CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Identify and describe the major problems associated with the current health care system

- Identify the past efforts that have been made to address the problems associated with the financing of health care in the United States

- Distinguish between the traditional fee-for-service approach to health insurance and the capitation system of managed care providers

- Identify common cost-containment activities that have been adopted by health insurers

- Identify and describe the traditional forms of medical expense insurance, distinguishing between basic policies and major medical insurance

- Explain how managed care and consumer-directed health plans differ in their approach to controlling health care costs

- Describe the key features of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

A well-planned program for financing medical expenses is an important part of any personal risk management plan. Unexpected illnesses and injuries can result in catastrophic medical expenses for the individual and his or her family. In this chapter, we turn to the subject of insurance against the cost of medical expenses.

Medical expense insurance provides for the payment of the medical care costs that result from sickness and injury. It helps meet the expenses of physicians, hospital, nursing, and related services, as well as medications and supplies. Benefits may be in the form of reimbursement of expenses (up to a limit), cash payments, or the direct provision of services. Like disability income and life insurance, medical expense coverage is sold on an individual and a group basis.

Although insurance is an important tool for financing health care expenditures, most health care costs are paid from sources other than private health insurance. In 2011, public sources, including federal, state, and local governments, covered 45 percent of personal health care expenditures.1 The bulk of this (37.8 percent) represented payments for Medicare and Medicaid. Out-of-pocket expenditures covered about 12.1 percent, and miscellaneous programs covered about 7.8 percent. Finally, private insurance, written by various insurers, provided financing for 35.2 percent of personal health care expenditures.

![]()

BACKGROUND ON THE CURRENT HEALTH INSURANCE MARKET

![]()

Before turning to a discussion of health insurance, we will examine the system of health care delivery in this country and the ways in which health care delivery is financed. Both will be useful in understanding some of the coverage features one encounters in the health insurance market.

![]()

Historical Development of Health Insurance in the United States

Health insurance is a phenomenon of the twentieth century. Although accident insurance was first offered in 1863, coverage for expenses associated with sickness did not become popular until after World War I. Interestingly, it was hospitals, not traditional insurance companies, that popularized medical expense coverage. Early in the 1920s, a number of innovative hospitals began to offer hospitalization on a prepaid basis to individuals.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield In 1929, a group of school teachers arranged for Baylor University to provide hospital benefits on a prepaid basis. This plan is considered the forerunner of Blue Cross plans (also called Blues), which were organized by a group of hospitals to permit and encourage prepayment of hospital expenses. They offered subscribers contracts that promised a semiprivate room in a participating hospital when the insured was hospitalized. In 1939, the first Blue Shield plan was organized by physicians in California to offer prepaid surgical expense coverage.

Commercial Insurance Companies In the 1930s, commercial insurance companies began to market hospital and surgical expense insurance. Unlike the Blues, commercial insurers provided coverage on a reimbursement basis, providing payment up to a specified dollar maximum per day, while the insured was confined to a hospital, or providing a specific limit of coverage for various surgical procedures. In 1949, commercial insurers introduced a form of catastrophe medical expense coverage called major medical insurance. When written with basic hospital insurance and surgical expense insurance, this major medical insurance became the standard against which other health insurance plans were measured.

Fee for Service The health insurance provided by Blue Cross and Blue Shield organizations and insurance companies is now referred to as fee-for-service or indemnity coverage. Under this approach, the insured had complete autonomy in the choice of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers. Insureds were free to choose any specialist without getting prior approval, and insurers did not attempt to decide whether the health care services were necessary. Insurers attempted to control costs through deductibles and share-loss provisions called coinsurance, under which the patient was required to bear a part of the cost.

Medicare In 1965, Congress amended the Social Security system by establishing the Medicare program to provide medical expense insurance to persons over age 65. The same legislation created Medicaid, a state-federal medical assistance program for low-income persons. During the years immediately following Medicare in 1965, the cost of health care (and of private health insurance) increased. Attention turned to the problems inherent in the fee-for-service system. Many experts argued that this system provided an incentive to overutilize health care. When the insurer (or government) paid the costs, insureds and providers had no incentive to reduce costs. It was argued the provider stood to gain when more services were provided. Insurers, employers, and public policy makers began to look for ways to change the way in which health care was financed to give providers an incentive to control medical expenses.

Managed Care Organizations The solution was the concept of managed care, which represented a change in the financing of health care and in its delivery as well. New types of “insurers” emerged that offered risk financing and health care. The prototype for this type of organization was the health maintenance organization, which offered a more direct relationship between the provision of health care and its financing.

Health Maintenance Organizations The distinguishing characteristic of a health maintenance organization (HMO) is that the HMO provides for the financing of health care, as do commercial insurers and the Blues, and delivers that care. HMOs often operate their own hospitals and clinics and employ or maintain contracts with physicians and other health care professionals who deliver health care services. The insurance element in the operation of HMOs derives from the manner in which they charge for their services, which is called capitation. Under the capitation approach, subscribers pay an annual fee and in return receive comprehensive health care. The HMO may be sponsored by a group of physicians, a hospital or medical school, an employer, labor union, consumer group, insurance company, or Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans.

Although HMOs have been around for at least as long as the Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, it was not until 1970s that public and government attention was focused on them, bringing them their current popularity.2 In 1971, the federal government adopted a policy of encouraging and promoting HMOs as an alternative to the fee-for-service approach to health care financing. Two years later, Congress passed the Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973, which provided funding for new HMOs and the expansion of existing ones. The law also required employers with 25 or more workers who are subject to the Fair Labor Standards Act to offer, as a part of its health benefit program, the option of membership in a federally qualified HMO if one is available.

HMOs may be organized in a variety of ways. Physicians may be directly employed by the HMO (a staff model HMO) or the HMO may contract with individual physicians or with physician groups. Whatever the arrangement with the physicians, from the subscriber's point of view, the fee-for-service system is replaced by a system of capitation. In return for a fixed monthly fee, the individual receives most medical care required during the year. There may be a nominal charge, on the order of $10, paid by the participant when visiting the physician, but this charge is the same regardless of the service rendered. The subscriber is required to choose a primary care physician (also known as the PCP or gatekeeper), who is responsible for determining what care is received and when the individual is referred to specialists. If the PCP decides the patient requires the services of a specialist, the patient is referred to a specialist in the HMO network. If the network does not include a specialist of the type required, a referral is made to a specialist outside the network. Emergency care services are provided outside the network when there is a sudden onset of an illness or injury that, if not immediately treated, could jeopardize the subscriber's life or health.3

Preferred Provider Organizations Given the successes of HMOs in controlling costs, commercial insurers began to look for ways to copy their success. Noting that many individuals objected to the limitations placed on their ability to select the physicians and hospitals, insurers sought other ways they could reduce costs by contracting with providers while still allowing insureds the option to choose their provider. This led to the development of preferred provider organizations (PPOs). A preferred provider organization is a network of health care providers (doctors and hospitals) with whom an insurance company (or an employer) contracts to provide medical services. The provider typically offers to discount those services and to set up special utilization review programs to control medical expenses. In return, the insurer promises to increase patient volume by encouraging insureds to seek care from preferred providers. The insurer does this by providing higher rates of reimbursement when the care is received from the network. The insured is still permitted to seek care from other providers but will suffer a penalty in the form of increased deductibles and coinsurance.

