24

FINANCIAL CONTRACTING AND DEAL TERMS

In Chapter 7, we described deal terms. Corporate management in need of external funds must design and negotiate terms with financiers. The formalization of the terms of the agreement between the supplier and demander of funds is memorialized in a contract. The process is referred to as financial contracting.1 The literature on financial contracting seeks to explain what kinds of deals are made between financiers and corporate management and helps us understand why different forms of contractual relations are observed in practice between firms and financiers (i.e., investor groups). Basically, financial contracting seeks the optimal security design for overcoming conflicts between financiers and those entities seeking funding. Much of the focus in the application of financial contracting has not been on large public firms but, instead, primarily on small entrepreneurial firms.

We first explain how the informational conditions under which a deal (i.e., a financing) is originated—and the likely evolution of that information—have important implications for selecting deal terms. When deals are arranged under risk, they can be formulated as complete contracts. In addition, when they are arranged under conditions of symmetric information, it is relatively easy to select appropriate terms. However, if the deals are arranged under conditions of information asymmetry, they usually present potential complications of moral hazard and adverse selection. Each can be governed effectively, but at the expense of incurring additional costs. Finally, when deals are arranged under uncertainty, the contracts are necessarily incomplete, and as a result their governance requires different methods and terms.

We also examine how deal terms are used to fine-tune agreements between a financier and the management of a firm seeking funding. The discussion emphasizes the financier's perspective, since typically a financier proposes a standard set of terms to be negotiated. If the management of a firm seeking funds finds the terms generally acceptable, management may propose additional negotiation to resolve any remaining differences. As negotiations proceed, the financier may also propose additional conditions intended to enhance the deal's safety, profitability, or both. Finally, if both parties are agreed on the conditions, the deal will be struck and the financing extended.

24.1 COSTS OF DEALS

Deals with differing attributes will usually be arranged at differing interest rates in order to compensate for the risk or uncertainty involved. The difference between the effective interest rate2 charged to a firm and the interest cost of funds to the financier will vary according to the deal's particular attributes, the governance capabilities of the financier, and the competitiveness of the environment in which the financing is arranged. For example, a market exchange of bonds is usually a risky deal based on information publicly available to both parties. In such a transaction the difference between financiers’ total interest cost and the effective rate paid by the firm will not usually be large, especially if the market is competitive. On the other hand, financing a new business venture represents a deal under uncertainty, and the parties are likely to have quite different information about possible payoffs. The interest premium for facing uncertainty, and for incurring transactions and information processing costs, is therefore likely to be greater—in some cases very much greater—than in the bond deal. Moreover, the markets for financing business ventures are not as likely to be competitive, meaning that financier profit margins will likely be higher than in the first example.

24.1.1 Transactions Costs

The client seeking financing considers both direct and indirect costs in assessing a deal's total transactions costs. Direct costs are those the client pays to the financier. Indirect costs are those paid to others, but the outlays still comprise part of management's expenses. For example, the owner of a small business might look long and hard to find someone interested in investing long-term capital in his business, and would have to bear the costs of continuing to search for an accommodating financier until one is found.

From the financier's point of view, a deal's costs include the financier's costs of raising the funds, the marginal costs of assessing the deal, a contribution to the financier's fixed costs, and an allowance for a profit margin. The magnitude of the charges depends on the financier's efficiency, the competitiveness of the market served, and the kind of deal information that must be obtained, both at the outset when the deal is being negotiated (ex ante information obtained by screening) and subsequently as the deal is being worked through (ex post information obtained from monitoring). If a financier is to stay in business over the longer term, all costs must be recovered, whether through interest charges, explicit fees, or a combination of the two.

24.1.2 Screening and Monitoring Costs

Screening costs are the ex ante costs a financier incurs to assess a funding proposal, while monitoring costs are the ex post costs involved in the deal's continuing governance. Since screening costs are usually the sum of a fixed set-up cost and an ex ante variable cost, the average cost of screening individual deals can be expected to decline as the number of deals screened increases. The same is likely to be true of monitoring costs.

The average cost of administering a deal is the sum of its screening and monitoring cost, along with the cost of making any adjustments that monitoring indicates would be desirable. While scale economies explain why this average cost function will likely decline with transaction volume, other factors can affect the function's position and how it is likely to shift. First, the position of the screening cost function will be higher for deals with greater informational differences between clients and financier. Second, the screening cost function may shift downward as financiers gain experience with a particular type of deal and, thereby, learn how to screen it more efficiently. Monitoring costs differ according to the kinds of informational differences involved, and a financier's monitoring cost function can also shift as a result of learning. Finally, as shown in both this chapter and in Chapter 21 where we discussed markets with impediments to arbitrage, both screening and monitoring costs can be greater in deals where it is necessary to manage the effects of asymmetric information.

The potential volume of a given deal type is determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves for the financing type. If demand from businesses is relatively great, many deals are likely to be completed, and per deal screening costs will be low because financiers can take advantage of both scale economies and learning effects. However, the economics of screening can work to deter the entry of a new supplier to a market, especially if the cost function shifts downward as the number of completed deals increases. In such circumstances, the financier who first enters a market can gain a first mover advantage over subsequent entrants, particularly if the skills the financier acquires are experiential and therefore difficult to communicate.3 Potential new entrants may not be willing to set up innovative financing arrangements because they see existing financiers as having entrenched advantages that are difficult to overcome.

The economics of screening can also work to inhibit the viability of new deals. First, financiers have to incur costs to determine whether the deal is viable. Moreover, financiers’ perceptions of economic viability depend in part on the skills they have already acquired. To illustrate, there are high fixed costs to setting up venture capital firms, both because the personnel in a new firm need to learn how to screen prospects, and because any one person can only supervise a limited number of venture investments. Even if a venture firm has some personnel with screening experience, their skills are acquired principally through experience rather than in a classroom setting. As a result any new employees have to gain similar experience, and at any given time existing firms may not be able to accommodate the entire market's demands for financing. Nevertheless, unless there is enough unsatisfied demand to cover the fixed costs of setting up a new firm, the supply deficiency may persist.

24.2 INFORMATIONAL CONDITIONS

The information available to a financier affects his estimate of a deal's profitability and determines the kinds of reports he will require from the client. When financiers take on familiar deals, they are likely to treat the transactions routinely, especially in the absence of informational asymmetries. For example, the purchaser of a U.S. Treasury bill has access to almost all potentially relevant information when the purchase is made. On the other hand, the venture capitalist investing in a growing firm has much less precise ex ante information, particularly when the firm's principal asset is the talent of its owner-manager. Moreover, the venture capitalist is much more likely to refine ex post estimates of firm's potential profitability over the investment's life than is the purchaser of a Treasury bill.

If a financier has less information than her client, she will try to determine whether it is cost-effective to obtain more details. If he thinks it would be, he may incorporate his informational requirements in the terms of the deal, as illustrated later in this chapter when we discuss the renegotiation of a bank loan. Some information may be available ex ante while other information may only be obtainable ex post. For example, a retail client borrowing against accounts receivable might be asked to submit quarterly statements of accounts receivable outstanding, thus keeping fresh the lender's information about the quality of the security.

24.2.1 Information and Contract Types

As Table 24.1 indicates, financiers select governance mechanisms according to each deal's informational conditions. Deals arranged under risk are easier to govern than deals under uncertainty, because they present situations in which complete contracting is possible. The terms of deals arranged under uncertainty cannot usually be specified quantitatively. For example, if the relevant states of nature are observable but not verifiable, it will not be possible to write a complete contract. In still more complex situations it may not even be possible to define the relevant states of nature.

