wiping out the entire allocated monies for all the laybacks—and we had just started the process!

These collateral pitfalls cause many horror stories in the world of filmmaking. Filmmakers’ ignorance of the process is compounded by the failure to ask questions or to admit lack of knowledge; the most common mistake is accepting the lowest bid because the client erroneously thinks money will be saved. Much of the ignorance factor is due not only to the ever-widening gap of technical understanding by the producers and unit production managers, but by the very person producers hire to look after this phase of production—the postproduction supervisor. The old studio system used to train producers and directors, through a working infrastructure where form and function had a tight, continuous flow, and the production unit had a clearer understanding of how film was made, articulating its vision and design accordingly. Today many producers and directors enter the arena cowboy-style, shooting from the hip, flashing sexy terms and glitzy fads during their pitch sessions to launch the deal—yet they so seldom understand that which their tongue brandishes like a rapier.

Many executive-level decision makers in the studios today rose from the ranks of number-crunching accountants, attorneys, and talent agent “packagers,” with little or no background in the art of storytelling and technical filmmaking, without having spent any time working in a craft that would teach production disciplines. They continue to compress schedules and to structure inadequate budgets.

A point of diminishing returns arrives where the studios (producers) shoot themselves in the foot, both creatively and financially, because they don't understand the process or properly consult supervisors and contractors of the technical crafts who can structure a plan to ensure the project's fruition.

PENNY-WISE AND POUND-FOOLISH

A frequent blunder is not adopting a procedural protocol to make protection back-ups of original recorded dailies or masters before shipping from one site to another. The extra dollars added to the line-item budget are minuscule indeed compared to the ramifications of no back-up protections and the consequent loss of one or more tapes along the way.

I had a robust discussion with a producer over the practice of striking a back-up set of production DATs each day before shipping the dailies overseas to Los Angeles. For a mere $250, all the daily DATs would have been copied just prior to shipment. He argued with me that it was an unnecessary redundancy and that he would not line anybody's pockets. Sure enough, 2 months later, the postproduction supervisor of the studio called me up. “Dave, we've got a problem.”

The overseas courier had lost the previous day's shipment. The film negative had made it, but not the corresponding DAT. They had filmed a sequence at night on the docks of Hong Kong. An additional complication arose in that the scene was not even scripted, but had been made up on the spur of the moment and shot impromptu. There were no script notes and only the barest of directions and intentions from the script supervisor.

Consultation with the director and actors shed little light on the dialog and dramatic intent. After due consideration and discussion with the postproduction supervisor, we set upon an expensive and complex procedure, necessary because the producer had not spent that paltry $250 for a back-up DAT copy before lab shipments.

Two lip readers were hired to try to determine what the actors were saying. The television monitors were too small for the lip readers to see anything adequately because the footage was shot at night with moody lighting. This meant we had to use an ADR room where the film image projected much larger. Naturally, the work could not be done in real time. It took the lip readers two full days of work to glean as much as they could. Remember, these were raw dailies, not finished and polished cut scenes. The lip readers had to figure out each take of every angle because the sequence was unscripted and the dialog would vary from take to take.

Then we brought in the actors to ADR their lines as best as they could to each and every daily take. After all, the picture editor could only cut the sequence once he had the dialog in the mouths of the actors.

After the preliminary ADR session, my dialog editor cut the roughed dialog in sync to the daily footage as best as she could. This session was then sent out to have the cut ADR transferred onto a Beta SP videotape that the picture assistant could then digitize into the Avid (a nonlinear picture-editing system). It should go without saying that once the picture editor finished cutting the sequence, the entire dock sequence had to be reperformed by the actors on the ADR stage for a final and more polished performance.

All in all, the costs of this disaster ran upward of $40,000, if you include all collateral costs that would not have been expended if a duplicate DAT back-up had been made in the first place. To make matters worse, they had not secured a completion bond nor had they opted for the errors-and-omissions clause in the insurance policy.

DEVELOPING GRASS-ROOTS COMMON SENSE

Budget properly, but not exorbitantly, for sound. Make sure that you are current on the costs and techniques of creating what you need. Most importantly, even if you do not want to reveal the amount of money budgeted for certain line items, at least go over the line items you have in the budget with the department heads and vendors with whom you intend to work. I have yet to go over a budget that was not missing one or more items, items the producer had either not considered or did not realize had to be included in the process: everything from giving the electrical department enough allowance for extra cable to control generator noise, to providing wardrobe with funds for the soft booties actors wear for all but full-length shots, to allowing enough time for a proper Foley job and enough lead time for the supervising sound editor and/or sound designer to create and record the special sound effects unique to the visuals of the film.

The technicians, equipment, and processes change so fast and are still evolving and changing so quickly that you must take constant pulse checks to see how the industry's technical protocol is shooting and delivering film; otherwise, you will find yourself budgeting and scheduling unrealistically for the new generation of postproduction processes. Since 1989 the most revolutionary aspects of production have been in the mechanics of how technicians record, edit, and mix the final soundtrack—namely, digital technology. This has changed the sound process more profoundly than nearly any other innovation in the past 50 years. Today we are working with G-5s and terabyte drives with speeds that we could only dream about a decade ago.

Costs have come down in some areas and have risen dramatically in others. Budget what is necessary for your film and allow enough time to properly finish the sound processes of the picture. A sad but true axiom in this business is: there is never enough time or money to do it right, but they always seem to find more time and money to do it over!

Half the time, I don't feel like a sound craftsperson. I feel like the guy in that old Midas muffler commercial who shrugs at the camera and says, “You can pay me now—or pay me later.” The truly sad thing is that it is not really very funny. My colleagues and I often shake our heads in disbelief at the millions of dollars of waste and inefficient use of budget funds. We see clients and executives caught up in repeating clichés or buzzwords, the latest hip phrase or technical nickname. They want to be on the cutting edge, they want to have the new hot-rod technologies in their pictures, but they rarely understand what they are saying. It becomes the slickest recital of technical double-talk, not because they truly understand the neat new words but because they think it will make their picture better.