This arrangement preserves the employee's option to choose a provider outside the network, should he or she desire. When the insured stays in the network, the discounted fees to providers should provide some cost savings although the potential for savings is lower than with an HMO.

Point-of-Service Plans Eventually, some HMOs adopted procedures that made them more like PPOs, using what are known as point-of-service (POS) plans. In one respect, a POS plan operates like a PPO since the employee retains the right to use any provider but will have to pay a higher proportion of the costs when he or she uses a provider outside the network. On the other hand, a POS plan is like an HMO since care received through the network is managed by a PCP. In fact, the first POS plans were created when HMOs allowed their subscribers to use nonnetwork providers. The penalties for using a nonnetwork provider are usually greater than the penalties under a PPO. The use of the gatekeeper approach in POS plans was predicted to provide greater cost control than from a PPO arrangement.

Dominance of Managed Care Collectively, HMOs, PPOs, and POS plans are referred to as managed care plans. Although there are important differences among these plans, greater similarities exist. All managed care plans involve an arrangement between insurers and a selected network of providers, and they offer policyholders significant financial incentives to use the providers in the network. The term managed care is also used to refer to the case management procedures used by most health insurers as cost control measures. Even when indemnity plans are offered, they contain cost-containment features that encourage efficient provision of care.

The dramatic growth in popularity of HMOs, PPOs, and POS plans can be seen by examining the trends in enrollment in recent years. Thirty years ago, 90 percent of insured individuals were covered under traditional fee-for-service plans offered by commercial insurers and Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans. By 2011, according to research by the Kaiser Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, 1 percent of workers insured through their employers were covered by traditional fee-for-service plans, 55 percent of workers were enrolled in PPO plans, 17 percent were in HMO plans, and 10 percent were enrolled in POS plans. The remainder were covered by High Deductible Health Plans (HDHPs), discussed later.

![]()

The Attack on Managed Care

In the 1990s, efforts to control health care costs focused largely on the implementation of managed care. By the late 1990s, however, consumer dissatisfaction with the cost-saving features of managed care programs turned the focus of reformers to the quality of the care being delivered. Critics argued that although the fee-for-service system may provide an incentive to overuse medical care, the managed care approach encouraged plans to deny needed services. Managed care, which was once heralded as the solution that promised affordable health insurance to most Americans, became the target of a consumer backlash.

Efforts by managed care organizations to control utilization and associated costs were accompanied by changes in the traditional relationship between patients and providers. Physicians and hospitals became disenchanted with the discounting arrangements of PPOs and other network organizations. Health care providers complained about the interference of “outsiders” in medical decisions, such as the appropriate hospital stay for a particular illness or procedure. Arbitrary decisions by the claims personnel of insurance companies and third-party administrators became the new crusade for consumer activists. The crusade was fueled by congressional hearings and daytime talk shows, where HMO patients recited horror stories about denial of care by HMOs that resulted in serious injury or death. Newspapers and magazines attacked HMOs over the allegations of bonus payments to physicians for not treating patients and for blocking people from even seeing their doctors. In response, state legislatures enacted “Patient Protection Acts” incorporating a variety of quality of care protections.

With respect to patients' rights, the legislation generally followed the recommendations of an Advisory Commission on Consumer Protection and Quality in Health Care, appointed by President Bill Clinton in 1997. The bills included provisions to ensure adequate provider networks and access to physicians, coverage for services outside the network in case of emergencies, increased information for patients, the elimination of “gag clauses” in contracts between insurers and physicians, and improved appeals processes for patients with complaints, including the right to an external review of a denial of coverage.

![]()

Consumer-Directed Health Care

The premise behind managed care is that given the proper financial incentives, health care providers can be encouraged to deliver care efficiently. In the 1990s, attention began to turn to another option: motivating consumers to purchase health care efficiently. This approach has become known as consumer-directed health care.

Consumer-directed health care encourages consumers to control expenses for medical care by giving them a stake in the expenditures. Under a consumer-directed health plan (CDHP), a High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP) is paired with a tax-sheltered account, typically a Health Savings Account (HSA). Individuals make contributions to the account, and make withdrawals as necessary to cover medical expenses. In effect, individuals become responsible for paying for most routine and smaller medical expenses, and the HDHP covers medical expenses above a large deductible. The first CDHPs used Medical Savings Accounts (MSAs), which were authorized on a pilot basis by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). MSAs are still permitted but have been displaced by HSAs, which were created in 2003. In employer-sponsored plans, the HDHP may be paired with an HSA or with a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA), in which the employer makes funds available to cover additional health care costs.

To be eligible for an HSA, an individual must be covered by an HDHP, defined as a plan with a deductible of at least $1,250 for an individual and $2,500 for a family in 2013. Moreover, the plan must not require the insured to incur annual out-of-pocket expenses (for deductibles and coinsurance) of more than $6,250 for an individual and $12,500 for a family. These amounts will be indexed for inflation in future years. The procedure for establishing an HSA is similar to that for establishing an Individual Retirement Account (IRA). Any insurance company or bank can be an HSA trustee, as well as others approved by the IRS. In 2013, contributions of up to $3,250 for an individual or $6,450 for a family could be made to the HSA. Individuals 55 and older who are covered by an HDHP can make additional catch-up contributions of $1,000 each year until they enroll in Medicare.

Investment earnings in the HSA are not subject to current taxation, and distributions used to pay for qualified medical expenses are not taxed. However, distributions not used for qualified medical expenses are treated as taxable income and are generally subject to an additional 20 percent penalty.4

Consumer-driven health plans have increased in popularity in recent years. In 2012, an estimated 16 percent of employees covered by their employers chose the HDHP option, up from 3 percent in 2006.

The evidence for consumer-driven health care is inconclusive. There is evidence that employees enrolled in CDHPs tend to do more research prior to making health care decisions, have lower costs, and exhibit healthier behaviors. Critics argue this is because healthier employees are more likely to choose HDHPs and that an individual with a chronic disease would cost more and would quickly exhaust his or her savings. As more individuals and employers embrace consumer-driven health care, the impact on cost and quality of care may become clearer.

![]()

THE HEALTH INSURANCE MARKET

![]()

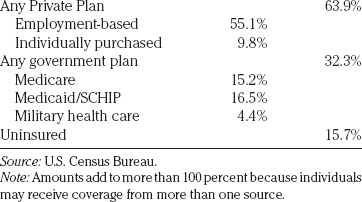

The major sources of health insurance coverage in the U.S. are employers and government programs, as indicated in Table 21.1. Fewer than 10 percent of the population purchases health insurance individually.

![]()

Employer-Provided Health Insurance

The vast majority of those insured in the private sector are covered by group insurance plans, usually sponsored by an employer. In 2011, 58.4 percent of Americans under the age of 65 obtained their health insurance from an employer-sponsored plan.

At least three reasons exist for the overwhelming dominance of employer-provided coverage in this country. The first is historical. Before World War II, few Americans had health insurance. After wage and price controls were instituted during the war, the War Labor Board ruled that the wage freeze did not apply to health insurance benefits. Employers found they could use health insurance as a way to attract workers when they were prohibited from paying higher wages.

