Data Loss Protection

Ken Perkins, Blazent Incorporated

IT professionals are tasked with the some of the most complex and daunting tasks in any organization. Some of the roles and responsibilities are paramount to the company’s livelihood and profitability and maybe even the ultimate survival of the organization. Some of the most challenging issues facing IT professionals today are securing communications and complying with the vast number of data privacy regulations. Secure communications must protect the organization against spam, viruses, and worms; securing outbound traffic; guaranteeing the availability and continuity of the core business systems (such as corporate email, Internet connectivity, and phone systems), all while facing an increasing workload with the same workforce. In addition, many organizations face challenges in meeting compliance goals, contingency plans for disasters, detecting and/or preventing data misappropriation, and dealing with hacking, both internally and externally.

Almost every week, IT professionals can open the newspaper or browse online news sites and read stories that would keep most people up at night (see sidebar, “Stealing Trade Secrets From E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company”). The dollar amounts lost are staggering and growing each year (see sidebar, “Stored Secure Information Intrusions”). Pressures of compliance regulations, brand protection, and corporate intellectual property are all driving organizations to evaluate and/or adopt data loss protection (DLP) solutions.

Stealing Trade Secrets from E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company

WILMINGTON, DE—Colm F. Connolly, United States Attorney for the District of Delaware; William D. Chase, Special Agent in Charge of the Baltimore Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Field Office; and Darryl W. Jackson, Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Export Enforcement, announced today the unsealing of a one-count Criminal Information charging Gary Min, a.k.a. Yonggang Min, with stealing trade secrets from E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (“DuPont”). Min pleaded guilty to the charge on November 13, 2006. The offense carries a maximum prison sentence of 10 years, a fine of up to $250,000, and restitution.

Pursuant to the terms of the plea agreement, Min admitted that he misappropriated DuPont’s proprietary trade secrets without the company’s consent and agreed to cooperate with the government.

According to facts recited by the government and acknowledged by Min at Min’s guilty plea hearing, Min began working for DuPont as a research chemist in November 1995. Throughout his tenure at DuPont, Min’s research focused generally on polyimides, a category of heat and chemical resistant polymers, and more specifically on high-performance films. Beginning in July 2005, Min began discussions with Victrex PLC about possible employment opportunities in Asia. Victrex manufactures PEEK,™ a polymer compound that is a functional competitor with two DuPont products, Vespel® and Kapton®. On October 18, 2005, Min signed an employment agreement with Victrex, with his employment set to begin in January 2006. Min did not tell DuPont that he had accepted a job with Victrex, however, until December 12, 2005.

Between August 2005 and December 12, 2005, Min accessed an unusually high volume of abstracts and full-text .pdf documents off of DuPont’s Electronic Data Library (“EDL”). The EDL server, which is located at DuPont’s experimental station in Wilmington, is one of DuPont’s primary databases for storing confidential and proprietary information. Min downloaded approximately 22,000 abstracts from the EDL and accessed approximately 16,706 documents—fifteen times the number of abstracts and reports accessed by the next highest user of the EDL for that period. The vast majority of Min’s EDL searches were unrelated to his research responsibilities and his work on high-performance films. Rather, Min’s EDL searches covered most of DuPont’s major technologies and product lines, as well as new and emerging technologies in the research and development stage. The fair market value of the technology accessed by Min exceeded $400 million.

After Min gave DuPont notice that he was resigning to take a position at Victrex, DuPont uncovered Min’s unusually-high EDL usage. DuPont immediately contacted the FBI in Wilmington, which launched a joint investigation with the United States Attorney’s Office and the United States Department of Commerce. Min began working at Victrex on January 1, 2006. On or about February 2, 2006, Min uploaded approximately 180 DuPont documents—including documents containing confidential, trade secret information—to his Victrex-assigned laptop computer. On February 3, 2006, DuPont officials told Victrex officials in London about Min’s EDL activities and explained that Min had accessed confidential and proprietary action. Victrex officials seized Min’s laptop computer from him on February 8, 2006, and subsequently turned it over to the FBI.”

Stored Secure Information Intrusions

Retailer TJX suffered an unauthorized intrusion or intrusions into portions of its computer system that process and store information related to credit and debit card, check and unreceipted merchandise return transactions (the intrusion or intrusions, collectively, the “Computer Intrusion”), which was discovered during the fourth quarter of fiscal 2007. The theft of customer data primarily related to portions of the transactions at its stores (other than Bob’s Stores) during the periods 2003 through June 2004 and mid-May 2006 through mid-December 2006.

During the first six months of fiscal 2007 TJX incurred pretax costs of $38 million for costs related to the Computer Intrusion. In addition, in the second quarter ended July 28, 2007, TJX established a pretax reserve for its estimated exposure to potential losses related to the Computer Intrusion and recorded a pretax charge of $178 million. As of January 26, 2008, TJX reduced the reserve by $19 million, primarily due to insurance proceeds with respect to the Computer Intrusion, which had not previously been reflected in the reserve, as well as a reduction in estimated legal and other fees as the Company has continued to resolve outstanding disputes, litigation, and investigations. This reserve reflects the Company’s current estimation of probable losses in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles with respect to the Computer Intrusion and includes a current estimation of total potential cash liabilities from pending litigation, proceedings, investigations and other claims, as well as legal and other costs and expenses, arising from the Computer Intrusion. This reduction in the reserve results in a credit to the Provision for Computer Intrusion related costs of $19 million in the fiscal 2007 fourth quarter and a pretax charge of $197 million for the fiscal year ended January 26, 2008.

The Provision for Computer Intrusion related costs increased fiscal 2008 fourth quarter net income by $11 million, or $0.02 per share, and reduced net income from continuing operations for the full fiscal 2008 year by $119 million, or $0.25 per share.

Note: In the June 2007 General Accounting Office article, “GAO-07-737 Personal Information: Data Breaches Are Frequent, But Evidence of Resulting Identity Theft Is Limited; However, the Full Extent Is Unknown,” 31 companies that responded to a 2006 survey said they incurred an average of $1.4 million per data breach.

The list of concerning stories of companies and organizations affected by data breaches grows every year. The penalties are not limited to financial losses but sometimes hurt people personally through invasion of privacy. The organizations harmed are not limited to Wall Street and have implications of influencing the national security of countries worldwide. The pressures across entire organizations are growing to keep data in its place and keep it a secure manner. It is no wonder that DLP solutions are included in most IT organizations’ initiatives for the next few years.

So, with this in mind, this chapter could be considered an introduction and a primer to the concepts of DLP. The terms, acronyms, and concepts discussed here will give the reader a baseline understanding of how to investigate and evaluate DLP applications in the market today. However, this chapter should not be considered the authoritative single source of information on the topic.

1. Precursors of DLP

Even before the Internet and all the wonderful benefits it brings to the world, organizations’ data were exposed to the outside world. Modems, telex, and fax machines were some of the first enablers of electronic communications. Electronic methods of communications, by default, increase the speed and ease of communication, but they also create inherent security risks. Once IT organizations noticed they were at risk, they immediately started focusing on creating impenetrable moats to surround the “IT castle.” As communication protocols standardized and with the mainstream adoption of the Internet, Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) became the generally accepted default language of the Internet. This phenomenon brought to light external-facing security technologies and consequently their quick adoption. Some common technologies that protect TCP/IP networks from external threats are:

• Firewalls. Inspect network traffic passing through it, and denies or permits passage based on a set of rules.