While working on a low-budget action robot picture, I entered the re-recording mix stage to commence predubbing sound effects when the director called out to me, “Hey, Dave, you did prepare the sound effects in THX, didn't you?” I smiled and started to laugh at his jest, when the re-recording mixer caught my eye. He was earnestly trying to get my attention not to react. It was then that I realized the director was not jesting—he was serious! I stood stunned. I could not believe he would have made such a statement in front of everybody. Rather than expose his ignorance to his producer and staff, I simply let it slide off as an offhanded affirmation. “THX—absolutely.”

An old and tired cliché still holds very true today: the classic triangle of structuring production quality, schedule issues, and budget concerns—The Great Triangle Formula: (1) You can have good quality. (2) You can have it fast. (3) You can have it cheap.

You may only pick two of the three. When potential clients tell me they want all three options, then I know what kind of person I am dealing with, so I recommend another sound-editorial firm. No genuine collaboration can happen with people who expect and demand all three.

One False Move is a classic example of this cliché in action. When Carl Franklin and Jesse Beaton interviewed me, we came to an impasse in the budget restrictions. I rose, shook their hands, bid them well, and left. Carl followed me down the hall and blocked my exit. “I'm really disappointed with you, Yewdall!”

“You're disappointed with ME?” I sighed. “You're the ones with no money.”

“Yeah, well, I thought one Cormanite would help out another Cormanite,” snapped Carl.

I grinned. “You worked with Roger Corman? Why didn't you say that to begin with? Cormanites can always work things out.”

And with that, we returned to the office and told their postproduction supervisor to just sit quietly, listen, and learn something. First, I asked what the release date was. There was no release date. Then why the schedule that Graham had outlined? Because he had just copied it from another movie and did not know any better. All right, if you don't have much money then you must give me a lot more time. If I have to hire a full crew to make a shorter schedule work then that is “hard” dollars that I am going to have to pay out. On the other hand, if I have more time, then I can more of the work personally, making do with a smaller crew, which in turn, saves the outlay of money that I would otherwise have to make.

Carl and Jesse were able to give me six extra weeks. This allowed me to do more work personally, which was also far more gratifying on a personal level. That the picture was ready for the re-recording process during a slow time in the traditional industry schedule also helped.

Here is another point to note: In peak season, financial concessions are rare. If you hope to cut special rates or deals, aim for the dead period during the Cannes Film Festival in May.

THE TEMP DUB

A new cut version of a picture is seen as counterproductive by studio executives, as they are usually not trained to view cut picture with only the raw cut production sound. They don't fully understand the clipped words and the shifts in background presences behind the various angles of actors delivering their lines. They watch a fight scene and have difficulty understanding how well it is working without the sounds of face impacts and body punches. This has caused an epidemic of temp dubbing on a scale never before seen or imagined in the industry.

Back in the early 1980s, we called temp dubs the process of flushing $50,000 down a toilet for nothing. Today, we accept it as a necessary evil. Entire procedures and tactical battle plans are developed to survive the inevitable temp dub, and they do not come as a single event. Where there is one, there will be more. How many times has a producer assured me not to worry about a temp dub? Either there will not be one because no money is in the budget for one, the producer insists, or there will be one temp dub and that is it!

A comedy spoof, Transylvania 6-5000, which I supervised the sound for, is an excellent example of what can go horribly wrong with temp dubs when there is no defined structure of productorial control. Two gentlemen, with whom I had had a very fine experience on an aviation action film the previous year, were its producers. I was assured there would be no temp dub(s), as there was certainly no money in the budget for one. But the project had a first-time director, a respected comedy writer on major films who was trying to cross over and sit in the director's chair. Being a talented writer, however, did not suddenly infuse him with the knowledge, wisdom, or technical discipline about how motion pictures were made, especially about the postproduction processes.

We had no sooner looked at the director's cut of the picture when the director ordered up a temp dub. I decided not to cut my wrists just then, as I picked up the phone and called the producer for an explanation. He was as surprised as I was and told me to forget about it. I instructed my crew to continue preparing for the final. Within an hour, I received a call from the producer, apologizing and explaining that he could do nothing about it. If the director wanted a temp dub, then we needed to prepare one. I reminded the producer that no allowance had been made for the temp dub in the budget. He knew that. He had to figure things out, but for now, he said, just use budget monies to prepare the temp dub. He would figure out how to cover the overage costs. I asked the producer why he could not block the director's request. After all, I had been trained that the pecking order of command gave producers the veto power to overrule directors, especially when issues of budget hemorrhaging were the topic of conversation. The producer explained that the hierarchy was not typical on this picture; the director was granted a separate deal with the studio that effectively transcended the producer's authority over him. I reluctantly agreed to the temp dub, but reminded the producer that it would seriously eat into the dollars budgeted for the final cutting costs until he could fortify the overage.

After the first temp dub we had resumed preparations for the final when we received a second phone call from the producer. The director had ordered up a second temp dub for another series of screenings. No compensation had been made for the first temp, and now a second temp dub was being ordered? The producer sighed and told us to just continue to use budget dollars until he could figure it out. This would definitely be the last temp dub, and the nightmare would be over.

The nightmare continued for four weeks. Each week the director ordered up yet another temp dub. Each week the producer was unable to deal with studio executives and was dismissed from acquiring additional budget dollars to offset the temp dub costs.

