7

FINANCIAL SYSTEMS, GOVERNANCE, AND ORGANIZATION

In this chapter and the one to follow, we explain how financial systems are organized and why they assume those forms. This material is intended to provide a practical context for the financial transactions examined in the rest of the book. Even though financial systems may initially appear to be complicated entities, financial economics offers a straightforward analytical and descriptive picture of how such systems work. A financial system performs a set of tasks, called functions. One way to study financial systems1 involves examining the arrangements reached between financiers and their clients in a process called alignment. These alignments are studied principally in the context of financial deals that involve either commitments of financial resources (i.e., fund-raising), reallocation of risks2 (risk transfer), or both.

All financial systems perform similar functions, but differ in the relative importance of the three major forms of governance they use: (1) financial markets, (2) financial intermediaries, and (3) internal allocations. Governance is the process of suitably contracting a financial arrangement at the beginning and of tailoring the arrangement to ensure, as far as possible, its profitable conclusion. Some deals depend on continuing supervision to strengthen the possibility of their profitable conclusion. At any point in time, the attributes of financial deals, the organizations funding them, and the capabilities of the organizations’ governance methods jointly determine the financial system's organization.

Analyzing the workings of a financial system thus involves identifying (1) the major attributes of proposed financial deals; (2) the capabilities of the organizations (financial entities) that provide financing, risk transfer, or both; and (3) how the attributes of clients’ deals can be aligned with financial entities’ governance capabilities. Since the entities and their clients both strive to achieve cost-effective forms of funding, a financial system's static organization is determined principally by economic considerations. Although in practice not every type of financial deal is governed cost-effectively from the outset, governance choices typically evolve toward greater efficiency as economic agents learn. That is, both a system's static organization and its evolution are largely determined by a combination of learning and the changing economics of performing different financial functions.

In comparing financial systems, it becomes evident that each of the three major financing mechanisms complements the other two. Hence, explaining the allocation of financial resources necessarily involves examining these complementary roles. For example, in some economies financial markets are not very important, and most financial resources are allocated through financial intermediaries. In these economies, an analysis of financial markets would give a very incomplete picture of how the financial system works. As a second example, studying the financial intermediaries in a financial system does not show how intermediaries complement both market and internally provided forms of finance. Even for developed economies such as those of the United States and the United Kingdom, a comprehensive understanding of the financial system requires examining the complementary roles played by the principal types of external finance—market and intermediated transactions—as well as the complementarities between external and internal finance.

The study of financial systems is worthwhile both for its own sake and because financial activity contributes importantly to economic well-being. Yet these beneficial effects are rarely apparent to casual observers. Indeed, some readers of the financial press may have the misleading impression that a financial system is principally a set of markets in which shares of stocks and exotic instruments such as financial derivatives are traded. But in fact, financial activity generates a significant share of national income in many economies, and most of this income is generated by performing everyday functions, such as transferring funds between economic agents, investing accumulated wealth, funding viable new projects, and managing risks.

At the same time, a financial system's economic importance extends well beyond performing everyday functions. Macroeconomic theory explains that while consumption, investment, and government spending are the major determinants of economic activity over the near term, changes in the rate of investment (capital formation) importantly affect the rate of economic growth. Moreover, different amounts and types of capital formation can also affect an economy's productivity and its international competitiveness. A financial system plays an important role in determining these effects, since capital formation is affected by conditions for obtaining financing.

In this chapter, we begin with a functional approach of the permanent features of financial systems and then examine financial activity at the level of individual deals. After outlining the concepts of deal attributes and financing capabilities, the chapter contends that agents strive to negotiate cost-effective alignments and that financial structure represents groupings of these alignment activities. We then turn to financial system governance, the types of governance, and the mechanisms for governance of financial systems. In Web-Appendix A, we provide a description of how the terms of a financial deal can perfect the capabilities utilized in its governance.

7.1 FINANCIAL SYSTEM FUNCTIONS

The unchanging functions3 performed by every financial system include:

- Clearing and settling payments

- Pooling resources

- Transferring resources

- Managing risks

- Producing information

- Managing incentives

Although every financial system performs these functions, the organizations carrying them out are determined endogenously in response to the characteristics of the local economic environment and currently available transactions technology. Thus, the observed structures of financial systems can differ, both at any point in time and also over time.

In this section, we examine these six functions that comprise relatively permanent features of financial systems. Identifying the unchanging features of financial activity is a useful exercise for two reasons. First, when the present discussion of relatively permanent functions is combined with the analysis of financial deals and their governance later in this chapter, we will be able to describe financial activity comprehensively, using differing combinations of a few basic financial deal attributes and a few basic governance capabilities. Second, identifying these basic dimensions helps understand how financial system organization emerges endogenously from the economics of governing deals, as well as indicating how it is likely to evolve in the future.

7.1.1 Clearing and Settling Payments

One principal financial function involves clearing and settling payments, both domestically and internationally. In essence, clearing and settling payments mean that a payment order requiring one agent to pay another is executed by a third party who effects a transfer of funds from the payer's to the payee's institution. Although settlement has been a traditional financial system function throughout history, today funds are mainly transferred electronically, and payments are made much more quickly than they were even as recently as in the 1980s. The financial system now makes it easy and cheap to transfer funds quickly between almost any two points in the world, and usually in whatever currency the payer desires to use. The increasing use of credit cards, debit cards, and cards that function as electronic purses all contribute to an important form of change in the retail payments system.

7.1.2 Pooling Resources

Resource pooling is a second financial system function. Some of the ways in which savings are pooled at the retail level are through bank deposits, mutual funds, other stock investments, and insurance policies. While savers are concerned with the expected return on their funds, most also want to ensure their wealth is invested relatively safely. A well-developed financial system acts to store wealth, not without any risk, but at a risk commensurate with the expected rate of return on the investment. Since investors are usually risk-averse, they normally demand that asset returns increase as the perceived risk of an investment increases. As is well confirmed by empirical research, informed savers profit from one of the most important conclusions of modern financial theory: The expected return on an asset normally increases with the systematic risk the asset bears.

Funds are also pooled at the wholesale and commercial level. The most well-known instruments of this type are securities issued to raise funds for pooled forms of debt that were originally granted by banks and other lenders through a wide range of what are called asset-backed securities. Institutions like insurance companies, pension funds, and hedge funds are willing to invest in asset-backed securities because they are in effect lending against portfolios of loans rather than against individual loans. The securities are likely to be safer than the individual loans in the pool, because the securities have the entire diversified loan pool as collateral.4

7.1.3 Transferring Resources

A third basic function is to transfer resources, not only from one geographical region to another, but more importantly from one time period to another. Resource transfers through time in effect channel funds from savers to borrowers, thereby facilitating lending or investing. The funds used to finance new investment by businesses are typically raised from both domestic and foreign sources. Through financing new productive activity, the financial system stimulates economic growth.

