CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Identify and describe the major classes of benefits in the Old-Age, Survivors, Disability, and Health Insurance Program (OASDHI)

- Identify the persons who are eligible for benefits under the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program and how eligibility for benefits is derived

- Explain how benefits under the OASDI program are financed

- Explain how the amount of benefits received under OASDI is determined and the circumstances that can lead to a loss of benefits

- Evaluate the financial soundness of the Social Security system and identify the proposals that have been suggested to improve that soundness

- Explain the rationale for workers compensation laws and outline the principles on which the workers compensation system is based

- Describe the operation of the workers compensation system, including the types of injuries covered and the types of benefits

In Chapter 10, we noted how state unemployment insurance programs address the risk of income loss associated with unemployment. In this chapter, we turn to other social insurance programs that contribute to the security of the individual: the Social Security and workers compensation systems. We study these social insurance programs to acquire tools that may be used in dealing with the risks to income facing the individual. Our examination will allow us to relate the benefits under these programs to the overall risk management problem facing the individual.

![]()

OLD-AGE, SURVIVORS, DISABILITY, AND HEALTH INSURANCE

![]()

The Old-Age, Survivors, Disability, and Health Insurance Program (commonly known as Social Security) protects eligible workers and their dependents against the financial losses associated with death, disability, superannuation, and sickness in old age. The benefits available under the program to the dependents of a deceased worker or to a disabled worker and his or her dependents are an important part of an individual's income protection program. The retirement benefits are a fundamental element in the individual's retirement program. Any attempt to fit insurance to the needs of the family must consider the benefits available under OASDHI. There are four classes of benefits:

- Old-age benefits The old-age part of OASDHI provides a lifetime pension beginning at an individual's full retirement age (or a reduced benefit as early as age 62) to each eligible worker and certain eligible dependents. The amount of this pension is based on the worker's average earnings during some period in the working years. The full retirement age depends on the worker's year of birth and ranges from 65 to 67.

- Survivors' benefits Although the Social Security Act originally provided only retirement benefits, complaints that the system was unfair to workers who died before retirement (or after retirement) induced Congress to expand the program, extending benefits to the dependents of a deceased worker or retiree. The survivors' portion of the program provides covered workers with a form of life insurance, the proceeds of which are payable to their dependent children and, under some conditions, surviving spouses.

- Disability benefits Disability benefits were added to the program in 1956, when such benefits were extended to insured workers who became disabled between the ages of 50 and 64. In 1960, this coverage was broadened to all workers who met certain eligibility requirements. A qualified worker who becomes totally and permanently disabled is treated as if he or she had reached retirement age, and the worker and dependents become eligible for the benefits that would otherwise be payable at full retirement age.

- Medicare benefits The Medicare portion of the system was added in 1965. It offers people over 65 and certain disabled persons protection against the high cost of hospitalization, skilled nursing, hospice care, home health services, and other kinds of medical care. In addition, it provides an option by which those eligible for the basic benefits under the medical program may purchase subsidized medical insurance to help pay for doctors' services and other expenses not covered by the basic plan.1

All income benefits are subject to automatic adjustments for increases in the cost of living. Benefits for all recipients are increased automatically each January if the Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows a rise in the cost of living during the preceding year. Congress retains the right to legislate increases in benefit levels, and there is no automatic increase in any year for which Congress has legislated an increase.

![]()

Eligibility and Qualification Requirements

Initially, the act covered only about 60 percent of the civilian workforce. The major classes not included were the self-employed, agricultural workers, government employees, and employees of nonprofit organizations. Coverage was gradually expanded until nearly all private employment and self-employment qualify for OASDHI. Today, more than 95 percent of the labor force is covered, most on a compulsory basis. Most of those not covered are state, local, or federal employees.2

To qualify for benefits, an individual must have credit for a certain amount of work under Social Security. Insured status is measured by quarters of coverage, and individuals earn these quarters by paying taxes on their wages. Some benefits are payable only if the worker has enough quarters of coverage to be considered fully insured, whereas other benefits are payable if the worker is merely currently insured.

Quarter of Coverage For most employment before 1978, an individual earned one quarter of coverage for each calendar quarter in which he or she paid the Federal Insurance Contribution Act (FICA) tax on $50 or more in wages. (A calendar quarter is any three-month period beginning January 1, April 1, July 1, or October 1.) Since 1978, the level of earnings on which FICA taxes must be paid for a quarter of coverage is adjusted annually, based on increases in average total wages for all workers. By 2013, one quarter of coverage was granted for each $1160 of earnings, up to a maximum of four quarters per year. Further increases will take place as the average total wages for all workers increase.

Fully Insured Status Fully insured status is required for retirement benefits. To be fully insured, the worker must have one quarter of coverage for each year starting with the year in which he or she reaches age 22, up to, but not including, the year in which the worker reaches age 62, becomes disabled, or dies. For most people, this means 40 quarters of coverage. No worker can achieve fully insured status with fewer than 6 quarters of covered employment, and no worker needs more than 40 quarters. Once a worker has 40 quarters of coverage, he or she is fully insured permanently.

Currently Insured Status To be currently insured, a worker needs 6 quarters of coverage during the 13-quarter period ending with the quarter of death, entitlement to retirement benefits, or disability. Basically, currently insured status entitles children of a deceased worker (and the children's mother or father) to survivor's benefits and provides a lump-sum benefit in the event of the worker's death.

![]()

Financing

The OASDHI program is administered by the Social Security Administration.3 It is financed through a system of payroll and self-employment taxes levied on all persons in the program. For wage earners, a tax is paid on wages up to a specified maximum by employers and employees. In the original act of 1935, a tax rate of 1 percent applied to the first $3000 of an employee's wages, and the employer and employee were each liable for the tax up to a $30 annual maximum each. When the Medicare program was added in 1965, a separate Hospital Insurance (HI) tax was added, which was combined with the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability tax to make up the total FICA tax. The tax rate and taxable wage base to which it applies have increased over time as the program has expanded. In 2013, the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability tax was 6.2 percent and the Medicare tax was 1.45 percent, making a combined rate of 7.65 percent, payable by the employee and matched by the employer.

The Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability tax applies to a taxable wage base that automatically increases in the year following an automatic benefit increase. Like the automatic increases in benefit levels, congressional changes in the taxable wage base override the automatic adjustment provisions. Automatic increases in the earnings base are geared to the increase in average wages for all workers. With the legislated changes and automatic adjustments, the taxable wage base had increased to $113,700 by 2013 and will continue to increase in the future. Historically, the Medicare tax applied only up to the maximum taxable wage base. The 1993 Tax Reform Act eliminated the maximum wage base for the Medicare tax, and the tax now applies to total earned income without limit.

Self-employed persons pay a tax rate that is equal to the combined employer-employee contribution (i.e., 15.3 percent in 2013). Self-employed persons are allowed a deduction against income taxes equal to half the self-employment taxes paid for the year.

In addition to the basic OASDI and Medicare taxes that apply to everyone, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2009 (“Obamacare”), created two new taxes, targeted at high income individuals, that become effective in 2013. The Unearned Income Medicare Contribution Tax is a new tax on investment income. Specifically, the tax is 3.8 percent of the lower of (1) net investment income for the year and (2) modified adjustable gross income (AGI) over a threshold amount. The threshold amount is $250,000 of modified AGI for married individuals filing jointly, $200,000 for single individuals, and $125,000 for a married individual filing separately, and these thresholds are not indexed. Certain sources of income are exempt from the tax, including tax-exempt municipal bond interest, nontaxable veteran's benefits, and distributions from qualified retirement plans.

