CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Explain the nature of insurance company reserves

- Explain the effect of statutory accounting requirements on the indicated profitability of insurers

- Describe the types of reinsurance and discuss the purposes of reinsurance

- Describe the ways in which insurance companies are taxed

In a general sense, the financial statements of insurance companies are similar to those of other business firms. However, state regulations require certain modifications of the traditional accounting practices in insurance accounting. These changes can distort the financial statements of insurers if they are not recognized. This chapter points out a few of the major differences between insurance accounting and accounting practices in other businesses and relates the implications of these differences to the financial operations of insurers.

![]()

STATUTORY ACCOUNTING REQUIREMENTS

![]()

The set of accounting procedures embraced by insurance regulators is referred to as the statutory accounting system because it is required by the statutes of the various states. Nearly all insurance company accounting is geared to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) Annual Statement Blank, which is a standardized reporting format developed by the NAIC. In it, each company must file an annual statement with the insurance department of its home state and with every other state in which it is licensed to do business. With minor exceptions, the required information and the manner in which it is to be submitted are the same for all states. The Annual Statement Blank has two main versions: one for property and liability insurers and one for life insurers. The information required in these documents and the procedures for recording that information (which are also spelled out by the NAIC) set the ground rules for insurance accounting.

Basically, the statutory system is a combination of a cash and an accrual method and differs from generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) in a number of ways. Because the principal emphasis in statutory accounting is on reflecting the ability of the insurer to fulfill its obligations under the contracts it issues, statutory accounting is, in many areas, ultraconservative.

![]()

Differences Between Statutory Accounting and GAAP

Before examining the specific requirements of statutory accounting and its applications to property and liability and life insurers, it may be helpful to note some of the areas in which statutory accounting differs from GAAP. Because these differences apply to the life field and the property and liability field, a brief overview will eliminate the need for repetition in the following discussion.

Admitted and Nonadmitted Assets The first difference between GAAP and statutory accounting lies in the criteria for inclusion of assets in the balance sheet. Although most noninsurance companies recognize all assets, insurance companies recognize only those that are readily convertible into cash. These are called admitted assets, and only they are included in the balance sheet of an insurance company. Assets such as supplies, furniture and fixtures, office machines and equipment, and premiums past due 90 days or more are nonadmitted assets and do not appear on the balance sheet. The elimination of these nonadmitted assets, whose liquidity is questionable, tends to understate the equity section of the balance sheet.1

Valuation of Assets For many years, GAAP required insurer assets to be valued on balance sheets at the lower of cost or market value or, in the case of debt securities (e.g., mortgages and bonds), at amortized value. The use of amortized value for debt securities was justified on the assumption that insurers would hold the investments to maturity, and therefore, changes in market value prior to maturity were unimportant. In reality, insurers did not hold all assets to maturity. In 1993, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued Statement No. 115, Accounting for Certain Investments in Debt and Equity Securities, which changed the reporting of many insurer assets on GAAP financial statements.2 This standard affects GAAP accounting for marketable equity securities and all debt securities. The standard requires companies to classify securities as held to maturity, trading, or available for sale. Only assets in the held-to-maturity category may be valued at amortized cost. The held-to-maturity category is limited to debt securities (e.g., bonds and mortgages) that the company has both a positive intent and ability to hold to maturity. Securities in the other two categories are carried at fair market value.

Under the statutory system, stocks are carried at market value, as determined by the NAIC Valuation of Securities Task Force based on market values at the end of the year. Bonds not in default of interest or principal payments are carried at their amortized value.3 (Bonds in default are carried at market value.) This means that changes in the market value of stocks held by insurers directly influence the equity section of the balance sheet, whereas changes in the market value of bonds do not. Unrealized capital gains or losses on stocks under the statutory system are reported directly as changes in equity but are not realized until the sale is made.4

Matching of Revenues and Expenses A final major difference between statutory accounting and GAAP is in the matching of revenues and expenses. Under GAAP, revenues and expenses are matched, with prepaid expenses deferred and charged to operations when the income produced as a result of incurring those expenses is recognized. Under statutory accounting, all expenses of acquiring a premium are charged against revenue when they are incurred, rather than being treated as prepaid expenses that are capitalized and amortized. The revenue generated, on the other hand, is treated as income only with the passing of the time for which protection is being provided. In the property and liability field, for example, commissions are generally payable when the policy is issued, and such expenses are charged against income at the time they are incurred. The related premium income, however, is deferred, and equal portions corresponding to the protection provided over time are recognized only as that time passes. Thus, whereas revenue is deferred until earned under the statutory system, there is no similar provision for the deferral of prepaid expenses; revenue is accounted for on an accrual basis, while expenses are accounted for on a cash basis. GAAP would dictate that the revenue and the expenses related to the acquisition of that revenue be deferred and amortized over the life of the policy.

Other Differences In addition to the three major distinctions outlined, there are other differences between statutory accounting and GAAP. However, those noted are the principal differences and the ones that create the greatest distortions in the financial statements of insurers.

![]()

Terminology

Along with the differences in conventions, insurance accounting and finance have their own established terminology. Some of the specialized terminology will be dealt with later, but there are two important concepts that should be established at the outset. One is policyholder's surplus, and the other is reserves.

Policyholder's Surplus The equity section of the balance sheet for any business consists of the excess of asset values over the liabilities of the firm. For an insurance company, it consists of one or two items. In the case of stock companies, it consists of the capital stock, which represents the value of the original contributions of the stockholders, plus surplus, which represents amounts paid in by the organizers in excess of the par value of the stock and any retained earnings of the company. Because there is no capital stock in mutual insurance companies, the total of the equity section is called surplus. In stock and mutual companies, this total is referred to as policyholders' surplus, indicating this is the amount available, over and above the liabilities, to meet obligations to the company's policyholders.5

Reserves The major liabilities of insurance companies are debts to policyholders; they are called reserves. In insurance accounting and insurance terminology generally, the term reserve is synonymous with liability. Understanding insurance company finances will be simplified if this point is clear.6

![]()

PROPERTY AND LIABILITY INSURERS

![]()

We will begin our discussion of the financial aspects of the operations of specific types of insurers with an analysis of the property and liability insurers since the implications of statutory accounting tend to have more impact in this field. As a point of departure, we will discuss the unusual requirements of statutory accounting that result in a combination of a cash and accrual system of accounting.

![]()

Concept of Earned Premiums

Most businesses count sales as income when the sale is made and make no provision for the possible contingency of return sales. Insurance, on the other hand, is unusual in that it collects in advance for a product to be delivered in the future. Although premiums are paid in advance, the insurers' obligations under the contracts issued are all in the future. If the insurance company were permitted to use premiums currently being collected for future protection to meet obligations paid for in the past, it would be perpetrating a fraud on current purchasers. The only way the advance premium form of operation can be safely administered is to require insurance companies to make some provision in their financial statements recognizing that although premiums have been collected, the company has not fulfilled the obligations the premiums represent. This is done in two ways. First, insurers are permitted to include premiums as income only as the premiums become earned, that is, only as the time for which protection is provided passes. In addition, the insurer is required to establish a deferred income account as a liability, called the unearned premium reserve, the primary purpose of which is to place a claim against assets that will presumably be required to pay losses occurring in the future.

