CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Explain the special provisions of tort law applicable to automobiles

- Explain the principles of vicarious liability and the special provisions applicable to guests

- Explain the legal requirements imposed by the states regarding automobile liability insurance

- Explain the no-fault concept and the basic philosophy on which this concept is based, and evaluate the arguments for and against no-fault laws

- Explain the differences among the approaches to reform of the automobile reparations system that have been adopted by the states

- Discuss the various systems for providing insurance to high-risk drivers

- Discuss the automobile insurance classification system and how rates are affected by various underwriting factors

The automobile is the most widely owned major asset in the United States. It is also one of the chief sources of economic loss. The ownership or operation of an automobile exposes the individual to many sources of loss: a person may be killed or injured while operating a car, or may be struck by one, with resulting medical expenses and loss of income; one may be held legally liable for injuries to others or for damage to the property of others; the car may be damaged, destroyed, or stolen.

In this chapter, we begin our study of automobile insurance by examining the legal principles governing the automobile's operation, including a brief discussion of the no-fault laws that have been adopted by many states. In the next chapter, we will look at the automobile insurance policy.

Before turning to the legal environment, it may help to review the general nature of the automobile coverages available to protect against loss arising out of the automobile.

![]()

A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF AUTOMOBILE COVERAGES

![]()

For the purpose of our discussion, the reader should keep in mind the distinctions among the following four automobile insurance coverages: Automobile liability insurance, medical payments coverage, physical damage coverage, and uninsured motorists coverage.

![]()

Automobile Liability Insurance

Automobile liability insurance protects the insured against loss arising from legal liability when his or her automobile injures someone or damages another's property. This coverage is usually written with a single limit similar to that of the Homeowners Policy, but it is also written subject to “split limits,” usually expressed as $10,000/$20,000/$5000, or more simply as $10/$20/$5. The first two figures refer to the bodily injury liability limit, and the third refers to the property damage limit. Thus, $10/$20/$5 means that coverage is provided up to $10,000 for injury to one person and up to $20,000 for all persons injured in a single accident, and that property damage up to $5000 is payable for a single accident.

![]()

Medical Payments Coverage

Automobile medical payments coverage reimburses the insured and the insured's family members for medical expenses that result from automobile accidents. The protection also applies to other occupants of the insured's automobile. Like the medical payments of the Homeowners Policy, automobile medical payments coverage is distinct from the liability coverage; it applies as a special form of accident insurance. Unlike the homeowners insurance, the coverage applies specifically to the insured and members of his or her family. It is written with a maximum limit per person per accident, which usually ranges from $1000 to $5000.

![]()

Physical Damage Coverage

Automobile physical damage coverage insures against loss of the policyholder's own automobile and in this sense resembles Section I of the homeowners program. The coverage is written under two insuring agreements, (1) Other Than Collision (formerly called Comprehensive) and (2) Collision. Collision, as the name implies, indemnifies for collision losses; Other Than Collision is a form of openperils coverage that provides protection against most other insurable perils. Physical damage coverage applies to the insured auto regardless of fault. If the other driver is at fault, the insured who carries collision coverage has the option of proceeding against the other driver or collecting under his or her own collision and permitting the insurance company to subrogate. If the other driver is held liable, his or her property damage liability coverage will pay the loss.

![]()

Uninsured Motorists Coverage

Uninsured motorists coverage is an imaginative form of auto insurance under which the insurer agrees to pay the insured, up to specified limits, the amount the insured could have collected from a negligent driver who caused injury, when that driver is uninsured or is guilty of hit and run. Uninsured motorists coverage usually has the same limits as the bodily injury coverage in the liability section of the policy. Understanding the following discussion will be much easier with a firm grasp of the distinctions among these four coverages.

![]()

LEGAL LIABILITY AND THE AUTOMOBILE

![]()

The owner or operator's automobile liability is largely governed by the principles of negligence discussed in Chapter 27. However, special laws affecting automobile liability have been enacted to modify some of the basic negligence principles. Several of these statutes relate to the responsibility of others when the driver is negligent. In addition, some laws deal with the liability of the operator toward passengers.

![]()

Vicarious Liability and the Automobile

As you will recall from Chapter 27, vicarous liability describes a situation in which one party becomes liable for the negligence of another. When one thinks of being held liable for the operation of a motor vehicle, one normally has in mind a situation in which he or she is the driver. However, because of vicarious liability laws and doctrines, an individual could be held liable in situations in which someone else is the operator. First, if the driver of the automobile is acting as an agent for another person, the principal may be held liable for the agent's acts. In addition to this imputed or vicarious liability, the owner of an auto that is being operated by someone else may be held liable because of his or her own negligence, either in furnishing the auto to someone known to be an incompetent driver or in lending a car known to be unsafe. In addition to these situations based on common-law principles, vicarious liability laws have been enacted by various states that greatly enlarge the exposure of imputed liability in connection with the automobile.

Under the family purpose doctrine, applicable in 18 states and the District of Columbia,1 the owner of an automobile is held liable for the negligent acts of the members of his or her immediate family or household in their operation of the car. The family purpose doctrine is basically a part of the principal-agent relationship, in that any member of the family is considered to be an agent of the parent-owner when using the family car even for the driver's own convenience or amusement. Under a concept somewhat related to the family purpose doctrine, about half the states2 impose liability on the parents of a minor or on any person who signs a minor's application for a driver's license for any damage arising out of the minor's operation of any automobile. In this situation, it is not only driving the family car, but any car, that gives rise to the vicarious liability. Other states3 have enacted statutes that go further and make any person furnishing an auto to a minor responsible for the minor's negligent acts in the operation of the automobile. The most sweeping vicarious liability laws are the permissive use statutes, enforced in 12 states and the District of Columbia, which impose liability on the owner of an automobile for any liability arising out of someone's operating it with the owner's permission, regardless of the operator's age.4

One point bears mention again. The vicarious liability laws and doctrines do not relieve the driver of responsibility; instead, they make the other party (owner or parent) jointly liable.

![]()

Guest Hazard Statutes

The second statutory modification of legal liability principles affecting the automobile defines the liability of a driver or owner toward passengers in the car. At one time, most states had so-called guest laws, which restricted the right of a passenger in an automobile to sue the owner or the driver. The original reason for such laws was the allegation of insurers that suits by passengers presented an opportunity to defraud insurance companies. Without such laws, it was alleged, the guest in an automobile who is injured might easily induce the driver to admit liability in return for a settlement portion the driver's insurance company might make with the injured guest.

