Chapter 7

Picture Editorial and the Use of the Sound Medium

THE BASTION OF ABSOLUTES

You may wonder why I am going to first review the traditional “film” procedure of receiving, syncing, and preparing dailies for the picture editor to commence the creative process of editorial storytelling. The reason is twofold. First, it is important to understand the process, because, in a real sense the discipline of the process has not changed, only the technique and medium. The second reason is that sooner or later, much to your surprise you will find yourself in need of knowing how things were done, because there are millions of feet of film in vaults, and thousands of feet being sifted through on a daily basis for all kinds of reasons, everything from resurrecting a film to execute a director's cut, to film restoration, to assembling footage shot decades ago for developing valuable “behind-the-scenes” programs for the bonus materials options on today's DVD reissues.

When Terry Porter, over at Disney, handled the remixing challenge of the original Fantasia, elements that were nearly 50 years old had to be carefully brought out of film vaults, inventories checked, elements prepared, and old technology playback systems refreshed to be able to accomplish such a task.

Film restoration is a huge career opportunity for those who become infected with the love and devotion to not only saving classic film from being lost, but restore it back to its original glory. In order to even start to understand how to get your arms around such projects, you have to understand how they were structured and prepared in the first place.

Except for the fact that very few crews actually edit with film anymore, the technique and discipline of exacting attention to detail has not changed a bit. In fact, you have to be even more disciplined in that a computer only knows what you tell it. If you enter improper data, you cannot expect it to problem solve your mistake of input for you. So you need to pay attention to how and why we do things. It is as I keep harping at you—the tools will change every five minutes, but the Art Form does not.

FROM THE LAB TO THE BENCH

From the moment daily film and mag stripe transfers arrive from the laboratory and sound transfer, to the moment when the edge code number is applied to both picture and track after running the dailies with the director and picture editor, is the most critical time for the regimentation and precision that the film endures. It is during the daily chore of syncing up the previous day's workprint and corresponding soundtrack when the assistant picture editor and picture apprentice must practice their skills with the strictest regard to accuracy and correct data entry.

The film arrives, and the picture assistant and apprentice swing into action, racing to sync up all daily footage in time for that evening's screening. Errors made at this point in lining up the picture and soundtrack in exact sync are extremely difficult to correct later. Seldom have I seen sync errors corrected once they have passed through the edge-coding machine.

Odd as it may sound, the technique and discipline of syncing film dailies are not as straightforward as they may sound. For some reason, film schools allow students to learn to line up and sync their film dailies on flatbed editing machines. I do not care what any film school instructor tells you—a flatbed editing machine is not a precise machine. Veteran editors and especially prized professional picture assistants also will tell you that flatbed editing machines are inaccurate by as much as plus-or-minus 2 frames! (Most moviegoers notice when dialog is out of sync by 2 frames.)

This is not an opinion or one man's theory. This is a fact, without question; those who even try to debate this fact are showing the laziness and incompetence of their own techniques. The only way to sync film and mag track precisely is to use a multi-gang synchronizer. Because so much hinges on having picture and mag track placed in exact sync to one another, it never ceases to amaze me when someone knowingly uses anything but the most accurate film device to maintain rigid and precise sync.

Before you can actually sync the dailies, you must first break down all the footage, which I now describe in detail. As you wind through the rolls of workprint, you develop a rhythm for winding through the film very quickly. You watch the images blur by, and every so often you notice several frames that “flash-out.” These were overexposed frames where the aperture of the camera was left open between takes and washed out the image. These flash-out frames are at the heads of each take. Pause when you come across these flash-out frames, pull slowly ahead and, with the help of a magnifying loop, determine precisely which frame the slate sticks meet as they are snapped together. That is where the clap is heard on the mag track.

Use a white grease pencil in marking the picture once you have identified the exact frame where the slate marker has impacted. Mark an “X” on that frame of film where the sticks meet, then write the scene number, angle, and take number (readable from the slate) across the frames just prior to the “X” frame. Find the scene and slate number on the lab report form included with the roll of workprint, and mark a check next to it.

Roll the workprint quickly down to the next group of flash-out frames, where you pause and repeat the process. After you have marked the slates on the entire roll of workprint, take a flange (a hub with a stiff side to it, or, if you like, a reel with only one side) and roll the workprint up. Watch for the flash-out frames, where you cut the workprint clean with a straight-edge Rivas butt splicer. Place these rolls of picture on the back rack of the film bench, taking time to organize the rolls in numerical order. You should probably practice how to wind film onto a flange without using a core. For the beginner, this is not as simple as you might think it is, but you will quickly master the technique.

After you have broken down all the picture, take a synchronizer with a magnetic head and commence breaking down the sound transfer. The sound transfer always come tails out. Take the flange and start rolling the mag track up until you come to the ID tag. This is an adhesive label, usually ¾” wide by a couple of inches long. The transfer engineer places these ID tags on the mag film just preceding rolling the scene and take the ID tag identifies. Break off the mag, keeping the ID tag. Then place the mag track into the synchronizer gang and lock it down; lower the mag head down to read the mag stripe. Roll the track forward. You hear the production mixer slate the scene and take, then you hear a pause, followed by off-mike words from the director. Within a few moments, you hear a slate clap. Continue to roll the mag track through until you hear the director call, “Action.”

It is at this point that most sync errors are made, because not all head slates go down smoothly. During the course of the picture a host of audio misfires occur. Sometimes you hear a voice call to slate it again; sometimes you hear the assistant director pause the sound roll and then roll again. Also, you can mistake a slate clap for a hand slap or other similar audio distraction. If you are shooting multiple cameras, be careful which slate you mark for which workprint angle, unless all cameras are using a common marker, which is rare. Sometimes the slate clap is hardly audible; a loud, crisp crack often irritates the actors and takes them out of character.

Once you are satisfied that you have correctly identified the slate clap, use a black Sharpie marker to make a clean identification line across the frame exactly where the sound of the clap starts. Do not use a grease pencil in marking the slate impacts on the mag track. Once a grease mark has been placed on a magnetic track, it can never be completely rubbed off. The grease cakes up on the sound head and mars the soundtrack. Use a black Sharpie marker to mark the exact impact point on the mag track. Have no fear, the ink from the Sharpie does not harm or alter the sound on the mag track.

Remember that 35-mm film has four perforations to the frame, which means that you can be 1/96th of a second accurate in matching sync. The more dailies you sync up, the more you will study the visual slate arm as it blurs down to impact. You will get a sense of which perforation in the frame is the best choice. You are now changing the mechanical technique of syncing dailies into an art form of precision.

Using the black Sharpie, write the scene, angle, and take number just in front of the slate clap mark on the mag track in plain sight. Roll up the head end of the mag track back to the ID tag and place the roll of mag track on the back rack of the film bench alongside the corresponding roll of picture.

Once you have finished, you will have a back rack filled with rolls of picture and track. You will have rolls of WT (wild track) with no picture. You will have rolls of picture with no track. Check the labels on the rolls of picture that do not have any corresponding rolls of soundtrack. They should all have a designation of MOS (without sound) on the label.

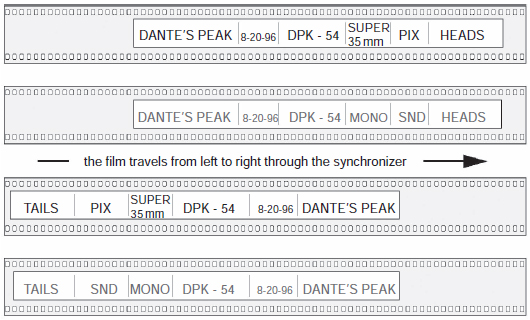

Figure 7.1 HEAD and TAIL leaders. This is standard labeling for daily rolls.