The Additional Medicare Tax is .9% of wages, compensation, and self-employment income above a threshold. The threshold is $250,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly, $125,000 for a married tax-payer filing separately, and $200,000 for a single taxpayer. There is no employer match on the these taxes, and the thresholds are not indexed.

Some costs are financed from general funds of the U.S. Treasury. Among these are certain costs under the Medicare program and cash payments to some uninsured persons over age 72.

![]()

Amount of Benefits

Most OASDHI benefits are based on a benefit called the primary insurance amount (PIA). The PIA is the amount of the retirement benefit payable to a worker who retires at normal retirement age (which is between 65 and 67, depending on the year of birth). It is computed from the individual's average indexed monthly earnings (AIME), which is the worker's average monthly wages or other earnings during his or her computation years, indexed to current wage levels. All monthly income benefits under OASDI to the worker and his or her eligible dependents are based on the PIA.

Computing the Primary Insurance Amount The first step in computing the primary insurance amount is to determine the average indexed monthly earnings. This is the average monthly earnings on which the worker paid FICA taxes, indexed to current wage levels. It is calculated by indexing prior earnings, dropping some low years, and calculating the average.

Indexing Earnings A worker's past earnings are indexed to wage levels in effect in the second year prior to eligibility, by comparing average wages covered by Social Security over the years. For example, consider an individual who reached age 60 in 2011 and was applying for benefits in 2013. Since individuals are first eligible for retirement benefits at age 62, prior earnings would be indexed to the year in which the person reached age 60, or 2011. Average earnings in 2011 ($42,979.61) were 4.9797 times average earnings in 1975, so wages earned in 1975 would be indexed by multiplying the worker's FICA-taxed wages in 1975 by 4.9797. Other years' wages would be similarly adjusted. Earnings after the index year are not adjusted.

Dropping Low Years After indexing prior earnings, the individual may be permitted to drop some low years of earnings. The number of years that must be included when computing the average depends on the age of the individual and the type of benefits for which he or she is applying.4 An individual who works longer than the required number of years may be able to exclude some additional years of low earnings. On the other hand, if the individual was not employed at least the required number of years, some years of zero earnings must be included when calculating the average.

Computing the Primary Insurance Amount After dropping the allowed number of years of low earnings, total indexed earnings are divided by the number of months included to produce the AIME. The AIME is converted to the PIA using a formula prescribed by law. The formula used in converting the AIME to the PIA provides for a higher percentage of the average indexed earnings at lower income levels than at higher income levels.5 For a worker with low earnings (45 percent of average wages during working years), the PIA is about 50 percent of preretirement earnings, but workers with high earnings (160 percent of average wages) receive about 30 percent of preretirement earnings.

![]()

Classes of Benefits

Retirement Benefits Workers who are fully insured are entitled to receive a monthly pension for the rest of their lives. If the worker retires at full retirement age, the benefit is equal to 100 percent of his or her PIA. Workers may elect to receive benefits as early as age 62, but the benefit is reduced 5/9 of 1 percent for each month prior to full retirement age that benefits commence (a 20 percent or greater reduction at age 62). The age at which full retirement benefits are payable was originally age 65, but in the year 2000, it began increasing in gradual steps to age 67. Workers who delay retirement receive an increase in their PIA for each month between full retirement age and 72 that they delay retirement. This credit varies, depending on the date of birth. It increased according to a legislated schedule until it reached 2/3 percent per month in 2008.

In addition to the benefits received by the worker at retirement, others may receive benefits if the worker was fully insured. Total benefits received by the family, however, are subject to an overall maximum family benefit.

Spouse's Benefit The spouse of the retired worker (or a spouse divorced after 10 years of marriage) is entitled to a retirement benefit at full retirement age equal to 50 percent of the worker's PIA. Like the retired worker, the spouse may choose a permanently reduced benefit as early as age 62. The benefit to the spouse of a retired worker is reduced 25/36 percent for each month prior to full retirement age.6

Children's Benefit The benefit for children of a retired worker is payable to three classes of dependent children: (1) unmarried children under age 18; (2) unmarried children age 18 or over who are disabled, provided they were disabled before reaching age 22; and (3) unmarried children under age 19 who are full-time students in an elementary or secondary school. The benefit to each eligible child of a retired worker is 50 percent of the worker's.

Mother's or Father's Benefit A retired worker's spouse who has not yet reached age 62 may still be entitled to a benefit if he or she has care of a child who is receiving a benefit. A mother's benefit is payable to the wife of a retired worker and a father's benefit is payable to the husband of a retired worker if either has care of child under 16 or a disabled child who is receiving a benefit.7 This benefit is 50 percent of the worker's PIA.

Family Maximum All income benefits payable to a worker and his or her dependents are subject to a family maximum. The family maximum is based on a formula applied to the PIA.8 If total family benefits are greater than the family maximum, each individual's benefit, except the retired worker's, is reduced.

Survivors' Benefits Benefits are payable to certain dependents of a deceased worker, provided that the worker had insured status, which varies for the different classes of survivors' benefits. Once again, total benefits are subject to an overall maximum family benefit. The benefits payable under this part of the program include the following:

Lump-Sum Death Benefit A $255 lump-sum death benefit is payable to the surviving spouse or children of the deceased worker.

Children's Benefit The children's benefit is payable to dependent children of a deceased worker in any of the three classes noted earlier. The benefit to each eligible child of a deceased worker is 75 percent of the worker's PIA.

Mother's or Father's Benefit A mother's or father's benefit is payable to the widow or widower of a deceased worker who has care of a child under 16 (or a disabled child over 16) who is receiving benefits. This benefit is 75 percent of the worker's PIA.

Widow's or Widower's Benefit The widow or widower of a deceased worker (or a worker's divorced wife of 10 years of marriage) is entitled to a retirement benefit at age 65 equal to 100 percent of the worker's PIA. The widow or widower may elect to receive a permanently reduced benefit as early as age 60. The widow's or widower's benefit is also payable to the spouse of a deceased worker who becomes disabled after age 50 and not more than 7 years after the death of the worker or the end of his or her entitlement to a mother's or father's benefit. A disabled widow or widower age 50 to 59 who is entitled to a benefit receives 71.5 percent of the PIA.9

Parents' Benefit The parents' benefit is payable to a deceased worker's parents who are over age 62 if they were dependent on the worker for support at the time of death. One parent is entitled to a retirement benefit at age 62 equal to 82½ percent of the worker's PIA. The maximum benefit for two dependent parents is 150 percent of the worker's PIA (75 percent each).

Required Insured Status Under the survivors' benefit program, the children's benefit, mother's or father's benefit, and lump-sum death benefit are paid if the worker is fully or currently insured. All other benefits are payable only if the worker was fully insured.

Disability Benefits Disability benefits are payable to a worker and eligible dependents when a worker who meets special eligibility requirements is disabled within the meaning of that term under the law. Disability is defined as a “mental or physical impairment that prevents the worker from engaging in any substantial gainful employment.” The disability must have lasted for 6 months and must be expected to last for at least 12 months or be expected to result in the prior death of the worker. Persons who apply for Social Security benefits are referred to the state agencies called disability determination services (DDSs) to evaluate the disability. If the state agency is satisfied that the worker is disabled as defined by the Social Security Act, the individual is certified as such and benefits are paid. However, benefits do not start until the worker has been disabled for five full calendar months.

