CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Identify and differentiate between the two broad approaches to ratemaking

- Explain the purpose of underwriting and describe the steps in the underwriting process

- Identify the principal sources of information on which an underwriter may rely

- Identify and differentiate among the various types of adjusters

- Identify and explain the steps in the loss adjustment process

As a part of our study of the insurance mechanism and the way it works, it will be helpful to examine some of the unique facets of insurance company operations. The unique nature of the insurance product requires certain specialized functions that do not exist in other businesses. In addition, financial record keeping of insurers deviates from common practices. In this chapter, we will examine some of the specialized activities of insurance companies, and in the next we will look at the financial aspects of their operations.

![]()

FUNCTIONS OF INSURERS

![]()

Although there are definite operational differences between life insurance companies and property and liability insurers, the major activities of all insurers may be classified as follows:

- Ratemaking

- Production

- Underwriting

- Loss adjustment

- Investment

In addition to these, there are other activities common to most business firms such as accounting, human resource management, and market research.

![]()

RATEMAKING

![]()

An insurance rate is the price per unit of insurance. Like any other price, it is a function of the cost of production. However, in insurance, unlike in other industries, the cost of production is unknown when the contract is sold, and it will remain unknown until some time in the future when the policy has expired. One fundamental difference between insurance pricing and the pricing function in other industries is that the price for insurance must be based on a prediction. The process of predicting future losses and future expenses and allocating these costs among the various classes of insureds is called ratemaking.

A second important difference between the pricing of insurance and pricing in other industries arises from insurance rates being subject to government regulation. As we noted in the preceding chapter, nearly all states impose statutory restraints on insurance rates. State laws require that insurance rates must not be excessive, must be adequate, and may not be unfairly discriminatory. Depending on the manner in which the state laws are administered, they impose differing limits on an insurer's freedom to price its products.

The ratemaking function in a life insurance company is performed by the actuarial department or in smaller companies, by an actuarial consulting firm.1 In the property and liability field, advisory organizations accumulate loss statistics and compute loss costs for use by insurers in computing final rates, although some large insurers maintain their own loss statistics. In the field of marine insurance and inland marine insurance, rates are often made by the underwriter on a judgment basis.

In addition to the statutory requirements that rates must be adequate, not excessive, and not unfairly discriminatory, other characteristics are considered desirable. To the extent possible, for example, rates should be relatively stable over time, so the public is not subjected to wide variations in cost from year to year. At the same time, rates should be sufficiently responsive to changing conditions to avoid inadequacies in the event of deteriorating loss experience. Finally, whenever possible, the rate should provide some incentive for the insured to prevent loss.

![]()

Some Basic Concepts

A rate is the price charged for each unit of protection or exposure and should be distinguished from a premium, which is determined by multiplying the rate by the number of units of protection purchased. The unit of protection to which a rate applies differs for the various lines of insurance. In life insurance, for example, rates are computed for each $1000 in protection; in fire insurance, the rate applies to each $100 of coverage. In workers compensation, the rate is applied to each $100 of the insured's payroll.

Regardless of the type of insurance, the premium income of the insurer must be sufficient to cover losses and expenses. To obtain this premium income, the insurer must predict the claims and expenses and then allocate these anticipated costs among the various classes of policyholders. The final premium the insured pays is called the gross premium and is based on a gross rate. The gross rate is composed of two parts, one that provides for the payment of losses and a second, called a loading, that covers the expenses of operation. That part of the rate intended to cover losses is called the pure premium when expressed in dollars and cents, and the expected loss ratio when expressed as a percentage.

Although some differences exist among different lines of insurance, in general, the pure premium is determined by dividing expected losses by the number of exposure units. For example, if 100,000 automobiles generate $30 million in losses, the pure premium is $300:

![]()

The process of converting the pure premium into a gross rate requires adding the loading, which is intended to cover the expenses required in the production and servicing of the insurance. The determination of these expenses is primarily a matter of cost accounting. The various classes of expenses for which provision must be made normally include the following:

- Commissions

- Other acquisition expenses

- General administrative expenses

- Premium taxes

- Allowance for contingencies and profit

In converting the pure premium into a gross rate, expenses are usually treated as a percentage of the final rate, on the assumption that they will increase proportionately with premiums. Since several of the expenses do vary with premiums (e.g., commissions and premium taxes), the assumption is reasonably realistic.

The final gross rate is derived by dividing the pure premium by a permissible loss ratio. The permissible loss ratio is the percentage of the premium (and so the rate) available to pay losses after provision for expenses. The conversion is made by the following formula:

![]()

Using the $300 pure premium computed in our previous example, and assuming an expense ratio of 0.40, we obtain

![]()

Although the pure premium varies with the loss experience for the particular line of insurance, the expense ratio varies from one line to another, depending on the commissions and the other expenses involved.

![]()

Types of Rates

The approach to setting rates is similar in most instances, but it is possible to distinguish between two different types of rates: class and individual.

Class Rates The term class rating refers to the practice of computing a price per unit of insurance that applies to all applicants possessing a given set of characteristics. For example, a class rate might apply to all types of dwellings of a given kind of construction in a specific city. Rates that apply to all individuals of a given age and sex are examples of class rates.

The obvious advantage of the class rating system is that it permits the insurer to apply a single rate to a large number of insureds, simplifying the process of determining their premiums. In establishing the classes to which class rates apply, the ratemaker must compromise between a large class, which will include a greater number of exposures and increase the credibility of predictions, and one sufficiently narrow to permit homogeneity. For example, a rate class could be established for all drivers, with one rate applicable regardless of the age, sex, or marital status of the driver or the use of the automobile. However, such a class would include exposures with widely varying loss potential. For this reason, numerous classes are established, with different rates for drivers based on factors such as those listed. Class rating is the most common approach today and is used in life insurance and most property and liability fields.

