CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Describe the common provisions of life insurance contracts

- Explain the purpose and importance of the incontestable clause in life insurance contracts

- Identify and explain the distinction among the various types of beneficiaries that may be designated in a life insurance contract

- Identify and describe the settlement options and explain the circumstances in which each of the settlement options might be used

Unlike many other insurance contracts, there is no standard policy form that must be used in life insurance. Although there is no uniform contract, the states have enacted legislation that makes certain provisions mandatory in life insurance policies. The most commonly required provisions include the following:

- The policy shall constitute the entire contract.

- There must be a grace period of 30 days or 1 month.

- The policy shall be contestable only during the first 2 years.

- Misstatement of age shall be cause for an adjustment in the amount of insurance.

- Reinstatement must be permitted.

- Participating policies shall pay dividends on an annual basis.

- Nonforfeiture values must be listed for at least 20 years.

- The nonforfeiture values to which the insured is entitled must be listed after the payment of three premiums.

- Loan values must be listed.

- Installment or annuity tables shall show the amount of benefits to which the beneficiary is entitled if the policy is payable in installments or as an annuity.

Some of these provisions pertain only to certain types of policies and do not, therefore, appear in all life insurance policies. For example, provisions relating to dividends are included only in participating contracts, while those relating to cash values are not found in term policies where there is no cash value. To provide a systematic basis for analysis, we have divided life insurance policy provisions into two classes: those that are included in every life insurance policy are discussed in this chapter; those that are included only in certain policies, or whose inclusion is optional, will be analyzed in Chapter 15.

![]()

INCEPTION OF THE LIFE INSURANCE CONTRACT

![]()

Coverage under the life insurance policy is effective as soon as the contract comes into existence. The fundamental question, then, is, When does the policy come into existence? The answer hinges on a detail in the eyes of many insureds: whether the first premium accompanies the application for insurance. If the application is sent to the insurer without the premium, it is considered an invitation to the insurer to make an offer, which it does by issuing a policy. There is no contract until the applicant has accepted the insurer's offer, which he or she does by taking the policy and paying the first premium. If the insured should die during the period between making the application and receiving the policy and paying the first premium, no benefits will be paid, for the policy has not come into existence. For the most part, this is not the usual procedure.

Normally, the premium accompanies the application for insurance. The company acknowledges receipt of the premium with a conditional binding receipt. The typical binding receipt makes the policy effective as of the date of application, provided the applicant is found to be insurable according to the underwriting rules of the company. If the individual does not meet the company's underwriting standards, it may offer a rated policy or a policy subject to limitations. This, in effect, represents a counteroffer by the insurer, and the applicant is again in the situation in which he or she may accept or reject the insurer's offer. A situation might arise in which the underwriter is forced to determine whether a deceased person would have qualified for insurance if he or she had not died. If the applicant would have qualified, then the company is bound to pay the death benefit since the policy went into effect conditionally at the time of the application.1

![]()

GENERAL PROVISIONS OF LIFE INSURANCE CONTRACTS

![]()

Although certain provisions are required by law, in many cases they are not spelled out exactly. However, the final wording adopted by the insurance company must be approved by the commissioner of insurance. In addition, even in the case of those provisions not required by law, competition generally forces them to be similar. So, although there is no “standard” life insurance policy, the provisions discussed here are common to all life contracts.

![]()

Entire Contract Clause

When the application is incorporated as a part of the policy contract, the representations of the insured become contractual provisions and can be used as evidence in a contest of the contract's validity. To prevent the use of other evidence, most states require the inclusion of a clause in life insurance policies stating the policy and the application attached to it constitute the entire contract between the insurer and the insured. The typical policy expresses this provision as follows:

This policy and the application, a copy of which is attached when issued, constitute the entire contract. All statements in the application, in the absence of fraud, shall be deemed representations and not warranties. No statement shall void this policy or be used in defense of a claim under it unless contained in the application.