Qualification requirements for disability benefits depend on the worker's age. Workers who become disabled before reaching age 24 qualify if they have 6 quarters out of the 12 quarters ending when the disability began. Workers who became disabled between ages 24 and 31 must have 1 quarter of coverage for each 2 quarters beginning at age 21 and ending with the onset of disability. Workers over age 31 must be fully insured, and must have 20 out of the last 40 quarters in covered employment.

In general, disability benefits are payable to the same categories of persons and in the same amounts as retirement benefits but are subject to a special family maximum benefit. Total monthly payments for a disabled worker with one or more dependents are limited to the lower of 85 percent of the worker's AIME or 150 percent of the worker's disability benefit (but not less than 100 percent of the worker's PIA).10

The disability insurance program has a number of provisions designed to encourage beneficiaries to return to gainful employment. Beneficiaries may be referred to state vocational rehabilitation agencies for assistance. They are permitted to return to employment for a “trial work period” without adversely affecting their benefits. Any month in which the beneficiary earned more than $750 (for 2013) is counted as part of the trial work period. The individual does not lose disability benefits until he or she has had nine such months during a rolling 60-month period.

![]()

Summary of Qualification Requirements

Although the preceding discussion may seem complicated, the nature of the qualification requirements can be summarized concisely, and although all qualifications are important, some seem more so than others. The survivors' benefits payable to children and mother's or father's benefits require only that the worker have been fully or currently insured. To be eligible for any retirement benefits, the worker must have been fully insured. Table 11.1 summarizes the qualification requirements for the various categories of benefits under OASDHI.

![]()

Loss of Benefits—the OASDHI Program

A person receiving benefits may lose eligibility for benefits in several ways. The most common causes of disqualification under the law are the following:11

TABLE 11.1 Insured Status Required for OASDHI Benefits

| Benefit | Insured Status Required of Workers |

| Survivors' Benefits | |

| Children's benefit | Fully or currently insured |

| Mother's or father's benefit | Fully or currently insured |

| Dependent parent's benefit | Fully insured |

| Widow or widower age 60 or over | Fully insured |

| Lump-sum death benefit | Fully or currently insured |

| Retirement Benefits | |

| Retired worker | Fully insured Spouse of retired worker |

| Fully insured Child of retired worker | Fully insured Mother's or father's benefit |

| Fully insured | |

| Disability Benefits | |

| Disabled worker | Twenty of last 40 quarters fully insured or |

| Dependent of disabled worker | Six of last 12 quarters if under age 24 |

| One of every 2 quarters since age 21 if between 23 and 31 | |

| Medicare Benefits | Entitlement to cash benefits under Social Security or Railroad Retirement, or have reached age 65 before 1968, or meet special eligibility requirement |

- Divorce from a person receiving benefits For example, a retired worker's wife or husband who is receiving a benefit based on the qualification of that worker loses the right to the benefit after divorce unless he or she was married to the worker for 10 years or longer.

- Attainment of age 18 by a child receiving benefits The benefit payable to the child of a deceased, retired, or disabled worker stops when the child reaches age 18 unless the child is in high school, in which case the benefit is payable until age 19. When the child reaches age 16, the mother's or father's benefit stops even though the child continues to receive a benefit. The child-raising widow or widower of a deceased worker, therefore, faces a period during which no benefits are payable. Between the time the youngest child turns 16 and the time the widow or widower reaches age 60, no benefits are payable. This period is commonly referred to as the blackout period.

- Marriage The rules governing the loss of benefits through marriage or remarriage are complicated. As a rule, if a person receiving a monthly benefit as a dependent or survivor marries someone who is not a beneficiary, his or her payment stops. On the other hand, when both parties are beneficiaries, payments may continue. For example, a widow receiving mother's benefits (because of a child under 16) will keep her benefits if she marries an individual receiving retirement or disability benefits. There are a number of exceptions to these rules.12 Interested persons should contact their local Social Security office for a determination in specific situations.

- Adoption If a child receiving a benefit is adopted by anyone except a stepparent, grandparent, aunt, or uncle, the payment to the child stops.

- Disqualifying income Sometimes, persons receiving Social Security benefits continue to work. Some work full-time, others only part-time. The same is true with respect to dependents receiving benefits. The Social Security laws provide that if a person receiving benefits earns additional income, he or she may lose a part or all of his or her benefits, depending on the amount earned. Certain amounts of earnings are permitted, but earnings in excess of these amounts reduce the Social Security benefit.

Disqualifying Income For 65 years, from its inception in 1935 until 2000, the Social Security System enforced an “earnings test,” under which benefits payable to beneficiaries could be reduced if the beneficiary had earned income. In 2000, faced with what most people agreed was a growing crisis in the system, Congress decided to eliminate the Social Security earnings test for persons over the normal retirement age. This means that a worker can continue to work full-time and draw his or her full Social Retirement benefit.

For beneficiaries under their normal retirement age, the earnings test remains, and Social Security benefits are reduced if the individual's earned income exceeds exempt amounts. The annual exempt amount of earnings increases each year, based on increases in national earnings. In 2013, the exempt earnings amount for persons under the normal retirement age was $14,640. For earnings in excess of the exempt amount, $1 in benefits will be withheld for each $2 in earnings in excess of the exempt amount.

Because some earnings can reduce Social Security benefits, it is important to distinguish those types of income that do not affect Social Security benefits. Among the items that do not count as disqualifying income are (1) pensions and retirement pay, (2) insurance annuities, (3) dividends from stock (unless the person is a dealer in stock), (4) interest on savings, (5) gifts or inheritances of money or property, (6) gain from the sale of capital assets, and (7) rental income (unless the person is a real estate dealer or participating farm landlord).

Taxation of Benefits Social Security benefits were originally exempt from taxes. Beginning in 1984, however, beneficiaries who have significant income in addition to the Social Security benefits must pay taxes on a portion of their Social Security benefits. The amount of the benefits subject to tax depends on the combined income and the filing status of the individuals. Combined income is the sum of adjusted gross income (AGI), tax-exempt interest, and half of the Social Security benefits. If combined income for an individual is between $25,000 and $34,000 or if income for a couple filing jointly is from $32,000 to $44,000, 50 percent of the Social Security benefit may be taxed. For combined income above $34,000 for a single individual or $44,000 for a couple filing jointly, up to 85 percent of benefits may be taxed.

Because the provisions relating to taxation of Social Security benefits in the second tier were enacted later and are superimposed on the first tier, the system will become clearer if we discuss the two tiers in the sequence in which they became effective.

For the first tier, the amount of benefits subject to tax is the smaller of (1) half the Social Security benefits or (2) half of the amount by which modified AGI (adjusted gross income plus tax-exempt interest) plus half of the Social Security benefits exceed the so-called base amounts, namely $25,000 for single taxpayers and $32,000 for married taxpayers filing jointly.13

Because the formula for the first tier is confusing, let us consider an example. Abner, Baker, and Cole are all single taxpayers, and each receives $18,000 in Social Security benefits. Abner has $10,000 in earned (taxable) income, Baker has $15,000 in earned income, and Cole has $30,000 in taxable income. In addition, each has $5,000 in tax-exempt interest. The determination of the portion of Social Security benefits that must be included as taxable income is made as follows:

As this chart shows, none of Abner's Social Security benefits will be included in taxable income. His combined income plus half of his Social Security benefit is less than the $25,000 base amount; since this is less than half of the Social Security benefit, none of his benefits is taxable. Baker's combined income plus half of his Social Security benefits exceeds the base amount by $4000; half of this $4000 is smaller than half of the Social Security benefits, so $2000 is includable in taxable income. Finally, Cole's combined income plus half of his Social Security benefits exceeds the $25,000 base amount by $19,000. Since half of the $19,000 is greater than half of his Social Security benefits, he will be taxed on half of the Social Security benefits.