Individual Rates In some instances the characteristics of the units to be insured vary so widely that it is deemed desirable to depart from the class approach and calculate rates on a basis that attempts to measure more precisely the loss-producing characteristics of the individual. There are four basic individual rating approaches: judgment rating, schedule rating, experience rating, and retrospective rating.

Judgment Rating In some lines of insurance, the rate is determined for each individual risk on a judgment basis. Here the processes of underwriting and rate-making merge, and the underwriter decides whether the exposure is to be accepted and at what rate. Judgment rating is used when credible statistics are lacking or when the exposure units are so varied that constructing a class is impossible. This technique is most frequently applied in the ocean marine field although it is used in other lines of insurance.

Schedule Rating Schedule rating, as its name implies, makes rates by applying a schedule of charges and credits to some base rate to determine the appropriate rate for an individual exposure unit. In commercial fire insurance, for example, the rates for many buildings are determined by adding debits and subtracting credits from a base rate, which represents a standard building. The debits and credits represent those features of the particular building's construction, occupancy, fire protection, and neighborhood that deviate from this standard. Through the application of these debits and credits, the physical characteristics of each schedule-rated building determine that building's rate.2

Experience Rating In experience rating, the insured's own past loss experience enters into the determination of the final premium. Experience rating is superimposed on a class rating system and adjusts the insureds' premium upward or downward, depending on the extent to which their experience has deviated from the average experience of the class. It is most frequently used in the fields of workers compensation, general liability, and group life and health insurance. Generally, experience rating is used only when the insured generates a premium large enough to be considered statistically credible.3

Although the exact method of adjusting the premium to reflect experience varies with the type of insurance, the general approach is usually the same. The insured's losses during the experience period are compared with the expected losses for the class; the indicated percentage difference, modified by a credibility factor, becomes a debit or credit to the class-rated premium. The experience period is usually three years, and the insured's loss ratio is computed on the basis of a three-year average. The credibility factor, which reflects the degree of confidence the ratemaker assigns to the insured's past experience as an indicator of future experience, varies with the number of losses observed during the experience period.

The experience rating formula used in general liability insurance illustrates the principle. The formula is the following:

Assuming, for the purpose of illustration, that the expected loss ratio is 60 percent and that the insured has achieved a 30 percent loss ratio, and further that the credibility factor is. 20, the computation would be the following:

![]()

The comparison of the actual loss ratio and the expected loss ratio indicates a 50 percent reduction in premium. However, the indicated reduction is tempered by the credibility factor, resulting in a 10 percent credit.

In most instances, the use of experience rating is mandatory for those insureds whose premiums exceed a specified amount.

Retrospective Rating A retrospective rating plan, or retro plan, is a self-rated program under which the actual losses during the policy period determine the final premium for the coverage, subject to a maximum and a minimum. A deposit premium is charged at the inception of the policy and adjusted after the policy period has expired to reflect actual losses incurred.4 In a sense, a retro plan is like a cost-plus contract, the major difference being that it is subject to a maximum and a minimum. The formula under which the final premium is computed includes a fixed charge for the insurance element in the plan (the fact that the premium is subject to a maximum), the actual losses incurred, a charge for loss adjustment, and a loading for the state premium tax. Retro rating is used in the field of workers compensation, general liability, automobile, and group health insurance. However, only large insureds will usually elect these plans.

Adjusting the Level of Rates When rates are initially established for any form of insurance, the rate is by definition an arbitrary estimate of what losses are likely to be. Once policies have been written and the loss experience on the policies emerges, the statistical data generated become a basis for adjusting the level of rates. Past losses are used as a basis for projecting future losses, and the anticipated losses are combined with estimated expenses to arrive at the final premium.

Any change in rate levels indicated by raw data is usually tempered by a credibility factor, which reflects the degree of confidence the ratemakers believe they should attach to past losses as predictors of future losses. The credibility assigned to a particular body of loss experience is determined primarily by the number of occurrences, following the statistical principle that the greater the sample size, the more closely will observed results approximate the underlying probability. To obtain a sufficiently large number of observed losses for achieving an acceptable level of credibility, the ratemaker must sometimes include loss experience over a period of several years. The less frequent the losses in a particular line of insurance, the longer the period needed to accumulate loss statistics necessary to achieve a given level of credibility.

One of the principal drawbacks of a long experience period is that when the interval is too long, the underlying conditions that influence frequency and severity are likely to have changed, and adjustments reflecting such changes must be included in the rate-making process. One approach is to weigh the experience of the most recent years more heavily than that of the earlier years. Another technique is the use of trend factors. A trend factor is a multiplier calculated from the trend in average claim payments, the trend of a price index, or some similar series of data. The trend indicated by past experience is usually extended into the future to the midpoint of the period for which the rates will be used.

Catastrophe Modeling and Ratemaking Given the rash of catastrophes that have occurred during the past decade, most insurers have adopted a tool known as catastrophe modeling, originally used for underwriting but increasingly employed for rating purposes. Catastrophe modeling (also called cat modeling) uses computer simulations based on experience and the insurer's known distribution of insured property. Insurers initially adopted cat modeling to measure their exposure in areas where earthquakes and hurricanes are likely. Increasingly, they are suggesting that the cat models may be an appropriate tool for ratemaking. For exposures such as earthquakes, characterized by low frequency and high severity, past experience may be an inadequate predictor of the future. One problem is that most of the cat models that have been developed thus far are proprietary products and their designers are unprepared to divulge the programming on which the models are based. Some regulators have been concerned over the “black-box” nature of cat modeling.