Under a standard guest law, the injured guest can collect from the negligent driver only if the driver was operating the auto in a grossly negligent manner or, in some jurisdictions, if the driver was intoxicated. Gross negligence is a “complete and total disregard for the safety of oneself or others.” Even in the case of gross negligence, the guest may be denied recovery if he or she assumes the risk involved in it. Some laws provide that the failure of the guest to protest against the grossly negligent manner in which the auto is being operated constitutes acceptance of the risk.

Although room exists for disagreement, many observers believe the guest statutes are ill-conceived laws. They were the result of a rash of state legislation in the 1920s and 1930s, the fruit of vigorous lobbying by the insurance industry. Although a few collusive suits may have been prevented over the years, tens of thousands of “guests” have been denied access to the courts for compensation recovery for their injuries. No U.S. state has adopted a new guest law for many years; in many states, the laws have been repealed or declared unconstitutional. In those states where they still exist, the courts tend to construe them more narrowly.

![]()

Automobile Liability Insurance and the Law

As late as 1971, only Massachusetts, North Carolina, and New York had compulsory automobile liability insurance laws. By 2013, every state except New Hampshire had a law requiring the owners of automobiles registered in the state to have liability insurance or, sometimes, an approved substitute form of security.5 In over 20 states, the driver must also have uninsured motorist coverage. Penalties for failure to have insurance include fines, license suspension or revocation, and, in some states, jail time. In some states uninsured drivers are prohibited from collecting noneconomic damages such as pain and suffering. In Michigan, a similar prohibition applies if the uninsured driver was 50 percent or more at fault.

Before the widespread enactment of compulsory auto insurance laws, most states attempted to solve the problem of the financial responsibility of drivers through what are known as financial responsibility laws. These laws require a driver to show proof of insurance (or some other approved form of security) when he or she is involved in an accident. Because they require proof of “financial responsibility” after an accident, these laws are sometimes called free-bite laws. Most states that have enacted compulsory auto insurance laws have retained their financial responsibility law, and drivers are subject to the requirements of both.

In most states, the financial responsibility laws take the form of a “security-type” law. It provides that any driver involved in an auto accident that causes bodily injury or damage to the property of others (the latter must exceed a specified minimum, usually $100 or $200) must demonstrate the ability to pay any judgment resulting from the accident or lose his or her license. If a driver's license is suspended, then security for future accidents must be posted before it will be restored. The financial responsibility laws apply to all parties in an accident, even those who do not appear to have been at fault. The requirements of the law are met if an insurer files a certificate (called an SR-21) indicating that, at the time of the accident, the driver had liability insurance with limits that meet the state's requirements. The required liability limits by the various states in 2013 are indicated in Table 29.1. If the driver cannot provide evidence of insurance, the law's requirements can be met by depositing security (money) with the specified authority in an amount determined by the authority. A person who does not have liability insurance and cannot make any other arrangements for settlement of the loss will lose his or her driving privileges.6 Driving privileges remain suspended until any judgment arising out of the accident is satisfied and until proof of financial responsibility for future accidents is demonstrated. Judgments are deemed satisfied, regardless of the amounts awarded, when the payment equals the required liability limits. The requirement that any judgment be satisfied may be met by filing the following with the authority: (1) signed forms releasing the driver from all liability for claims resulting from the accident; (2) a certified copy of a final judgment of nonliability; or (3) a written agreement with all claimants providing for payment in installments of an agreed amount for claims resulting from the accident. Financial responsibility for future accidents normally is proven by the purchase of automobile liability insurance in the limits the state prescribes. The insurance company then submits a certificate, an SR-22, showing the insurance is in force. Financial responsibility may be demonstrated by posting a surety bond or, as a final resort, the deposit of a stipulated amount of cash or securities (for instance, $25,000 or $50,000) with the proper authorities. The length of time for which proof is required varies from state to state, but the usual time is 3 years.

In many states, a person's driver's license may be revoked or suspended if a person is convicted of certain traffic violations. After the period of suspension, the license restoration requires proof of financial responsibility. This can be accomplished as was discussed. Offenses leading to suspension vary among the states. Nearly all states suspend licenses for driving while intoxicated, reckless driving, conviction of a felony in which a motor vehicle was used, operating a car without the owner's permission, or for a series of lesser offenses.

TABLE 29.1 State Financial Responsibility Limits, 2013

Low-Cost Auto Insurance Policies In spite of compulsory auto insurance laws, all states have some uninsured drivers, and the percentage of uninsured drivers tends to be higher in urban states where high insurance premiums may be unaffordable to some drivers. Critics of compulsory auto insurance laws have argued they force low-income drivers to buy liability insurance even though they have few or no assets to protect and need their limited incomes to pay for basic necessities of life.

California and New Jersey have created special low-cost insurance policies specifically targeted to low-income drivers with few assets to protect. To qualify for coverage in the California plan, an individual must reside in an eligible county, demonstrate financial need, and be a “good driver,” and live in a household with only good drivers.7 The vehicle's value to be insured cannot exceed $20,000. The liability limits are $10,000 bodily injury or death per person, $20,000 bodily injury for each accident and $3000 property damage for each accident. The policy satisfies California's compulsory auto insurance law even though the limits are less than the required $15/30/5. Optional Medical Payments and Uninsured Motorist Bodily Injury Coverages are available, but no Physical Damage Coverage is offered.

New Jersey has two low-cost auto insurance policies. A 1998 law enacted a series of auto insurance reforms and authorized the creation of a Basic Policy that would meet the state's compulsory auto insurance law. The Basic Policy provides $5000 per accident in property damage liability limits and Personal Injury Protection coverage (for medical expenses and lost wages) of $15,000 per person, per accident and up to $250,000 for permanent or significant injury.8 Bodily injury liability coverage is not automatically included but is available in limits of up to $10,000 per accident. In 2003, New Jersey also created “dollar-a-day” auto insurance for low-income individuals. To be eligible, an individual must be enrolled in a Medicaid program that covers hospitalization. The “dollar-a-day” policy will cover emergency treatment immediately following an accident and treatment for serious brain and spinal cord injuries up to $250,000 for the treatment of catastrophic injuries. The policy also provides $10,000 in death benefits. The policy provides first-party benefits only; there is no liability coverage. The “dollar-a-day” policy is priced at $365 per year.

