CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Define insurance from the viewpoint of the individual and of society

- Identify and explain the two essential features in the operation of insurance

- Explain how the law of large numbers supports the operation of the insurance mechanism

- Identify and explain the desirable elements of an insurable risk

- Explain what is meant by adverse selection and why it is a problem for insurers

- Explain the economic contributions of insurance

![]()

THE NATURE AND FUNCTIONS OF INSURANCE

![]()

As we have seen, there are a number of ways of dealing with risk. In this book, we are concerned primarily with the most formal of these various approaches. We turn now to an examination of the insurance device, focusing on its nature and the manner in which it deals with risk.

![]()

Risk Sharing and Risk Transfer

Insurance is a complicated and intricate mechanism, and it is consequently difficult to define. However, in its simplest aspect, it has two fundamental characteristics:

- Transferring or shifting risk from one individual to a group

- Sharing losses, on some equitable basis, by all members of the group

To illustrate the way in which insurance works, let us assume there are 1000 dwellings in a given community and, for simplicity, that the value of each house is $100,000. Each owner faces the risk that his or her house may catch on fire. If a fire occurs, a financial loss of up to $100,000 could result. Some houses will undoubtedly burn, but the probability that all will burn is remote. Now, let us assume that the owners of these dwellings enter into an agreement to share the cost of losses as they occur, so no single individual will be forced to bear an entire loss of $100,000. Whenever a house burns, each of the 1000 owners contributes his or her proportionate share of the amount of the loss. If the house is a total loss, each of the 1000 owners will pay $100 and the owner of the destroyed house will be indemnified for the $100,000 loss. Those who suffer losses are indemnified by those who do not. Those who escape loss are willing to pay those who do not because, by doing so, they help eliminate the possibility that they themselves might suffer a $100,000 loss. Through the agreement to share the losses, the economic burden of the losses is spread throughout the group. This is essentially the way insurance works, for what we have described is a pure assessment mutual insurance operation.

There are some potential difficulties with the operation of such a plan. Most obviously, some members of the group might refuse to pay their assessment at the time of a loss. This problem can be overcome by requiring payment in advance. To require payment in advance for the losses that may take place, it will be necessary to have some idea as to the amount of those losses. This may be calculated on the basis of past experience. Let us now assume that on the basis of past experience, we are able to predict with reasonable accuracy that 2 of the 1000 houses will burn. We could charge each member of the group $200, making a total of $200,000. In addition to the cost of the losses, there would be some expenses in the operation of the program. Also, a possibility exists that our predictions might be inaccurate. We might, therefore, charge each member of the group $300 instead of $200, thereby providing for the payment of expenses and also providing a cushion against deviations from our expectations. Each of the 1000 homeowners will incur a small certain cost of $300 in exchange for a promise of indemnification in the amount of $100,000 if his or her house burns down. This $300 premium is, in effect, the individual's share of the total losses and expenses of the group.

![]()

Insurance Defined from the Viewpoint of the Individual

Based on the preceding description, we may define insurance from the individual's viewpoint as follows:

From an individual point of view, insurance is an economic device whereby the individual substitutes a small certain cost (the premium) for a large uncertain financial loss (the contingency insured against) that would exist if it were not for the insurance.

The primary function of insurance is the creation of the counterpart of risk, which is security. Insurance does not decrease the uncertainty for the individual as to whether the event will occur, nor does it alter the probability of occurrence, but it does reduce the probability of financial loss connected with the event. From the individual's point of view, the purchase of an adequate amount of insurance on a house eliminates the uncertainty regarding a financial loss in the event that the house should burn down.

Some people seem to believe that they have somehow wasted their money in purchasing insurance if a loss does not occur and indemnity is not received. Some even feel that if they have not had a loss during the policy term, their premium should be returned. Both viewpoints constitute the essence of ignorance. Relative to the first, we know that the insurance contract provides a valuable feature in the freedom from the burden of uncertainty. Even if a loss is not sustained during the policy term, the insured has received something for the premium: the promise of indemnification if a loss had occurred. With respect to the second, one must appreciate that the operation of the insurance principle is based on the contributions of the many paying the losses of the unfortunate few. If the premiums were returned to the many who did not have losses, there would be no funds available to pay for the losses of the few who did. Basically, the insurance device is a method of loss distribution. What would be a devastating loss to an individual is spread in an equitable manner to all members of the group, and it is on this basis that insurance can exist.

![]()

Risk Reduction Through Pooling

In addition to eliminating risk at the level of the individual through transfer, the insurance mechanism reduces risk (and the uncertainty related to risk) for society as a whole. The risk the insurance company faces is not merely a summation of the risks transferred to it by individuals; the insurance company is able to do something that the individual cannot, and that is to predict within rather narrow limits the amount of losses that will occur. If the insurer could predict future losses with precision, it would face no possibility of loss. It would collect each individual's share of the total losses and expenses of operation and use these funds to pay the losses and expenses as they occur. If the predictions are inaccurate, the premiums the insurer has charged may be inadequate. The accuracy of the insurer's predictions is based on the law of large numbers. By combining a sufficiently large number of homogeneous exposure units, the insurer is able to make predictions for the group as a whole using the theory of probability.

Probability Theory and the Law of Large Numbers Probability theory is the body of knowledge concerned with measuring the likelihood that something will happen and with making predictions on the basis of this likelihood. The theory deals with random events and is based on the premise that although some events appear to be a matter of chance, they occur with regularity over a large number of trials. The likelihood of an event is assigned a numerical value between 0 and 1, with those that are impossible assigned a value of 0 and those that are inevitable assigned a value of 1. Events that may or may not happen are assigned a value between 0 and 1, with higher values assigned to those estimated to have a greater likelihood or “probability” of occurring.

At this point, it may be useful to distinguish between two interpretations of probability:

- The relative frequency interpretation. The probability assigned to an event signifies the relative frequency of its occurrence that would be expected given a large number of separate independent trials. In this interpretation, only events that may be repeated for a “long run” may be governed by probabilities.

- The subjective interpretation. The probability of an event is measured by the degree of belief in the likelihood of the given incident's occurrence. For example, the coach of a football team may state that his team has a 70 percent chance of winning the conference title, a student may state that he or she has a 50:50 chance of getting a B in a course, or the weather forecaster may state that there is a 90 percent chance of rain.

Both of these interpretations are used in the insurance industry, but for the moment let us concentrate on the relative frequency interpretation.

Determining the Probability of an Event To obtain an estimate of the probability of an event in the relative frequency interpretation, one of two methods can be used. The first is to examine the underlying conditions that cause the event. For example, if we say that the probability of getting a “head” when tossing a coin is .5 or ½, we have assumed or determined that the coin is perfectly balanced and that there is no interference on the part of the tosser. If we ignore the absurd suggestion that the coin might land on its edge, there are only two possible outcomes, and these are equally likely. Therefore, we know that the probability is .5. In the same manner, we know that the probability of rolling a six with a single die is ![]() or that the probability of drawing the ace of spades from a complete and well-shuffled deck is

or that the probability of drawing the ace of spades from a complete and well-shuffled deck is ![]() . These probabilities are deducible or obvious from the nature of the event. Because they are determined before an experiment in this manner (i.e., on the basis of causality), they are called a priori probabilities.