Unearned Premium Reserve The unearned premium reserve represents the premiums that insureds have paid in advance for the unexpired terms of their outstanding policies. Just as insureds carry prepaid insurance premiums as an asset on their books, so the insurance company enters them as a liability on its books. For each policy, the unearned premium reserve at the inception of the policy period is equal to the entire gross premium that insureds have paid. During the policy period, the unearned premium reserve for the policy declines steadily to zero by a mathematical formula. The unearned premium reserve is computed by tabulating the premiums on policies in force according to the year (or month) of issue and the term. It is customary to assume that policies issued during any period were uniformly distributed over that time. If the income over the period is uniformly distributed, the result is the same as if the policies had been written at the interval's midpoint. For example, annual policies written during the first month of the year will almost have expired by the end of the year, while those written at year's end will still have 11 months to run. Thus, at the end of a given year, annual policies written during the calendar year are assumed to have been in force, on average, for half of their term and still have half to run. To illustrate, if the insurance company writes $100,000 in premiums each month during the year, total premiums written that year will be $1.2 million. Assuming that all insurance sold consists of annual policies, the company will have earned $600,000 of the total written by the end of the year and will have an unearned premium reserve for these policies of $600,000.7

![]()

Incurred Losses

In calculating the losses sustained during a particular period, the statutory approach to accounting uses the matching concept, in that losses are compared with premiums earned. Because there may be delays between the occurrence of a loss and the time when it is paid, statutory accounting makes a distinction between incurred losses and paid losses. Incurred losses refer to those losses taking place during the particular period under consideration, regardless of when they are paid. Paid losses refer to losses paid during a particular period regardless of the time that the loss occurred. The difference between paid and incurred losses is recognized through liability accounts called loss or claim reserves.

Loss Reserves Loss reserves are of two major types: a reserve for losses reported but not paid and a reserve for losses that have occurred but have not been reported to the insurance company. Reserves for losses reported but not yet paid can be established by an examination of each claim and an approximation based on the predicted ultimate loss. Alternatively, averaging formulas can be applied to blocks of outstanding claims. The reserve for losses incurred but not reported (losses the insurer presumes have occurred but have not been submitted because of a lag in claim reporting) are usually estimated on the basis of the past experience of the insurer.

![]()

Expenses Incurred

For the purpose of statutory accounting, all commissions and other expenses in acquiring business are required to be charged against revenue when they are incurred. Experience has indicated that a large portion of a company's expenses (perhaps as much as 80 to 90 percent) originates with the cost of writing new or renewal policies. Even though these expenses are charged against revenue when incurred, the insurer is required to establish an unearned premium reserve equal to the entire premium on a policy. This means there is a redundancy in the unearned premium reserve; since expenses have been paid, the unearned premium reserve is higher than need be. This, in turn, means surplus is understated to the extent of the excess in the unearned premium reserve.8

![]()

Summary of Operations

There are two sources of profit or contribution to surplus for a property and liability insurer: underwriting gains and investments. The annual statement summarizes the results of operations in these areas.

Summary of Underwriting Results—Statutory Profit or Loss The combination of a cash basis of accounting for expenses and an accrual basis for premiums can, as one might suspect, create distortions in the reported underwriting results of an insurer. Since expenses must be paid when the policy is written and before the premium income has been totally earned and the premiums are included in the computation only as earned, the net effect is to understate profit whenever premiums written exceed premiums earned (when premium volume is increasing) and to overstate profit when premiums earned exceed premiums written (when premium volume is declining). This can be illustrated by an example:

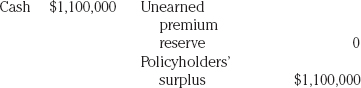

The XYZ Insurance Company, a newly organized stock company, is about to go into business. At the time of its organization, its balance sheet looks something like this:

We will assume the expected and actual loss ratio on the policies written is 50 percent and expenses incurred are 40 percent of premiums written, leaving a 10 percent profit.

During the first year of operation, the company writes $1 million in annualized premiums, distributed equally throughout the year. At the end of the year, half of these premiums will have been earned, and the unearned premium reserve will be $500,000. The income statement for the initial year of operation will indicate the following:

| Premiums earned | $500,000 |

| Expenses incurred (40% of premiums written) | −400,000 |

| Losses incurred (50% of premiums earned) | −250,000 |

| Statutory profit (loss) | ($150,000) |

Now, the company did not lose money during the year, but under the assumptions required in the statutory computation, a loss of $150,000 is indicated. This loss is an illusion created by premiums that are included in the computation only as they are earned; expenses are included as they are paid. The balance sheet shows that cash will have increased by $350,000 ($1 million in premiums minus $400,000 in expenses minus $250,000 in losses), while liabilities will have increased by the amount of unearned premiums. The amount by which the increase in liabilities exceeds the increase in assets represents a reduction in the amount of the company's surplus. The balance sheet at the end of the first year of operation would appear as follows:9

To illustrate the effect of a decline in premium volume, let us assume the insurer writes no new business in the second year and the unearned premiums at the beginning of the year all become earned. The summary of operations for the second year would appear as follows:

| Premiums earned | $500,000 |

| Expenses incurred (40% of premiums written) | 0 |

| Losses incurred (50% of premiums earned) | −250,000 |

| Statutory profit (loss) | $250,000 |

At the end of this second year in which no new policies were issued, liabilities will have been reduced by $500,000 (the amount of unearned premiums that became earned), and cash will have been reduced by the amount of the $250,000 in losses paid. The resulting balance sheet would appear as follows:

Several pertinent points can be recognized from the preceding simulation. First, it illustrates the manner in which statutory accounting distorts the results of an insurer's operations. During a year when premium volume is growing, the necessary increase in the unearned premium reserve will result in an understatement of the underwriting gain and may even cause the company to report a statutory loss. The requirements of statutory accounting and the redundancy in the unearned premium reserve allow a company's operations to appear more profitable than they are during periods of declining business in force and less profitable in periods when business in force is increasing.

A second significant point is that an increase in premium writings, other things being equal, will result in a reduction in policyholders' surplus. The insurer's management must constantly watch the growth of its business to make certain that a balance is maintained between its liabilities and its surplus to policyholders. Although no consensus exists on what the ratio should be, agreement is widespread that there is some minimum desirable ratio of policyholders' surplus to premiums written or to the unearned premium reserve.10 This means that the drain on surplus created by the statutory accounting requirements places a limit on the ability of an insurer to write new business.

Investment Results The investment income of a property and liability insurer is composed of interest on bonds, dividends on stocks, and interest on collateral loans and bank deposits. Investment income is shown separately from the results of underwriting.

Statutory investment income does not include unrealized capital gains or losses. These result from the statutory requirement that stocks be carried by insurance companies at market value. If the market value of stocks held by the company increases, the company has unrealized capital gains; if the value of stocks held decreases, it has unrealized losses. These unrealized gains and losses are not included in the insurer's statement of operations but are entered directly as increases or decreases in policyholders' surplus.

An Indicator of Underwriting Profitability—The Combined Ratio Statutory accounting procedures provide little in the way of an accurate picture regarding the true profitability of underwriting operations. A statutory loss may be the result of an increase in the amount of profitable business being written; or it could be the result of poor underwriting experience on a level or declining volume of business.

At this point, the reader may be wondering if insurance companies ever know whether they are making a profit. The obvious answer is yes. However, instead of depending on the statutory figures, informed observers gauge the profitability of a given company on the basis of its combined ratio, which is derived by adding the loss ratio and the expense ratio for the period under consideration. The loss ratio is computed by dividing losses incurred during the year by premiums earned. The expense ratio is computed by dividing expenses incurred by premiums written. Because the loss ratio is computed on the basis of losses incurred to premiums earned and the expense ratio is based on premiums written, the combined ratio merges data that are not precisely comparable. Nevertheless, the ratio is widely used as an indication of the trade profit of an insurer. If the total of these two ratios is less than 100 percent for the year, underwriting was conducted at a profit, and in the degree indicated.