In declaring the statements of the insured are to be considered representations and not warranties, the clause requires the insurer to prove the materiality of any misrepresentations by the insured. This provision is beneficial to the insured.

![]()

Ownership Clause

A life insurance policy is a piece of property. The policy may be owned by the individual on whose life the policy is written, by the beneficiary, or by someone else. In most cases, the insured is the policy owner. The person designated as the owner has vested privileges of ownership, including the right to assign or transfer the policy, receive the cash values and dividends, or borrow against it. At the death of the insured, the beneficiary becomes the owner of the policy.

![]()

Beneficiary Clause

The beneficiary is the person named in the life insurance contract to receive all or a portion of the proceeds at maturity of the policy. The designation of the beneficiary is an important aspect of the policy and is designed specifically to reflect the insured's decisions concerning the disposition of his or her insurance. In an endowment or retirement income policy, the beneficiary may be the insured or, in the event of the insured's death, the estate or a third party. In most instances, it is best not to name the estate as beneficiary, particularly when it is intended that the proceeds will go to certain individuals. If a specific beneficiary is named, the proceeds will be paid to the designated person or persons directly after the insured's death, and they will not be subject to estate administration, with its accompanying probate costs and creditors' claims against the insured. But most important, if a specific beneficiary is named, the payment of the proceeds will not be delayed until the entire estate has been settled.

A beneficiary may be primary or contingent. A primary beneficiary is the person first entitled to the proceeds of the policy following the death of the insured. A contingent beneficiary is entitled to the policy benefits only after the death of the primary or direct beneficiary.

The customary type of beneficiary designation is the donee or third-party beneficiary. The beneficiary may be a specific individual or a class designation. To ensure the insured's intentions are accomplished, he or she should designate the beneficiary or beneficiaries with care. For example, a man may wish that his wife be the primary beneficiary and his children by this wife are to be the class-contingent beneficiaries. Proper identification could be accomplished in this case by the designation of “my wife, Elizabeth Hallquist Jones” as the primary beneficiary and “the children of my marriage to Elizabeth Hallquist Jones” as the contingent beneficiaries. The children then would receive, and share equally, the proceeds if the wife should predecease the insured.2

Beneficiaries may be classified many ways, but for our purpose the most important variable is whether the insured reserves the right to change the designation. Beneficiary designations may be revocable or irrevocable. In the former, the insured reserves the right to change the designation at any time; in the latter, the insured imposes a restriction on the use of this right.

The revocable designation is used in the vast majority of life insurance contracts today. As the owner of the contract, the insured has the right to designate anyone as the beneficiary even if the person named has no insurable interest in the policyholder's life. If, at the inception of the contract, the insured designates a beneficiary and reserves the right to change this designation, then the change may take place at any time and any number of times during the term of the policy. This means that the interest of a revocable beneficiary is nothing more than an expectancy subject to all the rights and privileges that the insured may exercise in the contract. The insured is the complete owner of the contract and the revocable beneficiary cannot interfere in any manner with the insured's exercise of these rights. The insured may borrow on the policy, surrender the contract for cash value, assign the policy, or do anything else that he or she wishes without any legal interference from the beneficiary. The only time the beneficiary acquires a legal interest in the contract is at the insured's death. But even here, the right of the beneficiary to the proceeds is subject to the conditions of any settlement options selected by the insured.

If the insured designates an irrevocable beneficiary, the right to exercise the privileges granted by the contract, except with the consent of the beneficiary, is lost; the insured loses complete ownership of the policy, which then becomes the joint property of beneficiary and insured. This means the insured cannot change the beneficiary designation without the latter's consent and the acquisition of a policy loan or an assignment of the contract will require the permission of the beneficiary. However, if the irrevocable beneficiary should predecease the insured, most policies today provide the interest of the beneficiary shall terminate and all rights in the contract will revert to the insured. As a consequence, the irrevocable beneficiary does not become the complete owner of the policy; this person's interest is conditionally vested along with that of the insured.

