Chapter 21

Emerging Technologies

Sound Restoration and Colorization

5.1 TO 6.1 AND HIGHER

What Is 5.1?

Back in mid-1990s, a young sound department trainee burst into my room. He was all excited as he announced that the decision had been made to mix the soundtrack we were working on in “five-point-one”! Wasn't that great?! I smiled at the news. He spun on his heels and disappeared down the hall to tell the rest of his friends.

My smile vanished as I sat there, stumped at the announcement. What the devil was “five-point-one”? This was the new breakthrough sound technology that everybody was talking about around town. Gee, I was going to have to learn a whole new way of doing things. I decided that I did not want to disclose my ignorance too blatantly, so I slipped down the hall and knocked on the door of our resident engineer.

“I hate to admit this, but I don't know what five-point-one is. Could you explain it to me?”

His eyebrows shot up. “Oh, you're going to love it! The sound comes out of the left speaker, the center speaker, the right speaker, as well as split surrounds, and we have a subwoofer.”

I waited for the shoe to drop. “Yeah—what else?”

He shrugged. “Isn't that great?”

I studied his face suspiciously. “That's five-point-one?”

“Yeah.”

I turned and paced back to my room. We've been doing that for the last 30 years! It's called theatrical format! What is so new about this?! Of course what was so important about it was that it was an encode that would allow the home consumer to have true dedicated audio signals assigned to the proper speakers in their home entertainment system to replicate the theatrical presentation with a compression that would allow this enormous amount of audio information to take up less space on a DVD. It would mirror what we have been doing for cinema for the last three decades. Okay, that's a good thing. So let's just remove the idea that it is a new sound system—it is not. It is a new sound delivery format, a better way to bring the big theatrical sound to the consumer.

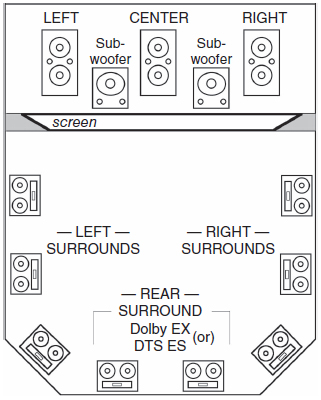

Figure 21.1 The theatrical speaker layout.

So, first we should review is the speaker layout for theatrical presentation.

Center speaker is where all dialog (except for more recent mixing philosophy) emanates.

Subwoofers (also known as “baby booms”) are low-frequency speakers that sit in between the left-and-center and center-and-right speakers. These speakers reproduce very low-frequency audio signals; some of them are subharmonic and are meant to be felt and not just heard.

Left speaker and right speaker is where the stereophonic presentation of sound effects and music live (with occasional hard-left or hard-right placement of dialog).

Left surround speaker and right surround speaker is where a growing taste in aggressive 360-degree sound experience is rapidly evolving. Both music and sound effects come from the surround speakers. Since the movie Explorers (1984), the surround speakers have been dedicated left and dedicated right, allowing wonderful abilities to truly surround the audience and develop an ambience envelope that the audience sits within to enjoy the full soundtrack experience.

The dedicated speaker is placed at the rear of the theatre, thanks to the introduction of Dolby EX. It is meant for the hard assignment of sound effects that will perform behind the audience—for further envelopment—as well as pop-scare effects and dramatic swoop from rear to front aspect audio events.

Everyone knows that the home theatre has literally skyrocketed both in technology as well as the ability, in many cases, to present the theatrical experience more vibrantly (in the audio sense) than the hometown cinema. This literal tidal wave of home entertainment theatre development has demanded an audio encoding system that could properly place the prescribed audio channels to the correct speakers and do it with as little fuss or muss (as well as technical understanding) on the part of the consumer as possible.

Many home systems use a separate speaker on either side of their big screen television screens instead of the built-in speakers. The dialog is phantomed from the left and right speakers, creating an illusion of a center channel. More and more consumers are now buying a special center channel speaker and placing it either on top or just below the television screen, thus having a dedicated dialog signal assignment. This makes for a much fuller and more natural front dialog track experience than the phantom technique.

For many years home systems have had a surround system, where both the left and right rear speakers were fed by the same surround speaker signal, just as theatrical presentation was prior to the movie Explorers. But more and more consumers are taking advantage of the split-surround option and incorporating that into their home system as well.

A favorite of many consumers, especially those who love to irritate their neighbors, is the subwoofer speaker additive. They come in all prices and sizes, up to a 3,000-watt subwoofer that can just about move walls. This full-speaker system, for consumer venues, is what the 1 in 5.1 is all about.

Now, with Dolby EX and DTS-ES, the 5.1 rises one more notch, allowing consumers to place a dedicated rear surround channel just like they experience in the theatre. Technically, this raises the encode designation to 6.1, rather than 5.1, though this term has not officially taken hold as of the writing of this book. The truth of the matter is, variations have provided us with 7.1, and only technical variations will dictate how far this will evolve. Several years ago Tom Hollman (THX) told me that he was working on 10.1. Ten years from now I can just see two consumers standing around the off-the-shelf purchase shelf at their nearest dealer, arguing whether the 20.1 or 22.1 version is more satisfying for total immersion entertainment!

Channel Assignments

Channel 1: Center speaker (front)

Channel 2: Left speaker (front)

Channel 3: Right speaker (front)

Channel 4: Left-surround speaker(s) (rear left)

Channel 5: Right-surround speaker(s) (rear right)

Channel 6: Rear (Dolby EX) speaker (rear center)

Channel .1: Subwoofer (low-frequency effect)

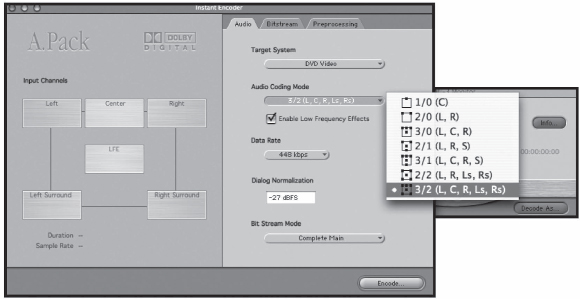

Figure 21.2 Dolby encode software that the user can matrix-encode his or her audio channels into any playback configuration listed in the submenu. The user simply presses the speaker button icon on the left and assigns the proper audio file to it.

THE QC GAME

One would not know it by looking at the sleek disk products coming out onto the market, but there are huge issues when it comes to quality control.

All DVD authoring facilities have a QC department, of course, but only a small percentage of DVD authoring is done with proper 5.1 playback room environments. Some DVD authoring companies simply have their QC techs (usually underpaid get-start trainees) handle the QC evaluation by listening to the soundtrack through headsets. As incredibly stupid as this sounds, it is no joke. You are going to have someone listen to and properly evaluate a 5.1 soundtrack (review Figure 20.2) through a left-right set of headsets?! I know, I know, the market advertises headsets claiming to play proper spatial 5.1 environment, but they simply do not.

You have just spent umpteen million dollars producing this motion picture; you have hired the best sound team you could to record the production sound, the best team you could to handle the post-edit challenges and sound design, and the best re-recording sound team you could to mix it. They worked thousands of hours to produce the best sound experience that they could, and now—now, you are going to entrust a quality evaluation to an underpaid get start trainee using HEADSETS! After all that, you really need to have someone listen to and evaluate a 5.1 soundtrack (review Figure 20.2) with proper equipment. Go ahead—play Russian roulette if you want to—but NOT ME!