Check the lab reports and sound reports. All of the material inventory should have your check marks next to them. If not, call either the laboratory or the sound transfer facility to order the missing workprints or mag tracks.

You are now ready to start building your daily rolls. Professional picture editorial departments always build the daily rolls starting with the smallest scene number and building out to the largest. By doing this, the director and picture editor view an entire scene and its coverage starting with the master angle; then they review the Apple (“A”) angle takes, then the Baker (“B”) angle takes, then the Charley (“C”) angle takes, and so on. You also review scenes in order; for instance, you would not screen 46 before you would screen 29. It helps to begin the process of continuity in the minds of the director and picture editor.

Once you have built a full reel of picture and track, put head and tail leaders on these rolls. It is traditional to use a black Sharpie marker for the picture label, and a red Sharpie for the sound label. With this kind of color coding, you can identify a picture or sound roll from clear across the room. Head and tail leaders should look much like the labels shown in Figure 7.1.

HEAD AND TAIL LEADERS FOR FILM

To the far right of the label, “HEADS” is listed first, then “PIX” (for workprint, abbreviated from “picture”), or “SND” (for mag track, abbreviated from “sound”).

The next piece of information to add to the head label is the format in which the picture is to be viewed. This is rather helpful information for your projectionist, as he or she must know what lens and aperture matte to use. After all, it's not as easy as saying, “Oh, we shot the film in 35.” Okay, 35 what? The picture could have been shot in 1:33, 1:85, 1:66; it could have been shot “Scope” or “Super-35” or any number of unusual configurations.

Do not write the format configuration on the sound roll, but list what head configuration the projectionist must have on the interlock mag machine. The vast majority of film projects have monaural single-stripe daily transfers, so list “MONO” for monaural. However, some projects have unusual multichannel configurations, such as those discussed in Chapter 5. When using fullcoat as a sound stock medium, picture editorial can use up to six channels on a piece of film.

The next label notation to make is the roll number. Each editorial team has its own style or method. Some list the roll number starting with the initials of the project, making roll “54” of the feature Dante's Peak list as “DP-54” or “DPK-54.” Some do not list the initials of the show, just the roll number. Some editorial teams add a small notation on the label, showing which of that day's daily rolls that particular roll is. “DPK-54” could have been the third of five rolls of dailies shot that day, so it would be shown as “3-of-5.”

Most editorial teams list the date. Last, but not least, list the title of the film. The tail leaders should have the same information, but written in the reverse order.

I always make my head leaders first on ¾” white paper tape, then I apply the labels onto color-coded 35-mm painted leader. Different picture assistants use their own combinations of color-coded painted leader, but the most common combinations are yellow-painted leader for picture and red-painted leader for sound. I run 5 or 6 feet of the painted leader, then I splice into picture fill, as picture fill is considerably cheaper per foot than painted leader.

Roll the picture fill down about 20 feet on both picture and sound rolls. At this point, cut in an Academy leader “HEADER” into the picture roll. The Academy leader roll has the frames well marked as to where to cut and splice.

The frame just prior to the first frame of the “8” second rotation is called “Picture Start.” This frame could not be marked more clearly: it means just that—“PICTURE START.” At this point, apply a 6” strip of ¾” white paper tape, covering 5 or 6 frames of the Academy leader with the “Picture Start” frame right in the middle. With a black Sharpie, draw a line across the film from edge to edge, on the top and bottom frame line of the “Picture Start” frame. Place another strip of ¾” white paper tape, covering 5 or 6 frames of the picture fill leader of the sound roll. Again, with a black Sharpie draw a line across the film from edge to edge somewhere in the middle of the tape, as if you are creating a frame line on the tape. Count four perforations (equaling 1 frame) and draw another line across the film from edge to edge. Draw an “X” from the corners of the lines you have drawn across the tape, so that this box has a thick “X” mark. With a hand paper-punch carefully punch a hole right in the center of this “X” on both rolls.

Pssst! The punched hole is for light to easily pass through, making it much easier for the projectionist to seat the frame accurately into the projector gate, which is traditionally a rather dimly lit area.

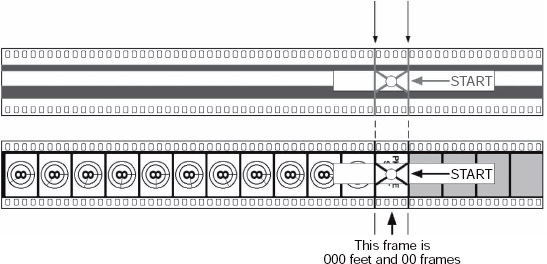

Figure 7.2 The start mark; the exact frame and synchronization between the picture and sound tracks are critical.

The Start Mark

Figure 7.2 illustrates the start marks. Snap open the synchronizer gangs and place the picture leader into the first gang, the one closest to you so that the “X,” which covers the “Picture Start” frame, covers the sprocket teeth that encompass the “0” frame of the synchronizer. Close the gang until it locks shut. Place the sound leader into the second gang, the one with the magnetic sound head on top. Align it over the “0” frame in the same fashion as the picture roll. Close the gang on the sound roll until it locks shut.

From here on, these two pieces of film run in exact sync to one another. Anything you do to this film, you do to the left of the synchronizer. Do nothing to the right of the synchronizer; to do so would change sync to the two rolls of film and therefore cancel out the whole idea of using a synchronizer (sync block) in the first place.

The biggest mistake beginners make when they start syncing dailies is that they pop open the gangs for some reason. They think they must open them to roll down and find sync on the next shot. Not only is this not necessary, but it is a phenomenal screw-up to do so. Remember, once you have closed the synchronizer gangs when you have applied and aligned your start marks, never ever open them—even when you finish syncing the last shot of the roll. (Don't ask me why people open the synchronizer like that, I am just reporting common mistakes that I have often seen.)

After the last shot, attach an Academy leader “TAIL” on the end of the picture roll and fill leader on the end of the sound roll. When the Academy leader tail runs out, attach a length of fill leader and run the two rolls an additional 15 or 20 feet. Roll them through the synchronizer and break or cut the film off evenly on both rolls; then apply your tail leader identification tapes accordingly. You have just finished syncing dailies for the first roll of the day—great! Move on to the next roll. Time is running out, and you still have nearly 3,000 feet of film to go.

I am sure many of you are sloughing off this process of syncing dailies. Film is dead—nonlinear is where it is at, right? I would counsel caution for those who would love to sound the death knell of film. Years ago, when videotape came out, I read articles that predicted the demise of film—yet film is still with us. A few years later, David Wolper was shooting a miniseries of Abraham Lincoln in Super 16mm. I remember reading various professional publications of the time sounded the death knell for 35-mm film—yet, again, 35-mm film is still with us, and healthier than ever, even with the advent of “high-definition” and “24-P” technologies offered today.

When studios all shot their films on location, I read articles about the death of the traditional sound stages. Not only do we still have sound stages, but within the studios and independent arenas there is a resurgence of building sound stages throughout the world. Stages that had been converted for mass storage suddenly booted their storage clients out and reconverted back to being sound stages.

Not too long ago, I also read of the supposedly impending death of old-fashioned special-effects techniques, such as glass paintings and matte shots. These types of effects, it was claimed, were no longer necessary with the advent of computergenerated technologies. By the way, not only have we experienced a rebirth of glass paintings and matte shots, but a renaissance is also under way of the older “tape-and-bailing-wire” techniques.

Every so often I am still approached by various clients seeking shoot-on-film/cut-on-film options to produce their new projects. Several clients had worked in nonlinear and had decided it was preferable for them to return to film protocols.

