CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Distinguish between the two broad types of life insurance contracts

- Explain how the cash value arises in some life insurance contracts

- Distinguish between participating and nonparticipating life insurance contracts

- Explain the importance of renewability and convertibility features in term life insurance policies

- Describe the distinguishing characteristics of universal life insurance, adjustable life insurance, and variable life insurance

- Identify and describe the four major marketing classes of life insurance

- Describe the distinguishing features of group life insurance and explain the basis for its cost advantages

We begin our study of specific types of insurance with life insurance. We do this for two reasons. First, the life insurance policy is one of the simplest of all the insurance contracts. The insuring agreement is straightforward and to the point, there are relatively few exclusions, and the conditions and stipulations are easily understood.

In addition, we treat life insurance before the wide range of other insurance coverages that may be needed by individuals because many college students will soon be considering the purchase of life insurance, some even before graduation. By treating life insurance at this point, some students may avoid costly mistakes.

![]()

SOME UNIQUE CHARACTERISTICS OF LIFE INSURANCE

![]()

Life insurance is a risk-pooling plan, an economic device through which the risk of premature death is transferred from the individual to the group. However, the contingency insured against has certain characteristics that make it unique; as a result, the contract insuring against the contingency is different in many respects from other types of insurance. The event insured against is an eventual certainty. No one lives forever. Yet life insurance does not violate the requirements of an insurable risk for it is not the possibility of death that is insured but rather, untimely death. The risk in life insurance is not whether the individual is going to die but when, and the risk increases yearly. The chance of loss under a life insurance contract is greater in the second year of the contract, as far as the company is concerned, than it was in the first year and so on, until the insured dies. Yet through the mechanism of the law of large numbers, as we shall see, the insurance company can promise to pay a specified sum to the beneficiary no matter when death comes.

There is no possibility of partial loss in life insurance as there is in the case of property and liability insurance. Therefore, all policies are cash payment policies. In the event that a loss occurs, the company will pay the face amount of the policy.

![]()

Life Insurance Is Not a Contract of Indemnity

The principle of indemnity applies on a modified basis in the case of life insurance. In most lines of insurance, an attempt is made to put the individual back in the same financial position after a loss as before the loss. For obvious reasons, this is impossible in life insurance. The simple fact is we cannot place a value on a human life.

As a legal principle, every contract of insurance must be supported by an insurable interest, but in life insurance, the requirement of insurable interest is applied differently than in property and liability insurance. When the individual taking out the policy is the insured, there is no legal problem concerning insurable interest. The courts have held that every individual has an unlimited insurable interest in his or her own life and that a person may assign that insurable interest to any one. In other words, there is no legal limit to the amount of insurance one may take out on one's own life and no legal limitations as to whom one may name as beneficiary.1

The important question of insurable interest arises when the person taking out the insurance is someone other than the person whose life is concerned. In such cases, the law requires that an insurable interest exists at the time the contract is taken out. Many relationships provide the basis for an insurable interest. Husbands and wives have an insurable interest in each other as do partners. A corporation may have an insurable interest in the life of one of its executives. In most cases, a parent has an insurable interest in the life of a child although the extent of this interest may be limited by statute. A creditor has an insurable interest in the life of a debtor although this is usually confined by statute to the amount of the debt or slightly more.

The question of insurable interest seldom arises in life insurance because most life insurance policies are purchased by the person whose life is insured. In addition, the consent of the individual insured is required in most cases even when there is an insurable interest. The exception to this requirement exists in certain jurisdictions where a husband or wife is permitted to insure a spouse without the other's consent.

![]()

TYPES OF LIFE INSURANCE CONTRACTS

![]()

Based on their distinguishing characteristics, six distinct types of life insurance contracts exist: (1) term, (2) whole-life, (3) endowment, (4) universal life, (5) variable life, and (6) variable universal life. Term insurance, whole-life, and endowment contracts were the traditional forms of life insurance and have existed for many years. Universal life, variable life, and variable universal life insurance contracts are more recent innovations, and date from the 1970s and early 1980s. Ignoring the subtle differences among some of these types of policies for the moment, we can divide life insurance products into two classes: those that provide pure life insurance protection, called term insurance, and those that include a savings or investment element, which we will call cash value policies. Based on this classification system, life insurance products are divided into two classes:

Although the policies we have classified as cash value policies differ, these contracts are more similar than they are different. Later in the chapter, we will discuss the distinguishing characteristics of these contracts, but for the moment, let us focus on the difference between term insurance, which provides pure insurance protection, and cash value life insurance, which combines insurance with a saving element. Because whole-life insurance is the prototype cash value contract, it can serve as a representative in our discussion for cash value policies generally.

![]()

Reasons for Difference in Term and Cash Value Insurance

As a point of departure, let us examine the distinctions between policies that provide pure protection and those that combine insurance with an investment.

The simplest form of life insurance is yearly renewable term. This type provides protection for one year only, but it permits the insured to renew the policy for successive periods of one year at a higher premium rate each year, without having to furnish evidence of insurability at the time of each renewal. This is life insurance protection in its purest form.

The easiest way to understand the operation of any mechanism is to try it. In life insurance, as in other forms of insurance, the fortunate many who do not suffer loss share the financial burden of the few who do. In life insurance, each member of the group pays a premium that represents the member's portion of the benefit to be paid to the beneficiaries of those who die. Mortality data tell us that at age 21, 0.48 out of every 1000 females will die.2 To simplify the mathematics, let us assume that there are 100,000 females in the group. On that basis of past experience, we may expect 48 of them to die. If we wish to pay a death benefit of $1000 to the beneficiary of each woman who dies, we will need $48,000. Ignoring, for the present, the cost of operating the program and any interest that we might earn on the premiums we collect, and assuming that the mortality table is an accurate statement of the number who will die, we will need to collect $0.48 from each individual in the group to provide the needed $48,000.3 During the years, 48 members of the group will die and $48,000 will be paid to their beneficiaries.

