CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Identify two decision models from the field of decision theory that may be used in risk management decision making and explain the circumstances in which each is applicable

- Identify the three rules of risk management and explain how they relate to the management science decision models

- Identify the common errors in buying insurance and explain how these errors can be avoided

- Select the appropriate technique for dealing with a particular risk, based on the characteristics of the risk

- Identify the factors that should be considered in the selection of an insurance agent and an insurance company

- Explain the advantages and disadvantages of self-insurance

- Describe the general nature of captive insurance companies

Now that we have examined the concepts of risk, risk management, and insurance, we turn to a discussion of risk management applications and the ways in which risk management concepts can be applied in managing risks. We begin with a discussion of the considerations in selecting the technique that will be used to address the various risks facing the individual or organization. Next, we will discuss the ways in which these considerations influence insurance-buying decisions. Finally, we will examine some of the alternatives to commercial insurance.

![]()

RISK MANAGEMENT DECISIONS

![]()

Once the risks have been identified and evaluated, the next step is consideration of the techniques that should be used to deal with each risk. This phase of the risk management process is primarily a problem in decision making; more precisely, it is deciding which of the techniques available should be used in dealing with each risk. Numerous strategies have been suggested for this phase of the risk management process. Some have proven to be more productive than others.

![]()

Utility Theory and Risk Management Decisions

Some theorists have suggested that utility theory be used as an approach to risk management decisions, especially regarding retention and transfer.1 They would use the expected value concept to compare an individual's preferences (utility) for different states of uncertainty (e.g., “Which would you prefer, a 10% chance of losing $1000 or a 1% chance of losing $10,000?”). Once the individual's preference for different states of uncertainty (his or her “utility function”) has been derived, it is used in a calculation that multiplies utility units by the probability that each level of loss might occur. This calculation is made for each decision being considered, and the decision that produces the lowest expected loss of utility is selected.

We will not discuss the process by which the utility function is derived, primarily because we do not believe it is a useful tool for risk management decisions. The theory of marginal utility was constructed by economists in an attempt to explain why people make the consumer choices they do. It does not and is not intended to provide guidance on the decisions people should make.2 Using a utility function (real or hypothetical) as the basis for risk-related decisions could conceivably lead to more consistent decisions, but there is no reason to believe that those decisions would be good. They might be consistent, but consistently bad, decisions.

![]()

Decision Theory and Risk Management Decisions

The most appropriate approaches to risk management decisions are drawn from decision theory and operations research. The types of problems addressed by the decision theory approach to decision making are those for which there is not an obvious solution, a situation that characterizes many risk management decisions. The decision theory approach aims at identifying the best decision or solution to the problem.

Cost-Benefit Analysis In theory, each of the techniques of risk management should be used when it is the most effective technique for dealing with a particular risk. Further, each technique should be used up to the point at which each dollar spent on the measure will produce a dollar in savings through reduction in losses. This is simply cost-benefit analysis, which attempts to measure the benefit of any course of action against its costs.

Applying marginal benefit-marginal cost analysis to the risk management problem is complicated by several factors. The first is that while costs are measurable, benefits may not be measurable. When there is uncertainty about what the benefits will be, the decision requires that one estimate the expected value of the benefits, computed from the potential payoffs and the probabilities of various outcomes.

Expected Value Decision theory literature suggests three classes of decision-making situations, based on the knowledge the decision maker has about the possible outcomes or results (called states of nature). The first is decision making under certainty, which defines the situation in which the outcomes that result from each choice are known (and therefore when benefit-cost analysis is appropriate). The second is decision making under risk, in which the outcomes are uncertain but probability estimates are available for the various outcomes. Finally, decision making under uncertainty means that the probability of occurrence of each outcome is unknown.

In decision making under risk, for which the probability of different outcomes can be predicted with reasonable precision, expected values can be computed to determine the most favorable outcome. For example, a blackjack player with a count of 16 who “stands” against the dealer's 10 will lose 78.8 percent of the time and win 21.2 percent of the time, for an expected value of −0.576. If the player “hits” the 16 against the dealer's 10, he or she will lose 77.9 percent of the time and will win 22.1 percent of the time, for an expected value of −0.557. Thus, the expected value is higher if the player hits 16 against the dealer's 10 than if he or she stands.

In some situations, the expected value criterion that is used in decision making under risk can be used as a strategy for risk management decisions, such as the choice between retention and the purchase of insurance. A decision or choice is described in terms of a payoff matrix, a rectangular array whose rows represent alternative courses of action and whose columns represent the outcomes or states of nature. The expected value for a particular decision is the sum of the weighted payoffs for that decision. The weight for each payoff is the probability that the payoff occurs multiplied by the value.

