Chapter 16

ADR and Looping

Getting the Lips to Flap in Sync

“The actors were whispering … whenever they weren't yelling.”

– Jeffrey Haupt

I believe in the magic of the production track. If the director and producer want less ADR in their films and more of that magic production, then they must work more closely with the production mixer. They must put a lot more effort and patience into getting the magic of the production track at the time of principal photography, or they ultimately pay extra budget dollars and time to revoice the actors later on the ADR stage. All right, best effort or not in trying to capture a great production track, the fact is, here you are with a certain amount of need for revoicing dialog.

Before we proceed, the first thing we need to do is clarify the difference between ADR and looping. Today we so often use the term loop or looping when we talk about an ADR session. We say, “We need to loop these lines” or “She does not loop well,” when we are really referring to the process of vocal replacement and not the actual technique itself.

The technique of looping goes back to the beginnings of motion picture sound. In order to re-perform dialog over an existing visual performance, a “looping editor” would have to roll both picture and optical track through a synchronizer, listening for the lines using the optical head mounted over the second gang of the sync block. Once the editor found the line to be looped, he or she would cut both picture and track out, precisely in sync, making a mark with a grease pencil of the matching frame lines. The editor would add a little extra on either side of the line so that the actor would have a lead-in. Both picture and sound were then spliced head-to-tail, making a film loop, with the start frame clearly marked and punched in the center.

The loop editor would then take a grease pencil and make an angular one-foot-long cue on the picture. This was a visual reference for the actor to see when the first frame of modulation of the line to be re-performed actually started.

The punched hole in the film was to assist the projectionist when he or she would slide the looped picture into the gate of the projector. It was often extremely difficult in the dim light of the projection booth to see the grease pencil marks once the film was inside the gate area, but there was no mistaking the bright illumination coming through the punched hole, even when the douser of the projector was closed.

Once the picture film loop was loaded into the projector and the audio film loop was loaded into an optical playback dummy (term used for a play-only machine that slaves to other machines), the projector and playback dummy were put on the line (interlocked together by a distributor drive unit) so that when the projector ran forward, the playback dummy would run forward exactly in sync.

The looping mixer was given a green light and the mixer would tell the looping editor and actor on the stage that the next cue was ready. With that the mixer would roll the projector, which of course rolled the playback dummy. The cue to be re-performed would be seen on the screen, along with the grease pencil cue that would cross the screen (usually left to right), ending with the beginning of modulation of the line to be replaced. The original recording was also being heard as the actor would spend a few moments rehearsing it.

When the actor was confident that he or she was ready, the loop editor would tell the mixer that they were ready to make a take. The mixer would have the recordist put the optical film recorder on the line with the projector and playback dummy. Once the mixer rolled the projector and got up to speed, the actor would perform the line. The loop would continue to go around and around, allowing the actor to re-perform the line several times, sometimes giving variations and different reflections to the performance.

Once the actor and looping editor were satisfied, the mixer would stop the projector and the crew would take down the picture and audio loops and put up the next cue loops. This is the way it was done for many years. The basic difference being that in the early 1950s optical sound recording was replaced by 35-mm magnetic film recording.

Understand that there was no way to stop and back up and listen to these recordings. The projector, reproducer dummies, and recorder were incapable of operating in reverse, as we know today. What became known as rock-and-roll technology, which allowed projector and playback equipment to stop and reverse in sync, did not come into existence until the mid-1970s. As late as 1978 I worked on a picture that was mixing at the Warner Brothers sound department where we still could not stop and back up.

A variation of this style of looping was done at a few studios, such as Universal, who specialized in a heavy amount of looping, especially as they were handling vast numbers of television shows. These looping rooms used the same technique of using physical film loops, but with an important variation difference. At the end of each day's shoot two copies of the circled takes were transferred to 35-mm mag stripe by the sound department. These copies were made on two interlocked mag stripe recorders, making them simultaneously. The picture editorial apprentice would pick up one set and the show's loop editor would pick up the other set. The loop editor would break down all of the lines that each actor said, carefully making notes of scene/angle/take. Each actor's lines were then made into a loop, but a slightly different kind of loop. They did not bother with picture, which was too costly and took too much time for the process to run the cycle through the laboratory and back to sound editorial.

The loop editor would make each loop the length of the performance and again as long with two extra beats of fill. This would allow room for the actor to comfortably repeat the line during the blank period of the loop after he or she had just heard the original portion of the track played back in their headsets.

These loops were carefully marked with show code number, actor name, scene, angle, take, and then each actor's loops were placed in 2,000-foot film cans and stored on a rack. The following day, after the actor had completed that day's shoot, he or she would report to a looping room where the actors would re-loop all the lines that they had performed the day before. This gave incredible latitude to picture editorial and subsequently sound editorial during the sound editorial phase after picture lock, greatly speeding up the postproduction phase as they rarely had to call actors back in, except to change performances with different dialog than originally written.

These looping rooms did not project picture. The machine room loader threaded the loop onto a sprocketed 35-mm playback machine. As the loop played, it traveled around and around over the playback head, first playing the actor's original performance, then falling silent as the blank 35-mm fill passed over. This allowed the actor in the booth to repeat the line he or she just heard. As the loop continued around, the actor would hear the loop again and then, during the blank spot, would repeat the line, only this time altering the performance, giving a different inflection or emphasis. This process continued until the actor delivered 10 or 15 variations, enough from which the loop editor and director could choose.

Once the cue was finished, the machine room loader removed the first loop and loaded the next, continuing the same process through the listed cues. The recordist placed a hand written note of the next loop's code number on a piece of tape and placed the tape on the 35-mm mag stripe (after the record head) for ease in breaking down the recordings later by the loop editor assistant. Once ready the green light would come in, notifying the room that the loop was mounted and ready to roll. The looping mixer would roll the loop for the actor to listen to and get comfortable with. Once the actor signaled that he or she was ready, the recordist would place the 35-mm mag stripe film recorder on the line, interlocking it to the reproducer dummy.

The actor stood next to a music stand that held the looping editor's notes and printouts of the actor's lines. This gave the actor a tremendous advantage. The actor could close his or her eyes and concentrate on listening to the performance and then re-performing his or her performance, either as an exact match or with variations. It gave the actor the freedom to act, rather than be overwhelmed with having to watch picture, take notice of cue stripes or hear beeps in the headset, or try to match lip flapping to the visual. All of these non-acting demands distracted and pulled the actor out of the realm of delivering an audio performance.

That said, we will review this philosophy and present style of how to recapture this almost lost art form in the last part of this chapter.

This technique will also serve you well when it is extremely difficult to access actors who are literally unavailable to an ADR stage or looping room. You must be very creative in working with these actors, even when they are shooting a film in the jungles of Africa or Antarctica, definitely nowhere near an ADR stage until long after your postproduction schedule and the 2-track print master has already been delivered to the laboratory. I will discuss the mechanics of this location looping technique later in the chapter under “Remote Location Looping.”

ADR

In the mid-1970s, with the advent of the rock-and-roll system, where projectors, reproducers, and recorders could stop, reverse, and roll forward again in absolute sync, the system of ADR came into being.

Contrary to some beliefs, ADR does not stand for “All Dialog Is Ruined,” though some directors would certainly argue that with me. The initials ADR are quoted two ways: “Automatic Dialog Recording” and “Automatic Dialog Replacement.” Personally I do not understand why some refer to it as “Automatic Dialog Replacement” because it does not replace anything—it takes an ADR editor to do that. Where the term really stems from is the fact that for the first time an ADR mixer could program into the stage automation equipment a precise foot and frame that he or she wished the film recorder to record and what foot and frame the mixer wished the film recorder to cease recording.

Based on these numbers that were physically entered into the automation using analog pushbutton switches, the equipment would react to preset parameters to roll at high speed (in those days six times speed was high speed) down to the desired line, sense the proximity of the foot and frame and automatically slow down and park itself so many feet before the line. As computer programs started to drive the automation equipment, programming became even more complex and more detailed—entering a digital reality.