Perhaps because the rules were not sufficiently complex, Congress added the second tax tier for tax years beginning in 1994. Under the new rules, persons whose modified AGI plus half the Social Security benefit exceeds $34,000 ($44,000 on a joint return) will be taxed on up to 85 percent of their Social Security benefit. These taxpayers must include in gross income the lesser of the following:

- 85 percent of the total benefits received, or

- 85 percent of the amount by which AGI plus half of the Social Security benefits exceeds the $34,000 or $44,000 threshold, plus the smaller of (1) the amount that would have been included under pre-1993 law or (2) $6000 on a joint return ($4500 on a single return).

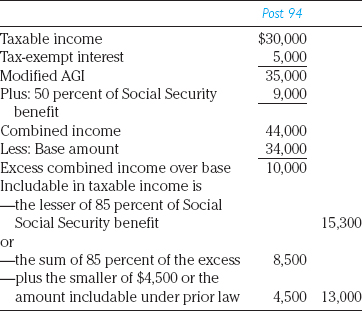

Cole, who would have been required to include $9000 in Social Security benefits under prior law, is subject to the new threshold. Using the $34,000 threshold effective since 1994, determination of the benefits includable in Cole's taxable income is the following:

To compute the taxable income for persons whose combined income exceeds the higher thresholds, the amount that would have been includable under prior law must first be computed. The amount that is included is then the lesser of 85 percent of the Social Security benefit ($15,300) or 85 percent of the combined income in excess of the threshold ($8500) plus the smaller of $4500 or the amount that would have been includable under the previous rules ($9000). Since $8500 plus $4500 ($13,000) is less than $15,300, $13,000 will be includable in taxable income.

Social Security recipients fall into three classes with respect to taxation of benefits: (1) persons whose Social Security benefits are not taxed; (2) persons who must include up to 50 percent of their Social Security benefits in taxable income; and (3) persons who must include up to 85 percent of their Social Security benefit in their taxable income. Revenues from the increased taxation of Social Security benefits are transferred to the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund.

![]()

Soundness of the Program

One of the central issues in the debate over passage of the Social Security Act was the system's financing. Many authorities proposed that the federal government support the program out of general revenues; others maintained that it should be financed completely by the contributions of the workers and their employers. The decision was reached that only revenues provided by Social Security taxes would be used to pay benefits. The intent at that time (and the principle that has, for the most part, been carried down to the present) was that the system should be self-supporting from contributions of covered workers and their employers. The bases for this decision were complex, but one of the primary reasons was to give the participants a legal and moral right to the benefits.14

Once the issue of a self-supporting program was settled, there was disagreement over whether to fund the program with a reserve similar to those used in private insurance or whether to operate it on a pay-as-you-go basis. The proponents of a pay-as-you-go approach prevailed, creating the system in use.

Pay-as-You-Go System Under the pay-as-you-go system, those who are eligible receive benefits out of Social Security taxes paid by those who are working. In turn, today's workers will receive benefits after retirement from funds paid by the labor force at that time. The money collected is allocated to trust funds, from which the benefits are paid. There are separate trust funds for the Old-Age and Survivors program, the Disability program, the Hospital Insurance program of Medicare, and the Supplementary Medical Insurance program. The trust funds were conceived as a contingency reserve to cover periodic fluctuations in income but not to fund liabilities to future recipients.

The rationale for the pay-as-you-go system seems logical. Given a stable system with a high ratio of taxpayers to beneficiaries, modest tax rates can support relatively generous benefits. When current workers retire, their retirement benefits will be funded by a new generation of taxpayers (and a larger one if there is population growth). Moreover, those taxpayers will make contributions based on higher earnings as a result of improved national productivity. In theory, this results in an increasing level of benefits.

Difficulties arise, however, when the relationship between the number of beneficiaries and the number of taxpayers changes adversely. If fewer taxpayers can support the benefits, tax rates must rise. That is, in fact, what has happened.

The combined Social Security contribution for employers and employees climbed from a modest $348 in 1965 to $17,396 for workers earning $113,700 in 2013, with further increases likely in the future. For the average wage earner, the greatest increase in the cost of living over the past 25 years has been the hike in Social Security taxes.

The increasing tax for workers covered under the program and the predicted financial difficulties stem from two causes: the increasing number of beneficiaries under the program and the increasing level of benefits. In 1947, when only retired persons and survivors were eligible for benefits, about 1 out of every 70 Americans received Social Security checks. With the expansion of the program to include disabled workers and their dependents, coupled with the changing age structure of the population, the ratio of beneficiaries to taxpayers had increased to about 1 to 3.3 by 1998. As the large cohort of post-World War II baby boomers reaches age 65, the ratio will become even worse. In 2035, it is projected that there will be 2 taxpayers for each beneficiary with a continued gradual decrease after that due to increasing longevity.

The growth in the number of recipients and increasing benefit levels caused the system to reach a critical point in the late 1970s. In December 1977, Congress enacted a Social Security bailout plan to save the system from impending bankruptcy. It included the largest peacetime tax increase in the history of the United States up to that time. In signing the 1977 amendments, President Jimmy Carter stated, “Now this legislation will guarantee that from 1980 to the year 2030, the Social Security funds will be sound.” Unfortunately, the measures designed to save the system did not contain a sufficient margin of safety. As a result, the salvation was short-lived and another financing crisis occurred in 1981–1983. By 1981, the system's board of trustees warned in its annual report to Congress that, even under the most optimistic assumptions, the OASDI trust fund would be bankrupt by the end of 1982. In 1982, the Old-Age and Survivors Trust Fund was forced to borrow from the Disability and Hospital Insurance trust funds to meet benefits obligations. Recognizing that corrective action was imperative, President Reagan appointed the bipartisan National Commission on Social Security Reform in December 1981 to review the system's financing problems and to recommend a solution. In mid-1983, Congress enacted legislation embodying the commission's proposals. The 1983 legislation included massive tax increases in 1988 and 1990, a gradual increase in the normal retirement age beginning in the year 2000, and taxation of Social Security benefits for persons with incomes above a certain level.

In an effort to avoid a repetition that occurred as a result of faulty assumptions in the 1977 legislation, the changes enacted in 1983 were made on the basis of ultraconservative estimates. Recognizing the need to plan for the large numbers of individuals retiring in the next century, Congress enacted changes that would result in surpluses for a period of time, that is, revenues exceeding disbursements. Because the economy performed better than had been anticipated, the Social Security trust funds increased from modest contingency funds totaling about $45 billion in 1982 to more than $2 trillion in 2007. According to the 2013 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the OASDI Trust Funds, combined assets of the Old Age Survivor Insurance Fund and Disability Income Fund are projected to increase over the next several years, from $2.678 billion at the beginning of 2012 to $3.06 billion at the beginning of 2021. Beginning in 2021, however, assets will begin to decline, as benefits exceed taxes and interest. Under intermediate assumptions, trust fund assets are projected to be exhausted in 2033.15

A further complication is that the assets of the trust funds are invested only in federal government securities, a special class of securities that are only available to the Social Security program. In effect, this means the federal government is borrowing from the program. The securities are backed by the full faith and credit of the federal government, and as the trust funds decrease, the federal government will have to redeem the bonds. Some experts point to the challenge of doing so, particularly with the concerning federal debt and deficit positions. Thus, there continues to be a basis for concern about the long-run soundness of the program. The fundamental imbalance between workers and recipients will continue to grow, increasing the difficulty of funding benefits to future recipients.

