3

CREATING WEALTH BY INVESTING IN PRODUCTIVE OPPORTUNITIES

In this chapter we study how management can invest in firms so as to create wealth and thus enhance individuals' satisfaction. We first study proprietary firms in which the owner and manager are the same person. Then we consider productive firms with many owners. In both cases the firms make investment and financing decisions that can augment the wealth positions of their owners.

We shall see that in a perfect capital market management can maximize the wealth of a firm's owners by using a rule called the market value rule. This rule requires management to make decisions that maximize the market value of the firms they operate. After studying the details of how market value is maximized, we conclude the chapter by stating important generalizations, called separation principles, that both define the task of financial management and provide insight into how that task can best be performed.

3.1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL FIRM—PRODUCTION AND INVESTMENT DECISIONS

A firm with a single owner-manager can be regarded as a wealth-creating device capable of increasing its owner's well-being so long as the firm is properly operated. Proper operation means setting production and financing decisions in such a way as to maximize the owner's wealth. We begin by assuming the entrepreneur has knowledge of a production technology. An initial supply of resources is also available that can either be sold for cash or used in a productive process whose outputs are sold for cash. At first we do not worry about where the entrepreneur's original resources stem from, but later we consider what might be done if the entrepreneur has a marketable product and no initial resources whatever.

3.1.1 The Entrepreneur's Opportunities

As in the previous chapter we continue to consider two points in time. The problem we now face is how to represent the entrepreneur's opportunity set, given that some resources are owned and can be used in productive activity. There are a large number of different sorts of productive opportunities that appear to be different but are actually the same when regarded in terms of opportunity sets. Such diverse activities as storing a commodity at time 1 for sale at time 2 and the operation of a farm or manufacturing firm both have similar characteristics when depicted in terms of the productive opportunities they represent.

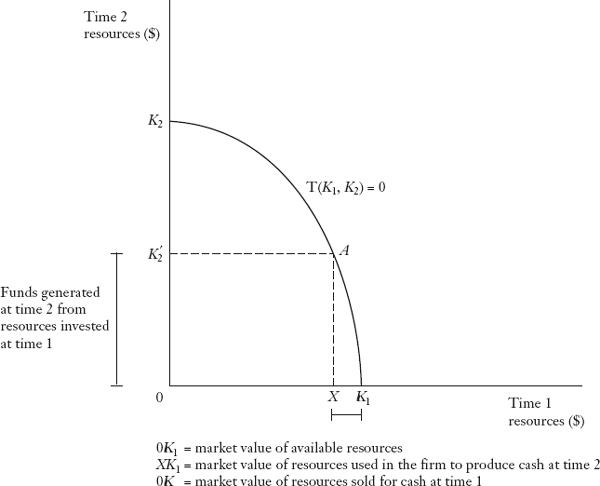

Regardless of which kind of productive opportunity we are considering, it can be represented by a transformation curve having the general form T(K1, K2) = 0, where K1 represents the dollar value of funds invested in the firm at time 1 and K2 the dollar value of funds generated at time 2. The funds generated derive from using the resources and technology available at time 1 to produce goods that are then sold at time 2. The transformation curve is assumed to reflect efficient use of funds in the sense that the capital investment is put to its best possible use; no resources are wasted by the rational entrepreneur.

We shall assume that the transformation curve has the form shown in Figure 3.1, where 0K1 represents the current market value of initial resources, which may either be used in productive opportunities or sold for cash. The meaning of the transformation curve may be understood by considering point A, which represents the strategy of selling 0X of initial resources immediately and investing XK1 in the productive opportunity at time 1. The amount of funds generated at time 2 from the investment XK1 is denoted by 0K2;0K2 indicates the time 2 yield if all resources were to be invested.

The slope of a transformation curve may be interpreted as indicating the firm's marginal rate of return, because it shows the amount realized at time 2 from an increment of funds invested at time 1. Note that the shape of the transformation curve in Figure 3.1 implicitly assumes that the marginal rate of return falls steadily as the level of investment increases. (Increasing investment is shown by moving from K1 to the left in the figure.) The declining slope of the transformation curve of Figure 3.1 can result from either or both of two phenomena. On the one hand, the demand curve for the firm's output may be downward sloping, so that output price must decline if more output is to be sold.1 In this case the transformation curve will have a decreasing slope as long as average production costs do not fall as fast as output price. On the other hand, the marginal cost of production may rise due to diminishing marginal physical product of invested capital. This is sufficient to cause the transformation curve to have a decreasing slope even if average sales revenue is constant, and will of course be sufficient if average sales revenue is declining. In either case, the rate of return on invested capital will decline as increasing amounts of capital investment are undertaken.