7.1.4 Managing Risks

Managing risks, a fourth basic financial system function, includes everything from retail transactions such as selling car insurance to wholesale transactions and trading derivative instruments in international markets. Indeed, almost every aspect of economic life is subject to various forms of either risk or uncertainty. Kenneth Arrow (1974), the corecipient of the 1972 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science, notes that pooling, sharing, and shifting risks are pervasive forms of economic activity. The ability of an individual or business enterprise to shift risks of losses from fire or theft to specialized insurance companies provides an obvious example of a retail transaction. The stock and derivatives markets can all be seen as providing certain forms of wholesale risk management.

Historically, a series of institutions and arrangements have evolved to carry out risk management activities, and the arrangements continue to evolve. The concept of risk management has been familiar to providers of funds for a long time. For example, insuring some of the risks of trade was practiced by caravans following the silk routes. From such historical beginnings, insurance companies were formed principally to assume risks that others were unwilling to bear. Other risk instruments such as commodities futures have also been traded actively for a long time.

As the discussion suggests, risk trading is a kind of insurance activity. It is not particularly fruitful to regard it as a form of gambling in which financiers make money at the expense of uninformed players. Indeed, the growth of risk trading represents a valuable economic function aimed at spreading rather than at increasing risk.5 Probably most people would agree that buying fire insurance can be a good idea, but fewer observers realize that such forms of financial engineering as using derivative instruments to hedge portfolio risk are conceptually similar. Buying fire insurance is a familiar transaction, but hedging portfolio risk seems exotic and strange until one gets to know it better.

7.1.5 Information Production

The fifth basic function of a financial system is information production. As pointed out earlier, well-functioning markets foster information production. The efficient markets hypothesis holds that, when markets are perfectly competitive and trading is not impeded by transactions costs or institutional practices, securities will have equilibrium prices that fully reflect all publicly available information. The differences between instruments traded in efficient markets are captured in their risk-return characteristics.

Exchange trading in derivatives offers a second example of information production, and many derivatives markets are also efficient information producers. Derivatives trading was not originally thought of as an information-producing activity, but option pricing theory6 has made it evident that the prices of traded options can be used to obtain estimates of underlying asset volatilities. Volatility information can be used to interpret the degree of earnings uncertainty a given asset presents, and this information can prove valuable for making investment decisions.

Financial intermediaries also perform information production roles, but the information produced by these entities is not usually disseminated publicly. For example, financial intermediaries develop information when they evaluate loan applications, but this information is normally used privately by the intermediaries to decide whether or not credit will be extended to given clients. Nevertheless, skillful production of this information is also essential to economic well-being—without it institutions would be less discriminating in their lending and investment activities, and fewer good projects would be able to obtain funding.

7.1.6 Managing Incentives

Still another form of financial system function involves managing incentives, especially incentives arising from informational differences. Informational differences can create situations in which, say, a client has private information that can put the financier at a disadvantage. Managing the potential difficulties presented by informational differences is the essence of everyday financial activity. For example, credit departments of banks investigate borrowers before loans are made, and subsequently monitor the activities of the borrowers to ensure that the terms of the contract are observed. Insurance companies investigate risks before they underwrite them. They also limit the kinds of activities or assets they will underwrite, thus affecting the incentives of the insured.

Incentive considerations affect both lender and borrower. A borrower providing information to a potential lender risks giving away a knowledge advantage. Both the borrower and the lender need protection against exploitation by the other, and in recognition of this possibility, some financiers try to develop reputations for helping rather than exploiting borrowers.

7.2 FINANCIAL SYSTEM GOVERNANCE

All financial transactions require governance. By financial governance we mean the process of looking after financial transactions with a view to suitably contracting the arrangement at the beginning and with a further view to ensuring, as far as possible, its profitable conclusion. Although all financial transactions require governance, in this chapter and the next we focus on two main types: (1) transactions aimed primarily at raising funds and (2) those aimed primarily at managing risks. Both types are what we refer to generically as financial deals.7

Governance capabilities are particularly important for securing the expected profits from financial deals. If funds are being raised, financiers commit resources over time and must subsequently recover the funds invested, with compensation for the expected risk involved, if the financiers are to prosper. Similarly, financiers entering risk management deals must price and govern the risks appropriately. Financial deals that are well governed can be expected on average to reward financiers for assuming risks, while ineffectively governed financial deals have substantially greater probabilities of making losses.

The mechanisms for governing financial deals are variations of financial market, financial intermediary, and internal funding arrangements. Cost-effective alignments of financial deals with the most suitable types of mechanisms depend on both deals’ attributes and financiers’ governance capabilities. While each alignment of a financial deal and a mechanism is likely to have some distinctive features, financial system analysis is simplified by recognizing that deals can be grouped according to their combinations of attributes, and the economics of governance usually leads financiers to select a particular mix of capabilities for the deals’ governance.

7.2.1 Types of Financial Governance

In the previous section, we discussed the main functions carried out by the financial system. This section offers a complementary analysis that begins at the level of the individual transaction, referred to as the financial deal. Once the processes of agreeing and governing individual transactions have been examined, we then consider how financiers aggregate financial deals, and how the aggregations of deal types endogenously determine the kinds of institutions and markets present in a financial system.

Financial governance can be regarded as utilizing a few capabilities drawn from a fixed taxonomy, and financial deals can be described in terms of a few critical attributes, drawn from a second fixed taxonomy. Financiers with given capabilities usually accept financial deals with particular attribute combinations. In addition, financial firms choose a form of business organization that is intended to facilitate cost-effective governance. At the aggregate level, financiers’ organizational choices are determined endogenously by the attributes of available details and the economies of governing those attributes. Alignment of attributes and governance capabilities results in the structure of a financial system. That is, the combination of financial markets, financial intermediaries, and internal governance that a financial system represents is also determined endogenously by the economics of governance and the operating economics of the organizations implementing the governance methods.

External finance is provided by both financial markets and financial intermediaries, and clients’ choices among alternative financing forms depend on both the cost and the perceived stringency of the financing conditions. Differences in financing terms stem from differences in market structure, from differences in borrower and lender information, and from the incentives the informational conditions create. In particular, informational differences between financiers and their clients can create problems that increase the costs of any financial deals that are actually agreed upon. If the problems caused by informational differences are severe enough, external finance may not be obtainable even at a very high cost.8 Even in an economy with a highly developed financial system, a considerable proportion of business financing is provided internally from business’ own resources. Decisions to finance internally rather than externally will usually depend on the perceived risk or uncertainty inherent in the proposal, the cost of the external funding, and the perceived stringency of the funding conditions.

Some financial systems (those of the United States and the United Kingdom, for example) channel a relatively large proportion of external financing through financial markets, while others (those of France, Germany, and Japan, for example) channel a greater proportion through financial intermediaries. These differences in the relative importance of different financing sources are reflected in the terms market-based systems and intermediary-oriented systems. For example, it is customary to describe the financial systems of the United States and the United Kingdom as “market-oriented”; those of France, Germany, and Japan as “intermediary-based.” However, the differences between market-oriented and intermediary-oriented systems are to some extent a function of historical development, and as the global financial system continues to evolve, the search for efficient forms of financing continues to reduce the differences between the two classifications.