. These probabilities are deducible or obvious from the nature of the event. Because they are determined before an experiment in this manner (i.e., on the basis of causality), they are called a priori probabilities.

These a priori probabilities are of little significance for us except insofar as they can be used to illustrate the operation of the law of large numbers. Even though we know that the probability of flipping a head is .5, we also know we cannot use this knowledge to predict whether a given flip will result in a head or a tail. We know the probability has little relevance for a single trial. Given a sufficient number of flips, however, we would expect the result to approach one-half heads and one-half tails. We feel this is true even though we may not have the inclination to test it. This commonsense notion that the probability is meaningful only over a large number of trials is an intuitive recognition of the law of large numbers, which in its simplest form states the following:

The observed frequency of an event more nearly approaches the underlying probability of the population as the number of trials approaches infinity.

In other words, for the probability to work itself out, a large number of flips or tosses are necessary. The greater the number of trials or flips, the more nearly the observed result will approach the underlying probability of .5.

Clearly, this a priori method of determining the probability of an event is the preferred method. Except in the most elementary situations, determining causality is not practical. Therefore, another approach is employed. When we do not know the underlying probability of an event and cannot deduce it from the nature of the event, we can estimate it on the basis of past experience. Suppose we are told the probability that a 21-year-old male will die before reaching age 22 is .001. What does this mean? It means that someone has examined mortality statistics and discovered that, in the past, 100 men out of every 100,000 alive at age 21 died before reaching age 22. It also means that, barring changes in the causes of these deaths, we can expect approximately the same proportion of 21-year-olds to die in the future.

Here, the probability is interpreted as the relative frequency resulting from a long series of trials or observations, and it is estimated after observation of the past rather than from the nature of the event, as in the case of a priori probabilities. These probabilities, computed after a study of past experience, are called a posteriori or empirical probabilities. They differ from a priori probabilities, such as those observed in flipping a coin, in the method by which they are determined but not in their interpretation. In addition, whereas the probability computed prior to the flipping of a coin can be considered to be exact, probabilities computed on the basis of past experience are only estimates of the true probability.

The law of large numbers, which tells us that a priori estimates are meaningful only over a large number of trials, is the basis for the a posteriori estimates. Since the observed frequency of an event approaches the underlying probability of the population as the number of trials increases, we can obtain a notion of the underlying probability by observing events that have occurred. After observing the proportion of the time that the various outcomes have occurred over a long period of time under essentially the same conditions, we construct an index of the relative frequency of the occurrence of each possible outcome. This index of the relative frequency of each of all possible outcomes is called a probability distribution, and the probability assigned to the event is the average rate at which the outcome is expected to occur.

In making probability estimates on the basis of past experience or historical data, we make use of the techniques of statistical inference, which is to say that we make inferences about the population based on sample data. It is usually impossible to examine the entire population, so we must be content with a sample. We take a sample to draw a conclusion about some measure of the population (referred to as a parameter) based on a sample value (called a sample statistic). In attempting to estimate the probability of an event, the parameter of the population in which we are interested is the mean or average frequency of occurrence, and we attempt to estimate this value based on our sample. Because only partial information is available, we confront the possibility that our estimate of the mean of the population (the probability) will be wrong.

We know that the observed frequency of an event will approach the underlying probability as the number of trials increases. It, therefore, follows that the greater the number of trials examined, the better will be our estimate of the probability. The larger the sample on which our estimate of the probability is based, the more closely our estimate should approximate the true probability.

Unfortunately, it is seldom possible to take as large a sample as we would like. Instead, we make an estimate (called a point estimate) of the mean of the population based on the mean of the sample and then estimate the probability that the mean of the population falls within a certain range of this point estimate. Put differently, we estimate the population mean on the basis of the sample, and then we allow a margin for error. The extent of the margin for error will depend on the concentration of the values that make up the mean and the size of the sample. The greater the dispersion of the individual values from the mean (i.e., the greater the variation in data on which the sample mean is based), the less certain we can be that our point estimate approximates the true mean of the population.

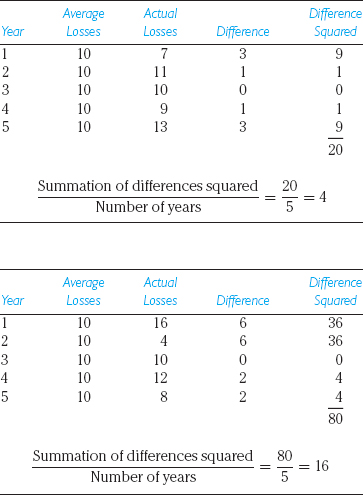

To illustrate this principle,1 let us assume an insurance company that has insured 1000 houses each year for the past five years examines its records and finds the following losses:

| Year | Houses That Burned |

| 1 | 7 |

| 2 | 11 |

| 3 | 10 |

| 4 | 9 |

| 5 | 13 |

Over the five-year period, a total of 50 houses burned, or an average of 10 houses per year. Since the number of houses insured each year was 1000, we estimate the chance of loss to be 1/100 or .01. In so doing, we are saying, “The average number of losses in our sample was 10 houses per 1000. If the mean of our sample approximates the mean of the entire population (all houses), the probability of loss is .01, and we predict that 10 houses will burn the sixth year if 1000 houses are again insured.” But we cannot be certain we are correct in our estimate of the probability. The mean of our sample (our estimate of the probability) may not be the same as the mean of the universe (the true probability). In other words, a possibility exists that the population mean is, say, 8 houses burning per year, but we are observing an average of 10 houses for those particular years. The confidence we can place in our estimate of the probability will vary with the dispersion or variation in the values that make up the mean of the sample. Compare this second set of losses with the preceding set:

| Year | Houses That Burned |

| 1 | 16 |

| 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 10 |

| 4 | 12 |

| 5 | 8 |

The total number of losses over the five-year period is again 50, and the average or mean of the losses is again 10 per year. However, there is a much greater variation in the number of losses from year to year. Even though the mean is the same in both groups, we would expect the mean of the first set of data to correspond more closely to the mean of the population. The greater the variation in the data on which our estimate of the probability is based, the greater we expect to be the variation between our estimate of the probability and the true probability. Since there is a relationship between the variation in the values that make up the sample mean and the likelihood that the sample mean approximates the population mean, it is useful to be able to measure the variation in these values.

Measures of Dispersion and Probability Estimate Statisticians have developed a number of measures of the dispersion in a group of values. For example, in the case of the first set of losses (7, 11, 10, 9, and 13), the number of losses in any given year varied from 7 to 13; in the second set of losses (16, 4, 10, 12, and 8), the number of losses varied from 4 to 16. This variation from the smallest number to the largest number is called the range, which is the simplest of the measures of dispersion. Another measure is the variance, which is computed by squaring the annual deviations of the values from the mean and taking an average of these squared differences. For example, the variance of the two sets of losses under discussion here would be computed as follows:

The variance of the first set of losses is 4, and that of the second set is 16. The larger variance of the second set is an indication of the greater variation in the data that compose the mean.