Many insurers who had relied on cat models experienced greater losses from Hurricane Katrina than they were expecting. The poor performance of the models, coupled with new scientific theories about the relationship between global warming and hurricane intensity, led the major modeling firms to revise their models in 2006. This has resulted in higher estimates of catastrophic hurricane loss and higher rates for hurricane insurance in coastal areas. It seems likely that cat models will continue to increase in importance.

Legend of Actuarial Precision Public opinion to the contrary, insurance ratemaking is not an exact science. The law of large numbers and the experience of the past permit actuaries to make estimates about future experience, but these must be qualified. When estimating future experience, the actuary implicitly says, “If things continue to happen in the future as they have in the past, this is what will happen.” But things do not happen in the future as they have happened in the past; some adjustment must be made to allow for changes that are likely to modify future losses. But even the adjustments to allow for deviations from past experience may be inadequate, particularly when the magnitude of the deviations is greater than anticipated. Of course, if the future differs from the past favorably, there is no great problem. However, if the deviation is adverse, the rate predicated on past experience may prove inadequate.

A major distinction between the fields of property and liability insurance and life insurance has been the differences in the deviation of present from past experiences. In the case of life insurance, we have seen a continued improvement in life expectancy. This has benefited insurance companies in two ways. First, since people have been living longer than originally expected, the insurers have been permitted to delay payment of funds, which can continue to be invested. In addition, the people who have lived longer than anticipated have paid premiums on their policies longer than expected.

In the property and liability field, results have deviated from those expected, but in this case, the outcome has been less favorable for insurers. Inflationary pressures, which push up the cost of repairs and construction, rising medical costs, an increasing rate of automobile accidents, soaring liability judgments, and other similar factors have all acted to the detriment of insurance companies. Inflation does not affect the loss under a life insurance policy because of the agreement to pay a fixed sum of dollars. In property and liability insurance, however, departures from past experience have caused severe difficulties.5

![]()

PRODUCTION

![]()

The production department of an insurance company, sometimes called the agency department, is its sales or marketing division. This department supervises the external portion of the sales effort, which is conducted by the agents or salaried representatives of the company. The various marketing systems under which the outside salespeople operate were discussed in Chapter 5.

The internal portion of the production function is carried on by the production (or agency) department. It is the responsibility of this department to select and appoint agents and assist in sales. In general, it renders assistance to agents in technical matters. Special agents, or people in the field, assist the agent directly in marketing problems. The special agent is a technician who calls on agents, acting as an intermediary between the production department and the agent. This person renders assistance when needed on rating and programming insurance coverages and attempts to encourage the producers.

![]()

UNDERWRITING

![]()

Underwriting is the process of selecting and classifying exposures. It is an essential element in the operation of any insurance program, for unless the company selects from among its applicants, the inevitable result will be selection adverse to the company. As we noted in Chapter 2, the future experience of the group to which the rates are applied will approximate the group on which those rates are based only if both have approximately the same loss-producing characteristics. There must be the same proportion of good and bad risks in the group insured as there were in the one from which the basic statistics were taken. The tendency of the poorer than-average risks to seek insurance to a greater extent than the average or better-than-average risks must be blocked. The main responsibility of the underwriter is to guard against adverse selection.

It is important to understand that the goal of underwriting is not the selection of risks that will not have losses. It is to avoid a disproportionate number of bad risks, thereby equalizing the actual losses with the expected ones. In addition to this goal, other objectives exist. While attempting to avoid adverse selection through rejection of undesirable risks, underwriters must secure an adequate volume of exposures in each class. In addition they must guard against congestion or concentration of exposures that might result in a catastrophe.

Few factors are as important to the success of the insurance operation as the underwriting function, for it is directly connected with the adequacy of rates. Actuaries compute the rates. The underwriter must determine into which of the classes, if any, each exposure unit should go. Poor underwriting may wipe out the efforts of the actuary, rendering a good rate inadequate. For this reason, those who perform the underwriting function must develop a keen sense of judgment and a thorough knowledge of the hazards associated with various types of coverage.

The underwriting process often involves more than acceptance or rejection. In some instances, an exposure that is unacceptable at one rate may be written at a different rate. In the life insurance field, for example, applicants may be classified as standard, preferred, substandard, and uninsurable. Standard risks are persons who, according to the company's underwriting standards, are entitled to insurance without a rating surcharge or policy restrictions. The preferred risk classification includes those whose mortality experience, as a group, is expected to be above average and to whom the insurer offers a lower-than-standard rate. The most common preferred class today consists of nonsmokers, for whom many insurers offer a preferred risk rate.

Substandard risks are persons who, because of a physical condition, occupation, or other factors, cannot be expected, on average, to live as long as people who are not subject to these hazards. Sub-standard applicants are insurable but not at standard rates. Policies issued to substandard applicants are referred to as rated policies (or extra risk policies) and require a higher-than-standard premium rate to cover the extra risk when, for example, the insured has impaired health or a hazardous occupation. Usually, substandard risks will pay a percentage surcharge, a flat additional premium, or in some cases, they will receive a policy subject to restrictions not included in the policies for standard risks. Most life insurers use a numerical rating system under which a point value is assigned for each type of physical disability or negative influence. The total of all points represents the expected mortality increase over that which is expected for standard or normal risks. The surcharge may apply only for a period of time and then disappear, or it may continue throughout the policy. In some situations, the policies issued to substandard risks may limit the death benefit during the first few years to the premiums paid.

Finally, some applicants are uninsurable. The applicants may be uninsurable because of high physical or moral hazard, or if they suffer from a rare disease or have a situation unique for which the insurer does not have the experience to derive a proper premium.