Markets and intermediaries utilize different capabilities, and are therefore not equally well suited to governing the same types of financial deals: in a static and efficiently organized financial system the types of financings arranged in markets will differ from the types arranged with intermediaries.9 Thus, at the system level, a strongly market-oriented system could exhibit different aggregate performance characteristics than a strongly intermediary-oriented system.

Market-oriented and intermediary-oriented financial systems develop public and private information in different proportions. Through trading, markets aggregate the impact of widely diverse forms of public information. Portfolios composed largely of securities that trade actively in financial markets have readily established values that are frequently described as transparent. On the other hand, intermediaries offer greater potential for in-depth, private development of credit information. Since intermediaries acquire relatively large proportions of nontradable assets, their portfolios have less easily established values that are often referred to as opaque.10

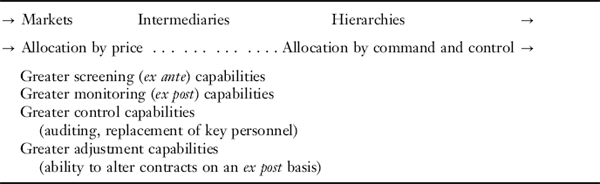

7.2.2 Governance Mechanisms

The three principal mechanisms for governing the allocation of financial resources are markets, intermediaries, and internal organizations. Internal organizations are also referred to as hierarchies. Each type of mechanism utilizes a mix of capabilities drawn from a fixed taxonomy. Here we will explore the differential capabilities of the three main mechanisms.11 Table 7.1 presents a schematic representation of the differences between governance mechanisms and their capabilities. As the table indicates, the type of allocation mechanism ranges along a continuum indicating that (1) markets typically allocate financial resources using the price mechanism, (2) intermediaries combine allocation by price with some forms of command and control, and (3) hierarchies such as financial conglomerates provide finance primarily using command and control mechanisms. The capabilities of the mechanisms increase in both effectiveness and cost along a continuum having market governance at one extreme, and internal governance at the other. The ideas underlying the table are examined in the following sections.

TABLE 7.1 MECHANISMS AND GOVERNANCE CAPABILITIES

7.2.2.1 Market Finance

Markets allocate financial resources by price, which in the context of a financial transaction refers to a financial deal's effective funding cost. Market governance works best when a financial deal's essential attributes can be captured by the funding cost it bears. Such financial deals’ essentials can be reflected by terms that are fully specified at the outset, meaning that financial deals consummated by market agents can usually be regarded as complete contracts. Most financial deals that market agents entertain require relatively little monitoring after being struck, often because market deals finance the acquisition of assets with a ready resale value in secondary markets.

Typically, market agents carry out trades between parties who do not necessarily know each other. Moreover, market agents often have well-developed research and information-processing capabilities regarding readily observable short-term changes in each financial deal's likely profitability. For example, market trading of a firm's shares determines the value of the firm's underlying assets. As a second example, trading derivatives prices volatility,12 and thereby produces economic information about how different risks are valued in the marketplace. As Allen and Gale (2000) observe, markets are especially well suited to assessing the economic impact of a variety of disparate forms of information.13

Market agents attempt to realize scale economies by standardizing the terms of the deals they take on, and thereby reducing the transactions costs of a financial deal. Market agents can also realize economies of scale if the same specialized information-processing techniques can be used for numbers of similar financial deals. The most active markets usually deal primarily in standardized contracts, a category that includes the public share issues of widely traded companies. On the other hand, less active markets deal principally in contracts that can be more varied in their terms.

Within the markets category, distinctions can be made on the basis of differences in the capabilities of market agents. For example, private markets, in which securities are sold to one or a small group of investors, typically permit more detailed ex ante screening and more detailed negotiation of a financial deal's terms than do public markets in which securities are sold to a relatively large number of investors on standard terms.

7.2.2.2 Intermediary Finance

Financial intermediaries are enterprises that raise funds from savers, mainly householders and to a lesser extent businesses. The major financial intermediaries are depository institutions such as banks whose funds are raised via deposits. These financial intermediaries relend the funds to business and personal borrowing customers, and in most developed economies, they provide the largest proportion of loan funds obtained by those ultimate users. The public normally views intermediary deposits as highly liquid, and expects to be able to withdraw the nominal amounts of their deposits on short notice. On the other hand, most of the loans granted by financial intermediaries are illiquid, typically being repaid in installments over months or years. Hence, financial intermediaries must manage a portfolio of relatively illiquid assets that are funded by relatively short-term liabilities.14

Loans granted by financial intermediaries specify an interest rate, and therefore, utilize a form of resource allocation by price, but the arrangements also incorporate a greater use of command and control mechanisms than is typically found in market transactions. As a result, intermediaries exercise certain kinds of governance capabilities that are not customarily utilized by market agents. The additional capabilities that financial intermediaries utilize include more intensive ex ante screening capabilities, more extensive capabilities for monitoring, control, and subsequent adjustment of financial deal terms. Intermediaries use these combinations of capabilities because they offer cost-effective ways of governing the financial deals they enter. Intermediaries produce private information by screening loan applications ex ante, aswell as by ex post monitoring of deals they have already entered. Information produced by financial intermediaries remains private because they do not normally trade their financial assets.15 The contracts drawn up for intermediated financial deals are incomplete in comparison to the contracts drawn up for market financial deals. In particular, they may have implicit terms that are not actively invoked unless the originally agreed financial deal appears to be in some danger of producing less revenue for the financier than was first contemplated.

Not all intermediaries can screen all types of financial deals equally well, and differential capabilities help to explain why intermediaries are likely to specialize, at least to a degree. For example, some intermediaries can offer automated screening of credit card and consumer loan applications, thereby enjoying scale economies not available to those with smaller volumes of the same business. As a second example, expert systems and credit scoring techniques are coming to play an increasingly important role in assessing many types of deals, including business lending. Such systems exhibit declining average costs, chiefly because they require a large initial investment, but have relatively small marginal operating costs. As a result, expert systems will most likely be installed by a relatively small number of large firms. If they can negotiate profitable terms, smaller firms may purchase the services from their larger counterparts.

7.2.2.3 Internal Governance

Internal governance, also referred to as hierarchical governance, represents financial resource allocation using command-and-control capabilities to a still greater extent than that used by financial intermediaries. Internal governance offers the greatest potential for intensive ex ante screening, ex post monitoring, control over operations, and adjustment of financial deal terms. Hierarchical mechanisms typically focus less on the nature of a financial contract and more on the command-and-control mechanisms they can use to effect ex post adjustment of financing terms. Internal governance is likely to be more expensive than market or intermediated governance, and as a result will normally be used to govern financial deals whose uncertainties are greater than those acceptable to intermediaries.

For example, internal capital market transactions may be the only feasible way of governing financial deals whose problems of incomplete contracting are relatively severe. Internal governance provides highly developed capabilities for auditing project performance, for changing operating management, and for adjusting financing terms if conditions change. On all these counts, internal financing arrangements employ different governance capabilities from those of either market agents or intermediaries, but also at higher administrative costs than those of the former two. Of course, in order to be viable such financial deals must offer a potential for both covering higher governance costs and for returning greater rewards.

