WEB-APPENDIX D

CREDIT RISK

Investors in corporate debt obligations are exposed to credit risk. There are two types of credit risk: default risk and downgrade risk. We discuss each in this appendix. In addition, we discuss instruments that allow for the transfer of credit risk.

D.1 DEFAULT RISK

Default risk is the risk that the issuer will fail to satisfy the terms of an obligation with respect to the timely payment of interest and repayment of the amount borrowed. Large institutional investors employ specialists (called credit analysts) to carry out credit analysis; however, often it is too costly and time-consuming to assess every issuer in every debt market. Therefore, individual investors rely on analysis performed by nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (popularly referred to as rating agencies) that perform credit analysis of issues and issuers and express their conclusions in the form of a credit rating. The three largest rating agencies are Moody's Investors Service, Standard & Poor's Corporation, and Fitch Ratings.

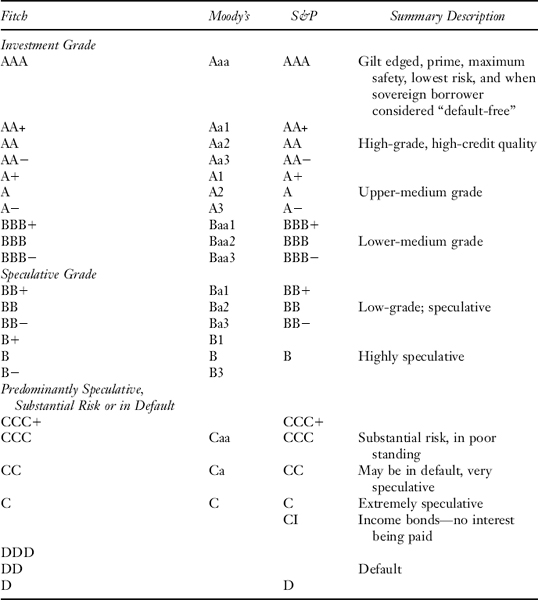

A credit rating is a formal opinion given by a rating agency of the default risk faced by investing in a particular issue of debt securities. For long-term debt obligations, a credit rating is a forward-looking assessment of the probability of default and the relative magnitude of the loss should a default occur. For short-term debt obligations, a credit rating is a forward-looking assessment of the probability of default. Table D.1 shows the long-term debt ratings of the three major rating agencies.

Corporate bond issues that are assigned a rating in the top four categories are referred to as investment-grade bonds. Bond issues that carry a rating below the top four categories are referred to as noninvestment-grade bonds or more popularly as high-yield bonds or junk bonds. Thus, the bond market can be divided into two sectors: the investment-grade sector and the noninvestment-grade sector. Distressed debt is a sub-category of noninvestment-grade bonds. These bonds may be in bankruptcy proceedings, in default of coupon payments, or in some other form of distress.

TABLE D.1 SUMMARY OF LONG-TERM BOND RATING SYSTEMS AND SYMBOLS

D.1.1 The Bankruptcy Process and Creditor Rights

Every developed country has laws that govern how the bankruptcy of borrowers (debtors) will be handled in the legal system. LaPorta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny (1997) show both the legal rules protecting investors and the quality of the enforcement of the rules by the courts are important in the development of a country's equity and debt markets.

In the United States, the bankruptcy law is part of the Title 11 of the United States Bankruptcy Code. Although states may not regulate bankruptcy, they are permitted to establish laws that govern other aspects of the debtor-creditor relationship. There are 94 federal judicial districts that handle bankruptcy matters. In almost all of the 94 districts, bankruptcy cases are filed in the bankruptcy court.

There are rules governing bankruptcy of individuals and those of corporations. Our focus is on the latter. A bankruptcy petition can be filed either by the corporation itself, in which case it is called a voluntary bankruptcy, or by its creditors, in which case it is called an involuntary bankruptcy. When a corporation files for protection under the bankruptcy act, it generally becomes a “debtor in possession” (DIP) and management continues to operate its business under the supervision of the bankruptcy court.