A second reason for the prevalence of employer-provided coverage are the advantages of group insurance. The potential for cost savings inherent in the operation of the group mechanism was discussed in Chapter 12. Group insurance provides opportunities for cost savings because of lower underwriting expenses, reduced agents' commissions, and the reduced potential for adverse selection. When the individual is insured as a member of a group, the premium tends to be lower than if the individual had purchased the insurance on his or her own.

TABLE 21.1 Coverage by Type of Health Insurance—2011

Perhaps the most important reason that medical expense insurance is typically provided through an employment relationship is taxes. Contributions made by an employer as payment for health insurance premiums for employees are deductible as a business expense for the employer, but the amount of premiums is not taxable as income to the employee. This means the employee would have to receive something more than the amount of premiums paid by the employer as additional compensation to purchase the same level of benefits. The employee is not taxed on benefits received under such a program if it is reimbursement of incurred medical expenses.5

The coverage in the private sector is provided by several types of insurers, including Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans, HMOs, and commercial insurers. Besides these traditional insurers, the other two important categories are employer self-insured plans and multiple employer welfare arrangements (MEWAs). Generally, the choice of the insurer for such plans rests with the employer, not the employees covered under the plan. This is significant because the objectives of the employer and the employee may differ regarding the scope of coverage and the cost of the plan.

Employer Self-insured Plans The largest group of workers covered by group plans consists of those covered by ERISA-exempted plans—that is, selfinsured plans that are exempt from state regulation. Although the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) primarily focused on retirement plans, it also included a broad preemption of state regulation for employee welfare benefit plans, specifically providing that states may not regulate self-funded health insurance arrangements as insurance. As a result, employers that self-fund the costs of employee health care are exempt from most state laws regulating health insurance. More than two-thirds of large employers are estimated to be self-insured. Employers favor the ERISA preemption of state insurance law because it allows them to avoid state premium taxes (typically 1 to 2 percent of premiums) and the costs associated with state-mandated benefits.

MEWAs Originally, the ERISA exemption from state regulation applied to self-insured plans of a limited number of large employers. Over time, smaller employers have shifted to self-insurance, often as a part of a multiple employer welfare arrangement (MEWA). MEWAs are group programs that provide health and welfare benefits under the ERISA exemption. When Congress enacted the ERISA in 1974, it included a broad preemption of state regulation for employee benefit plans, specifically providing that states may not treat certain self-funded employee benefit arrangements to be insurance. The decision to exempt these plans from state regulation proved ill advised. After a number of MEWA failures, due to the absence of regulatory oversight, the 1982 amendments to ERISA authorized states to regulate self-funded MEWAs. Today, the U.S. Department of Labor and the states have concurrent jurisdiction for regulation of MEWAs. Unfortunately, due to ERISA's complex and confusing provisions, there is still some ambiguity concerning regulatory responsibility for MEWAs. Although MEWAs generally self-insure their members' medical expense exposures, they may also purchase insurance from commercial insurers.

COBRA The importance of employer-sponsored health insurance in the United States is demonstrated by employers being required by federal law to continue offering coverage to their employees and former employees following a qualifying loss of coverage. The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986 (COBRA) requirements apply to employers with group plans covering 20 or more persons and permit continuation when coverage would otherwise end as a result of termination of employment, divorce, legal separation, Medicare eligibility, or the cessation of dependent-child status. The employer must provide the coverage for up to 18 months for terminated employees and up to 36 months for spouses of deceased, divorced, or legally separated employees and for dependent children whose eligibility ceases. Generally, the COBRA participant pays a premium based on the existing group rate. Many states have COBRA-like laws that apply to employers with fewer than 20 employees.

Although employers have played a key role in providing health insurance for many decades, evidence shows a steady decline in the population covered by employer plans in recent years. According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, the percentage of the population under age 65 with employer-provided coverage has fallen from 69.5 percent in 2000 to 58.4 percent in 2011.

One reason for this trend is underlying workforce changes, including increased self-employment, part-time and temporary contract work, and changes in employment across industries and occupations. A second reason is the increase in health insurance premiums, which caused some employers to drop coverage. Other employers increased the required contribution by employees, causing some employees to opt out of coverage. This trend is likely to increase. Many experts have predicted that the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (“the ACA”), also known as Obamacare, will cause additional employers to cease offering health insurance to their employees. This is largely because the ACA mandates the creation of a health insurance exchange in each state, essentially a marketplace where individuals can purchase insurance. The ACA is discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

![]()

The Public Sector

Persons whose health care financing is provided by the government includes those covered by Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children's' Health Insurance Program (CHIP). As the portion of individuals covered by employer-sponsored health insurance has fallen, the number of individuals covered by public programs has grown.

Medicare The Medicare program covers most persons over age 65 and disabled persons who meet specific eligibility requirements. Approximately 60 percent of Medicare-covered persons purchase private insurance to supplement the protection under Medicare. The Medicare program is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 23.

Medicaid Title XIX of the Social Security Act, popularly known as Medicaid, is a federal-state program of medical assistance for needy persons that was enacted simultaneously with the Medicare program. It provides medical assistance to low-income persons and to some individuals who have enough income for basic living expenses but cannot afford to pay for their medical care. States administer the program and make the payments, which the federal government partially reimburses. The federal proportion of the cost is based on a formula tied to state per capita income and varies from about 50 percent to 80 percent, with the poorest states receiving the greatest proportion.

The federal government establishes regulations and minimum standards related to eligibility, benefit coverage, and provider participation and reimbursement. States have options for expanding their programs beyond the minimum standards, subject to federal criteria.

The eligibility requirements for Medicaid are extensive and complex. Federal statutes require state Medicaid programs to cover people who are receiving welfare payments or Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and who meet certain requirements that previously applied to the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). In addition, coverage is provided to certain low-income pregnant women, children under age six, and certain Medicare beneficiaries. As discussed later, the new health reform law is expected to increase the number of individuals covered by Medicaid by providing funding for states to expand coverage up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level.

Medicaid benefits are generally comprehensive. They include the services traditionally included in a commercial group health insurance packet, as well as some services, such as long-term care, that are not. States can require certain recipients to share nominally in their Medicaid coverage cost through premiums, deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, enrollment fees, or other cost-sharing provisions. However, significant cost sharing is prohibitive for recipients and is, therefore, prohibited by federal regulations.

Efforts to control Medicaid costs have led many states to consider reductions or further limitations to covered services. Although a state cannot arbit-rarily deny or reduce the amount, duration, or scope of care because of diagnosis or the type of illness or condition, it can restrict services to those that are medically necessary. States are permitted to incorporate reasonable utilization management provisions in their Medicaid programs. Some states have implemented fairly restrictive limits on the amount, duration, and scope of care without conflicting with the federal requirements.6

State Children's Health Insurance Programs The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA-97) provided federal funding for a new program aimed at insuring children from low-income families who did not qualify for Medicaid. Under the program, states receive federal funding for plans approved by the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). States may provide the coverage by expanding eligibility for Medicaid, by providing insurance under a separate state Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), or by a combination of the two approaches. The federal funds can be used to purchase coverage under group or individual insurance plans. CHIP's design varies by states. States must screen applicants for Medicaid eligibility and ensure Medicaid-eligible children are not enrolled in CHIP. In most states, children under age 19 from families with income up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) are eligible for CHIP coverage. Some states have more restrictive or less restrictive income eligibility requirements however. Furthermore, a few states have received waivers from the federal government to offer coverage to parents of low-income families. CHIP eligibility may not be denied based on preexisting conditions or diagnosis although group health plans may limit services under current law.