To add insult to injury, there is a general plus or minus 4-frame sync acceptability. A top Hollywood film laboratory vice president actually admitted this to me, quote: “Plus or minus 4 frames is acceptable to us.” Ever wonder why those lips seem a little “rubbery” to you? Now you know. And I am not just talking about low-budget product. One major studio subcontracted their DVD authoring for a huge-budget picture to an independent firm and discovered that the DVD had been mastered with the audio channel assignments directed to the wrong speakers. This was a huge budget picture, by the way. The studio had to buy back all the DVDs and remaster, which cost them an extra several million dollars.

Here is a bit of warning for those who thought it was perfectly safe to watch DVDs on your computer. Much to the chagrin of a major (and I mean major) studio executive who watched a test DVD of his $100+ million epic motion picture on his personal computer, he found out that the DVD authoring service had contracted a virus in their system which was transplanted onto the DVD and as he watched the movie the virus transplanted itself into his own computer hard drive, eating away and destroying his computer files.

Unfortunately the world of DVD authoring is so misunderstood, like so many technical disciplines that are misunderstood, that there are few in the business who really know their own business. The before-mentioned studio put its foot down about the independent contractor that misassigned the audio channels of its major motion picture. The studio execs decided to build their own in-house state-of-the-art operation. Good idea, except for one problem: they did not hire the right person to head it up.

Over time the work literally was outsourced to independent contractors again because of mismanagement and technical ineptitude from the inside. A doctor may be a doctor by virtue of the initials M.D., but you do not hire a podiatrist when you need a brain surgeon. Consequently the studio found itself back where it started. Once again, quality and craftspersonship are being destroyed by throat-cutting and low-ball bidding, by studio decision makers who think they know what is going on and how it should be done (and seldom do) making decisions based on who-knows-who relationships and low-bid greed, rather than keeping the eye on the art form.

TOTAL IMMERSION OPPORTUNITIES

In addition to the obvious soundtrack mastering of linear entertainment product, such as authoring DVD media of motion pictures, rock videos, and the like, the need for sound event designers and audio authoring is rapidly expanding.

One of the most exciting emerging technologies for the future generation of entertainment venues is the total immersion experience. This is the next quantum step, with photo-realistic visuals fed to you via wraparound goggles, spherical-audio that is event linked to visual action and touch/temperature sensations phantomed throughout your nervous system—driven by complex algorithmic interdependent software that obey the laws of physics.

Interactive programs have evolved from crude digital color-block figures to mirroring reality. The technologies that need to drive the serious replication of such high-level audio-visual experiences require faster computers and mammoth amounts of high-speed access compressed visual and audio files. With every passing week the computers get faster, and the drive storage media get bigger, faster, and less expensive.

Several serious developers, thanks to Department of Defense dollars, are emerging with almost unbelievable audio-visual “scapes” that defy the boundaries of tomorrow's entertainment possibilities. The promises of 1980’s Brainstorm and Isaac Asimov's remote viewing from I Robot as well as countless science-fiction prognosticators of the past 100 years are finally coming to fruition.

Software programs have pushed the boundaries of realism, such as the seascape software that can replicate ocean waves as real as nature makes them. The operator simply fills in parameter requirements, such as water temperature, wind direction and speed, longitude and latitude, and the sea will act and react exactly as the laws of physics dictate. Another software program can replicate any kind of ship. The operator enters parameters such as historic era, wood, metal, displacement, size, cargo weight, design, etc. The ship will replicate out and ride the ocean wave program, obeying the laws of physics as its size and displacement require.

New body-scanning platforms can scan the human body down to a hair follicle and enter the images into the computer for action manipulation in real time, bringing forth a whole new reality of opportunities. You can now create whole epic scenes, limited only by the power of your imagination and your understanding of how to enter parameters into the multitude of programs that will work in concert to create the future vision that you have in mind. Today's war cry is: “If you can think it, you can make it!”

There will be an exploding market for the new “total immersion” sound designer who will be hired, along with his or her team of sound creators—what we may have once called the sound editor. These craftspeople, who will specialize on their own assignment audio events, which once created and factored into the entire audio construct of the project, will work in concert with each other—all obeying the laws of physics along with the virtual real visual replications to create the brave new worlds. After we come home from a long day at the office, we will want to unwind and relax by “jumping” into various “total immersion” entertainment scenarios.

Various new sensor interactive technologies are currently being developed that will allow you to “feel” the visual realities. You are already able to turn your head and change the aspect of your view, turning to see a big oak tree with its leaves rustling in the warm afternoon breeze. Now with 360-degree spherical-binaural audio, you will be interlinked to visual events that will play for you the realistic sound of deciduous leaves fluttering in the breeze; and through a device such as a wristband, embedded signals in the program will phantom the sensation of a warm gust of wind across your body. You will feel pressure as well as temperature in addition to seeing photo-realistic visuals and spherical sound.

Practical Application for Training Purposes

The armed forces believed that they could possibly save as many as 50 percent of their wounded if they could just train their combat personnel not to fear the act of being shot or seriously injured in action. They had a scenario developed for total immersion interactive, whereby their soldiers train in ambush scenarios with enemy forces. Realistic spherical-audio sells the distant weapon fire and the incoming flight of deadly bullet rounds. The phantom bullets strike the body, the first in the upper shoulder, the second in the left thigh. The sharp zip of other bullets flies past the trainee, striking and ricocheting off various surfaces (exactly linked and replicating the trainee's surroundings) around the soldier.

Now the wounded trainee has experienced as realistically as possible (short of really being shot) what it is like to be hit by incoming fire. Instead of reacting with the emotional side of our psyche, “Oh my God, I'm shot—therefore I am going to die,” the trainee is now trained to think, “Damn it! I've been hit! Now I have to problem solve how to survive!”

Mental attitude makes all the difference in the world. Our self-disciplined intellectual position will hold back the emotional side and discard the primal fears and spur the will to live.

Entertainment in Total Immersion

In the world of entertainment, one can just imagine the limitless applications to nervous system stimulation as triggered by nervous system events embedded in the total immersion program. New audio technologies are now being perfected that will change everything. What if I could give you a microphone and tell you that you do not have to try and mimic or sound like Clark Gable or Cary Grant, all you have to do is perform the dialog line with that certain lilt and timing of pace and performance. Your spoken words would then be brought into a special audio software and processed through the “Clark Gable” or “Cary Grant” plug-ins and out will come, voice printable, Clark Gable or Cary Grant.

Science fiction? Not at all. In fact, as of the writing of this book, a number of first step tests have already been accomplished. By the time this book is ready for its third edition I am sure that I will be updating this segment of the chapter to outline the specifics of the various software applications and how to use them.