A corporation can either be liquidated or reorganized. In a liquidation, operations are ceased and all corporate assets are distributed to the holders of claims. No corporate entity survives after the liquidation is completed. In contrast, in a reorganization a new corporate entity emerges. Some holders of claims against the bankrupt corporation receive cash in exchange for their claims, while some may receive new securities in the corporation that results from the reorganization, and others may receive a package that includes cash and new securities in the resulting corporation.

The bankruptcy act gives management of a bankrupt corporation the time to decide which alternative to select—liquidation or reorganization—and then to formulate the plan to accomplish either decision. Time is allowed because when a corporation files for bankruptcy, the act grants the corporation protection from creditors who seek to collect their claims. Some argue that creditors receive a higher value in reorganization than they would in liquidation, in part because of the costs associated with liquidation.1

The bankruptcy act consists of fifteen sets of rules covering particular types of bankruptcy and referred to as “chapters.” We will focus on two chapters: Chapter 7 bankruptcies that deal with corporate liquidation and Chapter 11 that deals with corporation reorganization.

D.1.2 Absolute Priority Rule

In a bankruptcy, holders of corporate claims are to receive distributions based on the absolute priority rule to the extent assets are available. The absolute priority rule is the principle that creditors are to receive proceeds from the liquidation of assets based on what they bargained for when they negotiated with the corporation. That is, senior creditors are paid in full before junior creditors are paid anything. For both secured creditors and unsecured creditors, the absolute priority rule guarantees their seniority to equity holders.

In corporate liquidations, the absolute priority rule generally holds. However, there are numerous empirical studies, as well as casual observation, that support the view that in corporate reorganizations, absolute priority is not strictly upheld by bankruptcy courts and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).2 Studies of actual reorganizations report that the violation of absolute priority is the rule rather than the exception.3

The failure of the courts to strictly adhere to absolute priority has implications for the firm's capital structure decision. In a reorganization, equity claimants might receive some cash and new securities even if all the debt claimants are not paid in full. This has implications for the view in financial economics that the firm is effectively owned by the creditors who sold the shareholders a call option on the firm's assets. If deviations from the absolute priority rule are typical and allow stockholders to participate in corporate asset while debtor claims are not completely satisfied, this view is not sustainable.4

Fabozzi, Howe, Makabe, and Sudo (1993) examine the degree of violation of the absolute priority rule among secured creditors, unsecured creditors, and equity holders, as well as among various types of debt and equity securities. They also provide evidence on which asset class bears the cost of violations of absolute priority, and an initial estimate of total distributed value relative to liquidation value. They find that unsecured creditors bear a disproportionate cost of reorganization, and that more senior unsecured creditors may bear a disproportionate cost relative to the junior unsecured creditors, while equity holders often benefit from violations of absolute priority.

The following hypotheses have been proffered to explain why the violation from absolute priority is observed in a reorganization:

- According to the incentive hypothesis, the longer the negotiation process among all the claimants, the lesser the amount distributed to them because of the higher implicit and explicit costs associated with bankruptcy (costs of financial distress). To understand why, the reorganization process needs to be understood. A committee representing the various claim holders is appointed in a reorganization. The committee's purpose is to formulate a plan for reorganizing the company. To be adopted, this plan must be approved by specified numbers of all classes of interests—debt and equity—and this bargaining process is anticipated to be lengthy. The longer the negotiation process among the parties, the greater the risk that the company will be operated in a manner not in the best interest of the creditors, resulting eventually smaller distributions to them. For this reason, creditors often convince equity holders to accept the plan by offering to distribute some value to them.

- The recontracting process hypothesis, according to Baird and Jackson (1988), seeks to explain violations to absolute priority as a result of the recontracting process between stockholders and senior creditors that gives recognition to the ability of management to preserve value on behalf of stockholders.

