06

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:84

(RAY)

084-091_30056.indd 84 3/4/13 7:32 PM

Text

8 4

THE INTERIOR DESIGN REFERENCE + SPECIFICATION BOOK

Chapter 6: Sequencing Spaces

Although the art of composing a plan would seem to be the province of the archi-

tect, the interior designer must be involved in choreographing the sequence of

spaces, so that a project reects a single design approach. Acknowledging the nec-

essary collaboration between architects and interior designers, it is important to

understand the two primary vehicles for organizing the relationship between rooms:

the plan and the cross section.

Through-Room and Independent Circulation

Interior design typically begins with the plan. Fundamental to the logic of the plan is the

distinction between rooms that can serve as both places and as routes for through-

circulation—such as the living room, dining room, and kitchen—and rooms that, because

of issues of privacy, require a separate circulation space or network of spaces to access

them—such as bedrooms and bathrooms.

Servant Spaces

A third type of space comprises closets, storage rooms, pantries, replaces, and powder

rooms. Spaces of this category should be consolidated into systemic

create acoustical privacy between larger rooms and to generate a logic for the plumbing, ven-

tilation, and mechanical systems and overall structure of the house. When composing a plan,

it is useful to consider these consolidated smaller spaces as solid masses, in opposition to

the open spaces of major rooms. In the late 1950s, American architect Louis Kahn qualied

this as an opposition between “servant” and “served” spaces. In the 1980s, the consolidated

zones of servant spaces came to be called the

technique used in the nineteenth century at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris (from the French

pocher

Relationships between Rooms

Networks of rooms can be conceived by aggregating rooms, with the gap between each

room functioning as both a thick-wall poche zone and a threshold space. Rooms can also be

created by subdividing a space with thick-wall zones or chunks of poche, as the Farnsworth

House illustrates below.

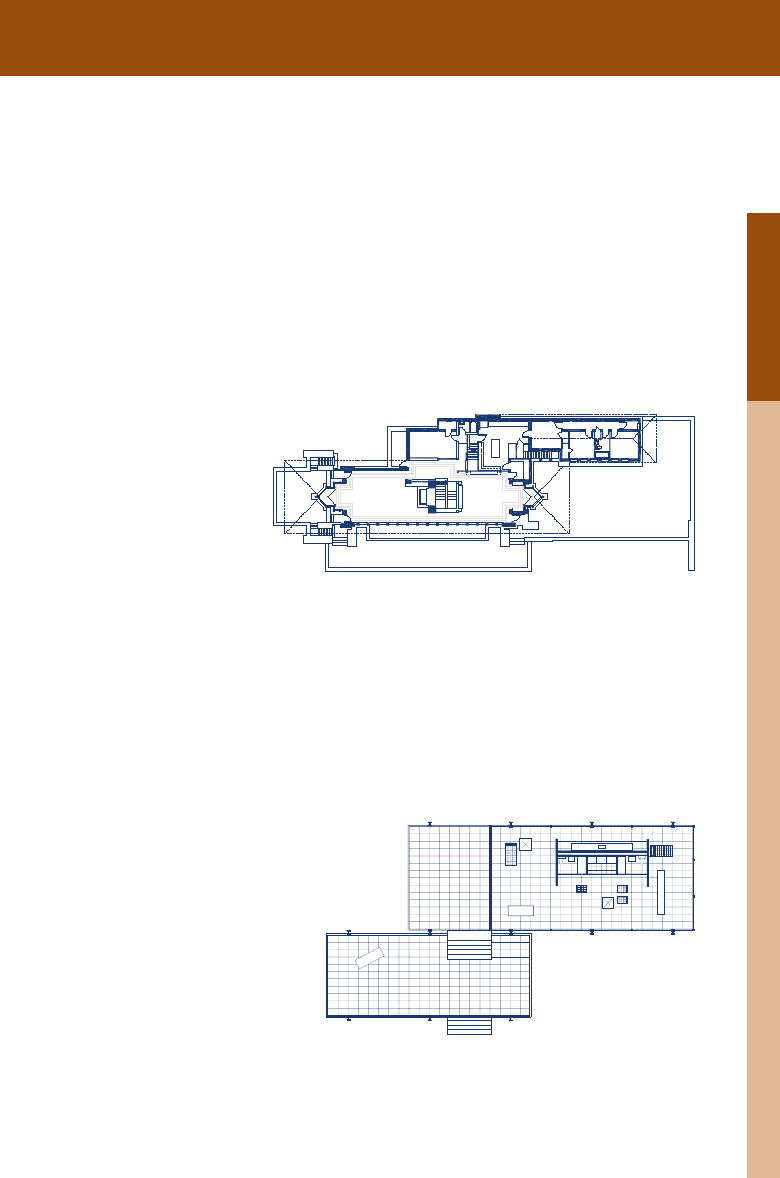

The plan of the Robie House is

composed of two distinct wings

that separate the public from

the private space.