![]()

Insurance for High-Risk Drivers

For most American motorists, purchasing automobile insurance is fairly routine. Although the cost of the insurance may be irritating, many insurers are willing to take the insured's premium dollars. There are some people, however, who find that insurers are generally unwilling to assume their risk and who have difficulty in obtaining automobile insurance. This is particularly true of youthful male drivers and some people who must demonstrate financial responsibility under state laws. It is also true of people whose poor driving records mark them as more hazardous risks than the average of the classification to which they would otherwise belong.

Automobile insurance companies, like most other businesses, want to make a profit or at least cover all their business operation expenses. They cannot do this if they accept many applicants whose probability of loss is greater than the average. Yet, if these high-risk drivers were to remain uninsured, their presence on the road would represent a financial risk to themselves and to others who might be involved in the same accident.

The insurance industry has been concerned that if it does not provide coverage for high-risk drivers, a government plan might be instituted to do so. If the state undertook to insure high-risk drivers, it might decide to insure standard drivers as well, and private automobile insurance might disappear. For these and other reasons, the insurance industry has established mechanisms to provide the necessary coverages for drivers who are unable to buy insurance through normal market channels. The most successful and widely used method of providing auto insurance to high-risk drivers is the Automobile Insurance Plan, operating in 44 states and the District of Columbia. Essentially, these are applicant-sharing plans under which each automobile insurance company doing business in the state accepts a share of the state's high-risk drivers. These systems were originally used in all states, but since 1972, a number of states have introduced other methods for providing such insurance.

Automobile Insurance Plans An Automobile Insurance Plan is a risk-sharing pool in which all auto insurers operating in a particular state share in writing those drivers who do not meet normal underwriting standards.9 It serves two functions. The first is to make auto liability insurance (and often other forms of auto insurance) available to those who cannot obtain it through normal channels. The second is to establish a procedure for the equitable distribution of these insureds among all the auto liability insurers in the state.10

With respect to the first function, the applicant must certify on a prescribed form that he or she has attempted, within 60 days before the application, to obtain liability insurance but without success. In most states, coverage is provided to any applicant who presents a valid driver's license. In the remaining states, certain applicants, like habitual traffic violators, are ineligible. If the applicant is eligible, a company will be assigned to underwrite the insurance. The designated insurer will be obligated to provide coverage with limits equal to the state's financial responsibility requirements. In most states, the insurer will provide limits higher than the minimum required by state law. In addition, although the plans were designed to provide only liability insurance, all the plans provide medical payments (or no-fault benefits), and most states offer Physical Damage coverage on the insured's car. An applicant cannot be assigned to a company for longer than 3 years, and the insurer may cancel an assigned risk under certain circumstances. The right to cancel is usually permitted only for nonpayment of premium, loss of the driver's license, or a number of major offenses while operating a motor vehicle.

The plan's second function is to distribute the risks equitably among all automobile insurers operating in the state. This distribution is accomplished by assigning to a particular insurer the percentage of the assigned-risk premiums that its total liability premiums bear to the total liability premiums of all automobile insurers operating in the state. Thus, if a particular company has 1/20 of all liability premiums written in the state, it would be assigned 1/20 of the risks. Although this is one of the available distribution methods, it appears to be working well.

Alternative Approaches Although the Automobile Insurance Plans exist in 44 states, 6 states use alternative systems for insuring high-risk drivers. In Maryland, the insurance is available through a state-operated fund. The remaining 5 states use one of two loss-sharing plans.

- Reinsurance Pools In New Hampshire, and North Carolina, all auto insurers participate in statewide automobile reinsurance pools, generally called the facility.11 Under this reinsurance system, every company accepts all applicants, good and bad. If the company considers a particular driver a high risk, it may place that driver in the statewide reinsurance pool. When this is done, the pool absorbs all premiums paid and losses incurred by that driver, but the originating company services the policy. The chief advantages to this system are that the stigma of purchasing insurance through an “assigned risk plan” is eliminated, and the consumer may deal with the company of his or her choice.

- Joint Underwriting Associations Michigan, Florida, and Hawaii, use a joint underwriting association (JUA) approach to provide insurance for high-risk drivers.12 Under this system, each agent or broker has access to a company designated as a servicing company for high-risk drivers. A limited number of companies provide statewide service and claim handling facilities for the high-risk drivers, but all automobile insurers in the state share in the losses. Like the reinsurance facility plans outlined, the JUA operates on the principle of sharing losses rather than sharing applicants.

Experience under the Plans As might be expected, the automobile insurance plans and the alternative loss-sharing arrangements generate losses that the alternative sources must cover. Generally, these financial losses are passed on to the other drivers in higher auto insurance rates. In a sense, the various plans all represent a continuing subsidy to problem drivers by other insureds. There tends to be a relationship between how a state regulates insurance rates in the voluntary market and the residual market's size and deficit. When insurers are unable to charge adequate rates in the standard market, the residual market's size will increase.

Distress Risk Companies Although Automobile Insurance Plans provide a mechanism for insuring high-risk drivers, some drivers are uninsurable even by the Automobile Insurance Plans and the alternative facilities in the other states. To purchase insurance coverage to meet the requirements of the state financial responsibility law, these persons must turn to what is commonly known as a distress risk company. Usually, these insurers specialize in insuring high-risk drivers. They have special ratings in which the premiums can attain almost incredible proportions and limited special policy forms. The distress risk companies perform a service, at least to the extent they are making automobile liability insurance possible at some price.

![]()

THE AUTOMOBILE INSURANCE PROBLEM AND CHANGES IN THE TORT SYSTEM

![]()

Complaints about automobile insurance are common. Almost everyone connected with the automobile insurance business has what they consider to be a legitimate grievance. Insurance companies complain when they lose money because of inadequate rates and automobile insurance fraud. The buyers complain the rates are too high. Young drivers (and to some extent older ones) complain they frequently have difficulty in obtaining coverage. Finally, many who have suffered losses maintain the settlements do not measure up to the economic loss. With all this dissatisfaction, proposals for change have found widespread support.

![]()

Criticisms of the Traditional System

Dissatisfaction with auto insurance generally has fueled a debate going on since the mid-1960s. The debate has culminated in the passage of automobile no-fault laws or other legislation reforming automobile accident reparation in about half the states. Although a part of the criticism has been aimed at insurance, some of the critics contend today's problem is not so much with insurance but rather with our method of compensating the injured. These critics maintain our tort system is wasteful, expensive, unfair, and time consuming, and they recommend we abolish it for automobile accidents.