Financings arranged under uncertainty usually provide for the exercise of discretion to compensate for contract incompleteness. For example, the arrangements may provide for relatively intensive monitoring over the deal's life, as well as for flexibility of response to evolving information. If an unforeseen contingency does occur, it may not have been possible to specify in advance what the appropriate adjustments would be.4 Basically, there is a relationship between management and financiers that is not static but changes over time. Over the course of time, future states of the world may be redefined, or contingencies may arise that could not have easily been foreseen at the time a financial contract was entered into. A contract between the parties that has these attributes (i.e., fail to specify all future contingencies and thereby the consequences to the parties) is called an incomplete contract. Many such incomplete contracts are expressed in terms of the principles to be followed in making adjustments if and when the need for them becomes apparent. Hart (2001) observes that one way of coping with such eventualities is through different forms of financial structure. For example, equity gives shareholders decision rights if the firm is solvent, but debt gives creditors those decision rights if the firm is in bankruptcy.5

TABLE 24.1 DEAL ATTRIBUTES AND GOVERNANCE STRUCTURES

| Informational Attribute | Governance Structure |

| Risk | Complete contract. Rule based; little or no provision for monitoring and subsequent control. |

| Uncertainty | Incomplete contract. Structure allows for discretionary governance. Details of monitoring and control are typically negotiated. |

Another possibility is that whatever financial instrument is used, a preamble to the contract may state principles for renegotiation under certain general conditions that by necessity cannot be well specified in advance since the future is “simply too unclear” (Hart 2001, p. 1,083). The possibility of renegotiation implies that financiers’ governance costs will increase, and the increased costs will only be warranted if financiers believe they can reduce possible losses at least commensurately. Financiers will also seek larger interest rate premiums for bearing what they perceive to be greater degrees of uncertainty, and will attempt to recover these costs and premiums from firms seeking funding. As a result, the firm presenting a highly risky deal can expect to pay a higher effective interest rate than a firm presenting a less risky deal, and a firm presenting a deal under uncertainty can expect to pay a higher effective interest rate than a firm presenting a deal under risk.

24.2.2 Informational Asymmetries

While informational asymmetries are not unknown in public market transactions, they have greater importance in private market and in intermediated transactions, mainly because they are more difficult to resolve in the absence of active market trading. Indeed, in intermediated transactions informational differences may persist even after intensive screening. First, financiers and a firm seeking funds may differ in their estimates of a deal's profitability, in part because they have different information processing capabilities. Second, the parties may have the same ex ante information about a deal, but their ability to keep informed about its progress may differ. Finally, financiers are well aware that firms seeking funds sometimes provide biased information in attempts to improve the financing terms they can obtain.

It is much more difficult to reach a satisfactory agreement when financiers and a firm seeking funds differ greatly over a project's viability than it is when they share the same view. If the asymmetries are great enough, it may only be possible to do the deal at nonmarket interest rates. In other cases, it may not be possible to reach agreement at any interest rate. For example, in the early 1980s opinion regarding the value of the troubled Continental Illinois Bank's loan portfolio varied so greatly that counter-parties found it difficult to agree on a mutually satisfactory price for the bank's shares. As a second example, the parties attempting to exchange mortgage-backed securities collateralized by subprime loan portfolios in 2007 and 2008 found that, as the instruments became increasingly illiquid, getting any estimate of the value of these securities was difficult.

Sufi and Mian (2009) explore some of the ways that information asymmetry influences loan syndicate structure and membership.6 First, lead bank and borrower reputation mitigates, but does not eliminate information asymmetry problems. Moreover and consistent with moral hazard in monitoring, the syndicate's lead bank both retains a larger share of the loan and invites fewer other syndicate members when the borrower requires more intense monitoring. When information asymmetry is potentially severe, accommodating lenders are likely closer to the borrower, both geographically and in terms of previous lending relationships. The models presented in the rest of this chapter further illustrate some of the ways financiers attempt to cope with the effects of informational asymmetries.

24.2.3 Third-Party Information

Financiers can sometimes reduce information costs through purchasing information rather than producing it in-house. Deal information will be provided by third parties if they can turn a profit doing so. For example, rating agencies like Moody's, Standard & Poor's, and Fitch monitor the creditworthiness of public companies’ debt issues and publish their ratings. Companies seeking funds will pay to be rated if by so doing they can reduce their financing costs more than commensurately. Benson (1979) argues that by producing bond rating information and then finding investors interested in purchasing the bonds, underwriters can reduce financing costs to less than they would be if buyers produced the information individually. In the United States, municipal bond insuring agencies serve as another type of information producer.

Even though information is collected and used privately by the insurers, other members of the investing public may interpret the issuance of an insurance policy as a signal regarding the municipality's creditworthiness. Similarly, Fama (1985) argues that short-term bank lending may signal a borrowing firm's quality, and that a bank's willingness to extend short-term financing may reduce the firm's total financing costs. As still another example, when a portfolio of loans is securitized, it is quite common for a third party to insure the securities issued against such events as default on their principal amount. In effect, the insurance amounts to a third-party rating of the default risk in the loan portfolio backing the issuance of the new instruments.

24.2.4 Asymmetries and Financing Choice: Debt versus Equity

Many writers have addressed the question of why firms use both debt and equity financing. The famous Modigliani-Miller (MM) theorem establishes conditions under which there is no advantage to using one rather than the other. Recall that MM argue that if there are no taxes or bankruptcy costs to defaulting on debt, then financing with a combination of debt and equity rather than with equity alone adds nothing to the value of the firm. In the circumstances envisioned by MM, debt and equity are merely ways of dividing up cash flows and different ratios of debt to equity financing neither create nor destroy firm value. However, subsequent research recognizes that taxes, bankruptcy costs, and other forms of market imperfection can explain why corporate treasurers are not indifferent to the manner in which they raise long-term finance. That is, the costs of long-term finance can be affected by differing ratios of debt to equity when taxes, bankruptcy costs, and other market imperfections are recognized as elements of the financing picture.

Ross (1977) notes that firms used both debt and equity financing even before corporate taxes were levied. Ross suggests that different levels of the debt-equity ratio can reflect management attempts to signal the quality of their firms, and that management can be motivated to signal truthfully as long as they face appropriate incentives. He shows that debt with a fixed face value and a bankruptcy penalty7 is the optimal contract for maximizing a risk-neutral entrepreneur's expected return, given a minimum expected return to lenders. The Ross explanation is persuasive if management has personal resources to pay the bankruptcy penalties, but such a situation is not typical of an entrepreneur who has invested all available assets in his firm. In addition to Ross's explanation, debt-equity ratios can have value implications because they convey different control possibilities. Hart (2001) points out that while shareholders have decision rights as long as a firm is solvent, those decision rights pass to creditors when the firm is insolvent.

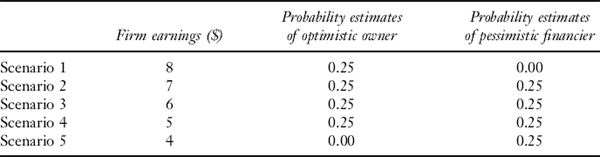

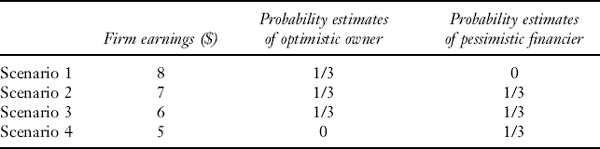

The next example shows still another effect, this time due to informational asymmetries: If financiers and entrepreneurs disagree regarding a firm's prospects, debt can come closer than equity to resolving their differences. The result is first demonstrated numerically and then considered a little more formally. Suppose both owners and financiers are risk neutral, and that interest rates are zero. Suppose also that the owners of a firm are optimistic, while financiers are pessimistic, in the sense reflected in Table 24.2. Owners expect firm earnings to be higher than do financiers; indeed, owners do not expect earnings of $4 can occur at all, and attach equal positive probability to the remaining four scenarios. Financiers do not expect that earnings of 8 are possible, but attach equal positive probability to the other remaining scenarios.

Next, consider the value of the equity in the firm, as viewed by the owner and the financier, respectively. The owner values the equity at ($8 + $7 + $6 + $5)/4 = $6.5, while the financier's value is ($7 + $6 + $5 + $4)/4 = $5.5. Nevertheless, both parties would agree that the firm's promise to pay 4 can be met all of the time and, therefore, both parties would place the same time 0 value on debt8 promising to pay $4 at time 1. That is, even though they do not agree on the firm's prospects, the two parties can agree on the value of at least this limited amount of debt.

