CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Describe the evolution of modern risk management and identify the developments that led to the transition from insurance management to risk management

- Define and explain what is meant by the term risk management

- Identify the various reporting relationships that the risk management function may assume in an organization

- Identify the two broad approaches to dealing with risk that are recognized by modern risk management theory

- Identify the four techniques that are used in managing risk

- Describe risk management's contribution to the organization

- Distinguish risk management from insurance management and general management

Risk management is a scientific approach to the problem of risk that has as its objective the reduction and elimination of risks facing the business firm. Risk management evolved from the field of corporate insurance buying and is recognized as a distinct and important function for all businesses and organizations. Many business firms have highly trained individuals who specialize in dealing with pure risk. In some cases, this is a full-time job for one person or for an entire department within the company. Those who are responsible for the entire program of pure risk management (of which insurance buying is only a part) are risk managers. Although the term risk management is a recent phenomenon, the practice of risk management is as old as civilization itself. In the broad sense of the term, risk management is the process of protecting one's person and assets. In the narrower sense, it is a managerial function of business that uses a scientific approach to dealing with risks. As such, it is based on a specific philosophy and follows a well-defined sequence of steps. In this chapter, we will examine the distinguishing features of risk management.

![]()

THE HISTORY OF MODERN RISK MANAGEMENT

![]()

Although the term risk management may have been used in the special sense in which it was used here earlier, the general trend in its current usage began in the early 1950s. One of the earliest references to the concept of risk management in literature appeared in the Harvard Business Review in 1956.1. In that article, the author proposed what, for the time, seemed a revolutionary idea: that someone within the organization should be responsible for “managing” the organization's pure risks. At the time that the term risk manager was suggested, many large corporations had a staff position referred to as the “Insurance Manager.” This was an apt title since, in most cases, the position entailed procuring, maintaining, and paying for a portfolio of insurance policies obtained for the benefit of the company. The earliest insurance managers were employed by the first of the giant corporations, the railroads and steel companies, which hired them as early as the turn of the century. As the capital investment in other industries grew, insurance came to be a more and more significant item in the budget of firms. Gradually, the insurance buying function was assigned as a specific responsibility to in-house specialists.

Although risk management has its roots in corporate insurance buying, the transition from insurance buying to risk management was not an inevitable evolutionary process. The emergence of risk management was a revolution that signaled a dramatic shift in philosophy. It occurred when the attitude toward insurance changed and insurance lost its traditional status as the standard approach for dealing with a corporation's risk. For the insurance manager, insurance had always been the standard accepted approach to dealing with risks. Although insurance management included techniques other than insurance (such as noninsurance or retention and loss prevention and control), these techniques had always been considered primarily as supplements to insurance.

The preeminence of insurance as a method for dealing with pure risks by corporate insurance buyers is probably understandable. Many of the earliest insurance buyers were skilled insurance technicians, often hired from an insurance agency or brokerage firm. They understood the principles of insurance and applied their knowledge to obtain the best coverage for the premium dollars spent. Traditional insurance textbooks had always preached against the dollar-trading practices that characterized some lines of insurance, and most insurance buyers knew economies could be achieved through the judicial use of deductibles. Despite these precursors of the risk management philosophy, the notion persisted that insurance was the preferred approach for dealing with risk. When insurance was generally agreed to be the standard approach to dealing with pure risks, the decision not to insure was courageous indeed. If an uninsured loss occurred, the risk manager would surely have been criticized for the decision not to insure. The problem was that not much consideration was given to whether insurance was the most appropriate solution to the organization's risk. The insurance managers' function was to buy insurance and they could hardly be criticized for doing so. After all, that was their job.

What caused the change in attitude toward insurance and the shift to the risk management philosophy? Although there is room for disagreement, it can be argued that the risk management philosophy had to wait for the development and growth of decision theory, with its emphasis on cost-benefit analysis, expected value, and the other tools of scientific decision making.

Whether it was an accident of timing or cause and effect, the risk management movement in the business community coincided with a revision of curriculum in business colleges throughout the United States. During the 1950s, two studies of the curriculum of business colleges were published in the United States: the Gordon and Howells Report and the Pierson Report.2 Both studies concluded with stinging criticisms of the curriculum at U.S. business colleges, arguing that it was outdated and did not help prepare students for their future role as decision makers. Although some business faculty took issue with the conclusions of these reports, business schools began to change their curricula, adding new courses and changing the focus of others. The most significant changes in the curriculum were the introduction of operations research and management science, with a shift in focus from descriptive courses to normative decision theory.3 Whereas previous courses described how and why people chose among options, prescriptive decision theory was introduced to focus on how choices should be made. Not surprisingly, insurance faculty were among the first business academics to embrace decision theory. Many were trained in actuarial science, the mathematical underpinning of insurance. As the earliest quantitative specialists in business schools, they were knowledgeable in the methodologies of decision theory. Equally important, they had an inventory of interesting questions to which these tools could be applied in business situations, questions involving the choices among the techniques that could be used to address risk. Academics not only began to question the central role that had always been assigned to insurance, they also developed the theoretical justification for the challenge.

Simultaneously and independently, system engineers in the military and in the aerospace industry were developing new approaches to loss prevention and control that came collectively to be referred to as systems safety. Systems safety evolved in response to increasingly complex problems that needed to be solved and for which traditional approaches were inadequate. The initial stimulus for systems safety was the creation of the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) system, which served as the key element in the nation's cold war strategy of deterrence through the threat of nuclear retaliation. Later, systems safety was applied to the U.S. space program.

As the title indicates, systems safety views a process, a situation, a problem, a machine, or any other entity as a system rather than as a process, situation, problem, or machine. An accident occurs when a human or a mechanical component of a system fails to function when it should. The objective of systems safety is to identify these failures and eliminate them or minimize their effects. Systems safety rejects the notion that accidents are a matter of chance, meaning something that simply happens. Instead, accidents are created events, enabled to happen by choices or decisions. Viewed from this perspective, accidents are not an inevitable part of the workplace, not acts of God, or simply unlucky breaks. If the causes of accidents can be identified, they can be eliminated, and accidents can be prevented.4

As time passed, the influence of the changes in business college curriculum and systems safety began to spread through the insurance-buying community. Some corporate insurance buyers came to realize there might be more cost-efficient ways of dealing with risk. It occurred to them that perhaps the most effective approach would be to prevent losses from happening in the first place and to minimize the economic consequences of the losses they were unable to prevent. Thus evolved the notion that management, having identified and evaluated the risks to which it is exposed, can plan to avoid the occurrence of certain losses and minimize the impact of others. This led to the conclusion that the cost of risk can be managed and held to the lowest levels possible.

The risk management philosophy made sense, and it spread from organization to organization. When the insurance buyers' professional association decided to change its name to the Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS) in 1975, the change signaled a transition that was well under way. The Risk and Insurance Management Society publishes a magazine called Risk Management, and the Insurance Division of the American Management Association publishes a wide range of reports and studies to assist risk managers. In addition, the Insurance Institute of America developed an education program in risk management with a series of examinations leading to a diploma in risk management. The curriculum for this program was revised in 1973, and a professional designation, Associate in Risk Management (ARM), was instituted.