![]()

LIFE INSURANCE COMPANIES

![]()

The statutory accounting procedures applicable to life insurers, like those required of property and liability insurers, differ from GAAP. In addition, principally because of the long-term nature of life insurance contracts, the statutory procedures used in life insurance also differ from those used in the property and liability field. Life insurance policies usually run for many years from the date of issue and entail a longer commitment on the part of the insurer that must be recognized in the accounting procedures.

![]()

Life Insurer Assets

One of the principal differences in the financial structure of life insurers and property and liability insurers is in the composition of assets. As in the property and liability segment, life insurers distinguish between admitted and nonadmitted assets. However, as we noted in the preceding chapter, the latter tend to concentrate their investments in bonds and mortgages, with only a small amount of total assets invested in stocks (excluding separate account assets). Because the mortgages and most bonds are carried at amortized value, the listed or book value of a life insurer's assets tends to be more immune from fluctuations than does that of a property and liability company.

![]()

Life Insurer Liabilities

The principal liabilities of a life insurer, like those of a property and liability insurer, are its obligations to its policyholders. The major liabilities appearing on the balance sheet of a life insurance company include policy reserves, reserves on supplementary contracts, dividends left to accumulate, reserves for unpaid claims, and asset valuation reserve and interest maintenance reserve.

Policy Reserves Unearned premium reserves arise in life insurance, but here they are called policy reserves. Under most forms of life insurance, the insured pays more than the cost of protection during the early years of the contract, and the insurer is required to set up policy reserves representing the amount of this overpayment. In addition, many forms of life insurance and annuities have a substantial savings or investment element, under which the insured accumulates cash values that will be paid out at some maturity date in the future. Policy reserves must be established for these contracts.

Like the reserves in the property and liability field, life insurance policy reserves contain an element of redundancy. In life insurance, the redundancy arises from the rates and reserves being computed using interest assumptions that are lower than actual interest earnings, and mortality assumptions that are higher than actual experience.

Specific requirements for the calculation of minimum life insurance policy reserves are established by the NAIC's Standard Valuation Law, which has been enacted by the various states. The law mandates the specific mortality table and interest rate assumptions that must be used as well as the formula for calculating the reserve. This rules-based system of regulating life insurer reserves has been criticized in recent years. Since 1980, life insurance products have become increasingly complicated. Insurers have more underwriting classes, and many policies contain minimum guarantees that were not contemplated when the Standard Valuation Law was developed. Critics argue that, in some cases, reserves are excessively conservative, while in other cases, the failure to recognize new risks can result in inadequate reserves. In response, the NAIC is developing a new system of principles-based reserving (PBR), which will rely more on actuarial judgment in setting reserves. PBR was adopted by the NAIC in November 2012. It will not become effective, however, until it has been enacted in at least 42 states representing at least 75 percent of U.S. life insurance premiums.

Reserves on Supplementary Contracts Not all death claims or endowment maturities are paid out in a lump sum. In many instances, the beneficiary may elect to leave the policy proceeds with the insurance company and draw only the interest, or interest and a part of the principal. These arrangements are evidenced by supplementary contracts, for which the insurer must establish a reserve recognizing its obligation to the beneficiary.

Dividends Left to Accumulate Life insurance policies frequently pay dividends, which represent the insured's participation in the divisible surplus of the company. Companies permit the insured several options in connection with these dividends, one of which is to leave them on deposit with the company, where they accumulate interest. When the insured elects to leave the dividends on deposit, the insurer establishes a reserve, recognizing its liability to the insured.

Reserves for Unpaid Claims As in the case of property and liability insurers, life insurance companies establish reserves for unpaid claims. These include reserves for claims that have been reported to the company and are in the process of settlement, and a reserve for possible deaths that, because of a delay in reporting, may not be known to the company. Since life insurance claims tend to be settled quickly, the amount of these reserves is generally small.

Asset Valuation Reserve and Interest Maintenance Reserve Since 1951, life insurers have been required to include special liabilities in their annual statement to provide a cushion against adverse fluctuations in the value of assets held. The original requirement was for a Mandatory Security Valuation Reserve, which addressed stock and bond values. This was replaced in 1992 by two reserves: The Asset Valuation Reserve and the Interest Maintenance Reserve. The new reserves address all invested assets, not just stocks and bonds.11

![]()

Life Insurers' Policyholders' Surplus

Because life insurance operations are relatively stable, they do not require surplus in the same amounts as those of property and liability insurers. The policyholders' surplus of life insurers tends to represent a much smaller percentage of total assets than does that of property and liability insurers. Although the policyholders' surplus of property and liability insurers generally equals somewhere between 35 and 50 percent of total assets, policy holders' surplus of life insurers averages less than 10 percent of total assets. Some states (e.g., New York) impose legal limits on the level of surplus.

![]()

Life Insurer Summary of Operations

The annual summary of a life insurer's operations, as contained in the NAIC Annual Statement, includes three principal items of income and three major deductions from income:

| Life Insurer Income | Deductions from Income |

| Premiums from policyholders | Contractual benefits to policyholders and beneficiaries |

| Considerations on supplementary contracts and dividends left with the company to accumulate | Increases in required reserves on policies in force |

| Investment income | Operating expenses and taxes |

Income Although life insurers do not use the concept of earned premiums as do property and liability insurers, they accomplish the same end in a different manner. All premiums due or received are included as income during the year in which they are collected or become due, regardless of whether they represent payment for current or future protection. Then, to recognize the company's obligations in connection with premiums paid for future protection, the net increase in the legal reserves is deducted from income. The effect is to include as net income only those premiums received for present protection.

Similarly, when an insured dies or an endowment policy matures, the claim is treated as a deduction from income, regardless of whether the policy proceeds are paid. When the policy proceeds are left with the company under a supplementary contract, the amount of the benefit is treated as the premium on the supplementary contract and is included as income. Dividends left with the company to accumulate at interest are handled in the same fashion. When a dividend becomes payable to an insured, it is treated as a deduction from income even though the insured may elect to leave the dividend on deposit. Dividends left on deposit, after having been deducted from income as a contractual benefit paid to policyholders, are included as income under dividends left on deposit. The investment income of a life insurer is composed of interest on bonds; mortgage loans, collateral loans, and bank deposits; dividends on stocks; and real estate income. Investment income is reported on a gross basis and on a net basis after deduction of investment expenses and depreciation of investment real estate property. Investments generate a significant part of the income of life insurers. In 2005, net investment income was about 25 percent of total revenues for all companies in this industry sector.

Deductions from Income The largest deduction from income consists of benefits paid to policyholders, including death benefits, disability benefits, dividends, and cash surrender values. Such benefits amounted to about 59 percent of income in 2011.

The second largest deduction is the deduction for required reserves, which amounts to about 17 percent of income. Transfers to separate accounts are another four percent of income. The deduction of the increase in required reserves on policies in force compensates for the inclusion of all premium income from policyholders in the income section of the statement.

Life insurance company operating expenses, based on industry aggregates, totaled about 14 percent of income during 2011. Included in the 2011 total were about 7 percent of income for general and administrative expenses and about 6 percent for commissions to agents.