Time code was used when the video was on a magnetic tape medium and the video machine needed to be slaved in perfect sync with the rest of the equipment, and so ADR stages became automated set-ups so that the ADR mixer could choose whether to work and enter in and out cues in either feet and frames or in time code.

The mixer would roll back and forth through the line for the actor to get a sense of the performance. Precisely 3 feet before the foot and frame entered by the mixer, the automation triggered the ADR beeps (single-frame 1-kHz tone), so that the actor would hear three very short rhythmic beats just prior to the actual line to be replaced. These are known as the “beeps” (or “pips” to many English editors), spaced every 16 35-mm frames apart, equal to one beep every foot. Where the fourth beep would have landed is silent (known as the fourth silent beep)—this is the exact frame where the actor must begin to speak the line being replaced, otherwise referred to as “first frame of modulation.”

The idea was that the actors also watched their physical performance projected up on the screen. There was no need for laborious grease pencil cues to be marked on the film, as the three beeps prior to action provided them with an accurate rhythmic cueing. The actors had a chance to watch themselves and became quite aware of things about them in the movie realm that they might want to react to and that might influence their new performance.

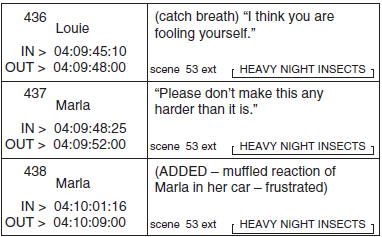

Figure 16.1 Here are three ADR cues that you can use to practice your technique and develop an understanding of the process. (The practice session can be found on the interactive DVD that is included with this book.)

This was a great toy. The studio that I was working at in 1977 was installing this kind of automated technology on Stage C, and I became very involved in this new process. But we very quickly discovered that some actors are perfect for ADR-style re-performing and others are totally intimidated by it, some to the point that they would devise all kinds of strange personal techniques in order to face the microphone.

Many who supervise performing talent on an ADR stage often notice how many actors are distracted by the beeps that precede the dialog cue to be re-performed. They are not used to hearing the beeps and especially not used to the rhythmic timing. I have therefore decided to include a kind of rehearsal exercise for those who would like to be better prepared before stepping onto an ADR stage costing many dollars by the minute.

For those of you who are interested in a little practice exercise before you attempt doing it on the real ADR stage, I suggest you use the practice session provided below as you listen to and emulate the three cues on the DVD provided with this book; you will find it under the DVD menu button ADR Practice.

The Practice ADR Lines

Just as you will experience on a professional ADR stage, you will hear three rhythmic beeps, then a piece of production dialog, the line intended to be re-voiced. The beeps and dialog cues are repeated four times, to assist you in getting used to the rhythm of the beep cues and the silent fourth count which is the cue to lip-sync your voice against the production dialog. The Colin-Broad streamer is also incredibly useful for Foley cues. But we will talk about that later when we discuss Foley in Chapter 17.

To assist you in understanding the use of automated Colin-Broad streamers, all of the ADR practice cues have Colin-Broad streamers animated into the visual picture. This terrific automated system really helps the actor as the visual line moves across the screen from left to right in addition to hearing the three preceding one-frame beeps.

To further the practical realism of line replacement, the practice cues have noisy ambiences, making it difficult to hear the original dialog at times. As you listen to the DVD cue with the beeps and production cue repeated six times, try to repeat the line in perfect sync. As you master the ability to match sync, change the inflection and performance, while still keeping the temp and rhythm in perfect sync. This should help any aspiring actor overcome the fear of working with the beeps and better understand what is expected in working on today's ADR/looping stage.

Aspiring actors, in both film and especially theatre, who want to be trained and prepared in the technical needs and expectations of ADR, will want to acquire the separate ADR/looping exercise DVD, which is available separately from this book. It has over a hundred ADR cues, along with cue sheet visuals that provide a boot-camp training to properly prepare you to go to the ADR stage and do it for real—in front of the director and producer!

The ADR Supervisor

The ADR supervisor, more than any other postproduction craftsperson, interfaces and works with performing acting talent. When temperamental or difficult talent is involved, the producer's and director's first concern is who handles the ADR responsibilities— and politics.

Some actors love to ADR. They see it as a chance to get back on stage and improve their own performance, to massage it, fine-tuning it in a way not possible on location. On the other hand, many other actors dislike ADR immensely. They are intimidated or inhibited by the ADR stage process. To them, the on-screen sync track was the magic performance they provided while filming the scene on location. Many actors do not listen to the production track with a discerning ear. They only hear their own performance and, once satisfied, often refuse to loop a requested cue. Many are not audio aware. These actors do not always notice the intrusive airplane flying overhead marring the recording; neither do they hear the distorted brittleness in the track where they shouted or suddenly burst forth in a dynamic shift, catching the production mixer off-guard causing the voice to be overmodulated.

This is where strong and politically smart ADR supervisors really earn their salaries. If a supervisor gains an actor's confidence that he or she is sincerely interested in improving and magnifying the performance, the actor almost always defers to the opinions and recommendations of the ADR supervisor.

An ADR supervisor does not always have to be the best ADR editor in the world (one can always hire ADR editors with reputations for cutting good sync), but the ADR supervisor must appear on stage neatly dressed with a professional bearing of calm self-confidence. The supervisor also must be extremely well organized, able to locate the right paperwork at any moment. If the supervisor does not have the answer literally at the fingertips, he or she must know where and how to get it in a timely manner without fuss.

The ADR supervisor must articulate clearly, to the actors as well as the director and producer(s) as needed, why certain cues are added and how they will improve the outcome of the final soundtrack. The ADR supervisor should not give the perception of being just the bearer of bad news or a presenter of problems, but rather of a professional presenting solutions. The ADR supervisor works hard, surgically gleaning out problematic dialog lines (for both performance and technical issues). He or she compiles a complete list of lines to be looped and devises tactical solutions for gaining access to remote actors not available for formal looping sessions.

Nothing is worse than being on an ADR stage or, even worse, on the re-recording stage and having a director or producer notice that lines were missed. It is bad enough when a director or producer decides on additional dialog needs after the fact; it is altogether a most undesirable situation to overlook lines that either clearly were requested in the initial spotting session(s) or were not gleaned out by common sense by the ADR supervisor while cueing the ADR lines at the workstation.

Listen Carefully to the Production Track

One pitfall that the director, picture editor, and producer(s) constantly encounter is losing touch with their production track. Remember, they have lived with the picture and their production track for weeks, often months, and on occasion even years. They know every word, every production sound effect, every dropout, every flaw. They have grown so close to it, however, they have lost the ability to hear it anew, as heard by an audience for the first time. It is often very difficult to convince directors and producers that a dialog line must be looped when the repetitious playback of that line is indelibly etched in their minds.

In a spotting session, I hear a problematic line. The director, picture editor, and producer are not flagging it. I hold up my hand. “What did they say?” Invariably, the director or picture editor will tell me what the actor said instead of realizing that my not understanding the line was related to its lack of clarity.

The best ally a supervising sound editor and ADR supervisor can have is the dialog mixer who helms the ultimate re-recording of the project. Many times a director or producer disagree with or try to badger the ADR supervisor, claiming nothing is wrong with a particular line. “You can make that work.” However, when the dialog mixer says to loop it, nobody questions it. After all, the dialog mixer is the ultimate authority through whom all dialog tracks must flow. He or she has the power to bounce the reel off the stage and refuse to mix it if the material cannot be made to work because of the way it has been prepared. It is for this reason that, as supervising sound editor, I always insist on having the sound facility set in place and the mixing crew contracted at the outset of commencing the postproduction sound editorial chores. The first thing I want is an interlock running of the picture with the dialog mixer, who usually helms the stage.

Naturally, I have my dialog editor (responsible for cutting original production tracks) as well as my ADR supervisor on stage for the running. More important, I want the director, picture editor, and producer(s) in attendance to hear exactly what the dialog mixer says about one cue or another. The dialog mixer runs the production track through the very mixing console used during the predubbing process. Often, the picture editor, director, and producer(s) hear the track truly for the first time, through quality theatrical speakers that are extremely transparent; they do not color or hide the flaws or warts of the recordings—all is revealed.