7.2.3 Types of Financial Deals

Financiers are faced with proposals for what appear to be many different types of financial deals. Indeed, on the surface deals differ so much that it might seem necessary to describe each one separately. However, at a macro level, differences among financial deals can be described as different combinations of a few basic attributes.

7.2.3.1 Deal Attributes

Some deals are so familiar to financiers that their successful conclusion depends primarily on the results of an initial screening followed by using a standard form of governance. These simple forms of financings arise either when clients acquire relatively liquid16 assets, or when collateral with a readily established market value can be used for security. In either case, such kinds of financings are relatively easy to arrange because in the event of difficulty, the underlying asset values can be used to repay most or all of the funding. The simplest kinds of risk management financial deals are similarly standardized. Such financial deals present risks rather than uncertainties, can be formalized using rule-based, complete contracts, and are relatively easy to price. Accordingly, such financial deals can usually be agreed upon after only relatively cursory investigation.

Other financial deals may be unfamiliar to financiers, have unusual terms, and present greater uncertainty regarding the likelihood of repayment. These more complex kinds of financial deals often involve financing the purchase of illiquid assets when there is no collateral to serve as security in the event of a failure to satisfy the terms of the financial deal. For example, financial deals (i.e., investments) made by specialized entities known as venture capitalists whose success rests on the talent and commitment of given individuals are deals in which financiers’ rewards will depend on highly uncertain future earnings. There will usually be little in the way of marketable assets available to provide security.

TABLE 7.2 ATTRIBUTES AND GOVERNANCE IMPLICATIONS

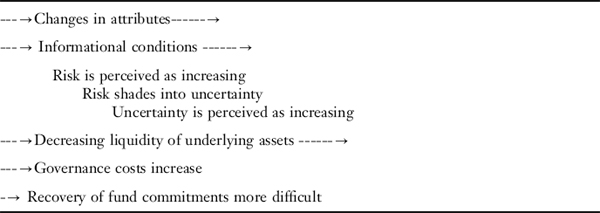

Table 7.2 indicates that increasing information differences, decreasing asset liquidity, or both make financial deals more costly to govern. Governance costs increase in part because greater informational differences present possibilities of both adverse selection and moral hazard, as explained later in this chapter. The effects of such phenomena can be partially offset by additional governance capabilities, but acquiring such capabilities is costly, as will be discussed further below.

7.2.3.2 Asset Liquidity

Asset liquidity makes a considerable difference as to whether a financial deal can be classified as simple or complex. If the underlying assets can readily be traded in secondary markets, financiers have two potential sources of repayment. They can recoup their investment with interest if the firm or project being financed turns out well and generates a sufficiently large cash flow. If the firm or project cash flows do not materialize, liquid assets can still be sold to recover at least some of the funds initially put up. In such cases the deal is relatively simple. But if the assets are illiquid, financiers can only expect to recover a return on their investment by working to ensure that the project will operate profitably. Moreover the less liquid the underlying assets, the less the financier can rely on them as a source of repayment.

As will be discussed further below, asset liquidity will not necessarily remain constant over time. Indeed, liquidity depends primarily on the presence of both buyers and sellers. If there are only buyers in a market, there will be an asset demand but no compensating supply, whereas if there are only sellers in a market, there will be an asset supply but no compensating demand. Illiquidity becomes most widespread in markets where asset values can be affected in an uncertain manner by the actions of third parties, as will be discussed further in the next section. A potential buyer and a potential seller will find it difficult to agree on terms if the value of the asset they are attempting to exchange can be affected by the actions of a third party, and if those values are difficult for the potential counterparties to predict.

7.2.3.3 Risk versus Uncertainty

A second important attribute of a financial deal is whether its payoffs can usefully be described quantitatively using a probability distribution. If the expected earnings of a financial deal can usefully be described in probabilistic terms, the financial deal can be called risky. Two of the major risks associated with risky financial deals are profitability risk and default risk. Profitability risk refers to the probability of earning a relatively low return on the investment. Default risk refers to the possibility that a lender or investor faces the risk of the borrower not satisfying the terms of the contract, including both repayment of the amount invested and any accrued interest.17

Although profitability risk and default risk can be closely related, it is useful for descriptive purposes to distinguish them henceforth. Profitability risk depends mainly on such features of a financial deal as the possible magnitude of fluctuations in realized earnings, the maturity or termination date of the financial deal, whether the interest rate on it is fixed or floating, and the currency in which the financial deal is expressed. Default risk depends mainly on the probability that cash flows, including any cash that might be raised from selling assets, will be too small to permit making the contracted repayments on the debt. Financial deals that involve financing the purchase of liquid assets are less likely to pose default risk because liquid assets can be seized and sold to repay at least part, and perhaps all, of a loan or investment.

In another type of financial deal, it may not even be possible to quantify the factors critical to profitability. Consider, for example, the press reports of profitability estimates for the Channel Tunnel project connecting England and France that started in 1988 and began operations in 1994. This project's expected profitability changed considerably with the passage of time, even after allowing for some ability to recoup cost overruns through higher toll charges. The range of profitability estimates depends mainly on such variables as the demand for tunnel services, the reactions of competitors, global interest rates, and the like. Even sophisticated profitability models are not very helpful, since they depend critically on assumptions that are extremely difficult to render precise. Moreover, the Channel Tunnel's assets are illiquid, and therefore provide little in the way of collateral against default. That is, the Channel Tunnel's financing essentially represented a financial deal struck under conditions of uncertainty.

Uncertainty means that an economic agent cannot regard himself as understanding a financial deal well. Financial deals most likely to present uncertainty are those involving either a strategic change in business operations, or those financing a technological innovation. A start-up investment in a new, high technology business offers an example of a deal under uncertainty. It is often observed that such projects are particularly difficult to finance, mainly because economic agents find it difficult to assess their likely payoffs. First, neither clients nor financiers may be able to determine a proposed financial deal's key profitability features. Second, the possible reactions of competitors to carrying out the project may be difficult to predict. Despite these difficulties, financial deals presenting uncertainties are the essence of both business and financial innovation, and analyzing how financiers overcome the difficulties is profoundly important to studying financial activity.

Financial deals presenting uncertainties require different governance capabilities than do their merely risky counterparts. First, their successful governance requires greater adaptability to circumstances that are not easy to see when financial deals are first entered. Financial deals entered under uncertainty will require relatively more monitoring, especially if relevant information is likely to be revealed gradually with the passage of time. Moreover, if monitoring indicates that contract adjustments would be in order, the deal terms need to provide for those adjustments, or even for control of underlying operations as and when the needs for change are revealed.18 As a result, financiers often have to use incomplete contracts when entering deals under uncertainty.

