Chapter 14

Sound Editorial

Ultra Low-Budget Strategies

“I know what I said—but now we're dealing with reality!”

- Steve Carver, director of Lone Wolf McQuade

You just finished reading about the structured, more traditional techniques and disciplines for recording, editorial preparation, and delivery of the myriad sound cues necessary to create the theatrical film experience known as the soundtrack—and you think all this book talks about is big-budget features with big teams of craftspeople to get the job done. Well, before we discuss the dialog editing, ADR and looping techniques, the world of Foley, music, and the re-recording process, I think we should pause and discuss the fact that a great deal of the work you will do will not and cannot afford the budget requirements to mount the type of sound job that you will find yourself faced with.

I assumed that as you have been reading this book you understood one extremely important axiom—the art form of sound does not change, no matter the budget and schedule on the table. All of the audio recording techniques, the science, and the pure physics of the soundtrack of a film do not change—only the strategies of how you are going to get your arms around the project and solve it.

The upcoming chapters regarding the dialog, ADR, Foley, music collaboration, and edit preparation in concert with the strategies of the re-recording mix process apply to the development of the final soundtrack the same way, whether you are working on a gigantic $180 million space opera or if you are working on an extra-features behind-the-scenes documentary for a DVD release or a student film. The only differences is the dollars allocated in the budget and the schedule demands that will, if you have been paying attention to what you have read thus far (and will continue to read about in the following chapters), dictate to you exactly how you are going to develop and deliver a final soundtrack that will render the fullness of the sound design texture and clarity of a sound budget with 10 times the dollars to spend, to as much as 100 times the budget that the blockbuster films command.

I could not have supervised the sound for 11 Roger Corman films if I did not understand how to shift gears and restructure the strategies of ultra low-budget projects. That does not mean that all sound craftspeople know how to shift back and forth between big-budget to ultra low-budget projects and maintain the perception of quality standard that we have come to expect from the work we do.

There are many who can practice their art form (whatever specific part of the soundtrack that he or she is responsible for) in the arena of mega-budget films, where they can get approval to do custom recording halfway around the world, have unlimited ADR stage access, and be able to spend two or more days to perform the desired Foley cues per reel.

Conversely, there are craftspeople who can tackle and successfully develop and deliver a final soundtrack for ultra low-budget projects but who cannot structure, strategize, and oversee the sound supervisory responsibilities of mega-budget pictures.

Then there are those of us who move back and forth between huge budget jobs and tiny budget jobs at will. Over the years I have observed that those sound craftspeople who started their careers in a sound facility that was known for and specialized in big budget pictures usually had an extremely difficult time handling the “I ain't got no money, but we need a great soundtrack regardless” budget.

This is the realm of disciplined preplanning, knowing that it is vital to bring on a supervising sound editor before you even commence principal photography. This is where the triangle law we discussed in Chapter 4 regarding the rule of “you can either have it cheap, you can have it good, or you can have it fast,” really rises up and demands which two choices that all can live with.

Even if the producer is empowered by how important the soundtrack is to his or her project, the majority of first-time producers almost never understand how to achieve a powerful soundtrack for the audience, but they especially do not know or understand how to structure the postproduction budget and realistically schedule the post schedule.

This has given rise to the position commonly known as the postproduction supervisor, who, if you think about it, are really adjunct producers. Many of the postproduction supervisors that I have had the misfortune to work with do not know their gluteus maxim from a depression in the turf. With few exceptions, postproduction supervisors almost always just copied and pasted postproduction budgets and schedules from other projects that he or she thinks is about the same kind of film that he or she is presently working on. Virtually, without fail, these projects always have budget/schedule issues because every film project is different and every project needs to have its own needs customized accordingly. I have been called into more meetings where the completion bond company was about to decide whether or not to either shut the project down or take it over, and on more than one occasion their decision pivoted on what I warranted that I could or could not do in the postproduction process. By the way, this is an excellent example of why it is vital to always keep your word clean—do what you say you will do, and if you have trouble or extenuating circumstances to deal with do not try to hide it or evade it. Professionals can always handle the truth. I tell my people, “Never lie to me, tell me good news, tell me bad news—just tell me the truth. Professionals can problem solve how to deal with the issues at hand.”

YOU SUFFER FROM “YOU DON'T KNOW WHAT YOU DON'T KNOW!”

Every film project will tell you what it needs—if you know how to listen and do some basic research. You can really suffer from what I call, “You don't know what you don't know.” It can either make you or break you. Think about the following items to consider before you dare bid or structure a soundtrack on the ultra low-budget projects.

What genre is the film? Obviously a concept-heavy, science-fiction sound project is going to be more expensive to develop a soundtrack for than a film that is an intimate comedy-romance.

Read the script, highlighting all pieces of action, location, and other red flags that an experienced supervising sound editor has learned to identify, what will surely cost hard dollars.

Look up other projects that the producer has produced, noting the budget size that he or she seems to work in.

Look up other projects that the director has directed, and talk with the head re-recording mixer who ultimately mixed the sound and knows (better than any other person on that project) about the quality and expertise of preparation of the prior project.

Look up other projects that the picture editor has handled for the picture editing process. Look him or her up on IMDb (Internet Movie Database) and pick several pictures that are credited to them. Scroll down to the “sound Department” heading. Jot down the names of the supervising sound editor(s), especially the dialog editor. Without revealing the current project you are considering, ask these individuals about the picture editor; you will learn a wealth of knowledge, both pro and con, which is going to impact the tactical and political ground that you will be working with.

Case in point: When Wolfgang Petersen expanded his 1981 version of Das Boot into his “director's cut,” why did he not have Mike Le-Mare (who was nominated for two Academy Awards on the original 1981 version) and his team handle the sound editorial process? For those who understand the politics of the bloody battlefield of picture editorial, understand the potential of being undermined by the picture editor. You need to find out as much as you can about him or her, so you can navigate the land mines that you might inadvertently step on.

SOUND ADVICE

As the producer, you really need to engage the supervising sound editor and have him or her involved from the beginning if you are working on a fixed budget. A supervising sound editor will always have a list of recommended production sound mixers, not just name production sound mixers, but mixers who have a dependable track record of delivering good production sound on tough ultra low-budget projects.

If you think about it, that makes perfect sense. The supervising sound editor is going to inherit sound files from the very person he or she has recommended to the producer. When it comes to protecting your own reputation and an industry buzz that your word is your bond, then friendship or no friendship, when it comes to protecting your reputation and losing money on the project, then the supervising sound editor is going to want the best talent who understands what to get and what not to bother with under budgetary challenges.

I will not rehash what we have already discussed in Chapter 5—because the art form of what the production mixer will do does not change—only the choice of tools and knowing how to slim down the equipment costs and set protocols in order to save money.

When the supervising sound editor advises the producer on specific production sound mixers to consider, he or she will also go over the precise strategies of the production sound path—everything from the production sound recording on the set through picture editorial to locking the picture and the proper output of the EDL and OMF files, and of course, how to structure the post-sound editorial procedure. On ultra low-budget projects, it is vital that the producer understand the caveats of a fixed budget, so that the supervising sound editor can guarantee staying on budget and on schedule, as long as the “If …” clauses do not rise up to change the deal.