Many veteran dialog mixers explain that they have a three-point rating system as the team discusses the various dialog lines. If they rate it a “one” that means they have no problems with the technical characteristics of the line and can make it work; however, if they want to loop it for performance reasons, that is the call of the director and/or producer(s). A “two” means they do not like what they hear. Either there is a fringy edge (usually the threshold of distortion) or some kind of hum or noise, such as overhead aircraft, offstage traffic, or other intrusive sounds. The dialog mixer feels that he or she can work with the line if necessary, but would rather have it looped. If the mixer rates the line a “three” that means there is no choice but to loop the line, as the dialog mixer cannot equalize it or work with it to make it sound right. Do not even argue with the dialog mixer about his “three” count; even actors who have died can and do have line replacement done by soundalikes.

From time to time the dialog mixer pauses and lays on a few equalization moves or runs the sound through a universal dip filter to make sure that some offending noise can be notched out without encroaching on the characteristics of the voice. By the time the running is over, there is usually no question as to the scope of work to be done. The mental alignment of the sound editorial team and picture editor, directors, and producer(s) becomes fairly well set. With a short conversation regarding tactics of dialog preparation and perhaps other options to save certain critical lines, such as using Sonic Solutions or renting specialized signal-processing gear for the dialog predub process, everyone leaves the running focused on the job ahead.

Having an interlock running with the dialog mixer at the beginning also relieves the mixer of responsibility with you. It is one thing to show up on the re-recording stage for dialog predubs and have the dialog mixer zinging the sound editors because something was not done, but, when the dialog mixer is part of the decision-making process from the beginning, he or she is bound to the sound editorial team as well as the director and producer(s) by what was counseled before work began.

Crushed Schedule Trends of Mega-Monsters

Several ADR supervisors have shared the nightmare trend, especially on huge accelerated schedule mega-budget pictures, that they rarely even get a chance to have an actual and realistic ADR running as described in detail above.

Nonlinear technology with Final Cut Pro and Avid makes it easier and easier for picture editors and directors to put in visual special effects (as work in progress) and have a sound team (either for temp work only or the eventual actual sound editing contractors) start developing and make crash-down temp sound mixes long before the picture even gets to a point of being considered ready to turn over to sound editorial.

R.J. (Bob) Kizer is one of the industry's more respected ADR supervisors (Steven Spielberg's version of War of the Worlds, The Terminal, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, Catch Me If You Can, the 2000 version of Planet of the Apes, X-Men and X-Men: The Last Stand, Anna and the King, The Siege, Alien Resurrection, to name a few). He confesses that he often only gets his first real interaction with the picture editor and director about what lines to set up and cue for an ADR session during the first temp dub.

I personally find this appalling—certainly not Bob's choice—but it is important to take notice of the inevitable evolution of how things are being done: not for art form's sake, but for schedule and business considerations. Often, these decisions are made by those who do not understand the collateral costs that are incurred by what might seem like expedient practices, but, in fact cost untold wasted dollars due to ignorance of the process.

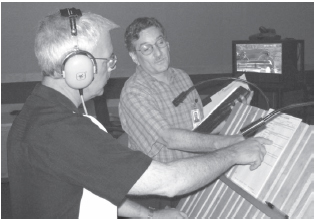

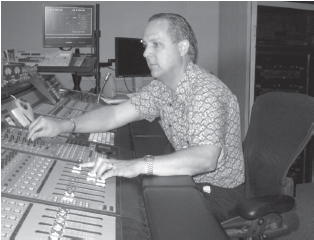

Figure 16.2 On an ADR stage, R.J. Kizer clarifies a point for David Kulczycki before he replaces a dialog cue. “One thing you have to master right away as an ADR editor is when to speak up and when to keep your mouth shut. You won't always know when you failed to do the former, but you will quickly know when you failed to do the latter.” (Photo by John LeBlanc.)

Tighter budget films cannot afford that kind of technique, and are better served by the ADR running technique as we talked about earlier in this chapter. But, it is vital to understand how and why certain techniques and trends are constantly evolving and the professional ADR supervisor will know how to shift gears from one technique to another, depending on the client and the studio involved.

Kizer has a few thoughts to share on the opportunities and discipline of ADR (and/or looping):

ADR has changed a lot from how it was done 15 years ago, and it is on the verge of changing yet again. The transistor revolution of the 1950s brought about the introduction of “Automated Dialog Replacement” in the late 60s and early 70s. The computer revolution of the mid-80s brought about the use of personal computers in the compiling of cueing information for ADR sessions. There must be at least eight different cueing softwares out there. (And who knows how many are floating around Europe and Asia?)

Cutting movies on the Avid and Lightworks has made re-cutting much easier and less labor intensive. Consequently, ADR editors must do their cueing on some kind of computer system just to keep up with all the changes. On Master and Commander, for example, I had a new version of the picture turned over to me every Friday. It would take me 8 days to conform my programming. As you can see, I quickly fell behind. I then had to conform my programming to every other version and gamble that I wouldn't be called to the ADR stage during a version that I had skipped.

Back in the days of shooting ADR on film and mag, I used to allow 10 minutes per cue. Today, I allow 4 minutes per cue. These days it is extremely rare to encounter a location mixer who only uses a reel-to-reel Nagra to record the production track. Thankfully the days of using a DA-88 are behind us. Nowadays, more and more location mixers are using hard-drive recorders (like the Deva). Production dialog is now routinely coming to us as 48 kHz/24-bit, broadcast Wave files.

Likewise, ADR is being recorded at 48 kHz/24-bit. Many ADR stages in Los Angeles and New York use Pro Tools as either the primary or secondary recording device. (Todd-A-O is still holding on to the Fairlight, but that will soon change.)

On the set, location mixers are using combinations of radio mikes and boom mikes to record the track. On multichannel recorders, they will assign individual actors to specific channels and place the boom on a separate channel.

For the 2005 remake of War of the Worlds, the production dialog was recorded across 8 channels. Channels 1–5 were individual radio mikes, channel 6 was the boom mike, and channels 7–8 were combines (bumped up by 8 dB) to be given to sound transfer for transfer to mag stripe—Spielberg likes working with film and mag, and so he has his editor cut his movies on a Moviola.

Some location mixers are very lazy and they take the radio mikes and the boom mike and combine all the signals into one channel and leave the other channels blank. It's true!

As a result of this multi-mike recording situation, many ADR editors are having their ADR recorded with two mikes: a traditional boom mike (either a short shotgun like the Sennheiser MKH 416 or MKH 60 or the Neumann KMR 81) and a lavalier microphone. So the ADR editor ends up with two channels recorded per cue. Both channels are cut and presented for predubbing. The dialog re-recording mixer will then decide which channel to use or use a combination of the two, whichever way matches the production track the best.

As you can guess from the above, if production dialog has 8 channels per “line,” then the edited Pro Tools session could easily be 64 channels wide. Usually the dialog goes through and strips out the channels that are not needed. So the edited session comes in around 12-16 channels wide.

The edited ADR session can be extremely wide; two channels per cue, plus however many alternates the director asked for, split for on-stage/off-stage treatment, and phone and TV speaker treatment—you can end up with 72 channels of ADR being presented for predubbing. (Personally, in ADR I have found only two specific instances where I was glad I had the lavalier mike recording. All the other times, we have only used the boom channel.)

More directors today do not know their craft nor do they know anything about any of the other crafts. Their sense of hearing is severely skewed to listening to extreme rock-and-roll music. Some show up to the final mix after having inhaled several lines of cocaine. Drugs like cocaine increase the heart rate, which will increase blood pressure. That sends more blood to the head, and the increased pressure affects your hearing. Things tend to sound more muddy. It's like having water in your ear. So directors start complaining that the dialog sounds too muddy. And the mixer is forced to EQ everything higher, so that dialog starts to become shrill.

Richard Portman always used to say, “sound is round.” By that he meant sound is a medium that should not be cut jaggedly like picture. Sound has an approach, a by, and an away. If you chop it all up, it becomes hard to listen to, and eventually the brain will tune it all out. Film editors like to cut sound as discrete blocks of events, just as they cut their picture.