![]()

The Agent's Role in Underwriting

Because the application for the insurance originates with the agent, this person is often called a field underwriter. The use of the term underwriter in reference to an agent is more common in the field of life insurance than in property and liability, which is surprising considering the agent plays a far more important role in the underwriting process in the latter type of insurance. In fact, a part of the compensation of property and liability insurance agents is based on the profitability of the business they write. This is accomplished through a device known as a contingency contract or profit-sharing contract, the terms of which provide the agents with an additional commission at the end of the year if the business they have submitted has produced a profit for the company. The intent of these profit-sharing agreements is to encourage the agents to underwrite in their office.6

![]()

Underwriting Policy

Underwriting begins with the formulation of the company's underwriting policy, which is generally established by the officers in charge of underwriting. The underwriting policy establishes the framework within which the desk underwriter makes decisions. This policy specifies the lines of insurance that will be written as well as prohibited exposures, the amount of coverage to be permitted on various types of exposure, the areas of the country in which each line will be written, and similar restrictions. The desk underwriter, as the individual who applies these regulations to the applications is called, is usually not involved in the formation of the company underwriting policy.

![]()

Process of Underwriting

To perform effectively, the underwriter must obtain as much information about the subject of the insurance as possible within the limitations imposed by time and the cost of obtaining additional data. The desk underwriter must rule on the exposures submitted by the agents, accepting some and rejecting others that do not meet the company's underwriting requirements. When a risk is rejected, it is because the underwriter feels that the hazards connected with it are excessive in relation to the rate. The underwriter obtains information regarding the hazards inherent in an exposure from four sources:

- Application containing the insured's statements

- Information from the agent or broker

- Information from external agencies

- Physical examinations or inspections

Application The basic source of underwriting information is the application, which varies for each line of insurance and each type of coverage. The broader and more liberal the contract, usually the more detailed the information required in the application. The questions on the application are designed to give underwriters the information needed to decide if they will accept the exposure, reject it, or seek additional information.

Information from the Agent or Broker In many cases, the underwriter places much weight on the recommendations of the agent or broker. This varies, of course, with the experience the underwriter has had with the particular agent in question. In certain cases, the underwriter will agree to accept an exposure that does not meet the underwriting requirement of the company. Such exposures are referred to as accommodation risks because they are accepted to accommodate a valued client or agent.

Information from External Agencies In most cases, the underwriter will request a report from an external agency that specializes in providing information about individuals or organizations to their customers. These include credit bureaus, cooperative information bureaus within the insurance industry, and public agencies, such as a state department of motor vehicles. In the case of an application for commercial insurance, the underwriter may request a Dun & Bradstreet report. For the individual auto insurance buyer, the underwriter will request a credit report and a copy of the individual's driving record from the state department of motor vehicles. Sometimes, the underwriter will request a report from a company that specializes in investigations. All the information is pertinent in the decision to accept or reject the application. For example, the financial status of the applicant is important in the property and liability field and in the life insurance field although for different reasons. In the property and liability field, evidence of financial difficulty may be an indication of a potential moral hazard. In life insurance, there is concern because an individual who purchases more life insurance than is affordable is likely to let the policy lapse, a practice that is costly to the company.

In addition to the information available from public sources and credit bureaus, the underwriter may seek information from specialized databases designed for insurance companies. For example, life insurers may obtain information from the Medical Information Bureau (MIB), which maintains centralized files of the physical condition of applicants who have applied for life insurance. In the property and liability field, ChoicePoint maintains a database of claim history information called the Comprehensive Loss Underwriting Exchange (CLUE database). More than 95 percent of insurers writing automobile coverage provide claims data to CLUE, and insurers may search the database to obtain the applicant's prior claims history. The database maintains a history of property insurance claims, in which more than 90 percent of insurers writing homeowners insurance participate.

Physical Examinations or Inspections In life insurance, the primary focus is on the health of the applicant. The medical director of the company lays down principles to guide the agents and desk writers in the selection of risks, and one of the most critical pieces of intelligence is the physician's report. Physicians selected by the insurance company supply the insurer with medical reports after a physical examination; these reports are an important source of underwriting information. In the field of property and liability insurance, the equivalent of the physical examination in life insurance is the premises inspection. Although such inspections are not always conducted, the practice is increasing. In some instances this inspection is performed by the agent, who sends a report to the company with photographs of the property. In other cases, a company representative conducts the inspection.

![]()

Postselection Underwriting

In some lines of insurance, the insurer has the opportunity periodically to reevaluate its insured. When the coverage in question is cancellable or optionally renewable,7 the underwriting process may include postselection (or renewal) underwriting, in which the insurer decides if the insurance should be continued.

When a review of the experience with a particular policy or account indicates the losses have been excessive, the underwriter may insist on an increased deductible at renewal. In other instances, the underwriter may decide that the coverage should be discontinued and will decline to renew it or cancel it outright. Insurance companies differ in the extent to which they exercise their renewal underwriting options. In certain fields, such as auto insurance, some insurers are selective and show little hesitation in refusing to renew or canceling an insured who has demonstrated unsatisfactory loss experience.

Restrictions on Postselection Underwriting In addition to the fact that postselection underwriting is obviously possible only with policies that may be canceled or in which renewal is optional with the insurer, the ability of insurers to engage in postselection underwriting is considerably less in some lines than in the past. Because cancellation or the refusal of the insurer to renew some forms of insurance can work an undue hardship on the insured, many states have enacted statutes or have imposed regulations that restrict the insurer's right to exercise these options.

Some laws merely require the insurer to give advance notice of its intent to refuse renewal. These laws were designed to prevent an insurer from canceling or from refusing to renew without providing adequate time for the insured to obtain replacement coverage. In some cases, the laws prohibit midterm cancellation, except for certain specified reasons, once a policy has been in effect for a designated period of time, such as 60 days. In addition, the laws of many states prohibit insurers from canceling or refusing to renew coverage because of an insured's age, sex, occupation, race, or place of residence. In most cases, the laws require the insurer to furnish an explanation of the reason for cancellation or declination.