The “If” disclaimers can, and should, include everything from recording production sound a particular way, that proper back-ups are made of each day's shoot prior to leaving the hands of the production sound mixer. All format issues must be thoroughly discussed and agreed on, through the usage of sound (including temp FX or temp music) during the picture editorial process, then locking picture and handing it over to the supervising sound editor. The producer must be aware of what can and what cannot be done within the confines of the budget available.

With very few exceptions, projects that run into postproduction issues can be traced back to the fact that they did not have the expert advice of a veteran supervising sound editor from the beginning.

PRODUCTION SOUND

It is very rare to come across an ultra low-budget project that has the luxury of recording to a 4-track (or higher) recorder. You usually handle these types of production recordings in two ways.

1. You record to a sound recorder, whether the project is shot on film or shot on video, the production track is recorded on a 2-track recorder such as a DAT recorder or a 2-track direct-to-disk.

2. If the project is being shot on video, especially if in hi-def, the production sound mixer may opt to use only an audio mixer, such as the Shure mixer shown below. The output from the audio mixer is then recorded onto the video-tape, using the camera as the sound recorder, which also streamlines the log-and-capture process at picture editorial.

One decision you will have to think about if you are shooting video and you wish to opt for the production sound being recorded to the videotape, is whether the project set-ups are simple or highly complex. If the camera needs to move, enjoying more freedom will mean that you do not want a couple of 25-foot axle audio cables going from the sound mixer outputs into the back of the video camera's axle inputs. At the very least, this will distract the camera operator any time the camera needs to be as free as possible.

The best way to solve the cable issue is to connect the sound mixer outputs to a wireless transmitter. A wireless receiver is strapped to the camera rig with short pigtail axle connectors going into the rear of the camera.

Double Phantoming—The Audio Nightmare

Whether you opt for a cable connection from the sound mixer to the camera or if you opt to have a wireless system to the camera, the first most important thing to look out for is the nightmare of “double phantoming” the production recording.

Video cameras have built-in microphones. Any professional or semiprofessional video camera has XLR audio imports so that a higher degree of quality can be achieved. Because a lot of this work is done without the benefit of a separate audio mixer, these cameras can supply phantom power to the microphones.

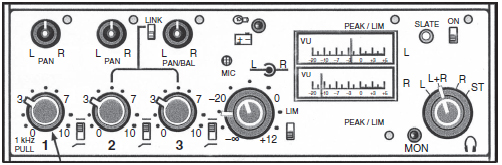

When the crew does have a dedicated production sound mixer, using an audio mixer, you must turn the phantom power option off in the video camera. The audio mixer, shown in Figure 14.1, has a LINE/MIC select switch under each XLR input. The audio mixer needs to send the phantom power to microphones—not the video camera, as the output becomes a LINE (not a microphone) issue.

If the video phantom power select is turned on, the camera will send phantom power in addition to the audio mixer, automatically causing a “double phantom” recording which will yield a distorted track. No matter how much you turn the volume down, the track will always sound distorted. The next law of audio physics is that sound once recorded “double phantomed” cannot be corrected, is useless, and can only serve as a guide track for massive amounts of ADR.

Using the Tone Generator

Different manufacturers have different means of generating a known line-up tone for the user. In the case of the Shure mixer (Figure 14.1), the first microphone input volume fader (on the far left) controls the tone generator. You simply pull the knob toward you, turning on the generator, creating a 1-kHz tone. Leaving the PAN setting straight up (in the 12 o'clock position) will send the 1-kHz signal equally to both channel 1 (left) and channel 2 (right). The center master fader can then be used to calibrate the outputs accordingly. Notice the icon just above the master fader that indicates that the inside volume control knob is used for channel 1 (left) and the outside volume control ring is used for channel 2 (right).

If you line up both channels together you will send the line-up tone out to the external recording device, e.g., the video camera or a 2-channel recorder such as a DAT.

Figure 14.1 The Shure FP33 3-Channel Stereo Mixer. This particular model is powered by two 9-volt batteries.

The production sound mixer coordinates with the camera operator to make sure that the signal is reaching the camera properly, that both channels read whatever -dB peak meter level equals “0” VU, such as -18 dB to as much as -24 dB, and that the recording device (whether it be an audio recorder or the video camera) has its phantom power option turned OFF. Once the recording device (audio recorder or video camera) has been set, only the production sound mixer will make volume changes.

The Pan Pot Controllers

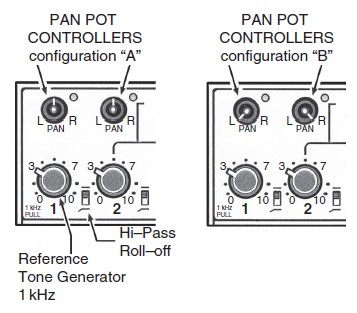

If you are using a single microphone, and wish to have both channels receiving the signal, then you should leave the Pan Pot Controller (above the microphone input volume fader being used) in the straight-up (12 o'clock) position, as shown in Figure 14.2 in configuration A.

If you are using two microphones and wish to have each channel kept in its own dedicated channel, then push in on the Pan Pot Controller knob. It will then spring out so you can turn it to either hard left or hard right. This will send microphone input 1 to channel 1 (left) only and microphone input 2 to channel 2 (right) only, as shown in configuration B. This does not necessarily make a stereophonic recording. Unless you set the microphones up properly in an X-Y pattern, or if using a stereo dual-capsule microphone, you will face potential phasing issues and no real disciplined stereophonic image. This configuration is best used if you have your boom operator using a boom mike and a wireless mike attached to an actor or two wireless mikes, one on each actor, or two boomed mikes that by necessity need to have the mikes placed far enough apart wherein one microphone could not properly capture the scene.

Also note in Figure 14.2 that there is a Flat/Hi-Pass setting option just to the right of each microphone input volume fader. Standard procedure is to record Flat, which means the selector would be pushed up to the flat line position.

Figure 14.2 The Pan Pot Controllers.

Figure 14.3 Two recording strategy set-ups.

If you really feel like you need to roll off some low end during the original recording, then you would push the selector down to the hi-pass icon position. Just remember, if you decide to make this equalization decision at this time, you will not have it later in postproduction. You may be denying some wonderful low-end whomps, thuds, or fullness of production sound effects. You must always record with the idea that we can always roll off any unwanted low-end rumbles later during the re-recording process, but you cannot restore it once you have chosen to roll it off.

Two Recording Strategies

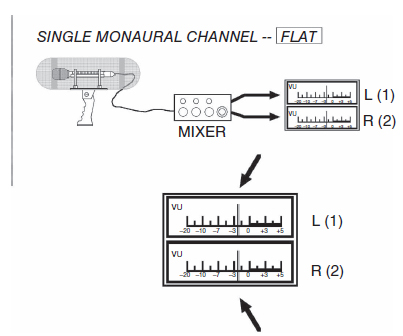

In Figure 14.3, “two channels independent” requires that the Pan Pot Controller above each microphone input volume fader be set to either hard left or hard right, depending on which channel the production sound mixer wants the signal to be sent. This is also the set-up setting you would want if you are recording stereophonically.