• Intrusion detection systems (IDSs). Sensors log potential suspicious activity and allow for the remediation of the issue.

• Intrusion prevention systems (IPSs). React to suspicious activity by automatically performing a reset to the connection or by adjusting the firewall to block network traffic from the suspected malicious source.

• Antivirus protection. Attempts to identify, neutralize, or eliminate malicious software.

• Antispam technology. Attempts to let in “good” emails and keep out “bad” emails.

The common thread in these technologies: Keep the “bad guys” out while letting normal, efficient business processes occur. These technologies initially offered some very high-level, nongranular features such as blocking a TCP/IP port, allowing communications to and from a certain range of IP addresses, identifying keywords (without context or much flexibility), signatures of viruses, and blocking spam that used common techniques used by spammers.

Once IT organizations had a good handle on external-facing services, the next logical thought comes to mind: What happens if the “bad guy,” undertrained or undereducated users, already have access to the information contained in an organization? In some circles of IT, this animal is simply known as an employee. Employees, by their default, “inside” nature, have permission to access the company’s most sensitive information to accomplish their jobs. Even though the behavior of nonmalicious employees might cause as much damage as an intentional act, the disgruntled employee or insider is a unique threat that needs to be addressed.

The disgruntled insider, working from within an organization, is a principal source of computer crimes. Insiders may not need a great deal of knowledge about computer hacking because their knowledge of a victim’s system often allows them to gain unrestricted access to cause damage to the system or to steal system data. With the advent of technology outsourcing, even nonemployees have the rights to view/create/delete some of the most sensitive data assets within an organization. The insider threat could also include contractor personnel and even vendors working onsite. To make matters worse, the ease of finding information to help with hacking systems is no harder than typing a search string into popular search engines. The following is an example of how easy it is for non-“black hats” to perform complicated hacks without much technical knowledge:

1. Open a browser that is connected to the Internet.

2. Go to any popular Internet search engine site.

3. Search for the string “cracking WEP How to.”

Note: Observe the number of articles, most with step-by-step instructions, on how to find the Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) encryption key to “hijack” a Wi-Fi access point.

So, what happens if an inside worker puts the organization at risk through his activity on the network or corporate assets? The next wave of technologies that IT organizations started to address dealt with the “inside man” issue. Some examples of these types of technologies include:

• Web filtering. Can allow/deny content to a user, especially when it is used to restrict material delivered over the Web.

• Proxy servers. Services the requests of its clients by forwarding requests to other servers and may block entire functionality such as Internet messaging/chat, Web email, and peer-to-peer file sharing programs.

• Audit systems (both manual and automated). Technology that records every packet of data that enters/leave the organization’s network. Can be thought of as a network “VCR.” Automated appliances feature post-event investigative reports. Manual systems might just use open-source packet-capture technologies writing to a disk for a record of network events.

• Computer forensic systems. Is a branch of forensic science pertaining to legal evidence found in computers and digital storage media. Computer forensics adheres to standards of evidence admissible in a court of law. Computer forensics experts investigate data storage devices (such as hard drives, USB drives, CD-ROMs, floppy disks, tape drives, etc.), identifying, preserving, and then analyzing sources of documentary or other digital evidence.

• Data stores for email governance.

• IM- and chat-monitoring services. The adoption of IM across corporate networks outside the control of IT organizations creates risks and liabilities for companies who do not effectively manage and support IM use. Companies implement specialized IM archiving and security products and services to mitigate these risks and provide safe, secure, productive instant-messaging capabilities to their employees.

• Document management systems. A computer system (or set of computer programs) used to track and store electronic documents and/or images of paper documents.

Each of these technologies are necessary security measures implemented in [or “by”] IT organizations to address point or niche areas of vulnerabilities in corporate networks and computer assets.

Even before DLP became a concept, IT organizations have been practicing the tenets of DLP for years. Firewalls at the edge of corporate networks can block access to IP addresses, subnets, and Internet sites. One could say this is the first attempt to keep data where it should reside, within the organization. DLP should be looked at nothing more than the natural progression of the IT security life cycle.

2. What is DLP?

Data loss protection is a term that has percolated up from the alphabet soup of computer security concepts in the past few years. Known in the past as information leak detection and prevention (ILDP), used by IDC; information protection and control (IPC); information leak prevention (ILP), coined by Forrester; content monitoring and filtering (CMF), suggested by Gartner; or extrusion prevention system (EPS), the opposite of intrusion prevention system (IPS), the acronym DLP seems to have won out. No matter what acronym of the day is used, DLP is an automated system to identify anything that leaves the organization that could harm the organization.

DLP applications try to move away from the point or niche application and give a more holistic approach to coverage, remediation and reporting of data issues. One way of evaluating an organization’s level of risk is to look around in an unbiased fashion. The most benign communication technologies could be used against the organization and cause harm.

Before embarking on a DLP project, understanding some example types of harm and/or the corresponding regulations can help with the evaluation. The following sidebar, “Current Data Privacy Legislation and Standards,” addresses only a fraction of current data privacy legislation and standards but should give the reader a good understanding of the complexities involved in protecting data.

Current Data Privacy Legislation and Standards

Examples of Harm

Scenario

An administrative assistant confirms a hotel reservation for an upcoming conference by emailing a spreadsheet with employee’s credit card numbers with expiration dates; sometimes if they want to make it really easy for the “bad guys,” an admin will include the credit card’s “secret” PIN, also known as card verification number (CVN).

Problem

Possible violation of GLBA and puts the organization’s employees at risk for identity theft and credit card fraud.

Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

GLBA compliance is mandatory; whether a financial institution discloses nonpublic information or not, there must be a policy in place to protect the information from foreseeable threats in security and data integrity.

Major components put into place to govern the collection, disclosure, and protection of consumers’ nonpublic personal information; or personally identifiable information:

• Financial Privacy Rule

• Safeguards Rule

• Pretexting Protection

Financial Privacy Rule

(Subtitle A: Disclosure of Nonpublic Personal Information, codified at 15 U.S.C.  6801–6809)

6801–6809)

The Financial Privacy Rule requires financial institutions to provide each consumer with a privacy notice at the time the consumer relationship is established and annually thereafter. The privacy notice must explain the information collected about the consumer, where that information is shared, how that information is used, and how that information is protected. The notice must also identify the consumer’s right to opt out of the information being shared with unaffiliated parties per the Fair Credit Reporting Act. Should the privacy policy change at any point in time, the consumer must be notified again for acceptance. Each time the privacy notice is reestablished, the consumer has the right to opt-out again. The unaffiliated parties receiving the nonpublic information are held to the acceptance terms of the consumer under the original relationship agreement. In summary, the financial privacy rule provides for a privacy policy agreement between the company and the consumer pertaining to the protection of the consumer’s personal nonpublic information.