The effectiveness and rationale of the negligence approach have been questioned since the Columbia Report of 1932,13 which pointed to the tort system's many shortcomings. One major criticism of that report, and of today's critics, is that many people who are injured remain uncompensated or are inadequately compensated. The accident victim may be unable to obtain reimbursement because he or she was contributorily negligent, because the guilty party is insolvent, or because the guilty party is unknown, as in the case of a hit-and-run driver. Additionally, the amount of compensation may depend more on the skill of the victim's attorney than on the facts. Other criticisms of our traditional system attack the high cost of operating the insurance mechanism, the contingency fee system, and the congestion of the courts that results in long delays before the injured are compensated. Furthermore, the critics maintain the traditional system is inequitable and insurers overpay small claims to avoid litigation but resist large claims in which the victim is seriously injured. Finally, the critics contend, the system is too expensive, paying more for the operation of insurance companies and the work of attorneys than it delivers to those who are injured.

For these reasons, the tort system has been under attack, and many proposals have been made to substitute a no-fault compensation system. Interest in the proposals began to grow in the middle of the 1960s, and many states have adopted no-fault laws.

![]()

The No-Fault Concept

The easiest way to understand the no-fault idea is to contrast it with the traditional tort system. Under the tort system, if you are involved in an accident and the accident is your fault, you may be held liable for injury to others or damage to their property. If you are found liable, you will be required to compensate the injured party through payment of damages. If you have liability insurance, your insurance company will pay for the other party's injuries. If the other party is found to have been negligent, his or her company will pay for your damages. If you are injured through your own negligence, you must bear the loss yourself out of existing resources or under some form of first-party insurance under which the insurance company makes direct payment to you.

Under a no-fault system, there is no attempt to fix blame or to place the burden of the loss on the party causing it; each party collects for any injuries sustained from his or her own insurance company. Under a pure no-fault system, the right to sue the driver who caused an accident would be abolished, and the innocent victim and the driver at fault would recover their losses directly from their own insurance. Compulsory first-party coverage would compensate all accident victims regardless of fault.14 Although some no-fault proposals have included abolition of tort actions for damage to automobiles, the principal focus has been on bodily injuries.

Differences among Proposals Although the basic no-fault concept is simple, several modifications of the idea have developed, and differences exist among the various proposals. We can distinguish among four different approaches:

- Pure No-Fault Proposals. Under a pure no-fault plan, the tort system would be abolished for bodily injuries arising from auto accidents. (Some proposals would abolish tort actions for damage to automobiles.) Anyone suffering loss would seek recovery for medical expenses, loss of income, or other expenses from his or her own insurer. Recovery for general damages (pain and suffering) would be eliminated.

- Modified No-Fault Proposals. Modified no-fault proposals provide limited immunity from tort action to the extent that the injured party is indemnified under a first-party coverage. Tort action is retained for losses above the amount recovered under first-party coverage. In some modified no-fault plans, payment for pain and suffering is limited or eliminated.

- Choice No-Fault.15 In a choice no-fault state, consumers are given the choice of (1) purchasing first-party coverage and having limitations placed on their ability to sue or (2) retaining their full tort rights. Those who opt for a limited right to sue are granted the protection from lawsuits provided by the state's no-fault law. Thus, within the state, there will be “tort system drivers” and “no-fault drivers.” Tort system drivers must purchase a new form of insurance coverage designed to compensate them if they are injured by a no-fault driver and their injuries fall below the threshold for lawsuits. (In that case, the tort system driver has the right to sue, but the no-fault driver has the right not to be sued.) In effect, the tort system drivers retain the option to recover noneconomic damages, but they recover them from their own insurer with a coverage that operates much the same as uninsured motorist coverage.

- Expanded First-Party or Add-On Coverage. In this case there is no exemption from tort liability. Instead, the injured party collects benefits under a first-party coverage, retaining the right to sue for losses more than the amount paid by the first-party coverage. Most important, the responsibility of the negligent driver is retained by permitting subrogation by the insurer paying the first-party benefits.

Unfortunately, the “no-fault” label is sometimes applied to all four classifications. It is a misnomer to refer to the expanded first-party coverage approach as no-fault. Plans in this category, which do not change the tort system, cannot be called no-fault plans any more than fire insurance, health insurance, or life insurance are no-fault plans. Before a plan qualifies as no-fault, the requirement that motorists carry first-party coverage to protect themselves against medical expenses and income loss must be accompanied by some restriction or outright elimination of the right to sue, together with the elimination of subrogation rights by the insurer making payment.

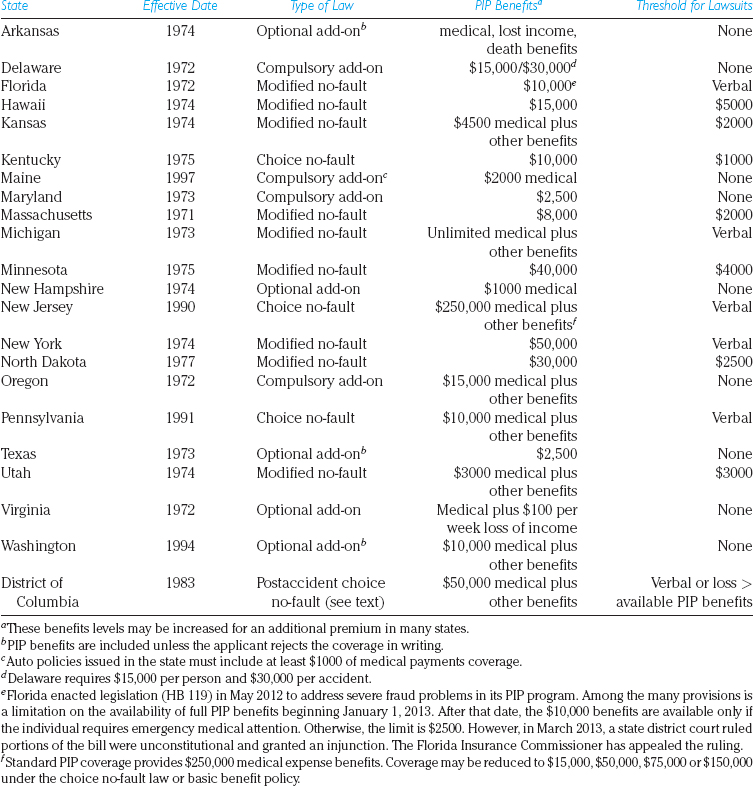

Existing State Laws By 2013, 22 states and the District of Columbia had enacted laws that modified the automobile reparation system. None of the laws that have been passed thus far is of the pure nofault variety. All the laws that have been enacted are modified no-fault laws, under which the right to sue is not totally abolished but is subject to some restriction, or they are laws requiring some form of expanded first-party coverage generally known as Personal Injury Protection (PIP) coverage.