This, of course, will change everything. Up to now, the visual cut-paste technique of integrating deceased celebrities into commercials and motion pictures (e.g., Forrest Gump, beer commercials with John Wayne, and Fred Astaire dancing with a vacuum cleaner) has been dependent on original footage. Yes, we have been able to morph the actor's face to be absolutely accurate for some time; that is no trick at all. It is the human voice that has eluded us, and the use of voice mimics to impersonate the deceased actor has always been just detectable enough to make it useless for serious celebrity replication. With the advent of this new audio technology, however, the shutters will be thrown back on all of the projects that have wanted to bring an actor back to life to perform in a project and give a performance that he or she had never given before. We are literally on the eve of a new evolution of entertainment opportunities utilizing these new technological breakthroughs.

These new opportunities (as well as the responsibilities) are staggering. By combining the technologies, one could create a total immersion entertainment venue whereby you could come home from a stressful day and decide that you want to put your total immersion gear on and activate, say, a Renaissance Faire program that would take you into an evening-long, totally realistic experience of being at a fifteenth-century festival on a nice spring afternoon with, of course, a spherical audio experience.

It only stands to reason that the more aggressive opportunists will develop programs where you could come home and put your total immersion gear on and make passionate love to Marilyn Monroe or Tom Cruise (depending on your sex and/or preference) or whoever else is literally on the menu.

Needless to say, there will be obvious exploitation used with this new technology as well as amazing mind-blowing opportunities to do things we could not otherwise do, such as a total immersion space walk or participate alongside Mel Gibson in the Battle of Sterling or scuba dive amid the coral reefs. Can you imagine what it would be like to turn an otherwise boring afternoon (say that you are snowed in at home or maybe you are just grounded by your parents) into an interactive educational scenario, such as sit around in a toga in the Roman Senate or participate in the lively debates in the House of Lords during Cromwell's time? Or be aboard the frigate USS Bonhomme Richard under the command of John Paul Jones in the fierce night engagement with the Serapis off the Yorkshire coast at Flamborough Head? You are a member of the crew helping to man the cannons and fight hand-to-hand combat in the grappling embrace of the two ships. Entertaining and extremely educational at the same time—what a concept!

All of this is going to need a new generation of sound craftspeople, developing and pushing the boundaries of how to design, develop, and bring to the consumer the most amazing audio event experiences you can possibly imagine.

AUDIO RESTORATION

To the inexperienced, “audio restoration” probably sounds like some salvation service, with medieval monks hunkered around their individual workstations working on would-be lost sound files. I doubt that they are monks, but this wonderful and amazing aspect of our industry is woefully misunderstood by far too many who may very well find that they desperately need this kind of work. Though there are a number of off-the-shelf programs with no-noise, broadband, declick, or other algorithmic spectrographic resynthesizer applications, only experienced and well-trained veterans can properly empower the use of such software. There is nothing worse than a bull swinging a sledgehammer in a china closet rather than a Dutch master painter using a sable brush!

There are few very fine audio restoration services. To salvage nearly 85 percent of the production track of Frank & Jesse, and clean out dominant fluorescent ballast hums from over 50 percent of Doctor Jekyll and Ms Hyde, as well as on several other occasions, I have personally used John Polito of Audio Mechanics (Burbank, California), one of the world's leaders among a multitude of audio restoration services.

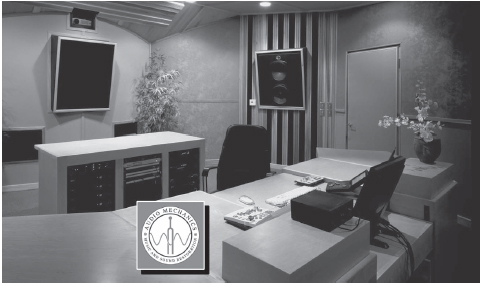

Figure 21.3 Audio Mechanics’ 5.1 mastering studio.

Audio Mechanics features two mastering rooms designed for 5.1 from the ground up: a live room and vocal booth for recording and ADR, and a stereo mastering control room. Their rooms are a well-thought-out design with complete audio/video/data integration among all rooms and facility-wide Equi-Tech balanced power to eliminate grounding problems. The centralized equipment room allows rooms to share resources efficiently and quickly recover from equipment failures.

This state-of-the-art 5.1 mastering room features instant room tuning presets to adapt to the project: a “flat” setting for music mastering; a Dolby-certified film setting for print mastering; a screen-compensation EQ setting for the center channel when the Stuart screen is lowered for picture projection; and a delay compensation for the digital video projector.

Up to 50 different room tunings can be stored to simulate various listening environments. The speaker system features an ITU placement of five matched dual-15″ Pelonis Series mains, based on a Tannoy 15″ dual concentric phase linear driver integrated with a super-fast low-frequency driver and a super tweeter that extends the frequency response up to 80 kHz. JBL dual-18″ sub-woofer delivers a thundering “point-one punch.” The room is not only gorgeous, but the sound is amazing, and the imaging is perfect. Like all great craftspersonship, it is all about the details.

Figure 21.4 shows a view of the rear wall of the room featuring a rear-center channel soffit and Pelonis Edge technology bass trapping with a first-ever acoustic RPG Peg-Board, utilizing a mathematically randomized hole pattern to permit near perfect bass absorption along with an evenly distributed diffusion above 500 Hz.

The tools required for sound restoration and noise removal are extremely sophisticated and infinitely complex. Without the proper experience and talent, results can vary from mediocre to just plain awful. Audio Mechanics has more combined experience and talent with these tools than anyone in the world, and their track record proves it. Producers, directors, mixing engineers, and dialog editors come to Audio Mechanics because they know they will get the best results attainable.

Figure 21.4 Reverse view of Audio Mechanics’ 5.1 mastering studio.

Figure 21.5 Audio mechanic logo.

Sound Preservation and Restoration

Research evaluation is the most important step in preservation. The three Rs of restoration—research, research, research! Any information you can gather about the original sound production, the genealogy, quality, and condition of existing elements, will enable you to pick the best possible elements for the restoration. The goal is to find the best sounding, most original element. Oftentimes the best element will be one that is not readily available. The engineer should evaluate the elements’ physical condition and audio quality, and document the findings. Select the best element or elements for transfer.

Transfer (the second most important step in preservation). Always use the best playback electronics and digital converters available. Prepare the element by carefully inspecting and, if necessary, cleaning and repairing. Mechanical modification of playback equipment can be used to accommodate shrinkage, warping, vinegar syndrome, reduced sprockets, roller heads, etc.

Listening environment (always important). The quality of listening environment is as important as the talent of the engineer. Care must be taken to make the listening environment appropriate for the type of work being performed. Use high-quality speakers and amplifiers appropriate for the type of sound work being performed. Make sure that the acoustics of the room are optimized. Just as important as the room itself, the engineer must know how the room translates to the environment the sound will be heard in.

Remastering (clean up, conform to picture, remix). Ninety-nine percent of remastering is now performed with digital tools. The current standard for digital audio restoration is 48 kHz/24-bit, but the industry is moving towards 96 kHz/24-bit. Digital tools are available to reduce hum, buzz, frame noise, perforation noise, crackle, pops, bad edits, dropouts, hiss, camera noise, some types of distortion, and various types of broadband noise including hiss, traffic noise, ambient room noise, motor noise. High-quality digital filters and equalizers can help balance the overall sonic spectrum. Digital audio tools are only as good as the engineer who is using them.