![]()

Surplus Drain in Life Insurance

The surplus of a life insurance company is subject to a drain during periods of increasing sales similar to the drain a property and liability insurer experiences. As an incentive to their agents to produce new business continually, life insurance companies pay very high first-year commissions, sometimes more than 100 percent of the first-year premium. In a sense, it might be appropriate to view this first-year commission as an investment in the production of future premiums under the policy. However, under the statutory provisions governing life insurance accounting, all expenses of operation must be charged against income when they are incurred. This means that the sale of a new policy generally results in a reduction in surplus since the commissions and other expenses together with the required contribution to legal reserves exceed the premium received. Unlike the problem in the property and liability field, state statutes have recognized this problem and permit life insurers to compensate for high first-year policy expenses through a modified reserving system. Under these modified reserving systems, the insurer is permitted to compensate for the initial expenses associated with the policy by deferring the establishment of the first-year reserve, thereby freeing the bulk of the initial premium for the payment of expenses.12

![]()

REINSURANCE

![]()

Nature of Reinsurance

Reinsurance is a device whereby an insurance company may avoid catastrophic losses in the operation of the insurance mechanism. As the term indicates, reinsurance is insurance for insurers. It is based on the same principles of sharing and transfer as insurance itself. To protect themselves against the catastrophe of a comparatively large single loss or a large number of small losses caused by a single occurrence, insurance companies devised the concept of reinsurance. In a reinsurance transaction, the insurer seeking reinsurance is known as the direct writer or the ceding company, while the company assuming part of the risk is known as the reinsurer. That portion of a risk that the direct writer retains is called the net line or the net retention. The act of transferring a part of the risk to the reinsurance company is called ceding, and that portion of the risk passed on to the reinsurer is called the cession. Reinsurance had a simple beginning. When the insurer encountered a risk that was too large to handle safely, the insurer shopped around for another insurance company willing to take a portion of the risk in return for a portion of the premium. A few current reinsurance operations are still conducted in this manner, which is called facultative or street reinsurance. In street reinsurance, each risk represents a separate case for the insurer, and the terms of reinsurance must be negotiated when the direct writer finds another insurer that will accept a portion of the risk. The ever-present danger is that a devastating loss might occur before the reinsurance becomes effective. The cumbersome nature of the facultative system led to the development of modern reinsurance treaties.

![]()

Types of Reinsurance Treaties

Two types of reinsurance treaties are available: facultative and automatic. Under a facultative treaty, the risks are considered individually by both parties. Each risk is submitted by the direct writer to the reinsurer for acceptance or rejection, and the direct writer is not even bound to submit the risks in the first place. However, the terms under which reinsurance will take place are spelled out, and once the risk has been submitted and accepted, the advance arrangements apply; until then, the direct writer carries the entire risk.

Under an automatic treaty, the reinsurer agrees in advance to accept a portion of the gross line of the direct writing company or a portion of certain risks that meet the reinsurance underwriting rules of the reinsurer. The direct writer is obligated to cede a portion of the risk to which the automatic treaty applies.

![]()

Reinsurance in Property and Liability Insurance

Risk is shared under reinsurance agreements in the field of property and liability insurance in two broad ways. The reinsurance agreement may require the reinsurer to share in every loss that occurs to a reinsured risk, or it may require the reinsurer to pay only after a loss reaches a certain size. The first arrangement is called proportional reinsurance and includes quota share treaties and surplus line treaties. The second approach is called excess-loss reinsurance.

Quota Share Treaty Under a quota share treaty, the direct-writing company and the reinsurance company agree to share the amount of each risk on some percentage basis. Thus, the ABC Mutual Insurance Company (the direct writer) may have a 50 percent quota share treaty with the DEF Reinsurance Company (reinsurer). Under such an agreement, the DEF Reinsurance Company will pay 50 percent of any losses arising from those risks subject to the reinsurance treaty. In return, the ABC Mutual Insurance Company will pay the DEF Reinsurance Company 50 percent of the premiums it receives from the insureds (with a reasonable allowance made to ABC for the agent's commission and other expenses connected with putting the business on the books).

Surplus Treaty Under a surplus line treaty, the reinsurer agrees to accept some amount of insurance on each risk in excess of a specified net retention. Normally, the amount the reinsurer is obligated to accept is referred to as a number of “lines” and is expressed as some multiple of the retention. A given treaty might specify a net retention of $10,000 with five lines. Under such a treaty, if the direct writer writes a $10,000 policy, no reinsurance is involved, but the reinsurer will accept the excess of policies over $10,000 up to $50,000. These treaties may be first-surplus treaties, second-surplus, and so on. A second-surplus treaty fits over a first-surplus treaty, assuming any excess of the first treaty, and so on for a third or fourth treaty. To illustrate, let us assume the ABC Mutual Insurance Company (the direct writer), has a first-surplus treaty with a $10,000 net retention and five lines with the DEF Reinsurance Company and a second-surplus treaty with five lines with the GHI Reinsurance Company. If ABC sells a $100,000 policy, it must, under the terms of both agreements, retain $10,000. The DEF Reinsurance Company will then assume $50,000 and GHI will assume $40,000:

| ABC Mutual Insurance Company | $10,000 |

| DEF Reinsurance Company | 50,000 |

| GHI Reinsurance Company | 40,000 |

Any loss under this policy would be shared on the basis of the amount of total insurance each company carries. Thus, ABC would pay 10 percent of any loss, DEF would pay 50 percent, and GHI would pay 40 percent. The premium would be divided in the same proportion, again with a reasonable allowance from the reinsurers to the direct writer for the expense of putting the policy on the books.

Excess-of-Loss Treaty Under an excess-of-loss treaty, the reinsurer is bound to pay only when a loss exceeds a certain amount. In essence, an excessloss treaty is an insurance policy that has a large deductible taken out by the direct writer. The excess loss treaty may be written to cover a specific risk or to cover many risks suffering loss from a single occurrence. Such a treaty might, for example, require the reinsurer to pay after the direct-writing company had sustained a loss of $10,000 on a specific piece of property, or it might require payment by the reinsurer if the direct writer suffered loss in excess of $50,000 from any one occurrence. There is, of course, a designated maximum limit of liability for the reinsurer.

Pooling Still another method of reinsurance is pooling. The pooling arrangement may be similar to that used in aviation insurance, under the terms of which each member assumes a percentage of every risk written by a member of the pool. This pooling arrangement is similar to a quota share treaty. On the other hand, the pool may provide a maximum loss limit to any one insurer from a single loss. After a member of the pool has suffered a loss in excess of a specified amount (e.g., $100,000 as a result of one disaster), the other members of the pool share the remainder of the loss.

![]()

Reinsurance in Life Insurance

In the field of life insurance, reinsurance may take one of two forms: the term insurance approach and the coinsurance approach. Under the term insurance approach, the direct writer purchases yearly renewable term insurance equal to the difference between the face value of the policy and the reserve, which is the amount at risk for the company. The coinsurance approach to reinsurance in life insurance is quite similar to the quota share approach in property and liability. Under this approach, the ceding company transfers some portion of the face amount of the policy to the reinsurer, and the reinsurer becomes liable for its proportional share of the death claim. In addition, the reinsurer becomes responsible for the maintenance of the policy reserve on its share of the policy.

![]()

Functions of Reinsurance

Reinsurance serves two important purposes. The first is the spreading of risk. Insurance companies are able to avoid catastrophic losses by passing on a portion of any risk too large to handle. In addition, through excess-loss reinsurance arrangements, a company may protect itself against a single occurrence of catastrophic scope. Smaller companies are able to insure exposures they could not otherwise handle within the bounds of safety.