Proposals for Change In the face of these prospective difficulties, a number of changes in the system have been proposed. Some suggest a revision in the financing of the system; others call for a reevaluation of benefit levels.

Proposals for Changes in Financing The proposals for changes in financing the system have been many and varied. One approach suggests that the increased costs of the system be financed through higher taxes rather than through raising the earnings base. Proponents of this position argue that benefit increases should not be financed by the “painless” process of increasing the tax base. Higher tax rates would require all covered workers to share in the increased cost, thereby making the desirability of the increased benefits an issue to be considered by all.

Other proposals for changes in the system's funding take a directly opposite position, maintaining the system is highly regressive (most burdensome on low-income groups) and the tax base should be eliminated completely, with Social Security taxes applying to all income earned. Others of this school have suggested the system should be financed out of general revenues rather than through a separate tax.

Proposals for Changes in Benefit Levels The Social Security system was originally developed on the principle that the amount of the social insurance benefit should be sufficient to provide a floor of protection, meaning an amount sufficient to maintain a minimum standard of living. This floor of protection was then to be supplemented by the individual through private insurance or other devices. Some critics believe the system provides benefits to recipients in excess of this floor of protection level. They have suggested that the level of benefits be limited.

A second proposal for changing the benefits structure focuses on the age for receiving full retirement benefits. When the Social Security Act was passed in 1935, the normal retirement age for benefits was 65. The 1983 amendments instituted a gradual increase in this age to 67 years by the year 2022. Some critics argue this compromise did not go far enough and there should be a significant and faster increase in the normal retirement age. They base this argument on the dramatic improvements in life expectancy since 1935, resulting in a longer period of retirement for current retirees.16

A third proposal focuses on changes in the way benefit increases are determined. Currently, benefits increase annually by the increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Economists argue that the CPI overstates the effect of price increases on consumers because the measure ignores how people adjust their buying patterns to a change in relative prices. For example, if beef prices increase while chicken does not, consumers might consume more chicken. Failing to account for these substitution effects is known as substitution bias. In response to the problem, the U.S. Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics developed an alternative measure, known as the Chained-CPI, which produces slightly lower measures of inflation. A number of policymakers have recommended using the Chained-CPI for determining Social Security cost-of-living adjustments (COLA), which would result in a reduction in COLAs of approximately .25 percent annually. In March 2013, the Congressional Budget Office estimated such a change would cut Social Security benefits by a total of $127.2 billion between 2014 and 2023.

Privatizing Social Security The most dramatic proposal for addressing the financial problems affecting Social Security is that it be privatized, with a change from the current pay-as-you-go system to a program with advance funding, in which contributions by workers and their employers are invested in the private sector. At one time, this would have been unthinkable. As long as Social Security was a “good deal” for participants and provided benefits that were substantially greater than the contributions they had made, a fundamental reform such as privatization was politically impossible. The current crisis in the system and the increasing imbalance between participant contributions and benefits has opened consideration to a variety of alternatives, including privatization, an idea that some scholars support.

One of America's most respected economists, Professor Martin Feldstein of Harvard University, has argued in favor of privatization.17 The problem, according to Professor Feldstein, is the pay-as-you-go system we use to finance the Social Security system. With benefits financed by current tax revenues, the 600 percent increase in the tax rate and the growth in the labor force since the Social Security Act was adopted has permitted the Social Security System to pay retirees more in benefits than those retirees paid in taxes during their working years. For current workers, and for those who will be entering the labor force, Social Security tax rates will have to increase to balance the aging of the population and the increasing number of retirees relative to those who are working. This means that the rate of return that future workers will receive on their contributions is limited to the rate at which Social Security tax revenues will increase. This, it appears, will be limited to the increases, which in turn depends on the growth in incomes and population. According to Feldstein, the implicit rate of return that is achievable from these sources is a modest 2.5 percent.

If the problem is a low rate of return, Feldstein argues, why not invest Social Security revenues where the return will be greater? Historically, over the past 30 years, funds that have been invested in stocks and bonds have earned a higher return than the U.S. government assets in which the funds are invested. Shifting contributions from the current unfunded system to a funded program with Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) or 401(k) plans would permit employees to earn that higher rate of return. Professor Feldstein estimated that if contributions were invested in a funded account earning a real return of 9 percent, the cost of financing Social Security benefits would be cut by about 80 percent.

Many other nations have done what Professor Feldstein has recommended, shifting from unfunded pay-as-you-go systems to funded privatized systems. Although the approach adopted by other countries differs in detail, the common thread is requiring that employer and employee contributions be invested in mutual funds or similar private assets.

The difficulty, of course, is that a privatized system cannot be achieved immediately. There would be a transition period, and the Social Security Administration would have to continue to pay benefits to existing retirees while new funds were accumulated and invested through the individual accounts. Critics also argue that total administrative costs will increase and many workers are not competent to make their own investment decisions.

Report of the Advisory Council on Social Security In January 1997, a special Advisory Council on Social Security appointed in 1994 to examine the long-term financing of Social Security issued its report. The council concluded that the program faces “serious problems in the long run,” requiring attention in the near term. These problems, according to the council, were the funding deficit in the immediate future and beyond, the issue of equity from one generation to another, and the increasing skepticism among younger workers about the future of the system.18

All council members agreed the current pay-as-you-go system should be changed and recommended there be partial advance funding for Social Security. Despite agreement about the problems facing the system, the council could not agree on a single proposal to address the system's financial costs will be higher with a privatized system and that problems.

Bush Commission to Strengthen Social Security During the 2000 election campaign, candidate George W. Bush argued strongly for a program of partial privatization, a plan labeled by his Democratic opponent as a risky scheme. In January 2001, almost immediately upon taking office, President George W. Bush appointed a new President's Commission to Strengthen Social Security to consider the future of Social Security.

After eleven months of public hearings and debate, the commission issued its final report in December 2001.19 The commission developed three separate models for consideration, all of which provide for voluntary private investment accounts. The report met with immediate disapproval from the opponents of privatization.

Beyond proposing private accounts, the Bush Commission concluded that Social Security cannot be rescued from the impending financial problems without cutting benefits for retirees and disabled Americans, using money from elsewhere in the federal budget, or both. In the commission's view, whether additional funds are committed to the system or benefit levels are brought to a level that can be sustained within current projected revenues, private accounts will enhance retirement security.

The issue of privatization remains highly contentious. Unquestionably, it involves the largest structural change in the program since its inception in 1935. While it is clear that changes must eventually be made to the OASDI program to address its fiscal problems, whether private accounts will be part of the solution remains unclear.

There is widespread recognition that the Social Security system's funding problems require a solution, yet no solution is in sight. The Social Security Commission reported in 2001, pointing to the looming crisis, but twelve years later, no action had been taken. This will likely remain a haunting problem for our society, solved only when it becomes an immediate crisis.