They want to hear the car when they see the car. If they don't see the car, they don't want to hear it.

ADR Cueing R.J. Kizer, supervising ADR editor on ADR cueing:

In England, a device was created by Colin Broad called the Video Streamer. It had a software that allowed the operator to enter all the event addresses (cues) for a character, then it would trigger an electronic streamer or wipe for each event without having to stop in between. This allowed an actor to ADR an entire scene as a single take, if he so desired. So far, Disney and Fox have installed this box and software on their feature ADR stages. I have used it successfully (it can be a bit buggy) on three features, most tellingly on War of the Worlds.

Meanwhile, an outfit down in New Zealand has come with something they call VoiceQ. This uses a QuickTime movie and track. The operator loads in the QuickTime movie and sets the starts and stops for all the cues by marking the guide track in a timeline. You type in the dialog for the cues in a special window. Now, the software analyzes the track for each cue and then displays the dialog on a running subtitle banner on the picture. The letters of the words are squeezed together or stretched out according to how fast or slow the word was said on the track. This eliminates the need for the Actor to look down at his script as he is speaking his lines. All the dialog is up on the screen.

Each cue will be triggered automatically as the film is running, allowing the actor to do as many cues in a run as he wants. And like the Colin Broad Video Streamer, the software allows for the importing of cue data from other software via a tab-delimited text file. I have been lobbying Fox to get VoiceQ. I believe the software was originally developed to accommodate foreign language dubbing, but they have used it on Lord of the Rings and King Kong for principal ADR.

APPROPRIATE USE OF LANGUAGE

Language is a very delicate and extremely important part of the soundtrack. So few producers, directors, or writers truly understand the ramifications and broad audience enthusiasm for their film because of judicious and careful use of profanity in the dialog track. This is not about what previously was known as the Television Network Standards and Practices Board. This is a question of common sense and a calculated decision on the part of the producer of defining the audience for the film.

In an industry immersed in an assault on the senses, where we are exposed to extremes of cinematic content, most of the new generation of filmmakers unfortunately is desensitized and perhaps suffers from ignorance of this controversial and delicate subject. Seriously ponder for what audience you have been making the picture, and then rethink the use of profanity or slang used in the script. I have witnessed several projects that could have done much better commercially but were banished to a harsher MPAA rating because of the careless use of blasphemy and profane dialog.

Not an issue of Victorian prudishness, this is the experience of being associated with over 100 theatrical motion pictures, watching their creative evolutions through to box-office success or failure, and witnessing elements that made them successful and those that weakened them, turning off audiences. The topic is broached here because it is during the looping process that you may wish to rethink your dialog track through one more time with a critical eye toward this cause and effect; you still can make changes and improve the film's commercial worth.

Aside from primary content consideration, you must address television coverage. After you finish the M&E (foreign) mix, you will need to prepare a television version. You will not find an official no-no wordlist anywhere. Probably out of fear of violating the First Amendment, nobody wants to dictate and formally publish such a no-no list, nor will I. However, many sound editorial firms, especially those dealing with network television, have lists compiled from meetings and verbal edit strategies. Of course, the list is constantly changing. At one time, certain words could not be said on television or even in movies, and now they are heard on a regular desensitizing basis. Each network and cable channel has its own threshold of acceptance.

Determining what is profane or what will trigger a harsher MPAA rating is not as obvious as you might think. The word hell is a good example, an extremely common and virtually everyday word that has lost much of its impact. If an actor says, “Oh, what the hell,” this is not a problem. If an actor turns to another actor and says, “You go to hell!”, this is a problem, for now it is used in a damning way against another human being. Therein lies the difference.

The most powerful and surefire trigger to not only doom your film to a harsher MPAA rating but also to turn off a huge cross-section of the audience is the use of blasphemy. Should an actor place the word god in front of the word damn, the most profane word has been uttered; yes, it is even worse than the f word.

It is just amazing to me how warped the cable censorship community has become. American Movie Classics and other popular so-called family channels will bleep out the s word, yet they will leave in the harshest of all obscenities by leaving the god words in. This is not an indictment based only on Christian ethics. God is a global term that applies to the specific names that define the pinnacle deity of almost all religions; therefore using it in a derogatory way is worse than hearing Al Pacino say the f word so many times in Scarface. If you do not understand what I'm talking about, then I suggest you check out the Ten Commandments that Moses brought down from the mountain top.

The body count, bullets, and blood mentality that desensitizes the audience will (and is) eroding the viewing tolerance. I should know. I have worked on many films that I would not, by choice, go to see. I have been bombarded by images and language that for long periods of time has desensitized me. It took months to return to a mental state where I could act and react to things in a normal way (whatever that is supposed to be). But you are never really the same.

Hollywood argues that their studies tell them the kinds of movies that the public wants to see. Statistical studies will yield information in exactly how you present the question. We did not believe Hollywood's box-office studies of the public taste and demand, and after making our own study it quickly revealed why. Fewer and fewer middle age and older moviegoers were going to the theatre because of the product, not because of a lack of desire to go see a movie in a theatre. It becomes kind of a chicken-and-egg argument, doesn't it?

After conducting a study of moviegoers, as well as patrons who rented from local video shops, we discovered that language, without a doubt, was the number-one reason why a significant number of potential patrons stopped going to the movie theatres. At the very least they had become far pickier about which films they wanted to see. Many of their comments surprised us, especially in regard to the specificity of objectionable words. For instance, many viewers reacted very badly to the word crap or crappy in film dialog, saying they actually would prefer to have heard that other overused defecation s word cliché.

While it is true that some of these comments came from areas many refer to as the Midwest or the Bible Belt audience, filmmakers forget that that audience accounts for a giant share of income and can certainly wield powerful critical acclaim or disapproval. Have you ever considered the collateral loss of dollars that you do not know about, because you did not know what was possible to begin with? I think the movie The Rookie, starring Dennis Quaid, is an excellent example of a picture that has heart, passion, emotion, action, interesting photography, good sound, and music score and yet does not have one curse word in the picture. By the way, it was rated G for all you Hollywood-hype executives that spout that G-rated films are poison at the box office.

This is not just a lesson in ethics or morals, but a good business lesson in possibilities. Just remember for which audience your film is targeted for and analyze your visual image and dialog track with a critical eye and ear. It will tell you what must be done. You may also find it interesting that since, as we have discussed in this book, foreign sales stream income now dominates the domestic market, you should pause and think through the tastes and tolerances of foreign markets. Each overseas audience market has their own thoughts and reactions to film language. Sometimes it may be translated out, but certain words are universally recognized. This is not to say that you cannot or should not make R-rated films. They definitely have their market. This is about recognizing what market your film is really speaking to and make sure that the content speaks the presentation to match.

A few years ago I was supervising the sound on what should have been a cute little PG-rated robotic film. We had just sat down to commence the spotting session when the lead actor turned and used the god word, not once, but several times. I raised my hand for the editor to stop. I turned with a puzzled expression to the producer, “so you're making an R-rated film?”

He recoiled at my comment. “What gives you the idea that we're making an R-rated film? This will be rated PG!”

I shrugged, “That's what I thought your market was going to be. But you sure have an R-rated film now.”

The producer asked how I came to assume that. I explained that after working on more than a hundred theatrical motion pictures, on many of which I am privy to the interactions of the producer and the MPAA, I have come to know what will trigger certain ratings, and using the god word will get you an R rating.

The producer scoffed at me. What did I know? I was just a sound editor! Several months later, when we commenced the final re-recording process the producer burst onto the dubbing stage with a deluge of profanity. How could the MPAA have given them an R rating? I glanced knowingly at the head mixer who smiled with an unspoken I-told-you-so acknowledgement.

Rather than take the time to go back in and loop the offending lines and resubmit the film for a new MPAA rating, the producer did not understand that it was this simple language issue that garnished the R rating, so the lines were never replaced. Consequently the picture was released as an R-rated film which was not the audience for which it was designed for. The film failed miserably, all because of a dozen god outbursts in the dialog track.

Finally, if you do not want your film to play on a well-known cable channel and have muted dropouts in the soundtrack because you did not supply a television version, accept the advice from the ADR supervisor regarding getting television coverage while you have the acting talent on stage for the primary ADR session.