As it exists today, risk management represents the merging of three specialties: decision theory, risk financing, and risk control. Decision theory has its roots in operations research and management science. The risk financing specialty came from the disciplines of finance and insurance, and the risk control specialty represents the merger of traditional safety management and loss prevention, as developed by the insurance industry, and systems safety emerged from the military and aerospace industry.

![]()

ENTERPRISE RISK MANAGEMENT

![]()

Traditionally, the risk management function was focused on the pure risks facing a business. More recently, interest has grown in a concept known as enterprise risk management, which attempts to integrate the management of all of the firm's pure and speculative risks. Each firm uses a slightly different categorization scheme, reflecting the key risks for its business, but the following risks are typically highlighted in an enterprise risk management program.

Market risk is the risk arising from adverse movements in market prices. Market risk includes changes in the price of commodities (such as those required for production) and changes in equity prices, interest rates, and foreign exchange rates.

Credit risk is the risk arising from the potential that a borrower will fail to pay a debt.

Liquidity risk is the risk that the business will have insufficient liquid assets to meet obligations that come due.

Operational risk has no universally accepted definition. It is most commonly defined as the risk of loss from inadequate or failed internal processes, people, or systems or from external events.5 The operational risk category is intended to include risks such as fraud, breaches in internal controls, technology risks (e.g., programming errors or failures in IT systems), and external events such as earthquakes, floods, and war. It encompasses the pure risks identified in Chapter 1 (personal risks, property risks, liability risks, and risk arising from failure of others).6 However, operational risk is broader, also encompassing failed internal controls leading to credit, market, or other losses.7

Other risks frequently identified in an enterprise risk management program include the following:

- Reputational risk: the potential that negative publicity will cause a loss

- Strategic risk: the risk of failing to successfully implement the firm's strategies

- Compliance risk: the risk of failing to comply with laws and regulations.

The term financial risk is often used to refer to market risk, credit risk, and liquidity risk, because these have traditionally been the responsibility of the firm's corporate financial officer or treasurer. Similarly, the term financial risk management is often used to refer to the management of these risks.

Much of the interest in enterprise risk management is driven by a desire to better manage the ways in which a firm's capital is used. As firms seek to enter new business lines or expand in a given business line, it is not enough to know that the expected return is high. The return must be sufficiently high to compensate the firm for the risk. Enterprise risk management, then, seeks to identify the risks facing the firm, to quantify those risks, and to manage the risks efficiently consistent with the firm's strategic objectives. The holy grail for enterprise risk management is a single firmwide measure of risk that can be used to allocate capital and evaluate the performance of business units.

To date, however, a single firmwide measure of risk has largely been elusive. Much of risk management continues to be done in “silos,” with financial risk managers focusing on financial risks, and traditional risk managers focusing on pure risks. To some extent, this is not surprising. While there is some overlap, there remain differences in the techniques used to deal with pure and speculative risks. The expertise required to manage interest rate and foreign exchange risks different from the expertise required for managing pure risks. Although some risk managers have the expertise to deal in the arena of hedging, futures, options, and derivatives, others feel sufficiently challenged by their existing responsibilities.

While interest in enterprise risk management is growing, its full potential has yet to be realized.8 The greatest progress in enterprise risk management has been in financial institutions, particularly banks and insurance companies. Given the nature of these businesses, financial risk management is critical. Regulators and rating agencies have encouraged the development of enterprise risk management for these businesses.

What remains unclear is who will have ultimate responsibility for managing a company's enterprise risk portfolio. The disagreement is not about whether financial risks should be managed but whether they should be managed by the same person who manages the risks of fire, explosions, embezzlements, and legal liability. Nor is there disagreement about the necessity of someone managing the organization's total risk portfolio. The dispute is over whether this overall management of enterprise risk should be done by the risk manager (perhaps by creating the position of chief risk officer, as some firms have done). Skeptics argue that there is an authority with the overall responsibility for managing enterprise risk: the chief executive officer (CEO).

The remainder of this text takes a narrower view of risk management and focuses on traditional risk management, which is the management of pure risks, insurable and uninsurable. Many of the principles of risk management discussed in this chapter are equally applicable to traditional and enterprise risk management.

![]()

RISK MANAGEMENT DEFINED

![]()

As a relatively new discipline, risk management has been defined in a variety of ways by different writers and users of the term. Although they vary in detail, most definitions stress two points: risk management is concerned with risk and it is a process or function that involves managing those risks. We propose the following definition of risk management.

Risk management is a scientific approach to dealing with risks by anticipating possible losses and designing and implementing procedures that minimize the occurrence of loss or the financial impact of the losses that do occur.

Note first that risk management is described as a “scientific approach” to the problem of risk. Although risk management seeks to proceed in a scientific manner, it must be admitted that risk management is not a science in the same sense as the physical sciences are, anymore than management is a science. As the term is generally understood, a science is a body of knowledge based on laws and principles that can be used to predict outcomes. Scientists seek to discover and test these laws through laboratory experiments aimed at uncovering the principles that govern or control the events being studied. The standard method of physical sciences, for example, is the controlled experiment, but risk managers cannot use this method. Instead, risk management derives its rules (laws) from the general knowledge of experience, through deduction, and from precepts drawn from other disciplines, particularly decision theory. Although risk management is not a science, it uses a scientific approach to the problem of managing risk. This scientific approach that distinguishes risk management from earlier approaches to risk decisions can be illustrated by contrasting it with those earlier approaches.

Humans have always found ways to deal with risks and have reacted to adversity in a variety of ways. At the personal level, the natural instinct for self-preservation dictates an instinctive reaction to danger and hazards. Like most creatures, we react automatically to danger, taking whatever measures are available to avoid injury or loss. These instinctive reactions to risk situations are not decisions but the innate self-preservation instinct.

In addition to our instinctive reactions to danger, much of what one might classify as personal risk management is a learned behavior. “Don't play with matches,” “Don't tease the dog,” “Don't run with scissors” are all axioms of risk management that are instilled in the individual from an early age.

Individuals acquire a body of principles that dictate patterns of action that are designed to protect and preserve. They become innate standards for behavior that, while sometimes violated, represent rules for personal loss prevention and control.

Another part of human behavior in responding to risk is institutionalized. Many insurance- buying decisions are dictated by legal, contractual, or societal conventions. The youthful driver does not really want to buy automobile insurance. He or she wants to drive a car. Most states require that if you drive, you must have insurance. Similarly, while there are probably some consumers who must decide whether to purchase homeowners insurance, for the overwhelming majority, there is little choice. Unless the individual can purchase the home for cash, there will be a mortgage, and the lender will insist on insurance. In short, many risk management and insurance decisions at the personal level are dictated by convention.