![]()

WORKERS COMPENSATION

![]()

Workers compensation is a social insurance program that provides covered workers with protection against work-related disability and death. Workers compensation provides benefits for the cost of medical care and income to workers and their dependents when a worker is disabled or killed as a result of a work-related injury or occupational disease. The workers compensation system is based on statutes that exist in all states that require covered employers to provide benefits specified by the law to covered workers and their dependents.

![]()

Historical Background

The workers compensation laws were enacted in response to a growing dissatisfaction with the system then in use for compensating injured employees and their dependents. Under English common law, which had developed in a society dominated by handicraft industries, certain legal principles evolved that made it difficult if not impossible for an injured worker to collect indemnity for an industrial injury. These doctrines were embodied in the special branch of law that had developed to deal with injuries to workers, called employers liability law. Under employers liability law, a worker who was injured on the job could collect for the injury only if he or she could prove the injury resulted from the employer's negligence. To establish fault, the employee had to prove that the employer had violated one of five common-law obligations: (1) to provide the employee with a safe place to work; (2) to provide safe tools and equipment; (3) to provide sane and sober fellow employees; (4) to set up safety rules and enforce them; and (5) to warn of any dangers in the work that the worker could not be expected to know about.

Although these common-law obligations established a basis for recovery of damages, the employer could interpose three common-law defenses that were often sufficient to defeat the worker's claim. The first was contributory negligence. Under this doctrine, if the employee's own negligence contributed to the accident in the slightest degree, he or she lost all right to collect damages. The second defense was the fellow servant rule, which held that the employer was not liable when the worker was injured by a fellow employee. Finally, the assumption-of-risk doctrine held that an employee was presumed to accept the normal risks associated with the job. If a worker continued employment while knowing, or when he or she might have been expected to discover, that the premises, tools, or fellow employees were unsafe, he or she was deemed to have assumed the risks connected with the unsafe conditions.

Although the severity of the common-law defenses was softened, the modifications did not solve the fundamental problems inherent in a system based on the principle of negligence.20 To establish negligence, litigation was necessary, and in most cases, the worker did not have the resources to bring suit. Even if the worker won the suit, a substantial portion of the judgment went to the attorney who had accepted the case on a contingency basis. The size of the attorney's fee commonly represented 50 percent of the amount of the judgment. Finally, there were some cases in which workers were injured where there was no employer negligence. Although the injured worker could find no one to sue, the financial loss in such instances was just as severe as when the employer was at fault. The unsatisfactory status of the worker under common law, and the social and economic consequences of industrial injuries led to a new way of distributing the financial costs of industrial accidents.

![]()

Rationale of Workers Compensation Laws

The workers compensation principle is based on the notion that industrial accidents are inevitable in an industrialized society. Because the entire society gains from industrialization, it should bear the burden of these costs. workers compensation laws are designed to make the cost of industrial accidents a part of the cost of production by imposing absolute liability on the employer for employee injuries regardless of negligence. The costs are thus built into the cost of the product and are passed to the consumer. The basic purpose of the laws is to avoid litigation, lessen the expense to the claimant, and provide for a speedy and efficient means of compensating injured workers.

The first workers compensation laws were passed in Germany (1884) and England (1897). In the United States, workers compensation laws were enacted by the states shortly after the turn of the century. Workers compensation laws now exist in all 50 states.21

![]()

Principles of Workers Compensation

Although the laws of the various states differ somewhat in detail, the basic principles they embody are more or less uniform. There are five general principles on which all the laws are based.

Negligence Is Not a Factor in Determining Liability As a basic principle of law, liability for injury to another is generally based on the concept of negligence or fault. In general, without negligence, there can be no liability for injury to another.22 Workers compensation laws represent an exception to this principle and impose liability on the employer for injury to an employee that arises out of and in the course of employment regardless of fault. If the worker is injured, the employer is obligated to pay benefits according to a schedule in the law regardless of whose negligence caused the injury. The employer is considered liable without any necessary fault on his or her part and will be assessed the compensable costs of the job-related injury, not because he or she was responsible for it, caused it, or was negligent, but because of social policy. All but two laws are compulsory and require every employer subject to the law to accept the act and pay the compensation specified.23

Indemnity Is Partial but Final The second principle of workers compensation involves the amount of the benefit. The indemnity to the worker is partial, meaning the benefit is usually less than the employee might receive if he or she were permitted to sue and the employer were found to have been negligent. However, the worker is entitled to the benefits as a matter of right, without having to sue. In return for the entitlement to benefits regardless of the employer's fault, the worker gives up the right to sue the employer.24

Periodic Payments The third principle concerns the basis of payment of benefits, which is arranged to ensure a greater degree of security for the recipients. Usually, the indemnity is paid periodically instead of in a lump sum although the periodic payments may sometimes be commuted to a lump sum. The requirement of periodic rather than lumpsum settlement is designed to protect the recipient against financial ineptness and the possibility of squandering a lump sum.

Cost of the Program Is Made a Cost of Production Unlike many other social insurance coverages, the employees are not required to contribute to the financing of workers compensation coverage. The employer must pay the premium for the insurance coverage, or pay the benefits required by law, without any contribution by workers. The employer can predict the cost of accidents under a workers compensation program and build this into the price of the product, thereby passing the cost of industrial accidents on to the consumer.

Insurance Is Required As a general rule, the employer must purchase and maintain workers compensation insurance to protect against the losses covered under the law. All states require the employers coming under the workers compensation law to insure their obligations either through commercial insurance companies or a state fund or by qualification as a self-insurer. In 5 states, the insurance must be purchased from a monopolistic state insurance fund. In 20 states, the private insurance industry operates side by side with the state workers compensation insurance funds.25 Under the workers compensation insurance policy, the insurer promises to pay all sums for which the insured (i.e., the employer) is obligated under the law.

Penalties for failure to insure are severe. Forty-four states make failure to insure punishable by fines (ranging from $25 to $50,000 depending on the state), imprisonment, or both. Other laws provide that the employer may be enjoined from doing business in the state. In addition, about four-fifths of the states allow common lawsuits by the employee against a noninsuring employer.26

![]()

An Overview of State Workers Compensation Laws

Although it is difficult to generalize about state workers compensation laws, there are general similarities among the laws. The following discussion is intended to provide an overview of the laws and to identify the major areas in which the laws differ.27

Persons Covered under State Laws None of the state workers compensation laws covers all employees in the state. The most frequently excluded classes of employment are agricultural and domestic employees. Fewer than 20 states cover agricultural workers on the same basis as other categories. About half of the state laws cover domestic workers, but coverage is usually compulsory only if the worker meets certain requirements (e.g., minimum number of hours worked per week or minimum earnings). About three-fourths of the states exclude casual employees, who are those whose work is occasional, incidental, or irregular.28 In addition, about a fourth of the states have numerical limitations, providing that if the employer has fewer than a specified number of employees (ranging from two to five), the employees need not be covered under the act. The remainder of the states and the federal laws require the employer of one or more people to be covered under the law.

The laws usually permit the employer of persons omitted from the law to bring these workers under the law voluntarily. This applies to excluded classes of employment and to the employer with fewer than the number of employees specified in the law.