CUEING ADR LINES

After a thorough run-through and discussion with the director and producer on actor performances and availabilities, the ADR supervisor goes through the film to cue the dialog, noting both replacement and added lines to be recorded.

Before computer programs, ADR cue sheets were always typed. A real professional never took handwritten ADR cue sheets to the stage. Never give an actor a handwritten ADR cue sheet, unless you are adding or collaborating on new dialog on stage with the actor. The neatness and precise look of the ADR cue sheet are your ambassador of professionalism and trust. Watch for misspelled words or crossed-out lines with handwritten corrections. Many actors are intimidated by the ADR stage already. If you give the actor handwritten cue sheets, you do not instill confidence and inspire the actor; you may find yourself soon replaced and it may not be up to your supervising sound editor; he or she may be compelled by the director's or producer's office to do it.

The Traditional ADR Form

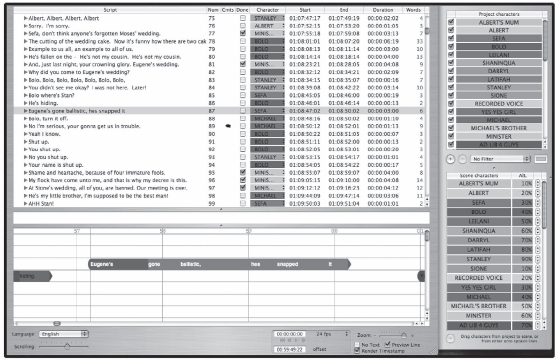

Note that each ADR line in Figure 16.3 has a cue number. Almost all ADR supervisors use the reel number as the first designation, so all cues in reel 4 are the 400 series (401, 402, and so on). Many supervisors leave a blank box in between each cue, allowing space to add lines on the spur of the moment, but also making it much more comfortable for the actor to find and read the lines in the dim light of the ADR stage. The actor must concentrate on the image projected on the screen to match sync, and not waste time to find the written cue on the page.

List each part by the character name, not the actor's real name. Every ADR supervisor has a specific technique and preference as to how to prepare ADR sheets. Many supervisors list ADR cues just as the ADR form is displayed in Figure 16.3. In other words, ADR cues are listed in a linear order, in sequence of performance, listing each character. Other ADR supervisors choose instead to put all the lines for each character on a separate page. Their contention is that this is not as confusing to the actor on the ADR stage. I simply take a yellow highlighter to all of actor 1’s lines, and on another copy I highlight all of actor 2’s lines, thereby making it immensely easier for the actors to focus on their own dialog requirements.

As supervising sound editor, I prefer ADR sheets in linear order. With today's computer software, it is so easy to extract per-character variants from the master cue list and print them for the actor on stage, but I do not want to fumble through a dozen separate sheets looking and accounting for lines of dialog.

Each line has a “start” and “to” designation. This designation either is listed in feet and frames or in time code. Many veteran theatrical editors still like to work in feet and frames, but video outputs from the cut picture are offering fewer and fewer opportunities to use feet and frames. Aside from personal preference, a few ADR stages cannot even display feet and frames anymore, and so time code is the only choice in those instances. (Always check with the stage before starting this task.)

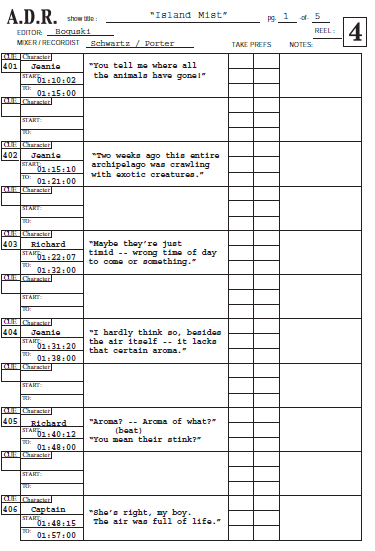

Figure 16.3 This is a classic example of a traditional ADR form.

When cueing the line to be ADR'ed, list the exact frame in which the first audible modulation can be heard—exactly! At the end of the line, add 1 foot extra for overtones to die off. Not all ADR mixers like their start cues the same way. Some want it 2 frames prior; others want it as many as 8 frames prior; still others want it right on the frame of modulation. You will probably use more than one ADR stage to complete all ADR work for the picture. Each stage may want the start cues slightly different. Either tell the mixer that all your cues are right on the frame so that specific preferences can be utilized, or print out new sheets with the preferred frame specifications already listed for each recording venue.

The ADR supervisor soon has a list of the stages, both local and around the world, that will be dealt with to accomplish the looping chores of the picture. The ADR supervisor discusses preparation preferences as well as media requirements from the ADR mixer and/or audio engineer of each facility. It often is necessary to prepare separate ADR sheets for individual ADR facilities, customizing the data to best accommodate that facility's own capabilities or limitations.

Most good ADR supervisors have an added line of notations for each cue. They list a reason why the line is to be re-performed (e.g., noise, distortion, performance, television coverage, and so on). This has developed out of frustration from ADR supervisors, supervising sound editors, producers, directors, and re-recording mixers who, in the final analysis, have to make it all work. Initially, the producer or director perceives that the dialog for the film is basically in good shape and does not require much looping. Then the ADR supervisor and supervising sound editor run the reels with the re-recording mixer on a dubbing stage to analyze the true quality and nature of the production sound. It never fails to shock the producer and director, who have never truly heard their production track in this theatrical environment, just how bad and brittle their soundtrack is.

Now come the lines added because of unwanted vocal overlaps that went unnoticed before, for instance, airplane noise not detected on the little speakers of a picture editorial workstation. The rhythmic ticking was not noticed because of early morning condensation impacting the microphone diaphragm. If you loop the passenger character in the front seat of the car talking, you either must loop the driver or cross-fill all the noise from the driver's dialog under the passenger character to avoid a series of checkerboarded dropouts, which ultimately accomplishes nothing if you were intent on getting all that noisy background out from behind the passenger character's lines in the first place.

Now the ADR lines start adding up. At an average of 10 minutes per line to successfully record, the producer and director get nervous. Their good-shape dialog track is now escalating into several hundred, even a thousand-plus ADR cues. Then you send an ADR kit to South Africa to an actor on location but with access to an ADR stage in Johannesburg for an afternoon. The budget cannot afford for the ADR supervisor to fly down there to oversee the session. What comes back is a marked-up ADR sheet with only a fraction of the ADR lines done. The actor either does not understand or does not care about the technical problems of the scenes. The actor considers his or her performance fine.

I received a ¼” back-up master from an ADR stage in Florida, where a name actor had performed his ADR session unsupervised. Without due consideration of why the ADR cues had been written up and without calling the editor in Los Angeles to ask why he was expected to loop certain lines, he arbitrarily decided not to loop some lines and to loop others. As I ran the ¼” back-up master, I could hear the actor scoff as the film rolled. He demanded to know what idiot had cued the lines. He crossed out a line and wrote “omit.” Of course, he did not pay attention to the background noise, which the ADR supervisor knew would give the dialog re-recording mixer absolute grief later. Guess who caught the criticism from the re-recording mixer when he heaved a sigh and said, “I can't make this work! Why didn't you loop this line?!”

By making notes as to why the particular ADR line has been cued, the ADR supervisor not only informs and educates the actor to gain cooperation but also makes a paper trail record that may be necessary to prevent later blame and to show the producer and studio executives that the ADR supervisor had prepared the job correctly in the first place.

Note in Figure 16.3 the six squares to the right of the ADR line. The ADR supervisor keeps a close record of which takes are most desired, kind of like the circled takes on a production sound report. Before direct-to-disk digital recording systems, such as Pro Tools, ADR was recorded to multichannel magnetic stock. At first it was 3-channel 35-mm fullcoat, and when the 4-channel 35-mm head stack came out in the late 1970s, we were thrilled to have one extra channel. Then stages started adapting 24-track 2” magnetic tape, especially when Dolby Laboratories made the Dolby A 24-channel noise reduction encoder/decoders. This became even more popular with the Dolby SR (Spectral Recording) encoder/decoder. Cue sheets during these years had 24 square boxes for the ADR editor to keep notes in, especially in keeping what take was on which channel.