Collateral Assignment In the designation of the beneficiary, the insured (owner) designates the party to receive the policy proceeds at death. The insured can assign a part of the policy proceeds to another party after the policy is issued. This is often done as security for a loan. Because the assignment of the policy proceeds serves as a collateral for the loan, the transaction is called a collateral assignment. Collateral assignment is a partial and usually temporary transfer of ownership rights to the lender (or other party).

![]()

Incontestable Clause

One unusual provision that is required in life policies is the incontestable clause. The usual policy provision reads as follows: “This policy shall be incontestable after it has been in force during the lifetime of the insured for two years from the date of issue.”3 This means the contract's validity cannot be questioned for any reason after it has been in force during the lifetime of the insured for two years. The rationale for this restriction is based on the long-term nature of the life insurance contract. It is to assure the person insured and the beneficiary that they will not be harassed by lawsuits long after the original transaction and at a time in which all evidence of the original transaction has disappeared and original witnesses have died. The effect of the clause is not that of justifying a contract involving fraud. The courts justify the clause on the grounds that they are not condoning fraud, but after an insurance company has been given a reasonable opportunity to investigate the validity of the contract, it should then relinquish its right on the grounds that the social advantages will outweigh the undesirable consequences.4

The clause is applicable for two years during the lifetime of the insured. This means that the death of the insured during the contestable period suspends the operation of the clause. If this were not the case and if the beneficiary knew that the insured had made material misrepresentations in the application, he or she could wait until the end of the two-year period before submitting the claim and would be protected against voidance of the contract because of the insured's fraudulent acts.5

![]()

Misstatement of Age Clause

The incontestability clause does not apply to the misstatement of age by the insured. Since the amount of insurance a given premium will purchase varies with the age of the insured, the applicants for insurance tend to understate their age.6 The misstatement of age clause provides that in the event the insured has misstated his or her age, the policy face amount will be adjusted to the amount of insurance the premium paid would have purchased at the correct age. In other words, the amount of the policy is adjusted; the contract is not voided. The typical policy provision reads as follows: “If the age of the insured has been misstated, the amount payable shall be such as the premium paid would have purchased at the correct age.”

For example, the premium on a certain policy is $20 per $1000 at age 40. The premium on the same policy is only $15 per $1000 at age 31. The insured in question was a particularly youthful-looking individual and convinced the agent and the insurance company that she was 31 years old, when in reality, she was 40. She purchased a $10,000 policy, paying the annual premium of $150. On her death, the insurance company discovered that she was 40 years old when the policy was issued. In this event, the company would pay 15/20 of the face amount, or $7500. This is the amount of insurance the individual could have purchased for the premium that she paid if she had given her correct age.

![]()

Grace Period

We have learned that the consideration for the insurance company's promise is the payment of the first premium by the insured. Although subsequent premiums are not a part of the legal consideration, they must be paid when due or the contract will end. A premium due date is designated in the policy, and the premium should be paid on or before that date. The insured may pay the premium annually, semiannually, quarterly, or monthly.

If the insured does not pay the premium on the due date, technically the contract will lapse. The time of lapsing, however, is subject to a modification that is in the nature of a grace period and is almost universally required by statute. A typical statement of the grace period clause in a life insurance contract is as follows:

A grace period of 31 days shall be allowed for payment of a premium in default. The policy shall continue in full force during the grace period. If the insured dies during such period, the premium in default shall be paid from the proceeds of this policy.

Thus, for example, if the premium due date is May 1, and the insured does not pay it on this date, the policy allows a grace period of 31 days before lapsing. If he or she should die on May 15, the proceeds of the policy will be paid but minus the amount of the premium in default. If the insured pays the premium before the end of the grace period, the policy continues in effect as if payment had been on time. The purpose of this clause is not to encourage procrastination in the payment of premiums (although it does) but rather to keep the policy from lapsing when the owner of the policy inadvertently neglects to pay the premium.