In Figure 14.3, “one channel—right channel -10 dB” requires that the Pan Pot Controllers above each microphone input volume fader be set to the straight-up (12 o'clock) position. This will send a single microphone input equally to the Master Fader—only you will note that after you have used the 1-kHz tone generator to calibrate the desired recording level coming out of the audio mixer to either the camera or to a recording device, you will then hold the inside volume control knob in place (so that the left channel will not change) while you turn the outside volume control ring counterclockwise, watching the VU meter closely until you have diminished the signal 10 dB less than channel 1. In the case of Figure 14.3, the left channel is reading -3 dB (VU), so you would set the left channel to -13 dB (VU). This is known as “right channel -10 dB,” which is used as a volume “insurance policy,” so to speak.

During the recording of a scene there may be some unexpected outburst, slam of a door, a scream following normal recording of dialog—anything that could over-modulate your primary channel (left). This becomes a priceless insurance policy during the postproduction editing process, where the dialog editor will only be using channel 1 (left), except when he or she comes upon such a dynamic moment that overloaded channel 1. The editor will then access that moment out of channel 2 (right) which should be all right due to being recorded -10 dB lower than the primary channel. Believe me, there have been countless examples where this technique has saved whole passages of a film from having to be stripped out and replaced with ADR. As you can see, this is a valuable technique on ultra low-budget projects.

Single Monaural Channel—Flat

Figure 14.4 shows a single microphone with both channels recording the same signal at the same volume. The Pan Pot Controller above the microphone input volume fader is set straight up to send the audio signal evenly to both left and right channels.

Figure 14.4 One microphone for both channels—FLAT.

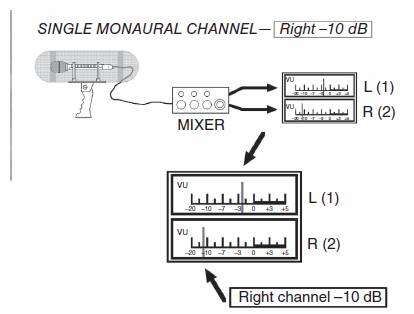

Single Monaural Channel—Right -10 dB

Figure 14.5 shows a single microphone. The Pan Pot Controller above the microphone input volume fader is set straight up to send the audio signal evenly to both left and right channels; however, the Master Audio Fader is set right channel -10 dB less than left channel.

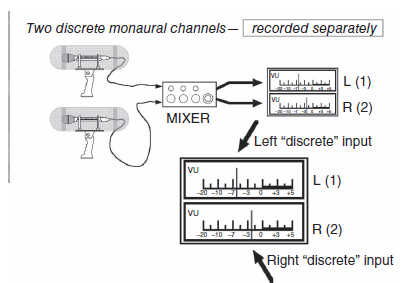

Two Discrete Monaural Channels—Recorded Separately

Figure 14.5 One microphone for both channels—channel 2 (right) set -10 dB from channel 1 (left).

Figure 14.6 Two discrete monaural channels.

Figure 14.6 shows two microphones with the Pan Pot configurations set to hard left and hard right, thus being able to use two different kinds of mikes. The production sound mixer must make precise notes on the sound report of what each channel is capturing, i.e., channel 1: boom mike, channel 2: wireless. The microphones do not have to be the same make and model, as this configuration is not for stereo use, but simply isolates two audio signals. The set-up could be that you have a boom operator favoring one side of the set where actor A is and a cable man, now acting as a boom operator, using a pistol-grip-mounted shotgun mike, hidden behind a couch deep in the set where he or she can better mike actor B, and so forth.

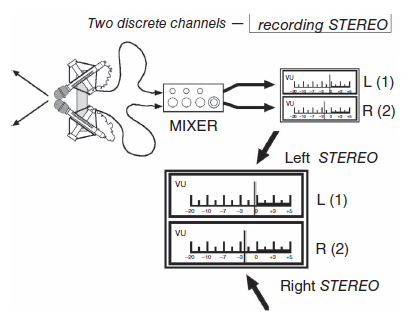

Two Discrete Channels—Recording Stereo

Figure 14.7 shows two microphones in an X-Y configuration, which greatly reduces phasing issues. The pan pot configurations are set to hard left and hard right. To record a correct stereophonic image both microphones must be identical.

The most dramatic phasing problems take place when an audio event, such as a car-by (as discussed in Chapter 10), causes a cancellation wink-out as the car (or performing item) crosses the center point, whereby the audio signal, which was reaching the closer microphone diaphragm a slight millisecond quicker than the far microphone, is now going to reach the second microphone diaphragm before it reaches the first one. This center point area of crossing over is where the phasing cancellation wink-out area comes into play. If the two channels are folded together, which often happens somewhere in the postproduction process and certainly will be noticed if it is televised and the stereo channels are combined in a mono playback option, there will be a drop-out at the center point. This is why you want the two diaphragms as close together as possible.

Notice in the Schoeps X-Y configuration, the microphone capsules are actually over/under, getting the two diaphragms as close as possible to zero point.

Figure 14.7 Stereophonic recording using X-Y microphone configuration.

SOUND EDITING STRATEGIES

Budget restrictions should only compel you to rethink how you will get your arms around the soundtrack. I have heard too many editors slough it off as, “I'm not going to give them what they're not paying for.” I suppose that kind of attitude makes one feel better about not having a budget to work with—but it backfires on you, because when all is said and done nobody will (A) remember, (B) have knowledge of, or (C) give a damn what the budget and schedule restrictions were. Your work is up there on the screen—and that is all that matters.

You must know how to cut corners without compromising the ultimate quality of the final soundtrack. This is where veteran experience pays off. Some of the best supervising sound editors in features today learned their craft by working in television, a medium that always was tight and fast. It is far more difficult for an editor who only knows how to edit big feature style to shift gears into a tight and lean working style.

You have to learn how to work within the confines of the budget and redesign your strategies accordingly. The first thing you have to decide is how to do the work with a very tight crew. Personally, I really learned how to cut dialog by working on the last season of Hawaii 5-O, where they would not allow us to ADR anything. We had to make the production track work and we did a show every week!