With today's direct-to-disk nonlinear recording systems, “what channel” is irrelevant. It becomes a matter of “what take,” as it all resides on the hard drive unless otherwise thrown away by the user. It really falls to the ADR mixer assistant to help the mixer keep the take numbers straight, as after recording a line, the mixer would need to tap twice on the recorded audio track to rename it. That renaming would become critical for future reference. It becomes very easy to record numerous takes before the director chooses one or more to “print,” which is an old term that meant that the sound transfer department should make a transfer copy (in whatever medium was required) for the ADR editor to cut. With today's digital technology we do not “print” anymore, though the term still sticks, it just means that the ADR editor will want to pay strict attention to the director's choices. The ADR supervisor also makes notes as to how to cut the line. The director may ask for the first part of the line from take 3 with the second part from take 9.

ADR Software to Further Automate the Process

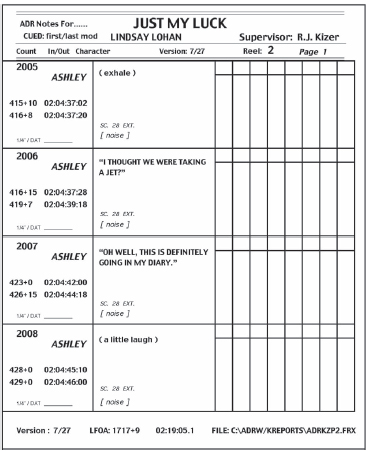

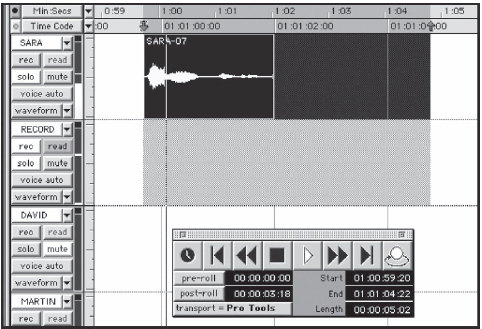

Figure 16.4 is from the ADR cue sheet for the character Ashley from the romantic comedy Just My Luck. Note that as in the traditional ADR form, the information disciplines are the same with a few important variations.

The header lists the name of the film, the name of the actress (not the character she plays) who will be replacing the lines cued, the name of the supervising sound editor (R.J. Kizer). Note the piece of information on the far left hand side of the header. This is very important information—Cued: First/Last Mod. This tells the ADR mixer exactly how the ADR was cued, that there were no pre-frames built into the cue, as was the practice a few years ago.

The next line of information tells us the count (what cue number the line is). As in the traditional ADR form technique, the first number denotes what reel of the project is being cued. The last three numbers refer to each cue in numerical order.

The next item of information is the In/Out, referring, of course, to the first frame of modulation of the line to be replaced and the last frame. Before automation ADR software that will actually drive the recorders, we usually built in one extra foot after the last detected frame of modulation. This allowed for overtones so they would not sound clipped. Note: The In/Out counts have both 35-mm feet and frames as well as time code.

The next item of information is the name of the character that Lindsay Lohan plays in the film Ashley.

The next very important piece of information is the version identification. On Starship Troopers I had to keep 18 version cuts straight, so you really need to know to what version the cue feet and frame/time code numbers sync with.

Figure 16.4 A computer program printout for the first few ADR lines for R-2 of Just My Luck.

In this case the date (July 27) is used as the identifying version number.

The next item of information tells us what reel has been cued (in this case reel 2).

The last item of information on this line is the page number.

Note the fine print under the In/Out footage/time code numbers. ¼” / DAT roll designation. The ADR mixer will tell the supervising ADR editor in what ¼” or DAT roll he or she can find the back-up protection.

There are three pieces of information in the next box to the right of each cue number. The first bold type is obviously the cue itself. If it is not actually dialog, but breaths, grunts, sights, exhales, or other vocal peculiarities, they are listed as such in parentheses. Dialog is listed in quotes.

The second piece of information in this box is in fine type near the bottom of each box—Scene Number, Int. or Ext.

The third piece of information in this box is also in fine brackets under the scene number—the explanation of why the line is being replaced. In this case, because of [Noise].

At the bottom of each page, the software will repeat the version date (or number). It also lists the LFOA (also known as LFOP; the last frame of action). In this case it is 1,717 feet plus 9 frames. This tells us instantly that this is an A-B reel, and not the traditional 1,000-foot reels that were described in Chapter 7. The next number is the time code frame of the LFOA (02:19:05.1; this tells us that it is reel 2, 19 minutes, 5 seconds, and 1 frame).

The next piece of information tells us the exact file that Kizer produced to make this cued report.

All that said and done, there are many ways to approach producing ADR cue sheets with software. You can spend a great deal of money (on average $2,000) or you can use much more cost-effective variations.

One of the reasons why you really want to use properly authored software for cueing your ADR is that the supervising ADR editor can show up on the stage, hand a disk of the file that he or she has produced (a TAB delimited text file).

The mixer will take this disk and enter the file into the computer system in the stage's recording booth equipment system. One popular system is the Colin-Broad VSP2, which allows direct entry of cues from a remote keyboard, downloading an ADR list to both SR/MR Controller and the Video Streamer (CBServer Software). It requires the Video Streamer with RS422 processor board and EPROM update. Set the SR/MR system to Auto/ADR—the list will be entered on both the SR/MR and the Video Streamer. Many major ADR stages today are set with this system to read the time code numbers and automatically set up each cue.

The Video Streamer is a wipe-streaming projection device that will automatically project a white traveling wipe or streamer across the screen, just like we used to make by hand in the old days with a grease pencil and ruler, drawing them right onto the 35-mm picture dupes. For further information, you can check out this and other devices by Colin-Broad at their website, colinbroad.com.

VoiceQ—for ADR, Foley, and Dubbing

We all know that dialog replacement is an integral part of filmmaking, and depending on your director, it can be a nightmare experience. We who have had to endure the instant preparation expectations of clients and suffered the promises of so many software products have gotten tired of the big-If syndrome. If you rename your audio tracks with certain key letter inclusions so that the software will understand what to do with it… . If you have enough money to afford the huge expense that certain packages entail… . If, If, If!

KIWA International Ltd., out of Auckland, New Zealand, has developed a system that really does seem to fit the supervising ADR's dreams and fantasies, VoiceQ. After extensive chats with R.J. Kizer, and looking into the product myself, I contacted David Kite of KIWA and invited him to formally present his product in this chapter where it is a welcome consideration:

It is common practice to re-record and synchronize the majority of dialog and sound effects after filming is complete. In addition, do not forget all the work that accompanies the translation of most movies into alternate languages for release in foreign markets.

The two most common forms of queing actors in an ADR session are streamers and 3 beeps just prior to the cue to be re-performed. A streamer works by cueing in the actor through the use of a vertical line that moves in succession across each frame until the event is reached, which is the cue to start. We just spoke of this technique by using the Colin-Broad cue projection device.

The 3-beep method aligns a loop with the movement on screen and cues the actor using a series of three audio beeps. On the fourth “silent” beep the actor reads the loop and attempts to match the voiceover aligned with the voice movements and performance on screen.

While these methods can be considered industry standards for expediting the ADR process, they are both highly inefficient. Multiple repetitions may be required to ensure accurate synchronization with the footage, time wastage often occurs in setting up and waiting for the cue event, and any dialog changes are made manually in the recording studio. The result is a significant loss of time, and thus reduced productivity and efficiency.

VoiceQ expedites the dialog replacement process during audio postproduction through visual on-screen cues. The Apple Mac digital software products and VoiceQ ADR and VoiceQ DUB can be standalone or integrated seamlessly with any Pro Tools and any other recording systems via MIDI time code. VoiceQ ADR was conceived for automated dialog replacement, which is the practice of re-recording parts of the dialog in the original language to obtain optimal sound quality. VoiceQ DUB has been designed for dubbing, the replacement of one language with another.