Federal TRICARE and CHAMPVA Programs All active and retired military personnel and their dependents are eligible for medical treatment in any Department of Defense (DOD) installation medical facility. In addition, the DOD operates an insurance program called TRICARE. This allows active and retired military personnel and their families to obtain treatment from civilian health care providers. The Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs (CHAMPVA) covers the spouse or child or a veteran who has or had a permanent and total service-connected disability or died in the line of duty.

![]()

THE INSURANCE PRODUCT

![]()

Medical expense policies are not standardized. There are, however, certain benefits common to all policies. For these common benefits, the major difference among plans is the cost percentages paid.

The typical medical expense policy is known as comprehensive major medical expense insurance. In the earlier years, insurers offered different policies covering different classes of benefits: hospital insurance, surgical expense insurance (covering the fees of surgeons), and physicians' expense insurance (covering nonsurgical physicians fees). A major medical policy provides coverage for a broader set of medical expenses, including the traditional coverage for hospital and physician charges and coverage for such things as blood transfusions, prescriptions and drugs, casts, splints, braces and crutches, and durable medical equipment such as artificial limbs or eyes, and even the rental of wheelchairs. Insurance coverage is typically written to cover usual, customary, and reasonable (UCR) charges. This means the insurer will pay the usual fee charged by the provider for the particular service, the customary or prevailing fee in that geographic area, and a reasonable amount based on the circumstances. The UCR standard is a statistically determined value, based on surveys of what doctors and hospitals charge. The UCR level is set at a percentile of what providers charge. For example, if the UCR is set at the 85th percentile, and the UCR for a particular operation is $1,500, this means that 85 percent of the doctors' charge $1,500 or less for the procedure. If the patient undergoes the procedure with one of the 15 percent of doctors who charge more than $1,500, the patient must absorb the difference.

A major medical insurance policy requires the insured to pay a portion of the cost through deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments, and historically had annual and lifetime limits. The federal health reform law (the ACA), discussed later, will have a significant impact on the coverage offered by comprehensive major medical policies. Among other things, the law requires that all policies sold in the individual and small group market must cover a set of ten essential health benefits, and lifetime limits are prohibited for essential health benefits in all policies. Annual limits on essential health benefits are being phased out and will be prohibited for new policies as of 2014.7

The deductible in a major medical policy may be $250, $500, or higher. Most policies make the deductible applicable to a time period, such as a calendar year. Under this form, the deductible applies only once per family member during the stated period. Many policies have individual and maximum family deductibles.

The major medical policy requires the insured to share a part of the loss in excess of the deductible. For example, the insurance company may pay 80 percent of the loss in excess of the deductible, with the insured paying the other 20 percent. This is known as the coinsurance provision. Finally, copayments are the dollar amounts the insured is required to pay for particular services, e.g., each prescription filled or each office visit, regardless of whether the deductible has been met. There is usually a cap on total out-of-pocket costs borne by the insured, commonly $2,000 or $3,000, beyond which the insurance pays 100 percent of covered expenses up to the policy limit. Effective in 2014, the ACA will require all plans to have an out-of-pocket maximum no greater than that allowed for HSA-qualified high deductible health plans.

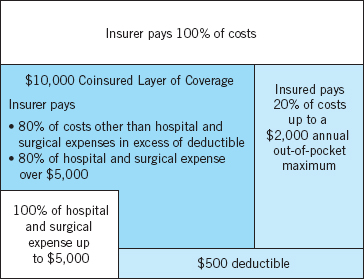

Originally, comprehensive major medical plans applied the deductible and coinsurance provision to all covered medical expenses, including hospital and surgical expense. Current policies may eliminate the deductible or apply a lower deductible to some charges, such as hospital inpatient, doctors office visits, or preventive care. Coinsurance may vary. A sample comprehensive major medical plan is depicted in Figure 21.1.

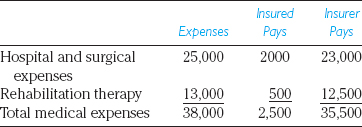

To illustrate the elements in the comprehensive major medical depicted in Figure 21.1 and the operation of major medical policies, generally assume the insured under this program incurs expenses as follows:

FIGURE 21.1 Comprehensive Major Medical

The first $5,000 in hospital and surgical expenses is covered without a deductible and without coinsurance. Expenses in excess of this initial $5,000 are subject to 80 percent coinsurance, up to a $2,000 out-of-pocket maximum. Expenses other than hospital and surgical expense are subject to the $500 deductible and the 80 percent coinsurance provision. Because the insured's share of the hospital and surgical expense above $5,000 satisfies the out-of-pocket maximum on coinsured losses, coverage for the rehabilitation therapy in the example is subject only to the $500 deductible.

![]()

HMO Contracts

In HMO contracts, hospital room and board and in-hospital physicians' medical and surgical services are provided on a fully prepaid basis with no limit on the number of days covered. In addition to these basic benefits, managed care plans often include additional benefits such as preventive care and checkups, well-baby care, and similar health care services. Subscribers are encouraged to have regular medical checkups and see their physician as often as necessary. Outpatient services, such as visits to a doctor's office for diagnostic services, treatment, and preventive care (i.e., routine physical examinations) may be subject to a nominal co-payment charge (e.g., $10 or $15), with no limit on the number of visits. The copayment charge is usually the same regardless of the service rendered. Some HMOs provide prescription benefits as a part of the capitation fee. Prescriptions are usually subject to a $10 or $15 copayment applicable to each 30-day supply of a drug. There is no lifetime maximum dollar limit under the coverage of an HMO.

Nearly all care is provided within the network. The major exceptions are when the primary care physician (PCP) refers the patient to a specialist outside the network or when the subscriber requires emergency services.

![]()

Exclusions under Health Insurance Policies

All health insurance policies are subject to exclusions. Exclusions in individual policies tend to be more extensive than those in group policies, and some group contracts contain more exclusions than others. The following ten exclusions are typical of those in individual or group contracts depending on the insurer.

- Expenses payable under workers compensation or any occupational disease law

- Personal comfort items (e.g., television, telephone, air conditioners)

- Elective cosmetic surgery

- Hearing aids and eyeglasses

- Dental work

- Experimental procedures

- Expenses resulting from self-inflicted injuries

- Expenses resulting from war or any act of war

- Expenses incurred while on active duty with the armed forces

- Services received in any government hospital not making a charge for such services

In addition, most policies contained limitations on preexisting conditions, and maternity benefits were often excluded or limited in individual policies. Coverage for mental health and substance abuse was often limited, particularly in individual policies.

The new essential health benefits requirements will impact the coverage of health insurance policies issued in the small group and individual markets. For examples, starting in 2014, all individual and small group policies must provide coverage for preventive and wellness services, treatment for mental health and substance abuse, maternity care, and pediatric dental and vision care. Preexisting conditions may no longer be excluded.

![]()

Coordination of Benefit

With the increase in numbers of two-income families, situations often arise in which a married couple will be covered under medical expense policies provided by their employers. When an employer-provided policy includes coverage on dependents, one or both partners may be covered under two policies: the policy provided by their own employer and that provided by their spouse's employer.

