Chapter 9

Spotting the Picture for Sound and Music

“The studio jet is waiting for me, so we're gonna have to

run through the picture changes as we spot the music, the

dialog, and sound effects all at once—okay?”

– Steven Spielberg, announcing his combined spotting-session

intentions as he sat down behind the flatbed machine

to run his segment of Twilight Zone: The Motion Picture

Spotting sessions are extremely important in the ongoing quest to produce the requisite desired final soundtrack. They present an opportunity for the director to mind-meld with the music composer and the supervising sound editor(s) on the desired style and scope of work in a precise sequence-by-sequence, often cue-by-cue, discussion. The various functions (music, sound effects, and dialog/ADR) have their own separate spotting sessions with the director, allowing concentration on each process without thinking of or dealing with all other processes at the same time.

During this time, the music composer and supervising sound editor(s) run through reels in a leisurely and thoughtful manner, discussing each music cue, each sound effect concept, each line of dialog and ADR possibility. This is when the director clearly articulates his or her vision and desires, at least theoretically. Very often, the vision and desires concepts are very different from the style and scope-of-work concepts—these often are completely different from each other from the start and probably will be so even at the final outcome—for practical or political reasons.

The spotting process also is an opportunity for the music composer and supervising sound editor(s) to share thoughts and ideas collaboratively, so their separate contributions to the soundtrack blend together as one, keeping conflict and acoustic disharmony to a minimum. Sadly, the truth is that often very little meaningful collaboration occurs between the music and sound editorial departments. This lack of communication is due to a number of unreasonable excuses, not the least of which is the continuing practice of compressing postproduction schedules to a point that music and sound editorial do not have time to share ideas and collaborate even if desired. (I briefly discuss the swift political waters of competition between sound effects and music in Chapter 19.)

SIZING UP THE PRODUCTION TRACK

Before the spotting session, the condition of the production dialog track must be determined. To make any warranties on the work's scope and budgetary ramifications, the supervising sound editor must first screen the picture, even if it is only a rough assemblage of sequences. This way, the supervisor obtains a better feel for both audio content and picture editorial style, which will definitely impact how much and what type of labor the dialog editors need to devote to re-cutting and smoothing the dialog tracks. Reading the script does not provide this kind of assessment. The audio mine field is not revealed in written pages; only by listening to the raw and naked production track itself through the theatrical speaker system will the supervisor be able to identify potential problems and areas of concern.

Two vital thoughts on production track assessment are as follows: first, clients almost always want you to hear a “temp-mixed” track, especially with today's nonlinear technologies. Picture editors and directors do not even give it a passing thought. They use multitrack layering as part of their creative presentation for both producers and studio, but it does not do a lick of good to try to assess the true nature of their production dialog tracks by listening to a composite “temp mix.” Clients usually do not understand this. They often want to show you their “work of art” as they intend it, not as you need to listen to it.

This is likely to lead to unhappy producers who complain when you return their work-in-progress tape or QuickTime video output file, to supply a new transfer with nothing but the raw production dialog, which means that they have just wasted money and time having the videotape or QuickTime video output made for you in the first place. However, if you had supplied them with a “spec sheet” (precise specifications), they would not have made the video output the way they did, and you would not be rejecting them now and insisting on a new transfer. Or, if they still supplied you with an improperly transferred video output, you have a paper trail they was ignored, taking you off the hook as a “trouble maker” because they did not read the spec sheet in the first place.

Second, to assess the quality of raw production track properly, listen to it in a venue that best replicates the way it will sound on the re-recording stage. This dispels any unwanted surprises when you get on the re-recording dub stage and hear things you never heard before. The picture editor, director, and producers are always shocked and amazed at what they never heard in their audio track before.

Never try to assess track quality on a Moviola, on a flatbed editing machine (such as a KEM or Steinbeck), or even on a nonlinear picture editorial system such as an Avid or Final Cut Pro. All picture editorial systems are built for picture editors to play tracks as a guide for audio content. I have never found a picture editorial system that faithfully replicates the soundtrack. Many times picture editors must use equipment on which the speaker had been abused by overloading to the point that the speaker cone was warped or damaged. Few picture editors set the volume and equalization settings properly, so track analysis is very difficult, with very few picture editors setting up their systems to reproduce the soundtrack with a true “flat” response.

For these reasons, I always insist on listening to the cut production track on a rerecording stage, and, if the sound facility has been selected by this time, I want to run the picture on the very re-recording stage with the head mixer who will be handling the mixing chores. This is the best way to reveal all warts and shortcomings of the production track. You will then know what you are dealing with, what your head mixer can do with the material, and how it can be most effectively prepared for the re-recording process (see Chapters 12 and 13).

