5

FIRM FINANCING DECISIONS IN A PERFECT CAPITAL MARKET

Afirm's managers invest in new plant and equipment to generate additional revenues and income. Earnings generated by the firm belong to the owners and can either be paid to them or retained within the firm. The portion of earnings paid to the firm's owners is referred to as dividends; the portion retained within the firm is referred to as retained earnings. The owners’ investment in the company is referred to as owners’ equity or, simply, equity.

If earnings are plowed back into the company, the owners expect it to be invested in projects that will enhance the firm's value, and hence, the value of the owners’ equity. Consequently, one way to pay for new investments is to use some of the previously retained earnings. But earnings may not be sufficient to support all profitable investment opportunities, and if so, management must either forego the investment opportunities or raise additional capital. New capital can be raised by borrowing, by selling additional ownership interests, or both. Borrowing can be in the form of bank loans or the issuance of debt obligations such as bonds. When we discuss additional ownership interests, we will usually assume that additional ordinary shares of common stock are issued.1

Decisions about how the firm should be financed, whether with debt or equity, are referred to as capital structure decisions. In this chapter, we explain both the basic issues associated with capital structure decisions and how corporate management should choose a capital structure in a perfect capital market. The principal issue faced by management is whether there is a capital structure that maximizes the firm's value, referred to as an optimal capital structure. This chapter examines a theory, known as the Modigliani-Miller theory, explaining the influence of capital structure on firm value in the context of a perfect capital market. In a perfect capital market and the absence of corporate taxation, the value of the firm will not change as capital structure is altered: The Modigliani-Miller theory argues that capital structure is irrelevant.

The demonstration in this chapter should be regarded as a first step in disentangling the effects of capital structure choice.2 In Part VII, we find that capital market imperfections can provide reasons for capital structure to matter, and provide analyses of the effects of capital structure decisions in a world of imperfect capital markets.

5.1 DEBT VS. EQUITY

A firm's capital structure is some mix of three sources: debt, equity already accumulated (from previous equity issues or from accumulated earnings), and new equity. If management elects to finance the firm's operations with debt, the creditors (lenders) expect the interest and principal—fixed, legal commitments—to be paid back as promised. Failure to pay may result in legal actions by the creditors. If the firm finances its operations with equity, the owners expect a return in the form of dividends, an appreciation of the value of their equity interest (i.e., capital gain), or, as is most likely, some combination of both.3

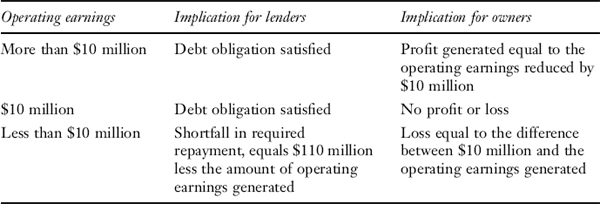

Returning to the effects of a debt issue, suppose a firm's management elects to borrow $100 million for one year at an interest rate of 10%. By doing so, the firm is promising to repay the $100 million plus $10 million in interest in one year. That is, satisfying the debt obligation means that $110 million must be paid. Consider the following three possible outcomes for the firm's operating earnings (i.e., earnings from operations before interest expense) generated by the $100 million invested and any returns on it, and the associated consequences for lenders and owners.

As indicated, if management can invest the amount borrowed so as to realize both a return of the invested capital—$100 million—plus operating earnings in excess of the $10 million the firm must pay in interest (the cost of the funds), the company keeps all the profits. But if the investment generates operating earnings of $10 million or less for the firm, the lender still gets either $10 million or whatever the operating earnings happen to be.

The foregoing example illustrates the basic idea behind financial leverage—the use of financing that has fixed, but limited, payments. If the company has abundant earnings relative to the debt payments that must be made, the owners reap all that remains of the earnings after the creditors have been paid. If earnings are low relative to the debt payments that must be made, the creditors still must be paid what they are due, possibly leaving the owners nothing. Failure to pay interest or principal as promised may lead to financial distress. Financial distress is the condition where management makes decisions under pressure to satisfy its legal obligations to its creditors—decisions that may not be in the best interests of the company's owners. Although management may and often does choose to make dividend payments to shareholders, with equity financing there is no legal obligation to do so. Furthermore, under U.S. tax law, interest paid on debt is deductible for tax purposes, whereas dividend payments are not tax deductible.

One measure of the extent to which debt figures in the capital structure is the debt ratio:

Debt ratio = Par value of debt/Market value of equity

The greater the debt ratio, the greater the use of debt relative to equity financing. Another measure is the debt-to-assets ratio, which is the extent to which the firm's assets are financed with debt:

Debt-to-assets ratio = Par value of debt/Market value of total assets

This is the proportion of debt in a company's capital structure.

5.2 CAPITAL STRUCTURE AND FINANCIAL LEVERAGE

Capital structure decisions can affect the risks stemming originally from the company's business decisions. As explained in Section 5.1, debt and equity financing create different types of obligations for the company. The concept of leverage plays a role in affecting the company's financial risk because leverage amplifies the effects of outcomes, good or bad. The fixed and limited nature of a debt obligation affects the risk of the earnings available for distribution to the owners. Consider a firm that has $20 million of assets, all financed with equity. We refer to such a firm as “100% equity financed” or “unlevered.” Suppose that there are 1 million shares of stock of this firm outstanding, valued at $20 per share. In this case, the equity is $20 million, equal to the value of the assets, and the debt is zero.

Suppose further that the firm's management (1) has identified investment opportunities requiring $10 million of new funds and (2) can raise the funds in one of the following three ways:

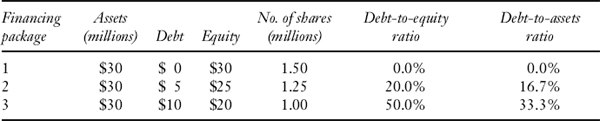

For each financing package, the resulting post-financing capital structure is summarized in Table 5.1.