![]()

Reinstatement

Practically all permanent life insurance contracts permit reinstatement of a lapsed policy. However, the reinstatement is subject to certain specific conditions. The provisions of a typical contract read as follows:

This policy may be reinstated within five years after the date of premium default if it has not been surrendered for its cash value. Reinstatement is subject to (a) receipt of evidence of insurability of the insured satisfactory to the Company; (b) payment of all overdue premiums with interest from the due date of each at the rate of 6 percent per annum; and (c) payments or reinstatement of any indebtedness existing on the date of premium default with interest from that date.

Reinstatement is not an unconditional right of the insured. It can be accomplished only if the risk has not changed for the insurance company and only if, by payment of the back premiums with interest, the reinstated policy would have the same reserve as it would have had if the policy had not been lapsed. The conditions necessary are specific. First, reinstatement is possible only if at the time of lapsing the insured did not withdraw the cash value of the policy. Withdrawal of the surrender value in cash terminates the contract forever. Second, reinstatement must be effected within a specific time period, normally five years after the lapse. Third, the insured must provide proper evidence of insurability. His or her health must be satisfactory, and other factors, such as financial income and morals must not have deteriorated substantially. Fourth, reinstatement can be effected properly only if the insured pays the overdue premium plus interest and pays or reinstates any indebtedness that may have existed. These conditions may appear burdensome, and some may appear unnecessary. However, they are required if the contract is to be maintained in its original form and they are important if the insurance company is to avoid what would otherwise be a substantial element of adverse selection.7

![]()

Suicide Clause

Almost universally, suicide during a stipulated period after inception of the contract is excluded. A typical suicide exclusion reads as follows: “If within two years from the date of issue the insured shall die by suicide, whether sane or insane, the amount payable by the Company shall be the premiums paid.” Some companies, however, limit the suicide exclusion period to one year. The reason for the exclusion is, of course, that of protecting the insurer against a person who might purchase the insurance with the deliberate purpose of committing suicide.8 The assumption of the two years is that during this length of time, if the insured has not committed suicide, the reason for doing so will probably have disappeared. After the exclusion period is over, death by suicide is treated the same as any other cause of death, and coverage is justified on the assumption that it should be provided for as a hazard of life to which practically all people are subject.9

![]()

Aviation Exclusions

At one time, nearly all life insurance policies excluded death resulting from aviation. Today, most policies cover loss from aviation accidents although an additional premium may apply in the case of private pilots and the pilots and crews of commercial airlines. The single area in which aviation exclusions are still found is with respect to military aircraft, and the exclusion can usually be eliminated for an additional premium.

![]()

War Clause

During times of war, or when war appears imminent, insurance companies usually insert a clause in their policies that provides for a return of premium plus interest rather than payment of the face amount of the policy if the insured dies under excluded circumstances.

War exclusions may be divided into two classes: exclusions based on status and exclusions of results. Under a status-type clause, death while serving as a member of the military is excluded, regardless of cause. Under the results-type exclusion, coverage is denied only if the death results directly from war.10

The purpose of the war clause is not so much to avoid payment to beneficiaries of insureds who are killed in the war as to prevent adverse selection. If the clause were not put into policies sold during wartime, those who faced a higher chance of loss would obtain larger amounts of insurance than they might otherwise purchase. The result would be selection against the company.11

![]()

SETTLEMENT OPTIONS

![]()

The average person, in thinking about the settlement of life insurance policies, normally thinks of a lump sum being paid to the insured's beneficiary. While the vast majority of death claims are paid in a lump sum, a portion of life insurance death benefits is disbursed in some other manner. In addition to the lump-sum settlement, there are certain optional modes of settlement that may be used to pay out the proceeds of the policy. Normally, the owner (who in most cases is the insured) elects the option under which the proceeds of the policy are to be paid. If no election is in force when the policy becomes payable, the beneficiary is entitled to select the option desired. Unless the insured (owner) has made a provision that denies the right, the beneficiary may change to some other mode of settlement.