Safeguards Rule

(Subtitle A: Disclosure of Nonpublic Personal Information, codified at 15 U.S.C.  6801–6809)

6801–6809)

The Safeguards Rule requires financial institutions to develop a written information security plan that describes how the company is prepared for and plans to continue to protect clients’ nonpublic personal information. (The Safeguards Rule also applies to information of those no longer consumers of the financial institution.) This plan must include:

• Denoting at least one employee to manage the safeguards

• Constructing a thorough risk management on each department handling the nonpublic information

• Developing, monitoring, and testing a program to secure the information

• Changing the safeguards as needed with the changes in how information is collected, stored, and used

This rule is intended to do what most businesses should already be doing: protect their clients. The Safeguards Rule forces financial institutions to take a closer look at how they manage private data and to do a risk analysis on their current processes. No process is perfect, so this has meant that every financial institution has had to make some effort to comply with the GLBA.

Pretexting Protection

(Subtitle B: Fraudulent Access to Financial Information, codified at 15 U.S.C.  6821–6827)

6821–6827)

Pretexting (sometimes referred to as social engineering) occurs when someone tries to gain access to personal nonpublic information without proper authority to do so. This may entail requesting private information while impersonating the account holder, by phone, by mail, by email, or even by phishing (i.e., using a phony Web site or email to collect data). The GLBA encourages the organizations covered by the GLBA to implement safeguards against pretexting. For example, a well-written plan to meet GLBA’s Safeguards Rule (“develop, monitor, and test a program to secure the information”) ought to include a section on training employees to recognize and deflect inquiries made under pretext. In the United States, pretexting by individuals is punishable as a common law crime of False Pretenses.

Scenario

An HR employee, whose main job function is to process claims, forwards via email an employee’s Explanation of Benefits that contains a variety of Protected Health Information. The email is sent in the clear, unencrypted, to the organization’s healthcare provider.

Problem

Could violate the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), depending on the type of organization.

The Privacy Rule

The Privacy Rule took effect on April 14, 2003, with a one-year extension for certain “small plans.” It establishes regulations for the use and disclosure of Protected Health Information (PHI). PHI is any information about health status, provision of health care, or payment for health care that can be linked to an individual. This is interpreted rather broadly and includes any part of a patient’s medical record or payment history.

Covered entities must disclose PHI to the individual within 30 days upon request. They also must disclose PHI when required to do so by law, such as reporting suspected child abuse to state child welfare agencies.

A covered entity may disclose PHI to facilitate treatment, payment, or healthcare operations or if the covered entity has obtained authorization from the individual. However, when a covered entity discloses any PHI, it must make a reasonable effort to disclose only the minimum necessary information required to achieve its purpose.

The Privacy Rule gives individuals the right to request that a covered entity correct any inaccurate PHI. It also requires covered entities to take reasonable steps to ensure the confidentiality of communications with individuals. For example, an individual can ask to be called at his or her work number, instead of home or cell phone number.

The Privacy Rule requires covered entities to notify individuals of uses of their PHI. Covered entities must also keep track of disclosures of PHI and document privacy policies and procedures. They must appoint a Privacy Official and a contact person responsible for receiving complaints and train all members of their workforce in procedures regarding PHI.

An individual who believes that the Privacy Rule is not being upheld can file a complaint with the Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights (OCR).

Scenario

An employee opens an email whose subject is “25 Reasons Why Beer is Better than Women.” The employee finds this joke amusing and forwards the email to other coworkers using the corporate email system.

Problem

Puts the organization in an exposed position for claims of sexual harassment and a hostile workplace environment.

Legislation

In the U.S., the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Title VII prohibits employment discrimination based on race, sex, color, national origin, or religion. The prohibition of sex discrimination covers both females and males. This discrimination occurs when the sex of the worker is made a condition of employment (i.e., all female waitpersons or male carpenters) or where this is a job requirement that does not mention sex but ends up barring many more persons of one sex than the other from the job (such as height and weight limits).

In 1998, Chevron settled, out of court, a lawsuit brought by several female employees after the “25 Reasons” email was widely circulated throughout the organization. Ultimately, Chevron settled out of court for $2.2 million.

Scenario

A retail store server electronically transmits daily point-of-sale (POS) transactions to the main corporate billing server. The POS system records the time, date, register number, employee number, part number, quantity, and if paid for by credit card, the card number. This transaction occurs nightly as part of a batch job and is transmitted over the store’s Wi-Fi network.

Problem

PCI DSS stands for Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard. It was developed by the major credit card companies as a guideline to help organizations that process card payments prevent credit-card fraud, cracking, and various other security vulnerabilities and threats. A company processing, storing, or transmitting payment card data must be PCI DSS compliant or risk losing its ability to process credit card payments and being audited and/or fined. Merchants and payment card service providers must validate their compliance periodically. This validation gets conducted by auditors (that is persons who are the PCI DSS Qualified Security Assessors, or QSAs). Although individuals receive QSA status, reports on compliance can only be signed off by an individual QSA on behalf of a PCI council-approved consultancy. Smaller companies, processing fewer than about 80,000 transactions a year, are allowed to perform a self-assessment questionnaire. Penalties are often accessed and fines of $25,000 per month are possible for large merchants for noncompliance.

PCI DSS requires 12 requirements to be in compliance:

Requirement 1: Install and maintain a firewall configuration to protect cardholder data

Firewalls are computer devices that control computer traffic allowed into and out of a company’s network, as well as traffic into more sensitive areas within a company’s internal network. A firewall examines all network traffic and blocks those transmissions that do not meet the specified security criteria.

Requirement 2: Do not use vendor-supplied defaults for system passwords and other security parameters

Hackers (external and internal to a company) often use vendor default passwords and other vendor default settings to compromise systems. These passwords and settings are well known in hacker communities and easily determined via public information.

Requirement 3: Protect stored cardholder data

Encryption is a critical component of cardholder data protection. If an intruder circumvents other network security controls and gains access to encrypted data, without the proper cryptographic keys, the data is unreadable and unusable to that person. Other effective methods of protecting stored data should be considered as potential risk mitigation opportunities. For example, methods for minimizing risk include not storing cardholder data unless absolutely necessary, truncating cardholder data if full PAN is not needed and not sending PAN in unencrypted emails.

Requirement 4: Encrypt transmission of cardholder data across open, public networks

Sensitive information must be encrypted during transmission over networks that are easy and common for a hacker to intercept, modify, and divert data while in transit.

Requirement 5: Use and regularly update anti-virus software or programs

Many vulnerabilities and malicious viruses enter the network via employees’ email activities. Antivirus software must be used on all systems commonly affected by viruses to protect systems from malicious software.

Requirement 6: Develop and maintain secure systems and applications

Unscrupulous individuals use security vulnerabilities to gain privileged access to systems. Many of these vulnerabilities are fixed by vendor-provided security patches. All systems must have the most recently released, appropriate software patches to protect against exploitation by employees, external hackers, and viruses. Note: Appropriate software patches are those patches that have been evaluated and tested sufficiently to determine that the patches do not conflict with existing security configurations. For in-house developed applications, numerous vulnerabilities can be avoided by using standard system development processes and secure coding techniques.

Requirement 7: Restrict access to cardholder data by business need-to-know

This requirement ensures critical data can only be accessed by authorized personnel.

Requirement 8: Assign a unique ID to each person with computer access

Assigning a unique identification (ID) to each person with access ensures that actions taken on critical data and systems are performed by, and can be traced to, known and authorized users.