Note that it may be unrealistic to assume that the interest rate on the debt in financing package 3 will be the same as the interest rate for financing package 2 because there is more credit risk in financing package 3. However, for purposes of illustrating the effects of leverage, let's keep the interest rate unchanged for now. We shall revisit this assumption later in the chapter.

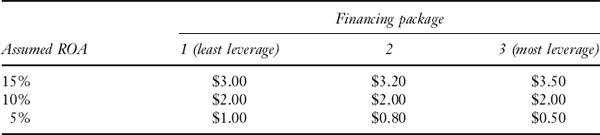

Suppose the firm has $4.5 million of operating earnings. We refer to the return that the firm earns on its operating assets as the return on assets (ROA). For our hypothetical firm, the ROA is 15% (=$4.5/$30). And suppose there are no taxes. To illustrate the concept of financial leverage, consider the effect of this financial leverage on the company's earnings per share. The earnings per share (EPS) is the ratio of the earnings available to the owners divided by the number of shares outstanding. The EPS for the three financial packages are shown in Table 5.2 assuming a 15% ROA.

Similarly, different EPS can be computed for different assumptions about the ROA. Table 5.3 shows the EPS for each of the three financing packages based on three assumptions about the ROA—15%, 10%, and 5%:

Notice that if the ROA is the same as the cost of debt, 10% in our illustration, the EPS is not affected by the choice of financing, because in that case the EPS is $2.00 regardless of the financing package. If the ROA is 15%, greater than the cost of debt, financing package 3 (with the greatest financial leverage) has the highest EPS. In stark contrast, if the ROA is 5%, less than the cost of debt, financing package 3 has the lowest EPS while financing package 1 with the least amount of financial leverage has the highest EPS.

TABLE 5.1 SUMMARY OF THE CAPITAL STRUCTURE FOR THREE FINANCING PACKAGES

TABLE 5.2 EARNINGS PER SHARE RESULTING FROM THREE FINANCING PACKAGES

TABLE 5.3 EARNINGS PER SHARE FOR DIFFERENT RETURN ON ASSETS FOR THREE FINANCING PACKAGES

This example illustrates the effect of debt financing on operating risk (as measured by the variability of operating earnings): The greater the use of debt vis-à-vis equity, the greater the operating risk. Additionally, by comparing the outcomes for the different operating earnings scenarios—$4.5, $3.0, and $1.5 million—the effect of adding financial risk to the operating risk magnifies the risk to the owners. Comparing the results, each of the alternative financing packages shows that as more debt is used in the capital structure, the greater the variability4 of the EPS.

When debt is used instead of equity (financing package 3), the owners do not share earnings over and above the contractual interest on the debt. But when equity financing is used instead (financing package 1), the original owners must share the increased earnings with the holders of newly issued shares, diluting their return on equity and EPS.

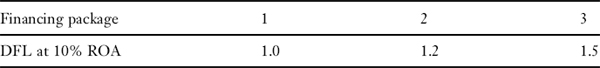

Another way to view financing effects is to calculate the degree of financial leverage, DFL:

![]()

The DFL for the three financing packages at a 10% ROA, or $3 million in operating earnings, is:

From the above, we can see that financing package 3 has the highest degree of financial leverage. Recall that increased leverage means more debt is used in the capital structure relative to equity, and consequently the greater the volatility of the EPS.

5.2.1 Financial Leverage and Financial Flexibility

The use of debt also reduces a company's financial flexibility. A company with unused debt capacity, sometimes referred to as financial slack,5 is more prepared to take advantage of investment opportunities in the future. The ability to exploit future strategic options is valuable and, hence, taking on debt decreases slack, with the result that the company may not be sufficiently nimble to act on valuable opportunities.

Empirical evidence provided by Booth and Cleary (2006) suggests that companies with more cash flow volatility tend to build up more financial slack and, hence, their investments are not as sensitive to the companies’ ability to generate cash flows internally. Rather, financial slack allows them to exploit investment opportunities quickly without the need to generate additional cash. Consequently, companies with highly volatile operating earnings may want to maintain some level of financial flexibility by keeping their debt financing relatively low.

5.2.2 Governance Value of Debt Financing

The free cash flow of a company is, basically, its gross cash flow less any capital expenditures and dividends. One management problem is how effectively a company uses its free cash flows. Jensen (1986) argues that by using debt financing, a firm reduces its free cash flows and, hence, the firm must reenter the debt market to raise new capital. Jensen theory, known as Jensen's free cash flow theory, contends that the need to issue debt benefits the firm in two ways.

First, there are fewer resources under control of management and less chance of wasting these resources in unprofitable investments. Second, being continually dependent on the debt market to raise new capital imposes a governance discipline on management that would not have been there otherwise. That is, a company's use of debt financing may help to reduce agency costs. Agency costs, discussed further in the next chapter, are the costs that arise from the separation of the management and the ownership of a company. They include all costs of resolving agency problems between management and shareholders, and also include the cost of monitoring company management. Agency costs further include costs associated with operating and informing a board of directors, as well as with providing financial information to shareholders and other investors.

5.3 CAPITAL STRUCTURE AND TAXES

We've seen how the use of debt financing increases the risk to the firm's shareholders: The greater the use of debt financing (relative to equity financing), the greater the financial risk. Another factor to consider is the role of taxes. In the United States, income taxes play an important role in a company's capital structure decision because, as mentioned above, a firm's payments to its creditors and its owners are taxed differently. In general, interest payments on debt obligations are deductible for tax purposes, whereas dividends paid to shareholders are not deductible. Because taxes affect the cost of financing, tax law naturally affects capital structure decisions.