The square root of the variance is called the standard deviation, which is the most widely used and perhaps the most useful of all measures of dispersion. Since the variance of the first group of losses is 4, the standard deviation of that group is 2. In the case of the second set, where the variance is 16, the standard deviation is 4. Like the variance, the standard deviation is a number that measures the concentration of the values about their mean. The smaller the standard deviation relative to the mean, the less the dispersion and the more uniform the values. To return to the question of the accuracy of our point estimate of the probability based on the sample mean, the standard deviation is particularly useful in making estimates concerning the probable accuracy of this point estimate. In a sample with a lower standard deviation, we can be more confident in our estimate of the population mean.

Even if we know with certainty, however, that the population mean is 10 houses burning, that does not mean that 10 houses will burn. In a normal distribution, 68.27 percent of the cases will fall within the range of the mean plus or minus one standard deviation. The mean plus or minus two standard deviations will describe the range within which 95.45 percent of the cases will lie, and the range of three standard deviations above and below the mean will include 99.73 percent of the values in the distribution. Using the sample mean as our point estimate of the probability, we can estimate the probability that the number of houses burning next year will be within a certain range of the sample mean provided that we know the standard deviation of the distribution. In the case of the first set of losses, where the standard deviation was calculated to be 2, there is a 68.27 percent probability that the number of houses burning next year will be between 8 and 12 (i.e., 10 ± 2), a 95.45 percent probability that the number burning will be between 6 and 14 [10 ± (2 × 2)], and a 99.73 percent probability that the number will be between 4 and 16 [10 ± (3 × 2)]. In the case of the second set of data, where the values were more dispersed and the standard deviation was calculated to be 4, there is a 68.27 percent probability that the number burning will be between 6 and 14, a 95.45 percent probability that it will be between 2 and 18, and a 99.73 percent probability that it will be between 0 and 22.

What does all this mean? It means that uncertainty is inherent in our predictions. During the past five years, the average number of losses per 1000 dwellings has been 10, and on the basis of our estimate of the probability, we might predict 10 losses if 1000 houses are insured the sixth year, but we cannot be certain that our estimate of the probability is correct. Even if our estimate of the probability is correct, a different number of houses may burn next year. In fact, in the case of our first sample, our computations indicate that at best we can be 99 percent certain only that the true probability lies somewhere in the range of 4 to 16 losses per 1000 houses. The number of houses that may be expected to burn next year, other things being equal, is between 4 and 16. This means that results may be expected to deviate by as much as 6 from the predicted 10. This represents a possible deviation of 60 percent (6/10) from the expected values.2

Other things being equal, the larger our sample, the more closely we will expect the mean of the sample to coincide with the mean of the population and the smaller will be the margin we must allow for error. This is a consequence of the fact (which can be demonstrated mathematically) that the standard deviation of a distribution is inversely proportional to the square root of the number of items in the sample. For example, let us assume that we are able to increase the number of houses in our sample from 1000 to 100,000 per year and that we observe a 100-fold increase in losses.3 The average number of losses observed per year will increase from 10 to 1000. The standard deviation will also have increased, but, and this is the critical point, it will not have increased proportionately, for the standard deviation increases only by the square root of the increase in the size of the sample. Thus, the standard deviation, which is calculated to be 2 at the 1000 exposure level, will increase to 20 at the level of 100,000 houses. The new mean is 1000, and the mean plus or minus three standard deviations is now 1000 ± 60 and not 1000 ± 600. We can predict 1000 losses next year if 100,000 houses are insured, and we can feel 99 percent confident that the expected number of losses will fall somewhere between 940 and 1,060. This represents a potential deviation of only 6 percent (![]() ) from the expected value. The area of uncertainty has decreased because the size of the sample has increased. In our example, neither the probability nor our estimate of it has changed. The number of losses expected per 1000 houses is the same, but we are more confident that our estimate approximates the true probability.

) from the expected value. The area of uncertainty has decreased because the size of the sample has increased. In our example, neither the probability nor our estimate of it has changed. The number of losses expected per 1000 houses is the same, but we are more confident that our estimate approximates the true probability.

Dual Application of the Law of Large Numbers Based on the preceding discussion, it should be apparent that the law of large numbers is important in insurance for two reasons. First, a large sample will improve our estimate of the underlying probability. Even when we have estimated the probability on the basis of the sample of 100,000 houses per year, we cannot expect the narrower range of possible deviation if our estimate is applied to 1000 houses. As we have seen, even in the case of a priori probabilities where the probability is known, it must be applied to a large number of trials if we expect actual results to approximate the true probability. Therefore, in the case of empirical probabilities, the requirement of a large number has a dual application:

- To estimate the underlying probability accurately, the insurance company must have a sufficiently large sample. The larger the sample, the more accurate will be the estimate of the probability.

- Once the estimate of the probability has been made, it must be applied to a sufficiently large number of exposure units to permit the underlying probability to work itself out.

In this sense, to the insurance company, the law of large numbers means that the larger the number of cases examined in the sampling process, the better the chance of making a good estimate of the probability; the larger the number of exposure units to which the estimate is applied, the better the chance that actual experience will approximate a good estimate of the probability.

In making predictions on the basis of historical data, the insurance company implicitly says, “If things continue to happen in the future as they have happened in the past and if our estimate of what has happened in the past is accurate, this is what we may expect.” But things may not happen in the future as they have in the past. In fact, it is likely that the probability involved is constantly changing. In addition, we may have a poor estimate of the probability. All of this means that things may not turn out as expected. Since the insurance company bases its rates on its expectation of future losses, it must be concerned with the extent to which actual experience is likely to deviate from predicted results. For the insurance company, risk (or the possibility of financial loss) is measured by the potential deviation of actual from predicted results, and the accuracy of prediction is enhanced when the predictions are based on and are applied to a large number of exposure units. If the insurance company's actuaries, or statisticians, could be certain that their predictions would be 100 percent accurate, there would be no possibility of loss for the insurance company because premium income would always be sufficient to pay losses and expenses. Insofar as actual events may differ from predictions, risk exists for the insurer. To the extent that accuracy in prediction is attained, risk is reduced.

As a final point, although probability theory plays an important role in the operation of the insurance mechanism, insurance does not always depend on probabilities and predictions. Insurance arrangements can exist in which the participants agree to share losses and to determine each party's share of the costs on a post-loss basis. It is only when insurance is to be operated on an advance premium basis, with the participants paying their share of losses in advance, that probability theory and predictions are important.

![]()

Insurance Defined from the Viewpoint of Society

In addition to eliminating risk for the individual through transfer, the insurance device reduces the aggregate amount of risk in the economy by substituting certain costs for uncertain losses. These costs are assessed on the basis of the predictions made through the use of the law of large numbers. We may now formulate a second definition of insurance:

From the social point of view, insurance is an economic device for reducing and eliminating risk through the process of combining a sufficient number of homogeneous exposures into a group to make the losses predictable for the group as a whole.