The experience and aesthetics of the engineer directly relate to the quality of the end result. Knowledge of the history of the original elements guides the engineer's decision process. For example, the restoration process would be quite different for a mono soundtrack with Academy pre-emphasis than it would be with a stereo LCRS format. Knowing whether a mono show was originally a variable-density track versus a variable-area track will also affect key decisions early on in the process. For picture-related projects, ensure that the restored audio runs in sync with picture. It may seem obvious, but make sure you are using a frame-accurate picture reference when checking sync. Oftentimes there are different versions of the picture available. The intended listening environment will determine the final audio levels.

Theatrical environments have a worldwide listening standard of 0 VU = 85 dB. This means that the sound level of a film should sound about the same in any movie theater. The music industry has not adopted a listening standard, so the level depends on the genre and delivery media. Until recently, digital audio final masters were delivered on digital audiotape. DAT, DA-88, DA-98HR (24-bit), and DigiBeta were used for film; while 1630, DAT, and Exabyte were used for the music industry. The problem with these formats is that they had to be transferred in real time and the shelf life of the tapes was anywhere from 1 to 10 years. High error rates were sometimes experienced within a single year. The industry has been moving toward optical disk and file transfer over the Internet for final digital delivery, with a preference for audio data files that can be copied and verified faster than real time.

The music industry uses Red Book audio CD-R with an optional PMCD format (Pre-Master CD), and recently DDP files (Disk Description Protocol) that can be transferred and verified over the Internet or via data CD-ROM or DVD-ROM. The film and video industries have been converging on Broadcast Wave Files audio files (BWF) on DVD-R, removable SCSI drives, FireWire drives, or transferred directly over the Internet via FTP. Higher capacity optical disk storage has recently become available with HD-DVD and Blu-ray (a.k.a. ProData for data storage).

Archiving (re-mastered and original elements). Save your original elements! Technology is continually evolving. Elements that seem hopelessly lost today may be able to be resuscitated 5 or 10 years from now. Save both the original elements and the raw digital transfer of the elements. The film industry routinely transfers the final restored audio to several formats. Analog archival formats include 35-mm variable area optical soundtracks and 35-mm Dolby SR magnetic tracks on polyester stock. Digital formats include BWF files on archival grade DVD-R, and digital Linear Tape-Open (LTO). DVD-ROM is a good choice because a high-quality archive-grade DVD-R has a long expected shelf life of 50+ years. They are, however, very sensitive to mishandling and scratch easily, which can cause a loss of data. LTO tape is popular because it is an open standard with backwards compatibility written into its specifications. It is widely supported and not owned by any single manufacturer, so it is less likely to become obsolete quickly in the ever-changing digital frontier.

Even though LTO is digital tape with a fairly poor shelf life, solutions exist to allow easy migration to newer and higher capacity tapes. Software verifies the data during migration. The music industry vaults their masters in whatever format is delivered. Because the manufactured optical disks are digital clones of the original master, they can rely on a built-in automatic redundant worldwide archive. Live data storage servers are another option for digital archiving masters. RAID storage (Redundant Array of Independent Disks) is perhaps the most proactive way to digitally archive audio. RAID is a self-healing format. Because RAID disks are always online, a computer can continually verify the data. If a drive in the array fails, a new unformatted drive can be put in its place and the RAID will automatically fill the drive with the data required to make the data redundantly complete. RAID storage is much more expensive than DVD-R and LTO.

A wise digital archivist would adopt two or more digital archiving formats, and create multiple copies of each using media from multiple manufacturers. Geographically separating multiple copies should also be adopted as a precaution in the unlikely event of a disaster.

John Polito has been at the forefront of digital sound restoration since its inception. After graduating in 1987 from Stanford University with honors in music and digital signal processing, Polito joined Sonic Solutions and helped define the field of digital sound restoration by assisting in the development of the first digital audio workstation for sound restoration. In 1991 he started Audio Mechanics, considered to be a world's leading sound restoration facility, with a reputation for maintaining the highest quality standards the field has to offer. For further information on Audio Mechanics as well as how to contact John Polito personally, please visit www.audiomechanics.com.

For a further demonstration of the audio work that John Polito has shared with us in this chapter, go to the interactive DVD provided with this book. Choose button #10 RESTORATION & COLORIZATION and a submenu will appear. Choose the AUDIO MECHANICS demo button and you can hear comparisons and examples for yourself.

Restoration and Colorization

Colorization in a book on sound? Yes, it might seem odd at first, but this entire chapter is about the ever-evolving world of emerging technologies and the future that we, craftspeople as well as producers and product users, are swiftly hurtling toward like a mammoth black hole in the galaxy of the entertainment arts.

Inexorabilis—the disciplines and artistic concepts come colliding together like two separate galaxies that criss-cross each other's determined path. Though you have read my touting that sound is more important than the visual image in a motion picture, I am the first to speak an opinion with regard to the colorization of film. A staunch resistor was I—until in late 1989 I saw one film, one film only that changed my thinking. John Wayne's The Sands of Iwo Jima was amazingly better than any of the childish smudge coloring that I had seen up until that time.

Figure 21.6 Legend logo.

Then, out of the blue, I happened to have a fateful conversation with an old colleague whom I had worked with a number of years ago at another cutting-edge firm (no longer in existence). I asked Susan Olney where she was working. She told me she was vice president of operations at an amazing, cutting-edge technology company based in San Diego, California.

In a few short conversations I found myself talking to Barry Sandrew, president and COO of Legend Films. Our conversation was almost like two lost brothers finding each other after years of separation. I told him that the only colorization effort I ever saw that gave me cause to pause was Sands of Iwo Jima. He chuckled as he responded, “That was my work.”

Well, of course it was. It had to be. As the conversation continued it became extremely obvious to me that the evolution of our art forms are, in fact, inexorably drawing all of us into a singularity of purpose and dedication—art form and the highest standards of craftspersonship to create artificial reality.

Barry sent me several DVD demos, parts of which I am pleased to share with you, as they are on the interactive DVD that comes with this book. Under button #10, RESTORATION & COLORIZATION, choose the LEGEND FILMS DEMO and I am sure that like myself, you will be amazed by what you will see. The interview of Ray Har-ryhausen is especially compelling in dispelling the standard artistic argument that we always hear against colorization, and he should know—he was there, he worked with these directors and artists. I cannot think of a professional and respected voice who can give a reason to rethink and appreciate this amazing process.

COLORIZATION: A BIASED PERSPECTIVE FROM THE INSIDE*

The technology of colorization has changed considerably since it first arrived on the scene in August 1985 when Markle and Hunt at Colorization Inc. released the 1937 production of Topper, the first colorized feature film. They used a system in which analog chroma signals were digitally drawn over and mixed with analog black-and-white video images. To put it more simply, colors were superimposed on an existing monochrome standard video resolution image much like placing various colored filters over the image.

Today, Legend Films, a leader in all-digital colorization, is working with black-and-white and color feature film at the highest film resolutions and applying long-form and short-form nondegrading restoration and a spectrum of color special effects with a brilliance and quality never before attainable. These technological advances are largely the result of my work in digital imaging and specifically digital colorization over the past 20 years.