5.3.1 Interest Deductibility and Capital Structure

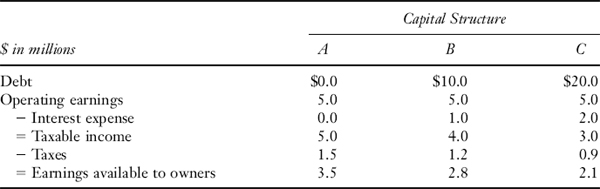

The deductibility of interest represents a government subsidy of debt financing: By allowing interest to be deducted from taxable income, the government is sharing the cost of a debt issue with the borrowing company. To see how this subsidy works, let's compare three capital structures for a firm that is assumed to have operating earnings of $5 million and the total assets of $35 million. The debt requires an annual payment of 10% and the tax rate is 30%. The three capital structures and the earnings available to the owners are shown in Table 5.4.

By financing its activities with debt, paying interest of $1 million, capital structure B reduces the company's tax bill by $0.3 million. The firm's creditors receive $1 million of the earnings, the government receives $1.2 million of the earnings, and the owners receive the balance of $2.8 million. The $0.3 million represents money the firm would not have to pay because it is allowed to deduct the $1 million of interest expense. This reduction in the tax bill is a type of subsidy. With capital structure C, the interest expense is $2 million and earnings available to owners are $2.1 million. Comparing capital structure C to A, we see that the interest expense is more, taxes are less, and earnings available to owners are less.

Consider the distribution of income between creditors and owners. The total income to the suppliers of capital increases from the use of debt. For example, the difference in the total income paid to creditors and equity owners under capital structure B compared to capital structure A is $0.3 million. This difference is due to a tax subsidy by the government: By deducting $2 million in interest expense, the firm benefits by reducing taxable income by $1 million and reducing taxes by $2 million × 30% = $0.3 million.

If we assume that there are no direct or indirect costs to financial distress, the firm's cost of capital should be the same, no matter the method of financing. It usually makes no difference to the firm's credit standing, and consequently to its creditors, whether the government does or does not subsidize the firm's owners. It is those owners who benefit from the tax deductibility of interest. We can see this by computing the return on equity (ROE)—the ratio of earnings available to owners divided by equity. Under capital structure A, the owners would have an ROE of 10% (= $3.5 million/$35 million). Compare this to the ROE under capital structure B, which is 11.2% ($2.8 million/$25 million) and 14% (= $2.1 million/$15 million) under capital structure C. For the two levered capital structures, the owners benefit from the tax deductibility of interest in that ROE increases.

TABLE 5.4 THREE CAPITAL STRUCTURES AND THEIR IMPACT ON EARNINGS

5.3.2 Interest Tax Shield

The benefit from tax deductibility of interest expenses is referred to as the interest tax shield, so named because it shields operating earnings from taxation. The tax shield from interest deductibility is:

Tax shield = Tax rate × Interest expense

Recognizing that the interest expense is the interest rate on the debt, which we will denote by rd, multiplied by the par value of debt, denoted by D, the tax shield for a company with a tax rate of τ is:

Tax shield = τ × rd × D

This tax shield affects the value of the company by reducing the firm's operating earnings that would otherwise go to pay taxes. The tax rate τ here refers to the marginal tax rate— the tax rate on the next dollar of income.

Of course, the value of the tax shield depends on whether the company can use an interest expense deduction. In general, if a company has deductions that exceed operating earnings, the result is a net operating loss. The company does not have to pay taxes in the year of the loss and may “carry” this loss to previous tax years, where (with some limits) it may be applied against those years’ taxable incomes.6 If the previous years’ taxable incomes are insufficient to absorb the entire loss, any remaining portion can (again with some limits) be carried over into future years, reducing future years’ taxable incomes. In such cases, the tax shield must be discounted at a rate that reflects both the uncertainty of realizing its benefit and the time value of money. Thus, the benefit from interest deductibility of debt depends on whether or not the company can utilize the interest deduction, and if so when.

5.4 THE COST OF CAPITAL

The capital structure of a company both affects and is affected by the company's cost of capital. The cost of capital is the return that must be provided for the use of investors’ funds. In raising new funds, the relevant cost of capital is a marginal concept. That is, the cost of capital is the cost associated with raising one more dollar of capital. If the funds are borrowed, the cost is the interest that must be paid to the holder of the debt instrument (a loan or bond). If the funds are equity, the cost is the return that investors expect to obtain, whether from stock price appreciation, dividends, or both.

In addition to affecting capital structure decisions, there are two other important roles played by a corporation's cost of capital. First, the cost of capital is often used as a starting point (a benchmark) for determining the cost of capital for a specific capital project in which management contemplates investing. Since many of a firm's projects present risks similar to the business risk of the firm as a whole, the firm's cost of capital may be a reasonable approximation for the cost of capital of a project with roughly similar business risk. However, if a project's risk differs from the firm's business risk, the project's cost of capital should be adjusted upward or downward, depending on whether the project's risk is more than or less than the firm's typical project.

A firm's cost of capital is the cost of its long-term sources of funds: debt, common stock, and such other forms of financing as preferred stock. The cost reflects the risk of the assets in which the firm invests. A firm that invests in assets having little risk will usually have lower costs of capital than a firm that invests in assets having a higher risk. Moreover, the cost of each source of funds reflects the hierarchy of the financial risk associated with its seniority over the other sources. For a given firm, the cost of funds raised through debt is normally less than the cost of funds from preferred stock,7 which, in turn, is less than the cost of funds from common stock. This is because creditors have seniority over preferred shareholders, who have seniority over common shareholders. If there are difficulties in meeting obligations, the creditors receive their promised interest and principal before the preferred shareholders, who, in turn, receive their promised dividends before the common shareholders.

Estimating the cost of capital requires management to estimate the cost of each source of capital along with the amounts raised from each source. Putting together all these pieces, the firm can then estimate the marginal cost of raising additional capital in the following three steps. In the first step, the proportion of each source of capital to be used in the calculations is determined. This should be based on the capital structure selected by the firm.