After the fourth temp dub, the producer asked how much longer it would take us to prepare the final mix. I shrugged and said that as far as I was concerned we were already prepared. His eyes widened in disbelief as he asked how that was possible. I told him that the four temp dubs had burned up the entire sound-editorial budget due to the director's dictates. Nothing was left to pay the editors to prepare the final soundtrack unless compensation was forthcoming; therefore, the fourth temp dub would have to serve as the final mix. The producer did not believe we would really do that. To this day, the film is shown on television and viewed on DVDs with the fourth temp dub as its ultimate soundtrack.

You can easily see how a judgment error in the director/producer jurisdiction can have calamitous collateral effects on the end product. Someone, either at the studio or over at the attorney's offices, had been allowed to structure a serious anomaly into the traditional chain-of-command hierarchy. This unwise decision, made long before the cameras ever rolled, laid the groundwork for financial and quality control disasters.

The truth of the matter, this has not been a unique tragedy. I could name several major motion pictures whose supervising sound editors told me that they were so balled up by producing temp dubs nearly every week that they never had a chance to properly design and construct a real soundtrack and that those films are really just temp dubs.

Remember this one truth. No one gives you anything free. Someone pays for it; most of the time—you. If producers only knew what really goes on behind the scenes to offset the fast-talking promises given a client to secure the deal, they would be quicker to negotiate fairly structured relationships and play the game right.

READ THE FINE PRINT

Several years ago a friend brought me a contract from another sound-editorial firm. He told me the director and producer were still fighting with the editorial firm regarding the overages on their last picture. This contract was for a major motion picture, and they did not want to end up suffering a big overage bill after the final sound mix was completed. Would I read through the contract and highlight potential land mines that could blow up as extra “hidden” costs? I read through the contract.

The editorial firm guaranteed, for a flat fee, a Foley track for each reel of the picture. The cost seemed suspiciously low. When I reread it, I discovered it would bill a flat guaranteed price of “a Foley track,” in other words, Foley-1 of each reel. Foley tracks 2 through (heaven knows how many) 30 to 40 would obviously be billed out as extra costs above and beyond the bounds of the contract.

Figure 4.3 The deal makers.

All the Dolby A noise-reduction channels would be thrown into the deal free. Sounds good—except and that by this time nobody of consequence used Dolby A channels, and those who did had already amortized their cost and threw them free into every deal anyway. Of course, nowhere in the contract did it specify about the free use of Dolby SR channels, the accepted and required noise-reduction system at the time. This would, of course, appear as extra costs above and beyond the bounds of the contract.

To help cut costs, the contract specified that all 35-mm fullcoat rolls (with the exception of final mix rolls) would be rental stock, costing a flat $5 each. It was estimated, based on the director's last project and the style of sound postproduction tactics that this project would use at least 750,000 feet of 35-mm fullcoat. That would cost the budget an estimated $3,750 in stock rental.

Since the picture and client were of major importance, the sound-editorial firm wrote into the contract it would purchase all brand-new stock and guarantee to the client that the first use of this new rental stock would be on this picture. This must have sounded delicious to the producer and director. However, in a different part of the contract, near the back, appeared a disclaimer that if any fullcoat rental stock was physically cut for any reason, it would revert from rental to purchase, the purchase price in keeping with the going rates of the studio at the time. A purchase price was not specified or quoted anywhere in the contract. I happened to know that the current purchase price of one roll of fullcoat at the studios averaged $75. This would end up costing the producer over $56,000! No risk existed for the sound-editorial firm; the director was notorious for his changes and updates, so the expectation that each roll of fullcoat used would have at least one cut in it, and would therefore revert to purchase price, translated into money in the bank.

My advice to the producer was to purchase the desired-grade quality fullcoat directly from the stock manufacturer at $27 per roll. Since the production would use so much fullcoat, I suggested the producer strike a bulk-rate discount, which brought the price down to $20 per roll. This would give the producer a guaranteed line-item cost of $15,000, along with the peace of mind that any changes and updates could be made without collateral overages leaching from the budget's fine print regarding invasive use.

I then came across a paragraph describing library effects use. The contract stated that the first 250 sound effects of each reel would be free. A fee of $5 per effect would be added thereafter. First, most sound-editorial firms do not charge per effect. The use of the sound library as required is usually part of the sound-editorial contract. In the second place, no finite definition of what constituted a sound effect was given. If the same sound effect was used more than once in a reel, did that sound effect constitute one use, or was every performance of that same sound effect being counted separately each time? If the editor cut a sound effect into several parts, would each segment constitute a sound effect use? The contract did not stipulate. I might add that this picture went on to win an Academy Award for Best Sound—but industry rumors placed the overages of the sound budget well over $1 million.

BUT YOU SAID IT WOULD BE CHEAPER!

While I was working on Chain Reaction, a studio executive asked to have lunch, as he wanted to unload some frustrations and pick my brain about the rapid changes in postproduction. For obvious reasons, he will remain anonymous, but he agonized over his Caesar salad about how he just didn't understand what had happened. “You guys said digital would be cheaper!”

“Wait a minute,” I stopped him. “I never said that to you.”

“I don't mean you. But everybody said it would cost less money, and we could work faster!”

“Name me one sound editor that told you that. You can't, because it wasn't one of us who sold you this program. It was the hardware pushers who sold it to you. You deluded yourselves that it would cost less and allow you to compress schedules. Now what have you got? Compressed schedules with skyrocketing budgets.”

“So let's go back to film!”

I smiled. “No. Do I like working in nonlinear? Yes. Do I think that it is better? Not necessarily. Do I want to go back to using magnetic film again? No.”

“Where'd we go wrong?” he asked.

“You expected to compare apples with apples—like with like. That's not how nonlinear works. With the computer and the almost weekly upgrades of software, we can do more and more tasks. Because we can do more, the director expects us to do more. You cannot expect us to have access to a creative tool and not use it.