I have developed a personal relationship with several colleagues, each with his or her own specialty. When we contract for a low-budget project, we automatically know that it is a three-person key crew. I handle the sound effect design/editing as well as stereo backgrounds for the entire project; Dwayne Avery handles all the dialog editing, including ADR and Group Walla editing; and our third crewmember is the re-recording mixer Zach Seivers in North Hollywood. The only additional talent will be the Foley artist(s), and the extent of the Foley work will be directly linked to how low an ultra low-budget project can afford. Vanessa Ament, a lead Foley artist/supervisor, put it this way:

Sometimes I think Foley artists and Foley editors lose sight of what Foley is best used for. There is a tendency to “fall in love” with all the fun and challenge of doing the work, and forgetting that edited sound effects are going to be in the track also. Thus, artists and editors put in sounds already covered by effects. The problem with this is three-fold. First, the sound effects editor can pull certain effects faster out of the library or cut in recorded field effects that are more appropriate without the limitations of the stage. Second, the Foley stage is a more expensive place to create effects than the editing room, and third, the final dubbing mixer is stuck with too many sounds to sort through. I remember a story about a very well respected dubbing mixer who was confronted with 48 tracks of Foley for a film and in front of the editor, tore up the pages with tracks 25 through 48, tossed them behind him and requested that tracks 1 through 24 of Foley be put up for pre-dubbing. The lesson here is: think of the people who come after you in the chain of filmmaking after you have finished your part.

Figure 14.8 Vanessa Ament, lead Foley artist, performing props for Chain Reaction. The Foley artist assisting her is Rick Partlow. (Photo by David Yewdall.)

On Carl Franklin's One False Move, Vanessa Ament only had two days to perform the Foley, because that was all the budget could afford. It was absolutely vital that Vanessa and I discuss what she absolutely had to get for us and what cues she should not even worry about, because I knew that I could make them myself in wild recordings or I had something I could pull from the sound effect library. And that is really the key issue—Foley what you absolutely have to have done. If your Foley artist has covered the project of all the have-to-get cues and there is any time left over, then go back and start to do the B list cues until your available time is up. You have to look at it as how full the glass is, not how empty it is.

For the dialog editor, it becomes a must to work with OMF, which means that the assistant picture editor(s) had to do their work correctly and cleanly. As I have said before, “junk-in, junk-out.” If the dialog editor finds that a reprint does not A-B compare with the OMF output audio file identically, then you are in deep trouble. If you cannot rely on the quality of the picture editorial digitizing process, then you are going to have to confront the producer with one of the “If” disclaimers that has to affect your editorial costs. “If” you cannot use the OMF, and the dialog editor has to reprint and phase match, there is no way you can do the editing job on the same low-cost budget track that you are being asked to work with.

I have seen this “If” rise up so many times that I really wish that producers have to be required to hire professional experts who really know the pitfalls and disciplines of digitizing the log-and-capture phase of picture editorial. So many times, producers hire cheap learn-on-the-job interns to do this work because they save a lot of money— only to be confronted in postproduction with the fact that they will be spending many times as much to fix it as it would have cost to do it right the first time.

It is also at this stage of the project that you really understand how valuable a good production sound mixer who understands the needs and requirements of post-production is to an ultra low-budget project. He or she will understand to grab an actor who has just a few lines as bit parts, and on the side, record wild tracks of them saying the same lines with different inflections, making sure that their performance is free and clear of the noise that constantly plagues a location shoot.

Figure 14.9 Clancy Troutman oversees the progress of his sound designer, Scott Westley, at Digital Dreams in Burbank, CA. (Photo by John LeBlanc.)

I cannot tell you how much the production sound mixer Lee Howell has saved his producer clients by understanding this seemingly simple concept of wild tracks of location ambiences and sound reports with lots of notations about content. Precise notes showing the wild tracks of bit players will save a producer from flying in actors for ADR sessions just to redo a handful of lines. It becomes the fast track road map to where the good stuff is.

Good production track is pure gold—literally worth gold when you do not have a budget to do a lot of ADR or weeks and weeks of dialog editors to fix tracks.

I can always tell the amateur dialog editor. His or her tracks are all over the place, with umpteen tracks. You must prepare your dialog with ambience fills that make smooth transitions across three or four primary tracks, not including P-FX and X-tracks (you will read about dialog strategy in Chapter 15).

Have your director review a ready-to-mix dialog session, not during the mix, but with the dialog editor, making his or her choices of alternate performances then and there, rather than wasting valuable mixing time deciding which alternate readings he or she would prefer.

Not all supervising sound editors, or for that matter, sound editors who support the supervisor's strategies can shift from meg-budget projects to ultra low-budget projects with a clear understanding of the art form and the necessary strategies to tackle either extreme without waste or confusion. Clancy Troutman, the chief sound supervisor for Digital Dreams Sound Studios located in Burbank, California, has worked on projects that challenge such an understanding.

Clancy is a second-generation sound supervisor, learning his craft and the disciplines of the art form first as an apprentice to and then as a collaborator with his father, Jim Troutman, veteran of several hundred feature films. Jim's vast experience, knowledge of sound, creativity, and expertise have teamed him over the years with some of Hollywood's legendary directors, including Steven Spielberg, Mel Brooks, Peter Bogdanovich, and Sam Peckinpah. Clancy worked under his father on sound designing and sound editing for Osterman Weekend, Life Stinks, The Bad Lieutenant, Fast Times at Ridgemont High, and Urban Cowboy.

Clancy came into his own, stepping into the supervising sound editor position with such projects as Beastmaster, Cop with James Woods, Cohen & Tate with Roy Scheider. Other challenging projects include supervising the sound for Police Academy: Mission to Moscow, Hatchet, Pentagon Papers, and the Toolbox Murders, to name just a few.

His work on Murder She Wrote, China Beach, and Thirtysomething honed his skills in the world of television demands and challenges, earning him the supervising sound editor chores for the popular cult television series The Adventures of Brisco County Jr., starring Bruce Campbell.

This eclectic mix of product has given Clancy the understanding how to shift back and forth between traditional budgets and schedules to ultra low-budget strategies. Even though Clancy has amassed one of the largest sound effect libraries in the business, he really believes in the magic and value of the production sound recordings captured on location.

Collaborating with clients to yield as much bang for the buck as possible has been both Clancy's challenge and ultimate satisfaction with problem solving the project at hand. He loves to design and create a unique sound experience for the film that, for the present, only lives in the client's imagination.

THE EVOLUTION BLENDING OF EDITOR AND RE-RECORDING MIXER

Those of you who have not been part of the film and television sound industry for at least the last 25 years cannot truly understand why the things have worked the way they have and why there is so much resistance to the evolution of the sound editor and the re-recording mixer moving closer together and becoming one and the same.

The traditional re-recording community struggles to remain a closed “boys club”— this is no secret. Since the days when the head re-recording mixer (usually handling the center chair or dialog chores) literally reigned as king on the re-recording stage, he could throw out anything he wanted to. Many a reel got “bounced” off the stage because the head mixer did not like how it was prepared or did not care for the sound effect choices. Mixers often dictated what sounds were to be used, not the sound editor.

Even when I started supervising sound shows in the late 1970s, we would see and sometimes be a part of butting heads with the head mixer who ruled the stage and held court. The major studios were not the battleground where change was going to take place. It took independent talents such as Walter Murch and Ben Burtt, who had the directorial/producerial leadership to give them their freedom.

I remember how stunned I was when I was supervising the sound for John Carpenter's The Thing. We were making a temp mix for a test audience screening. The Universal sound department was already upset that one of their pictures was not going to be left to Universal sound editors and that ADR and Foley chores would not use Universal sound facilities, but worst of all, the final re-recording mix was going to be across town at Goldwyn.