7.2.3.4 Informational Differences

Financiers and clients do not always have the same information about a financial deal. When there are information differences, economists refer to this situation as informational asymmetries, a term used in contract theory where in a financial deal one party has more or better or different information than the other party.19 Information asymmetries can arise either because the two parties do not have access to the same data, or because they interpret the same data differently. Differences in interpretation can stem from differing levels of competence, or because differing experiences bias the parties’ respective views. In addition to views about the financial deal itself, economic agents may form views of how counterparties regard the financial deal, complicating the picture further. Thus, a deal's informational attributes can be classified according to whether agents perceive the risks or uncertainties symmetrically or asymmetrically. Moreover, the information differences between the two may change significantly during the life of a financial deal.

As a result of information asymmetries, there may be two types of problems in financial deals: adverse selection and moral hazard. Adverse selection in terms of financial deals means the negotiation of inferior terms relative to what would have been consummated if financiers (the “ignorant party” in the financial deal) had access to the same information as a client.20 Moral hazard in the case of a financial deal means that the ignorant party (the financier in the deal) does not have either (1) sufficient information about the performance of the client to evaluate whether the client is complying with the terms of the deal or (2) the capability to effectively remedy situations where the client has breached the terms of the deal. The classic example is in risk sharing, which as explained is one of the functions of a financial deal. An individual with insurance against the theft of jewelry may not be as careful about safeguarding the insured property because the adverse consequences of its loss are principally borne by the insurer.

Informational differences usually occur in financial deals that do not receive intensive study by a number of economic agents. Even in routine public market transactions, not all parties obtain the same information at the same time. Informational differences can even impede large public market transactions if the firm involved is changing the nature of its business. In both the United States and Canada, stock market trading activity by corporate officers and market specialists based on inside information has been shown to yield abnormal risk-adjusted returns. Whatever the likelihood of informational differences in public market transactions, they are even more likely to occur in private markets or in intermediated transactions. For example, financiers are well aware that some clients will provide biased information in attempts to improve financing terms.

Whenever informational asymmetries are perceived to have economically important consequences for a financier, attempts will be made to obtain more information, at least if the information's value is expected to be greater than the cost of gathering it. Cost-benefit analysis of information acquisition can be a challenging task under risk, and is even more so under uncertainty. In the latter case, financiers may not even know how to frame relevant questions regarding any benefits to gathering more information.21

7.2.3.5 Complete versus Incomplete Contracting

In risky financial deals, the financier's main function is to determine the market price of the assets involved, mainly by using information publicly available to market participants. Such financial deals normally require only a minimal degree of subsequent monitoring, since their terms can be specified relatively completely at the time when funds are first advanced. Financial deals of this type are said to use complete contracting.

Only some financial deals can be formalized using complete contracts. Complete contracting is a situation under risk in which all important outcomes can be described fully, and a situation in which actions to be taken can also be described fully, at least on a contingency basis. Some market deals can be described as complete contracts because they have little need of ex post monitoring. In some other market deals ex post has little value because the monitor has no real capability to effect any necessary changes.

Financial deals under uncertainty are often characterized by incomplete contracting, which refers to situations in which not all important outcomes can usefully be described in terms of a probability distribution. An example of incomplete contracting that arises from a conflict of interest is one between entrepreneurs and outside investors.22 Consider a situation in which the nature of the conflict cannot satisfactorily be resolved by specifying entrepreneurial effort and reward. To complicate situation further, entrepreneurial effort cannot always be modeled satisfactorily in a quantitative manner. And nor can entrepreneurial effort always be motivated by an incentive scheme: In some cases, it can only be motivated by financiers’ threat to liquidate/terminate the financial deal. When earnings prospects are good, the entrepreneur decides whether or not the profits from expansion are worth the effort she must supply. At the same time, if outside investors perceive the earnings prospects as bad, they may sometimes want to liquidate the company when the entrepreneur perceives expansion possibilities to be attractive. Such situations reflect some of the complexities of incomplete contracting.

7.2.4 Alignment

Financiers have specialized capabilities and accept deals whose attributes they can govern effectively. Relatively simple23 deals are usually agreed upon with market agents, while more complex deals are usually agreed upon either with intermediaries or, in extreme cases, internally to the funding organization. Thus, financier capabilities and deal attributes are aligned on the basis of cost-effectiveness. In the aggregate, the specialized capabilities of financiers and the financial deals they agree upon determine the mix of a given financier's business. The numbers and kinds of business organizations formed to carry out financial deals ultimately determine the nature of financial system organization.

7.2.4.1 Principles

Alignment decisions depend importantly on the kinds of specialized capabilities needed to govern a financial deal cost-effectively. Information about some kinds of deals may be fully available when a financial deal is first prepared, but in other cases pertinent information about the financial deal may also be gained during the time it remains in force. Moreover, in unfamiliar financial deals, financiers may learn how better to govern a financial deal over the time when it remains in force. Financial deals for which learning is important are usually agreed upon either with financial intermediaries or internally to the business firm, because in these cases it can be easier to adapt the terms of the financial deal as learning takes place. The incomplete contracts created are evidence that such financial deals are not usually traded, but are retained by the original lender until the funds advanced have been repaid.

Jensen and Meckling (1976) help illuminate choices among different forms of financial governance. They refer to knowledge that is costly to transfer among economic agents as specific knowledge, and knowledge that is cheap to transfer as general knowledge. Financial deals whose governance requires specific knowledge are more difficult to arrange than are financial deals whose governance requires only general knowledge. For example, a financial deal whose governance requires specific knowledge is more likely to be held by the originating financial institution rather than being traded in the marketplace, partially because the skills of the personnel originating the financial deal are more likely to be used in its continuing administration.

The packaging of loans (i.e., groups of financial deals) by a financial institution and the sale of securities backed by those loans is one financial technology that helps deal with the difficulties of transmitting specific knowledge. The process of packaging financial deals is referred to as securitization and the securities created are referred to as asset-backed securities. The original loans have idiosyncratic characteristics that represent specific knowledge, but the asset-backed securities issued against the portfolio of original loans are tradable instruments because investors in these instruments need only general knowledge about portfolio characteristics when they decide whether or not to invest in them. Making sure the portfolio retains its value is usually a job for the original lender, who has specific knowledge of the transaction details involved.24

Decision makers are constantly assembling new knowledge, and Jensen and Meckling argue that the more specific the assembled knowledge becomes, the more costly its transfer and the greater the likelihood it will be retained within the producing organization. Jensen and Meckling also point out that the initial costs of acquiring idiosyncratic knowledge (learning) can be modest, but the costs of transferring it can be high relative to the benefits. Uncertainty about what pieces of idiosyncratic knowledge might prove valuable ex post can actually present high ex ante transfer costs, in part because uncertainty implies a need to transfer knowledge that might never turn out to be useful. Thus, idiosyncratic knowledge is also likely to be retained within the producing organization.

To enhance the safety and profitability of a financial deal, financiers typically want to exercise more intensive governance capabilities if a project has uncertain rather than risky returns. When facing uncertainty, financiers (if they agree to put up any funds at all or to insure a financial deal) will try to discover and manage a financial deal's key profitability features. But since they cannot specify exactly what might be required in advance, financiers can only formalize their loan agreements to the extent of citing principles that allow them to respond flexibly to changing conditions. That is, financiers use incomplete contracts to govern the uncertainties with which they grapple. If relatively precise specifications were possible, financiers could write complete contracts when financial deals were agreed upon.