The next year, we would find that the chance of loss has increased, for all members of the group are older, and past experience indicates that a greater number will die per 1000. At age 24, it will be necessary to collect $0.54 from each member. At age 30, the cost will be $0.68. At age 40, the cost per member will have almost tripled from the cost at age 21, and it will be necessary to collect $1.30. By the time the members of the group reach age 40, we will have to collect $3.08 from each. At age 60, we will need $8.01, and at age 70, we will need $17.81 from each member. It does not take a great deal of insight to recognize that, before long, the plan is going to bog down if it has not done so before the member reaches age 70. At age 70, when the probability of death is greater than before, the members may find that they cannot afford the premium that has become necessary. At age 80, we will need $43.86 from each member, and at age 90, $121.92. At age 100, we will need $275.73. The increasing mortality as the group grows older makes yearly renewable term impractical as a means of providing insurance at advanced ages. Yet, many insurance buyers want coverage that continues throughout their lifetime. Insurers have found a practical solution.

![]()

The Level Premium Concept

A practical method of providing life insurance for the entire lifetime of the insured is to use a level premium. The whole-life insurance policy was the original type of lifetime policy. It provides protection at a level premium for the entire lifetime of the insured. This lifetime protection is possible because the premium is set at a level that is higher than necessary to fund the cost of death claims during the early years of the policy, and the excess premiums are used to meet the increasing death claims as the insured group grows older.

The level premium for an ordinary life policy of $1000 purchased by a female at age 21 and the one for yearly renewable term insurance beginning at age 21 are illustrated in Figure 12.1. The line that constitutes the level premium is the exact mathematical equivalent of the yearly renewable term premium curve. This means that the insurance company will obtain the same amount of premium income and interest from a large group of insureds under either plan, assuming that neither group discontinues its payments.

The level premium plan introduces features that have no counterpart in term insurance. From a glance at Figure 12.1, it is clear that under the level premium plan, the insured pays more than the cost of pure life insurance protection during the early years the policy is in force. This overpayment is indicated by the difference between the term and the level premium lines up to the point at which the lines cross. The overpayment is necessary so the excess portion, when accumulated at compound interest, will be sufficient to offset the deficiency in the later years of the contract. The excess payments during the early years of the contract create a fund that is held by the insurance company for the benefit and credit of the policyholders. The fund is invested, usually in long-term investments, and the earnings are added to the accumulating fund to meet the future obligations to the policy-holders. The insurer establishes a reserve or liability on its financial statement to reflect these future obligations.

FIGURE 12.1 Comparison of Net Premiums per $1000 Yearly Renewable Term and Whole Life

Again from Figure 12.1, it appears that the reserve should increase for a time and then diminish. It also appears the area of redundant premiums in the early years of the contract will always be insufficient to equal the inadequacy in the later years. In the case of a single individual, this would be true, but many insureds are involved, and the law of averages permits a continuously increasing reserve for each policy in force. Some insureds will die during the early years of the contracts, and the excess premiums they have paid are forfeited to the group. The excess premiums forfeited by those who die, together with the excess premiums paid by the survivors, will offset the deficiency in later years and, with the aid of compound interest, will continue to build the reserves on the survivors' policies until they equal the face of the contract at age 100. Death is bound to occur at some time, and in a whole-life policy, the insurance company knows that a death claim must ultimately be paid.4 Aggregate reserves for the entire group of insureds increase and then decrease, but individual policy reserves continue to climb, mainly because the aggregate reserves are divided among a smaller number of survivors each year. Figure 12.2 shows the growth in the reserve on an ordinary life policy purchased at age 21.

FIGURE 12.2 Increase in Reserve on Whole-Life Policy

The level premium plan introduces the features of the redundant premium during the early years of the contract and the creation of the reserve fund. The insured has a contractual right to receive a part of this reserve in the event the policy is terminated, under a policy provision designated the non-forfeiture value (discussed in Chapter 15). The contractual right to receive a part of the excess premiums paid under the level premium plan, therefore, represents an investment element in the contract for the insured. When a policyholder dies, the death benefit could be viewed as being composed of two parts—the portion of the reserve to which the insured would have been eligible and an amount of pure insurance. Under this view, the face amount of the policy is seen as a combination of a decreasing amount of insurance (the net amount at risk) and the increasing investment element (the growing reserve). The decreasing insurance and the increasing investment element always equal the face amount of the policy.

The policy reserve is not solely the property of the insured. It is the insured's only if and when the policy is surrendered. If this occurs, the contract no longer exists, and the insurance company is relieved of all obligations on the policy. As long as the contract is in full force, the reserve belongs to the insurance company and must be used to pay the death claim if the insured should die. As mentioned, the reserve must be accumulated by the company to take care of the deficiency in the level premium during the later years of the contract.

The preceding analysis suggests that the use of level premium insurance has two distinct advantages. First, by paying an amount in excess of the cost of pure life insurance during the early years of the contract, the insured avoids a rising premium in the later years; this will make it financially possible to maintain the insurance until the policyholder's death even though it occurs at an advanced age. Second, if the insured survives, he or she has accumulated a savings fund that can be used for income in old age (or any other purpose the insured decides).

![]()

TAX TREATMENT OF LIFE INSURANCE

![]()

The accumulating fund that arises from the overpayment of premiums and the insured's right to withdraw the cash values based on these overpayments adds an investment element to the protection function of life insurance. Before continuing with our discussion, let us pause to examine the way in which this investment element and life insurance are treated for tax purposes.

Life insurance policies are granted favorable tax treatment in two ways. First, amounts payable to a beneficiary at the death of an insured are generally not included in taxable income.5 In addition, income earned on the cash surrender value of life insurance policies is not taxed currently to the policyholder. The investment gain on a life insurance policy is taxed at the termination of the contract prior to death only to the extent that the cash value exceeds the policyholder's investment in the contract (i.e., the sum of all premiums paid on the contract). Because the total amount of premiums paid includes the cost of life insurance protection, this represents an understatement of the taxable gain. Both features of this tax treatment are obviously beneficial to the insured or beneficiaries. Given the favorable treatment of the investment return arising from life insurance cash values, it was probably inevitable that entrepreneurial ingenuity would find a way to exploit that tax treatment. Over time, new forms of life insurance with greater overpayments were developed to take advantage of the favorable tax treatment. It was also probably inevitable that Congress would question whether the tax treatment of life insurance created unintended loopholes in the tax system. The issue arose because, although the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) granted favorable tax treatment to life insurance, there was no statutory definition of the term life insurance. Congress concluded that the absence of a definition of life insurance allowed some products that were designed primarily as investment instruments to shelter what would otherwise be taxable income because the products were called life insurance. Congress, therefore, sought to construct a definition of life insurance that would preserve the favorable tax treatment of those instruments that are life insurance but deny it to contracts that are investment instruments.