Massachusetts became the first state with a compulsory no-fault automobile law when its legislature enacted the PIP Plan as an amendment to the state's compulsory automobile insurance law in August 1970.16 The law, a modified no-fault plan, became effective January 1, 1971. Although it did not go nearly as far as many plans that had been proposed or that have been enacted since, it did contain many elements included in early proposals and set a pattern other states followed. The first-party coverage of the Massachusetts PIP plan provides coverage up to $2000 for medical expenses, lost wages, and loss of services. Reimbursement is limited to the “net loss” of wages, with a deduction to allow for the benefits' tax-free nature. Loss of services includes coverage for reasonable expenses to replace services the injured person would have performed without pay (housekeeping, for example). The plan provides immunity from tort action up to the $2000 limit. One feature of the Massachusetts law, later copied by other states, was the provision for suits for general damages (pain and suffering) when the accident results in loss of a body member, disfigurement, or death, and when medical expenses exceed a specific dollar amount called a “threshold.” The Massachusetts law originally set its threshold at $500; it has since been raised to $2000. By 1995, a total of 16 states plus Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia had passed compulsory no-fault laws. Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, and Nevada repealed their laws. Of the 12 states remaining, 9 have modified no-fault laws, and Kentucky, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania are choice no-fault states.17 The District of Columbia has an unusual law, in which the driver elects either no-fault benefits or fault-based coverage. However, after an accident, the driver has 60 days to decide to forgo the no-fault benefits and to sue the other party. Several states have enacted laws that are frequently called “no-fault” but are expanded first-party or add-on systems, with no restrictions on lawsuits. In three states, the add-on coverage is compulsory. In Arkansas, it is optional, but the driver must explicitly reject it. In the remaining states, add-on benefits are available, but the individual must voluntarily elect the coverage, and, there are no restrictions on lawsuits. All these plans provide for subrogation by the insurer paying the first-party benefits.

Table 29.2 lists the no-fault and add-on laws in effect in 2013. There are vast differences among the no-fault laws in benefit levels and in the tort exemption. Benefits range from $8000 in Massachusetts to unlimited in Michigan.18 The modified no-fault and choice no-fault laws all permit accident victims to sue for general damages. In seven states, the threshold is monetary, and lawsuits are permitted when medical costs exceed a certain threshold level, ranging from $1000 to $4000. The remaining five states use a verbal threshold or a combination of a dollar and verbal threshold. In a verbal threshold state, lawsuits are permitted for serious injuries, with the specific definition of “serious” depending on the state. A typical definition will encompass injuries that are significant and permanent or resulted in death.19 Dollar and verbal thresholds, above which tort action is permitted for general damages, represent legislative compromises with the no-fault principle.

TABLE 29.2 Automobile No-Fault and Expanded First-Party (Add-On) Benefit Laws

In most states, the no-fault statute applies only to private passenger automobiles and excludes trucks and motorcycles. Only one state applies the no-fault principle to property damage. In Michigan, vehicle owners are responsible for damage to their own automobiles, with suits between drivers for recovery of collision damage forbidden. Damage to property other than automobiles remains under the tort system.

Cost Experience in No-Fault States There is an understandable interest in the cost experience of those states with no-fault plans, but comparing costs is difficult because of other changes in the insurance environment. Proponents argued that the savings from eliminating litigation costs and recovery for pain and suffering would enable all injured personsm regardless of fault, to collect for their economic losses (i.e., medical expenses and lost wages), and this could be done without increasing total premiums. Premium reductions were mandated in many states when the no-fault laws were first passed.

Opponents of no-fault argued that although the plans were sold on the promise they would cut premiums, the reverse would happen. Most states have enacted low thresholds for lawsuits, thus failing to eliminate costs for litigation and pain and suffering.20 In these “weak no-fault” states, lawsuits are not eliminated, and no-fault benefits are added. Thus, total costs increase. Furthermore, low dollar thresholds may encourage fraud by giving people an incentive to artificially increase their losses to exceed the threshold (e.g., by seeking unnecessary medical care). These proponents argue for strengthening state no-fault laws rather than eliminating them.

While comparing costs is difficult because of other differences in the insurance environment, recent evidence has been disappointing for no-fault proponents. Premiums have increased in all states, and there is some evidence that the increases have been the largest in states that have restricted the right to sue.21 Much of this increase stems from differences in medical costs. Fraud has been a cost-driver, and most current reform efforts focus on prevention, detection, and increased penalties for fraud.

No-fault Fraud No-fault fraud have been identified as a particular problem in Florida, New York, and Michigan. In December 2011, the Florida Insurance Consumer Advocate reported significant fraud in the state's no-fault system had increased premiums, amounting to a “fraud tax” of nearly $1 billion. Problems included staged accidents, questionable medical claims, and increased litigation. Medical claims had skyrocketed, with chiropractic care, physical therapy, and massage therapy the most frequently billed services. Lawsuits were increasing, and there was evidence of a relationship between some attorneys and “PIP clinics.” In 2012, Florida enacted HB 119 to target PIP fraud. It strengthened licensing requirements for clinics that receive PIP reimbursement, eliminated coverage for massage therapists and acupuncturists, increased penalties for health care providers who commit fraud, and gave insurers more time to investigate questionable claims. The law also reduced PIP benefits (from $10,000 to $2500) for individuals not requiring emergency medical care and required them to seek medical treatment within 14 days of the accident. The law's constitutionality was challenged, and an injunction was ordered in March 2013, preventing implementation of some features. As of June 2013, its fate was unclear.