TABLE 24.2 OUTCOMES AND PROBABILITIES

Now suppose the firm needs to raise $5, and that financiers have the power to set the terms on which they will purchase securities. If financiers were to purchase equity that they regard as being worth $5, they would demand $5.0/$5.5 or 10/11 of the shares. However, the owners regard 10/11 of the shares as having a value of ($6.5) (10/11), or $5.91. Thus, to the owners, equity financing carries a high implicit rate of return, even in the present case where interest rates have been assumed to be zero.

Alternatively, suppose financiers propose a debt issue that promises to pay off $5.5 if the firm has the funds, or whatever funds are available if the firm does not generate cash flows at least equal to $5.5. Financiers would value this debt at ($4.0 + $5.0 + $5.5 + $5.5)/4 = $5.00. The owners, who regard the debt as worth ($5.0 + $5.5 + $5.5 + $5.5)/4 = $5.38, would still think they were paying too much for funds. However, they would also agree that the cost of debt financing was less than the cost of equity financing, since to them the value of the equity that would have to be surrendered is $5.91. Thus, while financiers and owners do not always agree on what the securities are worth, they may still be able to agree that debt reduces the differences in their valuations more than equity. As the example suggests, entrepreneurs will prefer debt to equity if the choice of instrument affects their perceptions of financing costs.

To establish the difference between debt and equity a little more formally, suppose both financiers and entrepreneurs believe the firm can generate one of two possible cash flows. Let the financiers’ estimates of these flows be yH and yL, while entrepreneurs’ are yH + a and yL + a, a > 0. To keep the symbolism to a minimum, suppose that financiers and entrepreneurs both believe either outcome can occur with equal probability. Financiers set the price of the instruments, but allow the entrepreneur to choose either the debt or the equity. In addition, suppose that if debt is used, financiers stipulate a repayment amount:

It will simplify the analysis to assume in addition that:

The second inequality in equation (24.1) implies that yH < 3yL, that is, for purposes of the present analysis the difference between high and low payoffs is limited.

Continuing to assume that financiers accept an interest rate of zero, financiers value the debt instrument at (yL + R)/2. Financiers are also willing to provide equity financing, as long as the proportion of the equity they can obtain has a current market value equal to that of the debt with promised repayment R. In order to have the same value as the debt, the proportion of equity issued, α, must satisfy:

(yL + R)/2 = α(yL + yH)/2

Solving the last equation for α gives:

Using equation (24.1), equation (24.2) implies:

so that α > 1/2. Then for any repayment R < yH the borrower's valuation of the debt is less than the borrower's valuation of the equity, as shown by:

Since financiers will advance the same amount of funds whether debt or equity is offered, the borrower will prefer to use debt, since from the borrower's point of view it lowers financing costs. The argument can be generalized to more outcomes, different probabilities, and more complex differences in the payoff distribution, but for present purposes the simple assumptions used above are sufficient to illustrate the point.

While in the last example the client is assumed to have more information than the financier, the opposite can sometimes be true. Axelson (2007) studies security design when investors rather than managers have private information about the firm, and argues that in such cases it can be optimal to issue equity. A “folklore proposition of debt” from traditional signaling models says that the firm should issue the least information-sensitive security possible, that is, standard debt. However, Axelson finds this proposition to be valid only if the firm can vary the face value of the debt as investor demand varies. If a firm has several assets, debt backed by a pool of the assets is more beneficial for the firm when the degree of competition among investors is low, but equity backed by individual assets is more beneficial when competition is high.

24.3 MORAL HAZARD9

Moral hazard, a classic consequence of informational asymmetries, frequently affects relations between a financier and an individual client.10 For example, if a financier does not take appropriate precautions, a firm seeking funds may use the proceeds of a debt issue to substitute a riskier project for the one originally proposed to the financier. The incentive to substitute a riskier project arises from the fact that, unless detected, shareholders of the firm would receive greater benefits from the substitution, while debt holders would bear greater risk. The following model of moral hazard analyzes a complete contract drawn up under conditions of risk.

24.3.1 Avoiding Moral Hazard

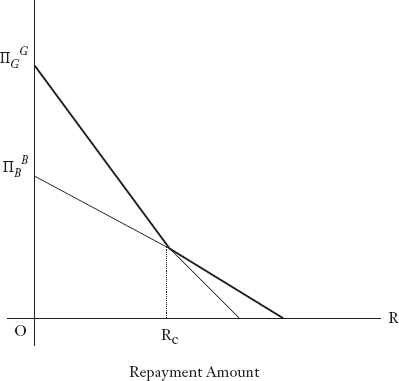

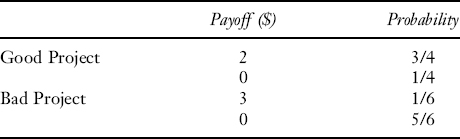

Consider a situation in which a borrower might substitute a bad project for a good one unless the lender takes steps to prevent it. Suppose that without any preventive measures the lender who advances the single unit of capital needed to implement a project has no further control over the type of project actually chosen. Suppose there is a good project that pays off either G with probability pG; or zero with probability (1 − pG). There is also a bad project that pays off B with probability pB or zero with probability (1 − pB). Suppose in addition that pG > 1 > pB, so that the good project has the higher expected value. Assume also that the interest rate is zero, the expected present value of the good project positive, and that of the bad project negative. Suppose finally that B > G, so that the owners of the firm could benefit from adopting the riskier project. The foregoing assumptions imply pG > pB, but depending on the size of the repayment, the owners of the firm may find themselves better off by choosing the bad project. They may be able to reap large rewards if the bad project succeeds, and it will be the financiers who suffer if it does not succeed.

The owners of the firm only face an incentive to choose the good project if they will be better off doing so after taking the size of the loan repayment into account. That is, the firm will choose the good project if:

pG(G − R) > pB(B − R)

This last, incentive, condition defines a critical value RC for the amount of repayment:

R > RC ≡ [pGG − pBB)

FIGURE 24.1 INCENTIVES FOR PROJECT CHOICE VERSUS SIZE OF REPAYMENT

Note: O- RC: region in which borrower has an incentive to choose the good project.

Note that since G < B, the last line also implies that RC < G: The financier cannot demand too high a repayment (i.e., too high an effective interest rate) without creating the possibility that the firm will substitute the bad project for the good one. Figure 24.1 indicates the situation from the firm's point of view. Of course, the repayment that the lender can charge must also be high enough for the lender to profit in an expected value sense. If not, the lender will decline the financing application.11

24.3.2 Incentives to Repay

Some financiers recognize that gradual revelation of information can be used to their advantage. For example, moral hazard problems can be mitigated if firms with good repayment records can obtain additional funds at lower cost. John and Nachman (1985) show that when a firm has to return repeatedly to the market for financing, it will benefit from considering the effects of its repayment choices on both current and future securities prices.

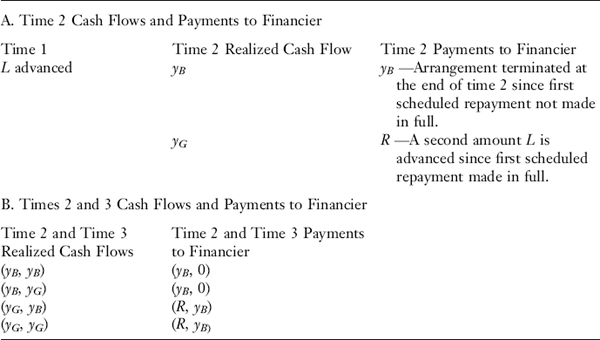

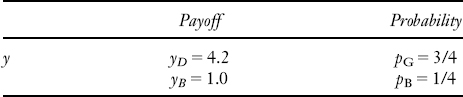

If the contingencies can be defined in advance, they can be incorporated in the original, complete contract. To illustrate, suppose that firms and financiers are both risk neutral, that the interest rate is zero, and that firms have no initial resources. In each period a firm adopting an investment project will generate a random income y, and the possible realizations of y are respectively yG and yB. If a lender cannot observe the cash flow, the most it will lend in an unsecured single period arrangement is yB. If it were to lend more, the borrower could claim he had only earned yB, and consequently repay only that amount.