The firm's productive opportunity set is the region enclosed by the line 0K1K2. However, since the firm's owner is concerned with making the most of available resources, the relevant portion of the productive opportunity set is the transformation curve K1K2. We next show how the owner chooses a combination of financial and productive opportunities to maximize initial wealth. For by maximizing initial wealth, the entrepreneur also maximizes the present value of available consumption opportunities, thus becoming as well off as possible given the circumstances faced. These matters may perhaps best be illustrated by some examples.

FIGURE 3.1 PRODUCTIVE OPPORTUNITIES

Suppose at time 1 a farmer can sell 1,000 units of a commodity (e.g., wheat), which is now in storage. The current price of wheat is $1.00 per unit. Alternatively, the farmer can wait until time 2 and sell the 1,000 units at $1.30 per unit. Assuming no spoilage and no storage charges, the situation implies a linear transformation curve as shown in Figure 3.2. Note that in such a case the farmer will either sell all the commodity at time 1 or keep it all until time 2 (unless the market opportunity line has a slope exactly equal to the transformation curve, in which case differing amounts may be sold at either time 1 or time 2 without affecting wealth). As shown in the diagram, if market rates of interest are less than 30%, the market opportunity lines are less steeply sloped than the transformation curve, and the commodity should be stored for sale at time 2. In this case the farmer can borrow at the market rate to finance current consumption, repaying the loan at time 2 from the proceeds of the commodity then sold. In this way the farmer is better off than if the commodity is completely sold at time 1, as the figure also shows.2 If interest rates exceed 30%, the commodity should be sold at time 1, and any funds not expended on consumption should be reinvested.

FIGURE 3.2 COMMODITY STORAGE EXAMPLE

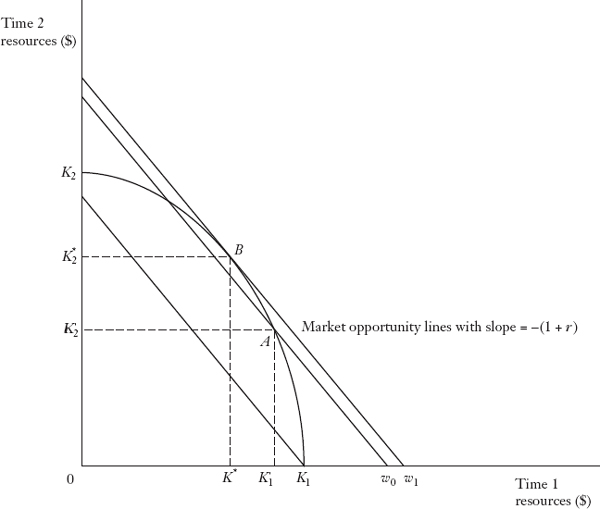

Let us now consider a second example, where productive opportunities are represented by a transformation curve of the nonlinear type first introduced. Referring to Figure 3.3, if an individual immediately liquidates the initial endowment of resources 0K1, an initial cash position (available for either consumption or investment at time 1) with a value of K1 is obtained. This wealth can be converted into time 1 and time 2 cash flows as indicated by the straight line of slope −(1 + r) passing through K1. If, however, the individual liquidates only a portion of initial resources (0K1) and uses the rest (K′1K1) for investment in some productive activity, we can represent the new set of attainable combinations by a straight line of slope −(1 + r) passing through the points w0 and A. Note that, since w0 is an intercept on the time 1 axis, it represents wealth exceeding the value of the initial resources. Wealth has increased because the individual can earn a higher than market rate of return by investing some of the initially available resources in the firm.

By repeated application of the foregoing reasoning, we discover the investment policy that dominates all others is represented by point B, where the straight line with slope −(1 + r) is exactly tangent to the productive opportunity set. This policy calls for liquidating ![]() and investing

and investing ![]() to obtain an initial wealth of w1. The important implication of the tangency condition is that the marginal rate of return is exactly equal to the market rate of interest, as may be seen by noting that at point B the slope of the transformation curve (one plus the marginal rate of return) is equal to the slope of the highest attainable market opportunity line (one plus the market interest rate). The purpose of reaching this highest market opportunity line is, of course, to enable the individual to attain the highest possible initial wealth, a value indicated by w1. Thus, a policy of investing funds in the firm until their rate of return falls to equality with the market rate of interest is a policy that maximizes the entrepreneur's initial wealth.

to obtain an initial wealth of w1. The important implication of the tangency condition is that the marginal rate of return is exactly equal to the market rate of interest, as may be seen by noting that at point B the slope of the transformation curve (one plus the marginal rate of return) is equal to the slope of the highest attainable market opportunity line (one plus the market interest rate). The purpose of reaching this highest market opportunity line is, of course, to enable the individual to attain the highest possible initial wealth, a value indicated by w1. Thus, a policy of investing funds in the firm until their rate of return falls to equality with the market rate of interest is a policy that maximizes the entrepreneur's initial wealth.