The principal function of both VoiceQ ADR and VoiceQ DUB is to scroll the dialog across the screen in sync with the film. This is achieved with such a level of accuracy that actors can literally see when to start each individual word that they need to speak, which makes their task considerably easier enabling them to give a better performance in considerably less time. Preparation of ADR sessions outside the recording studio further reduces cost and valuable recording time.

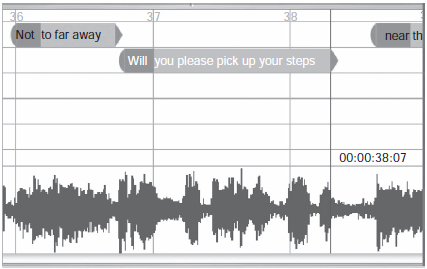

A VoiceQ session consists of the live video stream with the lines to be spoken by the actor scrolling across the bottom of the screen from right to left. At the left-hand side of the screen is a vertical line. When a word hits the line, it is time for that word to be spoken. Lines for different actors are distinguished by color and vertical alignment, allowing for multiple actors to be recorded simultaneously. Symbols and characters can be added to facilitate interpretation and expression of the dialog as well as for Foley and sound editing. A line may be previewed on screen upon request and a host of other features are available for all key production personnel. Although a multitude of reports for scheduling and other purposes are provided VoiceQ advocates paperless processes.

The VoiceQ Screen consists of three distinct sections. The Script Editor section enables input and editing of dialog, scenes, comments, time code parameters, character assignment, and progress tracking of each line.

The Timeline Editor section includes synchronization of lines, words and symbols, scrolling speed, zoom in/out, toggle text, time code, and preview line on/off. Selection of the language to be displayed and the FPS rate and Offset as appropriate. Play control deck for standalone mode. The Character Editor section can add and edit Foley category and characters, select dialog by character(s), filter by character, and change colors and altitude of dialog displayed on screen by character.

Figure 16.5 The main VoiceQ screen.

When a word hits the yellow vertical line it is time for the actor to speak that word. Synchronizing each word allows for gasps, breaths, and silence within a line. Text is overlayed live onto a QuickTime format of the film and can be output to an external monitor, TV, or projector. Overlaying of text enables changes to be made on the fly and immediately displayed on screen. Note that each character is color coded to allow for multiple actor recording.

Dragging lines and words using the audio waveform makes the synchronization process easy and updates all other areas of the application automatically.

VoiceQ provides a host of preferences to suit the user, actor, ADR supervisor as well as the audio engineer and mixer.

VoiceQ is Unicode, enabling the selection of any language for translation and dubbing for foreign markets. Some of the features of VoiceQ are:

• Scrolling synchronized dialog over video

• Simple drag and drop features

• Multi-language capability

• Manual and automated script input

• Spotting, detection, and adaptation functionality

• Frame-accurate cueing

• Feature-rich reporting and character filter functionality

• Real time on-the-fly script editing

• Works as standalone or in conjunction with Pro Tools LE and Pro Tools TDM systems

Figure 16.6 VoiceQ on screen output.

Figure 16.7 Synchronization of dialog.

• Includes MIDI time code generator

• Output through DVI- or S-Video to external monitor, TV, or projector

• Configurable on-screen presentations

• Automated file saving

• FPS or feet and frames

• Choice of scrolling or static script cue

• Automated line referencing, notes, and progress tracking

• Jog wheel option with user-definable key mapping

• Abundance of quick keys for common functions

Some of the VoiceQ benefits:

• Better for actors

• No more paper; read the script directly off the screen

• Record with other cast members for improved dramatic interplay

• Improved dramatic interpretation and comedic timing

Figure 16.8 VoiceQ Preferences.

Figure 16.9 VoiceQ Project Languages.

• Better for directors/ADR supervisors

• Reduced recording time leaves more time for creative play

• Make your script changes and display on-screen instantaneously

• Reference the original script against other iterations and languages

• Better for engineers

• Greater accuracy means halving the time spent in editing

• Perfectly timed streaming Foley symbols and notes give you greater accuracy and control

• Completing projects in half the time means quicker throughput of projects

• Better for producers

• Streamlined processes means less time and costs in actors

• Improved production standards mean lower costs in postproduction

• Greater accuracy gives you a better sounding and synchronized product

• Better for your business

• Simplicity of VoiceQ means you can diversify your business

• Financial and qualitative advantages of VoiceQ may make gains in margin and turnover

• Keeping your film secure on an external drive means you only need to plug it into VoiceQ when needed

Figure 16.10 Actor preparing to replace a line of dialog.

ADR STAGE: THE CREW

ADR Mixer

The ADR mixer must be highly experienced in the use and placement of various microphones and must know how to listen to the production track and match the colorization and timbre of the ADR stage microphone so that the actor's voice blends into the production track as seamlessly as possible. In addition, the ADR mixer must be a politician, knowing when to guide and handhold and when to remain quiet and step back.

The ADR stage is known for everything from making magic to provoking bouts of fisticuffs. Tempers flare and feelings get trampled. The ADR mixer de facto becomes both host and problem solver, but the mixer almost always has the last word. Most ADR mixers whom I have met are slightly reserved, politically smart individuals who know how to focus on the good of the show and how to guide the temperaments of all concerned toward a constructive end.

The great ADR mixers are extremely comfortable and smooth with their equipment. With what seems like effortless magic, the mixer rolls the tape, presses the in-line mike, and slates the multi-track and DAT back-up recorder. “Cue four-oh-three take five, channel six.”

A beat later the three rhythmic ADR beeps sound, and, on the silent fourth, the actor performs the line. Without being asked, the mixer quickly rewinds the tape and hits the talk-back button so all on the stage can hear. “Playback.”

The tape rolls, and everybody hears the production track. At exactly the right moment, the mixer mutes the production dialog as take 5/channel 6 plays back the new performance. The mixer smoothly slips out the production track exactly at the end of the cue so those on stage can get a sense of how the new line sounds.

Figure 16.11 ADR recording engineer Derek Casari prepares to record for an ADR on the ADR stage at 20th Century Fox. (Photo by John LeBlanc.)

We wait for a response from the director. Is it a circled take, and we go on to the next cue, or do we try another take of this cue? It is a circled take, and yes the director wants to try another one. The mixer calmly switches off channel 6. “save channel 6, moving on to channel 7.” The recordist makes the appropriate note on the ADR protection report, and they roll the videotape to try it again. The instant feedback may help ease the actor into relaxing about the process and help toward a successful and rewarding completion.

ADR Recordist

The ADR recordist supports the ADR mixer. The recordist is responsible for receiving either the film dupes or the videotapes of the picture prior to the ADR session. If the session is being synced to videotape, the recordist spins down to the 1-minute time code designation and checks if the tape really is drop or nondrop time code as advertised on the label. Many times people just assume the label is filled out correctly, and even more frequently, the video transfer facility fails to list the technical specifications at all.

If the videotape is drop frame, the visual time code numbers (note the semicolon for the frame count) jump from 01:00:59;29 to 01:01:00;02, skipping over 2 frames. Obviously, if the tape is nondrop, the visual time code numbers (note that it is a colon and not a semicolon for the frame count) simply flip from 01:00:59:29 to 01:01:00:00.

Once the time code rate has been determined and verified, the recordist makes sure that the proper number of multi-track audiotapes (such as 2” 24-track analog or 1” 48-track digital) have been properly degaussed and time code striped for the upcoming work. The recordist prepares all labels for the multi-track masters as well as the ¼” or digital DAT back-ups. The recordist also lays down line-up tones on all tapes, making sure that all channels are recording properly and that the stock is stable and reproducing properly. The recordist further confirms that the signal path from the mixer's console is patched through the noise-reduction encoders and that the right console fader assignments indeed go to the correct input channel on the recorder.

The recordist also does a shakedown run of the videotapes supplied by the ADR supervisor, making sure that the time code is reading correctly and that the production track on channel 1 is playing clearly. Videotapes are not all transferred with equal attention to quality or time code. The last thing you want is to run an ADR session and discover that your videotape has dropouts in the time code. If you do not have a good back-up tape at your disposal, the entire session can come to a screeching halt, or at least to a short-tempered delay.