Often, the same institutional, legal, and societal pressures dictate risk management and insurance decisions in the business world. Business managers have found themselves responsible for the management of a firm's risks without any notion of how to go about the process. Bewildered by the confusing array of insurance coverages available, many business managers turn the problem of what to buy over to an outside party, such as an insurance agent. More often than not, the decision to delegate the management of risk to an outside party is based on the misperception that insurance buying involves complicated decisions that the business manager is incapable of making. And because the agent does not want to be in a defensive position when a loss occurs, he or she recommends more rather than less insurance. The result is often dissatisfaction on the part of the buyer over “the high cost of insurance.” Risk management, which approaches the decisions related to risk scientifically, is a solution to the challenges in dealing with risk. In fact, the distinguishing feature of risk management is the way in which it approaches the decision-making process. Risk management seeks to make the “best” decision about how to deal with a particular risk. In Chapter 4, we will see how this is done.

![]()

RISK MANAGEMENT TOOLS

![]()

Our definition of risk management states that it deals with risk by designing and implementing procedures that minimize the occurrence of loss or the financial impact of the losses that do occur. This indicates the two broad techniques that are used in risk management for dealing with risks. In the terminology of modern risk management, the techniques for dealing with risk are grouped into two broad approaches: risk control and risk financing. Risk control focuses on minimizing the risk of loss to which the firm is exposed and includes the techniques of avoidance and reduction. Risk financing concentrates on arranging the availability of funds to meet losses arising from the risks that remain after the application of risk control techniques and includes the tools of retention and transfer.

![]()

Risk Control

Broadly defined, risk control consists of those techniques that are designed to minimize, at the least possible costs, those risks to which the organization is exposed. Risk control methods include risk avoidance and the various approaches at reducing risk through loss prevention and control efforts.

Risk Avoidance Technically, avoidance takes place when decisions are made that prevent a risk from even coming into existence. Risks are avoided when the organization refuses to accept the risk, even for an instant. The classic example of risk avoidance by a business firm is a decision not to manufacture a particularly dangerous product because of the inherent risk. Given the potential for liability claims that may result if a consumer is injured by a product, some firms judge that the risk is not worth the potential gain.

Risk avoidance should be used in those instances in which the exposure has catastrophic potential and the risk cannot be reduced or transferred. Generally, these conditions will exist in the case of risks for which the frequency and the severity are high and neither can be reduced.

Although avoidance is the only alternative for dealing with some risks, it is a negative rather than a positive approach. Personal advancement of the individual and progress in the economy require risk taking. If avoidance is used extensively, the firm may not be able to achieve its primary objectives. A manufacturer cannot avoid the risk of product liability by avoiding the risk and still stay in business. For this reason, avoidance is, in a sense, the last resort in dealing with risk. It is used when there is no other alternative.

Risk Reduction Risk reduction consists of all techniques that are designed to reduce the likelihood of loss or the potential severity of those losses that do occur. It is common to distinguish between those efforts aimed at preventing losses from occurring and those aimed at minimizing the severity of loss if it should occur, referring to them respectively as loss prevention and loss control. As the designation implies, the emphasis of loss prevention is on preventing the occurrence of loss; that is, on controlling the frequency. Prohibition against smoking in areas where flammables are present is a loss prevention measure. Similarly, measures to decrease the number of employee injuries by installing protective devices around machinery are aimed at reducing the frequency of loss. Other risk reduction techniques focus on lessening the severity of those losses that occur, such as the installation of sprinkler systems. These are loss control measures. Other methods of controlling severity include segregation or dispersion of assets and salvage efforts. Dispersion of assets will not reduce the number of fires or explosions that may occur, but it can limit the potential severity of the losses that do occur. Salvage operations after a loss has occurred can minimize the resulting costs of the loss.

Another distinction is sometimes made between the “engineering approach” to loss prevention and control, in which the principal emphasis is on the removal of hazards that may cause accidents, and the “human behavior approach,” in which the elimination of unsafe acts is stressed. This distinction is based on the focus of control measures and represents two schools of thought regarding the emphasis in loss prevention and control. The human behavior approach is based on the view that since most accidents result from human failure, the most effective approach to loss prevention is to change people's behavior. The engineering approach, in contrast, emphasizes systems analysis and mechanical design, aimed at protecting people from careless acts that are viewed as perhaps inevitable. National Safety Council ads on television and in print media urging drivers not to drink typify the human behavior approach. Air bags in automobiles, which are activated without human intervention, typify the engineering approach.

A final way of classifying risk reduction measures is by the timing of their application, which may be prior to the loss event, at the time of the event, or after the loss event. Safety inspections and drivers' training classes illustrate measures that are designed to prevent the occurrence before losses occur. Seat belts and air bags are designed to minimize the amount of damage at the time an accident occurs. Post-event loss prevention measures related to auto accidents include negotiating with injured persons for an out-of-court settlement or a stern defense in litigation.

![]()

Risk Financing

Risk financing, in contrast with risk control, consists of those techniques that focus on arrangements designed to guarantee the availability of funds to meet those losses that do occur. Fundamentally, risk financing takes the form of retention or transfer. All risks that cannot be avoided or reduced must, by definition, be transferred or retained. Frequently, transfer and retention are used in combination for a particular risk, with a portion of the risk retained and a part transferred.

Risk Retention Risk retention is perhaps the most common method of dealing with risk.9 Individuals, like organizations, face an almost unlimited number of risks; in most cases, nothing is done about them. Risk retention may be conscious or unconscious (i.e., intentional or unintentional). Because risk retention is the “residual” or “default” risk management technique, any exposures that are not avoided, reduced, or transferred are retained. This means that when nothing is done about a particular exposure, the risk is retained. Unintentional (unconscious) retention occurs when a risk is not recognized. The individual or organization unwittingly and unintentionally retains the risk of loss arising out of the exposure. Unintentional retention can also occur in those instances in which the risk has been recognized but when the measures designed to deal with it are improperly implemented. If, for example, the risk manager recognizes the exposure to loss in connection with a particular exposure and intends to transfer that exposure through insurance but then acquires an insurance policy that does not fully cover the loss, the risk is retained.

Unintentional risk retention is always undesirable. Because the risk is not perceived, the risk manager is never afforded the opportunity to make the decision concerning what should be done about it on a rational basis. Also, when the unintentional retention occurs as a result of improper implementation of the technique that was designed to deal with the exposure, the resulting retention is contrary to the intent of the risk manager.

Risk retention may be voluntary or involuntary. Voluntary retention results from a decision to retain risk rather than to avoid or transfer it. Involuntary retention occurs when it is impossible to avoid, reduce, or transfer the exposure to an insurance company. Uninsurable exposures are an example of involuntary retention.

Some forms of voluntary retention occur by default. When an organization purchases insurance that inadequately covers the exposure, it retains the risk of loss for that part of the exposure that is inadequately insured. When a $5 million building is insured for $4 million, the organization retains a $1 million risk of loss. Similarly, in the case of liability insurance, an organization retains the risk of loss in excess of the limits of coverage that it carries. A business that carries a $5 million umbrella, for example, tacitly assumes the risk of all losses in excess of this limit. Although the risk manager may not explicitly consider the decision in this context, selecting the $5 million limit is a decision to retain risks in excess of that limit.