Although the restrictions on the right of a company to cancel or refuse to renew have been beneficial in many areas, they have also made it harder to obtain insurance. When legislative restraints are imposed on the insurers' ability to engage in postselection underwriting, insurers typically become increasingly selective before issuing a policy in the first place.

![]()

Credit Scoring

For the past 20 years, insurance companies have used an individual's credit history as a tool for underwriting auto and homeowners insurance, a practice that has sometimes been a point of controversy. Originally, credit scoring was developed for use by lenders in judging the credit risk of applicants for mortgages, car loans, and credit cards. Credit bureaus have long provided lenders with information on individuals' credit histories. Credit scoring goes further; it quantifies this history as a score, based on statistical correlation between such factors as the record of credit payments by groups of individuals and the likelihood of credit default. These scores, known as FICO scores (after Fair Isaac Corporation) range from 375 to 900. In the case of insurance, the scores are developed based on the relationship between credit information and insurance losses. These are known as insurance scores. The leading provider of credit-based insurance scores to the insurance industry is the Atlanta-based firm ChoicePoint, an offshoot of the Equifax credit-reporting company. ChoicePoint maintains a database that serves as the basis for the scores it generates.

Critics argue that use of credit scoring for insurance underwriting decisions is inappropriate and that a person's credit history and driving are unrelated. They also argue that using insurance scores has an adverse impact on low-income and minority consumers. Many insurers also use credit scores in their rating system, adding to the controversy. Insurers and independent actuaries respond that the correlation between credit scores and insurance loss ratios is indisputable and that the statistical models used in credit scoring allow insurers to segment applicants according to their likelihood of loss and price insurance with greater precision.

The link between credit scores and the likelihood of insurance losses is plausible and logical. In a sense, a credit score is a report card on how the individual has managed credit risks. It is reasonable to assume that people who are responsible in managing these credit risks will be responsible in managing their pure risks.

In July 2007, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) released a comprehensive study of credit-based insurance scores and their impact on consumers. It concluded that the scores are effective predictors of risk under automobile insurance policies and may result in benefits for consumers. The scores enable insurers to evaluate risk with greater accuracy, which may make them more willing to offer insurance to higher-risk customers. They may reduce expenses by making the process of granting and pricing insurance quicker and cheaper. Finally, the FTC concluded that insurance scores appear to have little effect as a “proxy” for an individual's racial or ethnic group.8

The use of credit information in insurance underwriting is regulated by federal law, under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) and the Equal Opportunity Act. Among other requirements, the FCRA requires the insurer to notify the consumer if an adverse action is taken based on the insurance score. Consumers may see their credit reports and dispute inaccurate information. In addition to the federal protections, nearly all states have adopted some restriction on the use of credit-based insurance scores. In most states, insurers may not use credit information as the sole basis for increasing rates or denying, canceling, or nonrenewing a policy. Most states have placed limits on the use of some credit information (e.g., bankruptcy resulting from health care expenses) and require the insurer to re-underwrite and re-rate applicants when it is found that incorrect or incomplete credit history information has been used. Finally, a small number of states (Georgia, Hawaii, Maryland, Oregon, and Utah) have gone further, effectively banning the use of credit-based scores under certain circumstances.9

![]()

Predictive Analytics

A credit score is an example of a predictive model. Insurers or credit bureaus analyze the data available to them to predict certain behaviors of the individual, such as their likelihood of paying their debts and their propensity to loss. With improvements in technology and lower costs for storing large amounts of data, more information is available on individuals, and the ready access of this information has begun to influence how insurers price and underwrite their policies. Predictive analytics is the term used for the mining of data to predict outcomes, such as whether an individual is likely to purchase a particular product, whether a claim is likely to be fraudulent, and whether an individual is likely to have losses. Using statistical techniques, insurers can identify those characteristics that relate to loss experience and reflect that in pricing. In the case of auto insurance, as discussed in Chapter 30, there is a movement toward telematics, in which information about a consumer's driving behavior is obtained from a device attached to the vehicle, and that information is used to modify the premium. While most of this activity has been in the area of pricing, particularly in automobile insurance, developments are gradually expanding into other areas, including fraud detection and claims handling. The result is that insurers are able to segment their market and target their activities, including marketing and pricing, using a variety of sources.

Predictive analytics can raise issues related to privacy and equity, comparable to the issues that arose as insurers increased their use of credit scoring. As these activities spread, they are likely to get greater attention from policymakers.

![]()

LOSS ADJUSTMENT

![]()

One basic purpose of insurance is to provide for the indemnification of those members of the group who suffer losses. This is accomplished in the loss settlement process, but it is sometimes more complicated than just passing out money. The payment of losses that have occurred is the function of the claims department. Life insurance companies refer to employees who settle losses as claim representatives or benefit representatives. The nature of the difficulties frequently encountered in the property and liability field is apparent because employees of the claims department in this field are called adjusters.

The insurance company must pay its claims fairly and promptly, but as important, the company must resist unjust claims and avoid overpayment of them. The view is rapidly increasing among insurers that prompt, courteous, and fair claim service is one of the most effective competitive tools available to a company.

![]()

Adjusters

Broadly speaking, Adjuster are individuals who investigates losses. They determine the liability and the amount of payment to be made. Adjusters include agents as well as staff, bureau, independent, and public adjusters. Agents can commonly function as adjusters in the case of small property losses. Many agents have been granted draft authority by their companies, which means they are authorized to issue company checks in payment of losses up to some stipulated amount. Even in cases in which the amount of the loss exceeds the draft authority, agents may handle the settlement of the loss.