Now consider a contract the lender agrees to renew for a second period whenever the borrower makes a payment of more than yB at the end of the first. However, if only yB is paid at the end of the first period, the arrangement will be terminated immediately. Assuming there are only two periods, the firm has no incentive to maintain a good reputation after time 2 has passed. Thus, if it has the cash flow to do so, the firm will make a payment larger than yB at time 2, but not at time 3. The arrangement is detailed in the two parts of Table 24.3.

The lender's expected profit from this arrangement is:

as may be determined from Table 24.3. Equation (24.5) can be rewritten as:

The lender will profit if R is large enough to ensure that π ≥ 0. The entrepreneur will enter the arrangement if R is small enough that she makes a profit when things turn out well for the firm at time 2; that is, if

which is equivalent to:

Any repayment that satisfies both the lender's profit condition and the borrower's incentive conditions will constitute a viable arrangement.

24.3.3 Collateral as a Screening Device

Contracts providing for collateral can be used as screening devices to mitigate the effects of informational asymmetries. Suppose loan contracts take the form (Ck, Rk) where Ck is the amount of collateral required, Rk is the corresponding repayment, and k is the type of firm entering the contract, k ∊ {G, B}. The symbols G and B refer to firms with good and bad quality projects, respectively. The good project pays off y with a relatively high success probability pG, or 0 with probability 1 − pG. The riskier, bad project B pays off y with a relatively low success probability pB or 0 with probability 1 − pB. The risk of the project is defined by its success probability, and borrowers know which type of project they have.

In all except the first instance examined below, lenders do not know which type of project the borrower has selected. All the bargaining power, that is, the power to set terms, is assumed to reside with the lender. The amount the borrower will be required to repay depends on the amount of collateral taken: Rk = Rk(Ck). If the project succeeds, then the realized cash flow is y, the lender is repaid Rk, and the borrower keeps y − Rk. If the project fails, then the realized cash flow is zero, the borrower loses the posted collateral Ck, and the financier realizes δ Ck,0 < δ < 1.

If the lender could observe the success probability pk, she would set the repayment amount and collateral so that the borrower's remaining income would just be:

where πk, min is the minimum amount the borrower must earn in order to undertake the project. Assume that the repayment amount is enough to make the deal attractive to the lender as well. If the lender could not observe pk, the best she could do is to earn an average profit dependent on the proportion of good and bad borrowers who might apply. The proportion will depend on the repayment required. If the repayment amount were sufficiently high, only the bad borrowers would find it worthwhile to apply for financing.

Lender profits can be improved by setting up a contract that will both induce good borrowers to post collateral and induce bad borrowers not to misrepresent themselves as good borrowers. In order for a contract to provide the correct incentives, it must specify repayments RG, RB, and collateral CG, such that it pays type B (high-risk) borrowers to declare themselves honestly as high risk:

At the same time the terms must be such that type G borrowers find it worth their while to declare themselves low risk and post the collateral to back up their declaration:

Inequality (24.11) indicates that the amounts realized by a borrower must exceed her opportunity cost πG, min. The repayment RG required of borrowers declaring themselves to be of good quality will be less than the repayment RB, which means the low-risk borrowers pay a lower effective interest rate. In essence, low-risk borrowers bet they will not fail, post collateral to indicate their confidence, and thereby qualify for a lower interest rate than that paid by high-risk borrowers. High-risk borrowers do not take the same arrangement because to do so they would have to post collateral that, according to their private information, they have a high probability of losing.

24.4 COMPLETE CONTRACTS

Qian and Strahan (2007) find that in countries with strong creditor protection, bank loans have more concentrated ownership, longer maturities, and lower interest rates. The authors argue that more credit can be extended and on more generous terms when lenders have more credible threats in the event of default. Similar research shows a wide variety in choices of loan terms, but a complete discussion of variations is beyond the scope of this survey. Instead, this section illustrates two elementary choices based on complete contracts. The succeeding companion section provides similar illustrations for incomplete contracts.

24.4.1 Costly Verification

There is a body of literature based on costly verification where the design of an optimal contract between firms seeking external funds and financiers is assessed assuming that the profitability of a firm is private information. Although private, the information can be made public at a cost.

Suppose financiers cannot directly observe the firm's cash flow. As a result, financiers must either accept the realized cash flow value as reported by the firm, or conduct a costly audit. It will be worthwhile for financiers to conduct the audit if that costs less than the benefits expected to be gained from the verification. For example, suppose the borrower could report a cash flow yR, even though she actually realized y > yR. The financier could detect a propensity to report falsely by stipulating a repayment function and by designing an audit rule. If the firm's cash flow report is audited, the financier incurs a fixed cost γ; otherwise auditing costs are zero.

Clearly, an audit rule cannot be efficient unless it minimizes expected audit costs. A first requirement for managing audit costs is to conduct an audit only if repayment is not made in full. A second requirement is to minimize expected auditing costs by writing the contract for a fixed repayment, and setting the repayment size so as to minimize the probability of having to conduct an audit. If both parties are risk neutral, such a debt contract will be both incentive compatible and efficient so long as the firm is required to pay all reportedly available cash flows whenever the announcement is less than the full amount of scheduled debt repayment.12

24.4.2 Incentives to Report Honestly

Financiers can also try to design incentives for the borrower to report cash flows honestly. Suppose the borrower can be penalized for false reporting, using the penalty function:

where y is the actual cash flow, γ R the reported cash flow, and γ the proportional cost the borrower incurs if she does not report truthfully.13 If 0 < γ < 1, the borrower receives the realized cash flow, less the repayment (based on the reported cash flow) and less any penalty for not reporting truthfully:

The function R(yR) represents the repayment to the lender. This mechanism is falsification proof if it is maximized at yR = y, a situation that will occur if and only if:

That is, the borrower faces an incentive to report truthfully if the amount by which repayment increases in y is less than the amount by which the penalty increases in y.

By limited liability, R(0) = 0, which along with equation (24.14) means:

In turn, equation (24.15) means the lender cannot expect to be repaid more than γE(y). Then if L is the original amount lent and r the interest rate, the lender must also ensure that:

(1 + r)L ≤ γE(y)

If the borrower is risk averse and the lender risk neutral, the optimal form of repayment is a call option14 on the cash flow:

R(y) = max(0, γy − α)

where α is some positive constant. This contract provides incentives for truthful reporting and can be shown to minimize the probability that it will be necessary to audit the firm if the financier is to receive the expected value of the contract. For example, an audit will only be conducted if γR ≤ α/γ; that is, if the borrower does not make the loan payment in full and the financier assumes control of the firm. If y > α/γ, it is in the borrower's interest to make the scheduled repayment, since that maximize the amount of the proceeds he can retain.

24.5 INCOMPLETE CONTRACTS: INTRODUCTION

Diamond (2004) stresses that lenders can face difficulties in legal systems with ineffective enforcement, but if lenders do not attempt to collect from defaulting borrowers, the borrowers have greater incentives to default. Diamond argues that bank lenders would be more prone to enforce penalties if news about defaulting borrowers were to cause bank runs. In other words, tough collection schemes can help banks to retain depositor confidence.

In this section we provide models of such schemes. It first shows how renegotiation can improve bondholder payoffs when cash flows are unverifiable, and how an incomplete contract can overcome what would otherwise be market failure. Another form of incomplete contract allows a bank to renegotiate a deal and extract a greater expected profit from it than could bondholders without the same freedom to renegotiate.