A final distinction that may be drawn is between funded retention and unfunded retention. In a funded retention program, the firm earmarks assets and holds them in some liquid or semiliquid form against the possible losses that are retained. The need for segregated assets to fund the retention program will depend on the firm's cash flow and the size of the losses that may result from the retained exposure.

The form that risk retention may assume varies widely. Retention may be accompanied by specific budgetary allocations to meet uninsured losses and may involve the accumulation of a fund to meet deviations from expected losses. On the other hand, retention may be less formal, without any form of specific funding. A larger firm may use a loss-sensitive rating program (in which the premium varies directly with losses), various forms of self-insured retention plans, or even a captive insurer. The small organization uses deductibles, noninsurance, and various other forms of retention techniques. The specific programs may differ, but the approach is the same.

Risk Transfer Transfer may be accomplished in a variety of ways. The purchase of insurance contracts is, of course, a primary approach to risk transfer. In consideration of a specific payment (the premium) by one party, the second party contracts to indemnify the first party up to a certain limit for the specified loss that may or may not occur.

Another example of risk transfer is the process of hedging, in which an individual guards against the risk of price changes in one asset by buying or selling another asset whose price changes in an offsetting direction. For example, futures markets have been created to allow farmers to protect themselves against changes in the price of their crop between planting and harvesting. A farmer sells a futures contract, which is a promise to deliver at a fixed price in the future. If the value of the farmer's crop declines, the value of the farmer's future position goes up to offset the loss.10

Risk transfer may take the form of contractual arrangements such as hold-harmless agreements, in which one individual assumes another's possibility of loss.11 For example, a tenant may agree under the terms of a lease to pay any judgments against the landlord that arise out of the use of the premises. Risk transfer may involve subcontracting certain activities, or it may take the form of surety bonds.12

![]()

RISK MANAGEMENT AS A BUSINESS FUNCTION

![]()

As noted earlier, risk management is a merger of the disciplines of decision theory, finance, insurance theory, and loss prevention and control specialties. Because risk management draws on these different disciplines, it is sometimes considered a subset of one of them. In many colleges and universities, insurance and risk management are a part of the finance curriculum, while in other schools, they are located in another department. In fact, the study of risk management is a separate and distinct discipline that draws on and integrates the knowledge from a variety of other business fields. The same ambiguity about the nature of risk management is reflected in the view of risk management within many organizations. In some organizations, it is viewed as a part of finance; in others, it may be considered part of the safety organizations. In the organization, as in the academic environment, risk management is a distinct and separate function of business.

The famous French management authority Henri Fayol, writing in 1916, divided all activities of industrial undertakings into six broad functions, including one (which Fayol called security) that is essentially equivalent to what we call risk management. The six broad functions into which Fayol divided industrial undertakings were technical activities (such as production and manufacturing), commercial activities (buying and selling), financial activities (finding sources of capital and managing capital flows), accounting activities (recording and analyzing financial information), managerial activities (organizing, planning, command, coordination, and control), and security activities (protecting the property and persons of the enterprise).13

While the other functions described by Fayol all developed as well-defined academic disciplines and became divisions in the corporate structure headed by a vice president, “security” somehow got lost in the shuffle, and it was not until the 1950s that Fayol's six-function division of business activities was resurrected.

Risk Management Distinguished from Insurance Management In addition to its relationship to general management, risk management should be distinguished from insurance management. Risk management is broader than insurance management, in that it deals with insurable and uninsurable risks and the choice of the appropriate techniques for dealing with these risks. Because risk management evolved from insurance management, the focus of some risk managers has been primarily with insurable risk. Properly, the focus should include all pure risk, insurable and uninsurable. In other words, the risk manager cannot ignore those pure risks that are not insurable. A good example is shoplifting losses. Although shoplifting losses represent a pure risk exposure, they are not generally insurable on an economical basis.

Risk management also differs from insurance management in philosophy. The insurance manager views insurance as the accepted norm or standard approach to dealing with risk, and retention is regarded as an exception to this standard. The insurance manager contemplates his or her insurance program and asks the following: “Are there any risks that I should retain?” “How much will I save in insurance costs if I retain them?” In viewing loss prevention measures, the insurance manager asks the following: “How much will this measure reduce my insurance costs?” “How long will it take for a new sprinkler system to pay for itself in reduced fire insurance premiums?” The risk manager, in contrast, views insurance as simply one of several approaches to dealing with pure risks. Rather than asking, “Which risks should I retain?”, the risk manager asks, “Which risks must I insure?”

The difference is one of emphasis. The insurance management philosophy views insurance as the accepted norm, and retention or noninsurance must be justified by a premium reduction that is, in some sense or another, “big enough.” Under the risk management philosophy, it is insurance that must be justified. Since the cost of insurance must generally exceed the average losses of those who are insured, the risk manager believes insurance is a last resort and should be used only when necessary.

Risk management, then, is something more than insurance management in that it deals with insurable and uninsurable risks, but it is something less than general management since it does not deal (except incidentally) with business risk.

![]()

Risk Management's Contribution to the Organization

Risk management can contribute to the organization's general goals in several ways. The first and most important one is in guaranteeing, insofar as possible, that the organization will not be prevented from pursuing its other goals as a result of losses associated with pure risks. If risk management made no contributions other than guaranteeing survival, this alone would seem to justify its existence. But risk management can contribute to corporate and organizational goals in other ways.

Risk management can contribute directly to profit by controlling the cost of risk for the organization, that is, by achieving the goal of economy. Since profits depend on the level of expenses relative to income, to the extent that risk management activities reduce expenses, they directly increase profits. Risk management activities can directly affect the level of costs in several ways. One, of course, is in the area of insurance buying. To the extent that the risk manager is able to achieve economies in the purchase of insurance, the reduced cost will increase profits. In choosing between transfer and retention, the risk manager will select the most cost-effective approach. This means that expenses for risk transfer will generally be lower in organizations in which the choice between transfer and retention considers the relative cost of each approach.

Risk management can reduce expenses through risk control measures. To the extent that the cost of loss prevention and control measures is less than the dollar amount of losses that are prevented, the expense of uninsured loss is reduced. In addition, since loss prevention and control measures can reduce the cost of insurance, risk control has a dual effect on expenses. Risk control measures that reduce the cost of losses include those measures that prevent losses from occurring as well as those that reduce the amount of loss when a loss does occur.

In addition to reducing expenses associated with losses, risk management can, in some instances, increase income. It can also be argued that when the pure risks facing an organization are minimized, through appropriate control and financing techniques, the firm has greater latitude in the speculative risks it can undertake. Although it is useful to distinguish between pure and speculative risks with respect to the manner in which they are addressed and the responsibility for dealing with them, there are inevitable trade-offs between pure and speculative risk in the overall risk portfolio of an organization. It has been argued that the total amount of risk that an organization faces is important, since firms with higher total risk are more likely to find themselves in financial distress than firms with lower total risk. When the organization faces significant pure risks that cannot be (or are not) reduced or transferred, its ability to bear speculative risk is reduced. By managing the amount of pure risk with which the organization must contend, risk management increases the firm's ability to engage in speculative risks.