Contrast a public issue of stock with a financing arrangement that a conglomerate headquarters might strike with one of its subsidiaries. In the first case, information is widely shared by many parties; in the second case (internal governance), it is not. Moreover, in the second case, there are much greater opportunities for continuing supervision after financing has initially been provided. Finally, in contrast to a public securities issue whose features are explained in a publicly distributed prospectus,25 internal governance may be used to keep information about development plans from being revealed to competitors.

7.2.4.2 Process

Financiers attempt to make alignment choices as cost-effectively as they are able, and Table 7.3 shows how alignments can be regarded as the results of an interplay between clients presenting deal attributes and financiers’ possessing governance capabilities. The financing costs that clients face, and governance costs that financiers incur, are determined as a result of the interplay. The first section of Table 7.3 arranges the three basic governance mechanisms—financial markets, financial intermediaries, and hierarchical arrangements such as internal financing, in increasing order of command-control intensity. For example, public markets are recorded to the left of private markets, because private market agents can muster certain governance capabilities not possessed by public market agents. Private market agents usually have greater investigative capability, and in some cases greater freedom to negotiate terms, than do public market agents. Similarly, even though commercial banks and venture capital firms are both intermediaries, commercial banks usually have less highly developed screening and monitoring capabilities than do venture capital firms. In particular, venture capital firms make greater use of discretionary arrangements, which usually include obtaining a seat on the board of any company to which they extend funds. Finally, hierarchical governance means governance within a given organization or group. Western financial conglomerates sometimes offer examples of hierarchical organizations, as do the Japanese keiretsu.26 Similarly, the universal banks27 found in Germany use something closer to hierarchical governance when they both purchase the shares of, and make long-term loans to, the same clients.

TABLE 7.3 GOVERNANCE CAPABILITIES, DEAL ATTRIBUTES, AND ALIGNMENT

The second section of Table 7.3 indicates that different governance mechanisms can exercise differing degrees of capabilities. For example, internal financing arrangements have greater monitoring and control capabilities than market arrangements. The governance cost section of Table 7.3 is a reminder that greater capabilities cannot be acquired without incurring additional costs.

Reading from left to right in the attributes section of the table shows that deals characterized by greater informational differences between the two parties (the financiers typically having less information) are viewed by financiers as involving higher degrees of risk, or as presenting uncertainty instead of risk. Higher-risk financial deals, and financial deals whose prospects are uncertain, pose greater needs for continuing governance than do lower-risk financial deals. Similarly greater uncertainty, a lower degree of asset liquidity or both make it more difficult to establish market values for the underlying assets. Difficulty in establishing market value leads to difficulty in determining the breakup value of a firm when in financial difficulty. If financiers cannot readily establish a breakup value for the firm, they do not know what they might be able to recover from a sale of assets if the firm should fail. Therefore, financial deals with such firms appear riskier than, say, financial deals that involve financing the purchases of liquid assets with readily established market values.

Financings under uncertainty present the most difficult governance problems, and are therefore likely to be subjected to the most intensive forms of governance. Of course, greater capabilities come at greater costs, and these governance costs must be recovered from gross returns on the investment. For example, administering a portfolio of short-term liquid securities principally requires market governance, while administering the financing of conglomerate subsidiaries that are entering new ventures can require a much more intensive, higher capability form of governance. As a result, the second kind of financial deal must offer higher gross returns if it is to be regarded as capable of generating expected net profits.

7.2.4.3 Cost-Effectiveness

Financiers accept a financial deal on the basis of whether they regard themselves as having the capabilities to govern the financial deal profitably. They reject financial deals that do not meet such criteria. Expected profits depend both on the revenue from the financial deal and the cost of its governance. Financiers strive to control costs by only taking on those financial deals they can govern cost-effectively, as illustrated by the arrangements in the different parts of Table 7.3. For example, in comparison to intermediary or hierarchically governed deals, market financial deals tend to be more standardized, and to exhibit less important informational differences between client and financier. As a result, market governance uses relatively few monitoring and control capabilities, and market-governed deals typically present lower administration costs than do hierarchically governed deals. A market agent will not usually take on financial deals that require the specialized governance capabilities of a financial intermediary.

Market governance is generally cheaper than hierarchical governance.28 In governing standard deals arranged under competitive conditions there is little room to cover the extra resource costs of hierarchical governance, and risk reduction has little importance for assessing profitability. It follows that the profitability29 of doing a standard deal using market governance usually exceeds the profitability of doing a standard deal using, say, intermediary governance. If intermediaries were to take on such deals, they would do so primarily because they could exercise additional governance capabilities. In such cases, their loan administration costs would be higher than the administration costs of market agents, and the intermediaries would have to charge a higher interest rate to cover the costs.

A form of non-arm's length governance can be a cost-effective alternative to market governance if the benefits of additional monitoring, control, and adjustment capabilities exceed the extra information and monitoring costs involved. Hierarchical governance is especially likely to be cost-effective when the financing environment is uncertain. The reduced risk or increased return from hierarchical governance more than compensates for the greater cost of acquiring the extra governance capabilities.

On the demand side, clients attempt to seek out a financier who offers the most attractive terms available. Clients strive to minimize their costs of obtaining funds, but they will not always find the best available deal terms. For example, a client will not willingly pay a higher fee to an intermediary than the client would have to pay to a market agent. Yet if search costs are high, a client will quite often accept one of the first few feasible arrangements the client can find, maybe even the very first. That is, high search costs bias clients toward exploring familiar sources of funding.

Nevertheless, a client may be able to secure several offers of financing. For example, a client seeking external financing will choose, frequently in consultation with one or more financiers, whether to offer securities in a public marketplace or through private negotiations. The client's eventual choice will depend on the terms offered, including interest costs, the amount of information required to be provided, the parties who will become privy to the information, and the effects of information release on the client's competitive position.

7.2.4.4 Asset Specificity

Williamson (2002) models the complementarities of governance structures as a function of asset specificity. Although the two concepts are not identical, for most purposes asset specificity can be thought of as similar to asset illiquidity. Figure 7.1 shows the transactions’ cost consequences of organizing financings through markets, through financial intermediaries such as banks, and through financial conglomerates when the transactions vary by asset specificity. Increasing asset specificity is plotted toward the right of the horizontal axis, and costs are plotted on the vertical axis.

FIGURE 7.1 COMPARATIVE COSTS OF GOVERNANCE

When assets have a low degree of specificity, the bureaucratic costs of financial conglomerates place them at a serious disadvantage relative to markets. Similarly the bureaucratic costs of banks place them at a disadvantage relative to markets, albeit a lesser one than conglomerates. However, the cost differences narrow and are eventually reversed as asset specificity increases. Intermediaries are therefore viewed as a hybrid form of governance structure that possesses capabilities somewhere between those of markets and those of conglomerates. With an increase in asset specificity, intermediaries come to offer a cost advantage relative to markets, and as asset specificity increases further still, conglomerates come to offer a cost advantage relative to intermediaries. Because added governance costs accrue on taking a transaction out of the market and supervising it with an intermediary or conglomerate organization, the three are usefully viewed as complements, the more expensive to be substituted for the less expensive as the degree of asset specificity increases. Cost-effective governance choices mean the effective form of cost curve in the circumstances displayed is the envelope reflecting the minimum of the three cost curves displayed.