“Are we working faster than before? Mach four times faster. Can we ignore using the extra bells-and-whistles and use the equipment as if it were an electronic Moviola? Absolutely NOT! The sooner you stop throwing darts at the calendar as you make up these artificial schedules and listen to your craftspeople's advice, the sooner you are going to start injecting sensibility into your out-of-control postproduction budgets and start recapturing an art form that is quickly ebbing away. Otherwise, you had better take a deep breath and accept the fact that the reality of today's postproduction costs are out of control, fueled by directors who find themselves in a studio playpen with amazing creative toys at their disposal. They are going to play with them!”

BUDGET FUNDAMENTALS

One of the most frequent agonies in the birthing process of a film is the realization that the budget for the sound-editorial and/or re-recording process was inadequately structured and allocated. Since these two processes are ranked among the most misunderstood phases, they are the two that often suffer the most.

The process is not alleviated by those who strive to help the new independent producers or unit production managers (UPMs) by trying to develop “plug-in” budget forms, whether printed or via computer software developed by those knowing even less about the postproduction process. More often than not, these forms are copied from budgets acquired from someone working on another show or even from someone trained during a different era. Not understanding the process, the software writer or print-shop entrepreneur copies only what is seen, thereby carrying only those line items and detail (especially the lack thereof) of whatever is on the acquired budget breakdown, including all the mistakes.

We often have been shocked to find that the producers or UPMs did not allow certain critical line items into their own budgets because they did not see an allowance for a line item in their budget form. Not understanding the sound-editorial and mixing process themselves, they did not add their own line items as needed. The ignorance and ensuing budget disaster is carried from project to project, like bad genes in a DNA strain, photocopying the blueprints for disappointment and failure onto the next unsuspecting project.

Understanding the Budget Line Items

Following are some important budget line items to consider. Remember, these costs directly impact the soundtrack. These line items do not include creative noise abatement allowances. One must use common sense and draw upon experienced craftspeople to assist in planning a successful soundtrack.

Production Dialog Mixers vs. Custom Sound Effect Mixers

In addition to the time allocated for the production sound mixer, the smart producer budgets time for the mixer to go on a location field trip in order to see and hear the natural ambience, walk the practical location and hear the potential for echo, note nearby factories and highways, and detect the presence of aircraft flight paths. In addition, the mixer takes a quick overview of where power generators might be parked, and if natural blinds exist to help block noise or if acoustic gear should be brought to knock down potential problems.

With regard to a pristine dialog track, the boom operator is the key position. The production mixer is the head of the production sound crew, but even the mixer will tell you the boom operator is more important. If the microphone is not in the right position, what good is the subsequent recording? More often than not, the producer or UPM always underbudgets the boom-operator slot. I have seen production mixers shave some of their own weekly rates so that those extra dollars can bolster the boom operator's salary.

Most smaller pictures cannot afford the cable man (the term “cable man” has stuck, regardless of the technician's gender). The cable man also handles the second microphone boom as well as other assistant chores. On one picture the producer had not allowed the hiring of a cable man, alleging that the budget could not support one. One night, the crew was shooting a rain sequence at a train station. The production mixer was experiencing many pops on the microphone because the rain was heavier than first anticipated. Needing the rain bonnet, he asked the director for five minutes so that the boom operator could fetch one from the sound truck. The director said no, “We'll just loop his lines later in postproduction.” The following night, the actor was tragically killed in a stunt crash during filming. What do you think it cost to fix the rain-pelted production track, as opposed to the cost of the requested 5-minute wait the night before?

On large productions, especially those with a great deal of specialized equipment, vehicles, or props that may be expensive or impossible to acquire later, increasingly more producers factor a production FX recordist into the budget. Usually these individuals have a reputation for knowing how to record for sound effect use and for effectively interfacing with the postproduction crew to ensure needed recordings. They often work separately from first unit, usually arranging to work with vehicles or props not being used at the time, taking them out and away to areas conducive to quality recordings.

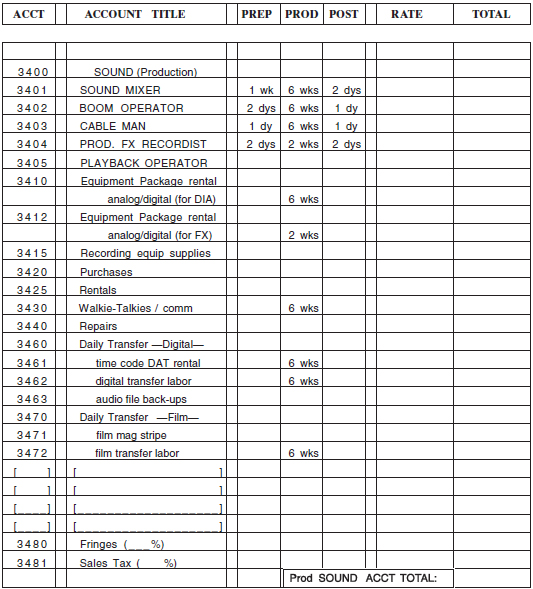

Figure 4.4 Production sound budget.

For instance, a Trans-Am may be the hero vehicle for the picture. The director may want the Trans-Am recorded to match the production dialog, but recorded as a stunt-driven vehicle to give the “big sound” for postproduction sound editorial. Recordings of this type are usually done off-hours, not while the shooting unit is in need of any of the special props or locations in question. Those occasions do arise, though, when the production FX recordist will record during actual shooting, such as recording cattle stampeding through a location set. It may be a financial hardship to field the cattle and wranglers after the actual shoot just to record cattle stampeding. Recordings like these are best orchestrated in a collaborative manner with camera and crew.

Each situation requires a different problem-solving approach. Common sense will guide you to the most fruitful decision. However, production effects recording during principal photography demands attentive regard for suppressing inappropriate noises often made by the production crew. Such events are incredibly challenging and seldom satisfying from the sound mixer's point of view.