The cost of each financing source is calculated in the second step. The cost of debt and preferred stock is fairly simple to obtain, but the cost of equity is by far much more difficult to estimate. Several models are available for estimating the cost of equity, as described in later chapters. What is critical to understand is that these different models can generate significantly different estimates for the cost of common stock and, as a result, the estimated cost of capital can be highly sensitive to the model selected. The proportions of each source must also be determined before calculating the cost of each source since the proportions may further affect the costs of the sources of capital.

The last step is to weight the cost of each source of funding by the proportion of that source in the target capital structure.

For example, suppose the firm's capital structure as selected by management is as follows: 40% debt, 10% preferred stock, and 50% common stock. Assume further that management estimates the costs for raising an additional dollar of debt, preferred stock, and common equity are 5%, 6%, and 12%, respectively. If the company's marginal tax rate is 40%, the after-tax cost of debt is 5% × (1 − 0.4) = 3%. Returning to the illustration, the average cost of raising funds, referred to in this context as the weighted average cost of capital, is:

(40% × 3%) + (10% × 6%) + (50% × 12%) = 7.8%

This means that for every $1 the firm plans to obtain from financing, the cost is 7.8%. As management adjusts the firm's capital structure, the cost of capital for the firm would be expected to change. How the conditions under which the cost of capital changes when financial leverage is increased will be discussed in the next section as well as in Part VII of this book.

5.5 CAPITAL STRUCTURE IN A PERFECT CAPITAL MARKET: THE IRRELEVANCE THEORY

In this section we demonstrate that in an idealized financial environment, capital structure does not affect the firm's market value, a result that has come to be known as the Modigliani-Miller theorem.8 Since the theorem logically depends on the assumptions it employs, properly interpreting and using its findings in more complex circumstances requires further investigation, as we show in this section.

The Modigliani-Miller theorem assumes a perfect capital market under conditions of risk. In such a market, the following is assumed to hold:

- Buyers and sellers are all assumed to use the same probability distributions to characterize future uncertain returns (i.e., investor expectations are homogeneous). Financing decisions are further assumed to have no effect on the business risk of the firm.

- Buyers and sellers of securities cannot individually affect ruling market interest rates.

- There is no tax advantage associated with debt financing relative to equity financing.

- There are no costs associated with voluntary liquidation or bankruptcy, where bankruptcy is defined as a state when the value of the firm's debt exceeds the value of the firm's total assets.

- Although financial instruments must yield market returns commensurate with their risks, no transactions charges are paid on their purchase or sale.

- Any financial arrangements available to firms are assumed to be available to individuals on the same terms.

- Financial transactions capable of adversely affecting the positions of creditors relative to owners are not permitted, thus preventing involuntary expropriation of particular investors’ wealth positions.

5.5.1 Me-First Rules

The last assumption above means that debt holders protect themselves by including protective covenants, conditions that Fama and Miller (1972, p. 169ff) term me-first rules. In the context now being studied it is assumed that me-first rules can be enforced without costs. We illustrate the rules’ importance using several examples.

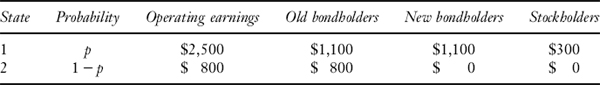

Consider first the case where a firm has some risky debt outstanding and also elects to raise additional debt at time 1. Both the outstanding debt and the new issue take the form of a bond. The existing bondholders are referred to as original bondholders, purchasers of the new issue as new bondholders. We assume the original bond has a par value of $1,000 requiring a 10% annual interest payment, and further that the new bond is issued on the same terms. Both bonds are assumed to mature at time 2, when each requires a payment of $1,100 (par value of $1,000 plus interest of $100). Moreover, it is assumed that the two bond issues have equal claims on the firm's assets in the event of bankruptcy: The two classes of creditors (i.e., bondholders) are said to be paid pari passu.

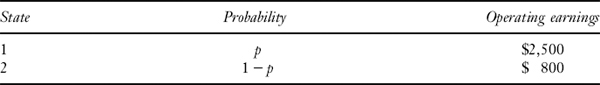

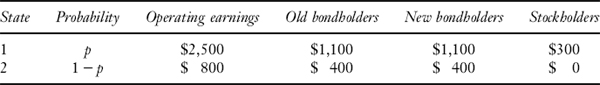

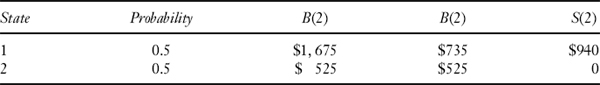

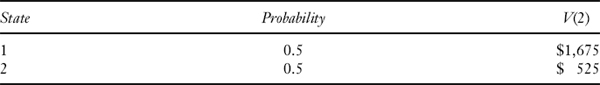

Suppose that the operating earnings of the firm are realized at time 2, that only two possible states of the world can occur, and that distribution of the two outcomes is:

Consider first the claim of the original bondholders if there was no additional bond financing. In state 1, the firm will have sufficient operating earnings to satisfy the claim of the original bondholders (i.e., $1,100). However, in state 2, the firm can only distribute $800 and by the terms of their contract, the original bondholders have a claim on that entire amount. Thus, the distribution of the claim of the original bondholders and the stockholders given the operating earnings is:

When a scheduled bond payment cannot be fully met from the operating earnings, the firm is technically insolvent. For purposes of the examples in this chapter, we suppose that under insolvency the bondholders receive whatever the firm is worth (i.e., all of the operating earnings), and no additional costs are incurred in liquidating the firm.

Now consider the claim of all the bondholders if new bonds are issued. In state 1 the firm has sufficient operating earnings to satisfy the claim of both bondholders ($2,200). However, in state 2 the operating earnings are only $800—not a sufficient amount to pay either class of bondholder. But the original and new bondholders are usually both paid based on the percentage of the par value of their claims. Since we are assuming that the obligation to either class of bondholders is $1,100, the $800 is distributed equally, $400 to each class. Thus, the distribution of the claims to the original and new bondholders is:

Comparing the distribution of claims of the original bondholders with and without the issuance of the new bonds, we see that this financing arrangement effectively expropriates a part of the wealth position of the original bondholders. At the same time, the financing arrangement does not change the distribution of funds available to the stockholders.