Requirement 9: Restrict physical access to cardholder data

Any physical access to data or systems that house cardholder data provides the opportunity for individuals to access devices or data and to remove systems or hardcopies, and should be appropriately restricted.

Requirement 10: Track and monitor all access to network resources and cardholder data

Logging mechanisms and the ability to track user activities are critical. The presence of logs in all environments allows thorough tracking and analysis if something does go wrong. Determining the cause of a compromise is very difficult without system activity logs.

Requirement 11: Regularly test security systems and processes

Vulnerabilities are being discovered continually by hackers and researchers, and being introduced by new software. Systems, processes, and custom software should be tested frequently to ensure security is maintained over time and with any changes in software.

Requirement 12: Maintain a policy that addresses information security for employees and contractors

A strong security policy sets the security tone for the whole company and informs employees what is expected of them. All employees should be aware of the sensitivity of data and their responsibilities for protecting it.

Organizations are facing pressures to become Sarbanes-Oxley compliant.

SOX Section 404: Assessment of internal control

The most contentious aspect of SOX is Section 404, which requires management and the external auditor to report on the adequacy of the company’s internal control over financial reporting (ICFR). This is the most costly aspect of the legislation for companies to implement, as documenting and testing important financial manual and automated controls requires enormous effort.

Under Section 404 of the Act, management is required to produce an “internal control report” as part of each annual Exchange Act report. The report must affirm “the responsibility of management for establishing and maintaining an adequate internal control structure and procedures for financial reporting.” The report must also “contain an assessment, as of the end of the most recent fiscal year of the Company, of the effectiveness of the internal control structure and procedures of the issuer for financial reporting.” To do this, managers are generally adopting an internal control framework such as that described in Committee of Sponsoring Organization of the Treadway Commission (COSO).

Both management and the external auditor are responsible for performing their assessment in the context of a top-down risk assessment, which requires management to base both the scope of its assessment and evidence gathered on risk. Both the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) and SEC recently issued guidance on this topic to help alleviate the significant costs of compliance and better focus the assessment on the most critical risk areas.

The recently released Auditing Standard No. 5 of the PCAOB, which superseded Auditing Standard No 2. has the following key requirements for the external auditor:

• Assess both the design and operating effectiveness of selected internal controls related to significant accounts and relevant assertions, in the context of material misstatement risks

• Understand the flow of transactions, including IT aspects, sufficiently to identify points at which a misstatement could arise

• Evaluate company-level (entity-level) controls, which correspond to the components of the COSO framework

• Perform a fraud risk assessment

• Evaluate controls designed to prevent or detect fraud, including management override of controls

• Evaluate controls over the period-end financial reporting process;

• Scale the assessment based on the size and complexity of the company

• Rely on management’s work based on factors such as competency, objectivity, and risk

• Evaluate controls over the safeguarding of assets

• Conclude on the adequacy of internal control over financial reporting

The recently released SEC guidance is generally consistent with the PCAOB’s guidance above, only intended for management.

After the release of this guidance, the SEC required smaller public companies to comply with SOX Section 404, companies with year ends after December 15, 2007. Smaller public companies performing their first management assessment under Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 may find their first year of compliance after December 15, 2007 particularly challenging. To help unravel the maze of uncertainty, Lord & Benoit, a SOX compliance company, issued “10 Threats to Compliance for Smaller Companies” (www.section404.org/pdf/sox_404_10_threats_to_compliance_for_smaller_public_companies.pdf), which gathered historical evidence of material weaknesses from companies with revenues under $100 million. The research was compiled aggregating the results of 148 first-time companies with material weaknesses and revenues under $100 million. The following were the 10 leading material weaknesses in Lord & Benoit’s study: accounting and disclosure controls, treasury, competency and training of accounting personnel, control environment, design of controls/lack of effective compensating controls, revenue recognition, financial closing process, inadequate account reconciliations, information technology and consolidations, mergers, intercompany accounts.

Scenario

A guidance counselor at a high school gets a request from a student’s prospective college. The college asked for the student’s transcripts. The guidance counselor sends the transcript over the schools email system unencrypted.

Problem

FERPA privacy concerns, depending on the age of the student.

Legislation

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) (20 U.S.C.  1232g; 34 CFR Part 99) is a federal law that protects the privacy of student education records. The law applies to all schools that receive funds under an applicable program of the U.S. Department of Education.

1232g; 34 CFR Part 99) is a federal law that protects the privacy of student education records. The law applies to all schools that receive funds under an applicable program of the U.S. Department of Education.

FERPA gives parents certain rights with respect to their children’s education records. These rights transfer to the student when he or she reaches the age of 18 or attends a school beyond the high school level. Students to whom the rights have transferred are “eligible students.”

Parents or eligible students have the right to inspect and review the student’s education records maintained by the school. Schools are not required to provide copies of records unless, for reasons such as great distance, it is impossible for parents or eligible students to review the records. Schools may charge a fee for copies.

Parents or eligible students have the right to request that a school correct records that they believe to be inaccurate or misleading. If the school decides not to amend the record, the parent or eligible student then has the right to a formal hearing. After the hearing, if the school still decides not to amend the record, the parent or eligible student has the right to place a statement with the record setting forth his or her view about the contested information.

Generally, schools must have written permission from the parent or eligible student in order to release any information from a student’s education record. However, FERPA allows schools to disclose those records, without consent, to the following parties or under the following conditions (34 CFR  99.31):

99.31):

• School officials with legitimate educational interest

• Other schools to which a student is transferring

• Specified officials for audit or evaluation purposes

• Appropriate parties in connection with financial aid to a student

• Organizations conducting certain studies for or on behalf of the school

• Accrediting organizations

• To comply with a judicial order or lawfully issued subpoena

• Appropriate officials in cases of health and safety emergencies

• State and local authorities, within a juvenile justice system, pursuant to specific State law

Schools may disclose, without consent, “directory” information such as a student’s name, address, telephone number, date and place of birth, honors and awards, and dates of attendance. However, schools must tell parents and eligible students about directory information and allow parents and eligible students a reasonable amount of time to request that the school not disclose directory information about them. Schools must notify parents and eligible students annually of their rights under FERPA. The actual means of notification (special letter, inclusion in a PTA bulletin, student handbook, or newspaper article) is left to the discretion of each school.

Scenario

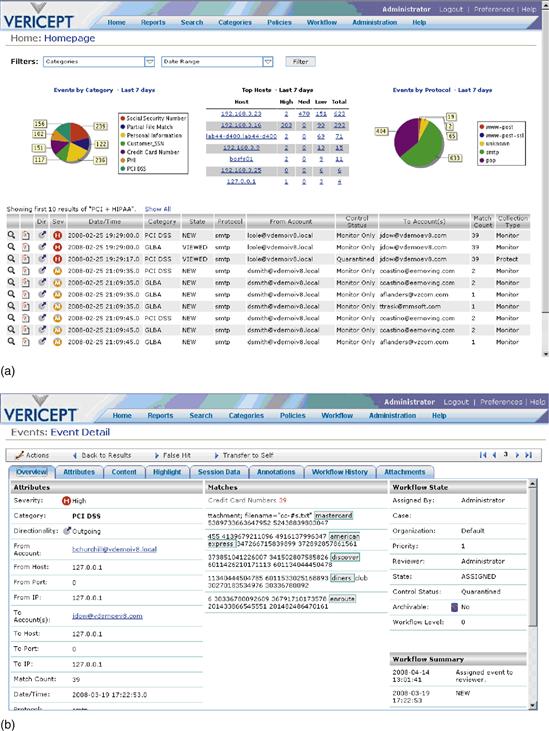

Employee job hunting, posting resumes and trying to find another job while working. See Figure 43.1 for an example of a DLP system capturing the full content of a user going through the resignation process.