Injuries Covered The workers compensation laws stipulate that employee injuries are compensable only when connected with employment, requiring that the injury arise out of and in the course of employment. Usually, there is little difficulty in determining whether the injury is compensable, but problems do arise. The question may arise first whether the injured employee was “in the course of employment” at the time of the accident in cases where the injury was sustained while coming to or from the job or while the worker participated in social events connected with employment. The greater problem frequently comes up when it is clear the injury occurred in the course of employment, but there is a question whether it was caused by the employment. Injuries sustained while at work are considered to arise out of the work, but there are exceptions. Injuries may be noncompensable if they are deliberately self-inflicted or result from intoxication.29 In addition, there may be difficulties in such cases as heart attacks, mental or nervous disorders, or suicide. Often, the only way these questions can be settled is by litigation, and litigation involving these issues has been almost endless. The courts have usually taken a liberal attitude and have done their best to compensate the injured worker or his or her dependents.

Occupational Disease In addition to the traumatic type of injury, all laws provide compensation for occupational disease. All states provide coverage for all occupational diseases under a separate occupational disease law or by defining injury broadly enough under the workers compensation law to include disease. Some states have specific conditions for particular diseases, such as silicosis, asbestosis, and AIDS.

Workers Compensation Benefits There are usually seven classes of benefits payable to the injured worker or his or her dependents under the workers compensation laws:

- Medical expenses

- Total temporary disability

- Partial temporary disability

- Total permanent disability

- Partial permanent disability

- Survivors' death benefits

- Rehabilitation benefits

Medical Expense Benefits Medical expense benefits account for about 60 percent of total benefit payments under workers compensation. Medical expenses incurred through employment-related injuries are covered without limit. In an effort to control costs, many states have established medical fee schedules that limit payments to providers of medical care, and a number of states have placed limits on the employee's choice of physician.

Total Temporary Disability There are four classes of disability income benefits under the workers compensation laws. The most frequent type of disability is total temporary disability, which exists when the worker is unable to work because of an injury but will clearly recover and return to work. All states provide for a waiting period before disability benefits are payable. This waiting period is a deductible, eliminating coverage for short periods of disability, thereby reducing administrative costs. The normal waiting period is one week although some states have waiting periods as short as three days. Normally, the waiting period does not apply if the disability lasts beyond some specified number of weeks, usually four.

The amount of the benefit is set by statute and varies with the worker's wage and in some cases with the number of dependents. The most frequently used percentage of the injured worker's wage is 66⅔ percent, subject to a dollar maximum and minimum also imposed by the law. In some states, the dollar maximums and minimums are adjusted periodically by the state legislature, but in 40 states they are based on the state average weekly wage (SAWW). The minimums in these states range from 15 to 50 percent of the SAWW. Maximums range from 60 to 200 percent of the SAWW, with 100 percent being the most common. Some states provide for a sliding scale of benefits based on the number of dependents. More than 90 percent of the states provide benefits for the entire period of disability. In the remaining jurisdictions there is a time limit (ranging from 104 to 500 weeks) or a dollar limit on the benefits.

Partial Temporary Disability Many states provide disability benefits for partial temporary disability to cover those cases in which the worker cannot pursue his or her own occupation but can engage in some work for remuneration. In these cases, compensation is based on a percentage of the difference between the wages received before the injury and those received afterward. This benefit is subject to a maximum and minimum and is usually payable for the same period as total temporary disability.

Total Permanent Disability A worker is totally and permanently disabled when he or she is unable to obtain any gainful employment because of the injury and is expected to remain so. In practice, total permanent disability benefits are payable to a worker who remains disabled after exhausting total temporary disability benefits. The benefit for total permanent disability is usually computed on the same basis as the total temporary disability benefit and is subject to the same minima and maxima, but the benefits are payable for life or, in some states, for a specified number of additional weeks.

In addition to requiring the inability to obtain gainful employment, most laws specify that the loss of both hands, arms, feet, legs, or eyes, or any combination of two of these constitutes total and permanent disability.

Partial Permanent Disability An injury resulting from an industrial accident may be deemed a partial disability on one of two bases. In one instance, the loss of a member such as an arm or a leg is considered a partial permanent disability. In addition, the disability may consist of a disability of the body generally (e.g., an injured spine). In the case of a disability not involving the loss of a limb, a percentage disability is usually determined, and a benefit equal to some multiple of the weekly disability benefit as specified by law is payable for the various percentages so determined.30 The compensation for the loss of a member such as an arm or leg is usually some multiple of the weekly disability benefit, which may be commuted and paid as a lump sum (for example, 230 weeks for an arm or 125 weeks for an eye). There are wide variations among the states in the amount of compensation for the various extremities and also in the stated value of one member as opposed to another.31

In most states, the compensation for scheduled injuries is payable in addition to any benefits otherwise given the injured worker under the total temporary disability benefit. However, some states limit the total temporary disability benefit when payment is made for a scheduled injury, and a few states deduct the amount paid under total temporary disability from the allowance for the scheduled injury.

Death Benefit Benefits are payable when a worker is killed, and all laws allow two types of death benefits. Under the first, payment is made for the reasonable expenses of burial, not to exceed some maximum amount, ranging from $2000 to $15,000. The second death benefit is a survivors' benefit payable to dependents. The survivors' benefit is usually paid as a weekly sum, determined by the usual formula. Although the definition of dependent varies from state to state, most laws provide that a dependent may be a spouse, a child of the deceased worker, or a dependent parent. A child is usually defined as under 18 years of age or physically or mentally incapacitated and receiving support from the worker. The child may be natural born, adopted, a stepchild of the deceased worker, or even an unborn child if conceived before the worker's injury.

Under about three-fifths of the laws, the survivors' benefit is payable to a surviving spouse for life or until remarriage, without limit. Five states provide for a maximum number of weeks (250 to 1040), and six others set an aggregate dollar maximum. In about half the states, survivors' benefits are based on the number of dependents.

Rehabilitation Benefits Nearly all the state laws contain specific rehabilitation benefit provisions, but even when state law does not enumerate such benefits, they are provided. Under these provisions, the injured worker may be entitled to additional compensation during a period of vocational training, transportation and other necessary expenses, artificial limbs and mechanical appliances, and other benefits. The funds for payment of the rehabilitation benefits may or may not come from the employer or its insurance company. In some cases, state funds are used. In others, funds come from insurers in death cases in which no surviving dependents receive benefits. Finally, the Federal Vocational Rehabilitation Act provides for federal funds to aid states in this program.

Second-Injury Funds Under most workers compensation laws, the loss of both arms, feet, legs, eyes, or any two thereof constitutes permanent total disability. As a result, situations may arise in which an injury that is partial in nature leaves a worker totally disabled; a worker who has lost an arm or a leg in an industrial accident and who has returned to work will be totally incapacitated by another such accident. To encourage employers to hire partially disabled workers, most states established second-injury funds to cover the additional cost of a later injury. When a worker suffers a second injury that causes total permanent disability, and the injury is of a nature that would constitute only partial permanent disability but for the previous injury, the employer is liable only for the benefits payable for the partial disability. The second-injury fund pays the difference between the partial and the total permanent disability. In recent years, a number of states have repealed their second-injury funds on the basis that they are unnecessary given the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which protects disabled workers from discrimination.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

Social Security

social insurance

Old-Age, Survivors, Disability, and Health Insurance (OASDHI)

Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI)

Medicare

quarter of coverage

Federal Insurance Contribution Act (FICA) tax

fully insured

currently insured

retirement benefits

survivors' benefits

disability benefits

children's benefit

mother's (father's) benefit

parents' benefit

widow's (widower's) benefit

lump-sum benefit

averaged indexed monthly earnings (AIME)

primary insurance amount

disqualifying income

pay-as-you-go system

floor of protection

common law

employers' common-law obligations

employers' common-law defenses

contributory negligence

fellow servant rule

assumption-of-risk doctrine

casual employee

out of and in the course of employment

medical expense benefits

total temporary disability

partial temporary disability

total permanent disability

partial permanent disability

rehabilitation benefits

second-injury fund

occupational disease

absolute liability

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. Identify and briefly describe the four classes of benefits available to those covered under Old-Age, Survivors, Disability, and Health Insurance (OASDHI).