At the start of the ADR session, the recordist takes the ADR sheets from the ADR supervisor and sets them up so that the mixer is only concerned with the business at hand. The recordist keeps all paperwork and organizational chores out of the mixer's way so that the mixer can focus on balancing the microphones and capturing the actors’ performances clearly without distortion or unwanted noise.

As the ADR session progresses, the recordist methodically and carefully maintains the back-up digital DAT, checking that each cue has its own program number (PNO) and determining which takes are requested by the director as “circled” takes. The recordist monitors the playback head of the multichannel, vigilantly listening for any breakup, distortion, or other anomalies that inhibit a successful audio conclusion.

Up to this point, another option to fix it existed all the way down the line from the first day of principal photography, but not anymore. Nobody else can fix it. You either get the recording clean or you fail. At the first sign of clicks, pops, distortion, or other unwanted noise, including squeaks from the actor pivoting around on a stool too much, the recordist flags the mixer (who may not be hearing it from the pre-record head position), who then asks for a retake or diplomatically informs the talent that they are making unwanted noise.

The recordist ultimately is responsible for seeing that the master multi-track is either delivered to the client, goes to the transfer department to transfer the circled takes to whatever medium the editor dictates, or downloaded into a digital workstation format such as Pro Tools.

Microphone Choice and Placement

A most important factor in good ADR recording is the choice of microphone. As discussed earlier, not all microphones have the same colorization or character. The ADR mixer needs to know exactly what microphones the production mixer used on the set, so that the same model of microphone is used to record the ADR.

Often I pick up a production roll and find no mention of the microphones on the sound report, not even the model or head stack configuration of the sound recorder itself is listed. Although many production mixers do recite an audio checklist at the head of each production roll before they roll their line-up tone, it must be assumed, as often is the case, that the production roll is not in easy access to the ADR mixer; if the production mixer had listed the recorder and microphone information on the sound report, it would be instantly available.

Figure 16.12 Two Sennheiser 416 microphones used on an ADR stage. Although there is no need to use windscreens indoors, the mixer leaves on the windscreens because they were used on the microphone during exterior filming. The mixer tries to recreate the exact colorization of the microphones so that the ADR lines better match the production performance.

At any rate, the ADR mixer needs to know the model of microphone used in order to duplicate the audio texture and colorization, so that the new ADR lines flow as seamlessly as possible with the original production material against which they are cut. Otherwise, the audience will be mentally yanked out of the performance of the scene because the ADR lines glaringly stand out from production.

Most ADR stages have two matching microphones set up for the session. The first microphone is approximately 2 feet from the actor, slightly higher than the forehead and angled downward toward the mouth. At this distance, a de-popper screen in not needed, but some actors have a well-trained stage voice that requires protection from their powerful “P”s (as Christopher Lee apologized to me once, “Ah yes, I have vented many a theatre.”)

The second microphone is placed farther back from the first, between 4 and 6 feet, depending on the perspective required. This microphone is also slightly higher than the closer mike. With this configuration, the ADR mixer can switch from one microphone to the next to achieve a more desirable perspective in matching the original production track. Without the two-microphone set-up, the ADR mixer constantly must get up, go out into the stage, and readjust the microphone position from cue to cue, wasting precious time and accelerating the fatigue and irritability factors. The only time to move the close-up microphone any nearer the actor is on those rare occasions when recording intimate whispering and extremely subtle vocals that require the microphone ultra close. Be very careful about the popping “P”s and hard consonants with this in-your-face proximity.

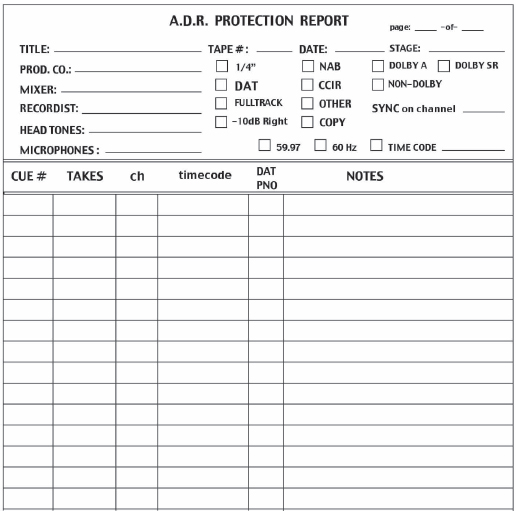

ADR Protection Report

The ADR supervisor sits on the ADR stage near the acting talent, interacting with them and the director. The recordist maintains the multi-track recorder and digital back-up DAT. The recordist keeps track of the ADR cue number and lists each take and its channel. If the back-up is made to ¼” tape, the recordist notes the time code start. If the back-up is being made to a digital DAT, the recordist notes the PNO that the DAT machine assigns to the tape each time it rolls.

The recordist also circles those takes the director and/or ADR supervisor want to keep. These takes are protected on the multi-track recorder. The mixer does not record over those channels if additional attempts at the performance of that cue are requested.

Figure 16.13 An ADR protection report.

Note that the protection report also lists microphones used, tape speed, whether noise reduction was used and what kind, and so forth. Always prepare these forms as if someone with absolutely no knowledge of your procedures and protocol is working with the material and cannot converse with you on the phone if they have questions. Additionally, a copy of the ADR protection report is kept in the multi-track tape box. A copy is also given to the ADR supervisor, especially valuable because of the DAT PNOs.

Several years ago a mixer shipped out a good amount of material in great haste without filling out the necessary information. He simply told the messenger that the transfer man should call with any questions the next day. Sad but true, the mixer had a fatal heart attack that evening. Also sadly, the transfer man was left with many unanswered questions.

ISDN Telecommunications Interlock

Sometimes it is not possible for economic or scheduling reasons that directors and actors can be in the same place at the same time. Increasingly, telecommunication ADR sessions are necessary. Say three actors in a film live in New York. The director must oversee their ADR session but also must remain in Los Angeles for another postproduction task. Do not fear, many ADR stages now offer digital interlockable sessions. Book an ADR stage in New York and schedule the three actors to show up for their lines. At the same time, book a small ADR or viewing stage in Los Angeles. Both stages hook up and interlock using an ISDN line. Logically, these kinds of sessions are simply referred to as “ISDN session”—that was a real stretch. One line handles the time code feed, while a second line handles the digital audio feed of the actors’ performance as heard through the mixer's console. A third line handles the communication feed for the director and/or ADR supervisor to communicate with the actors just as if they were on stage with them.

The New York and Los Angeles stages both have identical picture (film prints, videotapes or QuickTime video files) with matching production track. The third line with time code interlocks the Los Angeles videotape machine and slaves it to the mechanism of the New York machine. The digital audio feed is decoded through a quality digital-to-analog decoder on the Los Angeles stage and played through a good speaker system. The price of the hours of phone lines is a fraction of the cost of flying the actors to Los Angeles, paying per diem and expenses, or for the director and/or ADR supervisor to fly back to New York.

THE RETURN OF THE LOOPING TECHNIQUE

As frustration mounts over the issue that the director cannot get the actor to recapture the magic of the production track, one starts to look for alternatives. Naturally, if the production track just did not have that jet noise over the dialog, or if the actor had not been so far off-mike—the what-if's mount up like dead insects in a bug-zapper.

Forget the what-if's—you will just have to place more emphasis on giving the production mixer what he or she needs to record better production tracks for your next project. You have to overcome the frustration of the here and now. When you have acting talent that is not classically trained, you are almost always going to have to replace more dialog during the postproduction phase.

Almost all first-time actors are inhibited and intimidated by the beeps in the ears and concentrating on a poorly projected image of themselves on a screen or on a monitor as they try to match the lips in sync. As they have to pay attention to doing all of this, they cannot possibly concentrate on acting the performance. Isn't that what all of this is about?

The actress just could not make it happen. The stage clock was clicking off the hourly rate, the director was frustrated that he wasn't getting the performance, the actress could not walk and chew gum as the producer's thermometer was rising, foreshadowing an oncoming stroke.