The second function reinsurance performs is not as immediately obvious: It is a financial function. As we have seen, when the premium volume of an insurance company is expanding, the net result will be a drain on the company's surplus. With an expanding premium volume, a company faces a dilemma. The business it is writing may be profitable, but because of the requirements of the unearned premium reserve, its surplus may be declining and may reach a dangerously low level. We say “dangerously low” because, although there is no standard, the amount of new business a company may write is a function of its policyholders' surplus. In the absence of some other alternative, a company could expand only to a certain point and would then be required to stop and wait for the premiums to become earned, freeing surplus.

Reinsurance provides a solution to this dilemma. When the direct-writing company reinsures a portion of the business it has written under a quota share or surplus line treaty, it pays a proportional share of the premium collected to the reinsurer. The reinsurer then establishes the unearned premium reserves or policy reserves required, and the direct writer is relieved of the obligation to maintain such reserves. Since the direct writer has incurred expenses in acquiring the business, the reinsurer pays the direct-writing company a commission for having put the business on the books. The payment of the ceding commission by the reinsurer to the direct writer means that the unearned premium reserve is reduced by more than the cash that is reduced, resulting in an increase in surplus. Thus, if the direct writer transfers $100,000 in premiums to the reinsurer, the unearned premium reserve of the direct writer is reduced by $100,000. The payment to the reinsurer is $100,000 minus a ceding commission of 40 percent, or $60,000. Since assets have been reduced by $60,000 and liabilities have been reduced by $100,000, surplus is increased by $40,000. When reinsurance is used on a continuing basis, the net drain on the surplus of the direct-writing company is reduced. In addition, the market is greatly increased since excess capacity of one insurer may be transferred to another through reinsurance.

![]()

Risk-Financing Alternatives to Reinsurance

Our discussion of insurance company financial operations would be incomplete without mentioning of one of the most recent developments in insurance finance. This is the securitization of insurable risk, through which insurance risk is transferred to the financial markets via insurance-linked securities or ILS.

Like reinsurance, securitization is designed to transfer a part of an insurer's underwriting risk to another party. To date, the vast majority of securitizations have dealt with the transfer of catastrophic risk, such as hurricanes and earthquakes although other risks are starting to be transferred. Securitization differs from reinsurance as an approach to risk financing by its direct link to the capital markets. Instead of transferring specific portfolios of risks to a reinsurer, insurers make what, in a sense, is a side bet with another party (e.g., an investor or speculator) on whether a catastrophe loss will occur. These side bets take the form of securities traded in a market or, in some cases, private placements. Investors in ILS become a source of external funding for the industry that can serve as a backstop to protect surplus against catastrophe losses. The property and liability industry has about $550 billion in surplus, which pales in comparison with the trillions invested in securities markets. If insurance risks can be commoditized into tradable securities, the proponents of securitization argue that an enormous source of funds outside the industry can be tapped.

The question arises as to why parties outside the property and liability insurance industry would be interested in investing in such securities. The advocates of insurance securitization suggest several features could appeal to the external market.

First, ILS offer the potential for diversification; they fluctuate with a different pattern of gains and losses than stocks and bonds. Hurricane losses, for example, vary with the weather, not with general economic conditions. Because of this, the returns on ILS are believed to be generally uncorrelated with the financial markets. This, coupled with a relatively high return (in years in which catastrophe losses are low) could make these securities attractive to institutional investors outside the insurance industry. In addition, there are times when investors believe that the stock market is overvalued and become nervous over the prospect of a serious decline. Here, again, the largely uncorrelated nature of ILS is an appealing feature.

The most common mechanism for insurance securitization today is catastrophe bonds (also called act of God bonds and cat bonds). Risk may also be transferred through insurance derivatives such as futures and options. Derivatives are financial instruments whose value is derived (hence the name) from the value of commodity prices, interest rates, stock market prices, foreign exchange rates, and now insurance indexes.

Catastrophe Bonds Cat bonds are bonds in which the repayment terms vary depending on the occurrence of a specific catastrophe. If no catastrophe loss occurs, the investor obtains a stream of payments that return interest and principal. However, if a covered catastrophe occurs, the issuer does not have to repay some or all of the interest, principal, or both. In this way, the bond issuer obtains funds from the bond investors to cover its catastrophe losses. Investors who purchase cat bonds are speculating that, during a particular period, a catastrophic loss will not affect the regions covered by the bonds. If good weather prevails during the bond period, the investor wins. If a disaster strikes, the investor loses. It is the willingness of the speculator to make a side bet with the insurer that is the essential requirement for cat bonds. Most cat bonds have been issued by insurance companies or reinsurers, but they have also been used by some governments and corporations.13

The bond's trigger, which determines when the issuer recovers under the bond, is a particularly important feature of the bond. The trigger may be a function of the actual losses of the firm issuing the bond, some industry-wide index of losses, the results of a specific model's estimate of the loss, or a parametric trigger that is a function of the measured intensity of the event (e.g., the magnitude of an earthquake). Because investors tend to prefer a trigger the insurer cannot manipulate, many triggers are a function of an industry-wide loss index or the outcome of a specific catastrophe model. Thus, the insurer's recovery under the bond may differ from its actual losses, a problem known as basis risk.14

Cat bond activity has tended to increase following catastrophic losses to the insurance industry, increasing the industry's need for capital. The first catastrophe bonds were issued following Hurricane Andrew and the Northridge earthquake in the 1990s. Securitization activity increased following the hurricanes of 2004 and 2005 but dropped during the financial crisis. It has recovered in recent years, and there were an estimated $16.5 billion in cat bonds outstanding by year-end 2012. While this pales in comparison to total insurance industry surplus, cat bonds are becoming an increasingly important mechanism for insurers and reinsurers to manage their property catastrophe exposures.15

Securitizations in Life Insurance As with weather-related catastrophes, there have been transactions that attempts to transfer catastrophic mortality risk to the capital markets. Early bonds covered extreme mortality risk. More recently, some life insurers have transferred longevity risk to the capital markets.16 Most securitization activity by U.S. life insurers, however, has had a different motivation. In the United States, life insurance reserve requirements established by the NAIC tend to be conservative, and most U.S. life insurance securitizations have had the primary goal of releasing the excess reserves from an insurer's balance sheets.17 European life insurance companies have also engaged in securitization transactions aimed at providing immediate recognition of future profits on an existing book of business. In effect, the insurers are selling the future premium payments on the business.

Catastrophe Futures and Options A futures contract is a binding contract providing for the delivery of a specified quantity of some commodity or financial instrument at some future specified date. Futures originated as a means whereby the producers of agricultural products could hedge against a decline in the prices for their output or by which a manufacturer could hedge against an increase in the price of raw materials. In the 1970s, a market developed in financial futures, and it was probably only a matter of time before insurance futures were devised. In December 1992, the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) began trading two versions of catastrophe insurance futures. The initial response was sluggish, and in 1995, the CBOT shifted to a new line of catastrophe insurance options known as PCS options (because they are based on a benchmark of catastrophe loss estimates, provided by the firm Property Claim Services). The volume of trades in PCS options proved to be disappointing and the CBOT discontinued these options at the end of 2000.18

The value of a catastrophe insurance option is directly linked to the industry's losses from natural disasters in a particular area over a specified time period. The greater the losses, the higher the value of the cash settlement if the option is exercised. By acquiring call options, which are the right to buy futures contracts whose price is pegged to disaster losses, an insurer could earn a trading profit and arrange a source of funds to pay claims for catastrophe losses. By taking the other side of the trade, investors could collect a favorable return during periods of favorable loss experience.

