CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Differentiate between net premiums and gross premiums in life insurance

- Identify the three factors that are used in computing life insurance rates and explain how each enters into the computation

- Describe the nature of a mortality table and explain the nature of the entries for each age

- Describe the net single premium and explain the way it is computed

- Explain the relationship of the net single premium to annual level premiums and describe the way in which annual level premiums are computed

- Explain how the net premium for an annuity is computed

- Distinguish between benefit-certain life insurance contracts and benefit-uncertain contracts and explain the significance of the distinction

In this chapter, we will examine the manner in which the insurance company determines the premiums for the various types of contracts it offers. The purpose here is not to attempt to make the readers competent actuaries. The purpose is to help the reader gain an appreciation of the differences among the various contracts. As we will see, differences in premiums among the various forms reflect the differing probabilities of payment under the policies, the length of time for which protection applies, and the manner in which the premiums are to be paid.

![]()

LIFE INSURANCE PREMIUM COMPUTATION

![]()

There are three primary elements in life insurance ratemaking:

- Mortality

- Interest

- Loading

The first two (i.e., mortality and interest) are used to compute the net premium, which measures only the cost of claims and omits the provision for operating expenses. The net premium plus an expense loading constitute the gross premium, which is the selling price of the contract and the amount the insured pays. For the most part, we will confine our discussion here to the net premium, realizing the premiums we develop are “net” and an additional charge to cover expenses, called the loading, must be added to arrive at the final premium.1

![]()

Mortality

The mortality table is a convenient method of expressing the probabilities of living or dying at any given age. It is a tabular expression of the chance of losing the economic value of the human life. Because the insurance company assumes the individual's risk and since this risk is based on life contingencies, the company must know within reasonable limits how many people will die at each age. Based on past experience and applying the theory of probability, actuaries can predict the number of deaths among a given number of people at some given age.

Tables 13.1 and 13.2 are mortality tables, specifically, the 2001 Commissioners Standard Ordinary tables (2001 CSO tables) for males and females.2 The mortality table is not, as its form might suggest, a history of a group of people from the year they were born until they all died. The information does not come to the actuary in the form shown. The actuary determines the rate of death at each given age (e.g., the number dying per thousand at ages 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on) and, based on this information, builds a table with an arbitrary number of lives at the beginning age. For our purposes, we have started with 100 million lives; this figure, known as the radix, is completely arbitrary. Any number could have been used, for it is the ratio of the number dying to the number living that is important. Tables 13.1 and 13.2 contain five columns each: (1) age; (2) the number living at each age out of the original 100 million; (3) the number of those living at the start of a given year who will die in that year; (4) the ratio of persons dying to persons living expressed as deaths per thousand; and (5) the number of years that those living at any given age can expect, on the average, to live.

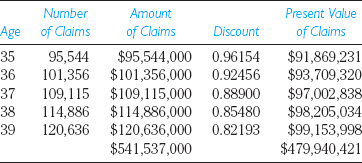

Given the mortality table (the chance of loss), the problem of computing the insurance premium at any given age becomes a matter of simple arithmetic. According to the 2001 CSO table for female lives, for example, out of an initial 100 million females, there are 98,498,982 alive at age 35. Of that number, 95,544 will die before reaching age 36. This represents a death rate of 0.97 per 1000. To insure each of the 98,498,982 members of the group alive at age 35 for $1000 for one year will require $95,544,000 (95,544 times $1000). If we collect $0.97 from each insured (98,498,982 times $0.97), we will have a sufficient fund to pay all claims. The $0.97 represents the net premium (the cost of losses only) that each insured contributed:

![]()

![]()

Interest

Thus far in our computation, we have not considered the factor of interest. All life insurance policies provide for the payment of the premium before the contract goes into effect, but the benefits will not be paid until some time in the future. Because the insurance company collects the premium in advance and does not pay claims until a future date, it has the use of the insured's money, and it must be prepared to pay him or her interest on it. Life insurers collect vast sums of money, and since their obligations mature in the future, they invest this money and earn interest on it. Because they do earn interest on the funds they collect, they do not need to collect the full amount of future losses from the group members. They can collect less than the full amount of the losses, invest it, and then pay the losses out of the total fund of principal and interest. Thus, the present value of a future dollar discussed in Chapter 10 is an important concept in the computation of premiums. To simplify computation, we will assume that all premiums are collected at the beginning of the year and all claims mature at the end of the year. The allowance for interest is made by discounting the future claims to obtain their present value. If we bring the interest into the computation of premiums, the net premium will be something less than would be necessary to charge each insured for his or her cost of the death claims of the group.