FIGURE 3.3 PRODUCTIVE AND CAPITAL MARKET OPPORTUNITIES

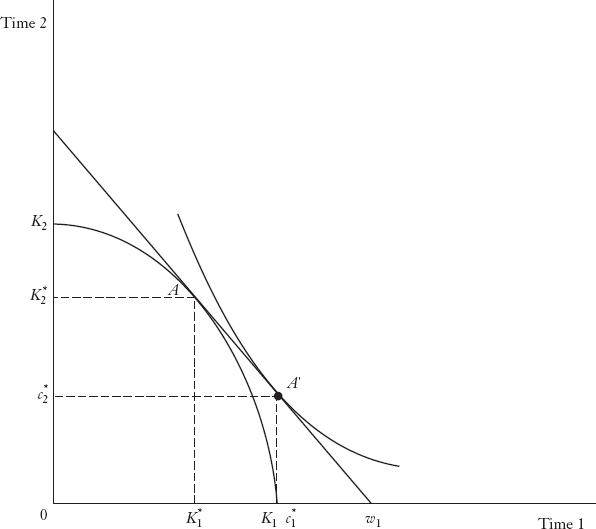

We can now consider simultaneous choice of both production-investment and consumption decisions by adding indifference curves to diagrams like Figure 3.3. The preferred consumption choices are indicated by point A* in Figure 3.4, which indicates that to maximize satisfaction the entrepreneur should first maximize initial wealth. This involves (1) liquidating and withdrawing ![]() of the initial resources and (2) investing the remaining

of the initial resources and (2) investing the remaining ![]() in the productive opportunity at time 1 to yield proceeds of

in the productive opportunity at time 1 to yield proceeds of ![]() at time 2. Then the wealth w1 so generated is allocated to consumption in the two periods. This is done by (3) consuming

at time 2. Then the wealth w1 so generated is allocated to consumption in the two periods. This is done by (3) consuming ![]() at time 1, borrowing

at time 1, borrowing ![]() dollars to finance the gap between desired consumption and the proceeds of resources sold for cash, and (4) consuming

dollars to finance the gap between desired consumption and the proceeds of resources sold for cash, and (4) consuming ![]() at time 2, repaying the loan, plus interest,

at time 2, repaying the loan, plus interest, ![]() , from the proceeds of the productive opportunity established by the initial investment.

, from the proceeds of the productive opportunity established by the initial investment.

FIGURE 3.4 JOINT CHOICE OF PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION DECISIONS

By virtue of combining borrowing in the capital market with the productive opportunity this entrepreneur is clearly better off than if either the productive or the market opportunity were faced alone. Note also that once the individual has determined the value of investment, ![]() , no more can be done to increase total wealth. From that point on, all the entrepreneur can do is determine the most satisfactory consumption pattern having a present value that is also equal to the w1 generated from following an optimal investment policy.

, no more can be done to increase total wealth. From that point on, all the entrepreneur can do is determine the most satisfactory consumption pattern having a present value that is also equal to the w1 generated from following an optimal investment policy.

The decision process can be viewed as encompassing two distinct steps:

| Step 1: | Choose the optimum production by equating the marginal rate of return on investment with the market required rate of return. |

| Step 2: | Choose the optimum consumption pattern by borrowing or lending in the capital market until the consumer's subjective rate of time preference equals the market rate of return. |

FIGURE 3.5 ENTREPRENEUR BORROWS INITIAL CAPITAL

This separation of investment and consumption decisions is sometimes referred to as the Fisher separation theorem.3 We discuss this principle's importance at greater length in Section 3.4.