The project may require that precise wild track recordings be made of an oil rig, say, or a drawbridge spanning a river. These types of sound recordings should be entrusted to a recordist who understands the different techniques of recording sound effects rather than production dialog (major differences explained later in this book). The production FX recordist is not usually on for the entire shoot of the picture, but brought on as needed, or for a brief period of time to cover the necessary recordings.

A perfect example was a major action thriller with a huge car chase scene through Paris. The sound supervisor showed me 50 minutes of the work-in-progress footage, as he wanted me to come on the picture to work with him in handling the vehicle chase scenes. It looked very exciting, a sound editor's dream! The first thing I asked was how were we going to handle custom recording these various cars? We knew that at least two of them were not even available in the United States yet. He asked for a recommendation and proposal. The next day I presented him with my plan: hire Eric Potter, who specializes in custom sound effect recording and let him recommend the sound equipment package that he feels he would need, including any assistant help that we knew he would require. Send them over to Paris where they were still filming the picture, and, as a bonus while they were there, have them record a ton of stereophonic ambiences.

A couple of days later, the sound supervisor came into the office and told me that the producer had decided against my plan. Why spend the money when he would just have the production mixer custom record the vehicles on his off time? I threw up my hands. I knew this man, a son of an ex-studio executive, a second-generation film producer. I had worked for him on another picture several years before. I knew well the fact that he did not understand and appreciate the collateral costs that he was about to waste by not following the custom-recording plan.

I thanked the supervisor for considering me to work on the film, but I knew what “postproduction hell” was coming down the pike. Another studio had recently offered to build a sound-editorial suite to my custom design to entice me over to them. I apologized to my friend and politely turned down doing the car picture to take the deal to move to the other studio.

Several months later that sound supervisor called me up and asked if he could come over and check out my new room. Sure I said, though I thought it strange because he must be knee deep in a difficult project and how could he afford to waste a valuable weekday afternoon with me? He sat down and told me the temp dub was a disaster. Everything I said would go wrong had gone wrong, and then some. What was the name of that recordist I had recommended? I replied that to custom record the cars now would cost a great deal more than if they had done it during the shoot, and sure enough, after shipping the cars over to California, renting an air field, trying to find cobblestone streets where they could record, etc., the sound supervisor told me the production unit spent nearly 10 times the amount of money that my original plan would have cost.

This is not a lesson about ego; this is a lesson about understanding that production dialog mixers are trained to record dialog. There is an exact discipline, technique, and approach that they are trained to utilize to capture the best production dialog track they can. It is seldom the technique that we utilize when we record sound effects. The two styles are completely different. That is why you need to hire a specialist such as Eric Potter, Charles Maynes, or John Fasal to custom record the sound effect requirements of your project.

The Production Sound Budget

Production recording mixers can and prefer to use their own equipment. This is of great benefit to the producer for two reasons. First, the production mixer is familiar with his or her own gear and probably yields a better-quality sound recording. Second, in a negotiation pinch, the production mixer is more likely to cut the producer a better equipment-package rental rate than an equipment rental house. Remember too that the production mixer is usually responsible for and provides the radio walkie-talkies and/or Comtech gear for crew communications. Communication gear is not part of the recording equipment basic package but handled as a separate line item.

As you consider the kind of picture you are making, the style and preference of the production recording mixer, and the budget restraints you are under, you will decide whether to record analog or digital (single-channel, two-channel, or multichannel). This decision outlines a daily procedure protocol from the microphone to picture editorial—how to accomplish it and what you must budget.

With very few exceptions, virtually all dailies today are delivered to picture editorial digitally. There are three ways of doing this. The first two choices involve having the production mixers make daily sound tapes or removable hard drive recording storage, either digitized (if by DAT) or transferred as audio files that already exist on a removable hard drive so that they can be synced up to visual image at picture editorial.

1. You may choose to have the laboratory do the transfer. This in-lab service may be more convenient for you, as they deliver you a video telecine transfer with your sound already synced up to the picture. Sounds good? The downside is that it is a factory-style operation on the laboratory's part. Very few lab services have master craftspeople sound techs who think beyond the timecode numbers and sound report's circled takes. The precision and attention to detail are often lost with the necessary factory-type get-it-out schedule.

More importantly, you introduce, at the very least, a generation loss by virtue of the videotape and, at worst, a lot of new noise and hums depending on the quality of the telecine. I do not care what the laboratory tells you—all video transfers introduce degradation and system noise to some degree. I have also personally inherited numerous projects that producers had had the laboratories handle sound transfer in this manner and I have been underwhelmed with their level of service and expertise.

One of the underlying reasons for this is that in order to compete, the laboratories have to keep their labor costs down. Bean counters only know numbers on a page: so many technicians, working at a certain pay rate, equals a profit or loss on a foot of film processed. What is happening is that the real craftspeople who really know why they do things the way they do them, who have seen all of the freakish problems in production and have their own veteran memories so they can instantly access and problem solve the issue, are let go when their pay rate reaches a certain level. On paper, a lower paid technician makes business sense. The problem is that it usually takes three to six “newbys” to handle and turn out the work that one veteran knows how to do. This is a collateral invisible chuckhole that the studio accountants just do not understand. More mistakes are made because less experienced beginners are still learning; more and more work has to be redone because it was improperly done the first time.

2. You may choose to have your own assistant picture editor transfer (digitize) the sound straight into your nonlinear editing system (such as Final Cut Pro or Avid), then sync the digitized audio files to the digitized picture. This certainly bypasses the laboratory factory-style issues—but more importantly, it places the burden of quality control and the personal project precision on the picture-editorial team. This technique is mandatory if you hope to utilize the OMF procedure later in postsound editorial, as I have come to never trust any material that was handled by a film laboratory, whether telecine transfer or even digitized audio files, if I ever hoped to use OMF in the postsound edit equation. (OMF, open media framework, is covered in greater detail in Chapter 14.)