- According to the stockholders’ influence on reorganization plan hypothesis, the firm's creditors are less informed about the firm's economic operating conditions than its management. Because the distribution to creditors in the reorganization plan depends on the valuation by the firm, creditors without perfect information suffer the loss, according to Bebchuk (1988). Management, as noted by Wruck (1990), generally has a better understanding than creditors or stockholders about a firm's internal operations, while creditors and stockholders can have better information about industry trends. Management may therefore use its superior knowledge to present the data in a manner that reinforces its position.

- The strategic bargaining process hypothesis asserts that due to the increasing complexity of firms declaring bankruptcy, the negotiating process during the reorganization process results in an even higher incidence of violations of the absolute priority rule. The likely outcome is further supported by the increased number of official committees in the reorganization process as well as the increased number of financial and legal advisors.

D.1.3 Default and Recovery Rates

There is a good deal of research published on default rates by rating agencies and academicians. From an investment perspective, default rates by themselves are not of paramount significance: It is perfectly possible for a portfolio of corporate bonds to suffer defaults and to outperform Treasuries at the same time, provided the yield spread of the portfolio is sufficiently high to offset the losses from defaults. Furthermore, because holders of defaulted bonds typically recover a percentage of the face amount of their investment, the default loss rate can be substantially lower than the default rate.

The default loss rate is defined as follows:

Default loss rate = Default rate × (100% − Recovery rate)

For instance, a default rate of 5% and a recovery rate of 30% means a default loss rate of only 3.5% (70% of 5%).

Therefore, focusing exclusively on default rates merely highlights the worst possible outcome that a diversified portfolio of corporate bonds would suffer, assuming all defaulted bonds would be totally worthless.

There have been several studies of default rates, particularly for high-yield corporate bonds, and the reported findings at times appear to be significantly different.5 The differences in the reported default rates are due to the different approaches used by researchers to measure default rates. As explained by Cheung, Bencivenga, and Fabozzi (1992), the differences in reported default rates are not as great as they might first appear once methodologies employed in these studies are standardized.

Several studies have found that the recovery rate is closely related to the bond's seniority. However, seniority is not the only factor that affects recovery values. In general, recovery values vary with the types of assets, the competitive conditions of the firm, and the economic environment at the time of bankruptcy. In addition, recovery rates will also vary across industries. For example, some manufacturing companies such as petroleum and chemical companies have assets with a high tangible value, such as plant, equipment, and land. These assets usually have a significant market value, even in the event of bankruptcy. In other industries, however, a company's assets have less tangible value, and bondholders should expect low recovery rates.

To understand why recovery rates might vary across industries, consider two extreme examples: a software company and an electric utility. In the event of bankruptcy, the assets of a software company will probably have little tangible value. The company's products will have a low liquidation value because of the highly competitive and dynamic nature of the industry. The company's major intangible asset, its software developers, may literally disappear as employees move to jobs at other companies. In general, in industries that spend heavily on research and development and in which technological changes are rapid, a company's liquidation value will decline sharply when its products lose their competitive edge. In these industries, bondholders can expect to recover little in the event of default. At the other extreme, electric utility bonds will likely have relatively high recovery values. The assets of an electric company (e.g., generation, transmission, and distribution) usually continue to generate a stream of revenues even after a bankruptcy. In most cases, a bankruptcy of a utility can be resolved by changing the company's capital structure rather than by liquidating its assets. In addition, regulators have a vested interest in maintaining the company as a going concern—no one likes to see the lights turned off.

D.2 DOWNGRADE RISK

Once a credit rating is assigned to a debt obligation, a rating agency monitors the credit quality of the issuer and can reassign a different credit rating. An improvement in the credit quality of an issue or issuer is rewarded with a better credit rating, referred to as an upgrade; a deterioration in the credit rating of an issue or issuer is penalized by the assignment of an inferior credit rating, referred to as a downgrade. The actual or anticipated downgrading of an issue or issuer increases the credit spread and results in a decline in the price of the issue or the issuer's bonds. This risk is referred to as downgrade risk and is closely related to credit spread risk. A rating agency may announce in advance that it is reviewing a particular credit rating, and may go further and state that the review is a precursor to a possible downgrade or upgrade. This announcement is referred to as “putting the issue under credit watch.”