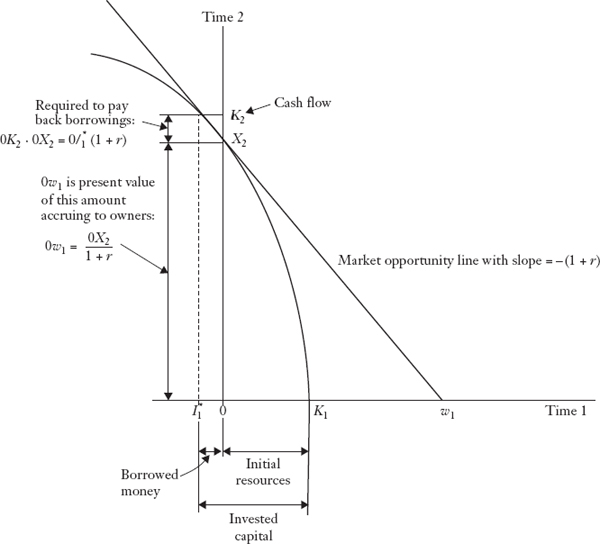

3.1.2 The Entrepreneur with No Initial Resources

Suppose we now consider an aspiring entrepreneur who has a marketable product and understands the necessary productive technology but has no resources to finance the undertaking. Would the entrepreneur be prevented from realizing the value of the technical possibilities? Under the assumptions of a perfect capital market, the answer is no. For, as Figure 3.5 shows, the entrepreneur with no initial resources will be able to go to the capital market at time 1 and borrow all the funds needed to finance production (![]() , to be paid back from the cash flow generated by production and received at time 2). Because the individual starts with no financial resources, the transformation curve is shown as emanating from the diagram's origin. As the amount

, to be paid back from the cash flow generated by production and received at time 2). Because the individual starts with no financial resources, the transformation curve is shown as emanating from the diagram's origin. As the amount ![]() is borrowed, it is shown as a negative amount. At time 2, the firm repays

is borrowed, it is shown as a negative amount. At time 2, the firm repays ![]() , leaving 0X2 accruing to the owner. The time 1 value of 0X2 is, of course, w1 as shown. Thus, we see that in a perfect capital market entrepreneurs with economically viable ideas can create wealth for themselves even though they do not initially have the funds to finance their ventures—ideas can have a marketable value that can be realized by borrowing from others.

, leaving 0X2 accruing to the owner. The time 1 value of 0X2 is, of course, w1 as shown. Thus, we see that in a perfect capital market entrepreneurs with economically viable ideas can create wealth for themselves even though they do not initially have the funds to finance their ventures—ideas can have a marketable value that can be realized by borrowing from others.

FIGURE 3.6 ENTREPRENEUR BORROWS SOME OF THE REQUIRED CAPITAL

We can also imagine circumstances in which the entrepreneur has some of the funds needed for investment but must borrow the balance. We represent this by appropriately positioning the transformation curve as shown in Figure 3.6. Note that in this case the increment to the entrepreneur's wealth K1w1 is the same irrespective of whether 0I* is borrowed and 0K1 invested or whether 0K1 is sold and the entire amount of I*K1 is borrowed. We conclude that in these circumstances the method of financing a productive investment is irrelevant to determining the value of the opportunity, a principle whose importance we shall consider later in some detail.

3.2 INVESTMENT DECISIONS MADE BY MANAGERS ON BEHALF OF OWNERS

Although the previous section provided worthwhile statements of optimal decision principles for proprietary firms (or entrepreneurial firms as we referred to them), business entities that are responsible for investing most of the funds put to work in an economy are corporations. (Some investing businesses are unincorporated entities with more than a single owner, but for simplicity in what follows, we shall refer only to corporations.) This fact leads us to consider two additional issues:

| Issue 1: | Corporations have many owners, and there is no reason to assume that the owners' preferences are all the same. |

| Issue 2: | The owners of a corporation do not make the operating decisions of the firm but rather hire professional managers and delegate decision-making power to these managers. |

No problems arise if the corporation can be managed to yield present values of owners' wealth that are exactly the same as if the owners were making the decisions themselves. For we know that w1 constitutes the only restriction on individuals' consumption decisions. That is, in a perfect capital market the corporation is regarded only as a means of generating wealth, because the present value of the dollar returns it generates is the only feature relevant to its owners. Even if the owners have different marginal rates of substitution between time 1 and time 2 consumption, in a perfect capital market the present value of initial wealth is the only thing constraining their consumption choices. Since this initial wealth is maximized when the market value of individuals' investments is maximized, in a perfect capital market managers (acting on behalf of the firms' stockholders) should maximize the market values of the firms they operate. For if the market value of a firm is maximized, so is the market value of any owner's proportional share of the firm's earnings.