Most insurers employ adjusters who are salaried representatives of the company. The use of a company staff adjuster in a given area is dictated by the amount of work available. In a locality where the company has a large volume of claims, it will use a salaried staff adjuster in preference to an adjustment bureau or an independent adjuster. If the volume of claims is too small to support a full-time adjuster, the company will contract for adjusting service. It is economically unfeasible to maintain an adjuster in every area in which the company writes insurance. Likewise, it would be too expensive to send an adjuster into a distant area for the purpose of adjusting one loss. In such cases, the insurer may use an adjustment bureau. The adjustment bureaus were originally organized and owned by insurers for the purpose of settling fire losses. Although the insurers that originally owned the bureaus have relinquished their ownership, the organizations continue to be referred to as bureaus.

As an alternative, the company may hire an independent adjuster, who does not work for a bureau but instead contracts services directly to the insurance company. These adjusters normally do not handle claims for a single company but work for any firm involved in the community and does not have a staff adjuster or adjusting bureau. The independent adjuster bills each company directly for the expense of adjustment.

The public adjuster differs from the other types discussed. Unlike the other adjusters, all of whom represent the insurance company in the loss settlement process, the public adjuster represents the policyholder. Public adjusters are employed by insureds who has suffered a loss and do not feel able to handle their own claim. A public adjuster is a specialist available to the insured. The most common method of compensation for public adjusters is a contingency fee basis, under which the adjuster collects a percentage of the settlement; the usual fee is 10 percent of the amount recovered from the insurance company. In return for this fee, the public adjuster performs the actions normally required of the insured, such as preparing estimates of the loss, presenting the amount of the claim to the insurance company, and negotiating the final settlement. A limited number of public adjusters hold one of two professional designations granted by the National Association of Public Insurance Adjusters. The Certified Professional Public Adjuster (CPPA) designation and the Senior Professional Public Adjuster (SPPA) designation are granted to public adjusters who pass a rigorous examination.

![]()

Courses of Action in Claim Settlement

Two basic courses of action are open to the company when confronted with a claim: pay or contest. In most cases, there is little question concerning coverage, and payment of the loss is the most common procedure. In those instances when the company feels a claim should not be paid, it will deny liability and contest the claim. The company might deny payment on two basic grounds: because the loss did not occur or because the policy does not cover the loss. A loss might not be covered under the policy because it does not fall within the scope of the insuring agreement, it is excluded, it happened when the policy was not in force, or the insured violated a policy condition.

![]()

Adjustment Process

In determining whether to pay or contest a claim, the adjuster follows a relatively set settlement procedure with four main steps: notice of loss, investigation, proof of loss, and payment or denial of the claim. The details of these steps vary with the type of insurance.

Notice of Loss The first step in the claim process is the notice by the insured to the company that a loss has occurred. The requirements differ from one policy to another, but in most cases, the contract requires that the notice be given “immediately” or “as soon as practicable.” Some contracts stipulate that notice be given in writing, but even in these, the requirement is not strictly enforced. Normally, the insured gives notice that a loss has occurred by informing the agent, and this satisfies the contract.

Investigation The investigation is designed to determine if there was a loss covered by the policy and, if so, the amount of the loss. In deciding whether there was a covered loss, the adjuster must determine a loss occurred and then whether the loss is covered by the policy. Determination as to whether a loss occurred is the simpler of the two. There are, of course, instances in which the claimant attempts to defraud the insurer, and in some instances payment is made where there has not been a loss. Once it has been determined a loss has occurred, the adjuster must determine whether the loss is covered under the policy. First, was the policy in effect at the time of the loss? If the policy is newly issued, did the loss take place before the policy became effective? Or at the other end of the time spectrum, did the policy expire before the loss took place? Once it has been established that the loss took place during the policy period, the possibility exists that the insured might have violated a condition that caused the suspension or voidance of the contract. If it appears that the policy was in effect at the time of the event and there was a loss, was the peril causing the loss insured against in the policy? In the case of property insurance, does the property damaged or lost meet the definition of the property insured? The location of the property is another question because some contracts cover property only at a specific location or are applicable only in certain jurisdictions. Finally, the adjuster must decide if the person making the claim is entitled to payment under the terms of the policy.

If the answer to all these questions is yes, the loss is covered. Yet to be determined is the amount of the loss, which can be more complicated than the determination of whether coverage applied.

Proof of Loss Within a specified time after giving notice, the insured is required to file a proof of loss. This is a sworn statement that the loss has taken place and gives the amount of the claim and the circumstances surrounding the loss. The adjuster normally assists the insured in the preparation of this document.

Payment or Denial If all goes well, the insurance company draws a draft reimbursing the insured for the loss. If not, it denies the claim. The claim may be disallowed because there was no loss, the policy did not cover the loss, or the adjuster feels the amount of the claim is unreasonable.

![]()

Difficulties in Loss Settlement

Disagreements will occur regarding loss settlements. In some instances, the insured will mistakenly feel a loss should have been covered under the policy when it was not. Adjusters, being human, also err, and there are occasions when a legitimate claim is denied. In addition to the question of whether the loss is covered, the amount of the loss is a continuing source of trouble. Value in most instances is a matter of opinion, and we should not be surprised that the insured and the adjuster may differ regarding the amount of the loss. For these reasons, the adjuster's role is a delicate one. They must be fair and must not leave the insured disgruntled. This is difficult when a loss is not covered.

On the surface, it would seem that an insured is relatively powerless against the insurance company in the event of a dispute. This is not the case. In those cases in which the disagreement is over the amount of the loss, most policies provide for compulsory arbitration on the request of either party. In the case of a denial based on an alleged lack of coverage, the insured who feels unfairly treated may appeal to the state regulatory authority, which is charged with the protection of the consumer's interest. Finally, the insured has recourse through the courts. In some instances, the only alternative remaining to the insured is to bring suit against the insurer.