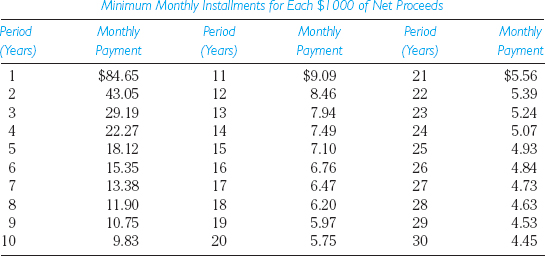

TABLE 14.1 Installments for a Fixed Period

![]()

Interest Option

Under the interest option, the proceeds of the policy may be left with the insurance company, to be paid out at a later time, in which case only the interest on the principal amount is paid to the beneficiary. A minimum rate of interest is guaranteed in the policy, but under participating options, many insurance companies pay excess interest above the guaranteed rate if additional interest is earned by the company.12 Normally, the interest option is selected when there are proceeds from other policies available for income, and the principal of the policy is not needed until some later time.

![]()

Installments for a Fixed Period

The insured may specify (or the beneficiary may elect) to have the proceeds of the policy paid out over some specified interval. The insurance company computes how much it can pay out of the policy proceeds and the interest on them during each of the required periods so the entire principal and interest will have been distributed by the end of the period. The rate of interest credited to the unpaid balance is specified in the policy, but as in the case of the interest option, excess interest may be payable under participating policies. The same is true of the other settlement options discussed in the paragraphs that follow. A typical schedule of installments for a fixed period is reproduced in Table 14.1. The longer the period of time for which the company promises to pay the installments, the smaller each installment must be. According to Table 14.1, a $100,000 policy would provide $1812 per month if paid over a 5-year period and only $983 if paid out over a 10-year period. These payments (and the other payments discussed below) are based on the contract's minimum guaranteed interest rate, which is 3.5 percent. If the insurer's investment earnings are higher than the guaranteed minimum, all installments will be increased to reflect the higher earned interest.

The fixed period selected may be any number of years, usually up to 30. This option is most valuable where the chief consideration is to provide income during some definite period, such as the child-raising years.

![]()

Installments of a Fixed Amount

The owner of the policy (or the beneficiary) may elect to have the proceeds of the policy paid out in payments of some fixed amount ($500, $1000, $1500, and so on) per month for as long as the principal plus interest on the unpaid portion of the principal will last. Since the amount of each installment is the controlling factor under this option, the length of time for which the payments will last will vary with the amount of the policy. In a sense, the installments-of-fixed-amount option is similar to the installment for a fixed period. Under one option, the amount to be paid determines the length of time the benefits will last, and under the other, the length of time for which the benefits are to be paid determines the amount of the benefits.

![]()

Life Income Options

In addition to the options listed, the policy gives the insured's beneficiary the right to have the proceeds paid out in the form of an annuity. In such cases, the proceeds of the policy are used to make a single-premium purchase of an annuity. Although the various life insurance companies list many life income options, they may be classified into four basic categories.

Straight Life Income Under a straight life income option, the proceeds of the policy are paid to the beneficiary on the basis of life expectancy. The beneficiary is entitled to receive a specified amount for as long as he or she lives but nothing more. If the beneficiary dies during the first year of the pay period, the company has fulfilled its obligations, and no further payments are made. Beneficiaries who live longer than the average are offset by those who live only a short time.

Life Income with Period Certain Under this option, the beneficiary is paid a life income for as long as he or she lives, but a minimum number of payments is guaranteed. If the beneficiary dies before the number of payments guaranteed has been made, the payments are continued to a contingent beneficiary. Normally, the period certain, as the time for which payments are guaranteed is known, is 5, 10, 15, or 20 years.

Life Income with Refund Under the life income with refund option, the beneficiary is paid a life income for as long as he or she lives, and if the policy proceeds have not been paid out by the time the beneficiary dies, the remainder of the proceeds will be paid to a contingent beneficiary. The life income with refund may be a life income with installment refund, in which case installments are continued until the contingent beneficiary has received the difference between the original policy proceeds and the amount received by the direct beneficiary, or it may be a cash refund. Under the cash refund, installments do not continue to the contingent beneficiary; instead, that individual is paid a lump sum.