If the contract fails to meet the definition of life insurance at any time, the pure insurance portion of the contract (the difference between the face amount and the cash surrender value) will be treated as term life insurance. The cash surrender value will be treated as a deposit fund, and income earned on the fund will be taxable. In addition, all income previously deferred will be included in the insured's income in the year the contract fails to qualify as a life insurance contract. The new definition of life insurance generally applies to policies issued after 1984.

![]()

Code Definition of Life Insurance

The 1984 act contains two tests for determining whether a contract is a life insurance contract. One test deals with a cash value accumulation; the second involves a guideline premium test and a cash value corridor test. Regardless which test is selected for a contract, it must be satisfied at all times for the life of the contract. Both tests are designed to limit the types of contracts that qualify as life insurance to those contracts that involve only a modest investment and yield a modest investment return.

The cash value accumulation test will be met if the cash surrender value of the contract at any time does not exceed the net single premium that is required to fund future benefits, assuming the contract matures no earlier than age 95.6 In general, the net single premium for this test is computed using the greater of a 4 percent annual effective rate of interest or the rate guaranteed when the contract is issued.

The second test has two requirements that must be met: a guideline premium test and cash value corridor test. A contract can satisfy the guideline premium test if the sum of the premiums does not exceed the greater of two limitations: the guideline single premium or the sum of the guideline level premiums. The guide-line single premium must use the greater of a 6 percent annual interest rate or the rate guaranteed when the contract is issued. The guideline level premium is the amount, over a period that does not end before age 95, necessary to fund future benefits. In effect, the guideline premium tests eliminate from the definition of life insurance those policies with premiums greater than the amount required to fund the contract's death benefits.

The net single premium, guideline single premium, and guideline level premium must be calculated using reasonable mortality charges, which cannot exceed the mortality charges specified in the prevailing commissioners standard table at the time the contract was issued. Prior to 2004, the prevailing standard was the 1980 CSO Mortality Table. In 2004, the 2001 CSO Mortality Table became the prevailing standard, after 26 states had adopted it. Federal law provides a transition period for moving to a new mortality standard. In November 2006, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) announced that use of the 2001 CSO tables would be mandatory for any contracts issued after 2008. This has had the result of reducing the amount of cash value permitted for a given level of life insurance protection.

The cash value corridor test is designed to disqualify any contract that builds up excessive amounts of cash value in relation to the life insurance risk. The cash value corridor test will be satisfied if the death benefit at any time is more than a percentage (supplied in the table contained in the 1984 act) of the cash surrender value. In general, the applicable percentages begin at 250 percent for an insured 40 years of age or younger and decrease to 100 percent for an insured 95 years of age (see Table 12.1).

TABLE 12.1 Percentages for Corridor Test

When the values in the table are applied, the applicable percentage is decreased by a ratable portion for each full year. For each age bracket, the percentage is decreased by the same amount for each year in that bracket. For example, for the 55-year-old to 60-year-old age bracket, the applicable percentage falls from 150 to 130 percent, or four percentage points for each annual increase in age. At age 57, the applicable percentage will be 142 (150 minus 8).

![]()

CURRENT LIFE INSURANCE PRODUCTS

![]()

Now that we have an idea about why term insurance differs from cash value life insurance, we can take a closer look at some of those differences as they are reflected in the insurance products from which consumers can choose. We will begin this examination by returning once again to term insurance.

![]()

Term Insurance

We know that term insurance provides temporary protection. It is called term because the coverage is for a limited term. The period for which the coverage will be provided may be 1 year, 5 years, 10 years, or 20 years. It may be term to expectancy, which is term insurance for the period the insured is expected to live, according to the mortality tables.

In its purest form, a term policy is purchased for a specified time period and the face amount is payable only if the insured dies during this period. Nothing is paid if the insured survives the term period. It is customary, however, for term policies to include provisions relating to renewability and convertibility.

Renewable Term Renewable-term policies include a contractual provision guaranteeing the insured the right to renew the policy for a limited number of additional periods, each usually of the same length as the original term period. For example, if the insured purchases a 10-year term policy at age 25 and survives this period, he or she has the option of renewing the policy for an additional 10 years without having to prove insurability. The level premium for this 10-year period will be higher than that for the first 10 years because of the insured's more advanced age. The insured may renew the policy at age 45 and perhaps at age 55. However, most insurance companies, because of the element of adverse selection, impose an age limit beyond which renewal is not permitted. A limited number of companies offer term policies that are renewable to age 100.

Convertible Term The conversion provision grants the insured the option to exchange the term contract for some type of permanent life insurance contract without having to provide evidence of insurability. The options to renew regardless of insurability and to convert without evidence of insurability provide the insured with complete protection against loss of insurability.7 The conversion is usually effected at the policyholder's attained age, but it can be made retroactive to his or her original age. For example, if the insured decides to convert the term policy to whole life at age 32, and to convert at the attained age, the premium on the whole-life policy will be the same as if it had been purchased at age 32, which it is. However, the policy can be converted at the original age of 25, and the premium rates on the converted policy will be those the insured would have paid if the whole-life policy had originally been purchased at age 25. However, the insured will be required to pay a lump sum to the insurer that is sufficient to bring the reserve on the converted policy to the level it would have reached if originally purchased at age 25.

The right of conversion was almost a universal trait of term policies, but this is no longer the case. As price competition in term insurance has intensified, some insurers have determined that by eliminating the conversion privilege, or limiting it to the first five years of the policy, they can offer a lower-priced term product. The consumer should, of course, weigh the lower price of these products against the absence of convertibility.