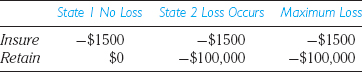

For the purpose of illustration, assume a loss exposure of $100,000, for which the probability is estimated to be .01. Assume further that insurance against loss from this exposure will cost $1500 annually. The expected value for the two possible choices (insure and retain), given the two possible states of nature (No Loss and Loss Occurs), would be computed as follows:

According to the expected value criterion, the decision to retain is the more attractive. The expected value of the decision Insure is −$1500: (−$1500 × .01 + −$1500 × .99). For the decision Retain, the expected value is −$1000. If the decision is made on the basis of expected value, retention will be selected as the appropriate decision since −$1000 is less than −$1500. Parenthetically speaking, given an accurate estimate of probabilities, the expected value criterion will always suggest retention over transfer through insurance. This is because the premium for insurance includes the expected value of the loss and includes the cost of operating the insurance mechanism. Assuming that the insurer has an accurate estimate of probability, the cost of insurance is always greater than the expected value of a loss.

There are two problems with the expected value model for risk management decisions. The first is that the expected value model requires that the decision maker have accurate information on the probabilities, which is unavailable as often as desired. Second, and more important, even when accurate probability estimates are available, actual experience will deviate from the expected value. Although the long-run expected value of the retention strategy is −$1000, a loss of $100,000 could occur. If a $100,000 loss is unacceptable to management, the long-run expected value is irrelevant. There is little consolation following the bankruptcy that results from the uninsured $100,000 loss in that the retention strategy would have been the cost-effective strategy in the long run if the firm had survived.

Pascal's Wager The defects in the expected value strategy suggested the need for a different strategy in some situations. Blaise Pascal, a seventeenth-century mathematician considered the situation in which the probability of an outcome is unknown and in which there is a significant difference in the possible outcomes. The question about which Pascal was concerned was the existence of God. For our purposes, the importance of Pascal's analysis of this question is not the question itself but the logic of the analysis and its implications for risk management. The analysis led Pascal to what one author has cited as the beginning of the theory of decision making.3

According to Pascal, there is no way to estimate the probability or likelihood that God exists. One believes in God or one does not. The decision, therefore, is not whether to believe in God but rather whether to act as if God exists or does not exist. The choice, in Pascal's view, is, in effect, a bet on whether or not God exists. According to Pascal's wager, if one bets that God exists, he or she will lead a good life. A person who chooses to lead an evil life is wagering that God does not exist. If God does not exist, whether you lead a good life or a bad one is immaterial. But suppose, says Pascal, that God does exist. If you bet against the existence of God (by refusing to lead a good life), you run the risk of eternal damnation, while the winner of the bet that God exists has the possibility of salvation. Because salvation is preferable to damnation, for Pascal the correct decision is to act as if God exists.

Pascal's wager introduces two significant principles for decision making. The first is that some situations exist in which the consequence (magnitude of the potential loss) rather than the probability should be the first consideration. Put somewhat differently, there are some situations in which one of the outcomes is so undesirable that its possibility is unacceptable. The second is that even when dependable estimates of the probability are unavailable, decisions made under conditions of uncertainty can be made on a rational basis.4

Minimax Regret Strategy In modern decision theory, the equivalent of Pascal's strategy is known as minimax (standing for minimize the maximum) regret. In the minimax regret strategy, the decision maker attempts to minimize the maximum loss or maximum regret. For problems such as those in the area of risk management, in which payoffs such as costs are to be minimized, the maximum cost of each decision for each of the possible outcomes is listed, and the minimum of the maximums is selected as the appropriate choice, which gives rise to the term minimax. Returning to the $100,000 building with the $1500 insurance premium, an uninsured $100,000 loss represents the greater maximum loss and the choice Insure will minimize the maximum cost.

In risk management, the premise on which the minimax cost or minimax regret strategies are based is Pascal's contention that when the probability of loss cannot be determined, one should choose the option in which the potential for regret is the lowest. The minimax cost or minimax regret strategies are appropriate when the maximum cost associated with one of the possible states of nature is unacceptable to management. This would be the case, for example, when the potential loss that might arise is beyond the firm's ability to bear.

Whereas the expected value strategy will always suggest retention as the preferred approach, a minimax strategy will always suggest transfer.