3.2.1 Corporations and the Market Value Criterion

To see in greater detail that managers should employ the market value criterion in operating a productive firm, we reconsider the results of the previous section. An entrepreneur's optimal consumption, production, and financing decisions were characterized by the simultaneous satisfaction of two tangency conditions between:

- The transformation curve and the capital market opportunity line and

- The capital market opportunity line and an indifference curve.

The first condition can be satisfied without needing to know anything about the individual preferences characterizing the second condition. On the presumption that a professional manager is hired on the basis of technical competence (that is, knowledge of the firm's technology), such a person can determine a production plan that will maximize the market value of the firm by relating knowledge of the firm's rate of return on investment to the universally available information regarding the market rate of interest.

The next step in our argument is key to understanding much of the power of financial economic theory. Recall that market opportunity lines are lines of equal present value. Thus, when we instruct the manager to find a tangency between a transformation curve and a market opportunity line, this is equivalent (if returns always diminish with more investment) to maximizing the time 1 market value of cash withdrawals that current owners can realize from the firm. Hence, management following this prescription will maximize the combined wealth of the firm's current owners and also any individual owner's proportional interest in that sum.

The management of a corporation can leave consumption decisions to individuals because an individual's current wealth is the only constraint on consumption opportunities over time. The individual meets the second condition for the optimum through personal transactions in the capital market. In a perfect capital market any set of consumption choices with a given present value can be exchanged for any other set with the same present value. In particular, this implies that any set of consumption possibilities a stockholder can derive from a firm can be converted to a wealth that is equal to this present value. Thus, if any given management decision increases the stockholders' current wealth, the stockholders are unequivocally better off. Hence, a market-value-maximizing decision leaves every stockholder as well off as possible.

3.2.2 Maximizing Market Value Is Equivalent to Maximizing Profits

The market value criterion is actually more general than has been apparent so far. For when properly interpreted, the market value rule is also a rule that requires managers to maximize profits at each point in time. To see the equivalence between value maximization and properly interpreted profit maximization, consider the following example, which for the sake of greater generality also contemplates three points in time.

Let ![]() be the total amount invested in a firm at time 1, K2 be cash flow net of operating expenses at time 2, and K3 be cash flow net of operating expenses at time 3. Assume r is the market rate of interest in both periods. Then the firm's market value at time 1 is:

be the total amount invested in a firm at time 1, K2 be cash flow net of operating expenses at time 2, and K3 be cash flow net of operating expenses at time 3. Assume r is the market rate of interest in both periods. Then the firm's market value at time 1 is:

Now suppose the outlays for investment ![]() are all borrowed and that a loan repayment schedule is established requiring payment of principal and interest in amounts I2 and I3 at times 2 and 3 respectively such that:

are all borrowed and that a loan repayment schedule is established requiring payment of principal and interest in amounts I2 and I3 at times 2 and 3 respectively such that:

Such a schedule ensures, of course, that the lender receives the market rate of interest on the loan. Then we can write:

by substituting equation (3.2) into equation (3.1). Furthermore, if the loan repayments are just equal to economic depreciation, then K2 − I2 = π2 and K3 − I3 = π3 so that π2 and π3 are economic profits in the two periods. Hence, we can rewrite equation (3.3) as:

![]()

Therefore, maximizing the present value of all (properly interpreted) profits is the same as maximizing the market value of the firm.

The criteria of maximizing market value and of individually maximizing profits in each period are not equivalent when decisions can increase profits in some periods but reduce them in others. In such circumstances, correct decisions will certainly be made if they are made using the market value criterion. Moreover, even in this case a proper interpretation of profits in each period will still yield the result that their present value will be maximized. This issue is discussed at greater length in Chapter 6.