The screening also gives the director and producer(s), along with the picture editor(s), an opportunity to hear the actual, and often crude, condition of their production track—transparent to the ears through the theatrical speaker system without the benefit of audio camouflage that temp music and temp sound effects often render. I guarantee you that you will hear sounds you have never heard before, usually unpleasant ones.

TEMP MUSIC AND TEMP SOUND EFFECTS FIRST

The picture editorial department must understand the necessity of going back through its cut soundtrack and removing any “mixed” track (where the dialog track has been temp-mixed with either music and/or sound effects), replacing it with the original raw sync dialog track; hearing the dialog with mixed music or sound effects negates any ability to properly evaluate it.

The smart picture editor who cuts on a nonlinear platform will do himself or herself a great favor by keeping any temp sound effects, temp crash-downs, temp music, or any other non-pure production sound cues on separate audio channels. The first two or three audio channels should be devoted to production dialog only. Any re-voicing, added wild lines, even WT (production wild track) must be kept in the next group of channels. In this way the picture editor will have a very easy time of muting anything and everything that is not production sound. I have had to sit and wait for over an hour while a rookie picture editor, faced with the fact that we are not there to listen to his total cut vision, has to take time to go in and first find and mute each cue at a time because he or she has them all mixed together without disciplined track assignments.

The dialog mixer is the one who mixes it, the one who fixes it, to create the seamless track you desire; this is your opportunity to get the mixer's thoughts and comments on what he or she can and cannot fix. The mixer runs the worktrack through the very console that ultimately will be used to accomplish the dialog predubbing. During this run, the mixer determines what he or she can accomplish, often pausing and making equalization or filtering tests on problematic areas, thereby making an instant decision and warranty on what dialog lines most likely will be saved or manipulated. What dialog cannot be saved obviously must be fixed, using alternate takes and/or cueing material for ADR. If temp music and temp sound effects are still left in the cut production track (as a mixed combine), your head mixer cannot discern what is production and what is an additive.

AFTER THE “RUNNING”

You had your interlock running with your head mixer on the re-recording stage—and had to call the paramedics to revive the clients after they discovered their production track was not in the clean and pristine shape they had always thought. The preliminary comments stating that the production track was in such good shape and that only a handful of ADR lines were anticipated fell apart in the reality run-through, which yielded a plethora of notes for ADR. Suddenly, you cue this line and that line for reasons ranging from airplane noise to microphone diaphragm popping, from distortion, off-miked perspectives to off-screen crew voices. The next step is for everybody to go home, take two Alka-Seltzers, and reconvene in the morning to address the issues afresh.

The supervising sound editor is wise to bifurcate the upcoming spotting session. Clients often try to make one spotting session cover all needs. Unfortunately, as one facet of the sound requirements is being discussed, other audio problems and considerations tend to be shut out.

It is much smarter to set up a spotting session where the supervising sound editor(s) and both the dialog editor and the ADR supervisor sit with the director, producer(s), and picture editor to do nothing but focus on and address the dialog, ADR, and Group Walla needs. The supervising sound editor(s), along with the sound designer, then schedule a spotting session specifically to talk about and spot the picture for sound effects and backgrounds. The supervising sound editor(s) may have one or more of his or her sound effects editors sit in on these spotting sessions as well, for nothing is better or clearer than hearing the director personally articulate his or her vision and expectations as you scroll through the picture.

CRITICAL NEED FOR PRECISE NOTES: A LEGAL PAPER TRAIL

During a spotting session, both the supervising sound editor(s) as well as the attending department heads take copious notes. If the sound editorial team does not understand something, they must pause and thoroughly discuss it. It is very dangerous just to gloss over concepts, assuming you know what the director wants or intends. If you assume incorrectly, you waste many valuable hours of development and preparation that yield worthless efforts. In addition, you lose irretrievably precious time, which certainly erodes the confidence level of the clients.

As obvious and apparently simple as this advice is, the failure to take and keep proper spotting notes can cause calamitous collisions later. On many occasions, a producer relied on either my own notes or the notes of one of my department heads to rectify an argument or misconception that simmered and suddenly boiled over. Consequently, your spotting notes also act as a paper trail and can protect you in court should the rare occasion of legal action arise. Remember, sound creation is not an exact industry. It is an art form, not a manufacturing assembly line. Boundaries of interpretation can run very wide, leading you into potentially dangerous and libelous territory if you have not kept accurate and precise spotting notes. The purpose is to accurately map and follow the wishes of the director and producer, and to achieve the same outcome and creative desires.