Insurers developed the coordination of benefits provision to eliminate double payment when two policies exist and to establish a coverage priority for payment of losses. Under a standard coordination of benefits provision, if a wife is covered by her employer and as a dependent under her husband's policy, her policy applies before the husband's policy. The husband's policy pays nothing if the wife's policy covers the total cost of the expenses. Children are covered under the policy of the parent whose birthday is earliest in the year.

![]()

OTHER MEDICAL EXPENSE COVERAGES

![]()

Besides the comprehensive medical expense coverage we have discussed, you should be familiar with several other health contracts. In general, these contracts meet specialized needs or are limited contracts providing coverage for particular losses or losses from specific causes.

![]()

Limited Health Insurance Policies

Some health insurance contracts provide protection only for certain types of accidents or diseases. They are referred to as limited policies and often bear the admonition on the face of the policy, “This is a limited policy. Read the provisions carefully.”

Travel accident policies are a good example of the limited health contract. These policies cover situations if the insured is killed or suffers serious injury while a passenger on a public transportation facility; others provide payment in the event of death from an automobile accident.

The dread-disease policy is an example of a limited sickness policy. This contract provides protection against the expenses connected with certain diseases such as polio, cancer, and meningitis.

In general, limited health insurance contracts are a poor buy. More important, they represent a logical inconsistency and a violation of the principles of risk management. If the individual cannot afford the loss associated with any of the dread diseases covered under such policies, for example, he or she cannot afford the loss associated with other catastrophic illness not covered. Remember, a proper approach to risk management emphasizes the effect of the loss rather than its cause.

![]()

Dental Expense Insurance

Dental expense insurance is a specialized form of health expense coverage, designed to pay for normal dental care as well as damage caused by accidents. Most of the coverage is written on a group basis. It is offered by insurance companies, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield organizations, and dental service corporations, similar in nature to the Blues. The Blues and dental service corporations provide benefits on a service basis. The coverage may be integrated with other medical expense coverage (integrated plans) or it may be written separately from other health care coverages (nonintegrated plans). Dental expense coverage is written on a scheduled or nonscheduled basis. Scheduled plans provide a listing of various dental services, with a specific amount available for each. Unscheduled plans generally pay on a reasonable and customary basis, subject to deductibles and coinsurance.

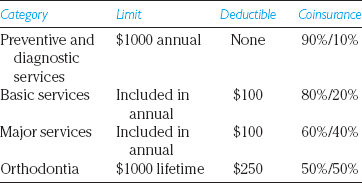

Usually, dental expense insurance distinguishes among several classes of dental expenses and provides somewhat different treatment for each. The coverage is usually subject to a calendar year deductible of $50 or $100 and a coinsurance rate that varies with the service provided. In addition, a dollar maximum per insured person is usually applicable on a calendar-year basis except for orthodontia services, which may be subject to a lifetime maximum. A typical dental insurance plan might provide the following benefits with the indicated limits and coinsurance provisions:

Routine care and preventive maintenance are often covered without a deductible and with a modest coinsurance requirement, such as 10 percent. This part of the coverage includes payment for routine examinations and teeth cleaning once a year, full-mouth X-rays once every three years, and topical fluoride treatments as prescribed. The absence of a deductible and low coinsurance provision is intended to encourage preventive maintenance. Basic services include endodontics, periodontics, and oral surgery, including anesthesia. These services are subject to a higher coinsurance provision and to the annual maximum. Major services include restorative services, such as crowns, bridges, and dentures. These services are subject to higher coinsurance requirements, usually in the range of 60 percent to 40 percent. Ortho-dontic care is subject to a separate maximum and a separate deductible, which may differ from the deductible for restorative care. It is also subject to the highest coinsurance provision, under which the insured may be required to pay 50 percent of the cost of treatment.

![]()

Limited Policies—Prescription Drugs

Prescription drug insurance is a limited form of health insurance designed to cover the cost of drugs and medicines prescribed by a physician. The coverage is written on a group basis, often as an adjunct to other health care coverage. Coverage is written on a reimbursement basis, under which payment is made for the usual and customary charges for covered drugs and prescriptions.

Typically, the insured is required to bear a part of the cost through a coinsurance or deductible. The deductible may be smaller for generic drugs or for drugs on an approved list (known as the drug formulary). Coverage generally excludes contraceptive drugs, dietary supplements, and cosmetics.

The Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 added a new Part D to Medicare, which provides prescription drug benefits to eligible individuals. This benefit is discussed along with other Medicare benefits in Chapter 22.

![]()

HEALTH INSURANCE

![]()

Sometimes, the decisions relating to health insurance coverage of the individual and his or her family are simple: When the employer provides a noncontributory plan; there is no decision to make concerning that coverage. Usually the employee's only concern is whether the program is adequate for the family's needs or if a supplement is needed. Sometimes, when the option is provided, the individual may have to choose between a traditional form of health insurance and membership in a health maintenance organization. Such decisions are generally a matter of personal preference.

In those cases in which the employee must pay part or all of a group plan or when the insurance must be purchased individually, there are several considerations, which complicate the decision.

![]()

First-Dollar Coverages

During recent years, the first-dollar insurance coverages have been increasingly condemned as an improper application of the insurance principle. In the case of health insurance, this criticism may not apply. Because group insurance plans can achieve economies for participants through managed care and participation in a PPO network, the cost of health care acquired through an insurance plan is less expensive than when the same services are purchased by the individual consumer on a fee-for-service basis. For insurance obtained as a part of a large group, administrative fees are modest and can be offset by the reduction in loss costs.

![]()

Taxes and Health Care Costs

The federal tax code complicates decisions regarding the purchase of first-dollar coverages. As noted, employer-paid premiums for employee health insurance are deductible as a business expense by the employer and are not taxable to the employee as income. The employee is not taxed on benefits received under such a program as specified reimbursement of medical expenses incurred.

For the individual, medical insurance premiums receive no special tax treatment. They are considered another medical expense that, combined with other medical costs, is deductible to the extent that the total exceeds 7.5 percent of the individual's adjusted gross income. Since 2003, self-employed persons have been allowed to deduct 100 percent of the cost of health insurance premiums from their gross income.

The deduction is not available to a self-employed person who is eligible to participate in a subsidized health plan maintained by his or her spouse's employer.

![]()

DEFICIENCIES IN THE SYSTEM AND PRIOR REFORM EFFORTS

![]()

Rising costs, inadequate health care services for some of the population, and the failure of past measures to solve the health care problems have contributed to a growing dissatisfaction with the health care financing system. Critics point out that although U.S. medical research in most fields is the most advanced in the world and although many of our hospitals are the best equipped in the world, the United States has been slipping behind other nations in key indexes of national health. These critics argue that other countries spend a smaller percentage of their gross national product (GNP) on health services than our 18 percent and that in return they get better medical care, lower infant mortality rates, and longer life expectancies, with fewer people dying in their productive years.8 Although the problems are manifest in many ways, the U.S. health care system faces two main ones: access to health care and the high cost of health care.