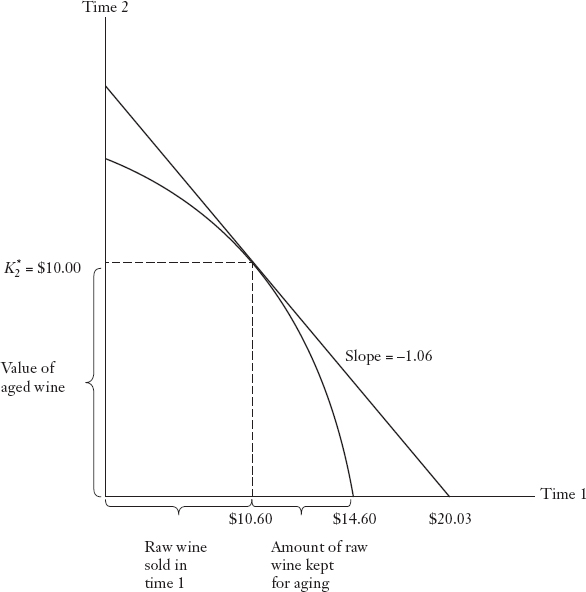

3.3 EXAMPLE: AGING WINE

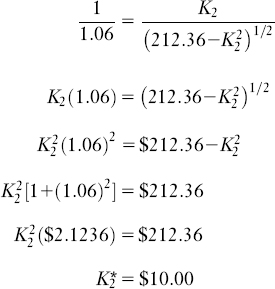

In this section we present a mathematical example as supporting detail for the graphical reasoning presented above. Consider the problem of a businessperson trying to decide whether to sell a product now or refine it further and sell it later at a higher price. For example, assume a vintner who is trying to maximize the market of initially available resources in the form of new wine either by selling the current vintage of wine at time 1 or aging it for sale at time 2. Let the market rate of interest be 6%.

The objective function of the vintner will be:

where K1 = value of new wine sold at time 1

K2 = value of aged wine sold at time 2

Assume the maximization is subject to ![]() , a transformation curve chosen for its mathematical tractability rather than for its interpretive realism. The transformation curve implies that the time 1 cash value of all the raw wine is ($212.36)½, or approximately $14.60.

, a transformation curve chosen for its mathematical tractability rather than for its interpretive realism. The transformation curve implies that the time 1 cash value of all the raw wine is ($212.36)½, or approximately $14.60.

Proceeding by substitution, we can rewrite equation (3.4) as:

Taking the derivative of equation (3.5) with respect to K2 and setting the result equal to zero, we obtain:

This step is equivalent to saying “choose a production plan such that the marginal rate of return equals the market rate of interest.” Rewriting equation (3.6), we obtain the following sequence of calculations:

therefore

![]()

and

![]()

This situation is shown graphically in Figure 3.7. Note the following: (1) The vintner has increased initial wealth (MV1) to $20.03 from the original $14.60 available by selling all the raw wine at time 1; (2) the vintner will employ wine in the aging process up to the point where the marginal rate of return on aging wine just equals the market rate of interest.

3.4 CONSEQUENCES FOR INVESTMENT AND FINANCING DECISIONS

The consequences of this chapter's theoretical investigation are of considerable importance to understanding financial decision making. Thus, we next summarize our four major findings along with two general principles that flow from them:

- The market-value-maximizing firm will invest up to the point where the marginal rate of return equals the market rate of interest. This is also consistent with long-run profit maximization when profits are correctly calculated. Note that the decisions involve determining how much to invest, that is, a matter of scale (or total capital budget4), rather than a simple accept reject assessment for a given project of fixed size.

- Determination of the total investment in a firm depends on two things: (1) the technology and the cash flow it yields and (2) the market rate of interest. Value is created when, on the average, the firm's rate of return exceeds the market rate of interest. Value is maximized when these last two rates are brought into equality by the final marginal amount of investment. Since the market rate of interest is the firm's cost of capital in a certainty world with a perfect capital market, value is maximized when funds are invested up to the point where the marginal rate of return falls to equal the firm's cost of capital.

- It does not matter whether the firm is owned by many stockholders or a single owner, since if the market value of the firm is maximized so is any stockholder's proportional interest in that market value.

- Whether the firm uses its own money (retained earnings) or external financing makes no difference. Under assumptions of certainty and a perfect capital market, all sources of financing have the same cost, the market rate of interest. This is true even for retained earnings, since the market rate of interest is the opportunity cost for those retained earnings.

Our last conclusion may be difficult for the practical-minded to accept because it is generally believed that in more complex situations than the one now being examined, the source of financing does make a difference and that optimal capital structures do exist. We emphasize that our present conclusion applies to a certainty world with a perfect capital market. But our finding is valuable nonetheless, because it gives us a hint as to what conditions (market imperfections) might render valid the belief that capital structure does indeed matter in certain kinds of practical circumstances. Indeed, when we later introduce market imperfections, our conclusions will not only approach those acceptable to conventional wisdom, but we shall know why there is truth in the old beliefs.

Finally, we note that while the market value criterion requires management to concern itself only with the technical aspects of production, managers are not computers. They may have their own preferences that may conflict with those of the stockholders. How can we ensure that the market value rule will be followed by such managers? While it is beyond the scope of our discussion at this point, the economic theory of agency is one way in which this problem can be approached (Chapter 20).