Lately I have had the privilege to talk to many of my colleagues and other film artisans with whom I usually do not communicate on a daily basis. The broad base of film medium practitioners, in both editorial and sound re-recording applications, pleasantly surprised me. I would not sound the death knell for film-driven postproduction just yet.

“But We Are Nonlinear!”

One should be cautious not to slip into a factory-style mentality when it comes to the quality and technical disciplines that your dailies deserve. Just because a laboratory offers you a sweet deal for “all-in” processing, syncing, and telecine transfers does not guarantee technical excellence. More than one producer has found himself having to pay out considerable extra costs to have work done over again, rather than being done correctly to start with.

Precise attention to detail is most crucial at this exact point in the filmmaking process: the syncing of the dailies and the creation of the code book. It is shocking to witness the weeks of wasted work and the untold thousands of squandered dollars that result when the picture assistant and apprentice do not pay attention to detail and create a proper code book. I cannot overemphasize the importance of this moment in the process. The code book becomes the bible for the balance of the postproduction process. Any experienced supervising sound editor or dialog editor will confirm this. Once you have performed a sloppy and inaccurate job of syncing the dailies, it is nearly impossible to correct.

With today's nonlinear technologies and the promise of faster assemblies from such advanced software applications as OMF and PostConform, these tasks become nearly automatic in nature. If you sync sloppily or enter misinformation in the directory buffer, you nullify the ability of OMF or PostConform to work correctly. Remember, a computer only knows what you tell it. If you tell it the wrong number, it only knows the wrong number. It's the cliche we always banter about, “junk in, junk out.” You can be the hero, or you can be the junk man.

THE CODE BOOK ENTRY

For some reason, many inexperienced picture assistants and apprentices think that once they get the sound onto the mag film transfer for the KEM or into the computer for the picture editor, that is the end of it. What further need would anyone have to know about sound rolls and all that? It's in the computer now, right? Wrong. On more than one picture where the inventory was turned over to me for sound editorial, I was shocked to find that either no code book whatsoever existed or that the code book was only filled out regarding negative. After all, the crew did understand, at some point, that a negative cutter would be needed to assemble the original negative together for an answer print. However, when I looked to the sound rolls and all information regarding sound, nothing was filled in. The excuses for this ran the gamut, all of which were just that, excuses.

In our industry, things work the way they do for a reason. Entry spaces are under certain headings for a reason: to be filled in! Fill in all the entry spaces. Fill in all of the codes for negative, sound roll number as well as edge code numbers. If in doubt, ask. It is best to check with sound editorial to confirm what requirements are needed from picture editorial so that sound editorial will have a complete code book at turnover. After picture editorial has finished the director's cut and is locking the picture for sound editorial turnover, a team of sound craftspersons and negative cutters depends on your thorough and accurate code book log entries.

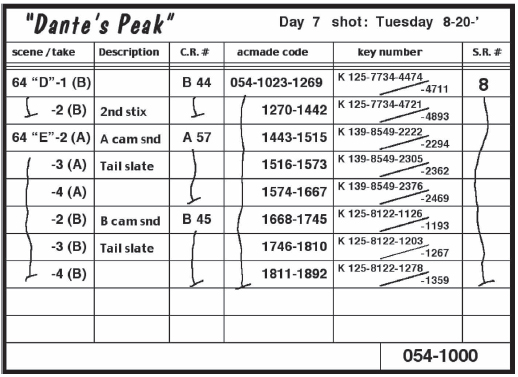

Figure 7.3 depicts a typical page from a code book generated by the picture editorial team. Note that the title of the film, number of day of shooting, followed by calendar date of the shoot, are listed at the top of the page. Note that the edge code series number is listed at the bottom of the page. When you three-hole-punch the page and start building up a thick binder, it is much easier to simply flip through the edges of the pages to search for the edge code number than if it were at the top.

The “Scene/Take” number is the first item listed on the far left. A “Description” entry is for the assistant editor to make important notes, such as “Tail slate,” “2nd stix” (for “Sticks”), and, if the audio transfer comes from a different source on the “B” camera than from the “A” camera (“B cam sound”), notes make information quick and efficient to find.

The “C.R.#” is where the camera roll number is listed. Note that the picture assistant precedes the roll number with which camera. This greatly aids in such tasks as syncing dailies, where the assistants verbally call out their assigned camera slates:

Figure 7.3 The code book. This is the bible of data by which all production picture and soundtrack can be found.

• “Camera ‘A’ marker” (followed by a slate clap)

• “Camera ‘B’ marker” (followed by a slate clap)

• “Camera ‘C’ marker” (followed by a slate clap)

How are you, the picture assistant, going to know which slate clap on the mag roll syncs up with which workprint picture shot from three different cameras simultaneously? Of course, you could pick one, sync it, and lace it up on a Moviola to see if the actor's lips flap in sync. What if the action is far enough away that a 3 × 4 inch Moviola screen is not big enough for you to see sync clearly enough? What if the much larger KEM screen is not big enough either?

You would probably eventually figure it out, but it is good to know how, for those oddball shots that missed seeing the slate clap or for when there is not a slate at all. I promise that you eventually will cut sound in late because the assistant director did not give the sound mixer enough time to warm up or to follow production protocol in waiting until the mixer calls “speed” back to him before action proceeds. You will have several seconds of silence before sound comes up, but the entire visual action has been shot. And, of course, who can forget those occasions when they tell you they will “tail slate” the shot, and then, during the take, the negative runs out in the camera before the slate can be made? Like that's never happened before.

You must find some bit of sound. Do not look for anything soft. Look for sudden, instant ones that make a precise point. An actor claps his hands with glee in the middle of the sequence, and there is your sync point. I have often used the closing of a car door, even the passing footsteps of a woman walking in high heels (of course, figuring out which heel footfall to pick was interesting). Knowing how to sync when production protocol goes afoul is important, but you do not want to spend your time doing it unnecessarily. You must develop a fully thought-through methodology of how to handle dailies given any number of combinations, inclusive of weather, number of cameras, mixed camera formats, mixed audio formats, use of audio playback, splitting off of practical audio source, and so forth.

The next entry is for the edge code number, listed here in the figure as the “acmade code” (the numbers discussed in Chapter 6 that are applied to both the picture and sound precisely after your daily screening). In this case, the editorial team chose to code its picture by the camera roll method, rather than individual scene-and-take method. This method is commonly referred to as “KEM rolls.”

For exhibition purposes, note that the first number always is 054 on this page, as this daily roll is #54. The second number is the last four digits that appear at the head of each shot, followed by a dash; the third set of numbers is the last four digits that appear at the end of each shot. Scene 64 “D” take 1 starts at 054-1023 and ends at 054-1269, plus or minus a foot for extra frames. You can instantly tell that this shot is 246 feet in length, which means that it is 2 minutes, 45.5 seconds long.

The next entry is the “Key number,” the latent image number “burned” into the negative by the manufacturer. This is the number your negative cutter looks for to image-match the workprint and negative, or, if you cut nonlinear, from your EDL. Its from-and-to numbering entry is just like the edge code number entry, only the last four numbers are entered that appear at the end of the shot.

The last entry is the sound roll number (“S.R. #”). Unless you want to have your sound editorial crew burning you in effigy or throwing rocks at your cutting room, you are well advised not to forget to fill in this blank.

One of the biggest and most serious problems in code book assimilation occurs when the picture assistant and/or apprentice do not make entries clear and legible. I often have trouble telling the difference between “1” and “7” and distinguishing letters used for angle identifications.