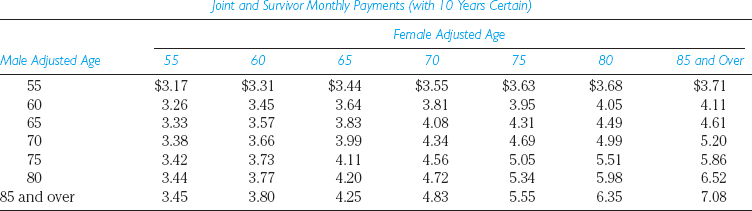

Joint and Survivor Income The joint and survivor income option is a somewhat specialized option, designed to provide income to two payees. The payments continue after the first of the two payees has died and stops with the death of the second. A modification of this plan provides that the benefit amount will be decreased when the first of the two payees dies. The benefit to the surviving payee will be either two-thirds or half (or some other fraction) of the original income amount. The benefit is computed on the basis of two lives, its amount depending on the age of both beneficiaries.

Payments The amount payable under any one of the life income options depends on the age and sex of the beneficiary, plus the plan selected. For obvious reasons, the company cannot afford to pay as high a monthly income if it guarantees to pay it for some guaranteed time period. When a period certain is selected, the mortality gains under the annuity are eliminated for whatever the length of the period certain. Table 14.2 illustrates a typical life income option table for single lives, and Table 14.3 details a joint and survivor life income option.

To illustrate the operation of Table 14.2, let us assume the policy proceeds amount to $100,000 and the beneficiary is a 70-year-old female. Because the life expectancy of women is greater than of men, a given number of proceeds dollars will provide a higher monthly income to a male than to a female. If our 70-year-old female beneficiary selects a life income without a period certain, she will receive a guaranteed payment of $506 a month for life, but payments will cease on her death, regardless of the amount that has been paid out. She may select a life income with 10 years certain, in which case the policy will pay $492 a month for as long as she lives, but at least for 10 years. The slight decrease in the amount payable under the 10-year-certain option as compared with the payment without a period certain results from there being no mortality gain to survivors during the first 10 years. If a 20-year period certain is selected, the amount of the monthly benefit is reduced more. Under the 20-year-certain option, the monthly benefit amount will be $448. Finally, the woman might select a life income with installment refund. Under this option, the insurer will pay her $458 a month for life, and at least until the full $100,000 has been paid out. At the age specified, the amount payable under the installment refund option is less than the amount payable under the life income with 10 years certain but slightly more than the amount payable under the life income with 20 years certain. This is because the guarantee to pay 20 years certain calls for a commitment to pay for a greater number of years than would be required to consume the original $100,000.

TABLE 14.2 Single Life—Life Income Payments

TABLE 14.3 Joint and Survivor Life Income Option

Table 14.3 indicates the payment that will be made under a joint and survivor life income option. Under this particular agreement, the company will make payments of the specified amount until both individuals have died, which is at least for 10 years. For example, assuming the same $100,000 in policy proceeds, with male and female beneficiaries both age 70, payment would be made in the amount of $434 a month. Payments would continue until the second payee has died, that is, jointly and to the survivor. If both payees die before the end of the 10-year period, payments will continue to a contingent beneficiary. Under other contracts, provisions might be made for a reduction in the benefit at the death of the first beneficiary.

![]()

Taxation of Policy Proceeds under Various Settlement Options

As a general rule, benefits payable to a beneficiary under a life insurance policy are not subject to taxation under the federal income tax except insofar as the benefits are composed in part of interest on the policy proceeds. When a life insurer pays death benefits to a beneficiary in a series of installments (under one of the installment options or a life income option), a part of each payment is considered a nontaxable death benefit, and a part is treated as taxable interest income. For example, suppose the proceeds of the insured's life insurance policy amount to $100,000. The spouse elects to take the proceeds under an installment option and receives $11,796 a year for 10 years. The $1796 in excess of the death benefit received each year is taxable as interest.