Risk management can permit an organization to engage in activities that involve speculative risk by minimizing the pure risks associated with such ventures. Consider, for example, the organization contemplating an entry into international markets. This decision will create pure and speculative risks for that organization. If the combination of pure and speculative risks exceeds the risk threshold that management is willing to accept, the international venture may be abandoned. If, on the other hand, the risk manager can reduce the level of pure risk, the aggregate pure and speculative risk may be reduced to a level management finds acceptable. To illustrate, suppose the corporation's top management is considering setting up a subsidiary in a politically troubled country. The threat of expropriation may appear to be too great and might cause management to reject the opportunity in favor of a safer but less profitable alternative. However, if the risk manager reports that political risk insurance is available and reasonably priced, management may decide in favor of the opportunity and, thereby, generate increased revenue and profits. The risk manager, who theoretically is responsible for managing all pure risks and can choose from many alternative risk treatment methods, is in a position to contribute substantially to the operating results of the corporation.14

![]()

The Risk Manager's Job

The term risk manager can be used in a functional sense to mean anyone who performs the risk management job, regardless of whether that person is an employee of the organization, an outside consultant, or an agent or broker. As the term will be used here, however, it will refer to an individual employed by the organization who is responsible for the risk management function.

Even when viewed from this perspective, every organization has a risk manager. The individual may not recognize that he or she is performing the risk management function, but in every organization, someone must make decisions that relate to the pure risks facing the organization. In a large corporation, the risk manager is (or should be) a well-paid professional who has a specific title and job description that relates to the management of risks. In a small company, he or she may be the president or managing partner. In a moderate-sized company, the risk manager may be the chief financial officer or someone on an intermediate staff level.

The scope of the risk manager's job differs across organizations. In the broadest case, the risk manager has overall responsibility for all risk control and risk-financing activities, including the organization's employee benefit plan. Periodic surveys conducted by the Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS) reveal that the responsibility and duties of risk managers vary with the size of the organization. In some instances, the risk managers are responsible for the firm's employee benefit plans, while in other cases, their responsibility is limited to those risks that threaten the firm itself.

About one-fourth of risk managers reported having responsibility for some loss prevention activities within their organizations. A higher percentage reported more responsibility for safety and fire engineering, however, than for security, which seems to indicate some fragmentation in responsibility for loss prevention in organizations.

Position in the Organization In general, one usually finds risk managers in one of three corporate departments, depending on the history and development of risk management in the particular firm. In some organizations, the risk manager evolved from the insurance manager, who was traditionally located in the finance division or under the comptroller. In these companies, risk management is viewed as a financial function and reports to the finance department. In companies in which the risk manager evolved from the employee benefits manager, the risk manager may be in the personnel division. Finally, in some companies, the risk manager will have developed from the safety function. Here, the risk manager will generally be located in the division that traditionally housed the safety director, usually the production division.

Most risk managers have a financial orientation, reporting to a vice president–finance, treasurer, or comptroller, although there is a growing school of thought that says he or she should be in a less specialized department, reporting to an executive vice president or even to the president to illustrate the company-wide scope of risk management activities.

![]()

MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT RISK MANAGEMENT

![]()

Although risk management has become a popular topic of discussion, some of what is discussed reflects a misunderstanding of risk management. Some of these misconceptions reflect a misreading of the literature while others reflect defects in the literature. The first misconception is that the risk management concept is applicable principally to large organizations. The second is that the risk management approach to dealing with pure risks seeks to minimize the role of insurance.

![]()

Universal Applicability

If one were to judge on the basis of much of the literature dealing with the concept of risk management, it would be easy to conclude that risk management has no useful application except with respect to the problems facing a large industrial complex. This misconception can easily result from the fact that many of the techniques with which writers have been preoccupied (e.g., self-insurance plans and captive insurers) do apply primarily to giant organizations. Most of the articles on risk management have been written by practicing professional risk managers. It is natural that they would write about the techniques they use in their own companies, and nearly all professional risk managers are employed by large organizations. But the risk management philosophy and approach applies to organizations of all sizes (and to individuals as well) even though some of the more esoteric techniques may have limited application in the case of the average organization.

As the risk manager's position has grown within the corporate framework and risk management has become a recognized term in business jargon, the interest in risk management has increased in businesses of all sizes. The small firm cannot afford a full-time professional risk manager, yet the principles of risk management are as applicable to a small organization as to a giant international firm. As this text will illustrate, the principles of risk management are nothing more than common sense applied to the management of pure risks facing an individual or organization. The principles are applicable to organizations of all sizes, as well as to individuals and families. Although the techniques may differ in scope and complexity, the same risk management tools are used in either case.

![]()

Anti-Insurance Bias?

The second misconception about risk management is that it is anti-insurance in its orientation and seeks to minimize the role of insurance in dealing with risk. This misconception stems from risk management literature. Much of the literature on risk management has been preoccupied with topics related to risk retention, self-insurance programs, and captive insurance companies. Indeed, if one were to ask practitioners in the insurance field to describe the essence of risk management, meaning its philosophy, many would respond that the major thrust of risk management is on the retention of risk and on the use of deductibles. Although it is true that retention is an important technique for dealing with risks, this is not what concerns risk management.

The essence of risk management is not on the retention of exposures. Instead, it involves dealing with risks by whatever mechanism is most appropriate. In many instances, commercial insurance will be the only acceptable approach. Although the risk management philosophy suggests some risks should be retained, it also dictates some risks must be transferred. The primary focus of the risk manager should be on the identification of the risks that must be transferred to achieve the primary risk management objective. Only after this determination has been made does the question of which risks should be retained arise. More often than not, determining which risks should be transferred determines which risks will be retained, that is, the residual class that does not need to be transferred.

![]()

RISK MANAGEMENT AND THE INDIVIDUAL

![]()

Risk management evolved formally as a function of business. Insurance managers became risk managers, and with the transition certain principles of scientific insurance buying, which had always been used to some extent, were formalized. For the most part, these principles are commonsense applications of the cost-benefit principle, and they are equally applicable to the insurance buying decisions of the individual or the family unit. Like the business firm, the individual or family unit has a limited number of dollars that can be allocated toward the protection of assets and income against loss. Personal risk management is concerned with the allocation of these dollars in some optimal manner and makes use of the same techniques as does business risk management. To achieve maximum protection against static losses, the individual must select from among the risk management tools of retention, reduction, and transfer.

![]()

THE RISK MANAGEMENT PROCESS

![]()

The risk management process can be divided into a series of individual steps that must be accomplished in managing risks. Identifying these individual steps helps guarantee that important phases in the process will not be overlooked. Although it is useful for the purpose of analysis to discuss each of these steps separately, in practice, the steps tend to merge with one another. The six steps in the risk management process are the following:

- Determination of objectives

- Identification of risks

- Evaluation of risks

- Consideration of alternatives and selection of the risk treatment device

- Implementation of the decision

- Evaluation and review

![]()

Determination of Objectives

The first step in the risk management process is the determination of the objectives of the risk management program: deciding what the organization would like its risk management program to do. Despite its importance, determining the objectives of the program is the step in the risk management process that is most likely to be overlooked. As a consequence, the risk management efforts of many firms are fragmented and inconsistent. Many of the defects in risk management programs stem from an ambiguity regarding the objectives of the program.