TABLE 13.1 2001 Commissioners Standard Ordinary Mortality Table—Male Lives

TABLE 13.2 2001 Commissioners Standard Ordinary Mortality Table—Female Lives

Returning to our example of $1000 worth of insurance for one year for each of the 98,498,982 females alive at age 35, and assuming interest at the rate of 4 percent, the cost of the claims for the group as a whole is $91,869,231 (compared with $95,544,000 without interest).3 If we invest $91,869,231 at 4 percent, it will equal $95,544,000 at the end of one year. The cost per individual becomes $0.9327 or $0.93 ($91,869,231 divided by 98,498,982).

To recapitulate, a one-year term policy at age 35 without interest costs the following:

![]()

A one-year term policy at age 35 with interest costs the following:

![]()

Now, if we want to insure the survivors for another year, we will find that the premium is higher because fewer members are alive to pay the costs, and at the same time the number of deaths will have increased.

At age 36:

![]()

At age 37:

![]()

At age 38:

![]()

At age 39:

![]()

By the time the insureds reach age 65, the mortality table indicates that only 87,165,714 of the original 100,000,000 will be alive and that 1,032,914 of those still alive will die before reaching 66. Thus, the net premium for the one-year term policy at age 65 will be the following:

![]()

Because premiums are based on mortality, they increase as the group of insureds grows older, and as the insureds reach advanced ages, the cost becomes prohibitive. In general, it becomes advisable to level out the cost of protection by charging slightly more during the early years to offset a deficiency during the later ones.

![]()

The Net Single Premium

It is possible to compute a lump-sum payment that if made by the members of the group, will pay all mortality costs over a term longer than one year. The computation of all long-term policies makes use of this concept. The net single premium is a sum that if paid when the policy is issued and if augmented by compound interest, will pay the benefits as they come due. Let us assume, for example, that instead of purchasing insurance annually, our 35-year-old female and the other members of her group wish to purchase a five-year term contract. How much must we charge each individual at the beginning of the five-year policy to permit us to pay the death claims as they mature?

The process of computing the net single premium for a five-year term policy is much the same as that used in computing the annual premium. However, since the charge will be made at the inception of the policy and all claims will not have been paid until the end of the five-year period, the company will have the use of the money for varying lengths of time. To compensate for this, we compute the present value of future claims by discounting the claims due at the end of the first year for one year, those due at the end of the second year for two years, those due at the end of the third year for three years, and so on, throughout the policy term. For example, we know from our previous computation that we need $91,869,231 to meet the $95,544,000 in claims that will mature at the end of the first year. At the end of the second year, we can expect, according to the mortality table, claims in the amount of $101,356,000. Applying the discount factor for two years, we find we will need only $93,709,320 ($101,356,000 × 0.92456) at the beginning of the contract to meet the obligations that will mature in two years. Continuing the process for the full five years, we obtain the present value of all future claims:

During the five-year period, the company will be called on to pay $541,537,000 in death benefits. The present value of these claims is $479,940,421. In other words, $479,940,421 is the amount that will, when invested and with the interest earned on it, permit the company to meet the total obligations during the policy period. This is the cost of claims for the group as a whole. To find the cost of claims for each individual in the group, we divide the present value of future claims by the number of entrants in the group:

![]()

If you add the individual annual premiums ($0.93, $0.99, $1.07, $1.03, $1.18), you will notice the net single premium for a five-year term policy is somewhat less than the summation of the annual premiums for the same five years ($4.87 compared with $5.30). The lower premium for the single-premium contract stems from two facts. First, the insurer has a part of the insured's premium for a longer period when the policy is paid in advance, and the cost is reduced by the greater amount of interest that is earned. Second, in the five-year term policy, all insureds pay their full share of the five-year mortality costs in advance. In the annual premium case, some insureds will die before later premiums become due. In effect, those who die during the early years under the five-year term policy “overpay” their share of the mortality costs, which reduces the cost to the survivors.