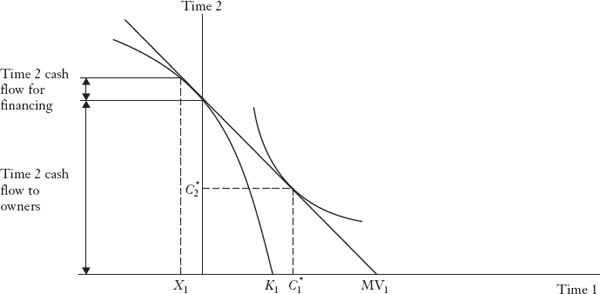

3.4.1 Separation of Operating and Financing Decisions

Given its production plans, in a perfect capital market a firm's financing of the investments needed to carry out these plans is a matter of indifference to its owners. That is, the market value of the firm is determined only by the cash flows it can generate and not by the source of funds used to finance those operations. This also means that the firm's cost of capital is independent of its financing sources. This separation principle follows from the fact that once the operating plans of the firm have been fixed (that is, once the point of tangency between the transformation curve and the market opportunity line has been found), it is irrelevant whether financing is from one source or another because the cost of any type of financing arrangement is the same and is equal to the market rate of interest.

The operational importance of the foregoing separation principle is that the firm's operating plans and the attendant investment decisions need not be considered simultaneously with decisions as to how to finance the investment. This is the same thing as saying that all investment decisions can be evaluated using the market rate of interest because this interest rate is the firm's cost of capital.5

FIGURE 3.8 SEPARATION OF OPERATING AND FINANCING DECISIONS

We show the separation of operating and financing decisions graphically in Figure 3.8. By an operating decision, we mean the decision to invest X1K1, which determines the amount of the firm's output it will produce and sell. By saying that financial decisions are separate from this operating decision we mean that if the existing owners of the firm originally had resources 0K1, the amount of those resources that they personally invest in the firm is irrelevant to the determination of its value. Properly operated, the firm is worth MV1. The existing owners can arrange any profile of cash withdrawals from the firm at times 1 and 2 as long as the profile has a present value equal to MV1. If the existing owners do not wish to provide the required investment funds X1K1, the funds can be raised in the capital market.

In a perfect capital market every economically viable proposition is always financed by some investor, and an outside investor always receives the market rate of interest on his investment. If the investors are the original owners, they receive a higher rate of return from investing in the firm. However, they value the cash flows so generated using the market rate of interest, because that is their opportunity cost. In other words, the firm's management creates value for the original owners by investing funds at rates that exceed, on average, the market rate of interest. But to determine how much wealth was created, the original owners discount the firm's cash flows at the market rate of interest.

3.4.2 Separation of Managers' and Owners' Decisions

The second major principle resulting from our findings is that there are no disparities between the goals of managers and owners as long as the firm's managers maximize the market value of the owners' investment in the firm. If the firm has only a single owner, an entrepreneur, we argued that the appropriate criterion for determining satisfaction is the time 1 value of the owner's consumption expenditures. But we also saw that the only constraint on the entrepreneur's consumption decisions is the market opportunity line, which is fixed by the value of initial wealth. Hence, the process of creating wealth can be delegated to a manager who need not know what the owner's consumption preferences are.

A similar result holds for multi-owner firms operating in a perfect capital market. The market value rule requires managers to maximize the current market value of the firm, subject to the technological constraints imposed by the transformation curve. Value maximization is all that managers can do for stockholders, irrespective of their preferences, because the market value of all investments is the owners' wealth, and wealth is the only constraint on owners' consumption decisions.

The importance of this result is that in order to act in the owners' best interests, the firm's managers need not have information about the owners' utility functions. The task of corporate management is thus to create wealth by finding productive opportunities with average rates of return exceeding the market rate of interest. Managers maximize this wealth using the market value rule, which says that market value is maximized by investing in the productive opportunity up to the point where the marginal rate of return declines to equality with the market rate of interest. The separation principle states that the market value rule impounds all the information with which managers need to be concerned.

FIGURE 3.9 SEPARATION OF MANAGERS' AND OWNERS'DECISIONS

To see the essence of this separation principle graphically, consider Figure 3.9. The separation principle says the firm's managers determine the optimal investment X1K1 and hence its market value MV1. In other words, the firm's managers determine the intercept MV1 of the owners' market opportunity line. If the firm has a single owner, the latter then decides what consumption standards, with a present value of MV1, are preferred; that is, the owner chooses a position on the market opportunity line. If the firm has many owners, a given owner is entitled to only some proportion of market value, say αMV1 (0 ≤ α ≤ 1). This then defines the market opportunity line along which that particular owner can move.