Figure 43.1 Webmail event: Content rendering of a resignation event.

Problem

Loss of productivity for that employee.

Warning sign for a possible disgruntled employee.

3. Where to Begin?

A reasonable place to begin talking about DLP is with the department of the organization that handles corporate policy and/or governance (see sidebar, “An Example of an Acceptable Use Policy”). Monitoring employees is at best an interesting proposition. Corporate culture can drive whether monitoring of any kind is even allowed. A good litmus test would be the types of notice that appear in the employee handbook.

An Example of an Acceptable Use Policy

Use of Email and Computer Systems

All information created, accessed or stored using company applications, systems, or resources, including email, is the property of the company. Users do not have a right to privacy regarding any activity conducted using the company’s system. The company can review, read, access, or otherwise monitor email and all activities on the company system or any other system accessed by use of the company system. In addition, the Company could be required to allow others to read email or other documents on the company’s system in the context of a lawsuit or other legal action.

All users must abide by the rules of network etiquette, which include being polite and using the network and the Internet in a safe and legal manner. The company or authorized company officials will make a good faith judgment as to which materials, files, information, software, communications, and other content and activity are permitted and prohibited based on the following guidelines and under the particular circumstances.

Among the uses that are considered unacceptable and constitute a violation of this policy are the following:

• Using, transmitting, receiving, or seeking inappropriate, offensive, swearing, vulgar, profane, suggestive, obscene, abusive, harassing, belligerent, threatening, defamatory (harming another’s reputation by lies), or misleading language or materials; revealing personal information such as another’s home address, home telephone number, or Social Security number; making ethnic, sexual-preference, age or gender-related slurs or jokes.

• Users may never harass, intimidate, threaten others, or engage in other illegal activity (including pornography, terrorism, espionage, theft, or drugs) by email or other posting. All such instances should be reported to management for appropriate action. In addition to violating this policy, such behavior may also violate other company policies or civil or criminal laws.

• Among the uses that are considered unacceptable and constitute a violation of this policy are downloading or transmitting copyrighted materials without permission from the owner of the copyright on those materials. Even if materials on the network or the Internet are not marked with the copyright symbol, you should assume that they are protected under copyright laws unless there is explicit permission from the copyright holder on the materials to use them.

• Users must not use email or other communications methods, including but not limited to news group posting, blogs, forums, instant messaging, and chat servers, to send company proprietary or confidential information to any unauthorized party. Such information may be disclosed to authorized persons in encrypted files if sent over publicly accessible media such as the Internet or other broadcast media such as wireless communication. Such information may be sent in unencrypted files only within the company system. Users are responsible for properly labeling such information.

Certain specific policies extend the Company’s acceptable use policy by placing further restrictions on that activity. Examples include, but are not limited to: software usage, network usage, shell policy, remote access policy, wireless policy, and the mobile email access policy. These and any additional policies are available from the IT Web site on the intranet.

Your use of the network and the Internet is a privilege, not a right. If you violate this policy, at a minimum you will be subject to having your access to the network and the Internet terminated. You breach this policy not only by affirmatively violating the above provisions but also by failing to report any violations of this policy by other users which come to your attention. Further, you violate this policy if you permit another to use your account or password to access the network or the Internet, including but not limited to someone whose access has been denied or terminated. Sharing your account with anyone is a violation of this policy. It is your responsibility to keep your account secure by choosing a sufficiently complex password and changing it on a regular basis.

Another good indicator that the organization would be a good fit for a DLP application is the sign-on screen that appears before or after a computer user logs on to her workstation (see sidebar, “Accessing a Company’s Information System”).

Accessing a Company’s Information System

You are accessing a Company’s information system (IS) that is provided for Company-authorized use only. By using this IS, you consent to the following conditions:

• The Company routinely monitors communications occurring on this IS, and any device attached to this IS, for purposes including, but not limited to, penetration testing, monitoring, network defense, quality control, and employee misconduct, law enforcement, and counterintelligence investigations.

• At any time the Company may inspect and/or seize data stored on this IS and any device attached to this IS.

• Communications occurring on or data stored on this IS, or any device attached to this IS, are not private. They are subject to routine monitoring and search.

• Any communications occurring on or data stored on this IS, or any device attached to this IS, may be disclosed or used for any Company-authorized purpose.

• Security protections may be utilized on this IS to protect certain interests that are important to the Company. For example, password, access cards, encryption or biometric access controls provide security for the benefit of the Company. These protections are not provided for your benefit or privacy and may be modified or eliminated at the Company’s discretion.

Some organizations are more apt to take advantage of the laws and rights that companies have to defend themselves. Simply asking around and performing informal interviews with Human Resources, Security, and Legal can save days and weeks of time down the line.

In summary, implementing a DLP application without the proper Human Resources, Security, and Legal policies could be a waste of time because IT professionals will catch employees violating security standard. The events in a DLP system must be actionable and have “teeth” for changes to take place.

4. Data is Like Water

As most anyone who has had a water leak in dwelling knows, water will find a way out of where it is supposed to go. Pipes are meant to direct the proper flow of water both in and out. If a leak happens, the occupant will eventually find a damp spot, a watermark, or a real drip. It might take minutes or days to notice the leak and might take just as long to find the source of the leak.

Much like the water analogy, employees are given data “pipes” to do their jobs with enabling technology provided by the IT organization. Instead of water flowing through, data can ingress/egress the organization in multiple methods.

Corporate email is a powerful efficient time saving tool that speeds communication. A user can attach a 10 megabyte file, personal pictures, a recipe for chili and next quarter’s marketing plan or an acquisition target. Chat and IM is the quickest growing form of electronic communication and a great enabler of efficient workflow. Files can be sent as well over these protocols or “pipes.” Web mail is usually the “weapon of choice” by users who like to conduct personal business at work. Web mail allows users to attach files of any type.

Thus, the IT network “plumbing” needs to be monitored, maintained, and evaluated on an ongoing basis. The U.S. government has published a complete and well-rounded standard that organizations can use as a good first step to compare where they are strong and where they can use improvement.

The U.S. Government Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA) offers reasonable guidelines that most organizations could benefit by adopting. Even though FISMA is mandated for government agencies and contractors, it can be applied to the corporate world as well.