![]()

The Rules of Risk Management

The expected value strategy and the minimax strategy have application in risk management decisions. Because the decisions recommended by these strategies are diametrically opposed, the obvious key is to determine the situations in which each strategy should be applied. This question was addressed in the first textbook on the subject of risk management. One of the earliest contributions to the risk management field was the development of a set of “rules of risk management.”5 These rules are commonsense principles applied to risk situations:

- Don't risk more than you can afford to lose.

- Consider the odds.

- Don't risk a lot for a little.

Simple as they appear, these three rules provide a basic framework within which risk management decisions can be made. Unfortunately, they are sometimes misunderstood and are often neglected.

Don't Risk More Than You Can Afford to Lose The first of the three rules, “Don't risk more than you can afford to lose,” is the most important. Although it does not necessarily tell us what should be done about a given risk, it does identify the risks about which something must be done. If we begin with the recognition that when nothing is done about a particular risk, that risk is retained, identifying the risks about which something must be done resolves into determining which risks cannot be retained. The answer is explicitly stated in the first rule.

The most important consideration in determining which risks require some specific action is the maximum potential loss that might result from the risk. If the maximum potential loss from a given exposure is so large that it would result in an unbearable loss, retention is unrealistic. The possible severity must be reduced to a manageable level or the risk must be transferred. If severity cannot be reduced and the risk cannot be transferred, it must be avoided. In decision theory terms, “Don't risk more than you can afford to lose” identifies the decisions for which the minimax cost or minimax regret strategy is appropriate.

Consider the Odds If an individual can determine the probability that a loss may occur, he or she is in a better position to deal with the risk than would be the case without such information. However, it is possible to attach undue significance to such probabilities since the probability that a loss may or may not occur is less important than the possible severity if it does occur. Even when the probability of loss is low, the primary consideration is the potential severity.

This is not to say that the probability associated with a given exposure is not a consideration in determining what to do about that risk. Just as the potential severity indicates the risk about which something must be done (i.e., the risks that cannot be retained), knowing whether the probability that a loss will occur is slight, moderate, or high can assist the risk manager in deciding what should be done about a given risk although not in the way that most people think.

A high probability is an indication that insurance is probably an uneconomical way of dealing with the risk. This is because insurance operates on the basis of averages. Based on past experience, the insurer estimates the amount that it must collect in premiums to cover the losses that will occur. In addition to covering the losses, the amount must cover the insurer's other expenses. Therefore, as paradoxical as it may seem, the best buys in insurance involve those losses that are least likely to happen. The higher the probability of loss, the less suitable is insurance as a device for dealing with the exposure.

The best buys in insurance are those in which the probability is low and the possible severity is high. The worst buys are those in which the size of the potential loss is low and the probability of loss is high. The most effective way to deal with those exposures in which the probability of loss is high is through loss prevention measures aimed at reducing the probability of loss.

The second rule of risk management, “Consider the odds,” suggests that the likelihood or probability of loss may be an important factor in deciding what to do about a particular risk. But which risks? Logically, consideration of the odds is limited to those situations in which the first rule, “Don't risk more than you can afford to lose,” does not apply. For decisions in which one of the possible states of nature is ruin, the minimax cost or minimax regret strategies are appropriate.

Having limited our application of probability to situations in which ruin is not one of the possible outcomes or states of nature, even in this limited set of decisions, situations in which probability theory is useful abound. Among the more fertile fields for analysis are the selection of deductibles, and the decision to insure or retain moderate losses.

Don't Risk a Lot for a Little Although the first rule provides guidance for those risks that should be transferred (those involving catastrophic losses in which the potential severity cannot be reduced), and the second rule provides guidance for those that should not be insured (those in which the probability of loss is very high), a residual class of risks remains for which another rule is needed.

The third rule dictates there should be a reasonable relationship between the cost of transferring risk and the value that accrues to the transferor. The rule provides guidance in two directions. First, risks should not be retained when the possible loss is large (a lot) relative to the premiums saved through retention (a little). On the other hand, instances occur in which the premium that is required to insure a risk is disproportionately high relative to the risk transferred. In these cases, the premiums represent “a lot” while the possible loss is “a little.”

Although the rule “Don't risk more than you can afford to lose” imposes a maximum level on the risks that should be retained, the rule “Don't risk a lot for a little” suggests that some risks below this maximum retention level should also be transferred. The maximum retention level should be the same for all risks, yet the actual retention level for some exposures may be less than this maximum.

![]()

Risk Characteristics as Determinants of the Tool

From the foregoing discussion, it is clear that there are some risks that should be transferred and some that should be retained. It is also clear that both transfer and retention are unsatisfactory in other cases, and that avoidance or reduction is necessary. What determines when a given approach should be used? It is the characteristic of the risk that determines which of the four tools of risk management is most appropriate in a given situation. Under what circumstances is each of the tools appropriate?