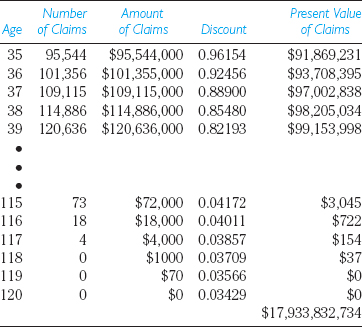

Calculating the net single premium on any of the various policies we have discussed follows the same procedure. In the case of the whole-life policy, for example, all the future claims under the policy are discounted (clear to the end of the mortality table), ending at age 120. A summation of all the present values of future claims divided by the number of entrants at age 35 would give the net single premium for the whole-life policy. In a sense, a whole-life policy is a term policy to age 121 since the premium on the whole-life policy is computed in the same manner as described above. The only difference is in the number of years involved.

If we carry the computation out to the end of the mortality table, using the same technique as in the five-year policy, we obtain the present value of all future claims under a whole-life contract:

The present value of future claims, $17,933, 832,734, represents the amount the insurance company must have to pay all the death claims under the whole-life contract as they occur. Divided by the 98,488,982 entrants at age 35, the net single premium for the whole-life contract is $182.07:

![]()

![]()

The Net Level Premium

The net single premium is the basis for computing the level premium on long-term policies. Although some policies are sold on a single-premium basis, in the event of an early death, the cost of the insurance is high compared with the annual cost. In addition, most people cannot afford the single premium.

To determine the net level premium, we compute the net single premium and convert it to a series of annual payments, considering the premiums that can be expected and the year in which the expected premium will be paid. To do this, we use the concept of the annuity due. Annuities, as we have seen, are concerned with the number of survivors. In computing an annuity due, we ask, What is the current value to the insurance company if each member of the group pays $1.00 for a given number of years while they are still alive? The same principles of mortality and compound interest apply but in a somewhat reverse order. A promise by each of the policyholders alive at age 35 to pay $1 for the next five years will be worth something less than a payment of 98,498,982 times $5. Some entrants will die; in addition, the company will not have the money immediately, so it will lose some interest income on the funds. If we refer to Table 13.2, we find 98,403,438 members of the original group will be alive at age 36 to pay their $1.00. In addition, if we assume a 4 percent rate of return, each dollar paid in one year is worth only about $0.962 today. Every year, fewer members of the group are alive. In addition, the current value of each future $1.00 decreases the longer the time before the dollar must be paid. We can determine the value of $1.00 paid by each policyholder for the next five years as follows:

Thus, if each policyholder alive at age 35 agrees to pay $1 for the next five years, the total has a current value of $455,134,220. To fund the net single premium for the five-year term policy for each policyholder alive at age 35, the insurance company needs $479,940,421 today. Thus, the insurance company needs to collect more than $1 from each policyholder to cover the future claims costs. In fact, the insurance company must collect $1.0545 from each policyholder alive during the next five years:

![]()

To convert the net single premium for a whole-life contract to the annual level premium, we use the same approach, but we use the entire mortality table to age 121. The present value of $1.00 a year for life from each policyholder alive at age 35 is $2,094,693,870. The net single premium for the whole-life policy was $17,933,832,771. Thus, the net level premium is $8.56 per year:

![]()

Computing the premiums for limited-payment (limited-pay) whole-life policies also uses this basic procedure. A limited-pay whole-life policy is the actuarial equivalent of a straight life policy except for the way in which the premiums are paid. To compute the premium for a 20-payment whole-life contract, we begin with the net single premium for a whole-life policy. Under a 20-payment policy, we will spread the premiums over a 20-year period rather than over the total lifetime of the insured. To make the conversion from a net single premium to 20 payments, we compute the present value of payments of $1.00 by those policyholders still alive each year during the next 20 years. That amount is $1,375,298,570. Thus, the net annual premium on a 20-pay whole-life policy is the following:

![]()

The net single premium of $182.07 is mathematically the same as a payment of $13.04 from each of the surviving members of the group for a 20-year period. Each of the premiums for the whole-life policy we have computed is the equivalent of the other two. It makes no difference to the insurer whether the insured makes a net single-premium purchase by paying $182.07, or agrees to pay $13.04 each year for 20 years, or $8.56 each year for as long as he or she lives.