FISMA sets forth a comprehensive framework for ensuring the effectiveness of security controls over information resources that support federal operations and assets. FISMA’s framework creates a cycle of risk management activities necessary for an effective security program, and these activities are similar to the principles noted in our study of the risk management activities of leading private sector organizations—assessing risk, establishing a central management focal point, implementing appropriate policies and procedures, promoting awareness, and monitoring and evaluating policy and control effectiveness. More specifically, FISMA requires the head of each agency to provide information security protections commensurate with the risk and magnitude of harm resulting from the unauthorized access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction of information and information systems used or operated by the agency or on behalf of the agency. In this regard, FISMA requires that agencies implement information security programs that, among other things, include:

• Periodic assessments of the risk

• Risk-based policies and procedures

• Subordinate plans for providing adequate information security for networks, facilities, and systems or groups of information systems, as appropriate

• Security awareness training for agency personnel, including contractors and other users of information systems that support the operations and assets of the agency

• Periodic testing and evaluation of the effectiveness of information security policies, procedures, and practices, performed with a frequency depending on risk, but no less than annually

• A process for planning, implementing, evaluating, and documenting remedial action to address any deficiencies

• Procedures for detecting, reporting, and responding to security incidents

• Plans and procedures to ensure continuity of operations

In addition, agencies must develop and maintain an inventory of major information systems that is updated at least annually and report annually to the Director of OMB and several Congressional Committees on the adequacy and effectiveness of their information security policies, procedures, and practices and compliance with the requirements of the act. An internal risk assessment of what types of “communication,” both manual and electronic, that are allowed within the organization can give the DLP evaluator a baseline of the type of transmission that are probably taking place.

Some types of communications that should be evaluated are not always obvious but could be just as damaging as electronic methods. The following list encompasses some of those obvious and not so obvious methods:

• Pencil and paper

• Photocopier

• Fax

• Voicemail

• Digital camera

• Jump drive

• MP3/iPod

• DVD/CD-ROM/3 in. floppy

in. floppy

• Magnetic tape

• SATA drives

• IM/chat

• FTP/FTPS

• SMTP/POP3/IMAP

• HTTP post/response

• HTTPS

• Telnet

• SCP

• P2P

• Rogue ports

• GoToMyPC

• Web conferencing systems

5. You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know

Embarking on a DLP evaluation or implementation can be a straightforward exercise. The IT professional usually has a mandate in mind and a few problems that the DLP application will address. Invariably, many other issues will arise as DLP applications do a very good job at finding most potential security and privacy issues.

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are ‘known knowns’; there are things we know we know. We also know there are ‘known unknowns’; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also ‘unknown unknowns’—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

—Donald Rumsfeld, U.S. Department of Defense, February 12, 2002

Once the corporate culture has established that DLP is worth investigating or worth implementing, the next logical step would be performing a risk/exposure assessment. Several DLP vendors offer free pilots or proof of concepts and should be leveraged to jumpstart the data risk assessment for a very low monetary cost.

A risk/exposure assessment usually involves placing a server on the edge of the corporate network and sampling/recording the network traffic that is egressing the organization. In addition, the assessment might involve look for high-risk files at rest and the activity of what is happening on the workstation environment. Most if not all DLP applications have predefined risk categories that cover a wide range of risk profiles. Some examples are:

• Regulations: GLBA, HIPAA, PCI-DSS, SOX, FERPA, PHI

• Acceptable use: Violence, gangs, profanity, adult themes, weapons, harassment, racism, pornography

• Productivity: Streaming media, resignation, shopping, Webmail

• Insider hacker activity: Root activity, nmap, stack, smashing code, keyloggers

Deciding what risk categories are most important to your organization can streamline the DLP evaluation. If data categories are turned on but not likely to impact what is truly important to the organization, the test/pilot result will contain a lot of “noise.” Focus on the “low-hanging fruit.” For example, if the organization’s life blood is customer data, focus on the categories that address those types of leaks.

Precision versus Recall

Before the precision versus recall discussion can take place, definitions are necessary:

• False positive. A false positive occurs when the DLP application-monitoring or DLP application-blocking techniques wrongly classify a legitimate transmission or event as “uninteresting” and, as a result, the event must be remediated anyway. Remediating an event is a time-consuming process which could involve one to many administrators dispositioning the event. A high number of false positives is normal during an initial implementation, but the number should fall after the DLP application is tuned.

• False negative. A false negative occurs when a transmission is not detected as interesting. The problem with false negatives is usually the DLP administrator does not know these transmissions are happening in the first place. An analogy would be a bank employee who embezzles thousands of dollars and the bank does not notice the theft until it is too late.

• True positive. Condition present and the DLP application records the event for remediation.

• True negative. Condition not present and the DLP application does not record it.

DLP application testing and tuning can involve a trade-off:

• The acceptable level of false positives (in which a nonmatch is declared to be a match).

• The acceptable level of false negatives (in which an actual match is not detected).

An evaluator can think of this process as a slider bar concept, with false negatives on the left side and false positives on the right. A properly tuned DLP application minimizes false positives and diminishes the chances of false negatives.

This iterative process of tuning is called thresholding. Creating the proper threshold eventually leads to the minimization of acceptable amounts of false positives with no or minimal false negatives.

An easy way to achieve thresholding is to make the test more restrictive or more sensitive. The more restrictive the test is, the higher the risk of rejecting true positives; and, the less sensitive the test is, the higher the risk of accepting false positives.

6. How Do DLP Applications Work?

The way that most DLP applications capture interesting events is through different kinds of analysis engines. Most support simple keyword matching. For example, any time you see the phrase “project phoenix” in a data transmission, the network event is stored for later review. Keywords can be grouped and joined. Regular expression (RegEx) support is featured in most of today’s DLP applications. Regular expressions provide a concise and flexible means for identifying strings of text of interest, such as particular characters, words, or patterns of characters. Regular expressions are written in a formal language that can be interpreted by a regular expression processor, a program that either serves as a parser generator or examines text and identifies parts that match the provided specification. A real-world example would be the expression:

Any transmission that contained the word red, bed, or even ed would be captured for later investigation. Regular expressions can also do pattern matching on credit card number and U.S. Social Security numbers:

which can be read: Any three numbers followed by an optional dash followed by any two numbers followed by an optional dash and then followed by any four numbers. Regular expressions offer a certain level of efficiencies but cannot address all DLP concerns. Weighting of either keyword(s) and/or RegEx’s can help. A real-world example might be the word red is worth three points and the SSN is worth five points, but for an event to hit the transmission, it must contain 22 points. In this example, four SSNs and the word red would trigger an event (4 times 5 plus 3 equals 23, which would trigger the event score rule). Scoring can help address the thresholding issue. To address some of the limitation of simple keyword and RegEx’s, DLP applications can also look for data “signatures” or hashes of data. Hashing creates a mathematical representation of the sensitive data and looks for that signature. Sensitive data or representative types of data can be bulk loaded from databases and example files.

7. Eat Your Vegetables

DLP is like the layers of an onion. Once the first layer of protection is implemented, the next layer should/could be addressed. There are many different forms of DLP applications, depending on the velocity and location of the sensitive data.

Data in Motion

Data in motion is an easy place to start implementing a DLP application because most can function in “passive” mode, meaning it looks at only a copy of the actual data egressing/ingressing the network. One way to look at data-in-motion monitoring is like a very intelligent VCR. Instead of recording every packet of information that passes in and out of an organization, DLP applications only capture, flag, and record the transmissions that fall within the categories/policies that are turned on (see sidebar, “Case Study: DLP Applications”). There are two main types of data-in-motion analysis:

• Passive monitoring. Using a Switched Port Analyzer (SPAN) on a router, port mirror on a switch or a network tap(s) that feeds the outbound network traffic to the DLP application for analysis.