If this sounds like a win-lose situation, it is because it is. Hedging operations are made possible by speculators who buy and sell futures options in the hope of making a profit as a result of a change in price. For the speculator, the futures option is a speculative risk. Like stock index futures, insurance futures options will be a zero-sum game. For every winner, there will be a loser. When an insurer buys an insurance futures option in anticipation of increasing losses, the other half of the contract is filled by someone who is betting against the occurrence of a catastrophe.

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) began trading hurricane futures and options on the futures in March 2007. In mid-2013, three categories of hurricane futures and options contracts were offered, with the value of each contract based on the CME Hurricane Index (CHI), a proprietary index that predicts the potential damage from a storm based on its maximum wind velocity and size. The Futures and Options Contracts reflect the value of the CHI for a single named storm, the Seasonal Futures and Options Contracts reflect the accumulated CHI from all hurricanes over a calendar year, and the Seasonal Maximum Futures and Options Contracts reflect damage from the largest hurricane to make landfall during a calendar year. The volume of trading has been limited.

Sidecars Sidecars do not represent a form of securitization, but they are an increasingly important mechanism to facilitate the entry of third-party capital into the reinsurance market. A sidecar is a separate vehicle established for third party investors to take a portion of the risk underwritten by a reinsurer. Sidecars first became popular after Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Losses from the hurricane forced reinsurers to replenish their capital, and several reinsurers found sidecars an attractive mechanism for doing so. In a sidecar arrangement, the sidecar is capitalized by investors, and the sponsoring reinsurer cedes a portion of its business to the sidecar, typically in a quota share arrangement. The sidecar investors bear the risk and the return of the ceded business. The sponsoring reinsurer is responsible for underwriting and other management functions. For investors, a sidecar enables them to take a specific set of risks (e.g., property risks), and limit their exposure to the reinsurer's other business. For the sponsoring reinsurer, the sidecar provides a source of additional capital that enables it to write more business. In most cases, sidecars are intended to be a temporary source of capital. They are structured to terminate after a few years, allowing the investors to withdraw their capital.19

Other Insurance-linked Securities There are other techniques for transfering insurance risk to the capital markets, including catastrophe swaps, industry loss warranties (ILWs), and contingent capital. An ILW is like a reinsurance contract but with the payment based on some industry loss index, rather than the insurer's losses. Unlike cat bonds, these are private transactions, often between an insurer or reinsurer and a hedge fund.20

Contingent capital gives the insurer the right to sell securities (e.g., shares of its stock) at a predetermined price if a catastrophe occurs within a given time frame. This addresses the insurer's concern that it might suffer losses and be forced to replenish capital when its stock price is low.21

Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF) Following the 2004 hurricanes, which damaged several Caribbean countries, the members of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) requested assistance from the World Bank in creating a Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF). The facility became operational in June 2007. Eighteen Caribbean countries participated, and initial capital was provided by $47.5 million in pledges from Canada, France, the United Kingdom (UK), the Caribbean Development Bank, and the World Bank. The CCRIF operates much like an insurance arrangement, providing participating countries with immediate access to funds in the event of a hurricane or earthquake. However, in the event of a loss, the insurance payment is based on a parametric trigger. That is, it varies with the intensity of the event rather than the actual damage incurred.

The CCRIF is controlled by the participating governments and contributing donors. Member countries determine the amount of coverage they wish to purchase and pay a premium based on their exposure. In addition to its own capital, the CCRIF uses reinsurance and capital markets instruments to increase its capacity.22

While it is too early to judge the success of this facility, supporters hope it will serve as a pilot program that could be replicated in other geographic areas.

![]()

TAXATION OF INSURANCE COMPANIES

![]()

Insurance companies, like all business corporations, are subject to federal, state, and local taxes. At the federal level, insurers are subject to the federal income tax. At the state level, they pay income and property taxes like other businesses and, in addition, are liable for a number of special taxes levied on insurers, the most important of which is the premium tax.

![]()

State Premium Tax

Taxation of insurance companies by the states grew out of the states' need for revenue and a desire to protect domestic insurers by a tariff on out-of-state companies. The premium tax spread from state to state as a retaliatory measure against taxes imposed by each state on outside insurance. As time went by, most states came to levy the premium tax on the premium income of domestic and foreign insurers.23

Every state currently imposes a premium tax on insurers operating within its borders. In essence, this tax is a sales tax on the premiums for all policies sold by an insurer within the state. The amount of the tax varies among the states; the maximum in any state is 4 percent, with the most typical amount being 2 percent. The tax paid by the insurer is added to the cost of the insurance contract and is passed on to the policyholder. At one time, over half of the states imposed higher taxes on out-of-state insurers, but discriminatory taxation has largely disappeared today.24

In addition to the premium tax, the states charge companies and agents license fees before they can solicit business in the state. The total revenue received by the insurance department of the states exceeds the costs of operating these departments; this makes the insurance department in every state an income-producing agency. In fact, a critical concern of the states in the state-versus-federal-regulation debate is one of revenue. It has been said that “the power to regulate is the power to tax,” and many state officials fear that should the federal government assume responsibility for the regulation of insurance, Congress would begin to look with growing interest at the state insurance tax revenues, which amount to more than $1 billion annually.

![]()

Federal Income Taxes

For the purpose of taxation under the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), insurance companies are classified into three categories: life insurance companies, non-life mutual insurance companies, and insurance companies other than life or mutual. In general, all three classes are subject to the same tax rates as are other corporations. However, they differ from other corporations, and from each other, in the manner in which taxable income is determined.25

Life Insurance Companies Life insurance companies are taxed at standard corporate rates on their life insurance company taxable income (LICTI), which is life insurance gross income minus deductions. Life insurance gross income includes premiums, decreases in reserves, and other standard elements of gross income, such as investment income. Deductions include expenses incurred, death benefits, increases in certain reserves, policyholder dividends, and certain miscellaneous deductions.

Among the special deductions, the IRC permits a small-company deduction to life insurers with less than $500 million in assets. The small-company deduction allows an eligible insurer to deduct 60 percent of its first $3 million in tentative LICTI, and the deduction is phased out as tentative LICTI reaches $15 million. If the phase-out of the deduction applies, the deduction is reduced by 15 percent of the excess of tentative LICTI over $3 million and is phased out when LICTI reaches $15 million.

Although life insurers are permitted to deduct increases in their reserves, the 1984 tax act dictates the method that must be used. Reserves for tax purposes cannot exceed the amount taken into account in computing statutory (annual statement) reserves.

The most recent change in the taxation of life insurers was enacted as a part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990 (OBRA). Under the provisions introduced by OBRA, life insurers are required to capitalize and amortize policy acquisition expense. As you will recall from our discussion of life insurer finances, the high first-year commissions on life insurance policies produce an underwriting loss, which is recouped as future premiums are earned. The IRC requires this deferral of the deduction, thereby increasing LICTI.26

Property and Liability Companies Property and liability insurers pay the usual corporate income tax on net underwriting profit and investment income. The manner in which taxable income is determined, however, reflects the unique conventions of statutory accounting. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA-86) substantially revised the provisions of the IRC under which property and liability insurance companies (and Blue Cross and Blue Shield organizations) are taxed.27 TRA-86 eliminated certain provisions related to the taxation of mutual insurers and introduced new rules to reflect the anomalies of statutory accounting.28

The first feature of statutory accounting addressed by TRA-86 was the treatment of the unearned premium reserve that results in a mismatching of revenues and expenses. Under the provisions of TRA-86, only 80 percent of the increase in the unearned premium reserve in a given year is deductible in computing taxes.