7.2.4.5 Deal Terms

Financiers propose varied deal terms, both in attempts to ensure profitability and to fine-tune governance arrangements. The terms of a financial deal include repayment arrangements, the collateral taken, the currency used, and its maturity (fixed or variable). Along with the amount advanced, these terms also determine the effective interest rate. The effective interest rate on a financial deal increases with its risk, and will be higher for uncertainty than for risk, because financiers require larger returns to compensate for greater risks or for assuming uncertainty rather than risk.30

Terms can alter the nature of a financial deal's original attributes. For example, a deal offering uncertain payoffs can be much easier to finance if the client can offer marketable securities as collateral. In this case, a loan can be made against the value of the securities, and the financier, who can rely on the securities’ market value as collateral for the loan, will likely view the deal as merely risky rather than uncertain.

How the terms of a financial deal can perfect the capabilities utilized in its governance is explained in Web-Appendix A. In particular, the informational conditions under which a deal is originated, and the likely evolution of that information, have important implications for selecting deal terms.

7.3 FINANCIAL SYSTEM ORGANIZATION

There will usually be a least-cost form of governance for each type of financial deal. Over time, competitive pressures will create a tendency for a least-cost form of governance to emerge for financial deals of a given type. Nevertheless, financiers can sometimes earn above-normal profits31 on complex financial deals (even after adjusting for differences in risk) because the markets in which some deals are agreed can be less competitive than the markets for more straightforward deals.

A financial firm's size and organization are determined mainly by the economics of the financial deals they take on, and by their operating economics. Scale and scope economies are important features of the latter. Scale economies refer to the ability to produce additional units of output at a decreasing average cost per unit, and frequently arise from spreading fixed production costs over a larger number of units of output. Scope economies refer to the ability to obtain combinations of goods or services at a lower average cost per unit than can be achieved if the goods or services are produced individually. Scope economies, sometimes called cost complementarities or synergies, frequently stem from the ability to share common inputs.

7.3.1 Markets, Intermediaries, and Internal Finance

The alignment of financial deal attributes and governance capabilities, and the consequent assembly of portfolios to take advantage of the associated firms’ operating economies, explain the static organization of the financial services industry. If there were no financial intermediaries, potential borrowers would individually have to seek out willing lenders. Similarly, lenders would individually have to screen borrowers, design financial contracts, and monitor borrower behavior. When financial intermediaries perform the same functions, they may be able to do so more economically by realizing scale and scope economies in their operations. Carey, Post, and Sharpe (1998) argue (1) that markets and intermediaries make different types of corporate loans, and (2) that within the class of intermediaries differently specialized firms make different types of corporate loans. Their evidence further implies that it is not enough to understand the mixture of debt obtained by from public markets and private markets; what also matters is the mixture of the varieties of private debt.

Boot and Thakor (1993) model private banking markets as less competitive than public securities markets. In their model, greater interbank competition reduces banking rents and makes banks more like each other and less likely to specialize. Increased capital market competition tends to reduce both banking rents and entry to the banking industry. Boot and Thakor believe the distinctions between banks and financial markets are likely to become increasingly blurred, but the perspective of this chapter suggests that there will continue to be differences between different types of financial deals, and therefore, different kinds of governance mechanisms will continue to be needed for their administration.32

In the aggregate, the organization of a financial system reflects a mix of alignments among the types of deals agreed upon and the capabilities of the economy's financiers. The size of an individual firm is determined by its operating economics. In addition, there is a natural evolution of any particular deal type from the right to the left in Table 7.1 that is due to financier learning, increasing volume of deals, standardization of deals over time, and more nearly precise and cheaper information production. At the same time, a continual infusion of new financial deals means that high capability governance continues to be needed, even in advanced economies. The proportions of deals governed as market arrangements may change relative to the proportions governed by intermediaries or internally, but all three types of governance will continue to be needed.

7.3.2 Financial Firms

Financial firms assemble agreed financial deals into portfolios whose size and composition are determined by the firms’ operating economics. Financiers specialize in particular types of deals as a means of realizing scale economies in both screening and information production. They realize additional scale economies by increasing the numbers of financial deals in their portfolios, and scope economies by taking on related types of financial deals. In other words, these actions reduce unit costs and, if unit revenue remains the same, profitability is improved.

Limits to the size of a financial firm depend mainly on the costs of coordinating the governance of different types of financial deals. When coordination costs begin to rise on a unit basis, taking on more business generating the same unit revenue means that the profitability of additional business begins to fall. When incremental profitability falls to zero, it is uneconomic for a financial firm to take on still further business: Firms can be expected to grow only until coordination costs become large enough to impair the profitability of taking on more financial deals.

There are several economic reasons for specializing. First, specialized skills and experience may be required in order to be able to do financial deals profitably, and only a few intermediaries can justify incurring these expenses. For example, some banks specialize in foreign exchange transactions involving their home currencies, while other banks trade in most major foreign currencies. Second, certain types of financial deals can only be done in relatively small volumes, so that only a few firms can profitably service that market. Venture capital investments offer a case in point. Third, regulation may restrict intermediaries to only certain types of transactions.

On the other hand, there can also be advantages to diversification. When a firm assumes a greater number of financial deals, as well as when it assumes additional types of financial deals, it can usually diversify portfolio risks.33 Since diversifying portfolio risk reduces earnings risk relative to the expected level of earnings, the firm's performance is thereby improved.

7.3.3 Combinations of Mechanisms

There are many instances of governance mechanisms being combined. For example, an intermediary can partially diversify its asset portfolio by issuing securities backed by some of its loans (securitization) and using the proceeds to purchase other unrelated securities. Usually, intermediaries use the funds raised from securitization to fund more of the same type of lending. Nevertheless, some potential for unbundling remains: A bank may have a competitive advantage in screening and monitoring, but an insurance company or mutual fund may have a competitive advantage in raising funds for investment purposes.

Banks can complement the workings of the securities markets in other ways as well. For example, certifying the creditworthiness of borrowing customers makes it easier for those borrowing customers to avail themselves of additional capital market financing.34 Banks also assist their customers to obtain less costly capital market financing by providing guarantees, particularly in circumstances where a bank might have a competitive advantage in determining a client's creditworthiness.

Intermediaries also provide services that are not reflected on their balance sheets. Traditionally off-balance sheet activities included providing letters of credit, and now include such other activities as arranging risk management services using derivative instruments. In some risk management transactions, corporations can use exchange-traded instruments, but in others they deal with intermediaries that trade the instruments on an over-the-counter basis. The difference in the types of transactions depends on whether it is securities markets or intermediaries that offer a competitive advantage; this in turn depends on the type of instrument, its complexities, and the creditworthiness of the parties involved.