24.5.1 Bondholder Threat to Liquidate

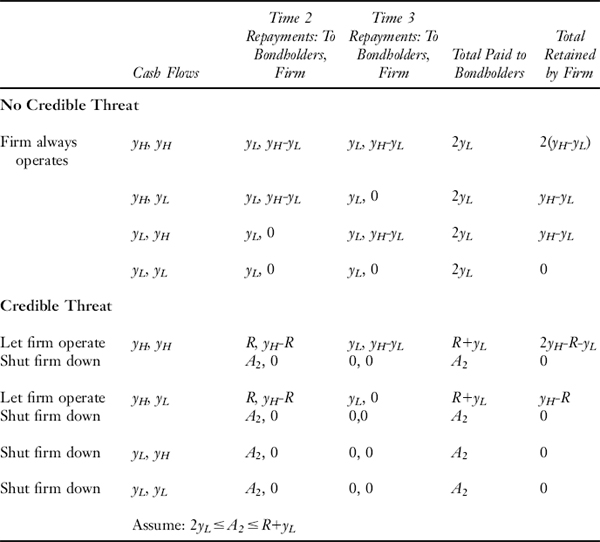

A credible threat can improve bondholders’ expected payoffs if they were to receive less than a scheduled repayment. The threat may even be effective enough to make viable an otherwise unviable transaction. Assume both the firm and bondholders are risk neutral, and that the interest rate is zero. The firm seeks one unit of money at time 1 in order to finance a project that generates cash flows at both times 2 and 3. At both time 2 and time 3 there are two possible cash flow realizations: yH with probability p or yL with probability (1 − p); yH > yL. Thus, the four possible cash flow patterns over two periods are (H, H), (H, L), (L, H), and (L, L), and they occur with probabilities p2, p (1 − p), (1 − p)p and (1 − p)2, respectively.

The firm operates for two periods unless bondholders shut it down early. The two-period profile of cash flows is assumed to be completely determined at time 1, but the realized values of the flows are assumed not to be verifiable by either party, or even by both parties acting together. Therefore, no lender can write a complete contract contingent on the realized cash flow.15

Since interest rates are zero, the present (and the future) value of the firm equals the sum of the realized cash flows in the two periods, less the scheduled loan repayments. The realized cash flow at time 3 is zero if the firm is put out of business, and either yH or yL if the firm is allowed to continue operating in the second period. Bondholders can shut down operations after time 2 if they do not receive the full amount of the time 2 scheduled repayment. However, if they do receive the time 2 repayment in full, bondholders permit the firm to continue operating until time 3.

In the event of liquidation the bondholders receive the larger of the cash flow yL or the time 2 liquidation value A2. The time 3 liquidation value is assumed to be A3 = 0, so that the maximal amount a lender can realize at time 3 is just yL. Since the bondholders cannot verify the firm's cash flow, the firm would never repay yH at time 2. If A1 < yL, a liquidation threat is not credible, since the firm cannot be forced to repay more than yL. In this case, the bondholders can never expect repayment of more than 2yL. Since bondholders must advance 1 to finance the project, and since interest rates are assumed to be zero, the market will fail if 2yL < 1. The details are given in Table 24.4.

If A2 > yL, the liquidation threat is credible. Assuming that bondholders have no powers to renegotiate existing arrangements, they will shut down the firm if a scheduled time 1 payment is not made in full. In what follows we shall assume that the liquidation value is A2, such that 2yL < A2 < yL +R. A firm that is shut down at time 1 cannot earn any income at time 2. Therefore, a firm that knows its cash flows will be (H, H) (remember they learn this at time 2) will want to continue operating, and will therefore make the time 2 scheduled repayment. A firm knowing its cash flows to be (H, L) will not default. If the firm were to default, it would get nothing whereas if it pays R the firm gets to keep yH − R from the first period, but nothing from the second period. When the firm cannot offer more than yL at time 1, the bondholders will shut it down and keep A2.

TABLE 24.4 CASH FLOWS AND THEIR DISTRIBUTION

The ability to threaten closure means that from the lender's point of view the financing will be viable whenever

The condition in equation (24.16) can be satisfied for sufficiently large values of both R and A2 even if 2yL < 1, creating the possibility of market failure in the absence of a credible threat. For example, if yL = 1/6 and A2 > 2/6, then any value of R > A2 − 1/6 will satisfy condition (24.16). Thus, the threat to liquidate can sometimes make market financing viable even if inability to invoke a credible threat would imply market failure.

24.5.2 Renegotiating a Bank Loan

Gorton and Kahn (2000) model how a bank might renegotiate with a borrower.16 Essentially, depending on how the borrower's business evolves, the bank stipulates a right to renegotiate the loan contract, thus permitting it to contemplate a variety of outcomes ranging from full repayment, through extension, to completely forgiving the loan. In the following model, the bank will renegotiate rather than liquidate, if the net present value of its loan repayments can be increased through restructured financing.17

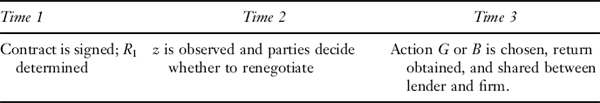

The model has three times: 1, 2, and 3. The firm is assumed to borrow 1 at time 1, and agrees to repay R1 at time 3. At time 2, both the borrower and the bank observe a (nonverifiable) signal z.18 At that time a bank with a credible threat to liquidate can force renegotiation, thereby providing the firm with the incentive to choose a good investment project at time 3, and thus improve the prospects of both firm and bank. The timing is shown in Table 24.5.

TABLE 24.5 TIMING OF CONTRACT, RENEGOTIATION DECISION, AND PAYOFFS

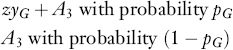

The firm can choose between two investment projects. Project G has the returns distribution:

Project B has the returns distribution:

The assumptions pGyG > pByB and yG < yB present the moral hazard problems discussed in Chapter 7. If lenders are to avoid the consequences of moral hazard, they must stipulate a repayment R1, such that:

Note that R1 cannot be made too large without violating the condition in equation (24.17). As described earlier in this chapter, when we covered costly verification (Section 24.4.1), management must be motivated to choose the good project rather than the bad one. If the project fails, management gets nothing since the model assumes R1 > A3, meaning that financiers claim the entire amount A3.

The condition in equation (24.17) can be satisfied if z is known at the time of setting R1. However, in the assumed circumstances, z is not known when R1 is set, and if the realized value of z is small enough, then at time 1, the condition in equation (24.17) will turn out to be violated for the given value of R1. That is, for any given value of R1 there is a critical value of z* = z*(R1), such that if z, z* management has an incentive to adopt the bad project. Given R1, z* is defined as the value of z that makes the condition in equation (24.17) an equality.

If the realized value of z is such that z < z*, there is a potential for the bank to mitigate moral hazard by renegotiating the contract. Let the project have liquidation values A2 and A3 at times 2 and 3, respectively; A2 > A3.

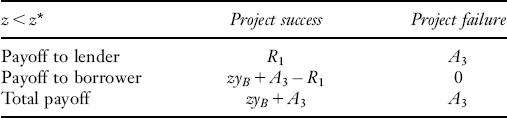

Suppose the possible realizations of z have a minimum value z0 and suppose pBz0yB ≥ R1. A3 so that if the firm is allowed to continue until time 2 the lender will be repaid in full if the project succeeds, but not if it fails. The payments to both parties are illustrated for the case z < z* in Table 24.6.

Suppose it is time 2 and the bank has no credible threat. In this case the lender cannot renegotiate, and her expected return is:

TABLE 24.6 Z < Z*, BUT FIRM CONTINUES UNTIL TIME 3

The value of renegotiation lies in its potential to increase the lender's payoff, but in order for the bank to be able to force renegotiation, it must have a credible threat.19 There is no credible threat if z > z*, but if z < z*, the threat is credible if also

Consider what would happen if equation (24.19) were satisfied. The bank's problem is to decide whether to liquidate early or to reset R1 to a smaller value R2 and allow the firm to continue in business. However, R2 cannot be too large without again incurring moral hazard. The optimal decision is defined to be one that maximizes the bank's expected return,20 taking account of the moral hazard possibility.