I could write an entire book on postproduction politics and the invisible mine field of who controls what, and when you should check that stinging sensation in your back that might be something more than just a bad itch.

We no sooner got through the first 200 feet of reel 1 when I put my hand up to stop. The head re-recording mixer did not stop the film. I stood up, with my hand up—“Hold it!” The film did not stop. I had to walk around the end of the console, step up on the raised platform, and as I paced toward the head mixer, he hit the STOP button, stood up, and faced me square on. “What seems to be the problem?”

Then I made one of the greatest verbal goofs, the worst thing that I could possibly have said to a studio sound mixer: “You're not mixing the sound the way I designed it.”

Snickers crossed the console, as the head mixer stood face-to-face with me, holding back laughter. “Oh, boys—we are not mixing the film the way Mister Yewdall has designed it.”

He started to tell me that he was the head mixer and by god he would mix the film the way he saw fit, not the way I so-called designed it.

Naturally, I had a problem with that. We stood inches apart and I knew that this was not just a passing disagreement. This was going to be a defining moment. I knew that the Universal crews were upset that they were not doing the final mix; I knew that the temp mix was a bone thrown to them so they were not completely shut out of the process. John Carpenter had mixed all his films with Bill Varney, Gregg Landaker, and Steve Maslow over at Goldwyn Studios in Dolby stereo, and he certainly intended that The Thing was also going to be mixed by his favorite crew—the political battle was rumbling like a cauldron.

I informed the head mixer that he was going to mix the film exactly as I had conceived it, because I had been hired by John Carpenter a year before principal photography had even started developing the strategies and tactics of how to successfully achieve the soundtrack that I knew John wanted. John wanted my kind of sound for his picture, and I owed my talent and industry to John Carpenter, not to studio political game playing. To make matters worse, Universal Studios did not want the film to be mixed in Dolby stereo, saying that they did not trust the matrixing. They said it was too undependable, and boy, that took an amazing knockdown, drag-out battle royal late one night in the “black tower” with all sides coming to final blows.

So, now I stood there, eyeball-to-eyeball with the head mixer, knowing I did not dare flinch. He then made a mistake of his own, when he said, “Maybe we should get Verna Fields involved in this decision.” (Verna Fields was, at that time, president of production for Universal Studios.)

I agreed. And before he could speak I told the music mixer her telephone extension. I could tell from the head mixer's eyes that he was caught off guard that I even knew her number. But, we literally stood there like statues, staring at each other with total resolve while Verna Fields left the Producers Building, paced past the commissary, and into the sound facility.

I didn't even have to look; I recognized the sound of her dress as she stormed into the room. Those of you who have had the honor of knowing Verna know exactly what I am talking about; those of you who don't missed out on arguably the most powerful woman Hollywood has ever known, certainly one of the most respected.

“What seems to be the problem here?!” she demanded.

The head mixer thought he was going to have a lot of fun watching Verna Fields rip a young whippersnapper to ribbons. With a sly smirk he replied, “I don't have a problem, but it seems Mister Yewdall does.”

Verna was in no mood for games. “And that is?”

I kept my eyes locked onto the head mixer, for to look away now would be a fatal mistake. “I told your head mixer that he is not mixing this film the way I designed the sound.”

The head mixer was doing everything to contain himself. He just knew that the “design” word was going to really end up ripping me to pieces, and with any luck, I would get fired from the picture.

Instead, Verna's stern and commanding voice spoke with absolute authority. “We are paying Mister Yewdall a great deal of money to supervise and design the sound for this motion picture—and you will mix it exactly as he tells you.”

If I had hit the head mixer with a baseball bat, it would not have had as profound an effect. It was as if a needle had popped a balloon, or you had just discovered your lover in bed with somebody else! I still did not turn to her. I actually felt sorry for the head mixer for how hard it had hit him.

“Are there any other issues we need to discuss?!” demanded Verna.

The head mixer shook his head weakly and turned back to his chair. I turned to see Verna; her thick Coke-bottle glasses magnified the look in her eyes. I nodded my thanks to her as she turned to leave.

Independent sound mixing had gone on for some time, but not on the major studio lots. By noon it was all around town. The knife had cleanly severed the cord that the head mixer ruled as king. The role of the supervising sound editor suddenly took a huge step forward. The unions tried to fight this evolution, for as long as we were working on 35-mm stripe and fullcoat, they could keep somewhat of a grip on it. But when editors started to work on 24-track 2” tape, interlocking videotape to time code, the cracks were starting to widen. It was clear that the technological evolution was going to rewrite who was going to design and cut and re-record the soundtrack. Union 695 actually walked into my shop a few months later with chains and a padlock, citing that I was in violation of union regs by having a transfer operation, which clearly fell under Union 695 jurisdiction.

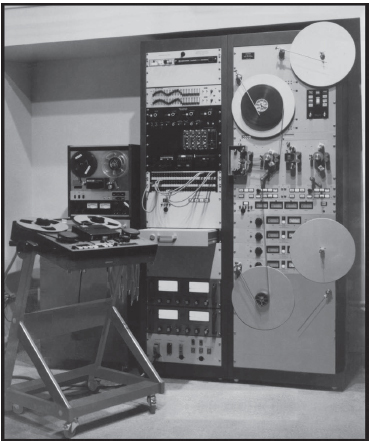

I asked them what made them think so. They marched back to my transfer bay (Figure 14.10) and recited union regs that Union 700 editors could not do this kind of work. I corrected them by pointing to John Evans, who was my Union 695 transfer operator.

The first union man pointed to the left part of the array, where the various signal processing gear was racked. “His union status doesn't allow him to use that gear.”

“He doesn't,” I replied.

“Then who DOES?!” he snapped back.

“I do.”

The union guy really thought he had me. “Ah-Ha! You're an editor, not a Y-1 mixer!” He started to lift his chains.

“Excuse me,” I interrupted. “I know something about the law, gentlemen. Corporate law transcends union law in this case. I am the corporate owner, and as a corporate owner I can do any damn thing I want to. If I want to be a director of cinematography on a show I might produce, I can do that—and the union cannot do one thing to stop me.” I pointed to John Evans. “You see, only he uses his side of the rack; when the signal processing gear is utilized, I am the one who does that.”

Figure 14.10 David Yewdall's transfer bay, designed and built by John Mosley.

I noticed that the second union man had drifted back and grabbed the phone; I supposed to call the main office. He came back and tapped his buddy on the arm—they needed to leave.

A couple of days later the two men returned (without chains and a padlock) and asked if I would like a Y-1 union card. “Gee, why didn't you ask me that before?”

More and more of my colleagues were going through this process, carrying dual union cards. Alan Splet is a perfect example. Alan was David Lynch's favorite sound designer, having helmed Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune, and Blue Velvet. On Dune, Alan even served as the fourth re-recording mixer on the console with Bill Varney, Gregg Landaker, and Steve Maslow on Stage D at Goldwyn. Alan's work was truly an art form. His eyesight was very poor (I often had to drive him home late at night when the bus route stopped running), but what a pair of ears he had and what an imagination. His work was wonderfully eclectic, supervising and sound designing films such as The Mosquito Coast, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Poets Society, Mountains of the Moon, Wind, and of course, the film he won the Academy Award for, Black Stallion.