Mehr and Hedges, in their classic Risk Management in the Business Enterprise, suggest that risk management has a variety of objectives, which they classify into two categories: pre-loss objectives and post-loss objectives, and suggest the following objectives in each category.15

| Post-Loss Objectives | Pre-Loss Objectives |

| Survival | Economy |

| Continuity of operations | Reduction in anxiety |

| Earning stability | Meeting externally imposed |

| Continued growth | Obligations |

| Social responsibility | Social responsibility |

Although all the pre-loss and post-loss objectives suggested by Mehr and Hedges have relevance in the risk management effort, multiple objectives such as these raise the following question: Which objective is primary?

Value Maximization Objectives One eminent scholar has argued that the ultimate goal of risk management is the same as the ultimate goal of the other functions in a business: to maximize the value of the organization.16 Modern financial theory suggests that this value that is to be maximized is reflected in the market value of the organization's common stock. According to this view, risk management decisions should be appraised against the standard of whether or not they contribute to value maximization. It is a view difficult to disagree with; it is also a view that is consistent with the objectives suggested by Mehr and Hedges. With limited exceptions, all the Mehr and Hedges objectives do, in one way or another, contribute to value maximization. Value maximization is the ultimate goal of the organization and is a reasonable standard for appraising corporate decisions in a consistent manner. It is also a logical objective for the individual or family. At the same time, the value maximization objective has some limitations for risk management. The most important is that it is relevant primarily to the business sector. For other organizations, such as nonprofit organizations and government bodies, value maximization is not particularly relevant.

The Primary Objective of Risk Management The first objective of risk management, like the first law of nature, is survival: to guarantee the continuing existence of the organization as an operating entity in the economy. The primary goal of risk management is not to contribute directly to the other goals of the organization, whatever they may be. Rather, it is to guarantee that the attainment of these other goals will not be prevented by losses that might arise out of pure risks. This means the most important objective is not to minimize costs or to contribute to the profit of the organization. Nor is it to comply with legal requirements or to meet some nebulous responsibility related to social responsibility of the firm. Risk management can and does do all these things, but they are not the principal reason for its existence. The main objective of risk management is to preserve the operating effectiveness of the organization. We propose the following primary objective for the risk management function:

The primary objective of risk management is to preserve the operating effectiveness of the organization, that is, to guarantee that the organization is not prevented from achieving its other objectives by the losses that might arise out of pure risk.

The risk management objective must reflect the uncertainty inherent in the risk management situation. Because one cannot know what losses will occur and what the amount of such losses will be, the arrangements made to guarantee survival in the event of loss must reflect the worst possible combination of outcomes. If a loss occurs and, as a result, the organization is prevented from pursuing its other objectives, then the risk management objective has not been achieved. While not immediately obvious, the risk management objective has not been achieved when there are unprotected loss exposures that could prevent the organization from pursuing its other objectives should the loss occur even if the loss does not occur. For this reason, the objective refers to losses that might arise out of pure risks. The question is not only whether the organization survives but whether it would have survived under a different combination of circumstances.

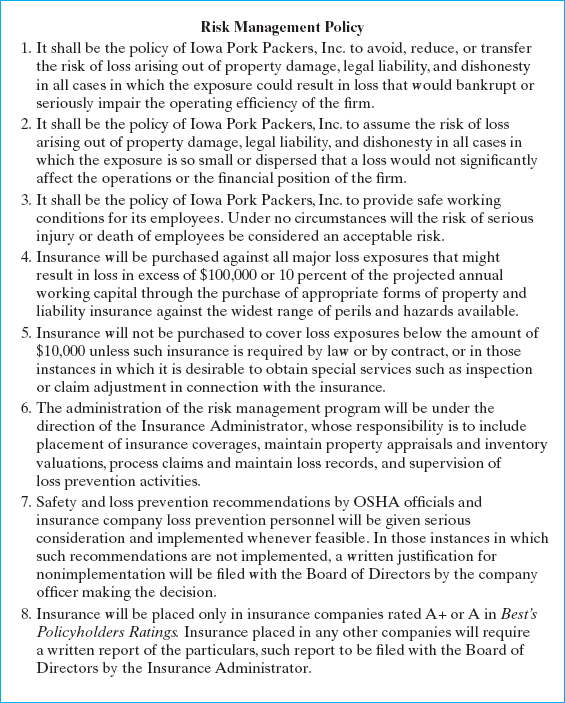

The Risk Management Policy Major policy decisions related to insurance should be made by the highest policy-making body in the organization, such as the board of directors, since these decisions are likely to involve large financial considerations, in terms of premiums paid over the long term or risks assumed if hazards are not insured. In addition, it is the board of directors and the professional managers of the firm who are responsible for the preservation of the organization's assets. Once the objectives have been identified, they should be formally recognized in a risk management policy. A formal risk management policy statement provides a basis for achieving a logical and consistent program by offering guidance for those responsible for programming and buying the firm's insurance. Figure 2.1 is a sample of a corporate risk management policy.

![]()

Identifying Risk Exposures

Obviously, before anything can be done about the risks an organization faces, someone must be aware of them. In one way or another, someone must dig into the operations of the company and discover the risks to which the firm is exposed. In one sense, risk identification is the most difficult step in the risk management process. It is difficult because it is a continual process and because it is nearly impossible to know when it has been done completely.

It is difficult to generalize about the risks that a given organization is likely to face because differences in operations and conditions give rise to differing risks. Some risks are relatively obvious while many can be and often are overlooked. To reduce the possibility of failure to discover important risks facing the firm, most risk managers use some systematic approach to the problem of risk identification.

FIGURE 2.1 Sample Risk Management Policy

Risk Identification Techniques The first step in risk identification is to gain as thorough a knowledge as possible of the organization and its operations. The risk manager needs a general knowledge of the goals and functions of the organization: what it does and where it does it. This knowledge can be gained through inspections, interviews with appropriate persons within and outside the organization, and an examination of internal records and documents.

Analysis of Documents The history of the organization and its current operations are contained in a variety of records. These records represent a basic source of information required for risk analysis and exposure identification. These documents include the organization's financial statements, leases and other contracts, asset schedules, inventory records, appraisals and valuation reports, buy-sell agreements, and countless other documents.

Analysis of the firm's financial statements, in particular, can aid in the process of risk identification. The asset listing in the balance sheet may alert the risk manager to the existence of assets that might otherwise be overlooked. The income and expense classification in the income statement may likewise indicate areas of operation of which the risk manager was unaware.17

Flowcharts Another tool that is useful in risk identification is a flowchart. A flowchart of an organization's internal operations views the firm as a processing unit and seeks to discover all the contingencies that could interrupt its processes. These might include damage to a strategic asset located in a bottleneck within the firm's operations or the loss of the services of a key individual or group through disability, death, or resignation. When extended to include the flow of goods and services to and from customers and suppliers, the flowchart approach to risk identification can highlight potential accidents that can disrupt the firm's activities and its profits.18

Internal Communication System To identify new risks, the risk manager needs a far-reaching information system that yields current information on new developments that may give rise to risk. Among the various activities that have relevance to the risk management function, some of the more important are new construction, remodeling, or renovation of the firm's properties, the introduction of new programs, products, activities, or operations, and other similar changes in the organization's activities.