![]()

RESERVES ON LIFE INSURANCE POLICIES

![]()

Under the level premium plan, the insured pays more than the cost of the protection during the early years of the contract. The difference between what the insured pays and the cost of the protection represents the policy reserve. This represents the prepayment of future premiums and is the basis for the cash value.

To illustrate the effect of the prepayment of costs under the level premium plan, Table 13.3 shows the reserve on five one-year term policies beginning at age 35, a five-year term policy on a single-premium basis, and a five-year term policy on a level premium basis. The table indicates the initial reserve and the terminal reserve for each policy for each year. The reserve on a policy at the end of the policy year is known as the terminal reserve, and the terminal reserve at the end of a year plus the net premiums for the next year is known as the initial reserve of that next year. The average of the initial and terminal reserves for any year is called the mean reserve for that year. It is the mean reserve for all active policies that the insurance company is required by law to have on hand at all times.

TABLE 13.3 Policy Reserves—Net Single Premium and Net Level Premium for Five-Year Term Policy and Net Premium for Five Annual Term Policies

As indicated in Table 13.1, under the one-year term option, the premiums collected at the beginning of each year are sufficient with interest income to pay the death claims for the year. When the five-year term policy is purchased on a single-premium basis, a significant reserve is created at inception. Each year, interest is added and death claims are deducted, and the result is the terminal reserve for the year. The reserve gradually diminishes until the final year, when it is just sufficient to pay death claims. Under the level premium option, the reserve increases during the first three years, as the insureds overpay the cost of protection, and then diminishes as death costs exceed premium income and interest in the last two years.

Unlike the reserve on term policies, the reserves on whole-life policies, endowments, and limited-payment whole-life policies do not diminish but continue to accumulate, reaching the face amount of the policy. Because these reserves represent payments by group members that are more than the current cost of the insurance protection, group members have a vested interest in these reserves. In effect, the reserves represent a prepayment for future protection. If an individual decides to withdraw from the group and does not wish the future protection for which he or she has paid, that person is entitled to a return of a portion of his or her premiums. In a sense, the reserve “belongs” to members of the group, and a member who leaves the group is entitled to withdraw a portion of the reserve. Permanent insurance contracts such as whole-life, limited-payment, and endowment policies develop a cash saving fund that is the insured's property. On withdrawing from the group, the insured is entitled to a surrender value based on the policy reserve. Normally, a policy does not develop a cash value until after the second year, and its surrender value rarely equals the full amount of the policy reserve until it has been active for 10 or 15 years. The reserve required for any given policy depends on the insured's age at the issue date, the assumed rate of interest, and the policy type. Since the reserve equals an amount that, together with all future premiums and interest on these premiums and the reserve, will equal future benefits, the lower the amount of future premiums and the higher the amount of future claims, the higher must be the reserve. A simple identity should prove helpful in understanding this relationship:

![]()

A whole-life policy, if continued, will be payable as a death benefit or as an endowment at age 121. The accumulating reserve, which will be required for payment as an endowment at age 121, results in a decreasing amount of risk under the policy. For example, when Mr. X purchases $100,000 of whole-life coverage, he obtains $100,000 of immediate protection. As he pays more into the policy, the cash value accumulates. After 10 years, the policy has a cash value of, say, $30,000. The point that is often overlooked is the actual amount of protection has declined and the insurance amounts to only $70,000. If the insured dies, his beneficiary will collect $100,000, but $30,000 of this amount consists of his investment.4 Under the permanent forms of life insurance, the policyholder does not have $1000 in life insurance protection for each $1000 of face amount but rather, $1000 minus the insured's own accumulated cash value. The actual insurance, or “risk,” of the insurance company is constantly being reduced.