I remember him literally having a 35-mm transfer machine to his left; he would play his ¼” sound masters through an array of sound signal equipment to custom transfer each piece of mag film as he needed it. He would break it off, turn to his Moviola, lace it up, and sync it to picture. This was an extremely rare technique (and often a luxury)—but it was the key to his designing the kind of audio events he wanted. But this kind of trust takes a director and/or producer to back your play.

Then nonlinear editing became the new promise of lower budgets, faster schedules, and better sound. We have already spoken about the philosophy and collateral cost issues, so I will not rehash that. It scared the bejesus out of hundreds of veteran sound editors, many who felt that they could not make the transition and dropped out of the industry.

For a while it was really only an issue for editors, but it soon became apparent to the re-recording mixers that it was going to affect them in a huge way. Even today, many mixers are scrambling to compete with, learn, and embrace Pro Tools as an end-all. Those who only thought Pro Tools was only for editing were not understanding the entire process—and now it is here. More and more projects are no longer being mixed at the traditional houses, because these projects are being completely edited, re-recorded, and print-mastered with Pro Tools.

Is it as good as mixing at the traditional stages? I didn't say that. What I think philosophically does not mean a thing. It is a reality of the evolutionary process that big multi-million-dollar re-recording mix stages will only be used for the big pictures, and virtually everything else is going to be done, at least in part, if not totally through the computer, using software and a control mix surface by one- or two-man mixing crews, often by those who supervised and prepared the tracks in the first place.

THINK BIG—CUT TIGHT

One of the first things you are going to do, in order to capture the Big Sound on a tiny budget, are crash-downs, pre-predubs, all kinds of little maneuvers to streamline how you can cut faster.

In the traditional world I had 10 stereo pairs of sound effects just for a hydraulic door opening for Starship Troopers. When I handled the sound effects for Fortress II, they could not afford a big budget, but they wanted my kind of sound. I agreed to design and cut all the sound effects and backgrounds for the film on a flat fixed fee. The deal was that you could not hang over my shoulder every day. You can come Friday afternoons after lunch and I will review what I have done. You make your notes and suggestions and then you leave and I will see you a week later.

The other odd request I made in order to close the deal, since I knew how bad they wanted my kind of sound, was that I could use some wine, you know, to help soften the long hours. I had meant it as a joke. But, sure enough, every so often I had deliveries of plenty of Zinfandel delivered to my cutting room. Actually, in retrospect, the afternoons were quite—creative.

One of the requests that they did ask of me was that they really wanted space doors that had not been heard before. So I designed all the space doors from scratch, but I couldn't end up with dozens of tracks with umpteen elements for these doors every time they would open and close, not on an ultra low-budget job. So I created a concept session. Anything and everything that the client may want to audition as concept sound that was going to have an ongoing influence in the film—from background concepts, to hard effects, laser fire, telemetry, etc. I designed the doors in their umpteen elements, played them for the client on Friday for approval. Then I mixed each door down to one stereo pair, which became part of my sound palette—a term I use to mean the sound kit for that particular show.

I will use the same procedure in creating my palette for anything and everything that repeats itself. Gunshot combos, fist punch combos, falls—mechanicals, a myriad of audio events that I used to lay out dozens of tracks for the sound effect re-recording mixer to meticulously rehearse and mix together in the traditional process— was being done now in sound effect palettes or what some editors call “show kits,” especially if they are working on television shows that repeat the basic stuff week after week. Don't reinvent the wheel, build your kit and make it easier to blaze through the material.

It might take me a week or two to design and build my sound palette, but once built, I could cut through heavy action reels very quickly, with a narrow use of tracks. Instead of needing as many as 200 or 300 tracks for a heavy space opera sequence, I could deliver two at the most three 24-track sessions, carefully dividing up the audio concepts in the proper groups. This made the final mixing much smoother. This style of planning also allows you to cut the entire show, not just a few reels of it, as we used to do on major projects with large sound editorial teams.

I have even gotten to the point that I back up every show in its show kit form. I have a whole series of disks of just the Starship Troopers effects palette, which is also why I can retrieve a Pro Tools session icon from a storage disk, load up the Starship Troopers disks, and resurrect any session I made. This sort of thing can come in extremely handy down the road when a studio wants to do some kind of variation edit, director's cut, or what have you. More than once I have been called by a desperate producer who has prayed that I archived my work on his film, as the studio cannot find the elements.

Strange as it might sound, but I have had more fun and freedom in sound design working on smaller budget pictures than huge budget films that are often burdened with political pressure issues and crunched schedule demands.

KEEP IT TIGHT—KEEP IT LEAN

The reality of your team is that you will find yourself doing most if not all your own assistant work. Jobs that were originally assigned to the first assistant sound editor are now done by the dialog editor or the sound effects editor or the Foley editor (if you can afford to have a Foley editor).

I very quickly found that hiring an expert consultant on a daily basis was a valuable procedure. Ultra low-budget jobs are almost always structured on a fixed flat fee, not including “If” factors. This means that you cannot afford to make a financial mistake by doing work on a bad EDL or wasting time going back to have the OMF re-outputted because picture editorial did not do it right the first time.

Figure 14.11 Typical ultra low-budget crew.

In the last few years I have been working rather successfully with the 3- to 4-man crew system. A client will talk to us about a project, and if we like it and feel we can do it within the tight parameters, we will sit down and discuss exactly what kind of time frame the client will allow, as more time makes it more realistic to be accomplished. If the client insists on too tight a schedule, the client either needs to come up with more money, because they have chosen the other set of the triangle (want it good and want it fast, therefore it cannot be cheap).

If they have to have it cheap, then they have to give you more time, because we already know they want to have it good. Besides, I am interested in turning out only good work, so that option is always on the table.

Several projects that I have done lately have been structured as depicted in Figure 14.11. It is vital to have a veteran dialog editor, a master on how to structure and smooth the tracks. Though I have cut my share of dialog, I am known for my sound effect design, especially action and concept, so I take on the sound design and sound editing chores for the backgrounds and hard FX. We use a lead Foley artist who also embraces the job of cueing the show as well as performing the action. The budget is a direct reflection of how many days of Foley walking the project can afford. I go over the show notes and make it very clear to the Foley artist exactly what cues we absolutely have to have performed and what cues I can either pull from my library or custom record on our own. This keeps the Foley stage time to the leanest minimum with as little waste as possible.

You notice that I have the re-recording mixer to my side, an equal in the collaboration of developing and carrying out the ultimate re-recording process. On several projects, the re-recording mixer doubled as the ADR supervisor, scheduling the actors to come in and be recorded. The ADR cues, however, are sent back with the stage notes for the dialog editor to include in a separate set of tracks, but part of the dialog session. This will yield a dialog session with probably 3 to 4 primary dialog tracks, with 4 to 5 ADR tracks (depending on density) and then the P-FX and X-Track. This means the dialog session that will be turned over to the re-recording mixer should be 10 to no more than 14 tracks.