However, the overall workflow and processing protocol for restoration and colorization evolved over several years beginning in 2001 by a very talented team of colleagues at Legend Films who built a machine that colorizes feature films, commercials, music videos, and new feature film special effects in the most efficient and cost-effective manner in the industry. Historical accounts of colorization from its genesis in the late 1980s and early 1990s is replete with a handful of highly vocal, high-profile Hollywood celebrities who adopted a vehemently anti-colorization stance. Some became so obsessed with the cause that it appeared their life's mission to rid the world of this new technology that was to them so evil and so vile that its riddance would somehow deliver them salvation in the afterlife.

Others much less vocal understood that the purpose of U.S. copyright law was to eventually make vintage films freely available to the general public after the copyright holder held the title as a protected monopoly for a fixed period of time. These laws are the same as patent laws, which eventually make inventions, drugs, and other innovations free to the public for competitive exploitation and derivation. There was a significant majority who saw colorization as a legitimate and creative derivative work and who recognized that colorization was actually bringing new life to many vintage black-and-white classics that were until then collecting dust on studio shelves or viewable on television only in the early morning hours. I believe the most balanced and accurate account of the technological evolution of colorization as well as the political and economic perspectives underlying the colorization controversy can be found in a critical essay by Gary R. Edgerton, “The Germans Wore Gray, You Wore Blue,” in IEEE Spectrum (Winter 2000). (Gary R. Edgerton is a professor and chair of the Communication and Theatre Arts Department at Old Dominion University.)

For me, one of many significant revelations in the IEEE Spectrum article is that the colorization controversy might have been largely avoided had Colorization Inc. continued the joint venture relationship they had already developed with Frank Capra to colorize three of his classics, including It's a Wonderful Life. When Markle discovered It's a Wonderful Life was in the public domain he dismissed Capra's involvement in the colorization of the Christmas classic and took on the project himself, seriously alienating Capra.

Edgerton, wrote the following, which is an extract from an R. Lindsey, May 19, 1985, New York Times article (pp. C1, C23)—“Frank Capra's Films Lead Fresh Lives.”

Capra did indeed sign a contract with Colorization, Inc. in 1984, which became public knowledge only after he began waging his highly visible campaign against the colorizing of It's a Wonderful Life in May 1985, when he felt obliged to maintain that the pact was “invalid because it was not countersigned by his son, Frank Capra, Jr., president of the family's film production company.” Capra went to the press in the first place because Markle and Holmes discovered that the 1946 copyright to the film had lapsed into the public domain in 1974, and they responded by returning Capra's initial investment, eliminating his financial participation, and refusing outright to allow the director to exercise artistic control over the color conversion of his films.

As a consequence, Colorization, Inc. alienated a well-known and respected Hollywood insider whose public relations value to the company far outstripped any short-term financial gain with It's a Wonderful Life, especially in light of the subsequent controversy and Frank Capra's prominent role in getting it all started. Capra, for his part, followed a strategy of criticizing color conversion mostly on aesthetic grounds, while also stating that he “wanted to avoid litigation … at [his] age” and “instead [would] mobiliz[e] Hollywood[‘s] labor unions to oppose” colorized movies’ without performers and technicians being paid for them again.

Edgerton succinctly sums up the controversy: “All told, the bottom-line motivation behind the colorization controversy was chiefly a struggle for profits by virtually all parties involved, although the issue of ‘creative rights’ was certainly a major concern for a few select DGA spokespersons such as Jimmy Stewart, John Huston, and Woody Allen, among others.”

The rest of Edgerton's article is historically spot-on accurate. However, in his conclusion Edgerton writes:

In retrospect, the controversy peaked with the colorization of Casablanca and then gradually faded away. Ted Turner recognized as early as 1989 that “the colorization of movies … [was] pretty much a dead issue” (G., Dawson “Ted Turner: Let Others Tinker with the Message, He Transforms the Medium Itself,” American Film, Jan/Feb 1989:36–39, 52). Television audiences quickly lost interest in colorized product as the novelty wore off completely by the early 1990s.

While certainly a reasonable conclusion for Edgerton to make in 2000 when he wrote the IEEE Spectrum article, I'm confident it will be judged premature given significant changes in the attitude of the entertainment industry, the emerging spectrum of digital-distribution channels available for entertainment of all types, and the advent of Legend Film's technological advances in both restoration and colorization.

From Brains to Hollywood

I first learned that people were creating colorized versions of black-and-white classic feature films in 1986 when I was a neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital engaged in basic brain research and medical imaging. My interest in colorization at the time was purely academic in nature. Indeed, a process that could create colorized black-and-white feature films where color never existed intrigued me. From the lay literature I understood the early colorization effort was accomplished using an analog video process. Consequently I did not delve much further into the early process because at the time I was not experienced in analog video but firmly entrenched in high-resolution digital imaging. When I saw the results of the analog process I was less than impressed with the quality but certainly impressed with the technological and innovative effort.

Digging further into the business rationale for colorization it was clear why the technology had become attractive even if the aesthetic value of the process was questionable. While the black-and-white version of a vintage film remains in public domain, the colorized version becomes a creative derivative work that (back in 1986) was eligible for a new 75-year copyright.

Coincidently, in the summer of 1986 George Jensen, an entrepreneur from Pennsylvania with the entertainment company American Film Technologies, approached me to develop an all-digital process for colorizing vintage black-and-white films which he hoped would become a major improvement over the current analog process. American Film Technologies had financed several failed development trials in an effort to create a digital colorization process that might capture the market. When approached by George to provide an alternative solution I suggested a novel direction to the problem that was significantly different from any of the failed attempts.

Given my background in digital imaging and my credibility credentials in academia, American Film Technologies decided to offer me a chance to develop their system. I considered the opportunity sufficiently low risk to leave academia for a period of time and take on an R&D project with company stock, a considerably higher salary than one can expect at a teaching hospital, and all the potential rewards of a successful entertainment startup company.

Part of my decision was based on the fact that George Jensen had assembled an impressive group of Hollywood talent, such as Emmy-nominated Peter Engle (executive producer, Saved by the Bell) and two-time Oscar winner Al Kasha (Best Song, honoring “The Morning After” from The Poseidon Adventure and “We May Never Love Like This Again” from The Towering Inferno), as well as Bernie Weitzman, former vice president/business manager for Desilu Studios and vice president of operations for Universal Studios. This brought me additional confidence that the company was heading toward the mainstream entertainment industry. I saw George Jensen as a visionary in that he realized one could colorize a huge library of proven classic black-and-white films in the public domain and in the process become a Hollywood mogul based solely on technology.

The problem that stood in his way was the development of advanced digital-imaging technology and the acquisition of original 35-mm film elements that would be acceptable in overall image quality to capture digitally for colorization and VHS release. His search for a superior, all-digital process ended soon after we met. My lack of experience in analog video was a huge advantage because I believe I would have been biased toward developing a more advanced analog solution and ultimately the system would have been less successful. Instead, I started from scratch and created a digital colorization process that was technologically much different from existing systems but markedly superior in final product.

I believe my strength was coming at the problem from a totally different and perhaps naïve perspective. I was not a video engineer and had very little knowledge of the field. Consequently, there were some in the entertainment industry that told me my concept wouldn't work and advised me to go back to studying brains.