Insurance does not prevent losses,4 nor does it reduce the cost of losses to the economy as a whole. In fact, it may have the opposite effect of causing losses and increasing the cost of losses for the economy as a whole. The existence of insurance encourages some losses for the purpose of defrauding the insurer, and, people are less careful and may exert less effort to prevent losses than they might if the insurance did not exist. Also, the economy incurs certain additional costs in the operation of the insurance mechanism. It must bear the cost of the losses and the additional expense of distributing the losses on some equitable basis.

![]()

Insurance: Transfer or Pooling?

The two definitions of insurance—from the viewpoint of the individual and from the viewpoint of society—reflect two different views of insurance, views that have divided insurance scholars for at least the past half century. The first view is that insurance is a device through which the individual substitutes a small certain cost for a large uncertain loss, and it emphasizes the transfer of risk. It does not attempt to explain how the risk is handled by the transferee. The second view is that insurance is a device for reducing and eliminating risk through pooling, and it emphasizes the role of insurance in reducing risk in the aggregate, which it does by pooling. Some writers maintain that the essential requisite in the insurance mechanism is the transfer of risk, while others argue that it is the pooling or sharing of risks.

Adherents of the “transfer” school point out that there are numerous examples of what are clearly insurance transactions, in which risks that are transferred to insurers are not pooled. There seems to be general agreement on the point that insurance involves the transfer of risk. Even in risk-sharing mechanisms, such as post-loss assessment plans, risk is transferred from the individual to the group. Those who emphasize pooling of risk point out that it is this feature of insurance that distinguishes insurance from other risk transfer techniques. Although they admit that pooling itself involves risk transfer (from the individual to the group), it is the pooling or combination of risks that constitutes the mechanism of insurance.

The definition of insurance from the perspective of the individual, as a device for the transfer of risk and the substitution of a small certain cost for a large uncertain loss, seems to be the better definition. It applies to all mechanisms we would call insurance, and it applies only to them. Since the pooling definition does not apply to all mechanisms that are considered insurance, it is somewhat less satisfactory. The essential feature of insurance is risk transfer. Pooling is an important technique available to the transferee, but it is not a requisite. Insurance transactions can occur in which the risk that is transferred is unique and in which there is no pooling. Although insurance generally involves the reduction of risk in the aggregate, which is achieved by pooling, insurance transactions need not involve pooling.

Actually, both definitions are useful. The definition of insurance from the individual's perspective defines the essence of insurance, based on its essential component, transfer. The definition of insurance from the perspective of society is a functional definition and explains how insurance usually achieves the transfer function.

![]()

Insurance and Gambling

Perhaps we should make one final distinction regarding the nature of insurance. It is often claimed that insurance is a form of gambling. “You bet that you will die and the insurance company bets that you won't” or “I bet the insurance company $300 against $100,000 that my house will burn.” The fallacy of these statements should be obvious. In the case of a wager, there is no chance of loss, hence no risk, before the wager. In the case of insurance, the chance of loss exists whether or not there is an insurance contract in effect. In other words, the basic distinction between insurance and gambling is that gambling creates a risk, while insurance provides for the transfer of an existing risk.

![]()

THE ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION OF INSURANCE

![]()

Property that is destroyed by an insured contingency is not replaced through the existence of an insurance contract. True, the funds from the insurance company may be used to replace the property, but when a house or building burns, society has lost a want-satisfying good. Insurance as an economic device is justified because it creates certainty about the financial burden of losses and because it spreads the losses that do occur. In providing a mechanism through which losses can be shared and uncertainty reduced, insurance brings peace of mind to society's members and makes costs more certain.

Insurance also provides for a more optimal utilization of capital. Without the possibility of insurance, individuals and businesses would have to maintain large reserve funds to meet the risks that they must assume. These funds would be in the form of idle cash or would be invested in safe, liquid, and low interest-bearing securities. This would be an inefficient use of capital. When the risk is transferred to the professional risk bearer, the deviations from expected results are minimized. As a consequence, insurers are obligated to keep much smaller reserves than would be the case if insurance did not exist. The released funds are then available for investment in more productive pursuits, resulting in a much greater productivity of capital.

![]()

ELEMENTS OF AN INSURABLE RISK

![]()

Although it is theoretically possible to insure all possibilities of loss, some are uninsurable at a reasonable price. For practical reasons, insurers are not willing to accept all the risks that others may wish to transfer to them. To be considered a proper subject for insurance, certain characteristics should be present. The four prerequisites listed next represent the “ideal” elements of an insurable risk. Although it is desirable that the risk have these characteristics, it is possible for certain risks that do not have them to be insured.

- There must be a sufficiently large number of homogeneous exposure units to make the losses reasonably predictable. Insurance, as we have seen, is based on the operation of the law of large numbers. A large number of exposure units enhances the operation of an insurance plan by making estimates of future losses more accurate.5

- The loss produced by the risk must be definite and measurable. It must be a type of loss that is relatively difficult to counterfeit, and it must be capable of financial measurement. In other words, we must be able to tell when a loss has taken place, and we must be able to set some value on the extent of it.

- The loss must be fortuitous or accidental. The loss must be the result of a contingency; that is, it must be something that may or may not happen. It must not be something that is certain to happen. If the insurance company knows that an event is inevitable, it also knows that it must collect a premium equal to the certain loss that it must pay, plus an additional amount for the expenses of administering the operation. Depreciation, which is a certainty, cannot be insured; it is provided for through a sinking fund. Furthermore, the loss should be beyond the control of the insured. The law of large numbers is useful in making predictions only if we can reasonably assume that future occurrences will approximate past experience. Since we assume that past experience was a result of chance happening, the predictions concerning the future will be valid only if future happenings are a result of chance.

- The loss must not be catastrophic. It must be unlikely to produce loss to a large percentage of the exposure units at the same time. The insurance principle is based on a notion of sharing losses, and inherent in this idea is the assumption that only a small percentage of the group will suffer loss at any one time. Damage that results from enemy attack would be catastrophic in nature. Additional perils, such as floods, would not affect everyone in the society but would affect only those who had purchased insurance. The principle of randomness in selection is closely related to the requirement that the loss must not be catastrophic.

![]()

Randomness

The future experience of the group to which we apply our predictions will approximate the experience of the group on which the predictions are based only if both have approximately the same characteristics. There must be a proportion of good and bad risks in the first group equal to the proportion of good and bad risks in the group on which the prediction is made. Yet human nature acts to interfere with the randomness necessary to permit random composition of the current group. The losses that are predicted are based on the average experience of the older group, but some individuals always are, and who realize they are, worse than average risks. Because the chance of loss for these risks is greater than that for the other members of society, they have a tendency to desire insurance coverage to a greater extent than the remainder of the group. This tendency results in what is known as adverse selection. Adverse selection is the tendency of the persons whose exposure to loss is higher than average to purchase or continue insurance to a greater extent than those whose exposure is less than average. Unless some provision is made to prevent adverse selection, predictions based on past experience will be useless in foretelling future experience. Adverse selection works in the direction of accumulating bad risks. Given that the predictions of future losses are based on the average loss of the past (in which good and poor exposures were involved), future losses will be worse than those of the past if the experience of the future is based on the experience of a larger proportion of bad risks. Therefore, the predictions will be invalid.