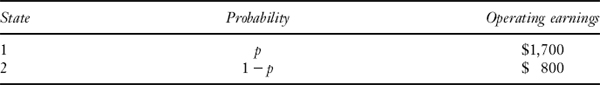

To prevent such an adverse occurrence for the original bondholders, the appropriate me-first rule in this case requires subsequent debt issues to be subordinated to the first (original) bondholder so as to leave the claim distribution of the original bondholders unchanged. Subordination of the new bondholders’ claim means that in state 2, the original bondholders have the first claim against the $800 operating earnings and, as a result, the new bondholders receive nothing. With these terms affecting the new bondholders, the claim distribution for all the suppliers of capital is:

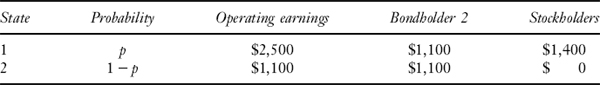

Stockholders also have rules that prohibit the firm changing its capital structure in ways that would affect them adversely. To see the me-first rule in this case, suppose that the operating earnings in time 2 remain the same as in our previous illustration for state 1 ($2,500) but that in state 2 they are $1,100 instead of the previous $800. Now we will assume that there are two bond issues outstanding, which we will refer to as bond issue 1 and bond issue 2. We will assume that the face value and interest on both bond issues is $1,000 and $100, respectively, and that the bonds are repaid pari passu at time 2. The distribution of claims for the bondholders and the stockholders is then:

However, suppose that bond issue 1 is retired by management at time 1. Then, unless other conditions were imposed, the claims for the holders of bond issue 2 and the stockholders would become:

In this event, the remaining bondholders would certainly be better off, and would become so at the expense of the stockholders. The remedy is to arrange that the stockholders receive compensation for leaving the bondholder in this better position. This effect can be brought about either by retiring all the bonds at the outset or by regarding the claims represented by the retired bonds as the property of the stockholders.

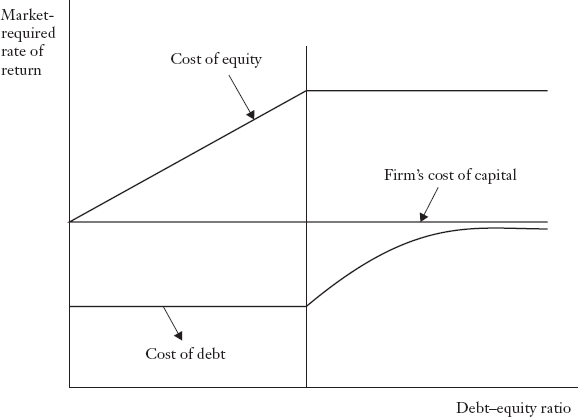

When me-first rules ensure that uncompensated shifts in wealth positions are ruled out, and when the capital market is also perfect in all other respects, the Modigliani-Miller theorem establishes that changes in capital structure do not affect the market value of the firm, and are consequently a matter of indifference to the individual classes of investors in the firm. Put another way, in a perfect capital market with no corporate taxation, the cost of capital to the firm (the market's required rate of return) remains constant as the debt-equity ratio changes.

5.5.2 Consequences of the Modigliani-Miller Theorem

The Modigliani-Miller theorem says stockholders’ wealth cannot be affected by changes in the firm's capital structure because the capital structure changes envisioned are prevented from affecting redistributions of the wealth positions to which individual investor classes lay claim. Rather, changes in capital structure merely repackage the earnings stream that determines the firm's market value. As long as the repackaging does not itself create additional costs or benefits, it cannot affect the firm's market value.10

One way of explaining that the market value of the firm is unaffected by capital structure changes in a perfect capital market is to show that under the foregoing assumptions any claims represented by financial instruments can be undone by investors. Recall that one of the assumptions of the previous section is that any financial arrangement available to firms is also available to individuals on the same terms. To understand the importance of this assumption, let's use another example. Suppose a firm, with a value of $1,500 at time 1, has a capital structure consisting of $1,000 in par value of bonds and $500 in equity. We'll refer to this capital structure of the firm as the “levered structure.” Suppose the bonds bear interest at a 12% interest rate11 and at time 2 the distribution of operating earnings is as follows:

Then the time 2 distributions of values to which bondholders and stockholders are entitled are as follows:

Now let's consider an alternative capital structure, to be called the “equity structure” because the firm issues only equity. To simplify the illustration, assume that one individual purchases all the equity, and hence is entitled to receive the entire operating earnings at time 2, earnings that have the distribution shown above. The time 1 market value of the equity remains at $1,500, since under present assumptions different capital structures do not affect firm value.

For the stockholder to create the same distribution as in the levered structure, the individual can issue bonds as a claim upon himself. Moreover, it is assumed that this can be done on the same terms as the firm so that $1,000 of par value bonds can be issued with a 12% interest rate. This possibility is referred to as “homemade leverage.” After the stockholder issues the bonds (which we also assume are bought by the same investors as those who purchase the firm's bonds), the positions of both the bondholders and the stockholder are the same as in the levered structure. Because it is assumed that investors can, on their own, costlessly reverse or otherwise alter the effects of capital structure decisions made by management, the market value of the firm is determined only by operating earnings and not by how management elects to divide up that distribution using varying combinations of debt and equity.12

5.5.3 Business and Financial Risk

Recall that the current discussion assumes operating decisions are given, implying that the business risk of the firm is not permitted to change. Nevertheless, as different financial claims are used by management to obtain funding, the financial risks associated with each class of claims can and usually do change, as illustrated next.