Access to Health Care A part of the dissatisfaction with the present system results from the uneven distribution of health care. Approximately 48.6 million Americans had no health insurance in 2011. Individuals may be uninsured for many reasons, but the most important reason is affordability. Thirty-eight percent of the uninsured are in families with income below the federal poverty level; 90 percent have incomes below 400 percent of the federal poverty level. Many of the uninsured are employed; more than three-quarters are workers or dependents of workers, many working for small employers. The age group most likely to be uninsured are those from ages 19 to 34, where over one-quarter do not have insurance. Approximately 25 percent of the uninsured are currently eligible for public health insurance coverage (e.g., Medicaid or SCHIP) but have not enrolled. For some, being uninsured is a temporary condition, but more than 70 percent have gone without health insurance for over a year.

The problem of access is not limited to the economically disadvantaged. It also exists for persons who, because of personal hazards, are unable to obtain health insurance in the standard market. Persons who must purchase insurance individually sometimes find that it comes with a higher premium and more coverage limits. However, studies show that only 3 percent of individuals applying for insurance are offered coverage with riders limiting coverage and extra premiums.9 Many states have state high-risk pools that offer insurance at subsidized rates to these individuals, and the ACA created a federal Preexisting Condition Insurance Plan to provide coverage until other reforms come into existence in 2014. The ACA provided $5 billion to fund the PCIP, which was expected to cover almost 400,000 people. Costs exceeded expectations, however, and in February 2013, the plan suspended accepting new applicants when it ran low on funds. Approximately 100,000 people were covered by the PCIP.

High Cost of Health Care Ensuring access to health care for the poor is only part of the problem. For insured and uninsured persons, the most distressing problem is cost, meaning the absolute level of health care costs and their yearly escalation. National expenditures for health care, as a percentage of GDP, have increased from 4.4 percent in 1950 to over nearly 18 percent by 2011. Often, employees are unaware of the full cost of the coverage employers are providing. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, the average annual premium for employer-sponsored insurance in 2012 was $5,615 for single coverage and $15,745 for family coverage.

For consumers, the increases in health care costs have come in two ways. The first is the annual increase in premiums, which at times in the past has been 15 percent to nearly 20 percent a year. A second increase in costs has come in the form of increased deductibles and cost-sharing features adopted by employers. Although these measures reduce the employer's cost, the reduction is achieved by shifting the cost to employees.

The increasing health care cost is due to many causes. These include an aging population, improved technology, excess capacity, and defensive medicine. In addition, the use of insurance tends to worsen some problems.

The Aging Population One factor that contributes to increasing health care costs is our aging population. People are living longer and in doing so incur increased health care costs. Older persons tend to experience a more frequent and costly need for medical services. The Medicare system made access available to the elderly but, in doing so, has acted as a cost driver.

Improved Medical Technology By far the greatest cause of escalating health care costs is the high cost of medical technology and the advances in medical knowledge. Medicine is learning new procedures, but seldom does the new medical miracle save money over the old treatment method. Human organ transplants such as of the heart, liver, and kidney have become more common, and their enormous cost intensifies the problems of financing health care.

Excessive Capacity Although advances in medical technology create justifiable increases in cost, they can be a source of waste and inefficiency. When new technology comes onto the market, it tends to spread rapidly throughout the medical community. Once an expensive instrument is purchased, the incentive to use it to recoup the investment, combined with the desire to improve medical care, work to increase health care costs.

Defensive Medicine The increasingly litigious atmosphere in the country, evidenced by an epidemic of malpractice suits, encourages physicians to practice “defensive medicine,” an inclination that compounds the impact of technology on costs. Advances in technology create increasingly expensive testing equipment with vastly expanded diagnostic powers; the threat of malpractice suits strengthens the physician's inclination to use the equipment to perform more and higher-cost diagnostic testing. Patients rarely object to more testing, especially if it is covered by insurance because it might do them some good even if it is not cost effective for society.

Insurance as a Complicating Factor Despite the varied causes of the problems in the health care financing system, the insurance mechanism has become a focal point in the debate. Based on what we know about how insurance operates, this was probably inevitable. The health care financing problem is brought into focus and perhaps worsened by the ways in which insurance operates to spread risk.

Insurance-Encouraged Utilization Medical expense insurance tends to increase utilization of health care services because it alters the cost barriers for consumers. Individuals who have full coverage face a price of zero at the time health care service is delivered. When deductibles and coinsurance exist, they pay some price, but not the service's full cost. People tend to use more health care when someone else is paying the cost. Although the problem is less pronounced in managed care plans than in fee-for-service plans, it is pervasive.

Segmentation and Adverse Selection Another problem with a free, competitive health insurance market is the tendency toward risk segmentation: the classification of insureds into groups that reflect their hazards. This is a problem because of the highly skewed distribution of health expenditures. The most expensive 1 percent of our population account for 22 percent of all health spending, and the top 5 percent account for nearly 50 percent of spending. Half the population spend little or nothing on health care.10

In a private insurance market, competitors have incentives to identify and compete for insureds with lower than average expected losses, which they do by offering these insureds lower premiums. This inevitably results in market segmentation. In every insured group, some individuals' predictable losses are less than the group average. These better-than-average insureds are those who are most likely to be attracted to a competing insurer whose rates better reflect their hazard. When the better-than-average insureds are removed from a group, the average loss of the remaining population increases. Whereas risk segmentation of the insurance market provides benefits for low-risk populations, higher risk populations may find it prohibitively expensive or impossible to obtain insurance for themselves or their families.

The distribution of health costs across the population also suggests a significant potential for adverse selection. Some people have an incentive not to buy insurance because they have lower than average expected loss costs. The problem with this is that today's healthy person may be tomorrow's sick person. Those who do not feel they need health insurance change their minds after the onset of a serious illness and would then like to join the mechanism that spreads the high cost of health care.

Prior Insurance Market Reforms Historically, insurers could refuse to issue coverage to groups or individuals based on their past health care use or general indicators of their health status. Insurers could refuse to renew policies based on previous years' claims experiences and could deny coverage for preexisting illnesses or conditions. In response to the problems encountered by insurance buyers, there have been continuing attempts to reform the market in ways that will make insurance available to those who have difficulty in obtaining it. These efforts have generally taken the form of restrictions on the ability of insurers to select from among prospective buyers. These reforms, which tend to be grouped together in reform proposals are guaranteed issue, renewability, portability, limits on preexisting condition exclusions, and mandated benefits. Guaranteed issue is a requirement that insurers sell health insurance to any eligible party that agrees to pay the applicable premiums and to fulfill the other plan requirements. It can be thought of as a “take all-comers” rule. Guaranteed issue does not regulate the premium charged to a given individual or group although the provision is often accompanied by regulations that restrict rates, limiting the additional amount that can be charged for health status.

Guaranteed renewability ensures that those currently insured cannot have their coverage discontinued by their insurer in a subsequent year as long as the insurer continues to do business in that particular market. As with the guaranteed-issue, guaranteed renewability alone does not limit the premium that can be charged a covered group or individual. Preexisting condition exclusions disallow coverage related to any previous conditions. Without such restrictions, no incentive would exist to purchase insurance until the onset of an illness or injury. Recognizing that a complete elimination of preexisting conditions exclusions would create chaos, prior reforms generally limited the time for which pre-existing conditions could be excluded, usually for 6 to 12 months.