When proceeds are payable under one of the life income options, the taxable interest is determined by computing the portion of each installment that represents payment of principle, based on the beneficiary's life expectancy as indicated by gender-neutral mortality tables prescribed by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The difference between the amount of the installment and the excludable principal is taxable as interest income.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

binding receipt

entire contract clause

incontestable clause

misstatement of age clause

primary beneficiary

contingent beneficiary

direct beneficiary

revocable beneficiary

grace period

reinstatement provision

suicide exclusion

settlement options

life income with period certain

life income with refund option

life income with installment refund

installments for a fixed period

installments of a fixed amount

interest option

ownership clause

straight life income option

joint and survivor income

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. Some life insurance contract provisions are designed for the protection of the insured and some for the protection of the insurance company. Indicate whether each of the following provisions is designed for the benefit of the insured, the company, or both: (a) the entire contract provision; (b) the incontestability provision; (c) the suicide provision; (d) the misstatement of age provision.

2. Explain the difference among the insured, the owner, and the beneficiary of a life insurance policy. Give a specific example in which each party might be a different person.

3. Briefly distinguish between a direct beneficiary and a contingent beneficiary; between a revocable and an irrevocable beneficiary.

4. Explain in detail the obligation of the insurer under a straight life income option, life income with 10 years certain, and life income with installment refund.

5. Settlement options of life insurance policies include lump sum, the interest option, installments for a fixed period, installments of a fixed amount, and life income options. Explain each.

6. What are the rights of a person who is designated as an irrevocable beneficiary?

7. Describe the taxation of life insurance proceeds payable under the policy settlement options.

8. What is meant by reinstatement? Under what conditions may a policy that has lapsed be reinstated?

9. At age 30, John Doe applies for a life insurance policy, stating that he is 28 years old. The misstatement is discovered at the time of his death. Does it make any difference if the misstatement is discovered before or after the end of the incontestability period? Why?

10. The settlement option providing a life income with cash or installment refund seems too good to be true. How can the insurance company agree to pay for as long as the beneficiary-annuitant lives and agree to pay out at least the face amount of the policy?

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. The incontestability clause seems to permit fraud to go unpunished. Do you think that this exception is justified? On what grounds?

2. John Jones dies, leaving $100,000 in life insurance policy proceeds to his widow. Widow Jones elects to have the $100,000 paid out under the life income option. At the end of the first year, after having received $7176 in income, widow Jones is struck by a car and killed. Selection of a straight life income option was a foolish mistake on her part. Discuss.

3. The interest rate guaranteed under the settlement options of a life insurance policy seems low in comparison with alternatives available to the beneficiary. Does the guarantee of 3.5 percent or 4 percent constitute undue enrichment of the insurer at the expense of the beneficiaries?

4. The exposure of insurers to adverse selection is not restricted to the underwriting process. To what extent, if any, is the insurer subject to any form of adverse selection under policy settlement options?

5. On January 1, 2005, Sam Smith gave his application for life insurance to his agent, including his first premium payment. On the application, he neglected to notify the company of a mild heart attack he had suffered eight years earlier. On February 15, he received notification from the company that his application had been accepted. He failed to pay the premium due on January 1, 2007, and on January 30, 2007, he died of a massive coronary infarction. Discuss in detail the liability of the insurance company with reference to specific clauses that apply in this instance.

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Black, Kenneth Black, Jr., Harold D. Skipper, and Kenneth Black III Life and Health Insurance, 14th ed., Lucretian, LLC, 2013

Bruning, Larry, Shanique Hall, and Dimitris Karapiperis. “Low Interest Rates and the Implications on Life Insurers.” CIPR Newsletter, April 2012.

Graves, Edward E. McGill's Life Insurance, 8th ed. Bryn Mawr, Pa.: The American College, 2011.