Adverse selection long caused private insurers to avoid the field of flood insurance. The adverse selection inherent in insuring fixed properties against the peril of flood is obvious. Only those individuals who feel that they are exposed to loss by flood are interested in flood insurance, and yet in the event of a flood, the likelihood is that all these individuals will suffer loss. The element of the sharing of the losses of a few by the many who suffered no loss would not exist. Although some insurers have written coverage against flood on fixed properties, the coverage has generally been unavailable from private insurers for those who need it most.6

The “war-risk exclusion” that life insurance companies insert in their contracts during wartime is another example of the adverse selection principle. On the basis of past experience, it has been shown that deaths from combat have not been catastrophic, yet it is precisely because the insurance companies prevented adverse selection that they have not been. The war-risk exclusion is put into policies during wartime to prevent soldiers who would not otherwise have purchased insurance from doing so when they are exposed to a greater chance of loss. Policies that are sold before the war begins and do not have the war-risk exclusion cover deaths that result from war. If the policies purchased during the war were based on the same randomness as those sold in peacetime, the war-risk exclusion would not be necessary, but in the absence of such a provision, the randomness would not exist and the company would be selected against.

![]()

Economic Feasibility

Sometimes, an additional attribute is listed as a requirement of an insurable risk: The cost of the insurance must not be high in relation to the possible loss, or the insurance must be economically feasible. We can hardly call this a requirement of an insurable risk since the principle is widely violated in the insurance industry today. The four elements of an insurable risk are characteristics of certain risks that permit the successful operation of the insurance principle. If a given risk lacks one of these elements, the operation of the insurance mechanism is impeded. The principle of “economically feasible insurability” is not really an impediment to the operation of the insurance principle but rather a violation of the principles of risk management and common sense.

![]()

SELF-INSURANCE

![]()

The term self-insurance has become a well-established part of the terminology of the insurance field despite disagreement as to whether such a mechanism is possible.7 From a purely semantic point of view, the term self-insurance represents a definitional impossibility. The insurance mechanism consists of the transfer of risk or pooling of exposure units, and since one cannot pool with or transfer to himself or herself, it can be argued that self-insurance is impossible. However, the term is widely used, and we ought to establish an acceptable operational definition, semantically incorrect though it may be.

Under some circumstances, it is possible for a business firm or other organization to engage in the same types of activities as a commercial insurer dealing with its own risks. When these activities involve the operation of the law of large numbers and predictions regarding future losses, they are commonly referred to as “self-insurance.”8 To be operationally dependable, such programs must possess the following characteristics:

- The organization should be big enough to permit the combination of a sufficiently large number of exposure units so as to make losses predictable. The program must be based on the operation of the law of large numbers.

- The plan must be financially dependable. In most cases, this will require the accumulation of funds to meet losses that occur, with a sufficient accumulation to safeguard against unexpected deviations from predicted losses.

- The individual units exposed to loss must be distributed geographically in such a manner as to prevent a catastrophe. A loss affecting enough units to result in severe financial loss should be impossible.

Apart from its semantic shortcomings, self-insurance is an overworked term. Few companies or organizations are large enough to engage in a sound program meeting the requirements outlined here. In the majority of cases, risks are retained without attempting to make estimates of future losses. In many cases, no fund is maintained to pay for losses. Furthermore, until the fund reaches the size adequate to pay the largest loss possible, the possibility of loss is not eliminated for the individual exposure units.

![]()

THE FIELDS OF INSURANCE

![]()

Insurance is a broad, generic term, embracing the entire array of institutions that deal with risk through the device of sharing and transfer of risks. Insurance may be divided and subdivided into classifications based on the perils insured against or the fundamental nature of the particular program. Basically, the primary distinction is between private insurance and social insurance. In addition to these two classes, we will examine a third class of quasi-social insurance coverages called public benefit guarantee programs.

Private insurance consists mostly of voluntary insurance programs available to the individual as a means of protection against the possibility of loss. This voluntary insurance is usually provided by private firms, but in some instances, it is offered by the government. The distinguishing characteristics of private insurance are that it is usually voluntary and that the transfer of risk is normally accomplished by means of a contract. Social insurance, in contrast, is compulsory insurance, usually operated by the government, whose benefits are determined by law and in which the primary emphasis is on social adequacy. In general, the benefits under social insurance programs attempt to redistribute income based on some notion of “social adequacy.” The largest of the social insurance programs in the United States is the Social Security system.

Unfortunately, there is no single criterion that can be used to distinguish private insurance from social insurance. Further complicating the situation, the designations private and voluntary are slightly misleading: Some “private insurance” is sold by the government, and not all compulsory insurance is social insurance. The following discussion of the fields of private insurance and social insurance will serve to distinguish them and will provide a basic introduction to the types of insurance to be discussed in later chapters.

![]()

Private (Voluntary) Insurance

As noted, private insurance consists of those insurance programs that are available to the individual as protection against financial loss. It is usually (but not always) voluntary, and generally (but not always) based on the concept of individual equity. Some private insurance coverages are compulsory, and although the emphasis is on individual equity, private insurance for some classes of insureds is subsidized by government or by other insureds. Furthermore, although most private insurance is sold by private firms, in a number of instances, it is offered by the government.9

Today, private insurance in the United States may be classified into three broad categories:

- Life insurance

- Health insurance

- Property and liability insurance

Life Insurance Life insurance is designed to provide protection against two distinct risks: premature death and longevity.10 As a matter of personal preference, death at any age is probably premature, and longevity (living too long) does not normally strike one as an undesirable contingency. From a practical point of view, however, a person can, and sometimes does, die before adequate preparation has been made for the future financial requirements of dependents. In the same way, a person can, and often does, outlive income-earning ability. Life insurance, endowments, and annuities protect the individual and his or her dependents against the undesirable financial consequences of premature death and longevity.

Health Insurance Accident and health insurance (or, more simply, health insurance) is defined as “insurance against loss by sickness or accidental bodily injury.”11 The “loss” may be the loss of wages caused by the sickness or accident, or it may be expenses for doctor bills, hospital bills, medicine, or the expenses of long-term care. Included within this definition are forms of insurance that provide lump-sum or periodic payments in the event of loss occasioned by sickness or accident, such as disability income insurance and accidental death and dismemberment insurance.

Property and Liability Insurance Property and liability insurance consists of those forms of insurance designed to protect against losses resulting from damage to or loss of property and losses arising from legal liability.12 It includes the following types of insurance:

Property insurance, sometimes referred to as fire insurance, is designed to indemnify the insured for loss of, or damage to, buildings, furniture, fixtures, or other personal property as a result of fire, lightning, windstorm, hail, explosion, and a long list of other perils. Originally, fire was the only peril insured against, but the number of perils insured against has gradually been expanded over the years. Today, two basic approaches are taken with respect to the perils for which coverage is provided. Under the first approach, called named-peril coverage, the specific perils against which protection is provided are listed in the policy, and coverage applies only for damage arising out of the listed perils. Under the second approach, called open-peril coverage, the policy lists the perils for which coverage is not provided, and loss from any peril not excluded is covered.13 Coverage may be provided for direct loss (i.e., the actual loss represented by the destruction of the asset) and for indirect loss (i.e., the loss of income and/or the extra expense that is the result of the loss of the use of the asset protected).