In March 2012, New York Governor Cuomo announced a statewide effort to shut down “medical mills” that increased NY PIP costs. The announcement followed the arrests of 36 people (including 10 licensed physicians and three attorneys) in connection with a massive no-fault fraud ring that had billed insurers more than $275 million in fraudulent charges, reportedly the largest no-fault fraud case in history. The suspects, many of whom have since pled guilty, set up more than 100 bogus medical clinics to bill insurers. The NY Department of Financial Services (DFS), which regulates insurance, found evidence of doctors and other health care providers providing unnecessary treatment and of providers renting their tax ID number to fraudulent medical practices that submitted fake bills to insurance companies. In 2012, the DFS announced an investigation of 135 providers with suspicious billing practices and issued new regulations targeted at the problem.

In 2012, Michigan enacted anti-fraud legislation making it a felony to act or employ a “runner” to recruit people for staged accidents or other insurance fraud. In April 2013, Governor Snyder proposed reforms including replacing the unlimited medical benefits with a $1,000,000 limit, and creating a special fraud bureau to target no-fault fraud.

Prospects of Further No-Fault Legislation Most no-fault laws were introduced during the 1970s. During that period, there was also serious discussion of a national no-fault system, and members of Congress introduced several bills to create such a system. After the 1970s, little activity occurred until the 1990s when auto insurance rates were soaring in some states. States began to assess the results of the existing no-fault laws, and some state repealed them. Georgia repealed its no-fault law in 1991, and Connecticut repealed its law in 1993. New Jersey and Pennsylvania switched to choice no-fault laws during the 1990s, and in 2003, Colorado let its law lapse due to rising premiums. In 1997, legislation was introduced in Congress to create a national system of choice no-fault, but it was not enacted.22 Given the experience in no-fault states, it seems unlikely other states will adopt no-fault programs in the foreseeable future. States with no-fault laws will continue to pursue efforts to reduce premiums, particularly focused on controlling increases in medical costs.

![]()

AUTOMOBILE INSURANCE RATES

![]()

Over the years, competition and a desire to avoid adverse selection has led insurers to greater refinement of their rating systems. One of the earliest examples of this occurred in the 1922 when a former Illinois farmer, George Mecherle, decided to start a mutual insurance company for farmers. He believed the existing insurers were overcharging farmers by basing their premiums on the higher accident rates in the city. Today that company, State Farm, holds the largest market share in automobile insurance.

At one time, insurance premiums in most states were based on a fairly standard set of factors. These included the driver's age, gender, and marital status, how the automobile was used (for pleasure only, driving to work less than 15 miles each way, driving to work more than 15 miles each way, business use, or farm use), and the individual's driving record (previous accidents and violations of traffic laws). In addition to these factors, the rates varied with the territory in which the automobile was principally garaged (with urban locations tending to cost more than rural areas), the limits of coverage desired, and, for physical damage coverages, the value of the automobile and the deductible selected. Many companies offered discounts for youthful drivers who had completed an approved driver training course and for students with good grades.

These factors are still important, but, today, insurers use a variety of additional factors. Better access to data and increased computing power have enabled greater statistical analysis (known as predictive analytics). By analyzing historical claims experience and other information, insurance companies have identified other factors that can help to predict future losses, including, for example, credit history, occupation, level of education, and whether the applicant has had previous coverage. Insurers are using these findings to produce more refined rating classes. Insurance companies hire actuaries and statisticians to analyze the data and produce rating systems that optimize data use in predicting the losses of a group of insureds.

Insurers may also draw from external information sources to understand the risk posed by an individual driver. For example, a more granular understanding of the geographic risk can be obtained by assessing the traffic density where the automobile is principally garaged, the nature of that traffic, and the weather. This information may be obtained from third parties.23

Telematics The most recent development in automobile insurance rating is telematics, in which the insurer gathers information on the use of automobiles through “black boxes” in the autos. Early efforts to use telematics began in the 1990s. In 1998, Progressive Insurance Company introduced a pilot program known as the Pay-As-You-Drive program. If an insured chose to participate, Progressive would gather information from a global positioning system (GPS) installed in the auto, including how much, at what time, and where the insured drove. This information was used to adjust the insured's premium. Although the participants reportedly liked the program and saved an average of 25 percent of their previous premium, the number of participants was low, and Progressive discontinued selling new policies in April 2000.

In 2003, Norwich Union introduced a “Pay-As-You-Drive” program in England, based on the Progressive program by the same name.24 In Norwich Union's program, the company received a regular stream of information on the insured's driving habits, including how often, when, and where he or she drove. Premiums were based on a fixed monthly fee plus costs based on the miles driven (similar to a mobile phone bill). The per mile charge varied by insured and by the time of day (Peak vs. Off-Peak) and type of road.

Today, more insurers in the United States are embracing telematics. In 2004, Progressive reintroduced telematics when it began a pilot project in Minnesota. In this case, a TripSensor installed in the auto recorded mileage, time, and the speed at which customers drove. Data were uploaded to the insurance company once a month and used to adjust the insured's rates.

Telematics has proven popular with parents of teenage drivers, who find it useful to have detailed information on their child's driving habits when they are absent. In April 2007, AIG Auto Insurance announced it was launching a GPS-Based Teen Driver Pilot Program in six states. Under the program, AIG offered its insureds GPS systems for a teen driver's car at reduced rates. This allowed the parents to determine the location of the teen's car at any time. The program would automatically send the parent an e-mail and/or text message if the teen's car exceeded predefined speed limits or was driven too far from a predefined location.

A device installed in the vehicle can collect information on the amount of driving and when and where it took place. More comprehensive telematics programs will collect information on items such as driving speed, braking patterns, and other behaviors. By analyzing the data collected across all drivers, insurers gain a better understanding of how different behaviors contribute to loss experience. This may be used to vary the premiums of individuals who are enrolled in a telematics (“pay as you drive”), or it may be used to establish premiums for individuals who are not in a telematics program but share similar characteristics.

Some experts predict that, in the future, insurance companies may regularly access information contained in an automobile's data recorder, or “black box”, that is increasingly being included in the auto by automobile manufacturers.25 Others believe that concerns about privacy will limit acceptance of black-box technology for insurance rating in the United States. In the future, insurers may be able to collect information, such as seat belt usage and driving habits (e.g., speed driven, how the brakes are applied) as well as when, where, and how much the auto is driven. The implications for insurance ratemaking are enormous.