Tools of Risk Identification Exposure identification is an essential phase of risk management and insurance management. Because insurance management is the older field, the technique of identifying insurable exposures was highly developed when the risk management movement began. Insurance companies created insurance policy checklists that identified the various risks for which they offered coverage. They also developed extensive application forms for various types of insurance that elicited information about hazards that needed to be reflected in rating and underwriting decisions. Although these tools focused on the perils and hazards against which insurers offered protection, they provided a base on which risk identification methods could be constructed. Many of the tools that had been used by insurance agents and insurance managers to identify insurable exposures were expanded and adapted to aid in the identification of other risks for which the risk manager is responsible.

A few of the more important tools used in risk identification include risk analysis questionnaires, exposure checklists, and insurance policy checklists. These, combined with a vivid imagination and a thorough understanding of the organization's operations, can help guarantee that important exposures are not overlooked.

Risk Analysis Questionnaires Risk analysis questionnaires, sometimes called fact finders, are designed to assist in identifying risks facing an organization. They do this by leading the user through a series of penetrating questions, the answers to which indicate hazards and conditions that give rise to risk. Originally, such questionnaires were generic and were intended for use by a wide range of businesses. As a result, they did not address unusual exposures or identify loss areas that might be unique to a given firm. Today, risk analysis questionnaires are available for a wide range of specific industries.

Exposure Checklists A second important aid in risk identification and one of the most common tools for risk analysis is a risk exposure checklist, which is a listing of common exposures. A checklist cannot include all possible exposures to which an organization may be subject; the nature and operations of different organizations vary too widely for that. However, it can be used effectively in conjunction with other risk identification tools as a final check to reduce the chance of overlooking a serious exposure.

Insurance Policy Checklists Insurance policy checklists are available from insurance companies and publishers specializing in insurance-related publications. Typically, such lists include a catalog of the various policies or types of insurance that a given business might need. The risk manager can consult this list, picking out those policies applicable to the firm. A principal defect in using insurance policy checklists for risk identification is that such checklists concentrate on insurable risks only, ignoring the uninsurable pure risks.19

Expert Systems With the advances in computer technology, many of the tools and techniques used in risk identification have been consolidated in computer software to create expert systems. An expert system used in risk identification incorporates the features of risk analysis questionnaires, exposure checklists, and insurance policy checklists in a single tool. The most sophisticated risk management expert systems include detailed, industry-specific risk questionnaires and exposure checklists. These survey questionnaires are detailed and assist in the identification of not only common exposures but those that may be unique to the specific industry.20

Combination Approach Required The preferred method of risk identification consists of a combination approach, in which all the tools previously listed are brought to bear on the problem. In a sense, each of these tools can provide a part to the puzzle, and combined, they can be of considerable assistance to the risk manager. But no individual approach or combination of these tools can replace the diligence and imagination of the risk manager in discovering the risks to which the firm is exposed.

![]()

Evaluating Risks

Once the risks have been identified, the risk manager must evaluate them. Evaluation implies some ranking in terms of importance, and ranking suggests measuring some aspect of the factors to be ranked. In the case of loss exposures, two facets must be considered: the possible severity of loss and the possible frequency or probability of loss. Evaluation involves measuring the potential size of the loss and the probability that the loss is likely to occur.

A Priority Ranking Based on Severity One of the techniques used by scientists and engineers in the U.S. space program was criticality analysis, which was an attempt to distinguish the important factors from the overwhelming mass of unimportant ones. Given the wide range of losses that can occur, from the minute to the catastrophic, it seems logical that exposures be ranked according to their criticality. Certain risks, because of the severity of the possible loss, will demand attention prior to others, and in most instances there will be a number of exposures that are equally demanding.

Any exposure that involves a loss that would represent a financial catastrophe ranks in the same category, and there is no distinction among risks in this class. It makes little difference if bankruptcy results from a liability loss, a flood, or an uninsured fire loss. The net effect is the same. Therefore, rather than ranking exposures in some order of importance, such as “1, 2, 3,” it is more appropriate to rank them into general classifications such as critical, important, and unimportant. One set of criteria that may be used in establishing such a priority ranking focuses on the financial impact that the loss would have on the firm, such as this example list:

- Critical risks include all exposures to loss in which the possible losses are of a magnitude that would result in bankruptcy.

- Important risks include those exposures in which the possible losses would not result in bankruptcy but would require the firm to borrow in order to continue operations.

- Unimportant risks include those exposures in which the possible losses could be met out of the existing assets or current income of the firm without imposing undue financial strain.

Assignment of individual exposures into one of these three categories requires determination of the amount of financial loss that might result from a given exposure as well as the ability of the firm to absorb such losses. Determining the ability to absorb the losses involves measuring the level of uninsured loss that could be borne without resorting to credit and determining the maximum credit capacity of the firm.21

The Loss Unit Concept One of the most relevant measures of severity, which unfortunately has not been widely discussed, is the loss unit. The loss unit is the total of all financial losses that could result from a single event, taking into consideration the various exposures. It includes the loss for direct damage to property, the loss of income, and the liabilities that could result from a single occurrence. Computing the loss unit requires calculation of the maximum possible loss for each of these exposures and then aggregating the totals. The significance of the loss unit is that while an organization might be able to retain certain of the exposures individually, there is no guarantee that losses will occur individually. The loss unit is an attempt to alert management to the potential catastrophe that could result under the worst possible conditions.

Probability and Priority Rankings Although the potential severity is the most important factor in ranking exposures, an estimate of the probability may be useful in differentiating among exposures with relatively equal potential severity. Other things being equal, exposures characterized by high frequency should receive attention before exposures with low loss frequency. Exposures that exhibit a high loss frequency are often susceptible to improvement through risk control measures. Having some notion of the loss frequency for different exposures can help determine where control efforts should be directed. Even broad generalizations about the likelihood of loss may be useful. One suggested approach is to classify probability as almost nil (meaning that, in the opinion of the risk manager, the event is probably not going to happen), slight (meaning that while the event is possible, it has not happened and is unlikely to occur in the future), moderate (meaning that the event has occasionally happened and will probably happen again), and definite (meaning that the event has happened regularly in the past and is expected to occur regularly in the future).22 Although probability estimates such as these may be of some help in risk management decisions, when the appropriate data are available, more precise mathematical estimates of the probabilities will be useful. Some organizations, by virtue of their size and the scope of their operations, may be able to use probability estimates in risk financing decisions.

![]()

Consideration of Alternatives and Selection of the Risk Treatment Device

Once the risks have been identified and evaluated, the next step is consideration of the approaches that may be used to deal with risks and the selection of the technique that should be used for each one.