![]()

THE INVESTMENT FUNCTION

![]()

As a result of their operations, insurance companies accumulate large amounts of money for the payment of claims in the future and to manage on behalf of others. In 2012, industry invested assets exceeded $7 trillion assets total over $7 trillion. It would be a costly waste to permit these funds to remain idle, and it is the responsibility of the insurer's finance department or a finance committee to properly invest them.

Because a portion of their invested funds must go to meet future claims, the primary requisite of insurance company investments is safety of principal. In addition, the return earned on investment is an important variable in the rating process: Life insurance companies assume some minimum rate of interest earnings in their premium computations. Increasingly, property and liability insurers are required to include investment income in their rate calculations. It may be argued that even when investment income is not explicitly recognized, it subsidizes the underwriting experience and is, therefore, a factor in ratemaking in this field.

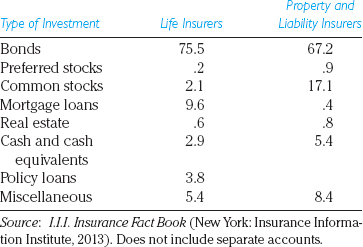

TABLE 7.1 Percentage Composition of Insurer Investments

The percentage composition of investments for life insurers and property and liability insurers is indicated in Table 7.1. The largest component of the investment portfolio for both types of insurers is bonds. Life insurers invest 75 percent of their general account assets in bonds, over half of which are corporate bonds. Property and liability insurers invest 68 percent of their assets in bonds, with about 40 percent of these in state, federal, and municipal bonds. Life insurers invest fewer than 3 percent of their general fund assets in common stocks10, whereas property and liability insurers invest more than 15 percent of their assets in stocks. Other differences are the mortgages, real estate investments, and policy loans of life insurers, and the receivables from agents of property and liability insurers.

![]()

MISCELLANEOUS FUNCTIONS

![]()

In addition to those discussed, various other functions are necessary for the successful operation of an insurance company. Among these are the legal, accounting, and engineering functions.

![]()

Legal

The legal department furnishes legal advice of a general corporate nature to the company. In addition, it counsels on such matters as policy forms, relations with agents, compliance of the company with state statutes, and the legality of agreements. It may or may not render assistance to the claims department in connection with claim settlements. Many insurers have a separate legal staff as a part of the claims department independent from the legal department.

![]()

Accounting

Historically, the primary function of the accounting department has been the recording of company operating results and the maintenance of all accounting records necessary for the company's periodic financial statements, especially the report to the commissioner of insurance. Insurance company accounting is a highly specialized field. In the past, the principal focus has been on external reporting, primarily because of the requirements of the report to the commissioner. Companies also maintain internal information systems with greater emphasis on internal or managerial accounting.

![]()

Engineering

The engineering department, which is unique to the property and liability insurers, is charged with the responsibility of inspecting premises to be insured to determine their acceptability. In addition, the engineering department benefits the company's insured by making loss-prevention recommendations.

![]()

APPENDIX

RETROSPECTIVE RATING PLANS

Retrospectively rated programs are an approach to rating in which transfer and retention are combined in dealing with risk. Retrospective rating is an alternative to guaranteed-cost programs and allows the premium for each period of protection to vary, depending on the loss experience for that period. It differs from guaranteed-cost plans in that the premium is variable, based on the insured's loss experience.

A retrospectively rated insurance policy is a self-rated plan under which the actual losses experienced during the policy period determine the final premium for the coverage, subject to a maximum and a minimum. A deposit premium is charged at the inception of the policy, and this premium is adjusted after the policy period has expired to reflect the actual losses incurred. The formula under which the final premium is computed includes a fixed charge for the insurance element in the program (i.e., the fact that the premium is subject to a maximum), the actual losses incurred, a charge for handling losses, and the state premium tax.

In a sense, a retrospectively rated policy is like a cost-plus contract; the major difference is that the premium is subject to a maximum and a minimum. Viewed from a different perspective, a retrospective program is like a self-insured program up to the maximum premium. The lower the losses of the insured, the lower the final premium; the higher the losses, the higher the premium.

![]()

THE RETROSPECTIVE FORMULA

![]()

To provide a basis for the discussion of the retrospective approach to rating, it may be helpful to examine the retrospective rating formula used in workers compensation insurance. The basic formula used in this line of insurance is the following:

![]()

The basic premium is the fixed-cost element in the plan, which does not vary with the level of losses. Converted losses are actual losses sustained, plus a percentage of losses for loss adjustment expense. The tax multiplier is a variable charge, equal to the premium that will be due to the state from the insurer, and is based on the total premium generated by the formula. The final premium for the year is determined by adding the basic premium to actual losses and loss adjustment expense, and then adding the amount of the premium tax that will be payable by the insurer to the state.

Although the terminology tends to be confusing, we can illustrate the elements in the retrospective rating formula by indicating one set of values for each of the elements in the formula. A large manufacturer with a workers compensation experience-rated premium of $100,000, for example, might elect a retrospectively rated plan under which the insurer would charge a fixed cost (the basic premium) of $20,000, plus the amount of all losses adjusted to include the cost of loss adjustment expenses (the loss conversion factor) and 3 percent of this total for the premium tax, all subject to a maximum of $150,000 and a minimum of $50,000. At the end of the policy period the final computation would generate a premium based on the amount of losses as illustrated by the following schedule:

The insurer determines the final premium for the policy after the year is over by adding the basic premiums ($20,000) to actual losses incurred plus the cost of adjusting those losses. The cost of adjusting losses is indicated by the loss conversion factor. Losses are surcharged 14 percent to cover loss adjustment expense (i.e., actual losses are multiplied by 1.14). After the charges for losses, loss adjustment expense and the basic premium are combined, this total is then increased by the amount of the premium tax that the insurer must pay to the state. In this way, the premium will vary directly with losses up to the point at which the maximum premium is reached. In this way, the premium varies directly with the loss experience during the policy period.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

rate

premium

gross rate

loading

pure premium

expected loss ratio

loss ratio

expense ratio

permissible loss ratio

combined ratio

class rating

individual rating

judgment rating

schedule rating

experience rating

retrospective rating

credibility factor

trend factor

catastrophe modeling

special agent

Medical Information Bureau (MIB)

adjustment bureau

standard risk

preferred risk

substandard risk

uninsurable

rated policies

contingency contract

profit-sharing contract

accommodation risk

postselection underwriting

benefit representative

staff adjuster

independent adjuster

public adjuster

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. List and briefly explain the steps in the underwriting process.