With today's computerized field units (such as the Deva, Fostex, Aaton, or Sound Devices 744t), much more data entry is done right on the set, as the camera is rolling. In many respects, this is very good. Information is fresh in the minds of the production mixer and boom operator. The loss of precious code numbers is less likely, especially when the production is using time code smart slates. Conversely, all this can lull the editorial team into a false sense that they do not have to pay as strict attention to data entry and the code book. Again, a computer is only as good as what you tell it. If misinformation is put into it, unwinding it and getting it straight again is incredibly difficult and time consuming, often adding extra costs to the production. If for some reason the fancy time code and software “wink out” or “crash,” you are dead in the water. When it works, a computer can be wonderful, but nothing replaces a trained professional's eyes and ears in knowing what must be done and doing it correctly and efficiently. The better your code book, the smoother the postproduction process that relies on it. It is just that simple.

THE DANGER OF ROMANTIC MYTHOLOGY

I have been both amazed and dismayed hearing film students talk about “cutting-in-the-camera” and other techniques and regarding cinematic history and mythology as if they were doctrine to adopt for themselves. These romantic remembrances really belong in the fireside chats of back-when stories; they are only interesting tales of famous (and sometimes infamous) filmmakers whose techniques and at times irresponsible daring dos that have no place in today's filmmaking industry. Mostly, critical studies professors who were neither there at the time nor have any knowledge of the real reasons, politics, and stresses that caused such things, retell these stories. Sure, it's fun to tell the story of John Ford on location in Monument Valley: upon being told he was seven pages behind schedule, he simply took the script, counted off seven pages, and ripped them out as he told the messenger to inform the executives back at the studio that he was now back on schedule. Do you think, though, that John Ford would dump seven pages of carefully written text that was a blueprint for his own movie? Some actually tell these mystical antidotes as if they had constructive qualities to contribute to young, impressionable film students, who often mistake these fond fables for methods they should adopt themselves.

THE POWER OF COVERAGE

The most important thing a director can do during the battlefield of production is to get plenty of coverage. William Wyler, legendary director of some of Hollywood's greatest pictures (Big Country, Ben-Hur, The Best Years of Our Lives, Friendly Persuasion, Mrs. Miniver) was known for his fastidious style of directing. It was not uncommon for him to shoot 20 or 30 takes, each time just telling the crew, “Let's do it again.” The actors struggled take after take to dig deeper for that something extra, as Wyler usually would not give specific instructions, just the same nod of the head and, “Let's do it again.”

Cast members tried to glean something from their director that might finally allow them to achieve whatever bit of nuance or detail Wyler had envisioned in the first place. As usual, though, precious little would be said except, “Let's do it again.”

Not to diminish the fabulous pictures he made or his accomplishments as a director, but the truth of the matter is William Wyler shot so many takes because he was insecure on the set. He did not always know if he had the performance he was looking for when it unfolded. What he did know and understand was the postproduction editing process. He knew that if he shot enough coverage his picture editor could take any particular scene and cut it a dozen different ways. Wyler knew that the editing room was his sandbox to massage and create the picture he really envisioned.

After closer examination, it is easy to understand why the job of picture editor is so coveted and sought after. After the director, the picture editor is considered the most powerful position on a motion picture project. Some even argue that, in the case of a first-time director or a director possessing even the perception of having a tarnished or outdated resumé, the picture editor is at least equal to if not more powerful than the director.

I have been in strategy meetings where a heated argument arose among studio executives over who would handle the picture editorial chores. The picture editor does more than just assemble the hundreds of shots from over 100,000 feet of seemingly disorganized footage. For example, a sequence taking 1 minute of screen time and portraying action and dialog between two characters usually appears to occur in one location cinematically. In actuality, the sequence would have been broken down into individual angles and shot over the course of days, even months, due to appropriate location sites, availability of actors, and other considerations. Sometimes what seems to be one location in the movie is actually a composite of several location sites that are blocks, miles, or even continents apart. Some actors who appear to be in the same scene at the same time performing against one another actually may have never performed their roles in the presence of the other, even though the final edited sequence appears otherwise.

LEANDER SALES

“As an editor, you are deciphering performance, and being that I have this training as an actor just helps me that much more when I am looking at those various takes of film and deciding which performance feels better.” Leander continued:

It is all about the performance. To me, I think that it is what editing is about. Of course, there is a technical aspect to it, but it is about a gut-level response to what I see on screen when I analyze the dailies.

So that's where it started, in drama. But that experience just led me into editing, and I love it. Because in editing you get a chance to work with everything—you get a chance to work with the work of the screenwriter, because often times you are cutting things out and adding things in—looping and ADR. You're working with the cinematographer's work, you're cutting things out and putting them back in. You're working with the production sound recordist's work—everything.

Figure 7.4 Leander Sales, film editor and editing faculty at the North Carolina School of the Arts-School of Filmmaking. (Photo by David Yewdall.)

A lot of times it gives you a chance to show the director things that he or she didn't see. Being an editor allows you to be objective. Because when the director is on set, often times he doesn't see certain things because he is so worried about other things. But as an editor, who is not on set, it allows me that objectivity.

Those are the moments that you look for. Those are the moments that actors look for, those true moments. You just feel it, and you can't repeat it—it just comes. That's the reason why Woody Allen says he never loops, or Martin Scorsese says he won't loop a certain scene because he says you can't recreate that emotion, because you don't have the other actor to bounce off of. It makes a huge difference.

Another important thing for a film editor, I feel, is just to live—life. You have to understand emotions, behavior—because basically that is what you are looking at when you are studying those performances. You are looking for the emotional context that you are trying to distill a truth and honesty. The more you live, the more it helps you to get to that truth. I lived in Italy for awhile, and I have traveled in Africa. Over there just helped me to understand life, and it opened so many doors for me as far as interest and just experimenting with things and trying to, I guess, see where I fit into the big picture of the world. That's important—how you fit into the big picture. That goes back to editing you see. You cut this little scene, but how does it fit into the big picture?

Editors are the only people who really get a chance to see the film from the first scene in dailies through to the release prints. I love that process. It's seeing the baby born, and then you put it out into the world.

MARK GOLDBLATT, A.C.E.

“Inappropriate editing can destroy a film,” declares Mark Goldblatt, A.C.E. Like so many of today's top filmmaking talents, Goldblatt learned his craft while working for Roger Corman on B-films like Piranha and Humanoids from the Deep, learning how to creatively cut more into a film than the material itself supplied. Goldblatt went on to cut Commando and The Howling, then vaulted into mega-action spectacles such as The Terminator and Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Rambo II, True Lies, Armageddon, Pearl Harbor, and X-Men: The Last Stand, as well as the space epic Starship Troopers. He said:

The picture editor must be sensitive to the material as well as the director's vision. On the other hand, the editor cannot be a “yes man” either. We should be able to look at the dailies with a fresh eye, without preconception, allowing ourselves to interface with the director, challenging him or her to stretch—to be open to trying new ideas. Sometimes you have to work with a director who has an insecure ego, who can't handle trying something new, but the good ones understand the need for a robust and stimulating collaboration.

Figure 7.5 Mark Goldblatt, A.C.E., picture editor.

When the picture editorial process is completed properly, the audience should be unaware of cuts and transitions. It should be drawn into the story by design, the action unfolding in a precise, deliberate way. “Consistency is vital,” comments Mark Goldblatt.

The actor performs all of his scenes out of order over a period of weeks, sometimes months. It's very difficult to match and reduplicate something they shot six weeks apart that is then cut together and played on the screen in tandem. Sometimes you have to carve a consistent characterization out of the film, especially if the material isn't there to start with. You have to help build sympathy for the protagonist. If we don't care for or feel compassion for the protagonist, the film will always fail. If the audience doesn't care what happens to our hero, then all the special effects and action stuntwork money can buy will be rendered meaningless.