D.2.1 Rating Migration (Transition) Table

The rating agencies periodically publish, in the form of a table, information about how issues that they have rated change over time. This table is called a rating migration table or rating transition table. The table is useful for investors to assess potential downgrades and upgrades. A rating migration table is available for different lengths of time. Table D.2 shows a hypothetical rating migration table for a one-year period. The first column shows the ratings at the start of the year, and the first row shows the ratings at the end of the year.

Let's interpret one of the numbers. Look at the cell where the rating at the beginning of the year is AA and the rating at the end of the year is AA. This cell represents the percentage of issues rated AA at the beginning of the year that did not change their rating over the year. That is, there were no downgrades or upgrades. As can be seen, 92.75% of the issues rated AA at the start of the year were rated AA at the end of the year. Now look at the cell where the rating at the beginning of the year is AA and at the end of the year is A. This shows the percentage of issues rated AA at the beginning of the year that was downgraded to A by the end of the year. In our hypothetical one-year rating migration table, this percentage is 5.07%. One can view this figure as a probability. It is the probability that an issue rated AA will be downgraded to A by the end of the year.

TABLE D.2 HYPOTHETICAL ONE-YEAR RATING MIGRATION TABLE

A rating migration table also shows the potential for upgrades. Again, using Table D.2, look at the row that shows issues rated AA at the beginning of the year. Looking at the cell shown in the column AAA rating at the end of the year, there is the figure 1.60%. This figure represents the percentage of issues rated AA at the beginning of the year that were upgraded to AAA by the end of the year.

In general, the following holds for actual rating migration tables. First, the probability of a downgrade is much higher than for an upgrade for investment-grade bonds. Second, the longer the migration period, the lower the probability is that an issuer will retain its original rating. That is, a one-year rating migration table will have a lower probability of a downgrade for a particular rating than a five-year rating migration table for that same rating.

D.3 CREDIT RISK TRANSFER MECHANISMS

There are several credit risk transfer (CRT) vehicles that have made it easier for market participants to reallocate large amounts of credit risk from the financial sector to the nonfinancial sector of the capital markets. The development of the derivatives markets prior to 1990 provided financial institutions with efficient vehicles for the transfer of interest rate, price, and currency risks, as well as enhancing the liquidity of the underlying assets. However, it is only since the late 1990s that the market for the efficient transfer of credit risk has developed.

The most obvious way for a financial institution to transfer the credit risk of a loan it has originated is to sell it to another party. Loan covenants typically require that the obligor be informed of the sale. The drawback of a sale in the case of corporate loans is the potential impairment of the originating financial institution's relationship with the obligor of the loan sold. Syndicated loans, described in web-Appendix B, overcome the drawback of an outright sale because banks in the syndicate may sell their loan shares in the secondary market. The sale may be through an assignment or through participation. While the former mechanism for a syndicated loan requires the approval of the obligor, the latter does not since the payments are merely passed through to the purchaser, and therefore the obligor need not know about the sale.

Another form of CRT vehicle developed in the 1980s is securitization. In a securitization, a financial institution that originates loans pools them and sells them to a special-purpose entity (SPE). The SPE obtains funds to acquire the pool of loans by issuing securities. Payment of interest and principal on the securities issued by the SPE is obtained from the cash flow of the pool of loans. While the financial institution employing securitization retains some of the credit risk associated with the pool of loans, the majority of the credit risk is transferred to the holders of the securities issued by the SPE.

Two more recent developments for transferring credit risk are credit derivatives and collateralized debt obligations (CDOs). For financial institutions, credit derivatives allow the transfer of credit risk to another party without the sale of the loan. A CDO is an application of securitization technology in which the credit risk of a loan pool is divided into different categories called tranches. With the development of the credit derivatives market, CDOs can be created without the actual sale of a pool of loans to an SPE using credit derivatives. CDOs created using credit derivatives are referred to as synthetic CDOs.6 Since 2007, the CDO market has not seen any issuance and is not likely to make a comeback.