2. Explain how benefit levels are automatically adjusted under OASDHI. How are the increases in benefits financed?

3. Outline the requirements for fully insured status under OASDHI.

4. What benefits does a fully insured worker have that a currently insured worker does not?

5. What benefits does a worker who is only currently insured have?

6. Under what circumstances can a person who is entitled to Social Security benefits become ineligible for benefits?

7. Under what conditions is a children's benefit payable under Social Security? How is “child” defined for benefit purposes?

8. Explain the nature of the common-law obligations and the common-law defenses of employers' liability. Are these obligations and defenses ever used today? Under what circumstances?

9. Identify and explain the five general principles on which workers compensation laws are based.

10. Identify and briefly describe the classes of benefits that are provided to injured workers under the workers compensation laws.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. Social Security provides protection against financial loss to dependents resulting from premature death of the wage earner and provides wage earners with retirement benefits. Do you think that the enactment or expansion of the Social Security Act has adversely affected life insurance sales? Why or why not?

2. Many observers have voiced concern about the soundness of the Social Security system, pointing to the growing number of recipients and the increasing benefit levels. To what extent do you believe that the Old-Age, Survivors, Disability, and Health Insurance (OASDHI) system is in trouble? What would you recommend in the way of corrective action?

3. The OASDHI program has been called “the greatest chain letter in history.” To what aspect of the Social Security system does this probably refer? Do you agree or disagree with the observation and why?

4. The Social Security trust funds are invested in U.S. Treasury securities. Although there is little question regarding the safety of these instruments, many observers have expressed alarm over this arrangement. Do you believe that the current arrangement, in which the trust funds are invested in Treasury bonds is a good thing, a bad thing, or a matter of no consequence? Why?

5. Which, if any, of the three proposals contained in the report of the Advisory Council on Social Security released in 1997 do you personally prefer? Why?

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

AARP Public Policy Institute, Perspectives: Options for Reforming Social Security, June 2012.

Congressional Research Service, Social Security Reform: Current Issues and Legislation, November 28, 2012.

Diamond, Peter A., and Peter R. Orszag. Saving Social Security: A Balanced Approach. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2003.

Hardy, Dorcas R., and C. Colburn Hardy. Social Insecurity: The Crisis in America's Social Security System and How to Plan Now for Your Own Survival. New York: Villard Books, 1991.

Mitchell, Olivia S., Robert J. Meyers, and Howard Young, editors. Prospects for Social Security Reform. Philadelphia, Pa.: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999.

Myers, Robert J. Social Security, 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.

Rejda, George E. Social Insurance and Economic Security, 7th ed. M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2011.

Schlesinger, A. M., Jr. The Coming of the New Deal. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959.

Turner, John A. Individual Accounts for Social Security Reform: International Perspective on the U.S. Debate. W.E. Upjohn Institute, 2005.

Unemployment Insurance Reporter. New York: Commerce Clearing House, monthly updates.

U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Analysis of Workers Compensation Laws, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Chamber of Commerce, annual.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. Social Security Reform: Answers to Key Questions (GAO-05-193SP) May 2005.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| AARP Public Policy Institute | www.aarp.org/research/ppi |

| Brookings Briefing: Reforming Social Security | www.brookings.edu/research/topics/social-security |

| National Council on Compensation Insurance | www.ncci.com |

| Social Security Administration | www.ssa.gov |

| The Cato Institute Project on Social Security Choice | www.socialsecurity.org |

| The Heritage Foundation | www.heritage.org/research/social-security |

| Workers compensation.com | www.wcrinet.org |

| Workers Compensation Research Institute | www.workerscompensation.com |

![]()

1The original income protection elements of Social Security (Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance) are referred to as OASDI. The expanded system, which includes Medicare, is OASDHI. Medicare benefits are discussed in Chapter 22.

2Employees who are covered under a state or local government retirement system may elect to be included under OASDHI by referendum. Federal employees hired after December 31, 1983, are included in the OASDHI program.

3The Social Security Administration maintains an exceptionally useful Web page at http://www.ssa.gov/. The site provides current detailed information on all facets of the OASDHI program with a link to the Medicare Web site (http://www.medicare.gov).

4Calculating the number of years to include requires first calculating the number of elapsed years. Elapsed years are the years beginning the year in which the worker reached age 22 and ending with the year before the one in which the worker becomes 62, dies or is disabled. Most workers must calculate the AIME using the years of earnings equal to the number of elapsed years minus 5. For workers applying for retirement benefits, this requires 35 years of earnings (40 minus 5). Fewer years may be included if the PIA is being calculated for a worker who has died or became disabled.

5For a worker reaching age 62 in 2013, the PIA was computed on the basis of the following formula: 90 percent of the first $791 of AIME, plus 32 percent of the AIME from $791 to $4768, plus 15 percent of the AIME above $4768. The dollar amounts in the formula, known as bend points, are subject to adjustment based on changes in the national average monthly wages. See the Social Security Web site for illustrative benefits (http://www.ssa.gov). For example, an individual who has earned at least the maximum taxable wage base each year since age 22 and retires in 2013 at age 65 would receive a monthly benefit of $2414.

6A divorced spouse is entitled to receive a retirement benefit even if the worker on whose account the benefit is based continues working if both parties are at least age 62, were married for 10 years, and have been divorced for at least two years.

7Prior to 1975, the law provided only for a “mother's” benefit (i.e., a benefit to the female spouse of a retired or deceased worker with a child in her care). The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the provision of such a benefit only to females was unconstitutional and that it deprived working women of a form of protection afforded to working men.

8This formula, like the PIA formula, includes dollar bend points that are subject to adjustment based on increases in the average total wages of all workers.

9The widow's or widower's retirement benefit is reduced 19/40 of 1 percent for each month prior to full retirement age that the benefits commence (thus, a benefit equal to 71½ percent or less of the PIA at age 60).

10Disability benefits under OASDHI may be reduced if the individual also receives workers compensation benefits. The law limits combined benefits to 80 percent of the disabled person's recent earnings. Some states have reverse offset plans under which workers compensation benefits are reduced if the worker is entitled to Social Security benefits.

11In addition to the causes of disqualification listed, benefits may be lost because of conviction of treason, sabotage, or subversive activity; deportation; work in foreign countries unless that work is covered under OASDHI; and the refusal of rehabilitation by a disabled beneficiary.

12For example, children under 18 lose their benefits if they marry, regardless of whom they marry. Widows, widowers, and surviving divorced spouses lose their benefits based on the deceased worker's earnings if they remarry before age 60. Benefits to a surviving spouse or a divorced surviving spouse are not terminated if he or she remarries after age 60.

13The base amount for married taxpayers who file separate returns but who live together at any time during the year is zero.