COST SAVINGS AND COSTLY BLUNDERS

Knowledgeable production companies bring in the picture editor well before the cameras start to roll. The picture editor's work starts with the screenplay itself, working with director, writer, producer, and cinematographer to determine final rewrite and to examine tactics of how to capture the vision of the project onto film. At this time, the decision of film-editing protocol is decided, and whether to shoot on film and cut on film (using a Moviola or KEM) or whether to shoot on film and digitize to cut on a nonlinear platform such as Final Cut Pro or Avid.

Close attention must be paid to the expectations for screening the film, either as a work-in-progress or as test screenings. Needs also are addressed for screening the film in various venues outside of the immediate cutting environment. Is the project a character-driven film without many visual effects, or is it filled with many visual special effects that require constant maintenance and attention?

These considerations should and do have a major impact on the protocol decision. The choice of whether to cut on film or nonlinear (and if nonlinear, on which platform) should not be left to the whim or personal preference of the picture editor. The decision should serve the exact needs and purposes of the film project. Not too long ago, I was involved in a feature film that wasted well over $50,000 because the project had left the choice of the nonlinear platform to the picture editor. The collateral costs required for its unique way of handling picture and audio files cost the production company thousands of dollars that would not have been spent if the appropriate nonlinear platform had been chosen for the project requirements.

Vast amounts of money also have been saved by not filming sequences that have been pre-edited from the screenplay itself, sequences deemed as unnecessary. Conversely, the opposite also is true. A number of years ago, I supervised the sound for a feature film that had a second-generation picture editor (his father had been a studio executive) and a first-time director. The film bristled with all kinds of high-tech gadgetry and had fun action sequences that cried out for a big stereo soundtrack. Halfway through principal photography, the director and picture editor deemed that a particular scene in the script was no longer relevant to the project, and, by cutting it, they would have the necessary money to secure a big, rich stereo track.

The producer was caught off-guard, especially as he had not been factored into the decision-making process, and threw a classic tantrum, demanding the scene be shot because he was the producer and his word was absolute law. The director was forced to shoot a scene everybody knew would never make it into the picture. The amount of money it took to shoot this scene was just over $100,000! Consequently the picture could not afford the stereo soundtrack the director and picture editor both had hoped it would have.

All who wondered why this film was mixed monaurally have now been given the answer. All who do not know to what film I am referring, just remember this horror story for a rainy day—it could happen to you. By authorizing the extra bit of stop-motion animation you really want or an instrumental group twice as big as your blown budget can now afford, you or those in decision-making capacities can wipe out what is best for the picture as a whole by thoughtless, politically motivated, or egotistical nonsense.

MILLIE MOORE, A.C.E.

Shoot the Master Angle at a Faster Pace

Millie Moore, A.C.E., once said:

I love master shots, and I love to stay with them as long as possible, holding back the coverage for the more poignant moments of the scene. However, to be able to do that, the master must be well staged, and the dialog must be well paced. If the dialog is too slowly paced, you are limited to using the master only for establishing the geography of the actors and action. The editor is forced to go into the coverage sooner simply to speed up the action, rather than saving the closer coverage to capture more dramatic or emotional moments. At one time or another, every picture editor has been challenged to take poor acting material and try to cut a performance out of it that will work. A good picture editor can take an actor's good performance and cut it into a great performance.

“My work should appear seamless,” remarks Millie Moore, picture editor of such projects as Go Tell the Spartans, Those Lips, Those Eyes, Geronimo, Ironclads, and Dalton Trumbo's Johnny Got His Gun. “If I make any cuts that reveal a jump in continuity or draw attention to the editing process, then I have failed in my job. An editor should never distract the audience by the editorial process—it yanks them right out of the movie and breaks the illusion.”

Figure 7.6 Millie Moore, A.C.E., picture editor.

Planning and executing a successful shoot is handled like a military operation, with many of the same disciplines. The producer(s) are the joint chiefs-of-staff back at production company headquarters. The director is the general, the field commander, articulating his or her subjective interpretation of the script as well as his ideas to manifest his vision on-screen. His or her lieutenant commanders—first assistant director, unit production manager, and production coordinator—hold productive and comprehensive staff meetings with the department heads, i.e., casting director, production designer, costume designer, art director, director of photography, sound mixer, picture editorial, grip and electrical, stunt coordinator, safety, transportation, craft services, and so forth.

From the first read-through to the completion of storyboards with shot-by-shot renderings for complex and potentially dangerous action sequences, literally thousands of forms, graphs, maps, breakdowns, and call sheets are planned and organized, along with alternate scenes that can be shot if inclement weather prohibits shooting the primary sequences.

Like a great military campaign, it takes the coordinated and carefully designed production plan of hundreds of highly experienced craftspeople to help bring the director's vision to reality.

Whether the film is a theatrical motion picture, television show, commercial, music video, documentary, or industrial training film, the basic principles don't change. Coverage should still be shot in masters, mediums, and close-ups with total regard for “crossing the line” and direction of action. Tracking (dolly) shots and crane shots must be carefully preplanned and used when appropriate. Many of today's movies suffer from the belief that the camera must be constantly moving. More often than not, this overuse of the camera-in-motion without regard to storytelling becomes weary and distracts the audience from the purpose of a film—to tell the story—or what I call the MTV mentality.

The editing style is dictated by the kind of film being made and the actual material the editor has. The picture editor knows which style is most appropriate after he or she has reviewed each day's footage and assimilated the director's concept and vision. Explains Mark Goldblatt:

You can take the same material and cut it any number of styles, changing dramatically how you want the audience to respond. You can build suspense—or dissipate it, setting the audience up for a shock or keep them on the edge of their seat. It's all in how you cut it. I can get the audience on the edge of their seat, realizing danger is about to befall the hero, because the audience sees the danger, and all that they can do is grip their seats and encourage the hero to get the hell outta there—or I can lull them into thinking everything is fine, then shock them with the unexpected. It's the same footage—it's just the way I cut it.

The picture editor's job is to determine which style is appropriate to that particular scene in that particular film. The picture editor may cut it completely differently for some other kind of film. The experienced picture editor will study the raw material and, after due consideration, allow it to tell him or her how it should be cut; then the editor just does it.

THE NONLINEAR ISSUE

Goldblatt continues:

There's a mythology to electronic editing. Don't misunderstand me, digital technology is here to stay—there's no going back—but there is a common misperception of the advantages. The technology makes it much easier to try more things. Let's face it, when you can do more things, you try more things. This way the editor can have his cut, the director can have his cut version, the producer can have their cut version, the studio can have their cut version(s) (often more than one), and, of course, they want the audience test screenings the very next day!

The problem is that working in digital doesn't give you as much time to think about what you're doing. When we used to cut with film on Moviolas and splice the film together with tape, we had more time to think through the sequence—you know, problem solving. In digital, we can work much faster, so we sometimes don't get the chance to think the process through as thoroughly. Nowadays, you see a number of movies that obviously look as if they had not been given the opportunity to completely explore the potentials and possibilities of the material, often without respect of postproduction schedules being totally out of control.

Many editors regard this problem as “digital thinking”—conceptualizing driven by the executive perception that digital is cheaper. Unfortunately, most studio executives who currently make these kinds of creative decisions are not trained in the very craft they impact.

“I think that the editorial process is given short shrift since the coming of electronic editing,” comments Millie Moore.

Because it is faster to cut electronically, less time is being scheduled for the editorial process. That could be fine if all else stayed the same; however, such is not the case. While postproduction schedules are shrinking, many directors are shooting considerably more footage per scene—the more the footage, the more time it takes the editor to view and select.