The plan of the Farnsworth House

is a modern example of poche; the

kitchen, bathroom, and storage

areas are collected into one single

volume in the open plan.

section

plan

COMPOSING A HOUSE IN PLAN

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:84

(RAY)

084-091_30056.indd 84 3/4/13 7:32 PM

06

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:85

(RAY)

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:84

084-091_30056.indd 85 3/4/13 7:32 PM

Text

85

spaces, so that a project reects a single design approach. Acknowledging the nec

-

understand the two primary vehicles for organizing the relationship between rooms:

Servant Spaces

A third type of space comprises closets, storage rooms, pantries, replaces, and powder

rooms. Spaces of this category should be consolidated into systemic “thick-wall” zones to

create acoustical privacy between larger rooms and to generate a logic for the plumbing, ven-

tilation, and mechanical systems and overall structure of the house. When composing a plan,

it is useful to consider these consolidated smaller spaces as solid masses, in opposition to

the open spaces of major rooms. In the late 1950s, American architect Louis Kahn qualied

this as an opposition between “servant” and “served” spaces. In the 1980s, the consolidated

zones of servant spaces came to be called the “poche,” a term borrowed from a drawing

technique used in the nineteenth century at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris (from the French

pocher “to ll in”).

Frank Lloyd Wright, Robie House

Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House

Relationships between Rooms

Networks of rooms can be conceived by aggregating rooms, with the gap between each

room functioning as both a thick-wall poche zone and a threshold space. Rooms can also be

created by subdividing a space with thick-wall zones or chunks of poche, as the Farnsworth

House illustrates below.

The plan of the Robie House is

composed of two distinct wings

that separate the public from

the private space.

The plan of the Farnsworth House

is a modern example of poche; the

kitchen, bathroom, and storage

areas are collected into one single

volume in the open plan.

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:85

(RAY)

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:84

084-091_30056.indd 85 3/4/13 7:32 PM

06

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:86

(RAY)

084-091_30056.indd 86 3/4/13 7:32 PM

Text

8 6

THE INTERIOR DESIGN REFERENCE + SPECIFICATION BOOK

Attached or freestanding central

courtyard (California and the American

Southwest)

Plan Types in American Domestic Architecture

The differences among vernacular housing types, designed based on localized needs, con-

struction materials, and reflecting local traditions is the result of climatic variations (the

need to conserve heat versus the need to encourage cross ventilation), security concerns,

and the density of development. The American single-family house is generally organized into

five plan types.

Freestanding house organized around a

central fireplace core (the American North-

east and Midwest)

Freestanding house with a through-house

central stair hall with fireplaces on the end

walls (the American South)

Freestanding house with rooms orga-

nized along a south-facing double-story

portico (Charleston, South Carolina)

Attached row house with a stair and

corridor along one of the common

walls or in the middle of the plan sand-

wiched between exterior-facing rooms

(the American Northeast and Midwest)

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:86

(RAY)

084-091_30056.indd 86 3/4/13 7:32 PM

06

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:87

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:86

(RAY)

084-091_30056.indd 87 3/4/13 7:32 PM

Text

87

Sequencing Spaces

Attached or freestanding central

courtyard (California and the American

Southwest)

and the density of development. The American single-family house is generally organized into

Freestanding house with rooms orga-

nized along a south-facing double-story

portico (Charleston, South Carolina)

Attached row house with a stair and

corridor along one of the common

walls or in the middle of the plan sand-

wiched between exterior-facing rooms

(the American Northeast and Midwest)

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:87

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:86

(RAY)

084-091_30056.indd 87 3/4/13 7:32 PM

06

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:88

(RAY)

084-091_30056.indd 88 3/4/13 7:32 PM

Text

8 8

THE INTERIOR DESIGN REFERENCE + SPECIFICATION BOOK

COMPOSING A HOUSE IN SECTION

If a house is conceived as a series of independent oor levels, then every room on each oor

will share the same ceiling height. Ideally, however, a house should have rooms whose ceil-

ing heights differ in proportion to the overall size of each space. The height of the living room

should be greater than that of the powder room or a coat closet, for example. Opportunities for

such a house of interlocking rooms with different ceiling heights are best explored in section.

The simplest way to organize a mixture of ceiling heights is to make one or several rooms

double-height spaces, with the potential that rooms on the second level can look onto these

taller spaces. Le Corbusier organized houses around double-height living rooms at every stage

of his long career: The Villa Schwab of 1916 and the units in the Unité d’Habitation of 1949

are but two such housing designs.

Another strategy for varying spatial heights in a house is to connect one-and-a-half-story

rooms to adjacent one-story rooms via short stairs. Separating sections of the house by par-

tial-level stairs rather than the full-oor stairs of conventional house designs offers numerous

psychological and functional advantages.

As a variation on this strategy, in the 1920s Adolf Loos designed a series of houses that

organize the rooms of the main living level with a common ceiling plane, but allow the oor

levels to shift, creating rooms with a mix of ceiling heights. As a result, the interiors of Loos’s

houses resemble a terraced landscape. In houses with these complex sectional relationships,

the interconnecting stair needs to be carefully designed to take full advantage of views into

taller spaces and beyond to the exterior.

Le Corbusier, Villa Baizeau

COMPOSING AN OFFICE SPACE IN PLAN

Since the modern ofce is designed for a preexisting at-oor-plate ofce building, there are

very few opportunities for creativity in the section. Rather,

generates design possibilities

(1.5

the exterior window wall. This module works with the dimensional module of the American

systems furniture industry, including manufacturers such as Steelcase and Herman Miller.

This

occasionally wider for senior executives. It also governs other rooms located along the perim-

eter walls, such as conference rooms and reception areas.

A series of intimate, terraced spaces along

the sides of a triple-height space, exempli-

ed in the section of the Müller House, is

another strategy for varying spatial heights.

The section of the Villa Baizeau has interlocking

double-height spaces that become single-height

spaces when joined.

Job:02-30056 Title: RP-Interior Design Reference and Specification

#175 Dtp:216 Page:88

(RAY)

084-091_30056.indd 88 3/4/13 7:32 PM

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.