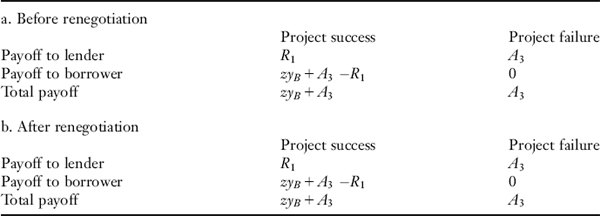

Continue to assume equation (24.19) and suppose the bank has all the negotiating power. Under these assumptions the bank can alter the repayment terms as it sees fit. The bank will liquidate the firm if that offers a higher expected value than other alternatives. However, if continuation has the higher expected value, the bank can maximize its return by providing the borrower with an incentive to pick the better project. Suppose there is some value R2 < R1, such that:

Suppose, for a given value of z, that R2 = R2(z) satisfies both equations (24.17) and (24.20). Then the bank will choose renegotiation rather than liquidation, because that increases the expected return of both the bank and the firm. For instance, if the bank sets:

then equation (24.17) holds and the firm is motivated to choose the better project. The payoffs to both parties are shown in the two parts of Table 24.7.

TABLE 24.7 Z < Z* BEFORE AND AFTER RENEGOTIATION

The bank will profit from the renegotiation if:

24.6 INCOMPLETE CONTRACTS: FURTHER COMMENTS

In this section we further examine deals under uncertainty. In contrast to the previous section where cash flows were known but not verifiable, we now consider deals in which it is not possible to establish cash flow magnitudes using a probability distribution that is sufficiently precise to be useful. In some cases, parties to the deal are aware that even though they cannot specify future contingencies exactly, the contingencies can still affect the deal's payoffs (see Hart, 2001, p. 1,083). To complete such deals, financiers write contracts providing for adjustments to be made according to guidelines based on certain principles.

24.6.1 Uncertainty and Governance

A deal's payoff uncertainty can arise from a variety of sources, including fund seeker's actions, third-party actions, or changes in the economic environment. The different possible sources of uncertainty can affect financier responses. As one example, financiers may try to negotiate with different parties to absorb possible adverse impacts. In natural gas pipeline construction, financiers may request their clients to obtain an advance ruling from the regulatory authorities, permitting the pipeline company to pass on any construction cost increases to consumers by increasing the cost of gas. The advance ruling has the effect of reducing the uncertainty that the project will be able to turn a profit large enough to repay the financiers.

Financiers may interpret management actions as signals indicating the possible gravity of different uncertainties. For example, management's willingness to join an endeavor likely evinces belief in the project's success, particularly if management personnel invest in the project. Equally, of course, resignation of key personnel could be taken as indicating management's lack of faith in project prospects.

Rating agencies are unlikely to play prominent information production roles under uncertainty, since their main function is to refine estimates of risks at relatively low cost. For example, in the subprime meltdown of 2007 2008, it became clear that rating agencies had failed to assign appropriate ratings to complex mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and structured credit products (e.g., collateralized debt obligations, CDOs) until relatively late in the subprime lending boom. Although the rating agencies might not have faced uncertainty initially, they clearly did so after investors lost confidence in the complex investment products. After the loss of confidence, market prices for the instruments sometimes exhibited large discounts attributable at least as much to investor fears as to objective changes in the underlying security.

However, consultants or other experts—observers with specialized knowledge—may be able to determine key implications of a deal's uncertainties. For example, market research experts might offer clients estimates of a product's likely sales volumes under different economic circumstances. This information could in turn affect the phasing of a business's product offerings and ultimately its profitability.

24.6.2 Ex Post Adjustment

All contracts involve fund seeker-financier interdependence, but the degree of interdependence is greater with an incomplete contract. For an uncertain deal to reach a successful conclusion, financier and fund seeker depend on each other to reveal information and to cooperate more fully than with a complete contract. This interdependence is usually reflected in arrangements that provide for greater flexibility in governance as and when originally unforeseen events occur. For example, the arrangements may include using equity in place of debt in order to obtain voting rights on the board of directions of a corporation seeking funds rather than imposing contractual obligations such as maintaining a given working capital ratio.

Ex post adjustments can sometimes benefit both financier and fund-raising entity, as the preceding models of risky deals have indicated. Under uncertainty, ex post adjustments can be based on learning about the key profitability features of a deal and how to manage those features effectively. They may also allow the entity seeking funds to learn how to operate the firm more profitably, or to enhance the probability of its long-run survival.21 On the other hand, debt renegotiation subsequent to a default can be cumbersome and lengthy because it can mean obtaining agreement from a relatively large number of lenders who may not agree on the terms of the renegotiation.

A given set of terms does not necessarily offer net benefits in every possible outcome state; compare Hart (2001). A contract that does not provide for unforeseeable contingencies can be finely tuned to work perfectly under one set of circumstances, but can work badly if other circumstances are encountered. A more flexible contract that contains provisions for unforeseeable contingencies may not work perfectly under any set of circumstances, but there may be a considerable variety of different circumstances under which it works relatively well. The parties to a deal do not always recognize that their agreement constitutes an incomplete contract. Moreover, a failure of this type can weaken the financiers’ ability to profit from the deal. If and when the incompleteness is recognized, financiers will then try to devise adjustments, but they will be in a weaker position than if they had originally foreseen the need for adjustments.

The credit crunch of 2007–2008 offers numerous examples. For instance, banks found themselves forced, for reputational reasons, to take back the default risk on instruments they previously regarded as having been sold. As a second example, credit derivatives (more specifically, one form of credit derivative called a credit default swap) that were originally thought to be safe hedges came to be questioned as the issuing insurance companies’ capital dwindled and could not be replaced.

24.6.3 Bypassing Uncertainty

One obvious way of dealing with uncertainty is to pass its effects on to another party, say the client. For example, a few Japanese banks, concerned in the later 1980s about the possibility of eventual peaking in the then rapidly rising Japanese real estate prices, were able to securitize some of their property loans using equity instruments. This strategy passed the risk of capital loss on to the purchasers of the equities. Of course, since it also passed on any future capital gains, it may well have been that the sellers placed a lower expected value on possible capital gains than did the purchasers.

Collateral can also be used to bypass the effects of uncertainties, since financing can be secured by the market value of the collateral rather than by the firm's uncertain cash flows, as discussed earlier in this chapter. Still further, various forms of guarantees might also be used for the same purposes. For example, governments frequently provide export credit insurance to businesses engaged in foreign trade. Export credit insurance cannot always be obtained from the private sector, because it may involve insuring shipments against risks that neither the financier nor the client can control, such as losses from acts of war. As a second example, certain actions by management or the board of a corporation can be bonded to cover financiers against losses arising from fraud or malfeasance. As a third example, financings may be insured against such eventualities as death of key management personnel.

24.6.4 Research Findings

Davydenko and Strebulaev (2007) examine an aspect of uncertainty in asking whether the strategic actions of borrowers and lenders can affect corporate debt values. They find higher bond spreads for firms that have the capability to renegotiate debt contracts relatively easily: The firm's threat of strategic default depresses bond values ex ante. Moreover, the effect of strategic action is greater when lenders are vulnerable to threats, as might occur in the cases of relatively large proportions of managerial shareholding, simple debt structures, and high liquidation costs.

24.7 ISSUANCE OF MULTIPLE DEBT CLAIMS

In earlier chapters when we discussed financing, we described the capital structure in terms of debt and equity, where there was only one form of the latter. Yet, firms typically have a more complicated debt structure. Upon recognizing the effects of taxes and the costs of financial distress, the capital structure question becomes: Why should management have a debt structure rather than just one type of debt? That is, what is the economic rationale for partitioning the cash flows generated from among the firm's different debt instruments that have different risk attributes, and how to partition optimally the claims on the firm's asset. Boot and Thakor (1993) tackle this issue. They demonstrate when there is asymmetric information, proceeds raised in external financing are increased by partitioning the firm's cash flow because it makes informed trade of the securities more profitable.

Boot and Thakor formulate a model in which it is assumed that the value of a firm's cash flows is a priori unknown by investors but that value can be revealed by some investors at a cost. In their model there are three types of traders who bid on securities: (1) pure liquidity traders, (2) traders who become informed at a cost about the firm's intrinsic value (i.e., informed traders), and (3) uninformed discretionary traders who could become informed but choose to remain uninformed. The following is also assumed: (1) trading on information should be profitable, (2) the demand from informed traders should be endogenous, and (3) equilibrium prices embody at least some of the information of informed traders.