Based on the previous discussion, it is possible at this point to summarize a few general guidelines with respect to the relationship of the various tools and particular risks. The following matrix categorizes risks into four classes, based on the combination of frequency (probability) and severity of each risk. Although real-world risks are not divided so conveniently, most exposures can be classified according to their frequency and potential severity.

When the possible severity of loss is high, retention is unrealistic, and some other technique is necessary. However, we have also noted that when the probability of loss is high, insurance becomes too costly. Through a process of elimination, we conclude that the appropriate tools for dealing with risks characterized by high severity and high frequency are avoidance and reduction. Reduction may be used when it is possible to reduce the severity or the frequency to a manageable level. Otherwise, the risk should be avoided.

Risks characterized by high severity and low frequency are best dealt with through insurance. The high severity implies a catastrophic impact if the loss should occur, and the low probability implies a low expected value and a low cost of transfer.

Risks characterized by low severity and high frequency are most appropriately dealt with through retention and reduction: retention because the high frequency implies that transfer will be costly, and reduction to decrease the aggregate amount of losses that must be borne.

Finally, those risks characterized by low severity and low frequency are best handled through retention. They seldom occur, and when they do happen, the financial impact is inconsequential.

Although not all risks will fit precisely into the categories in the chart, most exposures can be classified according to their frequency and potential severity. In those instances in which the probability or severity is not “high” or “low,” the principles may be modified by judgment.

![]()

The Special Case of Risk Reduction

From a theoretical perspective, decisions regarding the application of risk management techniques should be made on the basis of a marginal benefit marginal cost rule. This means that from the viewpoint of minimizing costs, each of the techniques for dealing with risk should be utilized when that particular technique represents the lowest cost approach to the particular risk in question. Also, a given technique should be used only up to that point at which the last dollar spent achieves a dollar reduction in the cost of losses or risk and no further. However, this basic principle must sometimes be modified in the case of loss prevention and control methods. Humanitarian considerations and legal requirements sometimes dictate that loss prevention and control measures go beyond the optimal marginal cost-marginal benefit point. For example, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) requires employers to incur expenses for job safety loss prevention and control measures that might not be justified on a pure cost-benefit basis.6

![]()

BUYING INSURANCE

![]()

Although insurance is only one of the techniques available for dealing with the pure risks that the individual or the firm faces, many of the risk management decisions boil down to a choice between insurance and noninsurance. Although the basic principles of risk management have been discussed, it may be useful to examine the application of a few of these principles to the area of insurance buying.

![]()

Common Errors in Buying Insurance

In general, the mistakes that most people make when buying insurance fall into two categories: buying too little and buying too much. The first, which is potentially the more costly, consists of the failure to purchase essential coverages that can leave the individual vulnerable to unbearable financial loss. Unless the insurance program is designed to protect against the catastrophes to which the individual is exposed, an entire life's work can be lost in a single uninsured loss. On the other hand, it is possible to purchase too much insurance, buying protection against losses that could more economically be retained. The difficulty in buying the right amount of insurance is compounded by the possibility of making both mistakes at the same time. In fact, although most people spend enough to provide an adequate insurance program, too often they ignore critical risks, leaving gaping holes in the overall pattern of protection while insuring unimportant risks, using valuable premium dollars that would more effectively be spent elsewhere.

Some insurance buyers turn the entire decision-making process over to an outside party such as an insurance agent or broker. In a sense, they delegate the responsibility for policy decisions and administration to this outside party. Although such a course of action may relieve the insurance buyer of the decision burden, it may not result in an optimal program. When the choices involved in the purchase of insurance are delegated to an outside party, there is often a tendency to insure exposures that might better be retained. An insurance agent does not enjoy being in a defensive position when a loss takes place and, when charged with the overall responsibility for the insurance decisions, may decide to protect himself or herself as well as the client by opting for more, rather than less, insurance. While a competent agent or broker is a valuable source of advice, the basic rules governing the decisions should be made by the person or persons most directly involved since these decisions are likely to have large financial impact over the long run in either premiums paid or losses sustained if hazards are not insured.

![]()

Need for a Plan

The basic problem facing any insurance buyer is that of using the available premium dollars to the best possible advantage. To obtain maximum benefit from the dollars spent, some sort of plan is needed. Otherwise, there is a tendency to view the purchase of insurance as a series of individual, isolated decisions, rather than a single problem, and there are no guidelines to provide for a logical consistency in dealing with the various risks faced.