3. Your third choice is to have your production sound mixer do it, so to speak. By this I mean that the sound mixer would be recording sound to either the DEVA IV or V or to the Nagra V or several other very high-quality recorders, such as the Sound Devices 744t, the Aaton Cantar X, the Fostex PD6, or such other highly respected recording units. All these units are FAT 32 formatted to record four to eight discreet channels of audio signal, all capable of up to at least 96-kHz/24-bit recording (a few are rated to record as high as 192-kHz/24-bit) in industry standard audio formats BWF (Broadcast Wave Format) and some also record in .WAV audio format files. (Near the end of Chapter 5, we take a brief look at several of these units. Chapter 23, which is devoted to an in depth discussion of the Nagra V, is available from www.elsevier.com as a downloadable file.)

Timecode and other scene/take reference data are included in the directory information of these files, making them instant “drag-and-drop” transfer items into nonlinear picture and audio workstations. As you will read in more detail later, your sound mixer will simply change out the removable hard drive (or flash memory unit) and replace it, or he or she might simply make a back-up clone out of their recording setup and burn a DVD-R to ship straight to picture editorial, ready to simply be data-transferred into the computer.

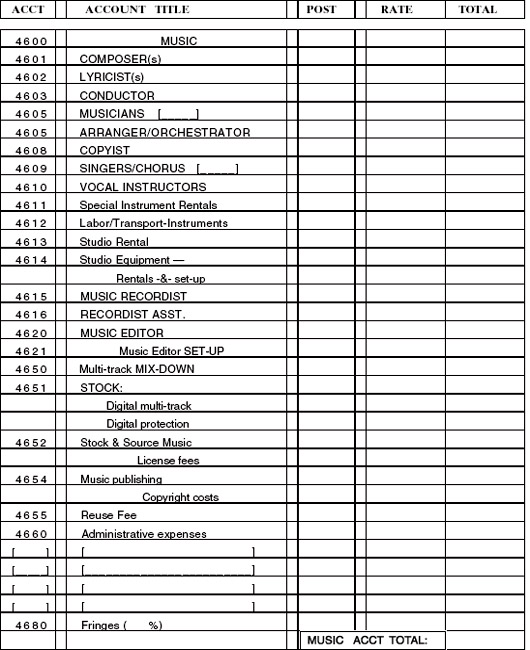

Figure 4.5 Music budget.

Music Budget

Once the producer settles on the music composer and they thoroughly discuss the conceptual scope of work to be done, the composer outlines a budget to encompass the financial requirements necessary. I am not even going to pretend to be an authority about the budget requirements for music, just as I would not want a music composer to attempt to speak for sound-editorial budget requirements; therefore, you should consult your music director and/or composer for their budgetary needs.

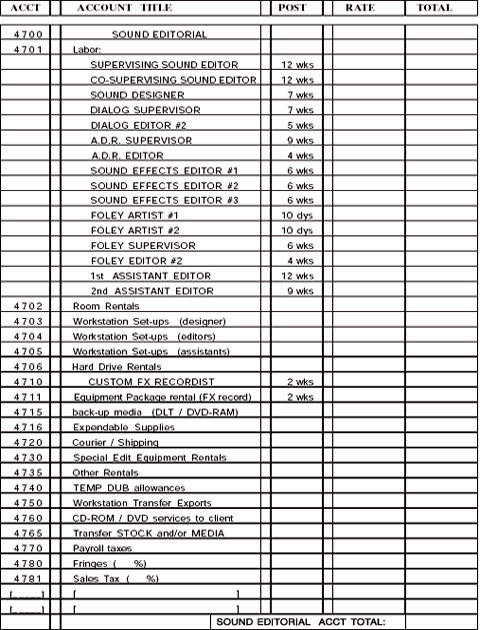

Sound-Editorial Budget

The “Labor” line items of the sound-editorial detail illustrated in Figure 4.6 are geared toward a medium-sized feature film with a heavy action content. (I discuss the individual job slots and their contribution to the soundtrack later in this book.)

“Room Rentals” refers to the actual rooms where editorial workstations with monitors and computers are set up and used by the editorial editors and assistants as necessary for the editorial team. This cost does not reflect the equipment, but many sound-editorial firms do include at least a 200 to 300 gigabyte external drive in the use of the room. Obviously, with today's digital memory requirements for digitized picture, thousands of audio files and edit sessions will only get you started.

Each sound editor has a workstation system requirement. A sound designer has much more gear than a dialog editor. Assistant sound editors have different kinds of equipment requirements than do sound editors. The workstation system rentals obviously vary from one requirement to another.

Sound editors need more hard drives than the 200 to 300 gigabyte drive that their room rental may allow. This need is dictated by how busy and demanding the sound-editorial requirements are; again, every show is different. I have an “informal” Pro Tools set-up under the end table of my couch so that I can put my feet up on the coffee table while I spend time with my wife in the evenings, and I have 1.5 terabytes of sound library drives under the end table with two firewire cables that poke up when

I want to plug in my laptop and go to work. My formal workstation room is set up entirely differently of course, where I can properly monitor in 5.1 and do serious signal analysis and mixing. It all depends on what kind of work you are doing and what setup is structured for what purpose.

The “Custom FX Recordist” may, at first glance, look like a redundancy slot from the sound (production) budget page. It is not! The production FX recordist covered the production dialog and any sound effects that were captured during the actual filming of a scene. From time to time, good production mixers know how to take advantage of recording production vehicles, location background ambiences, and props unique to the filming process. Later, usually weeks and even months later, the sound-editorial team is up against a whole new set of needs and requirements. It may need to capture specialized backgrounds not part of the original location, but needed to blend and create the desired ambience.

Figure 4.6 Sound-editorial budget.