REFERENCES

Altman, Edward I. (1989). “Measuring Corporate Bond Mortality and Performance,” Journal of Finance 44: 909–922.

Altman, Edward I., and S. A. Nammacher. (1987). Investing in Junk Bonds. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Asquith, Paul, David W. Mullins, and E. D. Wolff. (1989). “Original Issue High Yield Bonds: Aging Analysis of Defaults, Exchanges, and Calls,” Journal of Finance 44: 923–952.

Baird, Douglas G., and Thomas H. Jackson. (1988). “Bargaining After The Fall and The Contours of The Absolute Priority Rule,” University of Chicago Law Review 55: 738–789.

Bebchuk, L. A. (1988). “A New Approach to Corporate Reorganizations,” Harvard Law Review 101: 775–804.

Bulow, J. I., and J. B. Shoven. (1978). “The Bankruptcy Decision,” Bell Journal of Economics 9, 2: 437–456.

Cheung, Rayner, Joseph C. Bencivenga, and Frank J. Fabozzi. (1992). “Original Issue High Yield Bonds: Total Returns and Historical Default Experience: 1977–1989,” Journal of Fixed Income 5: 58–76.

Fabozzi, Frank J., Jane Howe, Takashi Makabe, and Toshihide Sudo. (1993). “Evidence on the Distribution Patterns in Chapter 11 Reorganizations,” Journal of Fixed Income 6: 6–23.

Franks, Julius R., and Walter N. Torous. (1989). “An Empirical Investigation of U.S. Firms In Reorganization,” Journal of Finance 44: 747–769.

Jackson, Thomas H. (1986). “Of Liquidation, Continuation, and Delay: An Analysis of Bankruptcy Policy and Nonbankruptcy Rules,” American Bankruptcy Law Journal 60: 399–428.

Jensen, Michael C. (1989). “Eclipse of the Public Corporation,” Harvard Business Review 89: 61–62.

Kender, M. T. and G. Petrucci. (2003). “Altman Report on Defaults and Returns on High Yield Bonds: 2002 in Review and Market Outlook,” Salomon Smith Barney, February 5.

LaPorta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. (1997). “Legal Determinants of External Finance,” 52: 1131–1150.

Lucas, Douglas J., Laurie S. Goodman, and Frank J. Fabozzi. (2007). “Collateralized Debt Obligations and Credit Risk Transfer,” Journal of Financial Transformation, 20: 47–59.

Meckling, William H. (1977). “Financial Markets, Default, and Bankruptcy,” Law and Contemporary Problems 41: 124–177.

Miller, Merton H. (1977). “The Wealth Transfers of Bankruptcy: Some Illustrative Examples,” Law and Contemporary Problems 41: 39–46.

Warner, Jerome B. (1977). “Bankruptcy, Absolute Priority, and the Pricing of Risky Debt Claims,” Journal of Financial Economics 4: 239–276.

Weiss, Laurence A. (1990). “Bankruptcy Resolution: Direct Costs and Violation of Priority of Claims,” Journal of Financial Economics 17: 285–314.

Wruck, Karen H. (1990). “Financial Distress, Reorganization, and Organizational Efficiency,” Journal of Financial Economics 27: 419–444.

1 See Jensen (1989) and Wruck (1993).

2 See for example, Meckling (1977), Miller (1977), Warner (1977), and Jackson (1986).

3 See Franks and Torous (1989), Weiss (1990), and Fabozzi, Howe, Makabe, and Sudo (1993).

4 See Black and Scholes (1973). In the derivation of the pricing of risky debt, Merton (1974) assumes that absolute priority holds.

5 See Altman (1989), Altman and Nammacher (1987), Asquith, Mullins, and Wolff (1989), Kender and Petrucci (2003), and the 1984–1989 issues of High Yield Market Report: Financing America's Futures, published by Drexel Burnham Lambert, Inc.

6 For a discussion of the concerns of these new CRT vehicles raised by regulators, see Lucas, Goodman, and Fabozzi (2007).