The Early Digital Process

Colorization was a designer-created color transform function or look-up table that was applied to underlying luminance or gray scale values of user-defined masks. Each mask identified objects and regions within each frame. In other words, instead of simply superimposing color over the black-and-white image like the old analog processes, the color was actually embedded in the image, replacing the various levels of black and white with color. This permitted a great deal of control over color within each frame and automated the change of color from one frame to the next based on changes in luminance. Once a designer created a reference frame for a cut it was the colorist's job to make certain the masks were adjusted accurately from frame to frame. The colorists had no color decisions to make because the designer-created look-up tables intimately linked the color to the underlying gray scale. All that the colorist was required to do was manually modify the masks to fit the underlying gray scale as it changed due to movement every 24th of a second from frame to frame. However, because each mask in each frame had to be viewed by the colorist and possibly manually modified, the number of masks allowable within each frame had to be limited.

Of course from a production-cost standpoint the more masks in a frame the more the colorists had to address and the longer each frame took to be manually modified the greater the cost to colorize. Consequently, using this method, the number of mask regions per frame in the American Film Technologies system was ultimately limited to 16. Because the process was highly labor intensive the user interface was designed to be very simple and very fast so that process could be outsourced to a cheaper labor market.

Within 5 months I had a working prototype and a demo sufficient to premier at a Hollywood press conference. The late Sid Luft, Judy Garland's ex-husband and manager, became a great personal friend and major supporter of colorization. He provided American Film Technologies with some of our early black-and-white material from Judy Garland concerts and television shows which we incorporated into a demo. Most of the material originated on relatively poor-quality 2″ videotape but the digital color was such an advancement over the analog process that it appeared stunning to us. Apparently it also appeared stunning to the press at a conference held across the street from Universal Studios in April 1987. When Frank Sinatra appeared with baby blue eyes you could hear the amazed reaction of those assembled.

The majority of articles that resulted from that press conference were favorable and indicated that colorization had finally come of age. In reality we had a long way to go. The real proof of concept didn't happen until November 1987 when we successfully produced the first all-digital colorized film, Bells of St. Mary's, for Republic Pictures. Much of the technology was refined and developed during that period of production and during the production of several feature films thereafter.

American Film Technologies took over the colorization industry within one year following the release of Bells of St. Mary's though Jensen's vision of creating a library of colorized films never really materialized. We learned that the best 35-mm prints at the time were held by the studios or by a very close-knit subculture of film collectors, so we became largely dependent on the major studios as work-for-hire clients. Those clients included Republic Pictures, Gaumont, Universal, Disney, Warner Bros., CBS, ABC, MGM, Turner Broadcasting, and many others.

In the early 1990s American Film Technologies and its competitors eventually faded away because each company overbuilt for what was essentially a limited market. Once Turner completed colorizing his “A” and “B” movie hit list, colorization essentially dried up. I believe that both the technology and the industry premiered and peaked 20 years too early. Today there is affordable computer horsepower to automate much of the process at the highest resolutions and in high-definition as well as film color space. In addition, using reliable outsourcing resources, particularly in India, virtual private networks can make it seem as though a colorization studio in Patna, India is next door to our design studio in San Diego. The affordability and, most important, quality of colorization product has advanced to a technological plateau.

Figure 21.7 Barry B. Sandrew, Ph.D., president and COO of Legend Films.

The Rationale for Colorization Today

The early days of colorization were a wakeup call to studio asset management directors and archivists, many of whom saw their studio libraries neglected for over half a century. However, the very early studio asset managers and archivists (if they existed) were not at fault. Indeed it was a matter of budget, studio culture, and lack of foresight. As a result over half of the films that were ever produced in the United States are gone today. Not because they have deteriorated over time, though this was also a contributing factor, but because the studios threw many of their film negatives in the trash!

There were actually rational excuses for this mass destruction of our film heritage. No one in the 1920s through the late 1940s saw the enormous impact of television on our lives and culture. Certainly, the idea of tape recorders in every home and later DVD players and soon high-def DVD players was as distant as a man landing on the moon … probably more so because digital video entertainment in the home could hardly be envisioned. No one anticipated Blockbuster, Hollywood Video, or Netflix, where films of every genre and era can be rented. There was no sign that the cable industry and the telcos would be laying the groundwork for downloading high-definition films to home digital disk recorders and viewable on the average consumer's 50-inch high-definition monitor with 5.1 surround sound, as they are today.

In the early years, studio feature films had a theatrical run and those films that had a significant return on the studio investment were likely saved. Those that did not were eventually thrown out to make shelf space for newer films. The idea of films having an after-life was foreign to only the most Nostradamus-like among studio executives. It's ironic that it took colorization, with all its controversy, to focus mass attention on the need to restore and preserve our film heritage. With so many diverse digital distribution outlets for entertainment product today and a renewed desire for proven vintage entertainment, the studios now have a great incentive to restore their classic black-and-white film libraries. Several have called on Legend Films to colorize selected classic black-and-white titles in an effort to make them more attractive to new generations of audiences.

Indeed, by now much of the furor over colorization has subsided and special effects specialists, archivists, creative producers, and iconic Hollywood talent are embracing the process. Digital distribution outlets cry for content that is economical yet proven profitable. What better time for colorization to reemerge, and now in high definition. The studios realize that new film production is typically high cost, high risk, and low margin. Colorization of proven evergreen (having timeless value) classic feature films is low cost, low risk, and high margin over time.

Legend Films, Inc.: Building a System for the 21st Century

In 2000 I met Jeff Yapp, former president of International Home Video at 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment and later president of Hollywood Entertainment (Hollywood Video stores). He was a major proponent of colorization for at least a decade before I met him and he always pointed to the old but valuable 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment collection of colorized Shirley Temple films that were re-released in the late 1990s as fully remastered for broadcast and VHS sales. Those colorized classics turned into one of 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment's most successful home video campaigns. Jeff understood the added value of colorization if it could be done correctly, at high-definition, and with a color vibrancy and quality never before seen. He asked whether I could create a more automated method of colorization that would be “light years ahead of the look of the old colorization processes.” Fully equipped with the latest and most economical computer horsepower, major advances in software development, and broadband connectivity, I was 100 percent certain it could be done.

Restoration of the black-and-white digitized film is the first step in the colorization process. In order to create the best-looking colorized product, it is essential to start with the best black-and-white elements with the best dynamic range. We search for the best quality 35-mm elements and then digitally capture every frame in high-definition or various film formats. While the colorization is ongoing we put each frame through the Legend Films’ proprietary restoration process. The software is semi-automated, using sophisticated pattern recognition algorithms, and the user interface is designed to be easily adaptable to unskilled outsourcing labor markets.

The colorization system had to be sophisticated enough to do the heavy lifting of correct mask placement from frame to frame with little decision making or direction by the actual colorist. Speed, efficiency, and, most of all, quality were the essential ingredients. With the cost of high-powered technology at an all-time low, and with reliable PC networking I went to work. The result was a semi-automated colorization system, in which there were no color restrictions, and the number of masks per frame could be essentially unlimited. Legend Films currently has 10 international patents that are either published or pending along with a full-time R&D team that is constantly evolving the system to meet and overcome new production challenges.

Figure 21.8 Barry Sandrew going over Q&A colorization points to David G. Martin, CEO and Sean Compton, QA Manager on 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment's Heidi.