Also, because it is so fast to cut electronically, the editor is being asked to cut many more versions of each scene, which is also time-consuming. Compressing postproduction schedules while increasing the workload defeats the advantage of electronic editing. Although it may be faster, it does not create the “art form” of editing that takes know-how and time. The more you compress the time schedule, the more you crush the creative process.

There is no doubt that digital is here to stay. However, there needs to be a greater awareness of what we have lost in the transition. Only when the time-tested values of film editing are honored will digital technology fulfill its potential. This starts at the grass roots level—film students who understand that digital manipulation is not the art form. It is a tool, just like the Moviola—it just works differently.

Years ago sound editors didn't have magnetic stripe to cut sound; they cut optical track, having to paint their splices with an opaque fluid to remove pops and ticks that would otherwise be read by the exciter lamp in the sound head. When magnetic-stripe technology came along in the early fifties, it didn't change technique and principles of creative sound editing or sound design. It was a new tool to make the job easier. Now digital has come along to accelerate the process of cutting picture as well as sound. The technique and principles of how you cut a scene or design sound have not changed—we're just using a new kind of tool to do the job.

SOUND AND THE PICTURE EDITOR

Millie Moore, A.C.E., at one time contemplated her career:

Prior to pursuing a career in the picture editing arena, I was a postproduction supervisor and an associate producer making documentary films for Jack Douglas. We were the first people to use portable ¼” tape. Ryder Sound had always handled our sound facility transfer and mixing requirements. Loren Ryder had brought in the Perfectone, which was the forerunner of the Nagra, which was manufactured in Switzerland. Ryder Sound used to come up to Jack Douglas's office where we would shoot the introductions to the show.

Millie was head of all postproduction for Jack, turning out 52 shows a year as well as a pilot. Eventually, Millie was sent down to Ryder Sound to learn how to use the Perfectone herself so that Jack did not have to always hire a Ryder Sound team for every need. For some time, Millie was the only woman sound recordist in Hollywood, using this new ¼” technology from Europe.

On more than one occasion, when Millie would go to Ryder Sound to pick up recording equipment, Loren would ask her what kind of situation she was heading to shoot that day. Moore said:

He would often suggest taking along a new microphone that they had just acquired or some other pieces of equipment that they thought might be of value. In short order, I became experienced in various kinds of microphones and amplifiers—of course, I spent half my time on the telephone, asking questions of the guys back at Ryder.

I ended up teaching other people to use the equipment for Jack, especially when we went global in our shooting venues. Jack wanted me to move up to a full-fledged producer, but I turned him down. Frankly, I didn't want to live out of a suitcase.

It was then I decided that I wanted to move over to picture editing. It became very satisfying. I was working on several projects at once, either hands-on or as a supervising consultant for Jack. If there was anything really special that needed care, he and I would go into a cutting room and close the door and go over the material together.

It was very challenging for us, as we shot on both 16-mm and 35-mm film. On-location material was shot in 16-mm, and interviews were shot in 35-mm, so we had to combine these two formats. For a long time, I was the person who had to do the optical counts.

It was time to move on. Millie wanted to move into features, but in those days it was extremely hard for women to get lead position jobs, especially under union jurisdictions.

The independently produced Johnny Got His Gun was Millie's first feature film. The producer, who had worked at Jack Douglas's, wanted Millie to handle the Dalton Trumbo picture, an extremely powerful antiwar film:

Every director with whom I worked was a new learning experience. However, I feel that I learned the most from working with Michael Pressman. He and I were still young when we first paired up on The Great Texas Dynamite Chase. Although it was not my first feature film as an editor, it was his first film as a director. Since then, we have collaborated on various projects, which have given me the opportunity to watch him develop his craft and grow. I have learned a great deal about the editing process from him. Aside from directing films, he has wisely spent a great deal of time directing theatre productions. I feel that his work in the theatre has allowed him to gain a greater understanding of staging and blocking, as well as an expertise in working with actors. His background in theatre has broadened him, enabling him to get more textured and full performances as well as more interesting visual shots. When I look at dailies, I can frequently tell when the director has had theatrical training. Whenever I talk to young people getting started, I always encourage them to get involved in local theatre so that they can gain skill in staging and blocking, as well as working with actors.

Millie is very discerning with her craft:

The best editing is invisible. You should walk away from seeing a picture without being aware of the cuts that were made, unless they were made for a specific effect.

For the most part, I do not believe in using multiple editors. It's a very rare case that you don't feel the difference of each editor's sense of timing. I mean, what is editing, but an inner sense of timing—setting the pace of a film? In fact, one of the most important jobs of the picture editor is to control the tempo and the pace of the story. Through the cutting art of the picture editor, sequences can be sped up or slowed down, performances can be vastly improved, intent and inflections of dialog radically redesigned, giving an entirely new slant on a scene and how it plays out. When you keep switching from one editor to another through the course of the film, it lacks synchronic integrity. Even if you don't see it, you will feel a difference. It takes a rare director to herd over a project that utilizes multiple picture editors and end up with a fluid and seamless effort.

Whenever I had to have a second picture editor on the team, I always tried to have the choice of that editor. Very simply, I wanted that editor to have a pace and timing as close to my own as possible—so the picture would not suffer. Most often, I turned my own picture assistants, whom I had trained to have a taste and feel for the cutting to be similar to my own, into the second picture editor.

Millie has cut several projects on an Avid, but she does not allow the technology to dominate her. “Nonlinear editing is just another tool, but God bless it when cutting battle scenes, action sequences, or scenes with visual special effects. For me, this is where the nonlinear technology makes a substantial contribution.”

Millie has altogether different feelings if she is working on a project that does not require special visual effects:

I don't need all the electronic bells and whistles if I am working on a character-driven film. It is much more satisfying, and frankly, you will be surprised to learn, a lot cheaper. Once all of the collateral costs are shaken out of the money tree, working on film with either a Moviola or a KEM is more cost-effective. Additionally, you will discover that you are not as restrained by screening venues as when you are working in digital.

I miss the Moviola. Cutting on an Avid is much easier physically, but it is much quicker to become brain-dead. Working on the Moviola is a kinesthetic experience— the brain and body working together, preventing dullness and brain fatigue. I could work many more hours on the Moviola than I can on an Avid, and stay in better physical shape as well. Working on a digital machine, there is too much interference between you and the film—it fractures and dissipates your concentration. The wonderful thing about the Moviola is that there is absolutely nothing between you and film. You touch it, you handle it, you place the film into the picture head gate and snap it shut, and you are off and running.

To me, editing is as much a visceral as it is a mental act. Consequently, I love being able to touch film and have it running through my fingers as it goes through the Moviola. Even though working directly on film has a number of drawbacks, such as the noise of a Moviola, broken sprocket holes, splices, and much more, working on a keyboard gives one very little of the tactile experience of film. The young people today who are becoming editors have been deprived of this experience, and I think that it is very sad.

Young editors today are not learning to develop a visual memory. When you cut on film, you sit and you look and you look and you look. You memorize the film. You figure out in your head where you are going, because you do not want to go back and tear those first splices apart and do them over. On film, you know why you put the pieces of film together the way that you did. You've spent time thinking about it. While you were doing other chores or running down a KEM roll to review and out-take, your subconscious was massaging your visual memory through the process—problem solving. On a computer, you can start hacking away at anything that you want to throw together. If it doesn't look good, so what—you hit another button and start over. There is no motivation to develop visual memory.

The use of visual memory is critical, for both picture editor and sound editor.