2. What sources of information are available to the underwriter? Explain the importance of each source. Why are multiple sources necessary?

3. Sales representatives of property and liability insurance companies sometimes refer to the “sales prevention department.” What department of the company are they referring to? Explain.

4. Why is the pricing of the insurance product more difficult than pricing of other products?

5. What is the difference between a premium and a rate?

6. List and briefly explain the steps in the loss-adjustment process.

7. Briefly explain the nature of retrospective rating plans and why they are used.

8. List several reasons for which a claim might be completely denied.

9. Name the various types of adjusters used by property and liability insurers.

10. Distinguish between an independent adjuster and a public adjuster.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. How do you account for the feeling held by many people that something is almost “immoral” about an insurance company canceling a policy in the middle of the policy term? Do you agree or disagree with this position?

2. Do you agree with legislation imposing restrictions on the right of an insurance company to engage in postselection underwriting?

3. At one time it was suggested that the problem of providing insurance protection against loss by flood be met by providing coverage against the flood peril as a mandatory part of the Standard Fire Policy. Do you agree with this solution? Why or why not?

4. Do you think that loss adjustment would be most difficult in the field of life insurance, property insurance, or liability insurance? What training would you recommend for adjusters in each of these three fields?

5. “Pricing is more difficult in insurance than in other business fields, because the cost of production is not known until after the product has been delivered.” To what extent is this statement true and to what extent false?

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Insurance Company Operations, 3rd ed. Atlanta, Ga.: LOMA, 2012.

Kenney, R. Fundamentals of Fire and Casualty Strength, 4th ed. Dedham, Mass: Kenney Insurance Studies, 1967.

Insurance Administration, 4th ed. Atlanta, Ga.: LOMA, 2011.

Myhr, Ann E. Insurance Operations, Regulation, and Statutory Accounting, 3rd ed. Malvern, Pa.: American Institute for CPCU, 2011.

Popow, Donna. Property Loss Adjusting, 3rd ed. Malvern, Pa.: Insurance Institute of America, 2003.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| American Institute for CPCU | www.aicpcu.org |

| Casualty Actuarial Society | www.casact.org |

| Claims Magazine | www.claimsmag.com |

| Insurance Information Institute | www.iii.org |

| Insurance Marketing Communication Association | www.imcanet.com |

| ISO, A Verisk Company | www.iso.com |

| Life Office Management Association | www.loma.org |

| LIMRA, International, Inc. | www.limra.com |

| Medical Information Bureau | www.mib.com |

| National Association of Public Insurance Adjusters | www.napia.com |

| National Underwriter Company | www.nationalunderwriter.com |

| Society of Actuaries | www.soa.org |

| The American College | www.theamericancollege.edu |

![]()

1Much of the discussion of ratemaking in this chapter pertains to property and liability insurance. Because of the long-term nature of life insurance contracts, special complications mark the life insurance ratemaking process. Life insurance ratemaking and the actuarial basis for life insurance are treated in greater detail in Chapter 13.

2Schedule rating is used less frequently today than in the past. In 1976, the Insurance Services Office introduced a new class-rating program for many types of commercial buildings that had previously been schedule rated, leaving only the larger and more complex buildings to be schedule rated.

3Many companies use a merit-rating system for automobile insurance, in which the individual insured's premium is based on that person's past driving record, as indicated by at-fault accidents and certain traffic violations. While this represents a form of experience rating in the broadest sense of the term, it is more accurately classified as a form of class rating, in which the class is defined as those drivers with no “points,” those with one “point,” and so on.

4Retrospective rating is illustrated in the appendix to this chapter.

5An additional cause of these difficulties has been a degree of price inflexibility owing to the regulatory system.

6Beginning in the fall 2004, then New York Attorney General Eliott Spitzer initiated a series of regulatory actions aimed at curbing the use of contingent commissions by large brokers and insurance companies. The Illinois and Connecticut Attorneys General joined him in these efforts. As a result, several large brokers and insurance companies discontinued the use of contingent commissions for some or all lines of insurance. Most brokers and insurers, however, continue to use these compensation arrangements. Academic studies support their value in the marketplace. See, e.g., Carson, J., Dumm, R. and Hoyt, R., 2007. “Incentive Compensation and the Use of Contingent Commissions: The Case of Smaller Distribution Channel Members,” Journal of Insurance Regulation, 25(4): 53–67.

7Cancellation is the process of terminating coverage prior to the normal expiration date.

8See Credit-Based Insurance Scores: Impacts on Consumers of Automobile Insurance. A Report to Congress by the Federal Trade Commission, July 2007.

9For more information on the use of credit-based insurance scores and regulatory issues, www.naic.org/ciprkeyissues.htm.

10Exhibit 7.1 includes only general account assets. In addition, life insurers maintain separate accounts, which are segregated from the insurers' general investment account and are used primarily for retirement plans and variable life insurance products. About 79 percent of the assets in separate accounts are invested in equities, with another 4 percent invested in bonds.