Some supervising sound editor(s) go so far as to place an audiocassette recorder or small DAT recorder with an omnidirectional mike in plain view to record the spotting proceedings; the tape then can be reviewed to ascertain the precise words of the director or producer when they articulated their creative desires and asked for specifics.

THE SUPERVISOR's BIBLE

Because spotting sessions often move at a rate considerably faster than most people can push a pencil, most of us resort to a series of shorthand-like abbreviations or hieroglyphics to jog our memories later. Therefore, you must take time soon after the spotting session to go back through your notes and type a much more formal narrative with appropriate footnotes and directions for others going through the sound editorial adventure with you. Using a personal computer notebook in a spotting session is not a good idea. You cannot write or manipulate where you want the information on the document quickly enough. Write your notes by hand during the spotting session, then transcribe them to your computer later.

The supervising sound editor dedicates a binder (sometimes more than one) to amass the steady flow of notes, logs, EDLs, schedules and all revisions, and copies of faxes and memos from the producer's office, from the director as well as the picture editor. In short, this binder contains all the pertinent data and paper trail backups that guide the development of the soundtrack to successful fruition and protect you from future misunderstanding.

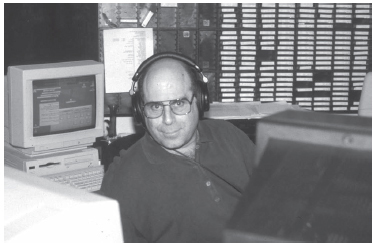

Figure 9.1 Supervising sound editor George Simpson reviews sound effect cues as he builds his “cut-list bible,” having handled such projects 16 Blocks, Freedomland, The Ring Two, Paparazzi, Tears of the Sun, and Training Day to name a few. (Photo by David Yewdall.)

As a result of all the care taken, you will develop an awareness and observational focus that is extremely important in the spotting session process. You will notice that which the picture editor and director have not seen, and they have lived with their film for months, in some cases even a year or more before you have been called in to “spot” the picture with them. One such case occurred during a sequence where the actor came to his car, opened the door, got in, and closed the door. I put my hand up for a question. The editor stopped the film. I asked on which side of the cut did they want the door to close. The editor and director looked at me like I had just passed wind at the dinner table. “When the door closes, you match the door close. What could be easier?” asked the picture editor. I pointed out that as the actor got into the car, the door closed on the outside cut, and, when they cut inside the car with the actor, the door closed again. “The hell you say,” replied the editor.

I asked them to run the sequence again, only very slowly so we could study the cut. Sure enough, actor David Carradine got into the car and the door just closed; as the angle cut to the inside, you clearly could see the door close again. The editor, who had been working on the picture for just over a solid year, sighed and grabbed his grease pencil to make a change mark. All this time he, the director, and the producer had never seen the double door close.

SPOTTING SESSION PROTOCOL

Very early on, one learns that often insecure sensitivity in the first spotting session requires certain delicacy when discussing problematic topics thereafter. On one of my earlier pictures, I spotted the picture with a picture editor I had known for a number of years, dating back to Corman days. I had not worked with the director before; in fact it was his first feature directing job. We finished running through a particular scene where actor Donald Pleasance was discussing a crime scene with a woman. I commented to the picture editor that the actress could not act her way out of a paper bag. The picture editor's brow furrowed as he gave me a disapproving glance. At the end of the reel, the director, noticeably fatigued, left the room for a smoke break. The picture editor grabbed the next reel off the rack, leaned over, and informed me that the actress was the director's wife. After that colossal faux pas, I learned to research diligently who was who in the production team and in front of the camera.

Other sensitive situations can arise when you have a tendency to count things and are spotting the film with a picture editor who thinks his or her work is beyond reproach. Such was the case when we held our spotting session on the sci-fi horror film The Thing. I brought my core team with me, as was my custom. I had already handled two pictures for John Carpenter, so I was not concerned about unfamiliar ground. I knew he was very comfortable and secure with himself.

The problem arose because I tend to count things, almost subconsciously. I developed this habit while supervising soundtracks and having to think on my feet during spotting sessions. In the case in question, a scene in the film depicted Kurt Russell checking out the helicopter outside when he hears a gunshot from within a nearby laboratory building. He jumps off the chopper and runs into the building and down the hallway, hearing more pistol shots. He reaches the lab, where Wilford Brimley was warning the rest of the staff to stay away. In a matter of moments, the team outmaneuvers and subdues the scientist after he empties the last two bullets from his pistol.