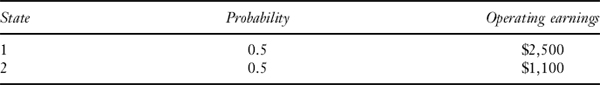

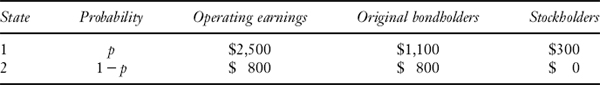

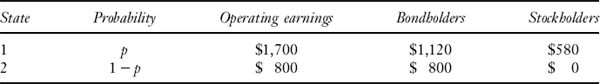

Suppose first that a firm that is financed only by equity and has the following distribution of time 2 operating earnings:

The expected value for the time 2 operating earnings, denoted by E[V(2)], is $1,800, and the standard deviation, denoted by σ[V(2)], is $700. Since the firm is 100% equity financed, the stockholders’ claims at time 2 have the same distribution, expected value, and standard deviation. The ratio of expected value to standard deviation can be interpreted as a measure of a claim holders’ financial risk. The lower this ratio, the greater the financial risk. For this 100% equity-financed firm, the measure is 2.6 (= $1,800/$700).

Now let's change the example. Suppose that at time 1 bonds promising to pay $1,000 (par value plus interest) at time 2 are issued, while the remaining financing of the firm takes the form of equity. Then the distribution of bondholder and stockholder claims is:

Based on the distribution for operating earnings above, the bonds can be seen to be riskless, since the claim of bondholders at time 2 is less than the lowest realizable value of the operating earnings available for distribution. That is, regardless of which of the two states occur, the bondholders will be paid in full. Since the expected value for the stockholders with the issuance of the riskless debt is then $800 and the standard deviation is $700, the ratio of expected value to standard deviation is 1.1 (= $800/$700), suggesting that the risk of the stockholders’ earnings stream has been increased by the issuance of riskless debt.

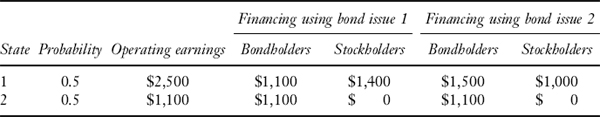

Now suppose that management is considering bond financing alternatives of either $1,100 or $1,500. We will refer to these alternatives as bond issue 1 and bond issue 2, respectively. Based on these assumptions, the distribution of payments to original bondholders, the new bondholders for the two alternative financing arrangements, and for the corresponding claims for the stockholders is as follows:

By comparing these two bond financing alternatives with our first example, we see that there is an upper limit of $1,100 to the promises that can be made using a riskless bond. If bonds promising greater repayments are issued, their payoffs become risky. At the same time, as the amount promised to bondholders increases beyond $1,100, the nature of the risk faced by the equity holders is no longer altered.13

FIGURE 5.1 COST OF CAPITAL UNAFFECTED BY LEVERAGE

The situation we have described is illustrated in Figure 5.1, which shows that, if enough bonds are issued, they eventually become risky. Nevertheless, whether the bonds become risky or not, our previous analysis shows that the market required rate of return on the firm as a whole (i.e., its cost of capital) remains unchanged as long as the conditions of the Modigliani-Miller theorem are satisfied. To see this in still another way, consider how the firm's cost of capital behaves as shown next.

5.5.4 Cost of Capital in a Perfect Capital Market

Since in a perfect capital market the firm's weighted average cost of capital depends only on the firm's business risk, the cost of capital does not change as the capital structure is altered. But the individual costs of the firm's debt and of its equity capital will depend on capital structure choices because they are affected by financial risks.

To see how this all works, let E(rj) be the cost of capital for firm j defined as follows:

where Vj(2) is the distribution of firm j values at time 2 and Vj(1) its market value at time 1. Similarly, the market rate of discount applied to the firm's bonds is:

where Bj(2) is the bond principal and interest at time 2 and Bj(1) the market value of the bonds at time 1. Primarily for simplicity of exposition, in this discussion we shall assume that bonds are riskless.

The rate of return on the firm's equity is defined as:

where Vj(2) − Bj(2) represents earnings available to stockholders at time 2 and Sj (1) the time 1 market value of this distribution. We now rewrite equations (5.1) and (5.2), respectively, as:

![]()

and

Bj(1)(1 + rj, B) = Bj(2).

We then substitute into equation (5.3) to obtain:

Then, since Vj(1) = Bj(1) + Sj(1), we can simplify equation (5.4) to:

![]()

Eliminating Vj(1) then gives:

![]()

Note that the ratio Bj(1)/Sj(1) is the firm j's financial leverage ratio, and that it increases as additional bonds are issued.

The upshot of the discussion is that in equation (5.5) E (rj) remains constant, but E (rj, S) increases with leverage. In other words, equation (5.5) reiterates that, while the expected return on the firm is constant, the equity risk—and hence, the rate of return required on the equity—can change as more debt is issued. In fact, it's easy to see why: More riskless debt means that equity claims cannot become less risky—either equity risk increases or remains unchanged.14

We now consider an example indicating how equation (5.5) reflects the manner in which financial risks change as the firm becomes more highly levered. The example will also exhibit the effects associated with issuing risky bonds. Suppose a firm has V(1) = $1,000 and the following distribution for V(2):

Then E[V(2)] is equal to $1,100, and the cost of capital for firm j is:

E(rj)={E[V(2)] − V(1)}/V(1) = {$1,100−$1,000}/$1,000 = 0.10

Now suppose that the firm issues bonds promising to pay $525 at time 2. Since the bonds will be risk free, they can be sold at the risk-free rate of interest, which we will assume is rf = 0.05. Under these circumstances, the market value of the bonds at time 0 is B(1) = $500 (= $525/1.05). Then, since V(1) = B(1) + S(1), it follows that S(1) = $500 also. Finally,

![]()

so that the required rate of return on equity is 15%.

If, instead of using both bonds and stocks, the firm had been financed only with equity, the discount rate applying to it would be 10%, since in this capital structure the owners of the equity would be entitled to the entire distribution V(2).