Portability refers to the ability to change insurers without encountering a coverage gap. Reforms relating to portability take the form of limits on preexisting condition exclusions. Under the some prior reforms, individuals maintaining continuous coverage were exempt from all preexisting condition exclusions applying to new policies. The objective of such a rule is to decrease the problem of “job-lock,” the limit on worker mobility resulting from the potential insurance coverage loss if the worker changes jobs.

Mandated benefits are an attempt to guarantee that particular health services are covered in every insurance product sold in a state. The rationale for mandating particular benefits is to avoid segmentation of persons who are subject to the illness or mandated medical needs and, thereby, spread the treatment cost. Mandated benefits include inpatient alcohol and drug abuse programs, infertility treatment, mental health coverage, and chiro-practor and podiatrist services. Mandated benefits provisions, by forcing coverage of particular services, have the potential for spreading risk. Mandated benefits may increase the incentives for insurers to select risks, worsening the degree of risk segmentation as insurers attempt to cover those who are least likely to need the mandated benefits.

During the early 1990s, many states passed “small-group reform” laws, which applied to plans ranging from 1 to 100 lives, depending on the state. These laws included provisions related to guaranteed renewability, guaranteed issue, limits on preexisting conditions exclusions, and rating restrictions.

In 1996, the federal government enacted the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Although most states had enacted small-group and individual insurance reforms similar to those in HIPAA, HIPAA was significant because, for the first time, minimum federal standards were enacted for all plans nationally, including self-insured plans. HIPAA imposed reforms on the large-group market (employers with more than 50 employees), the small group market (employers with 2 to 50 employees), and the individual market.

HIPAA reforms in the group market (large and small) included guaranteed renewability, limitations on preexisting conditions, and portability. Preexisting conditions (defined as a medical condition diagnosed or treated within the previous six months) could not be excluded for more than 12 months and credit toward satisfying the exclusion had to be granted for prior coverage (with no gap greater than 63 days).

In the small-group market (2 to 50 employees), insurers were required to provide all products on a guaranteed-issue basis and could not single out individuals in the group to be charged higher premiums or excluded from coverage. Insurers could use underwriting requirements such as minimum employee enrollment or minimum employer contribution levels. In the individual market, policies had to be guaranteed renewable. Also, certain eligible individuals had guaranteed access to coverage in the individual market. An eligible individual is a person who has at least 18 months of prior health insurance coverage, with the most recent coverage being employer-provided and no break in coverage greater than 63 days.11

While the HIPAA reforms addressed some problems in the health insurance market, many problems remained. Individuals insured in the individual market, as opposed to having employer-sponsored health insurance, were at risk if their health deteriorated. HIPAA prevented insurers from nonrenewing individual coverage unless they exited the market completely, but premiums could increase dramatically if the insured found himself or herself in a “closed block.” In a closed block, the insurer no longer issues new business in that pool of policies. Without healthy new entrants, the overall experience of the block deteriorates and premiums increase. Healthy individuals seek coverage elsewhere, leading to further deterioration in the block's experience. Eventually, the rates skyrocket as the closed block goes into what is known as a “death spiral.” The combination of an increasing uninsured population and individual market rate increases led to a continued search for solutions.

![]()

THE PATIENT PROTECTION AND AFFORDABLE CARE ACT OF 2010 (THE ACA)

![]()

In March 2010, President Obama signed the most comprehensive and controversial health reform law ever enacted in the United States. Also known as Obamacare, the 2700-page ACA is primarily aimed at expanding insurance coverage. During the decade prior to the passage of the ACA, numerous proposals were made to expand coverage and/or control costs. Proposals generally tended to fall in one of three categories: (1) an employer mandate, in which all employers are required to offer coverage, (2) an individual mandate, in which all individuals are required to purchase their own coverage, and (3) a single player plan, in which a universal system of comprehensive health insurance would be funded by taxes and administered by the federal government. The ACA borrows from all three concepts.

The ACA expands insurance coverage by increasing funding for Medicaid, creating a new mandate for individuals to purchase health insurance and offering subsidies to low-income individuals, penalizing large employers who fail to provide coverage to their employees, and subsidizing health insurance provided by small employers. In addition, the law requires the creation of health insurance exchanges in each state to make it easier for individuals and small businesses to purchase health insurance. The law also imposes new regulations on the health insurance market, including eliminating preexisting conditions and maximum coverage limits. Most of the provisions of the ACA will become effective in 2014, but some were phased in earlier.

The ACA is too far-reaching and complex to describe in detail here, but providing a summary of key provisions is useful.

Medicaid Expansion The ACA provides funding for the states to expand Medicaid coverage to nearly all individuals under age 65 with incomes below 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), or about $33,000 for a family of four. States may opt out of the expansion, but the federal government will fund 100 percent of the additional benefits from 2014 through 2016. After 2016, the federal share decreases until it reaches 90 percent for 2020 and later years. Some states have raised concerns about their ability to continue to fund the expansion when federal contributions decrease, and are concerned that Medicaid's “maintenance of effort” requirements will prohibit their cutting benefits in the future. (Under the Medicaid “maintenance of effort” requirements, states that reduce program eligibility or increase premiums can lose all federal Medicaid funding.) As of. June 2013, 26 states and the District of Columbia had indicated they would participate, 13 states had rejected participation, four were pursuing an alternative model, and the remaining seven were undecided

Individual Mandate Beginning in 2014, U.S. citizens and legal residents must have “qualifying health coverage.” The qualifying coverage requirement may be met by obtaining coverage from an employer, purchasing individual coverage, or participating in a governmental program, such as Medicare or Medicaid. Those without coverage pay a penalty of the greater of $695 per year for an individual to a maximum of $2,085 per family or 2.5 percent of household income. This penalty is phased in over three years and is lower in 2014 and 2015. After 2016, the dollar amount of the penalties will be increased for inflation. The individual mandate has several exemptions, including individuals for whom the lowest cost plan option exceeds 8 percent of the individual's income and those with incomes below the federal tax filing threshold.12

Subsidies to Individuals Effective January 1, 2014, the ACA provides premium credits and cost-sharing subsidies to U.S. citizens and legal immigrants with incomes between 100 and 400 percent of the federal poverty level. (To illustrate, this would have been between $23,550 and $94,200 for a family of 4 in 2013). At 100 percent of FPL, the premium credit is such that the individual's share of the premium does not exceed 2 percent of income. Credits decrease according to a sliding scale. From 300 to 400 percent of FPL, the credit is set to limit premiums to 9.5 percent of income. Cost-sharing subsidies assist in covering deductibles and coinsurance, again according to a sliding scale. Credits and subsidies are only available for insurance purchased on an exchange, and employees are ineligible if they are offered coverage by an employer unless that coverage fails to meet minimum standards or the employee share of the premium exceeds 9.5 percent of income.

Large Employer Penalties An employer with 50 or more full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) will be assessed a penalty if one or more of its employees receives the premium tax credit described above. Any employee who works at least 30 hours per week is considered full-time. In addition, hours worked by part-time employees must be included at the rate of one FTE per 120 work hours per month. The ACA specifies an effective date of January 1, 2014, for the large employer mandate, but in July 2013, the Obama administration announced it would delay implementation until January 2015.