• Active (inline) enforcement. Using an active egress port or through a proxy server, some DLP applications can stop the transmission from happening. The port itself can be reset or the proxy server can show a failure of transmission. The event that keyed off the reset or failure is still recorded.

Case Study: DLP Applications

Background

A Fortune 500 Company has tens of thousands of employees with access to the Internet through an authenticated method. The Company has recently retired a version of laptops with the associated docking station, monitors and mice. New laptops were purchased and given to the employees. The old assets were retired to a storage closet. One manager noticed some docking stations had gone missing. That in and of itself was not concerning as this company had a liberal policy of donating old computer assets to charity. After looking in the company’s Asset Management System and talking to the organization’s charity manager, the manager found this was not the case. An investigation was launched both electronically and through traditional investigative means.

Action

The organization had a DLP application in use with data-in-motion implemented. This particular DLP application had a strong acceptable use set of categories/policies. One of them was “Shopping,” which covered both traditional shopping outlets but also popular online auction sites. The DLP investigator selected the report that returns all transmissions that violated the “Shopping” category and contained the keyword of the model number of the docking station. Within seconds, a user from within their network was found auctioning the exact same model docking stations as the ones the company had just retired.

Result

The Fortune 500 Company was able to remediate a situation quickly that not only stopped the loss of physical assets, but get rid of an employee that was stealing while at work. The real value of this exercise could have been, if an employee is “ok” with stealing assets to make a few extra dollars on the company’s dime, one might ask, What else might an employee that thinks it is ok to steal do?

Data at Rest

Static computer files on drives, removable media or even tape can grow to the millions in large multinational organizations. Unless tight controls are implemented, data can spawn out of control. Even though email transmissions account for more than 80% of DLP violations, data-at-rest files that are resting where they are not supposed to be can be a major concern (see sidebar, “Case Study: Data-at-Rest Files”).

Case Study: Data-at-Rest Files

Background

A Fortune 500 Company has multiple customer service centers located throughout the United States. Each customer server representative has a personal computer with a hard drive and Internet access. The representative’s job entails taking inbound phone calls to help their customers with account management including auto-pay features. Auto-pay setup information could include taking a credit-card number and expiration date and/or setting up an electronic fund transfer payment which includes an ABA routing number and account number. This sensitive information is supposed to be entered directly into the corporate enterprise resource planning (ERP) system application. Invariably customer service representatives run into issues during this process (connectivity to the ERP system is interrupted, power goes down, computer needs to be rebooted, etc.) and sensitive data finds its way into unapproved places on the personal computer—a note text file, a word-processing document, an electronic spreadsheet, or in an email system. Even though employees went through training for their job that included handling of sensitive data, the management suspected that data was finding a way out of the ERP system. Another issue that the management faced with a very high turnover ratio and that employee training was falling behind.

Action

A DLP data-at-rest pilot was performed and over one thousand files that contained credit-card numbers and other customer personal identifiable information were found.

Result

The Fortune 500 Company was able to cleanse the hard drives of files that contained sensitive data by using the legend the DLP application provided. More important, the systemic cause of the problem had to be readdressed with training and tightening down the security of the representative, personal computers.

Data-at-rest risk can occur in other places besides the personal computer’s file system. One of the benefits of networked computer systems is the ability to share files. File shares can also pose a risk because the original owner of the file now has no idea what happened to the file after they share it.

The same can be said of many Web-based collaboration and document management platforms that are available in the market today. Collaboration tools can be used to host Web sites that can be used to access shared workspaces and documents, as well as specialized applications such as wikis, blogs, and many other forms of applications, from within a browser. Once again, the wonderful world of shared computing can also put an organization’s data at risk.

DLP application can help with databases as well and half the battle is knowing where the organizations most sensitive data resides. The data-at-rest function of DLP applications can definitely help.

Data in Use

DLP applications can also help keep data where it is supposed to stay (see sidebar, “Case Study: Data-in-Use Files”). Agent-based technologies that run resident on the guest operating system can track, monitor, block, report, quarantine or notify the usage of particular kinds of data files and/or the contents of the file itself. Policies can be centrally administered and “pushed” out of the organization’s computer assets. Since the agent is resident on the computer, it can also create an inventory of every file on the hard drives, removable media and even music players. Since the agent knows of the file systems down to the operating system level, it can allow or disallow certain types of removable media. For example, an organization might allow a USB storage device if and only if the device supports encryption. The agent will disallow any other types of USB devices such as music players, cameras, removable hard drives, and so on.

Case Study: Data-in-Use Files

Background

An electronics manufacturer has created a revolutionary new design for a cell phone and wants to keep the design and photographs of the prototype under wraps. They have had problems in the past with pictures ending up on blog sites, competitors “borrowing” design ideas, and even other countries creating similar products and launching an imitator within weeks of the initial product launch.

Action

Each document, whether a spreadsheet, document, diagram, or photograph, was secretly watermarked with a special secret code. At the same time, the main security group created an organizational unit within their main LDAP application. This was the only group that had permission to access the watermarked files. At the same time, a DLP application agent was rolled out to the computer assets within the organization. If anyone “found” a marked file and tried to do something with it, unless they were in the privileged group, access was denied and an alert (see Figure 43.2c) went back to the main DLP reporting server.

Figure 43.2 (a) Email with user notification on the fly; (b) PC user tries to access a protected document; and (c) policy prompts a justification alert.

Result

The electronics manufacturer was able to deliver its revolutionary product to market in a secure manner and on time.

Much like the different flavors of DLP that are available (data in motion, data at rest and data in use), conditions of the severity of action that DLP applications take on the event can vary. A good place to diagnose the problems organizations are currently facing would be to start with Monitoring (see sidebar, “Case Study in Monitoring”). Monitoring is only capturing the actual event that took place to review at a later time. Most DLP applications offer real-time or near real-time monitoring of events that violated a policy. Monitoring coupled with escalation can help most organizations immediately. Escalation works well with monitoring as when an event happens, rules can be put into place on who should be notified and/or how the notification should take place. Email is the most common form of escalation.

Case Study in Monitoring

Background

A large data provider of financial account records dealt with millions of customer records. The customer records contained account numbers and other nonpublic, personal information (NPPI) and Social Security numbers. The data provider mandated the protection of this type of sensitive data was the top priority of the upcoming year.

Action

A DLP application was implemented. Social Security number, customer information, and NPPI categories were turned on. After one week, over 1000 data transmissions were captured over various protocols (email, FTP, and Web traffic). After investigating the results, over 800 transmissions were found to have come from a pair of servers that was set up to transmit account information to partners.

Result

By simply changing the type of transmission to a secure, encrypted format, the data was secured with no interruption of normal business processes. Monitoring was the way to go in this case and made the organization more secure and minimized the number of processes that were impacted.

Another action that DLP application supports is notification. Notification can temporarily interrupt that transmission of an event and could require user interaction. See Figure 43.2a for an example of the kind of “bounce” email a user could receive if she sends an email containing sensitive information. See Figure 43.2b for an example of the type of notification a user could see if he tries to open a sensitive data document. The DLP application could make the user justify why access is needed, deny access, or simply log the attempt back to the main reporting console.