The Boot-Thakor analysis shows that management can maximize proceeds from an external financing by partitioning the firm's cash flows from assets in place by issuing different financial claims. Basically, this is done by creating two types of securities. The first is an informationally insensitive security designed to include just one debt claim on the cash flows. The second type is an informationally sensitive security designed to include more than one debt claim on the cash flows. Creating these two types of securities allows informed trading to be more profitable because informed traders have the potential to generate a higher return from the production of information by allocating their portfolio to the information-sensitive security. Trading by informed traders will push the more valuable security's equilibrium price closer to its fundamental value. This will then increase the proceeds received by the firm.

24.8 SECURITIZATION

Securitization is a form of external financing used by operating corporations who accumulate assets in the course of their business (e.g., receivables and lease receivables), as well as intermediaries such as banks that have assembled a portfolio of loans. The pool of assets is used as collateral for the offering of multiple securities with different priority claims on the cash flows of the asset pool. Securitization is an alternative funding source to using the same pool of assets for the issuance of a bond secured by those assets. In this section, we describe the securitization process and the incentive for those who have assembled a portfolio of assets to issue multiple securities against the portfolio's cash flow.

24.8.1 Basics of Securitization

To understand this, let's begin with a brief description of a securitization. With traditional forms of secured bonds, it is necessary for the issuer to generate sufficient earnings to repay the debt obligation. So, for example, if a manufacturer of farm equipment issues a bond in which the bondholders have a first mortgage lien on one of its plants, the ability of the manufacturer to generate cash flow from all of its operations is earmarked to pay off the bondholders. In contrast, in an asset securitization transaction, the burden of the source of repayment shifts from the issuer's cash flow to the cash flow generated by a pool of financial assets, potentially supplemented by a third-party guarantee of the payments should the asset pool not generate sufficient cash flow. For example, if the manufacturer of farm equipment has receivables from installment sales contracts to customers (i.e., a financial asset for the farm equipment company) and uses these receivables in a structured financing as described below, payment to the buyers of the bonds backed by the receivables depends on the ability to collect the receivables. It does not depend on the ability of the manufacturer of the farm equipment to generate cash flow from operations.

The process of creating securities backed by a pool of financial assets is referred to as asset securitization. The financial assets included in the collateral for an asset securitization are referred to as securitized assets.

24.8.2 Illustration of a Securitization

Let's use an illustration to describe an asset securitization transaction. In our illustration, we will use a hypothetical firm, Farm Equip Corporation. This company is assumed to manufacture farm equipment. Some of its sales are for cash, but the bulk of the sales takes the form of installment sales contracts. Effectively, an installment sale contract is a loan to the buyer of the farm equipment who agrees to repay Farm Equip Corporation over a specified period of time. For simplicity, we will assume that the loans are typically for four years. The collateral for the loan is the farm equipment purchased by the borrower. The loan specifies an interest rate that the buyer pays.

The credit department of Farm Equip Corporation makes the decision to extend credit to a customer. That is, the credit department will receive a credit application from a customer and, based on criteria established by the firm, will decide on whether to extend a loan and the amount. The criteria for extending credit or a loan are referred to as underwriting standards. Because Farm Equip Corporation is extending the loan, it is referred to as the originator of the loan. Moreover, Farm Equip Corporation may have a department that is responsible for servicing the loan. Servicing involves collecting payments from borrowers, notifying borrowers who may be delinquent and, when necessary, recovering and disposing of the collateral (i.e., farm equipment in our illustration) if the borrower does not make loan repayments by a specified time. While the servicer of the loans need not be the originator of the loans, in our illustration we are assuming that Farm Equip Corporation is the servicer.

Now let's get to how these loans can be used in a securitization transaction. We will assume that Farm Equip Corporation has more than $200 million of installment sales contracts. This amount is shown on the corporation's balance sheet as an asset. We will further assume that Farm Equip Corporation wants to raise $200 million. Rather than issuing corporate bonds management decides to raise the funds via a securitization.

To do so, the Farm Equip Corporation will set up a legal entity referred to as a special-purpose entity (SPE), also referred to as a special-purpose vehicle (SPV). The purpose of this legal entity is critical in a securitization transaction because it allows the separation of the assets from the originator and the SPV. In our illustration, the SPE that is set up is called FE Asset Trust (FEAT). Farm Equip Corporation will then sell to FEAT $200 million of the loans. Farm Equip Corporation will receive from FEAT $200 million in cash, the amount it wanted to raise. But where does FEAT get $200 million? It obtains those funds by selling securities that are backed by the $200 million of loans. The securities are called asset-backed securities. The asset-backed securities issued in a transaction securitization are also referred to as bond classes or tranches.

A simple transaction can involve the sale of just one bond class with a par value of $200 million. We will call this Bond Class A. Suppose that 200,000 certificates are issued for Bond Class A with a par value of $1,000 per certificate. Then, each certificate holder would be entitled to 1/200,000 of the payment from the collateral. Each payment made by the borrowers (i.e., the buyers of the farm equipment) consists of principal repayment and interest. A securitization transaction is typically more complicated.

An example of a more complicated transaction is one in which two bond classes are created, Bond Class A1 and Bond Class A2. The par value for Bond Class A1 is $90 million and for Bond Class A2 is $110 million. The priority rule can simply specify that Bond Class A1 receives all the principal that is paid by the borrowers (i.e., the buyers of the farm equipment) until all of Bond Class A1 has paid off its $90 million and then Bond Class A2 begins to receive principal. Bond Class A1 is thus a shorter-term bond than Bond Class A2. By creating securities with maturities that differ from the maturity of the underlying financial assets, particular investors’ needs can be satisfied. For example, if the collateral has a maturity of say five years, bond classes can be created with say, a one-year maturity, two-year maturity, and five-year maturity. This creation of bond classes with different maturities is called time tranching.

There are typically structures with more than one bond class, and the classes differ as to how they will share any losses resulting from defaults of the borrowers in the underlying collateral pool. In such a structure, the bonds are classified as senior bond classes and subordinate bond classes. The structure itself is referred to as a senior-subordinate structure. Losses are absorbed by the subordinate bond classes before any are realized by the senior bond classes. The senior bond classes have less credit risk than the subordinated classes. For example, suppose that FEAT issued $180 million par value of Bond Class A, the senior bond class, and $20 million par value of Bond Class B, the subordinate bond class. As long as there are no defaults by the borrower greater than $20 million, then Bond Class A will be repaid fully its $180 million.

The design of a senior-subordinate structure offers an example of redistributing the credit risk of the collateral to different bond classes. Investors seeking a security with high credit quality but who would be unwilling to purchase the individual financial assets in the collateral would be candidates to purchase the senior bond classes. Investors willing to accept greater credit risk would be candidates to purchase the subordinate bond classes. This is process of creating bond classes with different credit risk is referred to as credit tranching.

24.8.3 Securitization and Funding Costs

Although there are reasons other than cost why a corporation or a financial intermediary might issue securities via a securitization rather than issuing a bond backed by the portfolio of assets, we will confine our discussion to the issue of maximizing proceeds from the issuance of securities backed by the portfolio (i.e., optimal security design).22

The implication of the Boot-Thakor model for why a firm would be economically advantaged by creating the multiple debt securities that we described in the previous section is also capable of providing insights as to why the management of an operating corporation would be motivated to issue multiple classes of claims against portfolios of a pool of assets via the securitization process. In the securitization process, management of the firm seeking external funding can structure the transaction so as to create securities with different degrees of information sensitivity. According to the Boot-Thakor model, this can generate greater proceeds than issuing a secured corporate bond.

There are other explanations to explain the benefits from partitioning the cash flow of an asset pool. Gorton and Pennacchi (1990) find that an issuer can make informed investors interested in relatively information-insensitive securities better off by splitting the total asset cash flow from a pool of assets so as to create a liquid asset whose payoff does not embody private information.