Skipper, Harold D. and FSA Wayne Tonning The Advisor's Guide to Life Insurance, American Bar Association, 2013.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| American Council of Life Insurance | www.acli.com |

| Life Office Management Association (LOMA) | www.loma.org |

| NAIC InsureU | www.insureU.org |

| Society of Financial Service Professionals | www.financialpro.org |

![]()

1Although the conditional binding receipt is the normal procedure, some companies use a binding receipt that is not conditional. Coverage is effective immediately under interim term insurance, which continues until the contract is issued.

2There are many reasons for the use of care in the designation of the beneficiary. For example, if the insured designates as beneficiary “my wife, Mrs. John Jones,” to whom is he referring? Is this his present or a former wife? Or if he designates “my children” as a class beneficiary, which children does he desire to include? Would adopted or illegitimate children be included? And what about children of a former wife? These difficulties may be avoided with a little care.

3By statute in most states, the incontestable clause must be a provision in all life insurance contracts, and no state permits the period to exceed two years from the date of issue of the contract. Some insurers, perhaps for competitive reasons, have shortened the contestable period to one year, which is permissible under the law. However, courts have generally refused to uphold a provision that makes the contract incontestable from date of issue, particularly in those cases where fraud is involved.

4However, there are a few instances in which fraud would be so abhorrent that impossibility of nullification because of the incontestable clause would be a distinct violation of public policy. For example, courts will permit insurers to deny liability after the contestable period has terminated in those cases in which insurable interest did not exist at the inception of the contract. Liability could also be denied if it is discovered that a healthier person impersonated the applicant in the medical examination, particularly if this person would have been the beneficiary under the policy.

5In years past, the incontestable clause did not contain the language “for two years during the lifetime of the insured.” In a celebrated case, Monahan v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company (283 III. 136, 119 N.E. 68), an insured died during the contestable period and the company denied liability, alleging breach of warranty. The beneficiary, however, waited until the two-year period had expired and then sued the company. The Supreme Court of Illinois held that the policy was incontestable and ordered the insurance company to make payment.

6For rating purposes, life insurers assume that the individual's age changes at the midpoint between birthdays. (Health insurers, in contrast, usually use the applicant's age at his or her last birthday until the next birthday is reached.) Insurers will often agree to backdate a life insurance policy to allow the insured to purchase the coverage at a lower age if the insured pays the premium for the backdated period of coverage. Most state insurance laws limit the period for which a policy may be backdated to not more than six months.

7The question may arise concerning the application of the incontestability clause to the reinstated policy. Is the entire contract subject to contest for two years after the reinstatement, is only the information concerning the reinstatement subject to contest, or is neither applicable? There is some difference of opinion in the courts. However, the majority opinion is that a reinstated contract is contestable for the same period as prescribed in the original contract but only with respect to the information supplied for the reinstatement. Representations in the original application for the policy may not be contested.

8The courts have evolved the doctrine of presumption against suicide, which states that the love of life is sufficient grounds for a presumption against suicide. The burden of proof of suicide is on the company, and the insurance company must prove conclusively the death was a suicide or pay the face of the policy.

9Some states have statutes that impose restrictions on the right of the insurer to avoid liability if the insured commits suicide. In Missouri, for example, the law does not permit any exclusion at all. The insurer can deny liability only if it can prove the insured contemplated suicide at the time the policy was purchased. Needless to say, this intent is difficult, if not impossible, to prove, so insurers in Missouri do not attempt to do so.

10Hazle v. Liberty Life Insurance Company, 186 S.E. 2d 245, 257 S.C. 456 (1972).

11Deaths in past wars have not proved to be catastrophic for insurers. After each of the wars in which the United States has been engaged in the twentieth century, insurance companies found they could cover the deaths that were excluded under the war clause of policies issued and paid the face amount of these policies retroactively.

12Most policies today guarantee interest between 3 percent and 4 percent, but older policies may have higher guarantees. The recent low interest rate environment has reduced the spread between what the insurer earns on its portfolio and the policy guarantees, putting stress on insurer profits.