Marine insurance, like fire insurance, is designed to protect against financial loss resulting from damage to owned property except that here the perils are primarily those associated with transportation. Marine insurance is divided into two classifications: ocean marine and inland marine.

Ocean marine insurance policies provide coverage on all types of oceangoing vessels and their cargoes. Policies are also written to cover the shipowner's liability. Originally, ocean marine policies covered cargo only after it was loaded onto the ship. Today, the policies are usually endorsed to provide coverage from “warehouse to warehouse,” thus protecting against overland transportation hazards as well as those on the ocean.

Inland marine insurance seems like a contradiction in terms. The field developed as an outgrowth of ocean marine insurance and “warehouse- to warehouse” coverage. Originally, inland marine insurance developed to cover goods being transported by carriers such as railroads, motor vehicles, or ships and barges on the inland waterways and in coastal trade. It was expanded to cover instrumentalities of transportation and communication, such as bridges, tunnels, pipelines, power transmission lines, and radio and television communication equipment. Eventually, it was expanded to include coverage on various types of property not in the course of transportation but that is away from the owner's premises.

Automobile insurance provides protection against several types of losses. First, it protects against loss resulting from legal liability arising out of the ownership or use of an automobile. In addition, the medical payments section of the automobile policy consists of a special form of health and accident insurance that provides for the payment of medical expenses incurred as a result of automobile accidents. Coverage is provided against loss resulting from theft of the automobile or damage to it from many different causes.

Liability insurance embraces a wide range of coverages. The form with which most students are familiar is automobile liability insurance, but there are other liability hazards as well. Coverage is available to protect against nonautomobile liability exposures such as ownership of property, manufacturing and construction operations, the sale or distribution of products, and many other exposures.

Workers compensation insurance had its beginning (in the United States) shortly after the turn of the century when the various states began to pass workers compensation laws. Under these laws, the employer was made liable for injuries to workers that arose out of and in the course of their employment. Workers compensation insurance provides for the payment of the obligation these statutes impose on the employer.14

Equipment breakdown insurance (also referred to as boiler and machinery insurance) was introduced in the late 1800s to cover the explosion hazard inherent in early boilers. It was later expanded to include coverage for accidental breakdown of a wide range of types of equipment. More recently, with advances in automation, it was further expanded to include coverage for nearly all types of equipment. To prevent losses, equipment breakdown insurers maintain an extensive inspection service, and this service is a primary reason for the purchase of the coverage. Although the contract does not require them to do so, the insurers make periodic inspections of the objects insured. As a result, losses are reduced and the insured benefits.

Burglary, robbery, and theft insurance protect the property of the insured against loss resulting from criminal acts of others. Because a standard clause in these crime policies excludes acts by employees of the insured, they are referred to as “nonemployee crime coverages.” Protection against criminal acts by employees is provided under fidelity bonds, which are discussed shortly.

Cybersecurity Insurance or cyber insurance protects against losses from a variety of cyber-related incidents, including data breaches, losses due to computer viruses, and cyber extortion. Data and technology-related losses are frequently excluded from other property and liability insurance policies, and coverage is provided by specialized policies.

Credit or trade credit insurance is a specialized form of coverage (available to manufacturers and wholesalers) that indemnifies the insured for losses resulting from their inability to collect from customers. The coverage is written subject to a deductible based on the normal bad-debt loss and with a provision requiring the insured to share a part of each loss with the insurer.

Title insurance is another narrowly specialized form of coverage.15 Basically, it provides protection against financial loss resulting from a defect in an insured title. The legal aspects of land transfer are rather technical, and the possibility always exists that the title may be unclear. Under a title insurance policy, the insurer agrees to indemnify the insured to the extent of any financial loss suffered as a result of the transfer of a defective title. In a sense, title insurance is unique in that it insures against the effects of some past event rather than against financial loss resulting from a future occurrence.

Fidelity and Surety Bonds Fidelity and surety bonds represent a special class of risk transfer device, and opinions differ as to whether bonds should be classified as insurance. In fact, certain fundamental differences exist between a bond and an insurance policy, and strictly speaking, it can be argued that some bonds are not contracts of insurance. In general terms, a bond is an agreement by one party, the surety, to answer to a third person, called the obligee, for the debt or default of another party, called the principal. In other words, the surety guarantees a certain type of conduct on the part of the principal, and if the principal fails to behave in the manner guaranteed, the surety will be responsible to the obligee.

Bonding is divided into two classes: fidelity bonds and surety bonds. Fidelity bonds protect the obligee against dishonesty on the part of his or her employees and are commonly called employee dishonesty insurance. In most respects, they resemble insurance more closely than surety bonds do, and many authorities consider them a form of casualty insurance.

Most surety bonds are issued for persons doing contract construction, those connected with court actions, and those seeking licenses and permits. Basically, the surety bond guarantees that the principal is honest and has the necessary ability and financial capacity to carry out the obligation for which he or she is bonded. The surety obligates itself with the principal to the obligee in much the same manner that the cosigner of a note assumes an obligation with a borrower to a lender. The primary obligation to perform rests with the principal, but if the principal is unable to meet the commitment after exhausting all his or her resources, the surety must provide funds to pay for the loss. In this event, the surety may take possession of the principal's assets and convert them into cash to reimburse itself for the loss paid.

Although there is a difference of opinion as to whether bonds are insurance, insurance regulators normally include them within the framework of the contracts they regulate. Furthermore, property and liability insurers sell these bonds, and suretyship is normally considered a part of the property and liability insurance business.

![]()

Social Insurance

Social insurance differs from private insurance in a number of respects. In the case of social insurance, we use the insurance mechanism for transferring and sharing risk, but we do so on a somewhat qualified basis. Social insurance provides compulsory protection for personal risks, that is those that involve the possible loss of income or assets because of premature death, dependent old age, sickness or disability, or unemployment. Social insurance seeks to provide a “floor of protection” to persons who would not individually be able to cope with certain fundamental risks. It does this by providing benefits not only to those in need but to others as well.

Modern social insurance originated in Germany in the 1880s under chancellor Otto von Bismarck. During the period 1884 through 1889, Germany constructed a model social insurance program composed of three elements. The first was sickness insurance for practically all employed persons, a nineteenth-century universal health insurance program. The second element was accident insurance, for work-related injuries, in effect, the first workers compensation program. The final element in the program was insurance for invalidity and old age, the equivalent of our Social Security system.16 From Germany, the idea of social insurance spread to other European nations and eventually to the United States.17

In the United States, the first social insurance program was the workers compensation system, which was adopted by the individual states during the early 1900s. A quarter of a century later, the Social Security Act of 1935 established the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program, better known as the Social Security system.

Social Insurance Defined Any definition of social insurance must, by its very nature, be complex. The following definition of social insurance has been proposed:18

Social insurance is a device for the pooling of risks by their transfer to an organization, usually governmental, that is required by law to provide pecuniary or service benefits to or on behalf of covered persons upon the occurrence of certain predesignated losses under all the following conditions:

- Coverage is compulsory by law in virtually all instances.