There is as much to do in sound as in picture editing. At a running, someone might say, “Oh, Millie, that shot is too long,” and I would answer, “No, wait. Sound is going to fill that in.” Love scenes that seem to drag on forever in a progress screening, play totally differently when the music is added. When I cut the sequence, I can hear music in my head, so I cut the rhythm and the pace of the love scene against that.

Young editors are not developing this ability because it is too easy to put in an audio CD and transfer temp music cues into the computer to cut against. This works when they have CDs on hand, but what about if they need to cut a sequence without them? Ask them to cut film on a KEM or a Moviola in the change room of a dubbing stage, and watch the panic set in! The training is just not there. Some new editors panic if they don't have a time code reference to which they can pin their work.

Master picture editors will tell you that if you want to learn how to construct a film, watch it without sound. Sound tricks you—it carries you and points you, unawares, in many directions. By the same token, for many films if you only listen to the soundtrack you do not have the director's entire vision. The visual image and the audio track are organically and chemically bound together.

Sound effects and music are as important a voice in films as the spoken dialog; the audience uses them to define the characters’ physical being and action. Sound effects go right in at the audience; they bypass the dialog track in that they are proverbial—like music, they hit you right where you live. They also are extremely powerful in the storytelling process. In the performance of a single note, music sets the tone for what you are about to see and probably how you are about to feel. Good picture editors know this, and, as they sculpt and shape the pace and tempo of the film, they keep the power of the coming soundtrack well in mind.

HOWARD SMITH, A.C.E.

Howard Smith, A.C.E., veteran picture editor of both big-action and character-driven pictures (Snakes on a Plane, City of Ghosts, The Weight of Water, The Abyss, Near Dark, Dante's Peak, Twilight Zone: The Motion Picture), made the transition from cutting picture on film with a Moviola and a KEM to cutting nonlinear via the Avid:

As the picture editor, my primary task is to work with the director to try to shape the material so that it is the most expressive of what the film is intended to be. You try to tell a story, and tell that story as effectively as it can be told.

Figure 7.7 Howard Smith, A.C.E., picture editor.

It has been said that the editing process is essentially the last scripting of the movie. It's been scripted by a writer, the project goes into production, where it is written as images, and then it goes into the editing process—we do the final shaping. Obviously, we are trying to achieve the intent of the original written piece. Things will and do happen in production through performance, through art direction, through camera—that happen through stylistic elements that can nudge the storytelling a little that way, or this way. One has to be very responsive and sensitive to the material—I think that is the first line that an editor works at.

They look at the dailies, preferably with the director so the director can convey any input as to his intentions of the material. There may be variations in performance, and without the input from the director it will be more difficult to know his or her intentions versus happenstance, in terms of the choice of performance.

Early takes of a scene may be very straight and dramatic. As the filming continues, it may loosen up—variations could bring countless approaches to how you may cut the sequence. Which way does the editor take it? The material will give all kinds of paths that the editor can follow.

Years ago, there was a movement for editors to go on location, to be near the director and crew during production. This can often be a good thing, as a good editor can lend guidance and assistance in continuity and coverage to the shoot.

As we have moved into electronic editing and the ability to send footage and video transfers overnight via air couriers or even interlocking digital telephonic feeds, the pressure for editors to be on location with the director has lessened. Personally, I do not think that this is necessarily better. At the very least, we lose something when we do not have that daily interaction as the director and editor do when they share the process of reviewing the dailies together.

During production, the editor is cutting together the picture based on the intention of the script, and the intention as expressed by the director. By the time the production has wrapped, within a week or two the editor has put together the first cut of the movie.

The director has traditionally gotten some rest and recuperation during those first couple of weeks before he returns to the editing process. For approximately 10 weeks, as per the DGA contract, the director and editor work together to put the film together in its best light for the director's cut.

What editing will do is focus—moment to moment, the most telling aspects of the scene. When you do this shaping, it is such an exciting experience, the mixing of creative chemistry. Most directors find that the most exciting and often satisfying process of the filmmaking experience is the film editing process. It is during these critical weeks that everything really comes to life. Sure, it is alive on the page of the script, it is alive on the set during principal photography, but when you are cutting the picture together, the film takes an elevated step that transcends all the processes up until that point—it really becomes a movie.

Obviously the addition of sound effects and music, which will come later after we have locked the picture, will greatly elevate the creative impact of the film, taking it to new heights—but that is only to take the film to a higher level from a known quantity that we have achieved through picture editorial. Great sound will make the movie appear to look better and be more visually exciting; a great music score will sweep the audience into the emotional directions that the director hopes to achieve, but the greatest soundtrack in the world is not going to save or camouflage bad picture cuts.

With the advent of nonlinear technology we are now able to add in temp music and sound effects in a far more complex way than we ever could with a Moviola or KEM, we are able to work with sound and music even as we are cutting the picture—as we go along. We now see editors spending more time, themselves, dealing with those elements. I don't know if that is a bad thing, especially if you have the time to do it.

I remember when I was working on The Abyss. We were not working digitally yet. There were many, many action sequences. Jim [Cameron, the director] expressed to me that you can't really know if the cut is working until the sound effects are in. I thought that was very interesting. It was the first time that that way of thinking had ever been put to me— and you know Jim and sound!

On a visual level, if you are working on a big special effects picture with a lot of visual effects, and they are not finished, what have we always done? We used to put in a partially finished version along with one or more slugs of SCENE MISSING to show that there is a missing shot, or we shoot the storyboard panels that represent the shots.

Before, when I cut an action piece, I always cut it anticipating what I know the sound designers could do with the action. I have a car chase sequence, and the vehicles are roaring by the camera. I will hold a beat after the last car has passed by, giving sound effects time to pan a big “whoosh” off-screen and into the surround speakers. If I do not give that beat, the editor is not going to have the moment to play out the whoosh-by sound effect, and the re-recording mixer is not going to be able to pan the whoosh off-screen and into the surround speakers.

That was part of my editing construct, based on my editing experience previously. It would leave a little bit of air for the composer, knowing that music would have to make a comment, and music needs a few seconds to do that, and then sound effects would take over.

I remember Jerry Goldsmith [film composer] saying, “They always want me to write music for the car chase, and I know that you are not going to be able to hear it—but I write it anyway.” We know that even if the sound effects are very loud, if you did not have the music there, you would feel its absence. The emotional drive is gone. Through experience, these are things that you learn over a period of years.

Because of the Avid and the Final Cut Pro, I am now cutting sound effects into the sequences almost as soon as I make my visual cuts. I layer in visual type sounds, temp music, etc. Now, when I am playing the newly cut sequence for the director for the first time, I have a rich tapestry of picture and audio for him to evaluate, rather than the way we did it before nonlinear days. When we would watch the cut sequence with only a production track and mentally factor in sounds to come, sounds that definitely have an effect and influence on the pace—the rhythm and the voice of the scene. This tells the director if the film is working on an emotional level. It adds this emotional component immediately, so you can feel the effectiveness of the sequence, in terms of the storytelling overall.

These sounds are not cut in to be used as final pieces. Do not misunderstand. I am not doing the sound editor's job, nor do I pretend to be able to, nor do I want to. I know full well that when we turn the picture over to sound editorial, my sound effects and temp music are going to be used only as a guide for intent, then they will be stripped out and replaced by better material.

Working with Cameron was a real concept for me. He would bark, “Let's get some sound effects in here right now! Let's see if this scene is kicking butt—right now!” So we would.

Figure 7.8 Joe Shugart, picture editor.

This puts the supervising sound editor and his or her sound designer to work problem solving these questions and needs early on. Traditional scheduling and budgeting fail dismally to fulfill the Camerons of the filmmaking industry (who already understand this audio equation to picture editing) and an ever-growing number of filmmakers inspired and empowered by understanding what is possible. Trying to function with outdated budget philosophies and time schedules is sure to make future cinematic achievements even more rare.