A Priority Ranking for Insurance Expenditures Such a plan can be formulated to set priorities for the allocation of premium dollars on the basis of the previously discussed classification of risks into critical, important, and unimportant, with insurance coverages designed to protect against these risks classified as essential, desirable, and optional.

- Essential insurance coverages include those designed to protect against loss exposures that could result in bankruptcy. Insurance coverage required by law is also essential.

- Important insurance coverages include those that protect against loss exposures that would force the insured to borrow or resort to credit.

- Optional insurance coverages include those that protect against losses that could be met out of existing assets or current income.

Large-Loss Principle: Essential Coverages First The primary emphasis on essential coverages follows the first rule of risk management and the axiom that the probability a loss may or may not occur is less important than its possible size. Since the individual must of necessity assume some risks and transfer others, it seems only rational to begin by transferring those that he or she could not afford to bear. One frequently hears the complaint, “The trouble with insurance is that those who need it most can least afford it.” There is considerable truth in this statement. The need for insurance is dictated by the inability to withstand the loss in question if the insurance is not purchased, so although it is true that those who need insurance are those who can least afford it, it is also true they are the ones who can least afford to be without it. In determining whether or not to purchase insurance in a particular situation, the important question is not, Can I afford it? but rather, Can I afford to be without it?

When the available dollars cannot provide all the essential and important coverages you want to carry, the question becomes where to cut. One approach is to assume a part of the loss in connection with these coverages. You can do this by adding higher deductibles to these coverages, thereby freeing dollars for others that you desire. In many lines of insurance, full coverage is uneconomical because of the high cost of protecting against small losses. If you exclude coverage for these losses through deductibles, the premium credits granted may permit you to purchase others that are desirable.

Insurance as a Last Resort: Optional Coverages As we have seen, insurance always costs more than the expected value of the loss. This is because in addition to the expected value of the loss (the pure premium), the cost of operating the insurance mechanism must also be borne by the policy-holders. For this reason, insurance should be considered a last resort, to be used only when absolutely necessary.

It is in connection with this latter aspect of insurance that many people fail to appreciate the appropriate function of the mechanism. The insurance principle should not be utilized to indemnify for small, relatively certain losses. These can more desirably be carried as a part of the cost of production in a business or as one small cost to an individual of maintaining self and family. Why should one want to collect from an insurance company for the two or three shingles blown off the roof during a windstorm? Why should any individual with any degree of affluence want a $100 deductible on an automobile? In many instances, these small, relatively certain losses can be eliminated from the insurance operation by specifically excluding them or by using a deductible. Insurance companies, in providing indemnity for such small losses in their contracts, are as guilty of the misuse of the insurance principle as are the insureds who buy them.

There is nothing intrinsically wrong with optional coverages. They are just a poor way to spend the limited number of dollars that are available for the purchase of insurance. If the individual's psychological makeup is such that he or she desires protection against even the smallest type of loss, optional coverages are probably all right. The real problem with such coverages is that the individual who insures against small losses often does so at the expense of exposures that involve financially catastrophic losses. Although an individual or business firm might desire some optional coverages, they should be purchased only after all the important ones have been purchased. Of course, all essential coverages should be bought before premiums are spent on the less critical important coverages. In this way, the premium dollars will be spent where they are most effective: protecting first against those losses that could result in bankruptcy; next against those that would require resort to credit; and finally, when all other exposures have been covered, against those losses that could be met out of existing assets or current income.

Advantages of Deductibles It makes good sense to use the deductible in insurance contracts, whether bought by an individual or a business. The premium reduction normally more than compensates for the risk that is retained. Take the case of automobile collision insurance. The cost difference between a $200 deductible and a $500 deductible coverage may be substantial. The difference will depend on the rates applicable in the area and the age and value of the car. As an example, in a midwestern city, one insurer quoted a premium on collision coverage with a $200 deductible for a medium-priced, late-model car, written for a 23-year-old unmarried male operator, at $806 per year. The cost with a $500 deductible was $630 per year, a difference of $176. Thus, the individual is paying $176 for $300 in coverage. If the young man who purchases $200 deductible coverage owned a car worth $300, and was offered collision coverage on it for $176—even without a deductible—he would reason that the premium was too high and that the car was not worth insuring. Why is it not also too high to pay $176 for $300 in coverage on a car that is worth more?