A good example of this is when I supervised the sound for the 1984 version of The Aviator (starring Christopher Reeve). The director and producers were biplane enthusiasts and wanted exact and authentic recordings for the final film; however, they were prohibited from using the authentic Pratt-Whitney engines of 1927 because the insurance company felt that they were not strong enough, especially as Christopher Reeve did all of his own flying (being an avid biplane pilot enthusiast himself). Therefore, none of the production recordings of the aircraft that were made during the production shoot could be used in the final film. Every single airplane engine had to be custom recorded in postproduction to match how the engines should have historically sounded for 1927.

In Black Moon Rising, the stunt vehicle looked great on film, portrayed as a huge and powerful hydrogen jet car, but in actuality it only had a little four-cylinder gasoline engine that, from a sound point of view, was completely unsuitable. As the supervising sound editor, I had to calculate a sound design to “create” the hydrogen jet car. You will want your custom sound effect recordist to record jets taking off, flying by, landing, and taxiing at a military air base. He or she may need to have the recordist go to a local machine shop and record various power tools and metal movements. These recordings, as you can see, are completely different and stylized from the production dialog recordist, who was busy recording a controlled audio series of the real props or vehicles as they really sounded on the set.

Referring to the “back-up media” line item, back-ups can never be stressed enough. Every few days, sound editors turn their hard drives over to the assistant sound editors, who make clone drive back-up copies, depending on the amount of material, possibly making DVD-R back-ups of “Save As” sessions. Many of the larger sound-editorial firms have sophisticated servers, supplying massive amounts of drive access and redundancy. You can never be too careful about backing up your work.

To this day I can take a Pro Tools session document from any one of the sessions from Starship Troopers (as well as other films) and boot up the session. The software will scan the drives, find the corresponding archived material, and rebuild the fades in a few minutes. I have resurrected FX-D predub from reel 7, the invasion sequence of the planet Klendathu (one of scads of predub passes that seemed endless). Without good and disciplined habits in file identification protocols, disk management procedures, and back-up habits, resurrecting a session like this would be extremely difficult, if not impossible.

“TEMP DUB allowances” is a highly volatile and controversial line item. The fact is, directors have become fanatical about having temp dubs because they know their work is being received on a first-impression style viewing, and anything less than a final mix is painful. Studio executives want test screenings for audiences so they can get a pulse on how their film is doing—what changes to make, where to cut, and where to linger—all of which necessitate showing it with as polished a soundtrack as possible.

Extra costs may be needed to cover the preparation of the temp dubs separate from the sound preparation for final mix predubbing. Producers and supervising sound editors may want a separate editorial team to handle most of the temp dub preparation, as they do not want the main editorial team distracted and diluted by preparing temp dubs. (Temp dub philosophy is discussed later.)

“Workstation Transfer Exports” refers to the common practice of sound editorial to make “crash downs” (multichannel mixes) of certain segments of action from digital workstations and to export them as single audio files for picture editorial to load into their Final Cut Pro or Avid picture-editing systems and sync up to picture, there by giving picture editorial few work-in-progress sections, such as action scenes, to assist the director and picture editor as work continues. Figure 4.7 illustrates the raw stock supply for the production recording mixer. Note the back-up media.

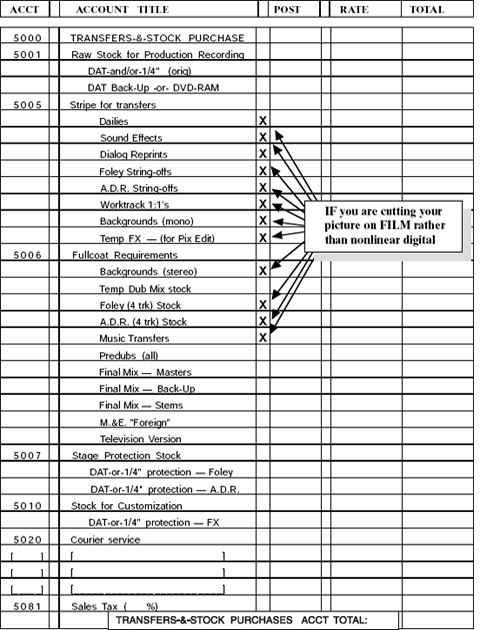

Transfers and Stock Purchase

Unless you are cutting your picture on film, the “Stripe for Transfers” line item hardly affects you. This is where you would budget your 35-mm mag stripe and fullcoat costs if you were still cutting on film.

Very few of today's postproduction facilities are still recording ADR and/or looping sessions to analog 24-track 2” tape—but you may run into one or two of them along the way, so you should understand the format. If you find that you need to use a service that still uses 2” tape, refer to the ADR “String-offs” line item. You need to consider the following: five 24-track rolls cover a 95- to 100-minute motion picture. Unless you have extremely complex and overlapping ADR, you should require only one set of 24-track rolls. You will require a second set of 24-track rolls if you are planning to record Group Walla, especially with today's stereophonic microphone set-ups. We will discuss ADR and looping techniques and the recording format options in Chapter 16.

I cannot imagine any Foley stage still recording Foley to 24-track 2” tape, but if you find that your sound facility is still using this format, you need to refer to the “Foley String-offs” line item, the same considerations apply as before. Some films require more Foley tracks than others, so you would simply allow for a second set of 24-track rolls. Sometimes Foley only requires a few extra channels, and if the Group Walla requirements are not considered too heavy you can set aside the first few channels for the overflow Foley tracks and protect the remaining channels for the Group Walla that has already been done or has yet to be performed.