The Choice This phase of the risk management process is primarily a problem in decision making; more precisely, it is deciding which of the techniques available should be used in dealing with each risk. The extent to which the risk management personnel must make these decisions on their own varies from organization to organization. Sometimes, the organization's risk management policy establishes the criteria to be applied in the choice of techniques, outlining the rules within which the risk manager may operate. If the risk management policy is rigid and detailed, there is less latitude in the decision making done by the risk manager. He or she becomes an administrator of the program rather than a policy maker. In instances in which there is no formal policy or in which the policy has been loosely drawn to permit the risk manager a wide range of discretion, the position carries much greater responsibility.

In deciding which of the available techniques should be used to deal with a given risk, the risk manager considers the size of the potential loss, its probability, and the resources that would be available to meet the loss if it should occur. The benefits and costs in each approach are evaluated, and then, on the basis of the best information available and under the guidance of the corporate risk management policy, the decision is made. Some of the important considerations in the selection of the most appropriate technique are discussed later in this chapter.

![]()

Implementation of the Decision

The decision is made to retain a risk. This may be accomplished with or without a reserve and with or without a fund. If the plan is to include the accumulation of a fund, proper administrative procedure must be set up to implement the decision. If loss prevention is selected to deal with a particular risk, the proper loss prevention program must be designed and implemented. The decision to transfer the risk through insurance must be followed by the selection of an insurer, negotiations, and placement of the insurance.

![]()

Evaluation and Review

Evaluation and review must be included in the program for two reasons. First, the risk management process does not take place in a vacuum. Things change; new risks arise and old risks disappear. The techniques that were appropriate last year may not be the most advisable this year, and constant attention is required. Second, mistakes are sometimes made. Evaluation and review of the risk management program permits the risk manager to review decisions and discover mistakes, ideally before they become costly.

How does one review a risk management program? Basically, by repeating each of the steps in the risk management process to determine whether past decisions were proper in the light of existing conditions and if they were properly executed. The risk manager reevaluates the program's objectives, repeats the identification process to ensure, insofar as possible, that it was performed correctly, and then evaluates the risks that have been identified and verifies that the decision on how to address each risk was proper. Finally, the implementation of the decisions must be verified to make sure they were executed as intended.

Evaluation and Review as Managerial Control The evaluation and review phase of the risk management process is the managerial control phase of the risk management process. The purpose of controlling is to verify that operations are going according to plans. Control requires three steps: (a) setting standards or objectives to be achieved; (b) measuring performance against those standards and objectives; and (c) taking corrective action when results differ from the intended results. In this context, it should be recognized that a disastrous loss need not occur for performance to deviate from what is intended. Because risk management deals with decisions under conditions of uncertainty, adequate performance is measured based on not only whether the organization has survived but whether it would have survived under a different set of more adverse circumstances. The existence of an inadequately addressed exposure with catastrophic potential represents a deviation from the intended objective. It is this type of deviation from objectives that the risk management control process is intended to address.

Quantitative Performance Standards Ideally, standards should be quantified whenever possible. One quantifiable measure of risk management performance that is frequently suggested is the cost of risk, which is the total expenditure for risk management, including insurance premiums paid and retained losses, expressed as a percentage of revenues. RIMS publishes annual studies on the cost of risk, which make it convenient for the risk manager to compare the risk management costs of the organization with those of other firms in the same industry. The cost of risk varies from industry to industry, yet it generally averages in the neighborhood of 1 percent of revenues. Although the cost of risk may fluctuate because of factors over which the risk manager has no control, it is a useful standard when properly interpreted.

Quantitative performance standards are more prevalent in the area of risk control than for risk financing functions. Standard injury rates reflecting frequency and severity are available as benchmarks for measuring performance in the area of employee safety. Similarly, motor vehicle accident rates and other frequency and severity rates are useful benchmarks in measuring risk control measures.

Risk Management Audits Although evaluation and review is an ongoing process that is performed without interruption, the risk management program should periodically be subjected to a comprehensive review called a risk management audit. Most people are familiar with the term audit as it is used in the accounting field, where it refers to a formal examination of financial records by public accountants to verify the accuracy, fairness, and integrity of the accounting records. The term audit has a second meaning, which is any thorough examination and evaluation of a problem, and it is this second meaning that is implied in the term risk management audit. A risk management audit is a detailed and systematic review of a risk management program, designed to determine whether the objectives of the program are appropriate to the needs of the organization, whether the measures designed to achieve those objectives are suitable, and whether the measures have been properly implemented.

Risk management audits may be conducted by an external party or they may be performed internally. When the risk management department has the required in-house expertise, it may establish a system for internal audits of the risk management function on a regularly scheduled basis. Although internal audits may lack the objectivity of external audits and are not substitutes for external audits, they can provide many of the same benefits. The benefits of internal audits are maximized when they are conducted, to the extent possible, in the same way as an external audit.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

risk management

risk control

risk avoidance

risk reduction

loss prevention

loss control

risk financing

risk retention

risk transfer

risk sharing

security function

insurance management

enterprise risk management

financial risk management

risk management process

determination of objectives

identification of the risks

evaluation of the risks

consideration of alternatives and selection of the risk treatment device

implementation of the decision

evaluation and review

insurance policy checklists

risk analysis questionnaires

flow process charts

critical risks

important risks

unimportant risks

risk management policy

post-loss objectives

pre-loss objectives

survival

cost of risk

maximum retention limit

fact finders

exposure checklists

financial statement method

flowcharts

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. According to the text, risk management represents the merging of three specialties. Identify these specialties and explain the contribution of each to modern risk management theory.

2. Identify the two broad approaches to dealing with risk recognized by modern risk management theory.

3. Identify and briefly describe the four basic techniques available to the risk manager for dealing with the pure risks facing the firm. Give an example of each technique.

4. The text states the emergence of risk management was a revolution that signaled a dramatic shift in philosophy. What was this change in philosophy?

5. Identify and briefly describe the six steps in the risk management process.

6. Briefly describe the development of risk management as a function of business in the United States. In your opinion, what were the primary motivating forces and the strategic factors that led to the development of risk management?

7. Describe the responsibility of the risk manager and the risk manager's position within the organization.

8. What is the relationship between risk management and insurance management? In your answer, you should demonstrate an understanding of the difference between the two fields.

9. Identify two common misconceptions about risk management, and explain why these misconceptions developed.

10. Distinguish among traditional risk management, financial risk management, and enterprise risk management.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. In some sense, a risk manager must be a “jack of all trades” because of the breadth of his or her activities. Identify several areas in which a risk manager should be knowledgeable, and explain why this would be useful. What type of educational background should a risk manager have?

2. In a large, multidivision company, risk management may be centralized or decentralized. Which approach, in your opinion, is likely to produce the greatest benefits? Why?

3. The American Risk and Insurance Association has argued that risk management should be added to the required core of knowledge in business administration. To what extent do you agree or disagree that risk management should be a required course in a business curriculum?

4. Describe risk management's direct contribution to profit.