![]()

Other Considerations in the Choice Between Insurance and Retention

The choice between the risk-financing alternatives—retention and transfer—is sometimes dictated by the first rule of risk management. When a risk exceeds the organization's risk-bearing capacity, it must be reduced or transferred. In other cases, however, where the organization could afford the loss, there may still be advantages in transfer. It may be desirable, for example, to obtain the services of an insurance company for the investigation and settlement of liability losses or the inspection services that are offered in connection with boiler and machinery insurance. In addition, there are some instances in which risk transfer will produce economies even though the cost of insurance exceeds expected value. Two considerations in particular may affect the transfer-retention decision: the cost of financing risk and the tax treatment of insurance premiums and retained losses.

The Cost of Financing Risk The choice between transfer and retention and the way in which retention and transfer should be combined should recognize the distinction between the cost of financing losses and that of financing risk. A review of terminology may be helpful. A loss is a decline in or disappearance of value due to a contingency. Not all losses involve risk, which is the possibility of a deviation from what is expected or hoped for.

Consider a firm that owns buildings worth $1,000,000. Insurance on the buildings will cost $30,000. Assuming a loss ratio of about 65 or 66 percent, the expected loss (i.e., the average loss per insured) is roughly $20,000. In fact, let us also assume that the manufacturer's past losses have been about average, or $20,000 a year. If expected losses are $20,000 a year but could be as much as $1,000,000, the risk is $980,000 ($1,000,000 minus $20,000). The $20,000 represents a predictable loss, while the remaining $980,000 represents “risk,” which like the cost of losses, can be transferred or retained.

If the firm decides to retain the entire risk of loss, it will presumably continue to incur $20,000 in losses annually. In addition, to protect against the possibility of a total $1,000,000 loss, it must maintain a liquid reserve of $980,000. The cost of the retention program will be the $20,000 in annual losses that must be paid plus the opportunity cost on the $980,000 reserve. This opportunity cost is measured as the difference between the return that will be earned on the reserve (which must be kept in a semiliquid form), and the return that could be realized if the $980,000 were applied to the firm's operations. If the average return on funds applied to operations is, say, 15 percent and the interest that can be earned on the invested reserve is 6 percent, the opportunity cost is $88,200 ([15% minus 6%] × $980,000). Thus, the cost of insuring is $30,000, while the cost of retention is $108,200 ($20,000 in losses plus the $88,200 opportunity cost).7 A more complete analysis would consider the effect of taxes on both costs. Assuming a combined state and federal marginal tax rate of 50 percent, the cost of insurance would be $15,000, and the cost of retention would be $54,100.

Tax Considerations in Risk Financing Decisions One element that should be considered in the choice of the approach to risk financing for a particular risk is the impact that taxes may have on insurance costs and losses. In the case of a business firm, for instance, property and liability insurance premiums are a deductible business expense as are uninsured losses. However, contributions to a funded retention program are not deductible. The inability to deduct contributions to a reserve fund does not eliminate the tax deductibility of self-insured losses; it merely forces companies to wait until they incur a loss before taking the deduction. The decision to purchase insurance may be influenced by uninsured losses being deductible in the year in which they occur only to the extent of profit during that year and that the tax deduction resulting from the uninsured loss may be reduced by low profits in the year in which it occurs.8

![]()

Selecting the Agent and the Company

Although the selection of an insurance company is an important aspect of the insurance-buying process, in most cases the individual is probably well advised to focus primary attention on selecting the agent rather than the company. When an insurance policy is purchased, a part of the premium goes to the insurance company to pay for the protection. A second part is compensation to the agent for the service he or she provides to the insured. The most important part of this service consists of the advice the agent gives. Careful selection of the adviser is a fundamental part of insurance buying. From the point of view of the insured, the primary qualifications for a good agent are knowledge of the insurance field and an interest in the needs of the client. One indicator of a knowledgeable and professional agent is a professional designation. The Chartered Property and Casualty Underwriter (CPCU) and the Chartered Life Underwriter (CLU) designations indicate that the agent is sufficiently motivated to work in a formal educational program for professional development. However, many competent and knowledgeable agents do not have these designations.

The insured may receive assistance from the agent in selecting an insurer if the agent represents several companies. However, in the case of many life insurance agents and certain property and liability agents who represent only one company, the selection of the agent will automatically include the selection of the company. In choosing a company, the major consideration should be its financial stability. In addition, certain aspects of the company's operation, such as its attitude toward claims and cancellation of policyholders' protection, are important. Finally, cost is a consideration.