One objective was to create an intuitive user interface that would make much of the sophisticated technology underlying the color design, colorization, and restoration software transparent to the user and consequently built for unfettered creative design as well as speed and efficiency.

In the case of a feature film, the entire movie is captured digitally in high-definition or film resolution. The resulting digital frames are then dissected into cuts, scenes, characters, locations, etc. Once the entire film is broken down into its smallest components, a series of design frames is selected to serve as a color storyboard for the film. The design process involves applying many different colors for various levels of shadows, mid-tones, and highlights. With 16 bits of black and white or 64,000 levels of gray scale available for each frame, the amount of color detail that can be applied is enormous. At American Film Technologies only 256 gray scale values were available for each frame. In the case of color film, Legend Films can apply color effects at a resolution of 48 bits of color or 16-log bits per red, green, and blue channel. Pure hues are not common in nature, but in earlier digital colorization processes, single hue values were the only way to apply color to various luminance levels.

In the Legend Films process, color is dithered in a manner that mixes hues and saturations semi-randomly in a manner that makes them appear natural, particularly for flesh color and different lighting situations. While this sounds complicated, the design process is actually unencumbered by the underlying technology, allowing the designer to focus on the creative aspects of the colorization process rather than keeping track of masks or how the computer interprets the data. Once the designer has established the color design, it becomes locked into a cut and scene so that no additional color decisions need to be made during the actual colorization process. The color automatically adjusts according to luminance levels.

A second key ingredient of the Legend Films’ color effects process is a method of applying color effects from frame to frame in a manner that requires little skill other than an eye for detail. Once the color design is established for the entire film, at least one frame per cut in the film is masked using the lookup tables appropriate for that cut. This key frame is used as a reference to move the color masks appropriately from one frame to the next. This process of moving masks from one subsequent frame to the next has been largely automated in the Legend system using many sophisticated pattern recognition algorithms that are activated with the press of a space bar. Making the process even easier, only the foreground objects (i.e., objects that move independently of the background) are addressed at this stage. The backgrounds are colorized and applied automatically in a separate step. The only labor-intensive aspect of this process is the high level of quality assurance we demand for each frame. This requires that a colorist monitor the computer automation and make slight adjustments when necessary. Any adjustments that the colorist makes updates the computer to recognize those errors in future frames so in effect it learns from prior mistakes. As a consequence of this proprietary computer intelligence and automation, the colorization software is readily adaptable to any economical labor market regardless of skill level. In fact, a person can be trained to become a colorist in little more than a day, although it takes a few weeks to become proficient.

The third key ingredient of the Legend colorization process is the automated nature of background color effects. Each cut in the film is processed using Legend's proprietary utility software to remove the foreground objects. The background frames for the entire cut are then reduced to a single visual database that includes all information pertaining to the background, including offsets, movement, and parallax distortion. The designer uses this visual database to design and subsequently apply highly detailed background color automatically to each frame of the cut where the foreground objects have already been colorized. This sophisticated utility enhancement dramatically cuts down the time required for colorizing, essentially removing the task of colorizing the background from frame to frame. Since backgrounds are handled in design, the colorist need only focus on foreground objects and the designer can place as much detail as he or she wishes within the background element. Complex pans and dollies are handled in the same manner.

Once the color of the foreground and background elements are combined, the entire movie is rendered into 48-bit color images and reconstructed using SMPTE time code for eventual layoff to high-definition or 35-mm film.

Colorization—A Legitimate Art Form

Figure 21.9 Reefer restored two-panel black and white only presentation.

In 2006, colorization matured into a legitimate art form. It provides a new way of looking at vintage films and is a powerful tool in the hands of talented color designers for realizing what many creative contributors to our film heritage intended in their work.

A color designer typically looks at an entire film and creates a color storyboard that influences the way the film will ultimately look like in color. Our designers are experienced in many aspects of production including color theory, set design, matte design, costumes, and cinematographic direction. Their study and background research of each film is exhaustive prior to the beginning of the design process. Once into the film, the designer uses visual cues in an attempt to interpret what the original director had intended in each shot.

If the shot focuses on a particular individual, object, or region the focal length of that shot within the context of the dialog and storyline will often provide the reason it was framed in a particular way. Using color the designer can push back all or parts of the background or bring forward all or parts of the object, person, or region of interest that is necessary to achieve the desired effect.

The designer can also enhance the mood by the use of warm colors and/or cold colors as well as enhance the intended character of particular actors with flesh tones and highlights. Lighting can be used in a spectrum of ways to increase tension or create a more passive or romantic mood in a shot. Certainly the possibilities for influencing the audience's reaction, mood, and perception of scenes are enormous when using color appropriately.

India Is the Future

To paraphrase Legend Films’ Thomas L. Friedman (The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-first Century, 2006), the world of entertainment production is getting flatter by the day. Outsourcing to Canada was yesterday; today it's China and India. I've become particularly enamored with India because we've maintained a highly efficient and professional production facility there for the past three years. I never would have considered maintaining a satellite production studio halfway around the world in Patna, India, and 12½ hours ahead of us; but with broadband connectivity and a virtual private network, Legend Films is functioning 24 hours a day. We receive color data from India every morning that is applied to our high-definition frames in San Diego. We review that work during the day and send QC notes for fixes, which follow the next day. The work ethic and work quality of this largely English-speaking part of the world has been a major asset to Legend Films.

Our primary studio in India is partitioned into 16 smaller studios with 10 to 15 colorist workstations in each. High-quality infrared cameras are mounted in each studio so that we can see the work being done and communicate with the colorists over any production issues. The result is that Uno/Legend Studio in Patna and Legend Films in San Diego are one virtual studio that works in sync around the clock, around the world. We are now adding an additional studio in India at Suresh Productions in Hyderabad to increase our overall output and offer a more complete service package globally to filmmakers. The new facility acts as a third element of the Legend virtual studio working in tandem with our Patna studio. It concentrates on film restoration but also has digital intermediates and color-grading capabilities as well as the most advanced high-definition telecine, editing, and laser film scanning equipment. The facility also includes a complete soundstage resource as well as audio suites for voice looping and sound effect sweetening.

Figure 21.10 Special FX wizard, Ray Harryhausen, directs the color design for Marian Cooper's She with Creative Director, Rosemary Honath.

Hyderabad is one of the major centers of the film industry in India and as such has a large middle-class and rather affluent and highly educated population. The world is changing and professionals in all aspects of the entertainment industry, particularly in production, must be aware of this change. Don't be in denial.

The Second Coming of Colorization

In the past three years we have restored and colorized more than 50 films in high-definition or film resolution and we currently have another 50 in the pipeline. 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment has elected to use the Legend Films’ process to revitalize the entire Shirley Temple catalog of films that were originally colorized in the 1980s—and early 1990s. We've also colorized The Mark of Zorro and Miracle on 34th Street for 2005 and 2006 releases, respectively, for 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment.

Many in the creative community of vintage Hollywood are looking to correct the gaps in available technology when their films were first produced. Other contemporary producers, directors, and special effects supervisors are using colorization to bring cost savings to what are already skyrocketing production costs.