The key to really being able to give big bang for the buck is if you have a powerful customized library. This is where most starting editors have a hard time. Off-the-shelf libraries are, for the most part, extremely inferior to those of us who have customized our sound libraries over the last 30 years. I always get a tickle when my graduate editors, who have frankly gotten spoiled with using my sound effects during their third and fourth year films, go out into the world and sooner or later get back to me and tell me how awful the sound libraries are that are out there. Well, it's part of why I push them, as well as you, the reader, to custom record your own sound as much as possible.

Even if you manage to get your hands on a sizeable library from somewhere, there is the physicality of knowing it. Having a library does not mean anything if you have not auditioned every cue, know every possibility, every strength, every weakness. It takes years to get to know a library, whether you build it yourself or work with a library at another sound house.

You need to spend untold hours and hours, going through material, really listening. You see, most people do not know how to really listen. You have to train your ear, you have to be able to discern the slightest differences, detect the edgy fuzziness of oncoming distortion.

I will cut one A session; this will be “Hard FX.” Unlike traditional editing when I break events out into A-FX and B-FX and C-FX and so forth, I will group the controlled event groups together, but they are still in the same session. After all, we do not have all the time in the world to re-record this soundtrack. Remember, we are making the perception of the Big Sound, not the physical reality of it.

I will cut a second B session. This will be my stereo background pass. Remember my philosophy about backgrounds: dialog will come and go, music cues will come and go, Hard FX will come and go, but backgrounds are heard all the time, even if extremely subtle. The stereophonic envelope of the ambience is crucial, and I give it the utmost attention.

On an ultra low-budget project like this, I expect 8 Foley tracks will be about as much as we can expect, unless we have to suddenly go to extra tracks for mass activity on the screen. Even then, I do not want to spread too wide.

The best rule of thumb is to prepare the tracks in a way that you yourself could re-record them the easiest.

RETHINKING THE CREATIVE CONTINUITY

Speaking of intelligently approaching soundtrack design, here is another important consideration—what if you are not preparing it for the re-recording mixer(s) to get their arms around? What if, on small budget or bigger budget projects, the supervising sound editor/sound designer is also serving as the re-recording mixer?

Figure 14.12 Mark Mangini, sound designer/supervising sound editor/ re-recording mixer.

Actually, it makes sense in a big way, if you stop to think about it. Since the advent of the soundtrack for film in 1927, the approach has been a team of sound craftspeople, each doing his or her part of the process. When it reached the re-recording mixing stage, the re-recording mixer had no intimate knowledge of either the preparation or the tactical layout and the whys of how certain tracks were going to work with other tracks or what the editors had prepared that was yet to come to the stage in the form of backgrounds that would serve both as creative ambient statements and/or audio bandages that were there to serve camouflaging poor production recording issues. That process occurred because working on optical sound technology made it impossible for one sound craftsperson to record production dialog (on optical sound cameras)—and then follow the process through the various disciplines of sound editing, and then ultimately be the re-recording mixer. Even in 1953, when we moved to magnetic stripe/ fullcoat film technology, the process still required a platoon of expert audio crafts people to properly record, transfer dailies and reprints, design, and edit sound in strategic groupings before it could be brought to the re-recording stage for the head re-recording mixer to bring it all together.

However, with today's digital software tools and ever-expanding capacities of storage drive space and faster CPUs, a single sound craftsperson can do the same work that it took 10 or 12 craftspeople to do a decade ago.

Who better would know the material? Not the re-recording mixer who was not involved in the sound designing process, the editing of that material, or structuring the predub strategies. So, you see it really makes sense that we are starting to see and are going to see a major move to very tight teams, and in some cases single sound designer/re-recording mixer artists.

One such advocate of this move is Mark Mangini, truly a supervising sound editor/sound designer and re-recording mixer. As a supervising sound editor/sound designer he has helmed such feature projects as Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, Gremlins, Lethal Weapon 4, The Fifth Element, The Green Mile, The Time Machine, and 16 Blocks.

Recently he was troubled by the decision of a producer who shunned the idea of the sound supervisor/sound designer also being the re-recording mixer, as it is the exception and certainly not the norm. Here, then, are the words of Mark Mangini when he decided he needed to write the producer and put his thoughts down for the record, thoughts that make a lot of sense—the logic of an inevitable evolution.

On the Importance of Designing and Mixing a Film

A letter from sound designer Mark Mangini to the director of a big-budget studio film:

It is my desire to design, edit, and mix your film. Though the Producer and the editor are very well intentioned in wanting to use the Studio's mix facilities with existing mixers there, they do have some very fine people. I believe that I can bring so much more to the film as the Sound Designer and Mixer, as I have done on your previous projects.

I must state at the outset that, for a studio film, this style of working is non-traditional and, as such, will encounter some amount of resistance from your fellow filmmakers accustomed to working in traditional ways (designers only design, editors only edit, and mixers only mix).

This way of working is non-traditional because of the natural and historical compart-mentalization of job responsibilities in every aspect of filmmaking, not just sound. As such, very few individuals have taken the time or had the incentive, like myself, to develop natural outgrowths of their skill-set and be proficient in multiple disciplines.

I am certainly not the first to work this way. Walter Murch, Gary Rydstrom, Ben Burtt, to name a few, come to mind and have all been championing the benefits of the sound designer in its broadest interpretation and what that person can bring creatively to a soundtrack. These men have truly been the authors of their respective soundtracks and they are successful at it by virtue of being responsible for and creatively active in all aspects of sound for their films. This does not simply include being the sound editor and the re-recording mixer but encompasses every aspect of sound production including Production sound, ADR, Foley, Score recording, sound design and editing, and mixing.

As you have seen in our past work relationship, I have performed in exactly this fashion and I hope that you have recognized the benefits of having one individual whom you can turn to creatively and technically to insure the highest quality soundtrack possible in all the disciplines. This is the way I work and want to continue to work with you.

Though it may appear that this workflow was necessitated by budget (or lack thereof) on our previous films, it was and is, in fact, a premeditated approach that I believe is the most creative and efficient way of working. Just imagine how far we can take this concept with the resources that the Studio is offering.

Unfortunately, Hollywood has not “cottoned” to this approach in the way that Bay Area filmmakers have. We still want to pigeonhole sound people by an antiquated set of job descriptions that fly in the face of modern technology and advancement. It is certainly not rare or unheard of in the production community to see hyphenate “creatives” that write and direct, that act and produce, etc.—it is no different in sound. I am simply one of a small group of sound fanatics that wants to work in multiple disciplines and have spent a good deal of time developing the technical acumen in each one.

As such, regarding making “all the super-cool decisions that will give me the most creative and technically etc… .

I have no doubts that this is the way to do it. There are decided creative, technical and financial advantages to working this way. This work method is not, in fact, all that unusual for the Studio or the mix room we anticipate using. There have been numerous films that have mixed there that are working in this exact same fashion. New yes, but not unheard of.