Variations in Renewal and Conversion Privileges Renewal and conversion provisions and the premium structure in term policies may be combined in a variety of ways, creating a myriad of different contracts. Many term policies permit renewal for another period at a level premium. Some term policies that start off with a level premium for 5, 10, or 20 years become annually increasing premium policies after that initial period. Still other policies have a reentry provision that allows the insured to requalify through a somewhat abbreviated underwriting process and continue the policy at a relatively low rate. If the insured does not qualify, he or she may keep the policy but at a higher premium. Often, this premium is a multiple of the prior premium and is a guaranteed maximum that is stated in the policy. Because these subtle variations in renewability and conversion privileges can produce significant differences in protection and cost, they are important considerations in the selection of term insurance products. Understanding the differences among apparently similar contracts is a requisite for an informed decision.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Term Insurance The advantages and disadvantages of term insurance stem from its dual character as pure protection and temporary protection. With respect to term's nature as pure protection, because the premium for term insurance covers protection only, term insurance provides the greatest amount of protection for a given dollar outlay. Because it is temporary protection, it may be better suited to meet temporary insurance needs than permanent insurance would be.

As in the case of its advantages, the disadvantages of term insurance stem from its nature as pure protection and temporary protection. Term insurance is misused when it is used to meet permanent needs. In addition, because insurers are subject to a greater element of adverse selection in term policies than in policies that include an investment element, the cost of term insurance may be somewhat greater than the cost of death protection in permanent insurance.

![]()

Whole-Life Insurance

In our discussion of the difference between term insurance and cash value insurance, we used the whole-life policy as the representative of cash value-type contracts. This seems appropriate, since the whole-life policy is the standard approach to permanent insurance, and other cash value policies may be described in terms of the way(s) in which they differ from whole life.

Straight Whole Life The term straight whole life refers to a contract in which the premiums are payable for the entire lifetime of the insured. It is also called continuous premium whole life.

The principal advantage of straight whole life is that it provides permanent protection for permanent needs and can be continued for the entire lifetime of the insured. In addition, because it includes a cash value, it serves the dual function of protection and saving. The savings element in the policy can be borrowed for emergencies, or it can be used to pay future premiums under the policy.

Straight whole life has disadvantages when it is used to fill a need for which it was not designed. When it is used to meet a temporary need, the amount of coverage that may be purchased may be less than if the need were met with term insurance. Conversely, there are permanent life insurance needs, and permanent insurance should be used to meet such needs. Insurance to provide liquidity for estate tax purposes, for example, is a permanent need that cannot be met by temporary life insurance contracts such as term insurance.

Limited-Payment Whole Life Limited-payment (limited-pay) whole life is a variation of the whole-life policy, differing only in the manner in which the premium is paid. As in the case of a straight whole-life policy, protection under the limited-pay whole-life policy extends for the whole of life, but the premium payments are made for some shorter period of time. During the period that premiums are paid, they are sufficiently high to prepay the policy. Thus, under a 20-payment life policy, during the payment period, one pays premiums that are high enough to permit one to stop payment at the end of 20 years and still enjoy protection equal to the face amount of the policy for the remainder of one's life.

![]()

Universal Life Insurance

Universal life (UL) insurance was introduced in 1979 by Hutton Life, a subsidiary of the stock-brokerage firm E. F. Hutton. The essential feature of universal life, which distinguished it from traditional whole life, is that, subject to specified limitations, the premiums, cash values, and level of protection can be adjusted up or down during the term of the contract to meet the owner's needs. A second distinguishing feature is that the interest credited to the policy's cash value is geared to current interest rates but is subject to a minimum such as 4 percent.

In effect, the premiums under a universal life policy are credited to a fund (which, following traditional insurance terminology, is called the cash value), and this fund is credited with the policy's share of investment earnings after the deduction of expenses. This fund provides the source of funds to pay for the cost of pure protection under the policy (term insurance), which may be increased or decreased, subject to the insurer's underwriting standards. Universal policyholders receive annual statements indicating the level of life insurance protection under their policy, the cash value, the current interest being earned, and a statement of the amount of the premium paid that has been used for protection, investment, and expenses.

Some insurers set the minimum amount of coverage for their universal life products at $100,000; other companies offer contracts with an initial face amount as low as $25,000. As in the case of other forms of permanent insurance, the policyholder may borrow against the cash value, but in the case of universal life, he or she may also make withdrawals from the cash value without terminating the contract.

To understand the excitement that universal life insurance brought to the insurance market when it was introduced, recall that interest rates in this country reached a historic high in the early 1980s. The high rates of interest that were credited to UL cash values, combined with the favorable tax treatment and the ability to withdraw a part of the cash value (as opposed to borrowing against the cash value), enhanced the contract's appeal. Universal life enjoyed a phenomenal growth throughout the 1980s.

Universal life received a warm response in the insurance market when it was introduced; this was primarily a result of timing. It was not an accident that UL products were first offered during the era of record-level interest rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Investors who purchased universal life policies in 1982, when the rate on money market funds reached 15 percent, thought that these rates would go on forever. They were wrong. When interest rates fell, so did the performance of UL policies. Many insureds who had been mesmerized by unrealistic projections had purchased the policies with the expectation that the investment earnings would pay future premiums. When the investment earnings on the policy fell short, the insureds were compelled to pay unexpected premiums to continue their coverage.

The market share of UL insurance fell in the late 1990s but has been growing again in recent years, reaching 40 percent of new sales by 2012. The market share of whole-life insurance, in contrast, has fallen from 82 percent of life insurance sales in 1980 to 32 percent of sales in 2012 (based on first-year premiums).

![]()

Variable Life Insurance

Variable life insurance is a whole-life contract in which the insured has the right to direct how the policy's cash value will be invested and the insured bears the investment risk in the form of fluctuations in the cash value and in the death benefit. Variable life is patterned after the variable annuity, which has been available to groups since 1952 and to individuals for over a decade.8 Like the variable annuity, variable life is designed as a solution to the problem of the decline in the purchasing power of the dollar that accompanies inflation. Early variable life insurance policies were patterned after the so-called ratio plan, a concept originally suggested by New York Life. Under this plan, the amount of the premium was fixed, but the face amount of the policy varied, subject to a minimum, which was the original amount of insurance. The cash value of the policy was not guaranteed and fluctuated with the performance of the portfolio in which the premiums had been invested by the insurer. This fluctuating cash value provided the funds to pay for the varying amount of death protection. Some insurers offered policyholders a choice of investments, with the underlying fund invested in stock funds, bond funds, or money market funds.