Financial Stability Financial stability is the single most important factor to consider when selecting an insurer. An insurance policy has little value if the insurer does not have the financial resource to pay the claim. Analysis of an insurance company's strength follows the same principles used in the financial analysis of any corporation. However, industry accounting practices are sufficiently specialized that it is advisable for a layperson to consult an evaluation service rather than attempt the analysis alone. Data on the financial stability of insurance companies are available from several sources that specialize in providing information on the companies' financial strength, the efficiency of their operations, and the caliber of management.

For many years, the principal rating agency for both property and liability insurers and life insurers was the A.M. Best Company (A. M. Best). Today, an insurer may also be rated by Standard and Poor's Corporation, Moody's Investor Services, Inc. (Moody's), Fitch, Inc. (formerly Duff and Phelps), and Weiss Ratings. Each of the ratings services uses a different classification system, and the categories have different designations. All rating services, however, distinguish between insurers whose financial condition is deemed adequate and those insurers that are classified as vulnerable or weak. The ratings and the description assigned by the rating agency to the various classes are summarized in Table 4.1.9

A.M. Best has been rating insurers since 1900 and rates the vast majority of insurers. In addition, it assigns a “not rated” classification to those insurers that are not rated. The primary information source for these ratings is the annual and quarterly financial statements filed by insurers with their regulators. This is supplemented by other publicly available documents (such as SEC filings), company responses on A.M. Best questionnaires, and annual business plans. In addition, A.M. Best engages in an interactive exchange of information with the insurer's management. All quantitative and qualitative information is used to evaluate the company's balance sheet strength, operating performance, and business profile. Based on that evaluation, A.M. Best assigns a Financial Strength Rating from A++ to F.

The rating processes for Standard and Poor's, Moody's, and Fitch involve analysis of quantitative and qualitative information, with extensive interaction with the insurer's management. The Standard and Poor's process, for example, examines the insurer's competitive position, quality of management, corporate strategy, operating performance, investments, capital adequacy, liquidity, financial flexibility, and enterprise risk management. Each rating agency maintains its own capital adequacy model, which assesses the minimum amount of capital an insurer should have for various rating categories.

Weiss ratings are based primarily on publicly available information, primarily the insurer's financial statements, but involve limited or no interaction with company management. Thus, these ratings do not reflect dialogue with insurer management or the availability of nonpublic information. For those companies that choose not to engage in the interactive ratings process, Standard and Poor's and A.M. Best may assign ratings based solely on public information. The A.M. Best rating is called a Public Data Rating and follows the same scale as the Financial Strength Ratings, but has “pd” at the end of the rating. Standard and Poor's provides a Qualified Solvency Rating based on public information only, denoted by a “pi” after the rating.

When properly used, the ratings assigned by A.M. Best and the other rating services can be effective tools for avoiding delinquent insurance companies. In utilizing the ratings for both property and liability insurers and life insurers, the ratings should be checked for a period of years. If there has been a downward trend in the rating, further investigation into the cause of the change is warranted. For many years, the suggested standard was an A+ rating from A.M. Best for a period of at least six years.10 A noted authority recommends that one should select a life insurance company that has high ratings from at least two of the four rating firms other than A.M. Best.11 That seems like a reasonable standard for property and liability insurers as well.

TABLE 4.1 Rating Categories Used by Insurer Rating Agencies

When comparing the ratings assigned by different rating services, one should review the description of the rating assigned by each service. Although all the agencies divide insurers into approximately the same number of ratings categories, the financial strength assigned to the categories varies, and a ranking in the top six categories by one service may represent a different evaluation from a ranking in the top six categories of another service. Table 4.1 indicates the descriptions assigned to the categories by the rating agencies themselves and the dividing line used by each service in distinguishing strong companies from weaker companies.

Treatment of Policyholders The second important factor in selecting an insurer is how it treats its policyholders. For example, claims should be paid fairly and in a timely manner. While it can be difficult to get reliable information on a company's performance in this area, there are some tools a consumer may use. Talking to other customers, particularly those who have had claims, can be useful. In addition, most state insurance departments offer complaint information on insurers that do business in the state. This will tell you how many complaints have been filed against the company, what types of complaints, and how the company compares with others in its complaint frequency. Complaints may be related to increases in premiums, cancellations or nonrenewals, failure to pay claims in a timely manner, or the amount of the claims payment. Some states attempt to distinguish justified complaints from other complaints. In other states, the total complaints filed may be listed. Another source of information on consumer complaints is the Consumer Information Source website of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC).12

Cost Finally, cost is a factor. Prices vary from company to company, and a little effort in comparing prices can save the consumer money.13 However, cost is less important than the insurer's financial stability and treatment of policyholders. Simply stated, a low-premium insurance company that is financially unstable and cannot be depended on to pay its claims in a timely manner is a bad value.