As we spoke of on the phone, I will be working side by side with you, building the track together in a design/mix room adjacent to picture editorial. In the work flow that I am proposing this is a very natural and efficient process of refinement all the way through to the final mix that is predicated on my ability to mix the track we have been building together and on doing it in at the Studio's dub stage, which uses state of the art technology NOT found in any of the other mix rooms on the lot (and with traditional mixers that are not versed in how to use it).

The value of having the Sound Design team behind the console cannot be overestimated. It seems to me almost self-evident that having the individuals who designed and edited the material at the console will bring the most informed approach by virtue of an intimate knowledge of every perforation of sound present at the console and the reasons why those sounds are there. This is a natural outgrowth of the collaboration process that we will share in during our exploratory phase of work as we build the track together prior to the mix.

There will be the obvious and natural objections from less forward thinking individuals who will state that having the sound editors mix their own material is asking for trouble. “They'll mix the sound effects too loud” or “They won't play the score” are many of the uninformed refrains that you might hear as objections to working in this fashion.

I would like to think that, based on our previous work together, you might immediately dispel these concerns having seen, first-hand, how I work but there is also an issue of professionalism involved that is never considered: This is what I do for a living. I cannot afford to alienate any filmmaker with ham-fisted or self-interest driven mixing.

I consider you a good friend and colleague. As such, I think you know that I am saying this from a desire to make your film sound as great as I possibly can. It's the ones that think outside the box that do re-invent the wheel.

Sincerely,

- Mark Mangini, sound designer/supervising sound editor/re-recording mixer (Note: This is a letter I wrote to a director, regarding a big-budget studio film I was keen on doing. I have modified the original text to make the ideas and comments not project specific and more universal. MM)

DON'T FORGET THE M&E

Just because you are tackling an ultra low-budget project does not mean that you do not have to worry about the inventory that has to be turned over just as in any film, multi-million dollar or fifty thousand dollars. The truth of the matter is, passing QC (quality control) and an approved M&E (music and effects) is, in many ways, more difficult to accomplish on ultra low-budget films than on big budget films, for the simple fact that you do not have extra money and manpower to throw at the problem. It therefore behooves you to have a veteran dialog editor who is a master of preparing P-FX tracks as he or she goes along. (We will talk about this more in Chapter 15.)

You are really going to have to watch how much coverage you have in Foley today. For some reason, the studios and distributors have gone crazy, demanding over-Foley performing of material. I mean stupid cues like footsteps across the street that you would never hear; the track can be written up for missing footsteps. I have heard some pretty interesting horror stories, and frankly, I do not know why. I assume it is an ignorance factor somewhere up the line. When in doubt—cover it.

AN EXAMPLE OF ULTRA LOW-BUDGET PROBLEM SOLVING

Just because you do not have a budget does not mean that you cannot problem solve how to achieve superior results. I recently received an e-mail from a young man, Tom Knight, who was just finishing an ultra low-budget film that was shot in and around London. I was impressed that the lack of a budget did not inhibit the team's dedication to achieve the best audio track that they could record during a challenging production environment as well as the postproduction process. Tom submitted the following details on the project and their approach to problem solve some of the audio hurdles:

Figure 14.13 This set-up was for recording an impulse response for a convolution reverb (London). Equipment: Mac iBook running Pro Tools LE, M-Box, Technics Amp, Alesis Monitor One MKII, AKG 414. (Photo by Tom Knight.)

The film's title is Car-Jack, an original production, written, produced, and directed by George Swift. I was responsible for all the audio production within the film including original music, location recording, postproduction and mixing.

George approached me about the film because I had worked for him on a short animation the previous year. We were both studying for BAs at the time in our respective subjects and stayed on to study for master's degrees.

The 40-minute film about a gang of car-jackers was produced for virtually no budget (less than £1,000), even though there was a cast and crew of over 50 people. Everyone worked on the project for free because they believed in the film, which ensured a great spirit on set. We were fortunate enough to have access to the equipment we needed without hire charges from the university (Thames Valley University in Ealing, London).

The film was predominantly shot on a Sony Z1 Hi-Def camera and cut digitally using Adobe Premiere. The production audio was recorded onto DAT and cut at my home studio with Pro Tools before being mixed in the pro studios at Uni.

When we filmed indoor locations, I made sure that I went equipped with a laptop (including M-Box), amp, and speaker so that I could record impulse responses. This process involves playing a sine sweep that covers every frequency from 20 Hz to 20 kHz through a speaker, and recording the outputted signal back onto disk through a microphone.

The original sweep can then be removed from the recorded signal, which leaves the sound of the room or space that the recording was made in. Convolution reverbs like Logic's Space Designer can take an impulse recording and then make a fairly accurate representation of the acoustical space back in the studio. This is ideal if you intend to mix lines of production dialogue with lines of ADR, because you need the sounds to have similar acoustic properties, so that they blend together and create the impression that they were recorded at the same time.

Figure 14.14 Set-up for recording the impulse response for a convolution reverb, same process as above but from the reverse. This part of the room was where the main gang boss character conducted his meetings so it made sense to take the impulse from here. (Photo by Tom Knight.)

Figure 14.15 Rooftop scene from the film (London). Equipment: Sony Z1 Camera shooting in hi-def, Audio-Technica AT897 Shotgun + DPA Condenser mikes running through a Mackie 1202-VLZ Mixer onto DAT. Cast and crew (left to right): Annabelle Munro (lead actress), Tony Streeter (lead actor), David Scott (cinematographer), George Swift (director), Tom Knight (boom operator/sound mixer). (Photo by Julia Kristofik, make-up artist.)

Figure 14.15 shows us setting up the shot before we go for a take. If you look closely under the actress's left hand you can see some tape on the wall. This is where the DPA mike is positioned. The reason it is positioned there is because Heathrow Airport is only 2 miles away and that particular day the planes were taking off straight towards us, and then alternately banking either left or right as you see this picture. Placing it there (rather than on the jacket of the actor) meant that the wall shielded it to some extent from planes that banked left which were heavily picked up by the shotgun.

If the planes banked right then the DPA was wiped out but the shotgun survived due to its directivity. The planes literally take off every 30 seconds from Heathrow so there was no chance of any clean production audio. It was just a case of gathering the best production audio possible to facilitate ADR later on.

To me, this is a classic example of how understanding the disciplines of the art form, and, as we discussed in Chapter 4, “success or Failure: Before the Camera Even Rolls,” this clearly demonstrates the issue of planning for success, rather than what we see all too often of fixing in post what was not properly thought out and prepared for before the cameras even rolled. Thank you, Ted, for contacting me and submitting this excellent example just in time to be included in this chapter.

THE BOTTOM LINE

The bottom line is this: No matter if you are working on a multi-million-dollar blockbuster or you are cutting a wonderful little romantic comedy that was shot for a few thousand dollars on HD, the art form of what we do does not change. The strategies of how we achieve that art form within the bounds of the budget and schedule change of course, but not the art form—the art form is the same.