Although variable life policies have been available in other countries for some time,9 this type of insurance developed slowly in the United States, largely because of the regulatory conflicts that had accompanied the emergence of the variable annuity. Although the NAIC approved model legislation providing for the sale of variable life policies in 1969 and recommended this legislation to the states, there remained the problem of the equity-based nature of the contract and the qualification requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). In 1972, seeking to avoid some of the difficulties that had been encountered in connection with the variable annuity, the insurance industry petitioned the SEC for an exemption on variable life. After conducting hearings, the SEC ruled that variable life would be treated as a security.10 This meant that variable life policies could be sold only by agents registered as broker-dealers with the National Association of Securities Dealers (now FINRA).

Variable Universal Life Most variable life insurance policies sold today are structured as variable universal life insurance (VUL). It combines the flexible premium features of universal life with the investment component of variable life. The policyholder decides how the fund will be invested, and the fund's performance is directly related to the performance of the underlying investments.

In 2012 variable universal life insurance represented about 7 percent of new sales, based on first-year premiums.

![]()

Adjustable Life Insurance

Adjustable life insurance was introduced in 1971 and predates universal life insurance. It was the first version of modern flexible premium policies. Since the development of universal life insurance, adjustable life insurance has diminished in importance although some policies purchased in the 1970s are still in force.

Like universal life insurance, an adjustable life policy allows the buyer to adjust various facets of the policy over time as the need for protection and the ability to pay premiums change. Within certain limits, the insured may raise or lower the face amount of the policy and may increase or decrease the premium over the life of the policy.

Adjustable life insurance differs from universal life insurance in several ways. First, changes in the premium of an adjustable life policy are more structured than is the case with universal life insurance. The insurer must be notified of the proposed change, and once the change is made, the new premium must be paid until another formal change is made. In universal life, the premiums can vary according to the preference of the insured without prior notification to the insurer. In addition, in a universal life policy, the investment and protection elements are unbundled, and the insured receives annual reports concerning investment income, mortality cost, and other expenses. This transparency is absent in adjustable life insurance.

![]()

Endowment Life Insurance

Although endowment policies were one of the victims of the changes in the tax code enacted in 1984, our discussion of life insurance policies would be incomplete without at least a brief mention of these contracts.

Under endowment life policies, which, like term insurance, are issued for a period such as 10 years or 20 years, the insurer promises to pay the face of the policy if the insured dies during the policy period and promises to pay the face of the policy if the insured survives until the end of the period. (“You win if you live and you win if you die.”) Endowment policies are investment instruments that combine a pure endowment with a death benefit.11 Because they require premiums far in excess of the amount required to fund the death benefit, they do not qualify as life insurance under the current provisions of the tax code.

![]()

Participating and Nonparticipating Life Insurance

Before leaving our discussion of the types of life insurance policies, we should note an additional differentiation among life insurance policies: the distinction between participating and nonparticipating types. A participating policy is one on which annual dividends are paid to the policyholder. Originally, such policies were issued only by mutual life insurers, but many stock life insurers now offer them. Under a participating policy, a substantial margin of safety is built into the premium, sufficient to reflect a willful overcharge but justified on the assumption that if the extra premium is unneeded, it will be returned to the policyholder as a dividend.

Because of the long-term nature of life insurance contracts, companies must calculate premium charges under traditional policies on a conservative basis. Once the premium rate on traditional policies is established, it must be guaranteed for the entire policy. It cannot be altered even if the basic factors used in the computation change considerably. Over a long period, shifts in the premium factors could occur: Mortality rates may change; the expenses of operating the company may increase, particularly if the long-run trend of prices is upward; and interest rates may change, down or up. If the current premium rates are to be sufficient to enable insurers to fulfill their obligations on contracts that may continue for many decades in the future, a safety margin must be used in calculating the premium. The participating concept permits the insurer to establish a more generous margin in the form of an intentional overcharge, which will be returned to the policyholder if unneeded. The safety margin on nonparticipating policies is narrower because the cost of the insurance to the policyholder cannot be adjusted at a later time. The gross premium charged on nonparticipating policies must reflect, at least for competitive reasons, the cost of providing the insurance. Any profit realized in the operation will be used to provide dividends to stockholders as well as surplus funds that may be used as a buffer for future adverse experience.

![]()

GENERAL CLASSIFICATIONS OF LIFE INSURANCE

![]()

There are three main classes of life insurance, distinguished by the manner in which they are marketed:

- Individual life insurance

- Group life insurance

- Credit life insurance

![]()

Individual Life Insurance

Individual life insurance is sold to individuals, typically through life insurance agents.12 Premiums are paid annually, semiannually, quarterly, or monthly. Individual life insurance currently accounts for 54 percent of all life insurance in the United States. The average face amount for newly purchased individual policies in 2011 was $162,000.*

![]()

Group Life Insurance

Group life insurance is a plan in which coverage can be provided for a number of persons under one contract, called a master policy, usually without evidence of individual insurability. It is generally issued to an employer for the benefit of employees but may be used for other closely knit groups. The individual members of the group receive certificates as evidence of their insurance, but the contract is between the employer and the insurance company. Group life insurance programs sponsored by an employer may be contributory or noncontributory. Under a contributory plan, which is the more common approach, employer and employees share the cost of the insurance. Under a noncontributory plan, the employer pays the entire cost.

In most states, the groups to which group life insurance may be issued are defined by laws patterned after an NAIC Model Group Life Insurance Law. The NAIC Model Group Life Insurance Law definition includes the following six groups:

- Current and retired employees of one employer

- Multiple employer groups

- Members of a labor union

- Debtors of a common creditor

- Members of associations formed for purposes other than to obtain insurance, provided the association has at least 100 members and has been in existence for at least two years

- Members of credit unions

In addition to these standard groups defined in the NAIC model law, some state laws authorize “any other group approved by the commissioner,” generally referred to as discretionary groups. The requirements for the first six groups are defined in the law, and no specific permission is required for the purchase of insurance by such groups. Discretionary groups require specific approval by the insurance commissioner, which will be granted only if the proposed coverage meets a balancing test set forth in the law. Generally, the laws state that the commissioner will approve such groups if the plan meets three conditions. First, the issuance of the group policy must be judged not contrary to the best interest of the public. Second, the issuance of the group policy will result in economies of acquisition or administration costs. Finally, the benefits under the group policy must be reasonable in relation to the premium charged.