Differences in Premiums The various factors used to determine the final premium can yield wide differences in premiums for different drivers, with some insureds paying more for their insurance than others. Insurance rating factors have periodically come under criticism. While most people accept the idea that better drivers should pay less, some question the validity of those factors that do not directly relate an individual's own loss experience. So, for example, most people would agree that those who have had accidents or traffic violations should pay more. Many would agree that years of driving experience is an appropriate factor. Some, however, object to the use of factors such as age, gender, and location of the vehicle, arguing that an individual has no control over those factors. Credit score, occupation, and education have been subject to criticism.

As we discussed in Chapter 6, there has been some resistance to the use of some rating factors. Some states prohibit the use of gender in setting auto insurance rates. More recently, some states have placed restrictions on the ability of insurers to use credit scores.26 In 2012, the Consumer Federation of America raised concerns about the fairness of some rating factors (particularly education and occupation.) As the rating system evolves, the debate over the methods insurance companies use to set rates will continue. Given the increasing use of telematics, insurance premiums in the future may be determined more by an individual's driving behavior than by imperfect proxies, such as gender and age.

![]()

THE SHIFTING VIEW OF AUTO INSURANCE

![]()

The increasing cost of automobile insurance and the difficulty that some drivers have in obtaining coverage have raised automobile insurance to the status of a major social problem. At least a part of this problem stems from the seldom mentioned shift in the way that society views automobile insurance.

Originally, auto liability insurance, like personal liability insurance, was designed to protect the person insured against financial loss arising out of torts. When legislatures acted to make liability insurance compulsory, the motivation was not a paternalistic attempt to ensure drivers were protected against lawsuits. Rather, it was an attempt to provide injured persons with a defendant who is worth suing. Imperceptibly, the function of auto liability insurance changed. Although it still provides protection for insureds against liability losses, compulsory auto liability insurance is viewed as a form of protection for accident victims. With this shift in objectives, there has been an understandable shift in the attitude of consumers toward auto insurance.

Under the compulsory auto insurance system, some people are forced to purchase a product they neither want nor need. They purchase insurance not for their own protection but for the benefit of those they might injure. Economically disadvantaged people in particular have developed an animosity toward automobile insurance. It is a product from which they derive little benefit. After all, a person who does not have anything can afford to lose it. In the absence of a legal requirement, people who have little to lose in a lawsuit would “take their chances” driving without insurance.

Ironically, compulsory auto insurance does not solve the problem. The compulsory levels of protection are inadequate to protect many people who might be injured, especially persons with higher incomes. Despite the compulsory laws, many people must purchase coverage to protect against losses they might suffer that are in excess of the auto limits carried by drivers with minimum limits.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

automobile liability insurance

automobile medical payments

coverage

automobile physical damage

coverage

uninsured motorists coverage

family purpose doctrine

permissive use statutes

guest laws

compulsory automobile liability

insurance laws

financial responsibility laws

free-bite laws

SR-21

SR-22

Automobile Insurance Plan

Assigned Risk Plans

reinsurance facility

joint underwriting associations

distress risk company

no-fault

modified no-fault

choice no-fault

expanded first-party coverage

threshold level

telematics

rating factor

predictive modeling

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. What are the three major classes of loss associated with the ownership or operation of an automobile? What types of insurance coverage protect against each? What automobile coverages protect against each?

2. Briefly describe the general provisions of a financial responsibility law. Why are these laws often called “free-bite laws”?

3. Briefly distinguish between an SR-21 and an SR-22 that must be filed with the state department of motor vehicles under a financial responsibility law.

4. What is the purpose and general nature of an Automobile Insurance Plan?

5. Outline the various ways in which one may be held vicariously liable in the operation of an automobile.

6. Describe the distinguishing characteristics of the four approaches currently used to provide automobile liability insurance to drivers who are unacceptable to insurers in the normal course of business.

7. Briefly describe the criticisms of the tort system that led to the enactment of automobile no-fault laws.

8. In what way is the automobile no-fault concept similar to workers compensation? In what way is it different?

9. List and briefly explain the differences among the three major approaches that automobile accident reparation reform legislation may take.

10. Briefly explain the major factors that are considered in determining the premium for automobile liability insurance and how ratemaking is evolving.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. How do you personally think we should cope with the problem of bad drivers who have difficulty obtaining insurance through normal market channels?

2. Some states have guest hazard statutes. Do you think these laws are a logical extension of the risk doctrine assumption, or should they be repealed?

3. What, in your opinion, is the strongest argument in favor of a no-fault system for compensating the victims of automobile accidents? What is the strongest argument against such a system?

4. Many people in the property and liability insurance industry complain about the “automobile problem.” The “automobile problem” consists of a series of interrelated problems. What factors have combined to produce a problem in the automobile insurance area?

5. The insurance mechanism is based on the principle of loss-sharing, with those who do not suffer losses paying to meet the costs of those who do. In view of this principle, would it make more sense to group all ages together for rating purposes, with older drivers subsidizing the cost of the losses incurred by younger drivers? Explain why insurance companies divide drivers into different classifications with preferential rates for some groups.

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Anderson, James M., Paul Heaton, and Stephen J. Carroll. The U.S. Experience with No-Fault Automobile Insurance: A Retrospective. Rand Institute for Civil Justice, 2010. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG860.html.

Athavale, Manoj and Shaheen Borna. “Some Issues for Insurers in the Use of Event Data Recorders.” Journal of Insurance Issues 3(1), 2008.

Cole, Cassandra R., Kevin L. Eastman, Patrick F. Maroney, and Kathleen A. McCullough. “A Review of the Current and Historical No-Fault Environment,” Journal of Insurance Regulation, Fall 2004, Vol. 23: pp. 3–23.

Cook, Mary Ann. Personal Risk Management and Property-Casualty Insurance, Malvern, Pa.: American Institute for Chartered Property Casualty Underwriters/Insurance Institute of America, 2010.

Fire, Casualty, and Surety Bulletins, Personal Lines Volume. Erlanger, Ky.: National Underwriter Company. Available electronically at: http://cms.nationalunderwriter.com/.

Tennyson, Sharon. The Long-Term Effects of Rate Regulatory Reforms on Automobile Insurance Markets. Insurance Research Council, 2012.

Widiss, Alan I., and Jeffrey E. Thomas. Uninsured and Underinsured Motorist Insurance, 3rd ed. Anderson Publishing, 2005.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| Best's Review | www.bestreview.com |

| Information Information Institute | www.iii.org |

| ISO, A Verisk Company | www.iso.com |

| National Underwriter | www.nationalunderwriter.com |

![]()

1Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Washington, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

2Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin.

3Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Pennsylvania, and Utah.

4California, Connecticut, Florida, Idaho, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and the District of Columbia.

5The most recent state to adopt a compulsory auto insurance law was Wisconsin in 2010.

6The financial responsibility law of a particular state applies to nonresidents who have accidents in the state. The suspension of the license and registration of a nonresident normally affects driving privileges only in that state. However, some states have reciprocal provisions, and if the nonresident's home state has reciprocity, his or her license and registration will be suspended in the home state as well.

7The insurance commissioner must determine that coverage is needed before a county is permitted to participate in the program. By the end of 2007, policies were available in all counties. The program is administered by the California Automobile Assigned Risk Plan.

8Personal Injury Protection provides first-party benefits for medical expenses and lost wages. It is described in more detail in the discussion of no-fault automobile laws later in this chapter.

9These plans were originally called Assigned Risk Plans, but the name was changed to eliminate the stigma of being insured through a mechanism with “risk” in its title.

10Automobile Assigned Risk Plans were organized by insurers as voluntary risk-sharing mechanisms but were later made compulsory. A U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1951 upheld the constitutionality of compulsory assigned risk plans in California State Automobile Association Inter-Insurance Bureau, Appellant, v. John R. Maloney, Insurance Commissioner, 340 U.S. 105; 71 Sup. Ct. 601; 95 Law Ed. 788.

11South Carolina had a reinsurance facility from 1975 to 1999. A consumer backlash against the increasing assessments to cover the facility's deficits led to the enactment of a comprehensive set of regulatory reforms, most of which became effective in 1999. In 1999, the facility was temporarily replaced with a joint underwriting association, which was converted to an Automobile Insurance Plan in 2003. At one point (1992), the facility insured more than 40 percent of South Carolina's drivers. Its cumulative deficit over the 20+ years in existence was $2.4 billion.

Massachusetts previously had a reinsurance facility, but it converted to an automobile insurance plan between 2008 and 2009.

12New Jersey established a joint underwriting association known as the New Jersey Automobile Full Underwriting Association in 1984. By 1990, the JUA insured more than half of the state's drivers and had accumulated a deficit of over $3 billion. The Fair Auto Insurance Reform Act of 1990 resulted in the creation of an Automobile Insurance Plan in 1992.

Missouri had a JUA until September 2008 when it was replaced by the Missouri Automobile Insurance Plan.

13Columbia Council for Research in the Social Sciences, Report by the Committee to Study Compensation for Automobile Accidants (New York: Columbia University, 1932).

14No-fault insurance is frequently described as being “just like workers compensation insurance.” Those who draw this analogy misunderstand the no-fault concept, the nature of workers compensation insurance, or perhaps both. As the student will recall, workers compensation involves absolute liability and requires the employer to compensate injured workers without regard to fault. No-fault is almost diametrically the opposite; the person suffering the injury is responsible for his or her own loss. No-fault would be “just like workers compensation” if individual workers were required to purchase insurance to protect themselves against injuries suffered on the job, and the employer were released from all liability.

15Choice no-fault was proposed by Jeffrey O'Connell, one of the authors of the Keeton-O'Connell Basic Protection Plan, in 1965, and by Robert J. Joost in a 1986 article in the Virginia Law Review.

16Although Massachusetts enacted the first state law, Puerto Rico had a government-administered and tax-supported no-fault system in 1969. The Social Protection Plan of Puerto Rico provides unlimited medical expenses and modest loss of income benefits. Private insurers do not participate in the plan.

17Pennsylvania had an earlier no-fault law that became effective in 1975. This law was repealed in 1984, then replaced by a choice no-fault law in 1990. The 1990 law requires motorists to select between a full-tort alternative under which they are allowed to seek compensation through the courts for economic and noneconomic loss, and a limited-tort alternative, under which they may sue for noneconomic loss only in the event of serious injury.

The process for making an election for no-fault depends on the states. In New Jersey and Kentucky, drivers are presumed to have elected no-fault unless they specifically reject it. In Pennsylvania, a driver is assumed to want no limit on his or her ability to sue unless he/she specifically requests no-fault.

18Michigan PIP benefits include unlimited medical expenses plus limited lost wages, replacement services (for daily living activities the insured previously did but must now hire someone else to do), survivor loss benefits (payable to dependents who because of the accident are deprived of economic support from the insured), and funeral and burial expenses. Puerto Rico also has a modified no-fault law, adopted in 1970, with unlimited medical benefits.

19New York has a verbal and dollar threshold. Injured individuals may sue for noneconomic damages if the severity of their injuries satisfies the verbal threshold or if the cost of the claim exceeds $50,000.

20New Jersey's initial no-fault law permitted suits for pain and suffering if a person incurred as little as $200 in economic loss.

21See, e.g., Anderson, James M., Paul Heaton, and Stephen J. Carroll. The U.S. Experience with No-Fault Automobile Insurance: A Retrospective. Rand Institute for Civil Justice, 2010. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG860.html

22The Auto Choice Reform Act of 1997 would have created a choice no-fault system under which states would have the option of opting out. If a state failed to opt out, a choice no-fault system would be created in the state, giving consumers the ability to choose between tort and no-fault. Although the legislation was sponsored by leading Republicans (especially House Majority Leader Dick Armey, R-Tex.), it drew bipartisan sponsorship.

23In 2013, ISO released the ISO Advanced Rating Toolkit for personal auto insurance. The Toolkit includes ISO's Risk Analyzer suite of predictive modeling tools, which uses hundreds of indicators to predict expected losses for an individual policy and coverrage. Insurers are can use output from the Risk Analyzer directly or as variables in their own predictive models.

24Progressive had received a patent for the program in 2000, and it licensed the patent to Norwich Union for its program.

25The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) estimated that about 64 percent of 2004 model passenger vehicles were equipped with event data recorders (EDRs), which record information immediately before and after a crash. In August 2006, NHTSA issued a rule that standardized the information collected by EDRs for 2011 and later models. EDRs must collect at least 15 data elements, including the vehicle's speed, whether the brake was applied, and the driver's seat belt status. This information has been used in litigation over who is at fault in an automobile accident. Advanced EDRs may collect as many as 30 extra data elements.

26In 2003, more than 60 bills to restrict insurers' ability to use credit scores in underwriting and rating were introduced in 33 states. Although most of them did not pass, most states have some regulation concerning the use of credit scores by insurance companies.