The amount of the penalty depends on whether the employer offered coverage to the employee. If the employer did not offer coverage, the penalty is $2,000 per full-time employee, excluding the first 30 employees. If the employer offered coverage, but an employee qualified for and took advantage of the tax credit, the employer must pay the lesser of $3,000 for each employee receiving a premium credit or $2,000 for each full-time employee, excluding the first 30 employees. Part-time employees (those working fewer than 30 hours per week) are not included in the penalty calculation, and some large employers have reportedly reduced employee work hours to avoid the penalty.

Finally, employers with more than 200 employees must automatically enroll employees into the health insurance plan, although employees may opt out of coverage.

Small Employer Tax Credit Employers with 25 or fewer employees and average annual wages of less than $50,000 may be eligible for a tax credit if they purchase health insurance for their employees. To qualify, the employer must contribute at least 50 percent of the total premium cost or 50 percent of a benchmark premium. Beginning in 2014, the maximum tax credit is 50 percent of the employer's contribution to health insurance for for-profit employers and 35 percent for non-profit employers, and the $50,000 wage limit will be indexed for inflation.13 The credit is based on a sliding scale and decreases as firm size and average wage increase, with the maximum credit available to employers with 10 full-time employees and average annual wages of $25,000.

Health Insurance Exchanges A key feature of the ACA is the creation of state-based health insurance exchanges for individuals and small employers. The exchanges will serve as an electronic market-place for individuals and small businesses to purchase insurance. They will determine eligibility for Medicaid, CHIP, premium tax credits, and cost-sharing subsidies. Individuals must purchase their insurance on an exchange to receive the tax credits and subsidies.

The ACA requires states to create a separate exchange for individuals and for small businesses (defined as having up to 100 employees) and to have them operational by January 1, 2014.14 Exchange enrollment is scheduled to begin on October 1, 2013. A state may create more than one of each so long as they operate in distinct geographic areas.

Exchanges will contract with qualified health insurance companies, provide consumer outreach and assistance, use a streamlined application form that will determine whether the individual is eligible for Medicaid, CHIP, premium tax credits, or cost-sharing subsidies, and provide consumer information to help individuals compare plans. If the applicant is eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, he or she may be enrolled automatically. Exchanges will operate a risk adjustment program so insurers who get a disproportionate share of high-risk individuals can be compensated by other insurers.

A state may choose from among three options for its exchange. First, the state may establish its own exchanges meeting the requirements established by the federal U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Second, the state may choose to partner with HHS, with the state performing some functions and HHS performing others. Finally, for states that fail to establish a state-based or state-federal partnership exchange, HHS will operate a federally facilitated exchange.

There are various ways to design the exchanges. One key decision is which insurers are allowed to participate on the exchange. In some states, the exchange may use selective contracting, inviting insurers to made bids and selecting those it determines offer the best value to consumers. In other cases, the exchange may allow any qualified plan to market on the exchange. HHS has indicated the federally facilitated exchange will adopt the latter model, permitting any health plan that is qualified to market on the exchange.

As of May 2013, 27 states had defaulted to the federal exchange, seven states were planning to partner with the federal government, and sixteen states and the District of Columbia had opted to do full state-based exchanges.

In designing the exchanges, policymakers were concerned there might be adverse selection between policies written on and off the exchange. That is, they worried that less healthy individuals might gravitate toward the exchange, while healthier people purchased their coverage outside the exchange. This could result in premiums being higher on the exchange. To prevent this outcome, the ACA requires insurers to pool their experience in both markets when setting rates. There are separate pools for individual and small-group business. Plans that existed when the ACA was enacted (grandfathered plans) are exempt from the pooling requirement, as long as they don't make major changes in policy features.

Qualified Health Plans Qualified Health Plans (QHPs) provide coverage for mandated benefits known as essential health benefits. Essential health benefits must include items and services within at least the following 10 categories: ambulatory patient services; emergency services; hospitalization; maternity and newborn care; mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment; prescription drugs; rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices; laboratory services; preventive and wellness services and chronic disease management; and pediatric services, including oral and vision care.

Insurance policies in the small-group and individual market, except for grandfathered plans, must cover these essential benefits, as must all state Medicaid plans. Deductibles and copayments may vary across plans, but the out-of-pocket maximum expenditures for the consumer may not be greater than the out-of-pocket maximum for HSA-qualified HDHPs ($6250 for an individual and $12,500 for a family in 2013).15

The ACA defines a set of four standard “metallic” levels for policies, based on their actuarial value. The plan's actuarial value is the percentage of covered health care costs the plan expects to pay for the broad population. The four standard categories and their actuarial values are the following: bronze plans (60 percent), silver plans (70 percent), gold plans (80 percent), and platinum plans (90 percent). For example, the gold plan pays on average 80 percent of the covered benefits cost, while the individual pays the remaining 20 percent through copayments and deductibles.16 Greater standardization of benefits is intended to facilitate comparison by consumers and make the purchase of health insurance easier. In addition to the plans mentioned above, a catastrophic limited-coverage plan may be offered to individuals under the age of 30 or those exempt from the individual mandate because of income.

Insurance Market Reforms The ACA imposed new requirements on health insurers and health insurance policies. Although most are not effective until 2014, a number of reforms became effective more quickly. Beginning September 23, 2010, policies could not include lifetime limits on the dollar value of essential benefits, and annual limits were capped for nongrandfathered plans. Insurers were required to cover certain preventive care. Plans were required to provide coverage for dependent children under age 26 and could not impose preexisting conditions exclusions on children under age 19.17

Major reforms become effective in 2014. That is when the exchanges begin providing insurance, small-group and individual policies must cover essential health benefits, and plans are standardized into the four “metal” categories (bronze, silver, gold, and platinum). All individual and group insurance plans must be guaranteed issue and guaranteed renewable, and preexisting conditions exclusions are prohibited. Nongrandfathered plans may not impose annual dollar limits on essential health benefits. Insurers are still permitted to use the underwriting requirements, such as minimum employee participation and minimum employer contributions, that were permitted under HIPAA. Some provisions are designed to put downward pressure on insurance rates by monitoring and controlling the premium amount that goes to pay for health services, as opposed to administrative costs or profit. Insurers must report the portion of premiums they spend on paying claims and on efforts to improve health quality, a number known as the loss ratio.18

New rate regulation will limit the factors used by insurers to set premiums. Premiums will only be allowed to vary by family structure, geography, actuarial value, tobacco use, age, and participation in health improvement programs. Variation for age is limited to 3 to 1, that is, a 64-year-old individual may only be charged three times more than a 21-year-old individual. (Today, most states allow a difference of at least 5 to 1.) States may be more restrictive in their rate regulation, but they may not be less restrictive.

Efforts aimed at controlling costs and improving quality Most of the ACA provisions aimed at controlling increasing health care costs focus on Medicare and are discussed in Chapter 23. HHS is given authority to undertake a series of pilot programs in health care delivery and organization that can be expanded if successful. The law creates two new research bodies to recommend ways to control costs: the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The law also provides funding for efforts to prevent chronic disease and improve public health.

Criticisms of the ACA The Administrative Care Act is among the most controversial pieces of legislation the federal government has ever enacted. While not uniform, attitudes toward the reforms generally fall along partisan lines. In fact, the bill passed the Congress without a single Republican vote in the House or Senate. Attitudes toward the reforms in the states largely mirror these early partisan battles. States rejecting the Medicaid expansion are largely governed by Republicans, while Democratic governors are more likely to invest in the creation of state-based exchanges.