TRA-86 requires that property and liability loss reserves be discounted to reflect the time value of money. The annual deduction for incurred losses includes the increase in loss reserves, but the amount deducted is subject to statutory discounting. Any decrease in loss reserves results in income inclusion, also on a discounted basis. The discount rate used is based on the federal midterm rate.

Finally, the IRC disallows a portion (15 percent) of property and liability insurer's tax-exempt interest and dividends. This is accomplished by reducing the deduction for incurred losses by 15 percent of tax-exempt interest and deductible dividends.29

IMPORTANT TERMS AND CONCEPTS

annual statement

statutory accounting

GAAP

admitted assets

nonadmitted assets

policyholders' surplus

earned premiums

unearned premium reserve

reinsurance reserve

incurred losses

paid losses

loss reserves

statutory profit (loss)

loss ratio

expense ratio

combined ratio

written premiums

amortized value

policy reserves

supplementary contracts

reinsurance

ceding company

cession

facultative treaty

automatic treaty

proportional reinsurance

quota share reinsurance

surplus line reinsurance

excess-loss reinsurance

premium tax

insurance-linked securities

catastrophe bonds

asset valuation reserve

interest maintenance reserve

surplus drain

net retention

retrocession

life insurance company taxable income (LICTI)

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. What characteristics of the insurance business make reserves necessary?

2. Is the life insurance policy reserve more analogous to an unearned premium reserve or a loss reserve in the property and liability field?

3. Define the unearned premium reserve and briefly explain how it is calculated. Why is the unearned premium reserve often referred to as the “reinsurance reserve”?

4. What does it mean to say that a reserve is redundant? What type of reserves are considered to be redundant? Why?

5. The XYZ Insurance Company had an unearned premium reserve of $20 million at the end of 2006. During 2007, it wrote $25 million in annual premiums. At the end of 2007, its unearned premium reserve was $23 million. What were the earned premiums during 2007?

6. The XYZ Insurance Company had loss reserves of $7 million at the end of 2006. During 2007, it paid $7 million in losses, and had loss reserves in the amount of $6 million at the end of 2007. What were the incurred losses for 2007?

7. The financial statements of the XYZ Property and Liability Insurance Company indicate the following:

| Premiums written 2007 | $10,000,000 |

| Unearned premium reserve, Dec. 2006 | 9,000,000 |

| Unearned premium reserve, Dec. 2007 | 11,000,000 |

| Losses paid in 2007 | 6,000,000 |

| Loss reserves, Dec. 2006 | 5,000,000 |

| Loss reserves, Dec. 2007 | 4,000,000 |

| Underwriting expense incurred | 4,000,000 |

Compute the statutory profit or loss for the XYZ Company during 2007.

8. Give two specific reasons for reinsurance. Distinguish between facultative and treaty reinsurance.

9. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA-86) introduced several new elements into the taxation of property and liability insurers. In what way did the TRA-86 deal with the mismatching of revenues and expenses of property and liability insurers? How did TRA-86 deal with the redundancy in loss reserves?

10. Explain two techniques that may be used to estimate the true underwriting profit or loss of a property and liability insurance company.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. The primary emphasis in statutory accounting is supposedly on financial conservatism. However, some statutory techniques violate this principle. Discuss three ways in which statutory accounting is ultraconservative and two areas where the principle of conservatism is violated.

2. The NAIC has staunchly defended its need to have an accounting system for insurance companies that differs from GAAP. On what basis have they argued for a different system? Do you agree or disagree that a separate system is needed?

3. A noted insurance authority stated, “The insured should prefer to purchase insurance from a company that has a high loss ratio since this is evidence that the company is returning a high percentage of the premium dollars collected to its customers.” Explain why you agree or disagree with this position.

4. To what extent does the movement of surplus of a property and liability insurer indicate the profitability of the company's operations? Would the same be true for a life insurer?

5. “In view of the relationship of surplus to premiums that may be written, a severe decline in the stock market is likely to serve as a brake on price-cutting practices.” Explain the rationale behind this observation.

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Black, Kenneth Black, Jr., Harold D. Skipper, and Kenneth Black III Life and Health Insurance, 14th ed., Lucretian, LLC, 2013.

Government Accountability Office. Natural Catastrophe Insurance Coverage Remains a Challenge for State Programs (GAO-10-568R), 2010.

Government Accountability Office. Catastrophe Risk: U.S. and European Approaches to Insure Natural Catastrophe and Terrorism Risks (GAO-05-199), 2005.

Guy Carpenter Catastrophe Bond Update: First Quarter 2013. Available http://www.guycarp.com/portal/extranet/insights/briefingsPDF/2013/Catastrophe%20Bond%20Update%20First%20Quarter%202013.pdf?vid=5

Insurance Company Operations. Atlanta, Ga.: LOMA, 2012.

Insurance Accounting and Systems Association. Property-Casualty Insurance Accounting, 8th ed. Durham, N.C.: IASA, 2003.

Myhr, A. E. Insurance Operations, Regulation, and Statutory Accounting, 3rd ed. American Institute for Chartered Property Casualty Underwriters, 2011.

Powers, Harvey. “Insurance Securitization: A Ripe Market.” CPCU eJournal, Nov. 2012.

Swiss Re. Securitization—New Opportunities for Insurer and Investors, Sigma No. 7/2006. Zurich, Switzerland: Swiss Reinsurance Company, 2006.

Troxel, T. E. and G. F. Bouchie, Property-Liability Insurance Accounting and Finance, 4th ed. Malvern, Pa.: American Institute for Chartered Property Casualty Underwriters, 1995.

von Dahlen, Sebastian and Goetz von Peter. “Natural Catastrophes and Global Reinsurance: Exploring the Linkages.” BIS Quarterly, Dec. 2012.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| American Academy of Actuaries | www.actuary.org |

| Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility | www.ccrif.org |

| Insurance Accounting and Systems Association | www.iasa.org |

| Insurance Information Institute | www.iii.org |

| Reinsurance Association of America | www.reinsurance.org |

![]()

1In addition to the distinction between admitted assets and nonadmitted assets, insurance accounting distinguishes between ledger assets and nonledger assets. Ledger assets are assets at cost as carried in the general ledger of the company. They are identical with the assets carried by any business firm. Nonledger assets include those not normally reflected in the balance sheet, such as the excess of market value over the cost of stocks owned. Admitted assets = Ledger assets + Nonledger assets − Nonadmitted assets.

2FASB No. 115 applies to all commercial enterprises. Given the large amount of debt and equity securities held by insurers and other financial institutions, it is likely to have a significant impact on those companies.

3Bonds are evidences of debt and promise to pay their face value at maturity. At maturity, the bond of a solvent corporation will be worth its face value, but the market value of bonds may vary from this face value over time, depending on the bond's interest rate compared with the market rate. For example, assume that a 20 year $1000 bond was issued 10 years ago with a 5 percent interest rate. Now assume that the market rate on bonds with similar risk increases to 10 percent. The bond in question will decrease in value, since a $500 investment will generate the same return as the $1000 bond. Conversely, if the interest rate falls, the market value of the bond will increase above its face value. If a bond is purchased in the market for other than its face amount, the book value will differ from the bond and must gradually be adjusted over time so that it will equal the face of the bond at maturity. The process of gradually writing the value of the bond up or down so that the book value will equal the face at maturity is called amortizing.