- Eligibility for benefits is derived, in fact or in effect, from contributions having been made to the program by or in respect of the claimant or the person as to whom the claimant is dependent: there is no requirement that the individual demonstrate inadequate financial resources, although a dependency status may need to be established.

- The method of determining benefits is prescribed by law.

- The benefits for any individual are not directly related to contributions made by or in respect to him or her but instead usually redistribute income so as to favor certain groups such as those with low former wages or large numbers of dependents.

- There is a definite plan for financing the benefits that is designed to be adequate in terms of long-range considerations.

- The cost is borne primarily by contributions that are usually made by covered persons, their employers, or both.

- The plan is administered or at least supervised by the government.

- The plan is not established by the government solely for its present or former employees.

Certain elements in the definition require clarification. First, because a specific type of insurance is compulsory does not make it a social insurance program. Compulsory automobile insurance, for example, does not meet other conditions listed and, therefore, is not social insurance. Furthermore, although the government is usually the transferor in a social insurance plan, this is not a prerequisite. Workers compensation insurance is a social insurance coverage that is sold by commercial insurers.

The second of the conditions listed in the definition distinguishes social insurance from public assistance or welfare programs, in which eligibility for benefits is based on need. Because of the contributions made by or on behalf of the insureds under a social insurance program, the right to benefits is essentially a statutory right and is not based on a “need” or a “means test.”

More than any of the others, the fourth element in the definition distinguishes social insurance from private insurance. In private insurance, insurers attempt to distribute the loss costs equitably, in proportion to the loss-producing characteristics of the insureds. It would be considered inequitable, for example, to charge a 25-year-old person the same premium for life insurance as that charged to a 65-year-old person. In social insurance, individual equity is secondary in importance to the social adequacy of the benefits. Benefits are weighted in favor of certain groups so all persons will be provided a minimum floor of protection. In the federal Social Security program, for example, the benefits are weighted in favor of the low-income groups, and persons with large families. Although benefits under social insurance programs are not directly proportional to contributions, they are at least loosely related to the earnings of the individual. Therefore, even though social adequacy rather than individual equity is stressed, there is at least a loose relationship between earnings and benefits.

The fifth condition, that there be a definite plan for financing the benefits that is designed to satisfy long-range considerations, merely requires that there be some sort of long-range planning. It does not demand that the obligations under the program be fully funded. In private insurance, insurers are required to maintain reserves to fund the future obligations they will incur. In social insurance, the future obligations are rarely funded in full but depend on the future taxing power of the government.

The sixth principle is known as the self-supporting contributory principle. This means that the costs are not financed from the general revenues of the U.S. Treasury but are paid for primarily by those who expect to benefit from the programs. In most instances the support is derived from contributions by employees, employers, and the self-employed. This method of financing is unique to U.S. social insurance programs because, in most other countries with extensive programs, a part of or all the financing comes from general government revenues.

Social Insurance Programs in the United States Social insurance developed later in the United States than in European countries, but social insurance programs exist at the national and state levels. The principal social insurance programs under federal jurisdiction include the OASDI program and the Medicare program, both administered by the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Railroad Retirement, Railroad Disability, and Railroad Unemployment insurance programs, administered by the Railroad Retirement Board. Social insurance programs under state jurisdiction include workers compensation, unemployment compensation, and compulsory temporary disability insurance laws.

Workers Compensation The first social insurance legislation in the United States was workers compensation laws, enacted by the individual states beginning in 1908. Workers compensation provides benefits to workers and their dependents when a worker suffers an occupational injury or disease. Workers compensation laws replaced a system of employers' liability, under which injured workers could recover for occupational injuries only through a lawsuit against the employer. Although workers compensation insurance is considered a form of social insurance, it is sold by private insurers and by state workers compensation funds. In addition, because workers compensation laws impose liability on the employer for program benefits, it is a form of private insurance from the employers' perspective.

Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance The Social Security Act of 1935 stands as the most comprehensive piece of social legislation of its kind in the history of this country. It established the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Program (OASDI), better known as Social Security, the largest of all government insurance programs in the United States.

Initially, the law provided only retirement benefits. It was modified to provide survivor benefits in 1939. Disability benefits were added in 1956, and in 1965, it was further expanded by the addition of the Medicare program. As presently constituted, the program provides life insurance, disability insurance, and retirement pensions to those covered under the program, which includes nearly all gainfully employed persons in the nation and their dependents. The only exceptions are certain government employees who are covered under a civil service retirement system, railroad employees (protected under their own programs), and some persons engaged in irregular employment. By the end of 2012, about 57 million people were receiving monthly benefits under all the OASDI programs. Total revenues for the programs amounted to $840 billion, and expenditures totaled $786 billion.19

Railroad Retirement, Disability, and Unemployment Programs Another U.S. government agency, the Railroad Retirement Board, administers and serves as the fiduciary for a comprehensive program of retirement pensions, survivor benefits, unemployment insurance, and disability coverage for persons employed by the railroads. In addition to having unique status with respect to retirement benefits, railroad workers are covered under a separate unemployment compensation law, which includes coverage for occupational and nonoccupational disabilities as well as unemployment not connected with a disability.

Unemployment Insurance The Social Security Act of 1935 also initiated our system of unemployment compensation. Although some states had enacted unemployment laws, most states were reluctant to enact such programs because they feared that their industries would suffer a competitive disadvantage with other states unfettered by this kind of legislation. The Social Security Act used the power of the federal government to levy taxes to induce the several states to enact unemployment insurance plans. The Social Security Act of 1935 imposed a tax of 1 percent on the total payroll of most employers who had eight or more employees but provided that employers would be permitted to offset 90 percent of the tax through credit for taxes paid to a state unemployment insurance program meeting standards specified in the law. In effect, this meant that any state that did not enact a qualified unemployment compensation law would suffer a financial drain. Not surprisingly, all the states elected to set up such programs and qualified for the tax offset. The tax has been altered several times since 1935.