KEY POINTS

- The functions performed by every financial system include clearing and settling payments, pooling resources, transferring resources, managing risks, producing information, and managing incentives.

- Some financial system functions—pooling resources, transferring resources, and managing risks—require special attention because they involve either the commitment of financial resources over relatively long periods of time, significant transfers of risks, or both.

- If financial deals are to work out profitably, they need to be governed appropriately, and the most effective financial system governance mechanisms depend on both the capabilities of the accommodating financier and the attributes of the financial deals themselves.

- The mechanisms for governing financial deals are variations of financial market, financial intermediary, and internal arrangements.

- Financial market governance works best when a financial deal's essential attributes can be captured by the funding cost it bears and within this category of governance distinctions can be made on the basis of differences in the capabilities of market agents.

- Financial intermediaries are enterprises that raise funds from savers and relend the funds to business and personal borrowing customers.

- Financial intermediaries exercise certain kinds of governance capabilities that are not customarily utilized by market agents (more intensive ex ante screening capabilities of borrower and more extensive capabilities for monitoring, control and subsequent adjustment of financial deal terms) producing cost-effective ways for governing the financial deals they enter.

- Internal governance (also referred to as hierarchical governance) involves financial resource allocation using command and control capabilities to a still greater extent than that used by financial intermediaries, offering the greatest potential for intensive ex ante screening, ex post monitoring, control over operations, and adjustment of financial deal terms.

- The focus of internal governance is more on the command and control mechanisms that can be employed to effect ex post adjustment of financing terms than on the nature of a financial contract itself.

- Internal governance is likely to be more expensive than governance by financial market or financial intermediaries, and as a consequence will normally be used to govern financial deals whose uncertainties are greater than those acceptable to financial intermediaries.

- Financial deals can be described as different combinations of the basic attributes: asset liquidity, risks, information asymmetries, and complete contracting.

- Once an alignment of financial deal attributes and governance capabilities has been reached, the actual tasks of governance typically involve developing transaction information and managing incentives. However, these tasks receive different emphases according to the financial deal's attributes.

- Financial system organization is influenced by the economics of performing basic functions, by the economics of governing deals, and by the operating economics of the institutions that group financial deals together.

- Both the functional and the governance approaches contend that financial deals of particular types are governed as cost-effectively as possible, subject to the limitations imposed by current financial technology.

- Financial firms with particular governance capabilities usually specialize in financial deals with particular attributes, because that is how the firms can utilize their resources most effectively. The sizes of financial firms are determined by their cost and profitability characteristics.

- Financiers have sharply varying capabilities for funding projects that are backed by uncertain earnings, illiquid assets, or both.

QUESTIONS

- What are the components of a financial system?

- Explain each of the major financing mechanisms found in financial systems.

- What is meant by risky financial deals?

- What is meant by financial governance within the financial system?

- Explain why market governance works best when the essential attributes of a financial deal are incorporated into the funding cost associated with the risk borne by investors.

- The following excerpts are taken from Reinhard H. Schmidt and Aneta Hryckiewicz, “Financial Systems—Importance, Differences and Convergence,” Working Paper Series No. 4 (2006), Institute for Monetary and Financial Stability:

In most economies, many financial decisions and relationships of the households and the firms involve banks, capital markets, insurance companies and similar institutions in some way. In their totality, those institutions that specialize in providing financial services constitute the financial sector of the economy. Of course, the financial sector is a very important part of almost any financial system. But it should not be taken for the entire financial system. Only some 15 years ago, there were some parts of the so-called developing world and some formerly socialist countries in which almost no financial institutions existed or operated, and still people saved, invested, borrowed and dealt with risks in these countries and regions. Thus there can in principle even be financial systems almost without a financial sector. But also in advanced economies, many financial decisions and activities completely bypass the financial sector. Examples are real saving, self-financing and self-insurance and informal and direct lending and borrowing relationships.

- Explain how “real saving, self-financing and self-insurance and informal and direct lending and borrowing relationships” are examples of bypassing the financial sector.

Most theoretical models presented in the literature focus either on banks or financial markets, and they emphasize either the function of fostering capital accumulation or that of promoting innovation and increasing the productivity of the use of capital.

- Explain the two functions in the preceding quote.

Some contributions point out that banks can have some positive effects or perform certain functions very well, while markets are good at performing other functions well. As an example, banks seem to be particularly good at creating and using private information. On the other hand markets seem particularly well suited to aggregating diverse pieces of public information.

- Explain why banks and markets perform their respective functions well.

The statistical data and the descriptions of national financial systems … show two trends that seem rather contradictory. One is that in almost all financial systems the values taken on by those financial sector indicators that represent the role of capital markets increase over time. This suggests a tendency of a general convergence towards the Anglo-Saxon model of a capital market–based financial system, although this is no conclusive evidence since systems are more than collections of individual elements. The other trend is that in many countries the characteristics remain largely intact. As the descriptions show, the German financial system still seems to be bank-dominated, and the Anglo-Saxon countries USA and UK still have capital market–dominated financial systems.

- What is meant by a “capital market–based financial system” and “bank-dominated” financial system?

- Explain how “real saving, self-financing and self-insurance and informal and direct lending and borrowing relationships” are examples of bypassing the financial sector.

- The following excerpts are from Section 802 of the U.S. Payment, Clearing, and Settlement Supervision Act of 2009:

- The proper functioning of the financial markets is dependent upon safe and efficient arrangements for the clearing and settlement of payment, securities and other financial transactions.

- Financial market utilities that conduct or support multilateral payment, clearing, or settlement activities may reduce risks for their participants and the broader financial system, but such utilities may also concentrate and create new risks and thus must be well designed and operated in a safe and sound manner.

- Payment, clearing and settlement activities conducted by financial institutions also present important risks to the participating financial institutions and to the financial system.

- Enhancements to the regulation and supervision of systemically important financial market utilities and the conduct of systemically important payment, clearing, and settlement activities by financial institutions are necessary to provide consistency, to promote robust risk management and safety and soundness, to reduce systemic risks, and to support the stability of the broader financial system.

- At a conference (“Perspectives on Managing Risk for Growth and Development”) held at the University of the West Indies on March 4, 2010, the following comments were made by Brian Wynter, a governor of the Bank of Jamaica:

Let me begin by emphasizing the critical importance of good risk management for the each firm, its industry and the economy as a whole and say that an efficient risk management system is one of the key ingredients for increasing the productivity of investment in Jamaica. Financial markets promote economic growth by channeling capital to the entrepreneurs with high-return projects. A robust and stable financial system capable of directing capital to its most efficient use is therefore a necessary condition for economic growth. The efficient allocation of capital underlies economic efficiency, international competitiveness, and economic stability. The level of efficiency of capital allocation derives in part from sound risk management.

As a financial system supervisor, the Bank of Jamaica is committed to facilitating sound risk management in the financial system. Our responsibilities are discharged by focusing on both firm-specific and system-wide elements, both of which support overall macroeconomic stability and growth.