FIGURE 13.1 Reserve accumulation of cash value policies

The major differences among the various forms of cash value life insurance are the rates at which the reserve accumulates. Perhaps these differences and the relationship of the policy reserves under the various contracts can be shown better graphically. Figure 13.1 illustrates the reserve accumulation of various policies purchased by a female insured at age 35. The lines in the chart indicate the accumulation of the policy reserve for a level-premium whole-life contract, a 20-payment life contract, and a policy paid up at age 65. The most important line for our purposes is the one designated net single premium. If the insured purchases a whole-life contract with a net single premium of approximately $108, this amount will be sufficient to equal the face of the policy at age 121. The interest on the net single premium will be credited to the reserve, and together with this interest, the net single premium will be sufficient to pay death claims for the group members and accumulate to the face of the policy at age 121. All the other reserve lines begin at zero, but as the insured overpays the premium, the excess is accumulated as the policy reserve. At any time at which the policy reserve equals the net single premium line, premium payments may be discontinued. Remember, there are no additional premium payments due under the net single-premium contract. So, if the reserve under any other form equals the net single-premium line, interest on that reserve will be sufficient, as in the case of the net single premium, to pay all death claims and still reach $1000 by age 121. Thus, under the 20-payment life policy, the reserve equals the net single premium line at age 55; under paid-up at 65 policy, they are equal at age 65. Thus, other things being equal, the reserve on a 20-payment life and a 30-payment life will be the same at the end of 30 years since the reserve on each policy must by that time be sufficient to pay all future benefits under the policy when credited with interest.5

![]()

BENEFIT-CERTAIN AND BENEFIT-UNCERTAIN CONTRACTS

![]()

Thus far, we have seen that the computation procedure of the premium for all forms of life insurance is similar. The present value of the future claims under the contract is summed, obtaining the net single premium. The net single premium is then distributed over the selected premium payment period, using the concept of an annuity due, which considers interest and survival probability.

The present value of the future benefits under a life insurance contract varies with the probability that the insurer will be required to make payments, which changes with the length of time for which the insurance is to be provided and with the nature of the insurer's promise. If the insurer agrees to pay the policy's face amount if the insured dies within a specified period, as in term insurance, the present value of future benefits will be the individual's share of the discounted death claims that are expected to occur during that period. The longer the period for which the insurance is to be provided, the greater will be the present value of future benefits. Suppose that the insurer agrees to pay the face amount if the insured dies within a specified period and to make payment if he or she survives that period, as in the case of an endowment or whole-life policy. In that case, the present value of future benefits will be the individual's share of the discounted death claims during the period and the discounted value of the endowment benefit. Assuming that the insured persists, the payment of the face of the policy is a certainty.6

All forms of permanent life insurance are benefit-certain contracts. If the insured continues to live, the policy's face amount will be payable, meaning the probability that the insurer will be required to make payment is 100 percent. Term contracts, on the other hand, are benefit-uncertain contracts, in that payment will be made if the insured dies during the policy period. Because the probability of loss under these contracts is less than 100 percent, the present value of future claims is less than that of the present value of future claims under the benefit-certain contracts.

In Chapter 12, we noted that the increasing probability of death at advanced ages makes the cost of insurance at those ages prohibitive. Using the 2001 CSO mortality table and assuming a 4 percent interest rate, the net premium for a one-year term contract of $1000 face amount at age 70 for a female is $17.13. At age 80, it is $42.17, and at age 90, it is $117.23. Few people would be willing to purchase life insurance coverage at these rates, so the level-premium plan was developed to avoid the impact of the increasing mortality.

The level premium contract does not avoid the costs inherent in the higher mortality at advanced ages. The actuarial equivalent of the increasing one-year term rate must be charged even under the level premium plan, but the higher costs are hidden by premium redistribution and the compound interest on the overpayments made during the contract's early years. It makes no difference whether the premiums are paid on an annually increasing basis or if they are leveled out via the level premium; the costs are there. The real secret to the operation of the level premium plan and permanent forms of insurance is the magic of compound interest rather than the law of large numbers. The level premium plan does not avoid the higher mortality costs at advanced ages; instead, it spreads them over a longer period.