Medicare The federal government's Medicare program, which is a basic part of the Social Security system, became effective on July 1, 1966. The program provides health insurance to nearly all citizens over 65 and to certain disabled persons. The first coverage, designated Part A, is compulsory hospitalization insurance, financed by payroll taxes levied on employers and employees. Part B is voluntary medical insurance, designated to help pay for physicians' services and other medical expenses not covered by Part A. Part D, Prescription Drug Coverage, was created by the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 and became available on January 1, 2006. Parts B and D are financed by monthly premiums shared by participants and the federal government. Medicare covered 50.7 million people in 2012 and had expenditures of $574.2 billion.20

State Compulsory Temporary Disability Funds In addition to workers compensation and unemployment compensation, six jurisdictions (California, Hawaii, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Puerto Rico) have enacted compulsory temporary disability laws that require insurance coverage against loss of income from nonoccupational disabilities. These programs furnish a compulsory complement to the workers compensation laws, which cover occupational disabilities. In addition to requiring participation in the program and prescribing benefit levels, all the states act as insurers. In Rhode Island, the state operates a monopolistic insurance program, while in the other jurisdictions state funds compete with private insurers providing the coverage.21

Is Social Insurance Really Insurance? One more aspect of social insurance, often expressed as a criticism, should at least be mentioned at this juncture: the question of whether social insurance is really insurance or whether it is a unique method of providing benefits without the use of the basic principles of insurance. Despite the rather substantial differences between the operational features of social and private insurance, it is our conclusion that the basic principles of insurance are as applicable in one as in the other. As explained earlier, insurance is the mechanism by which the risk of financial loss is transferred by individuals (to a professional transferee or to a group) and loss costs are distributed in some equitable manner among the members of the group. Since social insurance uses risk transfer and loss sharing, it is “insurance.” Critics who disagree with this conclusion maintain that social insurance programs are “actuarially unsound” and, therefore, cannot be insurance. The effectiveness of such an argument must, of course, depend on the definition of “actuarial soundness.” To the critics, an insurance program is actuarially sound only if it is possible to measure the probability of loss with a high degree of accuracy and only if proper reserves are maintained to provide for future obligations. If this high degree of precision in measuring probabilities does not exist, according to the argument, and if appropriate reserves are not maintained, the program should not be called insurance. For example, the OASDI program is affected by so many variables (such as, population growth, the aging of the population, inflation, politics, and the like) that a precise prediction of long-range future obligations is impossible. Therefore, these critics assume that the OASDI program is actuarially unsound and so is not insurance.

It is true, perhaps, that the success of the insurance principle must depend on the ability to obtain at least a reasonable approximation of the probability of loss. However, a precise prediction is unnecessary. There are many forms of private insurance, such as windstorm, hail, earthquake, and even automobile, in which precise statistical calculations of probabilities are impossible. In some cases, probability calculations are nothing more than enlightened guesses. To the extent that a reasonable approximation of loss can be obtained, these types of private insurance are actuarially sound. To the extent that the future obligations under social insurance programs are capable of approximation for a reasonable time in the future, they are actuarially sound. Actuarial soundness demands a prediction of future obligations and has nothing to do with the maintenance of reserves. Therefore, an insurance program can be actuarially sound whether the future obligations are funded or not, just as long as there is sufficient income to pay for the obligations. The partial funding of many of our social insurance programs does not remove these from the category of insurance.

![]()

Public Guarantee Insurance Programs

In addition to the private insurance and social insurance coverages we have discussed, some insurance programs do not fit precisely into either field. This third class of insurance programs consists of government-operated, compulsory, quasi-social insurance programs, mainly in connection with financial institutions holding assets belonging to the public. We have designated these “public guarantee insurance programs.” The best known of these programs is the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which insures depositors against loss resulting from failure of commercial banks.

Under these public guarantee insurance programs, government-funded agencies use the insurance principle to provide protection to lenders, depositors, or investors against loss arising from the collapse of a financial institution holding deposits of the public or of some other type of fiduciary. Usually, as in the case of the FDIC, the insurance is closely allied with the function of regulation.22

Federal Public Guarantee Insurance Programs Public guarantee insurance programs operate at the state and federal level. There are four major federal public guarantee insurance programs.

The FDIC The modern prototype for this form of insurance, the FDIC, is a public corporation created by the federal government in 1933 to insure deposits in banks and thereby protect depositors against loss in case of bank failure. The FDIC currently insures accounts of any one depositor at any one bank up to $250,000.23 This provides protection against loss of the depositor's funds as a result of failure or insolvency of the bank. Because the FDIC provides separate coverage for funds in different ownership categories (e.g., single owner accounts, joint accounts, qualified retirement accounts), an individual may be eligible for more than $250,000 in coverage at a single bank. The FDIC was originally funded by an appropriation from general government revenues. Its income is now derived from assessments on the deposits of the banks covered. Although the FDIC has served successfully as a guarantor of depositors for over half a century, another federal instrumentality, the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC), ended in 1989 in the face of massive savings and loan failures.24

The National Credit Union Administration Another organization, the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) provides deposit insurance for members of credit unions. Like the FDIC, the NCUA affords protection up to $250,000 per depositor. The NCUA derives its income from annual assessments on covered deposits.

Securities Investor Protection Corporation Comparable applications of this type of public insurer have been made in other fields. For example, following the failure of a large national securities brokerage firm with consequent losses to its clients, the federal government established an insurer designed to protect investors dealing with licensed security brokerage firms in case such firms did fold. The Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC), established in 1970, provides custodial account protection for those investors who allow their brokers to keep their securities for safety and trading convenience. All registered brokers must insure under the program, which protects each investor up to $500,000, including up to $250,000 for cash. Although SIPC's primary role is to protect investors if the brokerage firm becomes insolvent, SIPC will cover losses from unauthorized trading in a customer's securities accounts. Coverage is not provided for market risk, which is the risk that the market value of the securities will decline.

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) was created as a part of the far-reaching legislation known as the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). It provides insurance guaranteeing employees covered by private pension plans that they will receive their vested benefits up to a specified maximum if the plan is terminated. The PBGC and plan termination insurance are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 23.

State Public Guarantee Insurance Programs Public guarantee insurance programs exist at the state level. For example, some states maintain state funds similar to the FDIC to insure the deposits of state mutual savings banks. In addition, the following guarantee programs fit into this category.

State Insurer Insolvency Funds All states have funds designed to protect insurance policyholders from losses in the event their insurer becomes insolvent. Most of these funds operate on a post-loss assessment basis, meaning the surviving insurers are assessed after an insolvency to pay the losses of the insolvent insurer. New York operates a pre-loss assessment fund for property and liability insurers. These funds are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 6.

Unsatisfied Judgment Funds Five states (Maryland, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, and North Dakota) have established unsatisfied judgment funds that provide for payment to persons injured in automobile accidents when the negligent party is unable to pay for the damages. The financing of these funds varies among the states. In North Dakota, the fund is financed by a uniform levy on each registered motor vehicle. In Maryland and New Jersey, a fee is levied on each registered motor vehicle, but the amount is higher for uninsured drivers than for those who carry insurance. In addition, Maryland levies a tax of ½ percent on all auto premiums written by insurance companies in the state.

Public Guarantee Programs as Insurance Despite occasional debates over whether these programs are insurance, all utilize the basic insurance mechanisms of pooling and transfer of risk. Those who argue that the term insurance is misapplied to these plans point out that there is some question as to whether the individual programs meet the desirable elements of an insurable risk as discussed in Chapter 2. For example, in some instances, it is doubtful whether the risks are fortuitous. Furthermore, an element of catastrophe arises out of the dynamic nature of the credit exposure. Nevertheless, the programs all exhibit the basic characteristics of insurance, including the transfer of risk from the individual to a group and the sharing on some equitable basis of losses that do occur.

![]()

Similarities in the Various Fields of Insurance

As we have seen in this chapter, the term insurance encompasses a wide variety of approaches used by society for sharing risks. While attempting to distinguish among the various classes of insurance, we have focused on the differences. In closing, we should note some of the similarities, lest the emphasis on differences obscure the common elements.