A SERIES OF BREAKS

Picture editor, and future director, Joe Shugart contributed the following reflections:

During my 18-year career in film and television editing, I've often been asked by assistants, friends and family how I got to where I am now. I usually throw out something funny like “You mean how did I get to the middle?”

Living in Los Angeles can make you jaded. You always hear about the overnight sensation. Actors, artists, and producers all can be heard saying, “If I could just catch a break, my career would explode.” But that's not how breaks usually happen. Breaks in the film business are small and often imperceptible, and it takes a lot of them.

My first break came in the late spring of 1988. Having finished film school, I was a producer/director currently working as a waiter. I heard about an action movie called Cyborg which was coming to film in my home state of North Carolina. Since they already had a producer and director, I decided to go for a more realistic job, apprentice editor. I somehow talked the production coordinator into giving me the address of the film editor and so I sent her a copy of my student film with a letter explaining that I was a hard worker and would like to be considered for the position of apprentice editor.

She called me and asked if I would work for free for the summer. Now unless waiting tables has blossomed into some lucrative high-paying job I'm not aware of, you can understand my nervousness over embarking into the movie business—could it actually pay less than waiting tables? Yes, it can. Despite a molehill of savings, I decided to go for it.

The days were long, filled with marking the sound and picture, syncing the dailies, coding the edges of the film and track with numbers so they could always be matched up, and logging everything into a book since they didn't furnish a computer. The director and editor were fantastic to work for, and they allowed me to watch the dailies projected every day, a real thrill which is unfortunately not done so often now, especially on the small films.

The job was going well, and after eight weeks of filming the crew was ready to wrap and move back to Los Angeles, where editing would resume. I was talking with the picture editor one day near the end and asked her if they would be hiring someone in Los Angeles to replace me. She said yes. “Can I replace me?” I joked.

She told me if I wanted to stay on they would love to have me. The icing on the cake came the next day when she told me that they would pay me $350 a week. That's a six-day week, usually from 9 a.m. to about 9 p.m. The math worked out to about $5 an hour, not including overtime, since they wouldn't be including any of that either. I took it in a heartbeat and made a temporary move to Los Angeles for three more months of postproduction.

Cyborg opened to moderate success, but when it was done, the phone was not ringing with calls from agents and producers with high-paying offers, so I returned home and got a job while I tried to catch that next break. The break came in the form of a call from the first assistant editor of Cyborg, the guy who had been in charge of running the editing room and teaching me all those skills. He was getting a chance to move up and cut a small horror movie. He said he needed a first assistant and he thought I was the one for the job. That was all I needed to hear. I packed up my old VW with what it could hold and made the four-day journey west.

The job as the first assistant was much more demanding. It not only included the syncing, logging and coding of dailies, but lots of work lining up optical and visual effects. Let's say a creature has to explode in a burst of light. Well, the point where this effect must occur is translated to the visual FX creators by referencing the film's key number, or edge number, where the burst must start and end. The sheets used to convey this information are called “count sheets,” and it takes careful notation to ensure accuracy. If the director wants to reverse the motion of the film, speed it up or slow it down—those too are optical effects and must have a new piece of film negative generated so the shot can appear in the film (this is not necessary for films which are finished on video or hi-definition). All of this work—and more fell under my domain.

Anyway, that was a tough job and the movie ended up going to that great video store in the sky without a release. But it led to the next break, working on Jacob's Ladder—a great film where my skills in visual effects were severely tested. That break led to the next, and the next after that. Within a few years I was given the chance to cut a scene or two alongside the first-assistant-turned-editor from the horror movie.

Then I began co-editing episodes of Zalman King's Red Shoe Diaries. Zalman liked my work and enjoyed my company so much he gave me a chance to cut my first half-hour episode on my own. This time it wasn't going to be on film—this time it was cut on the Avid system. I ended up editing or co-editing 16 of these episodes, which led to getting my first feature. They loved my work, so that led to more.

Nine small features and countless episodes of television later, I found myself needing another break. This was in 2002. The independent film market had severely dried up, and there was worry throughout the industry of a possible actors strike. The small budget films simply were not paying much of a salary to editors (they still aren't) and the big films were impossible to get. After years of being a full-fledged editor, I was stuck and went back to work as an assistant editor. It was heartbreaking.

A shift in programming was occurring then with this relatively new thing called “reality” television. My dramatic editing background looked good to producers of these shows and another break occurred when I was hired to co-edit the first “reality feature” by the makers of The Real World. This film was called The Real Cancun, and though it was not well received, I was.

The company, Bunim-Murray Productions, loved me and continued to hire me. This relationship led me to receiving the daytime Emmy award in 2006 for single camera editing on their show called Starting Over. Its title carries profound implications into my career. This business has a way of changing the rules as soon as you get comfortable.

Along the way, I wrote and directed my first half-hour 35-mm film, Bad to Worse— which the author of this book, David Yewdall, so graciously agreed to design and cut the dialog and sound effects for. He worked for free, as I had done so many years ago, because he loves the creative process. I can never repay him for the countless hours and creative genius he brought to my film. I will be forever in his debt.

The film went on to show at two film festivals, the Los Angeles International Short Film Festival and the Marco Island Film Festival. I hope someday to direct a feature, if I can only catch a break, or maybe a series of them.

TOUCH IT—LIVE IT

Leander Sales helms the picture editorial discipline at the North Carolina School of the Arts-School of Filmmaking. Leander knows the vital importance of the synchronizer and flat-bed editing machines.

If you are going to be in film school, then touch film. Get to know film and the whole process. If you can get a chance to cut on a Steenbeck, you will get a true sense of history. If the kids would just work with the film on the flatbed, I think they would understand the history of film a lot better, because they are living it. Of course, that's where I came from, I learned cutting on film, but now everybody is cutting on the Avid or the Final Cut Pro, including me. I appreciate those formats as well. When I used to work on film, it is amazing how you can manipulate it, how you can look at every frame, just hold it up to the light and you can look at every frame. We are living in a digital world and will never go back to cutting on film, but I still think people should understand that history.

I remember working with an editor by the name of Sam Pollard. He would just hold the film up and looking at where he made his marks and how he made his cuts and, wow—you look at it and it is like life is just frozen in that frame. Now you run them all together through the machine, at twenty-four frames a second, and you create something new.

I remember the first scene I was cutting. Sam Pollard [picture editor] gave me an opportunity to cut a scene in Clockers. He gave me the footage and he said, “Here it is, go cut it.”

That was it—go cut it. I remember it was the scene of the guys crushing up the car, pretty much two-camera coverage with all these jump cuts in it. And I was like, wow, this is my first scene. It was so exciting to put it together and at the end of the day, have Sam come up and look at it and say, “Okay.”

Then another scene came and another scene came. So, I was very happy to finally get a credit as an editor.

What's interesting is that Sam doesn't like assistants who are working with him who do not want to cut, because the next growth step should be to cut. As an assistant you should want to move up to be an editor. I feel the same way. When I hire somebody as an apprentice, your desire should be to move up to be an assistant, and then to editor. And if your heart isn't there, I'm thinking that I could have hired somebody whose heart would be—who would really have a strong hunger to edit—not someone who just wants to hang out in the editing room—but someone who wants to do it. It's really important to have that hunger, because once you have that hunger, nothing else can stop you, nothing! And with the accessibility of editing equipment right now with Final Cut Pro, there is absolutely no excuse. Go and get a little mini-DV camera and shoot—there is no reason why you shouldn't be making a film—especially if you want to do it.

FINDING A WAY TO BREAK INTO AN EDITING JOB