Consider the probabilities found in the various forms of life insurance. A young man, age 21, may purchase a term-to-age-65 policy. The probability that he will die and that the insurance company will be required to pay the face amount of the policy is about 16 percent. If he purchased a term-to-age-75 contract, the probability that the company would be required to pay the face of the policy increases to 39 percent. Protection to age 85 involves a probability of 69 percent. What is the probability if he purchases a whole-life or endowment contract? Since the company will inevitably pay the face amount of these policies, the probability is 100 percent.7

At some point, the death “risk” ceases to be a risk. The probability increases each year until the loss becomes a certainty. The exposure under term insurance contracts, on the other hand, is a true contingency, meaning an event that may or may not occur. Mortality costs for the entire life span, that is, to the end of the mortality table, do not constitute an insurable risk. Mortality costs up to age 65, however, represent a reasonable approximation of the insurable risk.

Some question whether insurance covering to the end of the mortality table is a proper application of the insurance mechanism. Insuring under a benefit-certain policy such as a whole-life policy involves the accumulation of an investment rather than a distribution of losses through the law of large numbers. As the insureds under permanent forms of life insurance continue their premium payments, the overpayment piles up and the compound interest on the overpayment accumulates, so that the insureds build up a fund that reduces the risk facing the insurance company. Whereas a rational person would probably refuse to purchase insurance at age 75, or 80, or 85, or 90 on an individual year-to-year basis, this is precisely what the whole-life contract does. However, since the costs associated with the high probabilities can be hidden by the redistribution of premiums and compound interest, the whole-life contract is a salable product, but the high cost is not avoided. The only way in which the cost of death at advancing ages can be avoided is by refusing to purchase coverage against death at advancing ages.

The most intriguing aspect of the distinction between the benefit-certain and the benefit-uncertain contracts is that it illustrates that there is nothing magical or mystical about the insurance equation. The insurance company must collect sufficient premiums to pay the claims it will incur. The benefit-certain contracts are possible only because of the compounding interest on the insured's overpayment of premiums during the early years of the contract.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

net premium

gross premium

mortality tables

loading

annuity due

net single premium

net level premium

terminal reserve

mean reserve

initial reserve

benefit-certain contract

benefit-uncertain contract

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. What are the primary elements in life insurance ratemaking? Which are used in computing net premiums? The gross premium?

2. The insurer must estimate in advance the mortality and the interest that will be earned on policyholders' premiums. How do insurers attempt to guard against deviations from these estimates?

3. The net single premium for a five-year term policy at age 35 is $4.87 (2001 CSO table, female lives, 4 percent interest assumption). Why can we not compute the annual premium for a five-year term policy by dividing $4.87 by 5?

4. Explain what is meant by the term present value. Ignoring the concept of present value, what is the net single premium for a whole-life policy?

5. At age 28, Mr. Jones purchased a whole-life policy, paying the premium in one single payment. On the same day, Mr. Smith bought a 20-pay whole-life policy identical in all other respects to the one Jones purchased. At what point will the reserve on the two policies be equal? Why must they be equal at this point?

6. Under a whole-life policy, the actual amount at risk by the insurance company is constantly decreasing. Explain what is meant by this statement.

7. In a given year, would you expect the initial reserve, the mean reserve, or the terminal reserve of a particular policy to be highest? In your answer, distinguish among the three measures. Which is most significant for regulatory purposes?

8. What is the difference between a policy that is paid up and one that is mature?

9. Briefly explain the distinction between benefit-certain and benefit-uncertain life insurance contracts.

10. You have been called on as a consulting actuary by a tribe of natives in an underdeveloped country. Owing to warfare with the neighboring tribes, the mortality rate in the country is high. At the same time, the interest rate is high. On the basis of the mortality and simplified discount tables given here, compute the following:

- The one-year term rate for ages 21–25

- The net single premium for a five-year term policy at age 21

- The net single premium for a five-year endowment at age 21

- The annual premium for the five-year endowment at age 21

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. An article on life insurance in a midwestern newspaper stated: “It makes good sense to purchase life insurance at an early age since the cost of coverage increases the longer you wait.” Do you agree or disagree with this statement?

2. Assume you have two groups of policies, each consisting of 1000 policies, issued at the same time to groups of the same age. One group consists of single-premium whole-life policies and the other of 20-payment whole-life policies. If mortality is less than anticipated, which group will show the largest mortality savings?