Let us now consider another capital structure where the amount of debt outstanding is large enough for the debt to be risky. Suppose debt with a face amount of $700 and an interest rate of 5% is issued; the distribution for V(2) remains the same as before. For this capital structure, the distributions to which the two investor classes are entitled are:

S(2) is related to the distribution of returns to stockholders in the first example (the present S(2) is $940/$1,150 of the value available in State 1 according to the first distribution). In Chapter 14, we will introduce an asset pricing model called the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and we will see that it establishes rates of return independently of a distribution's absolute size. Based on the CAPM we reason that the rate of return on equity in the present example must be 15% as in the first capital structure. This means that:

![]()

so that S(1) is approximately $409. Hence, B(1) = $1,000 − $409 = $591.

To obtain the discount rate that should be applied to the debt, recall that according to the Modigliani-Miller theorem, the firm's weighted average cost of capital must remain a constant 10%. This allows us to write:

![]()

so that the discount rate applied to the bonds is now calculated to be 6.6%. We can check this by noting that:

![]()

Thus, we see that for the particular firm in question, debt is riskless until the debt-equity ratio reaches unity, after which point the debt becomes risky. The relations between discount rates applied to the firm and to the two classes of securities are shown in Figure 5.2.

Note that even though the cost of equity rises as the firm becomes more highly levered, we do not have (in the absence of the effects of tax differentials or costs for defaulting on the promised debt repayment) any statement to the effect that debt affects the firm's cost of capital. In fact, more debt does not lower the average cost of funds in the present example even though debt always has a lower required return than equity. On the other hand, large issues of debt do not raise the cost of capital either because (as we have assumed) defaulting on the debt involves no bankruptcy costs. In this case, risky debt is, apart from its priority of claim, treated just like equity; that is, it is treated as a risky proposition discounted at a rate reflecting its risk. The constant cost of capital result follows because the rate at which the firm's total income stream is capitalized (discounted) remains constant even though the capital structure is altered.

FIGURE 5.2 EFFECT OF LEVERAGE ON REQUIRED RETURNS ON STOCKS AND BONDS

The managerial implication of these findings is that we have not yet found any reason for management to be concerned with leverage (i.e., the capital structure appears to be irrelevant). However, Part VII will identify features of a firm's capital structure that do affect the firm's value.

KEY POINTS

- The capital structure decision is usually analyzed by managing the risks associated with financing decisions while taking a company's business risk as given.

- The cost of capital is the return that must be provided for the use of an investor's funds.

- An optimal capital structure is the mix of financing that maximizes the firm's value. If an optimal structure exists it will both maximize firm value and minimize the firm's cost of capital.

- The concept of financial leverage plays a role in affecting investor risk because leverage exaggerates the impacts of either favorable or unfavorable outcomes.

- Financial leverage makes use of additional debt; that is, increased leverage increases the firm's debt-equity ratio.

- Taxes provide an incentive to increase debt financing because interest paid on debt is a deductible expense for tax purposes, and thus, works to shield income from taxation.

- Since the capital structure of a company is intertwined with the company's cost of capital, estimating the latter is important for both capital structure decisions and capital budgeting decisions.

- The weighted average cost of capital is the estimate of a firm's cost of capital found by first computing the after-tax cost of each type of funding source and weighting each cost by the targeted percentage of the funding source sought by management.

- Although the cost of debt and preferred stock is relatively easy to determine for small amounts of new issues, the cost of equity must be estimated using some economic model.

- The Modigliani-Miller theorem asserts that in a perfect capital market, the capital structure decision does not affect the firm's market value; that is, the capital structure decision is irrelevant and therefore, there is no optimal capital structure.

- Under the assumptions of the Modigliani-Miller theorem, changes in capital structure merely repackage the earnings stream that determines the firm's market value. As long as the repackaging can occur without itself creating additional costs or benefits, it cannot affect the firm's market value.

- The main reason the market value of the firm is unaffected by capital structure changes in a perfect capital market is that the capital structures change the way an income pie is divided, but without affecting the size of the pie.

- An assumption in the Modigliani-Miller theorem is that financial transactions capable of affecting adversely the position of creditors vis-à-vis owners are not permitted; that is, involuntary expropriation of particular investors’ wealth positions is not allowed.

- Creditors can protect themselves against management taking action that would adversely impact their wealth position by including protective covenants, conditions referred to as me-first rules. It is assumed that creditors can enforce the me-first rules without cost.

- In a perfect capital market the firm's weighted average cost of capital depends only on the firm's business risk. Since altering the capital structure does not change business risk (even though it does change financial risk), the cost of capital does not change as the capital structure is altered.

- For the weighted average cost of capital to stay constant in a perfect capital market when more leverage is added, the cost of equity will rise to offset the effects of lower cost debt being added to the capital structure.

QUESTIONS

- What do the investors in a firm expect if a firm retains earnings rather than distributing earnings in the form of dividends?

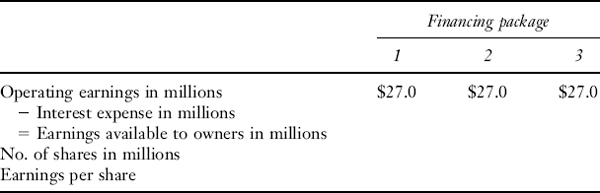

- Suppose that the Matrix Corporation has $120 million of assets, all financed with equity, and that the firm has 6 million shares of stock outstanding valued at $40 per share. Suppose further that management has identified investment opportunities requiring $60 million of new funds and can raise the funds in one of the following three ways:

Financing package 1: Issue $60 million equity (3,000,000 shares of stock at $40 per share) Financing package 2: Issue $30 million of equity (1,500,000 shares of stock at $40 per share) and borrow $30 million with an annual interest of 8% Financing package 3: Borrow $60 million with an annual interest of 8% - Complete the following table for each financing package after the financing capital structure is completed:

- Suppose the Matrix Corporation has $27 million of operating earnings. Show that the firm's return on assets is 15%.