The basic feature of group life insurance is the substitution of group underwriting for individual underwriting. This means there is no physical examination or other individual underwriting methods applicable to individual employees. The major problem of the insurance company is, therefore, that of holding adverse selection to a minimum, and many of the features of group life insurance derive from this requirement. For example, when the premium is paid entirely by the employer, 100 percent of the eligible employees must be included. When the plan is contributory, with the premium paid jointly by the employer and the employees, more than 75 percent of the eligible employees must participate. Furthermore, the amount of insurance on each participant must be determined by some plan that will preclude individual selection. In most instances, the amount of insurance is a flat amount for all employees, or it is determined as a percentage or multiple of the individual's salary. If group life insurance were provided without any required minimum number or percentage of employees, and if the employees could choose to enter the plan or stay out, a disproportionate number of impaired individuals would subscribe to the insurance. If the employee could choose the amount of insurance, the impaired lives would tend to take large amounts while those in good health would opt for only small amounts. For group insurance to be practical, safeguards must be provided to prevent and minimize the element of adverse selection.

The cost of group life insurance is comparatively low for the following reasons. First, the basic plan under which most group life insurance is provided is yearly renewable term insurance, which provides the lowest cost form of protection per premium dollar. For employer-sponsored plans, the flow of insureds through the group maintains a stable average age as older employees retire, die, or leave the firm and their places are taken by younger workers. In addition, the expenses of medical examinations and other methods of determining insurability are largely eliminated. Third, group life involves mass selling and administration, with the result that expenses per life insured are less under group policies than under the marketing of individual policies. Finally, when group life insurance is part of an employee's compensation, tax advantages reduce the cost. Under current federal tax laws, an employer may deduct as a business expense premiums on group term life insurance up to $50,000 per employee, and amounts paid by the employer for such insurance are nontaxable as income to the employee. This means the employees would have to receive something more in salary than the amount paid by the employer for the insurance to purchase an equivalent amount of life insurance individually.13

The coverage under group life insurance contracts is generous. There are no exclusions, and the insurance proceeds are paid for death from any cause, including suicide, without restrictions as to time. In addition, most policies include a conversion provision, under which the insured employee may, within 31 days after termination of employment, convert all or a portion of the insurance to any form of individual policy currently offered by the insurance company, with the exception of term insurance. Conversion is at the attained age of the employee and cannot be refused by the insurance company because of the worker's uninsurability.

Although the original group idea was to substitute group underwriting and group marketing for individual underwriting and marketing, group underwriting has changed somewhat since the beginning of group life insurance. Under the first group life insurance laws, the definition of groups for insurance purposes were restrictive, requiring a minimum number of members, usually 50 or 100 lives.14 Over time, statutory requirements concerning the minimum number of individuals in a group have shrunk, and with the decrease in the number, the nature of group underwriting has changed. As the minimum number of members required for group coverage fell, insurers introduced elements of individual underwriting for smaller groups. Although group underwriting is still used for large groups, state laws often allow insurers the right to require evidence of individual insurability on groups. Whether an insurer will require evidence of individual insurability for group coverage depends on the size and nature of the group.

Group life insurance has become an important branch of life insurance today, accounting for over 40 percent of all such protection in force in 2011. For many persons who would not be insurable under individual life insurance, it provides the only means for obtaining coverage. For others, the low-cost group life insurance is an excellent supplement to the individual life insurance program.

![]()

Credit Life Insurance

Credit life insurance is sold through lending institutions to short-term borrowers contemplating consumer purchases and through retail merchants selling on a charge account basis to installment buyers. It includes mortgage protection life insurance of 10 years'duration or less that is issued through lenders.15 The insurance protects the lenders and debtors against financial loss should the debtor die before completing the required payments. The life of the borrower is insured for an amount related to the outstanding balance of a specific loan, and the policy generally provides for the payment of the scheduled balance in the event of the debtor's death. The insurance is term insurance, decreasing in amount as the loan is repaid. The major suppliers of credit life insurance, and the lenders who are usually involved as vendor beneficiaries of this coverage, include commercial banks, sales finance companies, credit unions, personal finance companies, and retailers selling goods and services on a charge account or installment basis. Some companies specialize in writing credit life, whereas for other insurers, it represents only a small part of their total business. The coverage is sold on an individual and a group basis. In the former, borrowers receive individual policies. In the latter, a master policy is issued to the lending institution, and the individual borrowers receive certificates outlining their coverage. Approximately 85 percent of the credit life insurance is written on a group basis.

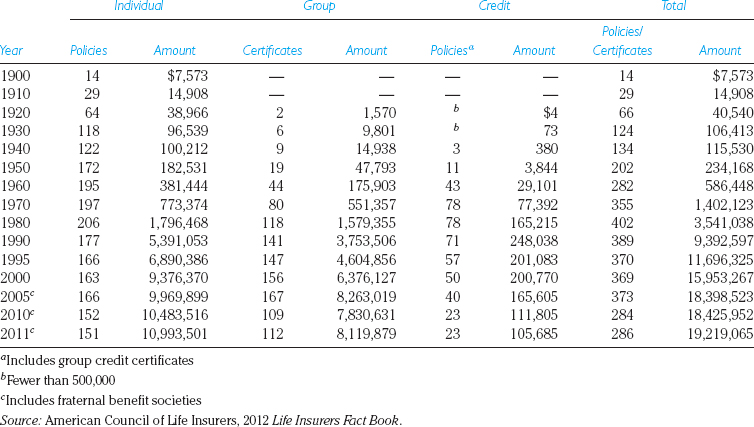

TABLE 12.2 Life Insurance in Force in the United States, by Year (policies and certificates in millions/amounts in millions)

Although credit life insurance was introduced in 1917, its growth was modest until the end of World War II. After 1945, it grew rapidly, closely paralleling the increase in consumer debt. From an insignificant $365 million in coverage in 1945, it had increased to about $166 billion, or about 0.9 percent of total life insurance in force by the end of 2005. Evidence of its growing significance is that only about 7 percent of all outstanding consumer credit was protected by credit life inusrance in 1945, but by 2000, the percentage had climbed to more than 80 percent.