Ray Harryhausen

Even when color film was first available the cost often outweighed the value since, unlike today, the theatergoing audience back then was quite accustomed to black-and-white films. A case in point is Marian C. Cooper's sci-fi classic, She. Cooper intended that the film was to be originally shot in color, and both the sets and costumes were obviously designed for color film. However, RKO cut Cooper's budget just before production and he had to settle for black and white.

It wasn't until 2006 that Ray Harryhausen chose Legend Films’ advanced colorization technology to re-release She in the form that Cooper envisioned it—in vibrant color! Ray spent days in our design studio working with our creative director to select appropriate colors for the background mattes so that they retained or in most cases enhanced the realism of a shot. He knew exactly what Cooper would have been looking for had he been sitting in the designer's chair. The result is outstanding and, because of Ray's involvement and creative input, the film is one of the most important colorization projects ever produced.

Ray Harryhausen has become a staunch proponent of Legend Films’ colorization process and has asked both Warner Bros. and Sony Home Entertainment to allow him to work with Legend to colorize his black-and-white classics, including Mighty Joe Young, Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, 20 Million Miles to Earth, It Came from Beneath the Sea, and Earth us the Flying Saucers. When he originally produced these films, he envisioned them in color but was constrained by studio budgets and the status of film technology at the time. He told me that it was difficult to do realistic composites with the existing color film stock. Today, using Legend Films technology he can design his iconic fantasy monster films into the color versions he originally intended.

The Aviator

Martin Scorsese used Legend Films to produce the Hell's Angels opening scene in The Aviator. He also used Legend's technology to colorize portions of The Outlaw with Jane Russell and many of the dogfight scenes in Hell's Angels. While many of the dogfight scenes were done using models, other scenes were simply colorized footage of the Hell's Angels feature film. Obviously those scenes would have been very difficult to reproduce as new footage. For a tiny fraction of the cost to recreate the models and live-action footage of key scenes, he received from Legend Films all the colorized footage he needed which Rob Legato, FX supervisor, blended seamlessly into The Aviator.

Jane Russell

I remember showing Jane Russell the seductive scene in The Outlaw that made her a star and was used in Scorsese's The Aviator. Of course it was the first time she had seen it in color. Although the scene was only about 8 to 10 seconds long and she was viewing it on my 15″ laptop, she loved the way her red lips looked, the natural flesh color of her face, and the accuracy of her hair color and its highlights. She later did a running commentary of The Outlaw for the Legend Films colorized DVD library in which she was very frank, with typically Jane Russell sass, reminiscing about her experiences with Howard Hughes. That Legend Films’ title is scheduled for an April 2007 release date.

Whenever I speak to Jane she expressed a very strong desire to colorize The Pink Fuzzy Nightgown (1957) owned by MGM. That was the last starring film role for the Hollywood icon, which she co-produced with her former husband, Bob Waterfield. Jane considered that film her favorite starring role next to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. The film was originally intended to be a film noir, which Jane wanted directed and shot in black and white. She was fortunate to have that option. However, it evolved into a comedy and looking back, she has always regretted her decision to shoot it in black and white, and today is lobbying the studio to allow her to design the film in color using the Legend Films’ process. Colorization and her personal involvement in reviving the title will add considerable asset value to a film that is certainly not a revenue-producer at the moment. To have Jane Russell color design and provide commentary on one of her favorite films was fulfillment of a longheld wish by a beloved and significant Hollywood icon.

Terry Moore

Terry Moore is an actress who was married to Howard Hughes and starred in films such as Mighty Joe Young, Shack Out on 101, Why Must I Die, Man on a Tightrope. She was nominated for a best supporting actress Academy Award for her role in Come Back, Little Sheba. Terry is a dynamo who, at 76, is probably more active today than ever in her career. She became a “believer” in colorization and a very dear friend of mine when Legend Films colorized A Christmas Wish in which she co-starred with Jimmy Durante.

During that process she provided running commentary on the colorized version for our DVD release in 2004. She was so engaged with the process that she commented that Howard Hughes would have loved the Legend Films’ technology and would have wanted to redo his black-and-white classics. Terry and Jane are happy that we were able to accommodate Hughes with our colorized version of The Outlaw. The two Hollywood stars collaborated on the video commentary for the Legend Films DVD of The Outlaw in which Moore interviews Russell and the two compare notes on Howard Hughes. They are certain he would have colorized that film if he was alive today.

Shirley Temple Black

What can you say about Shirley Temple Black? I had the awesome privilege of visiting her at her home in the San Francisco Bay area 3 years ago. I wanted her to compare how the 1990s colorization of Heidi looked (that had been sold for the past 10 years on VHS) and how it looked in the 2003 colorization by Legend Films in high definition. We set up a high-def workstation in her house and set it up in her living room. I'll never forget Shirley's reaction when she saw the switch from black-and-white to color. She initially said, “That looks really good in black-and-white,” but when the color popped in she said, “Wow, that looks great!” I believe she understood at that moment that colorization using advanced technology brings new life to great classics.

Shirley and Legend soon entered into a partnership to restore and colorize original Shirley Temple films and TV programs that she always showed to her kids during birthday parties but which were stored in her basement after they were grown. Shirley had dupe negatives of her Baby Burlesk shorts, the very first films in which she appeared when she was 3 and 4 years old. She also had 11 hours of The Shirley Temple Storybook, which were produced when she was a young woman. She acted with Jonathan Winters, Imogene Coco, and many other famous comedians and actors of the day in the most popular children's stories.

Those 11 hours were the last starring and producing project in which she was involved. The classic TV programs are rich in color and held up well as quad tapes. We restored each 1-hour show and released both the Baby Burlesk and Shirley Temple Storybook as a set that is currently being sold as The Shirley Temple Storybook Collection.

Conclusion

While there will always be detractors, the fact that we fully restore and improve the original high-resolution, black-and-white digitized film elements in the process of colorization should satisfy most purists. Furthermore, we always provide the restored black-and-white version along with the colorized version on each Legend Films DVD. In a very real sense, colorization and the increased revenue it generates subsidize the restoration of the original black-and-white feature film.

The bottom line: Colorization applied to public domain vintage films is a derivative work that deserves attention, as a valid interpretation of earlier studios’ work-for-hire. In that regard it is separate and distinct from the original work and should be allowed to stand on its own. In 2006, colorization has matured to a level where it is a legitimate art form. It is a new way of looking at vintage films and a powerful tool in the hands of a knowledgeable color designer for commercials, music videos, and contemporary feature film special effects.

- Barry B. Sandrew, PhD, president, and COO of Legend Films

You can review the video demo which includes Ray Harryhausen sharing his views and commitment to colorization as well as the numerous comparisons that have been discussed by Barry Sandrew on the interactive DVD included with this book. Choose button #10, RESTORATION and COLORIZATION; choose LEGEND FILMS VIDEO DEMO, and I am sure that you will also enjoy the LEGEND FILMS GALLERY of comparison stills.

IT IS ALL UP TO YOU

Your creativity and your dedication to your art form are limited only by your imagination and your personal commitment to quality in whatever craft you choose.

Thank you for your patience and open mindedness in reading this chapter as well as the entire book.

Now go forth and be creative.

* The text for this entire section was provided by Barry B. Sandrew, PhD, Legend Films, Inc.