Once again, I raised my hand with a question. The picture editor paused the film.

I glanced around to my team members and then to the director. “Do you really want us to cut eight gunshots?” I was taken aback by the picture editor's response. “You can't count! There are only six gun shots!”

I was willing to let it go. I knew full well that the editor had only meant to have six, so I would just drop two from the guide track. But John Carpenter loved to have fun. He grinned like a Cheshire cat at the opportunity. “Let's go back and count ‘em.”

The picture editor spun the reel back to the exterior with the helicopter. He rolled the film. The first off-stage gunshot sounded, and everyone counted. “One.” Kurt jumped off the chopper skid and dashed into the building, past boxes of supplies as another shot rang out. “Two.” Kurt reached the doorway to the lab. He was warned that Brimley had a gun. Wilford turned from swinging his axe at the communication equipment and fired a warning shot at Kurt. “Three.” Kurt told the guy next to him to maneuver around to the doorway of the map room. As the other actor reached the doorway, the crazed scientist fired another warning shot at him. “Four.” The actor ducked back as the bullet ricocheted off the door frame. The scientist stepped into the center of the room as he fired two more on-screen shots. The image cut to the door frame, where we saw three bullets hit and ricochet away. Everyone counted. “Six and … .” Nobody dared continue counting. The picture editor stopped the film and growled at me. “So you'll cut two of them out.”

As it turned out, we could only drop the one as the hero was running down the hallway because it was off-stage. The way the picture editor had cut the sequence as Brimley emptied his pistol, we couldn't trim any additional pistol shots without the picture editor first making a fix in the picture, which he was unwilling to do.

WHAT REVELATIONS MAY COME

Other, more costly ramifications, constructive or not, certainly can come out of a spotting session. I was spotting the sound requirements on a superhero-type action picture when the director and I reached the point in the film of a climactic hand-to-hand battle confrontation between the hero and the mobster villain. At the very point where the villain literally had the upper hand and was about to vanquish his vigilante nemesis, a door at the back of the room opened. The mobster villain's young son entered to see his father in mortal combat at the same time the villain turned to see his son. Taking full advantage of the distraction, the hero plunged his huge bowie knife into the villain's back.

The director noticed my reaction and stopped the film, asking me what the matter was. I politely apologized: I guess I missed something somewhere in the picture, but who was the hero? The director was shocked at my apparent lack of attentiveness. If I had been paying attention I would have known that the whole picture revolved around this guy on the floor, our superhero, and how he was taking revenge against the forces of the underworld for the loss of his family.

Yes, I did notice that. I also pointed out that in a blink of the eye the director had changed the hero from a sympathetic hero to a moralistically despicable villain. Not only had he stabbed the mobster villain in the back, but he performed this cowardly act in front of the villain's son.

A steel curtain of realization dropped on the director. This elementary rule of storytelling had just blown its tires while hurtling down the highway of filmmaking. The director told me to commence work only on the first nine reels of the picture, as he was going to meet with studio executives to decide what to do about the ending.

A few weeks later, the set, which had been torn down in Australia, was being rebuilt in Culver City, California (where they shot Gone with the Wind) precisely as it had been in Australia, precisely. Frames from the master angle of the film were used to meticulously replace broken shards of glass that lay on the floor so that the two filmed segments would match. Actors were recalled from all over the world. Lou Gossett, who played the police lieutenant, had crossed through the carnage at the end of the action sequence when it was first shot in Australia, was not available, so the director had to employ the industry's top rotoscope artist to painstakingly rotoscope a moving dolly shot to carefully mask out the telltale knife protruding from the mobster's back from the original Australian shoot footage that had Lou Gossett crossing through.

Other audio challenges resulted from the re-shoot when we discovered that the boy portraying the mobster's son had grown since the original shoot, and his voice was changing. This meant pitch-shifting the boy's dialog tracks upward by degrees until we could accurately match the pitch and timbre of the original material shot months before in Australia.

The observant problem-solving approach to spotting sessions is invaluable. Learn to glance at a building, then turn away. Now ask yourself how many floors comprise the construction of the building. How many windows are in a row on each floor? Are they tinted or clear? Develop your observation skills to accurately recall and describe what you see, and it will serve you extremely well.

Also learn to listen to what people say. People often repeat what they thought someone said, or their own perception of what they said, but not what was actually said. These kinds of skills stem from dialog editing and transcribing muffled or garbled words from a guide track to cue for ADR. You do not transcribe the gist of what they said, or an interpretation—you must write down precisely what they said. Even if you intend to change the line later in ADR, you first must know exactly where you are before you can continue forward.