The amount of credit life insurance in force began to decline in 2006, with a rapid decrease beginning in 2009, accompanying the decrease in overall household debt that followed the financial crisis. By year-end 2011, the amount of credit life insurance had fallen to about $106 billion or 0.55 percent of total life insurance in force.

![]()

Total Life Insurance in Force in the United States

Total commercial life insurance in force at the end of 2011 exceeded $19 trillion. More than 97.5 percent was issued by stock or mutual life insurance companies, and the remainder was written by fraternal societies and other private insurers.16 Over time, the percentage of life insurance written by stock insurers has grown, reflecting the wave of demutualizations during the 1990s and early 2000s. Table 12.2, which lists the insurance in force with commercial life insurance companies from 1900 through 2011, indicates the distribution of the insurance by class and depicts its growth and changing distribution over time.

![]()

Other Types of Life Insurance

In addition to the life insurance issued by legal reserve life insurance companies, a small amount is written by other types of insurers.

Wisconsin State Life Insurance Fund The Wisconsin State Life Insurance Fund issues policies with a $1000 minimum and a $10,000 maximum to persons in the state at the time of issuance. Although the program has been in effect since 1911, the total amount of insurance under the program is less than 1 percent of all life insurance in the state.

Veterans' Life Insurance The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has sold life insurance to veterans since World War I, and the total amount of government life insurance in force under these programs was about $12.9 billion at the end of 2011. Most of the programs are closed to new entrants. The two that remain open, the Service-Disabled Veterans Insurance Program and the Veterans' Mortgage Life Insurance Program, are designed for individuals with service-related disabilities.17

In addition to the veterans' life insurance programs in which the government acts as the insurer, there are two other programs supervised by the Veterans Administration and subsidized by the federal government: the Servicemen's Group Life Insurance (SGLI) Program and the Veterans' Group Life Insurance (VGLI) Program. However, these are underwritten by the private insurance industry.

Members of the U.S. military, including cadets and midshipmen at the service academies, are automatically insured under the SGLI Program for $100,000. Service members who wish to do so, may elect in writing to be covered for a lesser amount, or may elect not to be covered at all. A related program, SGLI Family Coverage, provides coverage for spouses and dependent children of those covered by SGLI. Total life insurance in force under the two programs was over $1.2 trillion in 2011.

SGLI may be converted to five-year renewable term coverage under the VGLI Program. Coverage is limited to the amount the service member had at the time of separation and may be continued in increments of $10,000 from $10,000 to $200,000. The VGLI Program may be renewed for an additional five-year term at the end of each five-year term, or it may be converted to an individual permanent life insurance policy without evidence of insurability.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

term insurance

cash value life insurance

net premium

gross premium

level premium

policy reserve

nonforfeiture value

transfer for value

guideline premium test

cash value corridor test

term to expectancy

renewable term

convertible term

yearly renewable term

straight whole-life insurance

limited-pay whole-life insurance

universal life insurance

variable life insurance

variable universal life insurance

adjustable life insurance

endowment life insurance

pure endowment

participating life insurance

nonparticipating life insurance

policy dividend

group life insurance

credit life insurance

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. Distinguish between term insurance policies and cash value policies.

2. Explain what is meant by the statement that term insurance is pure protection.

3. Under a whole-life policy, the overpayment by the insured during the early years of the contract offsets underpayments in later years. This being the case, the reserve should reach a peak and then gradually decline. How do you explain the fact that it does not?

4. Under a whole-life policy, the amount payable in the event of the insured's death can be viewed as consisting of two parts. Explain this concept.

5. Describe the ways in which life insurance policies receive favorable tax treatment.

6. John Jones buys a renewable, convertible, nonparticipating term insurance policy. Explain the precise meaning of each of the italicized words.

7. Describe the distinguishing characteristics of universal life, variable life, and variable universal life insurance.

8. What is the difference between a participating and a nonparticipating life insurance contract? How do their premiums reflect this difference?

9. Life insurance may be classified according to the manner in which it is marketed. Identify the three classes of insurance based on this classification and explain the distinguishing characteristics of each.

10. Distinguish between individual and group life insurance arrangements, and identify the sources of the cost advantage for group life insurance.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. To what extent are the proceeds of a life insurance policy exempt from the claims of the creditors of the beneficiary? On what basis can such exemptions be justified?

2. The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) provides certain tax advantages to life insurance. Some observers argue that this gives life insurance an unfair advantage over other savings vehicles, such as mutual funds. Do you agree or disagree? Why?

3. The life insurance policy reserve arises because of the overpayment of premiums in the early years of the policy. When a policy lapses, state laws require that the insurer return a part of that overpayment to the policyholder as a nonforfeiture benefit. There are other policies in which a similar cost and premium structure exists, but insurers are not required to provide nonforfeiture benefits if the policy lapses. For example, long-term care insurance (discussed in Chapter 22) is typically written without nonforfeiture benefits. Do you think insurers should be required to pay nonforfeiture benefits for these policies? Why or why not?

4. Dividends paid to policyholders on participating policies are treated by the IRS as a return of premium and are not subject to income tax. Dividends to shareholders in a stock company, however, are taxable income to the recipients. Do you believe this difference in treatment is justified? Why or why not?

5. Discuss the potential for adverse selection when insureds exercise the renewability or convertibility option in a term life insurance policy. Which is more likely to be affected by adverse selection?

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Black, Kenneth Black, Jr., Harold D. Skipper, and Kenneth Black III, Life and Health Insurance, 14th ed. Lucretian, LLC, 2013

Crawford, Muriel L. Life and Health Insurance Law, 8th ed. Homewood, Ill.: McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 1997.

Graves, Edward E., ed. McGill's Life Insurance, 8th ed. Bryn Mawr, Pa.: The American College, 2011.