3. “A young man, age 21, may purchase a term-to-age-65 policy. The probability that he will die and the insurance company will be required to pay the face amount of the policy is about 12 percent. If he could purchase a term-to-age-75 contract, the probability the company would be required to pay the face amount of the policy increases to 27 percent. Protection to age 85 involves a probability of 53 percent.” Reflecting on the rules of risk management discussed in Chapter 3, what conclusions can one draw concerning the purchase of benefit-certain contracts?

4. “Other things being equal, the lower the interest assumption used in the computation of the premium, the lower will be the reserve on a policy at any point in time.” Do you agree or disagree? Why?

5. It has been shown that wide differences in cost exist among life insurers for the same type of policy. The three factors used in premium computation are the basis for these differences in cost. To which of the three factors would you attribute the widest differences in cost?

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Black, Kenneth Jr., Harold D. Skipper, and Kenneth Black. III. Life Insurance, 14th ed. Lucretian, LLC, 2013.

Chastain, James J. “The A, B, C's of Life Insurance Rate and Reserve Computation.” Journal of Insurance, vol. 27, no. 4 (Dec. 1960).

Cooper, Robert W. “The Level Premium Concept: A Closer Look.” CLU Journal, vol. 30, no. 2 (April 1976).

Gerber, Hans U. Life Insurance Mathematics. New York, N.Y.: Springer Verlag, 1990.

Harper, Floyd S., and Lewis Workman. Fundamental Mathematics of Life Insurance. Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin, 1970.

Mehr, Robert I., and Sandra G. Gustavson. Life Insurance: Theory and Practice, 4th ed. Austin, Tex.: Business Publications, 1987. Chapters 23–24.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| American Academy of Actuaries | www.actuary.org |

| American Council of Life Insurance | www.acli.com |

| Life Office Management Association (LOMA) | www.loma.org |

| Society of Actuaries | www.soa.org |

![]()

1In reality, the process of setting premiums and reserves for life insurance policies is considerably more complex than presented here. Actuaries will use stochastic models to measure how the policy will perform under a variety of assumptions as to future interest rate scenarios and policyholder lapse rates. The examples are simplified for purposes of illustration.

2The illustrations in this chapter use the 2001 Commissioners Standard Ordinary (CSO) composite mortality table for females. This is one of six tables developed by the Academy of Actuaries and the Society of Actuaries and adopted by the NAIC in December 2002. These tables are referred to as the Commissioners Standard Ordinary Tables because they have been adopted by the NAIC for minimum reserve valuation under ordinary policies. There are three tables for female mortality (smoker, nonsmoker, and composite) and three for male mortality (smoker, nonsmoker, and composite). These tables will replace the 1980 CSO mortality tables for reserve and nonforfeiture valuation purposes. The 2001 CSO tables are derived from the experience of 21 life insurers during the period 1990 to 1995 and reflect increases in life expectancy since the 1980 CSO tables were developed. Consequently, the 2001 CSO tables are expected to produce reserves that are approximately 20 percent less than those produced by the 1980 CSO mortality tables.

3As in the selection of the mortality table, the insurer has freedom in selecting the interest assumption for premium computation. For many years, the interest rate for computing policy reserves was set at 4.5 percent in most states (5.5 percent for single-premium policies). The NAIC's current model valuation law, however, specifies a variable interest assumption for computing policy reserves. The specified rate depends on the lesser of a 36-month or 12-month monthly average of rates earned on seasoned corporate bonds ending June 30 prior to the year of policy issue. The specific formula varies by product type and guaranteed duration of the policy. For 2007, the valuation interest rate for policies with a guaranteed duration of more than 20 years was 4 percent. Because of the long-term nature of life insurance contracts, insurers tend to use conservative interest rate assumptions.

4An alternative approach would be to say that the beneficiary collects $100,000 and that the investment is forfeited to the company. The net effect is the same.

5A policy is paid up when no further premiums are due on it and the reserve is sufficient, with the interest on it, to pay all future claims under the policy. Since

![]()

a policy is paid up when

![]()

6A policy is mature when the face of the policy is payable. Thus, the whole-life policy matures at age 121.

7The probability of death after age 65 is much greater than is the probability of death up to age 65. In fact, the probability of death during the 10-year period from age 65 to age 75 exceeds the probability for the entire period from age 21 to age 65.