- Assuming there are no taxes, compute the earnings per share for the three financing packages by completing the table below:

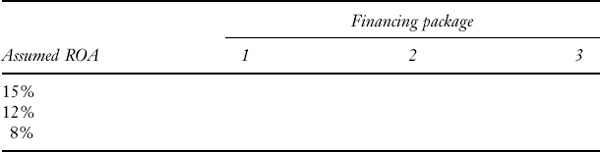

- Complete the table below for each of the three financing packages based on three assumptions for the return on assets shown below:

- Based on the calculation in part d, when is the choice of financing irrelevant?

- If operating risk is measured by the variability of operating earnings, what is the relationship between the use of debt relative to equity and the risk associated with operating earnings?

- Assuming that the return on assets is 8%, what is the degree of financial leverage for the three financing packages?

- In this problem, the interest rate on the debt in financing package 3 is assumed to be the same as the interest rate for financing package 2. Why might this assumption be unrealistic?

- Complete the following table for each financing package after the financing capital structure is completed:

- Why does the use of debt reduce a firm's financial flexibility?

- The following excerpt is from an article entitled “Valuing Financial Slack in the Steel Sector” by David Merkel in October 15, 2003 (RealMoney.com: http://www.thestreet.com/p/rmoney/davidmerkel/10119562.html)

“As far as investors go, I'm a singles hitter. It can be tough to find investments that more than double your money, but I aim for a pretty high batting average overall. One key to such success is insisting that the companies in which I invest possess financial slack.”

What does the author mean by financial slack?

- a. What is meant by free cash flow?

b. What are the two implications of Jensen's free cash flow theory for debt financing?

- What is meant by an interest tax shield?

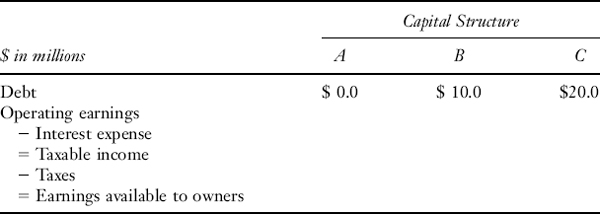

- XYZ has operating earnings of $40 million and total assets of $280 million. The company's management is considering three alternative capital structures. The debt requires an annual payment of 12% and the tax rate is 40%.

a. The three capital structures are given the table below. Compute the values in the table:

b. Explain how financing its activities using capital structure B reduces the company's tax liability.

c. Explain how financing its activities using capital structure C reduces the company's tax liability.

d. Based on the calculations above, explain how the total income to the suppliers of capital increases from the use of debt.

- a. What is meant by a company's cost of capital?

b. Why is the company's cost of capital critical in the financial decisions that management must make?

- Assume that a firm's capital structure consists of 30% debt and 70% equity. Further assume that the cost of debt and the cost of equity are 6% and 10%, respectively.

- What is the weighted average cost of capital if the firm pays no taxes?

- What is the weighted average cost of capital if the firm is in the 30% marginal tax rate?

- What is the weighted average cost of capital if the firm is in the 40% marginal tax rate?

- One of the assumptions of the Modigliani-Miller theory regarding capital structure is that debt holders protect themselves by including “me-first rules.”

- What is meant by me-first rules?

- Give an example of a me-first rule.

- According to the Modigliani-Miller theorem, what are the implications of changes in the firm's capital structure for stockholders’ wealth?

- a. What is meant by a firm's business risk?

b. According to the Modigliani-Miller theorem, the firm's weighted average cost of capital depends only on the firm's business risk and not its capital structure. Explain why.

REFERENCES

Booth, Laurence, and Sean Cleary. (2006). “Cash Flow Volatility, Financial Slack, and Investment Decisions,” Working Paper, University of Toronto (January).

Fama, Eugene F., and Merton H. Miller. (1972). The Theory of Finance. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Jensen, Michael C. (1986). “Agency Cost of Free Cash Flow, Corporate Finance, and Take-overs,” American Economic Review 76, 2: 323–329.

Modigliani, Franco, and Merton H. Miller. (1958). “The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance, and the Theory of Investment,” American Economic Review 48: 261–267.

1 More complex kinds of equity issues are discussed in Chapter 23.

2 In Chapter 10 we provide another interpretation of why the firm's capital structure is irrelevant in a perfect capital market without corporate taxation. The framework we use is contingent claims analysis, an especially convenient way of disentangling the meaning of capital structure change.

3 A value maximizing capital structure will depend on several factors that we discuss later in this chapter.

4 Variability is commonly called volatility, and sometimes the swing. It is usually measured by either the variance or the standard deviation of the measure in question, in this case the EPS.

5 It is not always easy to define financial slack: Its size is really determined by creditors and their attitudes towards the firm.

6 The previous years’ taxes are recalculated and a refund of taxes previously paid is requested.

7 Preferred stock is not available in all countries.

8 Modigliani and Miller (1958).

9 The probabilities referred to in this chapter are the underlying or objective probabilities of the states.

10 The theorem also implicitly assumes that markets are so constituted that decisions made by a firm's management cannot restrict investor opportunities. When these conditions are relaxed, the Modigliani-Miller predictions require modification. But since these matters are of greater concern to the welfare theory of financial markets than they are to corporate finance, we do not consider them further here.

11 Note that (1) the bonds are not riskless as interest and principal cannot be fully paid and (2), if technical insolvency caused by default on the bonds should occur, it does not lead to any extra costs.

12 That is to say, the focus is on the pie and not on how it is sliced. This is because no crumbs are lost if and when the pie is sliced. Indeed, the pie can also be unsliced without any loss of crumbs.

13 The precise quantitative results depend on our assumption of a probability distribution with only two possible outcomes (i.e., two possible states). In more complex cases, the effect on the equity as bonds become risky is one of increasing equity risk. However, the increase occurs at a decreasing rate as the debt-equity ratio increases.

14 As previous examples have shown, in some cases the equity risk can reach a maximum and then cannot increase further beyond that point, even as leverage is further incremented.