Skipper, Harold D. and FSA Wayne Tonning The Advisor's Guide to Life Insurance, American Bar Association, 2013.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| American Council of Life Insurance | www.acli.com |

| Association for Advanced Life Underwriting | www.aalu.org |

| Life and Health Insurance Foundation for Education | www.lifehappens.org/Life |

| Life Office Management Association (LOMA) | www.loma.org |

| LIMRA | www.limra.com |

| NAIC InsureU | www.insureuonline.org |

| Society of Financial Services Professionals | www.financialpro.org |

| The American College | www.theamericancollege.edu |

![]()

1Although there is no legal limit, insurance companies often impose limits for underwriting reasons. Not only is the amount of insurance a company is willing to write on a life limited, but companies are reluctant to issue a policy with a beneficiary when no apparent insurable interest exists.

2This example is based on the 2001 CSO Composite Female Mortality Table, which was adopted by the NAIC in December 2002. According to the previous mortality table, the 1980 CSO Mortality Table, the mortality rate at age 21 was 1.07 per 1000 females.

3The $0.48 indicated in our simplified calculation reflects mortality only. In actual practice, life insurance rates include two additional factors: interest and loading. Life insurers specifically recognize the investment income that will be earned on premiums by assuming that premiums will be paid at the beginning of the year and that deaths will occur at the end of the year. The discounted value of future mortality costs is called the net premium. A loading for expenses is added to the net premium to derive the gross premium, which is the amount the buyer pays.

4The 2001 CSO Mortality Table assumes the last policyholders die before reaching age 121. Thus, a policy written under the 2001 CSO Table matures at age 121. If the insured has not died by this time, the insurance company will, in effect, declare him dead and pay the face value of the policy. The 1980 CSO Mortality Table had a maximum lifespan of 100 years, thus, earlier policies matured at age 100. Mortality tables are discussed in more detail in Chapter 13.

5An exception exists in the case of transfer for value. An example of a policy transferred for value would be if A purchases from B an existing policy for $10,000 on B's life, paying B$3000 for the policy. If B dies, A will be taxed on the $7000 gain. The taxation of policies transferred for value does not apply if the transferee is the person insured, a partner of the insured, or a corporation of which the insured is a director or stockholder.

6The net single premium is the insured's share of the discounted value of future claims. The net single premium is discussed in Chapter 13.

7To minimize the element of adverse selection, most companies impose a time limit within which the conversion must take place. In the 10-year term policy, the insured could be required to convert within 7 or 8 years after the date of issue of the original contract. If the policy is renewable, however, the only limitation is that conversion must take place before the limiting age for renewal or that it be converted within a certain period before the expiration of the last term for which it can be renewed.

8The variable annuity, which predated variable life insurance by over two decades, is discussed in Chapter 18. Briefly, however, it attempts to cope with the impact of inflation on retirement incomes by linking the accumulation of retirement funds to the performance of common stocks. The annuitant's premiums are used to purchase units in a fund of securities, much like an open-end investment company. These units are accumulated until retirement, and a retirement income is then paid to the annuitant based on the value of the units accumulated. The concept is based on the assumption that the value of a diversified portfolio of common stocks will change in the same directions as the price level.

9Variable life insurance has been available in the Netherlands since the mid-1950s, where it was originally introduced by a Dutch insurance company, DeWaerdye, Ltd. Under the Dutch version of variable life insurance, the face amount, the cash value, and the premiums are all variable, based on a fund invested in common stocks.

10The SEC granted an exemption from the provisions of the Investment Company Act of 1940 with respect to the separate funds in which the insurer invested the assets generated by variable life policies, but the policy itself must be registered under the Securities Act of 1933, and agents selling variable life must be registered as broker-dealers under the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934.

11A pure endowment is a contract that promises to pay the face amount of the policy only if the insured survives the endowment period. The benefits that each survivor receives are contributed to in part by the members of the group who do not survive to collect. If the purchaser of a pure endowment dies before the end of the period, there is no return. Pure endowment policies trace their roots to tontine policies, which provided payment to persons who survived until some deferred time, or until the other participants had died.

12Traditionally, individual life insurance comprises two subcategories: ordinary life insurance and industrial life insurance. Ordinary life insurance has a face amount of $1000 or more and premiums that are paid annually, semiannually, quarterly, or monthly. Industrial life insurance has a face amount of less than $1000 and premiums that are payable as frequently as weekly. The most distinctive feature of industrial life insurance is that the premiums are collected by a representative of the insurance company at the home of the insured. The weekly premium and its collection at the insured's home were important factors in keeping the policies in force, but this method of distribution and, hence, the policy are expensive. Industrial life insurance currently represents less than one tenth of 1 percent of all life insurance in force. Monthly Debit Ordinary (MDO) life insurance, also known as home service life insurance, is similar to industrial life insurance but with face amounts of $1000 or more. Like industrial life, premiums are collected at the insured's home, and expenses and premiums are relatively high. Because the volume of MDO life insurance is included in insurance company reports as ordinary life, there is no dependable data on the magnitude of this segment of the life insurance market.

* American Council of Life Insurers, 2012 Life Insurers Fact Book.

13For example, an employee in a 28 percent tax bracket would have to receive $277 in before-tax income to pay the equivalent of $200 in premiums contributed by the employer for group life insurance.

14The first NAIC model group law, adopted in 1917, set the minimum for groups at 50. Many states reduced this to 25, and the number has gradually dropped to 10.

15Credit life insurance is frequently sold in conjunction with a companion coverage: credit accident and health insurance. This insures against the disability of the borrower through accident or illness and provides benefits by meeting required payments for a specific loan during the debtor's disability. Benefits are commonly subject to some dollar maximum per payment and some maximum number of payments.

16As noted in Chapter 5, fraternals represent a special class of mutual insurers, usually associated with a lodge or fraternal order, that provide life insurance to their members. Most fraternals originally used the assessment principle, but the majority currently operate on a legal reserve basis.

17Servicemen's Group Life Insurance (SGLI) and Veterans Group Life Insurance (VGLI), which are sold by private insurers, are included in the private insurance industry totals in Table 12.2.