Notification can enhance the current user education program in place and serve as a gentle reminder. The onus of action lies solely on the end user and does not take resources from the already thinly stretched IT organization.

The next level of severity of implementing DLP could be quarantining and then outright blocking. Quarantining events places the transmission in “stasis” for review from a DLP administrator. The quarantine administrator can release, release with encryption, block, or send the event back to the offending user for remediation. Blocking is an action that stops the transmission in its entirety based upon the contents.

Both quarantining and blocking should be used sparingly and only after the organization feels comfortable with the policies and procedures. The first time an executive tries to send a transmission and cannot because of the action set forth in the DLP application, the IT professional can potentially lose his job.

8. It’s a Family Affair, Not Just It Security’s Problem

The IT organization does and most likely maintains the corporate email system; almost everyone across all departments within an organization uses email. The same can be said for the DLP application. Even though IT will implement and maintain the DLP application, the events will most likely come from all different types of users across the entire organization. When concerning events are captured and there will be many captured by the DLP application, most management will turn to IT to resolve the problem. The IT organization should not become the “police and judge.” Each business unit should have published standards on how events should be handled and escalated.

Most DLP applications can segregate duties to allow non-IT personnel to review the disposition of the event captured. One way to address DLP would be to assign certain types of events to administrators in the appropriate department. If a racial email is captured, the most appropriate department might be a Human Resource employee. If a personal information transmission is captured, a compliance officer should be assigned. IT might be tasked if the nature of the event is hacking related.

Users can also have a level of privilege within the DLP application. Reviewers can be assigned to initial investigations of only certain types or all events. If necessary, an event can be escalated to a reviewer’s superior. Users can have administrative or reports-only rights.

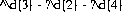

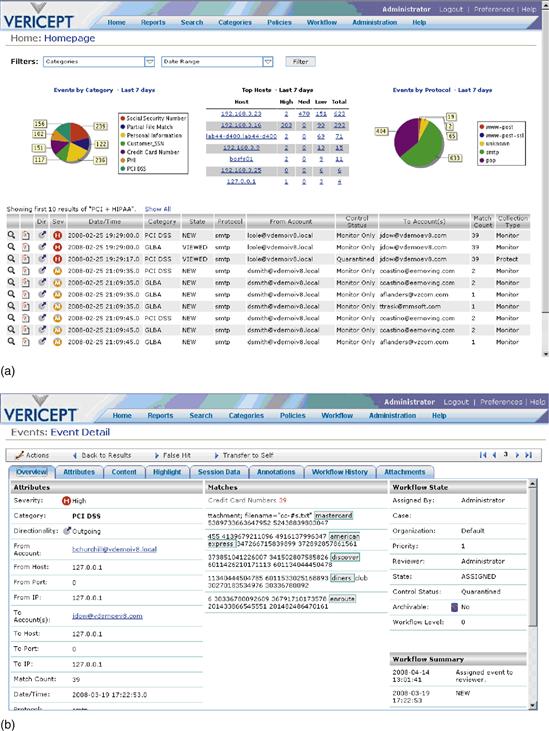

Each of these functions relates to the concept of workflow within the DLP application. Events need to be prioritized, escalated, reviewed, annotated, ignored and eventually closed. The workflow should be easy to use across the DLP community and reports should be easily assessable and created/tuned. See Figure 43.3a for an example of an Executive Dashboard that allows the user to quickly assess the state of risk and allows for a quick-click drill down for more granular information. Figure 43.3b is the result of a click from the Executive Dashboard to the full content capture of the event.

Figure 43.3 (a) Dashboard; (b) Email Event Overview.

9. Vendors, Vendors Everywhere! Who Do You Believe?

At the end of the day the DLP market and applications are maturing at an incredible pace. Vendors are releasing new features and functions almost every calendar quarter. In the past, when monitoring seem sufficient to diagnose the central issue of data security, the marketplace was demanding more control, more granularity, easier user interfaces, and more actionable reports, as well as moving the DLP application off the main network egress point and parlaying the same functionality to the desktop/laptops, servers, and their respective end points to document storage repositories and databases.

In evaluating DLP applications, it is important to focus on the type of underlying engine that analyzes the data and then work up from that base. Next rate the ease of configuring the data categories and the ability to preload certain documents and document types. Look for a mature product with plenty of industry-specific references. Company stability and financial health should also come into play. Roadmaps of future offerings can give an idea of the features and functions coming in the next release. The relationship with the vendor is an important requirement to make sure that the purchase and subsequent implementation goes smoothly. The vendor should offer training that empowers the IT organization to be somewhat self-sustaining instead of having to go back to the vendor every time a configuration needs to be implemented. The vendor should offer best practices that other customers have used to help with quick adoption of policies. This allows for an effective system that will improve and lower the overall risk profile of the organization.

Analyst briefings about the DLP space can be found on the Internet for free and can provide an unbiased view from a third party of things that should be evaluated during the selection process.

10. Conclusion

DLP is an important tool that should at least be evaluated by organizations that are looking to protect their employees, customers, and stakeholders. An effectively implemented DLP application can augment current security safeguards. A well thought out strategy for a DLP application and implementation should be designed first before a purchase. All parts of the organization are likely to be impacted by DLP, and IT should not be the only organization to evaluate and create policies. A holistic approach will help foster a successful implementation that is supported by the DLP vendor and other departments, and ultimately the employees should improve the data risk profile of an organization. The main goal is to keep the brand name and reputation of the organization safe and to continue to operate with minimal data security interruptions. Many types of DLP approaches are available in the market today; picking the right vendor and product with the right features and functions can foster best practices, augment already implemented employee training and policies, and ultimately safeguard the most critical data assets of the organization.

“Guilty plea in trade secrets case,” Department of Justice Press Release, February 15, 2007.

“SEC EDGAR filing information form 8-K,” TJX Companies, Inc., February 20, 2008.

“GAO-07-737 personal information: Data breaches are frequent, but evidence of resulting identity theft is limited; however, the full extent is unknown,” General Accounting Office, June 2007.

“Portions of this production are provided courtesy of PCI Security Standards Council, LLC (“PCI SSC”) and/or its licensors © 2007 PCI Security Standards Council, LLC. All rights reserved. Neither PCI SSC nor its licensors endorses this product, its provider or the methods, procedures, statements, views, opinions or advice contained herein. All references to documents, materials or portions thereof provided by PCI SSC (the “PCI Materials”) should be read as qualified by the actual PCI Materials. For questions regarding the PCI Materials, please contact PCI SSC through its Web site at https://www.pcisecuritystandards.org.”

Wikipedia contributors, “Sarbanes-Oxley Act,” Wikipedia, Wednesday, 2008-05-14 14:31 UTC, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarbannes_Oxley_Act.

Figures 43.1, 43.2 (a-c), and 43.3 (a-b), inclusive of the Vericept trademark and logo, are provided by Vericept Corporation solely for use as screenshots herein and may not be reproduced or used in any other way without the prior written permission of Vericept Corporation. All rights reserved.

![]()

![]()