DeMarzo (2005) offers another explanation as to how arbitrage profits can be garnered by tranching collateral. He determines the optimal strategy for an entity that owns a pool of assets when that entity has superior information about the value of the underlying assets. When faced with a choice of selling either individual assets or the entire asset pool, he shows that the entity is better off following the former strategy due to the information destruction effect of asset pooling. However, when the capital market allows the entity to issue multiple debt classes (or tranches) collateralized by the pool of assets, then it may be optimal to sell such a structure. Tranching gives the entity the opportunity to exploit the risk diversification effect if the residual risk of each asset in the pool is not highly correlated. This will result in some tranches within the financing structure that have a low risk and are highly liquid.

Brennan, Hein, and Poon (2009) present yet another explanation for creating a structured product with tranches that can potentially generate arbitrage profits. Although the arguments are in terms of CDOs, which employ the securitization technology, the argument applies in full force to asset-backed securities. They set forth a theory of the impact on initial market pricing (i.e., issuance spread) attributable to collateral diversification and tranching. The key assumption underlying their theory is that some investor groups do not have the capability to evaluate tranches from a structured product, and, as a result, investors that fall into this category are highly dependent on bond ratings. If this is the case and if the rating agencies assign a higher valuation for a tranche than the tranche's fundamental value, then tranches can be marketed and sold based solely on ratings. Brennan, Hein, and Poon then go on to describe the drawbacks of the rating systems employed by the major rating agencies because they rely on either default probabilities (Standard & Poor's and Fitch) or expected losses due to default (Moody's). They argue that both systems can be gamed by bankers in working with clients to generate arbitrage profits.

KEY POINTS

- Financial contracting attempts to explain the different kinds of deals made between financiers and their clients. In particular, financial contracting seeks to explain the economics of choosing a security design that can mitigate conflicts among the parties.

- The informational conditions under which a deal is arranged affect both the nature of the contract used and the governance mechanism employed to administer the contract. If deals are arranged under risks commonly understood by both parties, a complete contract is relatively easy to arrange. If risks are assessed asymmetrically, the complications of moral hazard and of adverse selection can arise.

- Deals arranged under uncertainty cannot be arranged using complete contracts. Rather, agreement over the principles under which the deal can be conducted is the most that can be determined in advance.

- Deals with differing attributes are usually arranged at different interest rates to compensate for the risk or uncertainty involved.

- The transactions costs of a deal include both the direct costs a client pays a financier and such indirect costs as the search costs involved in finding an accommodating financier.

- Screening costs are the ex ante costs a financier incurs to assess a funding proposal, while monitoring costs are the ex post costs involved in the deal's continuing governance.

- Financiers select governance mechanisms according to each deal's informational conditions. Risky deals may involve conditions of either informational symmetry or informational asymmetry.

- In the presence of informational asymmetry between financiers and their clients, debt may come closer than equity to resolving their differences.

- Moral hazard is a consequence of informational asymmetries. A financier may be able to manage the effects of moral hazard judiciously, albeit at increased governance costs.

- Even complete contracts arranged under risk can involve costly verification of outcomes.

- The difficulties presented by incomplete contracts can sometimes be mitigated by the use of renegotiation or liquidation schemes.

- Deals arranged under uncertainty create greater interdependence between financier and client, and the effects of interdependence can partially be mitigated by using relatively flexible governance arrangements.

- Firms may employ relatively complex financing structures in order to mitigate effects such as those due to differently distributed information.

- Securitization is a form of external financing used both by operating corporations that accumulate assets in the course of their business and by intermediaries that assemble and refinance portfolios of loans.

- In some cases, the costs of overcoming market imperfections can be reduced by using securitization.

QUESTIONS

- a. What is meant by financial contracting?

b. What is the objective of financial contracting?

- From the client's point of view, a deal's total transaction costs include both direct and indirect costs.

- What is meant by direct costs?

- What is meant by indirect costs?

- From the financer's point of view, what do a deal's costs include?

- The average cost of administering a deal is the sum of its screening and monitoring costs, along with the cost of making any adjustments that monitoring indicates would be desirable.

- What is meant by screening costs?

- What is meant by monitoring costs?

- Which of the following factors can lead to A lower average cost of administering a deal? Which ones would lead to A higher average cost?

- Larger transaction volume

- Greater informational difference between clients and financier

- Financiers having more experience with the deal

- Markets with impediments to arbitrage

- a. What is meant by an incomplete contract?

b. Under which informational conditions will deals be arranged using a complete contract?

c. Under which informational conditions will deals be arranged with an incomplete contract?

- Provide some reasons why informational asymmetries between financier and a firm are difficult to resolve in a private market and in intermediated transactions.

- Suppose the owners of a firm and financiers are risk neutral, and that interest rates are zero. Suppose also that the owners are optimistic, while financiers are pessimistic, and their views about the earnings distributions are shown in the following table. Suppose the firm needs to raise $5.5.

- What is the value of equity from the point view of owners?

- What is the value of equity from the point view of financiers?

- If the firm raises the needed $5.5 through equity, what proportion of the shares would the financiers demand? How much are those shares worth from the point view of owners?

- Alternatively, suppose financiers propose a debt issue that promises to pay off $5.75 if the firm has the funds, or whatever funds are available if the firm does not generate cash flows at least equal to $5.75. How much would the financiers value the debt?

- How much would the owners value the debt?

- Combining all the above results, which form of financing would the owners prefer to raise the needed $5.5, equity or debt? Why?

- Consider a firm that gets the single unit of capital needed to implement a project. Suppose that the owner might substitute a bad project for a good one unless the financier takes steps to prevent it. The payoff distributions of the good project and the bad project are shown in the following table.

- If the financier sets the loan payment as $2, what is the expected payoff to the owner after taking the size of the loan payment into account when selecting the good and bad project, respectively? Which project would the owner choose?

- Consider the situation when the financier sets the loan payment as $1.5. Answer the same questions raised in (a).

- What range should the financier set the loan payment so that the owner does not have an incentive to substitute the bad project for the good one?

- Suppose that firms and financiers are both risk neutral, that the interest rate is zero, and that firms have no initial resources. In each period a firm adopting an investment project will generate a random income y, and the distribution of y is shown in the following table.

Now consider a contract in which the lender advances $2 and agrees to renew for a second period whenever the borrower makes a payment of more than yB at the end of the first period. If only yB is paid at the end of the first period, the arrangement will be terminated immediately. Assuming there are only two periods, the firm has no incentive to maintain a good reputation after time 1 has passed.

What conditions should the loan repayment at time 1 satisfy so that the lender's expected profit is positive and the entrepreneur is willing to enter the arrangement?

- Explain briefly how collateral can be used as a screening device to mitigate the effects of informational asymmetries.

- Explain the benefit of ex post adjustments used in contracts for deals under uncertainty.

- Firms typically have a debt structure with more than just one type of debt. Boot and Thakor (1993) show that management can maximize the proceeds from an external financing by partitioning the firm's cash flows from assets in place by issuing different financial claims. Explain briefly how it works.

- a. What is meant by asset securitization?

b. What is meant by securitized assets?

REFERENCES

Arrow, Kenneth J. (1974). Essays on the Theory of Risk-Bearing. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Axelson, Ulf. (2007). “Security Design with Investor Private Information,” Journal of Finance 62: 2587–2632.

Brennan, Michael J., Julia Hein, and Ser-Huang Poon. (2009). “Tranching and Rating,” European Financial Management 15: 891–922.

Benson, Earl D. (1979). “The Search for Information by Underwriters and Its Impact on Municipal Interest Cost,” Journal of Finance 34: 871–885.

Boot, Arnoud, and Anjan V. Thakor. (1993). “Security Design,” Journal of Finance 48: 1349–1378.

Davydenko, Sergei A., and Ilya A. Strebulaev. (2007). “Strategic Actions and Credit Spreads,” Journal of Finance 62: 2633–2671.

DeMarzo, Peter. (2005). “The Pooling and Tranching of Securities: A Model of Informed Intermediation,” Review of Financial Studies 18: 1–35.

Diamond, Douglas W. (2004). “Committing to Commit: Short-Term Debt when Enforcement is Costly,” Journal of Finance 59: 1447–1479.

Fama, Eugene F. (1985). “What's Different about Banks?” Journal of Monetary Economics 15: 29–39.

Freixas, Xavier, and Jean-Charles Rochet. (1997). Microeconomics of Banking. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.