In both the ADR and Foley stage-recording requirements, I am sure you have noticed that I have not yet mentioned recording straight to an editing workstation hard disk. We will talk more about this in Chapter 16 (for ADR/looping) and Chapter 17 (for Foley). The majority of your postproduction sound services for recording your ADR/looping sessions and/or your Foley sessions will be straight to a hard disk via nonlinear workstations such as Pro Tools. Though this procedure will not require a transfer cost in the traditional sense of “transferring” one medium to another medium, you will need to back up the session folder(s) from the facility's hard drive to whatever medium you require to take to your editorial service. This medium could be your own external 200 to 300 gigabyte hard drive, or you could have the material burned to DVDRs, or some other intermediate transport protocol you have decided to use. If that is the case, you need to budget for it under “Hard Drive Media Back-ups.”

In reference to the “Fullcoat Requirements,” you will probably not require fullcoat for ADR or Foley recording. I have not heard of any ADR or Foley stages using fullcoat now for several years. The 4-channel film recorders have, for the most part, been replaced by 24-track 2” analog tape and direct-to-disk workstation recording systems such as Pro Tools.

Figure 4.7 Transfer budget.

Depending on which studio you opt to handle the re-recording chores of your project, you may still require 35-mm fullcoat for some or all of the predubbing and final mix processes, although most mixing is done digitally today using hard drive systems.

You must allow for protection back-up stock when you have ADR or Foley sessions (see the “Stage Protection Stock” line item). There may be a few ADR stages that still use DAT back-up, even though you are recording to a Pro Tools session. The sound facility where you contract your stage work may include this cost in its bid. You must check this—make sure to take an overview of how many protection DATs are allowed and the cost per item if you decide to use such tape protection.

Some sound facilities charge the client a “head wear” cost for using customer-supplied stock. This is nothing but a penalty for not buying facility's stock, which has obviously been marked up considerably. Find out the kind of stock the facility uses and then purchase the exact brand and type of stock from the supplier. Not only will you save a lot of money but you will pull the rug out from anyone trying to substitute “slightly” used reclaim stock instead of new and fresh. This is a common practice.

Postsound Facility

Referring to the “TEMP DUB(s)” line item (Figure 4.8), note for the purpose of discussion that we have reserved 4 days for temp dubbing in this budget sample. This can be used as 4 single temp mixing days, as 2 two-temp mixing days, or as 1 major 4-day temp mix.

We have a fairly good production track, for this budget example, but we have several segments where we need to loop the main characters to clean out background noise, improve performance, or add additional lines. We budgeted 5 days on the ADR stage. For this project, we have fairly large crowd scenes, and although we expect that sound editorial has all kinds of stereophonic crowds in its sound effects library, we want layers of specialized Crowd Walla to lay on top of the cut crowd effects. We budgeted 1 day to cover the necessary scenes (see the “A.D.R. STAGE & Group Walla” line item).

Note that you need to check your cast budget account and ensure that your budget has a line item for Group Walla. Many budgets do not, and I have encountered more than one producer who has neglected to allow for this cost. In this case, we budgeted for 20 actors and actresses, who all double and triple their voice talents. With four stereo pairs of tracks, a group of 20 voices easily becomes a chanting mob scene or terrified refugees.

Here we budgeted 10 days to perform the Foley (see “FOLEY STAGE”), giving us 1 day per reel. This is not a big budget under the circumstances—action films easily use more time—but we were watching our budget dollars and trying to use them as wisely as possible. In a preliminary meeting with the supervising sound editor, who the producer had already set for the picture, we were assured that 10 days were needed for those audio cues that must be performed on the Foley stage. Other cues that could not have been done on a Foley stage, or that could have been recorded in other ways or acquired through the sound effects library, were not included in the Foley stage scheduling.

Figure 4.8 Post-sound budget.

When it comes to “PREDUBBING,” one should always think in terms that more predubbing means a faster and smoother final mix; less predubbing means a slower and more agonizing final mix with a higher certainty of hot tempers and frustration. (You will read a great deal about mixing styles and techniques as well as dubbing stage etiquette and protocol later in this book.)

This budget allowed 8 days of final (see the “FINALS” line item). The first day is always the hardest. Reel 1 always takes a full day. It is the settling-down process, getting up to speed, finding out that the new head titles are two cards longer than the slug that was in the sound videos, so the soundtrack is 12½ feet out of sync, stuff like that. This always brings the we-will-never-get-there anxiety threshold to a new high, causing the producer to become a clock-watcher. But as reel 3 is reached, one witnesses rhythm and momentum building … 8 days is enough for this picture after all.

When the primary mix is finished, one then interlocks the final stems with the digital projector and screens the picture in a real-time continuity. Dubbing reel by reel, then viewing the film in a single run, are two different experiences. Everybody always has plenty of notes for updates and fixing, so we budgeted 2 days for this process.

Now we want to take the picture out with its brand-new, sparkling soundtrack and see what it does with a test audience. Depending on how we intend to screen the film, we may need to make a screening magnetic film transfer, if we are test screening on 35-mm print. This is best accomplished by running the mix through the mixing console so it can be monitored in the full theatre environment for quality control. We take this screening copy mix and our 35-mm silent answer print and run an interlock test screening somewhere that is equipped for dual interlock (and there are many venues).

It is a good idea to have a test run-through of the interlock screening copy materials before the actual test screening. I have seen too many instances where the client cut the schedules so tight that the last couple of reels of the screening copy was actually being transferred while the first reel was rolling in the test screening—not a good idea. While Escape From New York started to be interlock screened during a film festival on Hollywood Boulevard, we were still finishing the final mix on reel 10 back at the studio!

After the test screening, we have notes for further changes and updates. We need to allot monies to have the dialog, music, and effects stems as well as the predubs transferred into nonlinear editing hard drives for sound editorial to update and prepare for the stage.

To save money and any potential generation loss, we remix the updates stems and predubs (see the “Stem Remixing Updates” line item) straight from Pro Tools systems on the stage and interlocked to the machine room. We budgeted 2 days to remix the updated stems and predubs. We wisely have another test screening. Once we sign off on the both the film and its sound mix, we need to make the “2-track PRINT MASTER.”