KEY POINTS

- In a perfect capital market, management can maximize the wealth of a firm's owners by using the market value rule. This rule requires management to make decisions aimed at maximizing the market value of the firms they operate.

- A firm with a single owner-manager (referred to as a proprietary firm) can be regarded as a wealth-creating device capable of increasing its owner's well-being if the owner sets production and financing decisions in such a way as to maximize the owner's wealth.

- The productive opportunity set of a proprietary firm is graphically depicted by a transformation curve that shows efficient use of funds. Efficiency means that the capital investment is put to its best possible use and there are no resources wasted by the rational entrepreneur. The slope of the transformation curve may be interpreted as indicating the firm's marginal rate of return.

- A management policy of investing funds until their rate of return falls to equality with the market rate of interest is a policy that maximizes the entrepreneur's initial wealth.

- Combining borrowing in the capital market with a productive opportunity results in an entrepreneur being better off than if either the productive or the market opportunity were faced alone.

- The owner's decision process can be viewed as encompassing two distinct steps: (1) selecting the optimum production by equating the marginal rate of return on investment with the market required rate of return and (2) selecting the optimum consumption pattern by borrowing or lending in the capital market until the consumer's subjective rate of time preference equals the market rate of return.

- The separation of investment and consumption decisions is sometimes referred to as the Fisher separation theorem.

- Unlike proprietary firms, managers of corporations are responsible for most of the funds invested in an economy. Corporations have many owners, and there is no reason to assume that the owners' preferences are all the same. The owners of a corporation do not make the operating decisions of the firm but rather hire professional managers and delegate decision-making power to these managers.

- In a perfect capital market, the market value of individuals' investment is maximized by managers acting on behalf of firms' stockholders. The managers will serve the stockholders' best interests if they maximize the market values of the firms they operate. If the market value of a firm is maximized, so is the market value of any owner's proportional share of the firm's earnings.

- In a perfect capital market, the separation of operating and financing decisions for a corporation still holds; that is, given its production plans, a firm's financing of the investments needed to carry out these plans is a matter of indifference to its owners.

- In a perfect capital market, the market value of the firm is determined only by the cash flows it can generate and not by the source of funds used to finance those operations. The task of management is to create wealth by finding productive opportunities with average rates of return exceeding the market rate of interest.

QUESTIONS

- What is meant by the market value rule?

- a. What is the transformation curve?

b. What is the interpretation of the slope of the transformation curve?

- What is meant by the Fisher separation theorem and its implications for financial decision making?

- Explain why the total investment that management should make for a firm depends on the cash flow that can be generated by the existing technology and the market rate of interest.

- Explain whether you agree or disagree with the following statement: Value is maximized when the market rate of interest exceeds the rate of return that can be earned by a firm on its invested funds.

- Under assumptions of certainty and a perfect capital market, explain why it makes no difference whether the firm uses its own money (retained earnings) or external financing.

- With respect to the separation principle, explain whether you agree or disagree with the following statement: The firm's operating plans and attendant investing and financing decision need not be considered simultaneously.

- What is the major finding regarding disparities between the goals of owners and managers that results from the separation principle?

- Consider the example in Section 3.3 but now assume that the market rate of interest is 10%. Graphically show the operating plan for the following two transformation curves:

- a. 3K1 + 2K2 = 30

b.

Using the transformation curve in part b, find the firm's optimal financing decision if the firm's initial resources at time 1 is:

c. 5

d. 0

e. Find the optimal consumption decision assuming the transformation curve in part b and further assuming that the only owner of the firm has the following utility function:

- a. 3K1 + 2K2 = 30

REFERENCES

Fisher, Irving. (1930). The Theory of Interest. New York: Macmillan.

1 The downward-sloping demand curve reflects finite elasticity of demand for the output and perhaps also diminishing marginal returns to advertising.

2 Incidentally, the diagram is not consistent with commodity market equilibrium. For in the present circumstances, commodity speculators will have an incentive to buy and hold the commodity, thus bidding up the price at time 1 until the transformation curve and market opportunity lines have equal slopes.

3 Because it first appears in Fisher (1930), Irving Fisher's insights have had a substantial impact on the contemporary economic theory of finance.

4 We discuss capital budgeting in Chapter 6.

5 Most capital expenditure decision criteria implicitly assume this separation principle holds in that they talk first about choosing a criterion, such as the present value of cash flows, and then using the cost of capital in order to determine the present value.