4In 2009, at the height of the recent financial crisis, the NAIC adopted Statement of Statutory Accounting Principles (SSAP) 43R, which applies to loan-backed and structured securities, such as residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) and commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS). SSAP No. 43R may require insurers to recognize a loss on loan-backed securities even if they have the intent and ability to hold such securities to maturity. If the current market value of the security (i.e., its fair value) is less than its amortized cost, the insurer must determine whether the decline in value (or “impairment”) is “other than temporary.” The insurer must recognize any other than temporary impairment (OTTI) as a realized loss.

5The modern trend in accounting terminology is away from the term surplus. The term earned surplus is gradually changing to retained earnings, and paid-in surplus is being replaced by the term capital paid-in in excess of par. Nevertheless, because of the statutory reporting requirements and the connotation that the policyholders' surplus is the total excess of assets over liabilities, the term surplus is, and will probably remain, acceptable in insurance terminology.

6The use of the term reserve to indicate a liability will undoubtedly make your accounting professor turn purple. This usage is probably misleading to the layperson and is contradictory to modern accounting terminology. In general connotation, a reserve is a fund or asset accumulation. In addition, the term may refer to an asset valuation reserve, such as the reserve for depreciation although this term is declining in favor of accumulated depreciation. Finally, reserve may refer to earmarked retained earnings. Unless otherwise specified, when used in insurance accounting, the term reserve always refers to a liability.

7The most acceptable and most widely used method of calculating unearned premiums is called the monthly pro rata basis. Under this approach, 1/24 of the premium for an annual policy is considered earned during the month in which the policy is written, 1/12 is earned each month from month 2 through month 12, and 1/24 is earned in month 13.

8Those familiar with the property and liability insurance industry are aware of the inaccuracy in the figures presented in the insurer's balance sheets and make allowance for it. There is no universally accepted formula for doing this, but one method is to adjust surplus and the unearned premium reserve by the amount of the redundancy of the unearned premium reserve, usually considered to be about 35 percent.

9For the sake of simplicity, assume all losses are paid when incurred. In actual practice, the statement would include loss reserves.

10A rule of thumb that developed in the monoline era held that fire insurers should have $1 in surplus for every $1 of unearned premium reserve and that casualty companies should have $1 in surplus for every $2 in premiums written. This was known as the Kenney rule, after Roger Kenney, an insurance financial analyst who formalized the axiom in 1948. For a revised discussion of the original concept, see Roger Kenney, Fundamentals of Fire and Casualty Insurance Strength, 4th ed. (Dedham, Mass.: The Kenney Insurance Studies, 1967). The National Association of Insurance Commissioners' IRIS System (discussed in Chapter 6) suggests premium writings of three times policyholders' surplus.

11Property and liability insurance companies carry a Special Valuation Reserve for Liabilities, but this is not usually a liability account. Rather, it is an earmarked part of surplus.

12The general approach used in these modified reserving systems is similar. For example, one of the most direct approaches is the full preliminary term method, which uses the simple expedient of assuming that the policy is issued one year later for reserve purposes, thereby freeing the entire first-year premium (except the amount necessary to cover the policy's share of death claims) for the payment of expenses. For a more thorough discussion of the modified reserving systems, see any standard life insurance text.

13Technically, with most cat bonds, the insurer creates a special purpose vehicle (SPV) to issue the bond. The proceeds of the bond are placed in the SPV, and the SPV provides a reinsurance contract to the insurance company. This way, the bond proceeds are protected from the risk that the insurance company might become insolvent or use the bond proceeds for other purposes.

14Although the use of cat bonds introduces an element of basis risk absent from a traditional reinsurance contract, it eliminates the credit risk inherent in reinsurance contracts, that is, the risk that the reinsurer may not pay the claim. Because the bond issuer has the money, there is no risk that the funds won't be there to pay the issuer when a catastrophe covered by the bond occurs.

15While most insurance-linked bonds are aimed at transferring property catastrophe exposure, there are some exceptions. In 2005, AXA, a French insurer, issued bonds that would be triggered by a high loss ratio on its French motor insurance policies. Also in 2005, Oil Casualty Insurance, Ltd., had the first transaction that securitized liability risk when it issued bonds covering losses on its excess general liability book of business. Finally, Swiss Re issued bonds in January 2006 covering losses on its credit reinsurance business. See Securitization: New Opportunities for Insurers and Investors, Sigma No. 7/2006 (Swiss Reinsurance Company Economic Research & Consulting, Zurich, Switzerland, 2006).

16In longevity risk transfer, the payment to the investors decrease if the population lives longer. In Feb. 2013, for example, Aegon and Deutsche Bank announced a transaction to enable Aegon to transfer $12 billion Euros in longevity risk to the capital markets. The transaction was based on Dutch population data and enabled Aegon to hedge the longevity risk in its annuity business. Technically, the tranactions was accomplished through a “longevity risk swap” between Deutsche Bank and Aegon, with Deutsche Bank selling the securities to investors. For a discussion of longevity risk and regulatory issues, see Obersteadt, Ann, “Managing Longevity Risk,” NAIC Center for Insurance Policy and Research Newsletter, April 2013. Available at http://www.naic.org/cipr_newsletter_archive/vol7_managing_longevity_risk.pdf

17Specifically, the insurers have securitized their XXX reserves, which are required for certain term life insurance policies, and, more recently, AXXX reserves, which apply to universal life policies with guarantees. Typically, the insurer forms an SPV that issues a bond in the amount of the excess reserves. The reserves are reinsured by the SPV, and the proceeds from the sale of the bond provide the assets to support the reinsurance contract. Thus, the bond proceeds are backing the excess reserves, reducing the assets the insurer is required to hold. The need for these transactions will diminish when the NAIC's new principles-based reserving standard becomes effective.

18In 1997, the Bermuda Commodities Exchange (BCOE), which was incorporated in 1996, began trading insurance futures contracts and options. Like the CBOT, the BCOE offered members the opportunity to trade in option contracts based on an index of insured weather-related homeowners' losses in specific areas of the United States over specified periods of time. Like the CBOT it found inadequate market interest and suspended operations in 2000.

19Approximately $5 billion was raised to fund reinsurance sidecars in 2006, the most active year. While sidecars exist, they are less important today. Many experts believe they could regain importance in the aftermath of another major catastrophe.

20Hedge funds are investment funds, usually used by more sophisticated investors and institutions. Because they limit the eligible investors, they are exempt from many of the regulations that apply to mutual funds. Thus, they are able to use more investment strategies. The compensation of hedge funds is another distinguishing feature, with the hedge fund manager typically receiving a percentage of profits earned by the fund (e.g,. 20 percent). Hedge funds have been an important source of capital for reinsurers following major catastrophes.

21Although this example is based on the sale of stock, contingent capital agreements may allow the sale of debt or other securities (hybrid securities, which have characteristics of debt and equity).

22CCRIF participating countries are the following: Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Kitts & Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad & Tobago, Turks and Caicos Islands. In 2007, CCRIF paid nearly $1 miilion to the Dominican and St Lucian governments related to a 2007 earthquake in the eastern Caribbean. Turks & Caicos Islands received $6.3 million following Hurricane Ike in 2008, and Haiti received $7.75M as a result of a 2010 earthquake.

23Because the levying of taxes on the premium income of insurers required a registration and reporting system, the administrative taxation requirements had a great deal to do with the development of regulation by the states.