![]()

ALTERNATIVES TO COMMERCIAL INSURANCE

![]()

With the growth of risk management and the increased emphasis on finding the most appropriate technique for dealing with risk, alternatives to commercial insurance and to the traditional forms of retention have developed. These include self-insurance programs, captive insurers, risk retention groups, risk-sharing pools, and catastrophe bonds. The alternatives to commercial insurance have developed for a variety of reasons. In some cases, such as self-insurance programs for employer-provided health insurance, commercial insurance alternatives are available, but businesses and other organizations have found they can achieve economies through self-insured programs. In other cases, the alternatives were adopted because of a perceived failure of the commercial insurance market. Faced with escalating insurance costs and, in some instances, the inability to obtain various types of liability insurance, some organizations opted to self-insure or “go bare,” paying claims directly out of their income. Other organizations banded together to form group-owned captives or risk retention groups. In the case of public entities, risk-sharing pools were formed in many states. More recently, some companies have transferred risk to the capital markets via catastrophe bonds and other capital markets instruments.14

![]()

Self-Insurance

In the preceding chapter, we noted that although self-insurance is technically a definitional impossibility, the term has found widespread acceptance in the business world. It is widely used (and understood) and there seems little sense in ignoring the widespread use of an established and accepted term.15 Although there are theoretical defects in the term self-insurance, it is a convenient way of distinguishing retention programs that utilize insurance techniques from those that do not. Self-insurance programs are distinguished from other retention programs primarily in the formality of the arrangement. In some instances, this means obtaining approval from a state regulatory agency to retain risks, under specifically defined conditions. In other cases, it means the formal trappings of an insurance program, including funding measures based on actuarial calculations and contractual definitions of the exposures that are self-insured. When the self-insurance involves third parties (as in the case of employees covered under an employer-sponsored health insurance program), there is a need for the formal trappings of insurance, such as certificates of coverage and premiums. It is in this limited sense that the term self-insurance is used in this section.

Over the past three decades, the use of self-insurance by businesses and other organizations in dealing with risk has grown. In some areas, such as employer-sponsored health benefits for employees, it has become a major alternative to commercial insurance. Given the growing importance of this approach to dealing with risks, it seems appropriate that we consider some of the reasons for its growth.

Reasons for Self-Insurance Self-insurance, like any of the other risk management techniques, should be used when it is the most effective technique for dealing with a particular risk. The question is this: Under what circumstances is this the case? The main reason that firms elect to self-insure certain exposures is that they believe it will be cheaper to do so in the long run. This is particularly true when there is no need for the financial protection furnished by insurance. If losses are reasonably predictable, with a small likelihood of deviation from year to year, the risk can be retained.

- First, as explained earlier, the cost of insurance must, over the long run, exceed average losses. This is a mathematical truism. In addition to covering the losses that must be paid, the insurance premium must include a surcharge to cover the cost of operating the insurance company and its distribution system. In addition, commercial insurance is subject to state premium taxes, which represent a cost that must be paid by buyers. Self-insurance avoids certain expenses associated with the traditional commercial insurance market. These include, among other things, insurer overhead and profit, agents' commissions, and the premium taxes paid by insurers.

- The organization may believe that its loss experience is better than the average experience on which rates are made, or that the rating system inaccurately reflects the hazards associated with the exposure.

- In lines of insurance in which there are long delays between the time that a loss occurs and the time it is paid, insurers hold “reserves,” which represent liabilities for unpaid losses. Some organizations believe that the investment income from these reserves is inadequately reflected in rates, and they can reduce the cost of their insurance by capturing these investable funds through self-insurance.

- Self-insurers can avoid the social load in insurance rates that results from statutory mandates that insurers cover certain exposures in which premiums are less than the losses for those insured. These underwriting losses are passed on to other insureds in the form of higher premiums than their hazards justify.

Disadvantages of Self-Insurance Offsetting the perceived advantages of self-insurance are four disadvantages.

- The greatest disadvantage of self-insurance is that it can leave the organization exposed to catastrophic loss. This disadvantage can be eliminated if the self-insurer purchases reinsurance for potentially catastrophic losses, much in the same way as insurers do.

- Another disadvantage of a self-insurance program is there may be greater yearly variation of costs. When the yearly variation in costs from is great, the firm may lose the tax deduction for the losses that occur in years when there are no profits from which to deduct the losses.

- Self-insurance of some exposures can create adverse employee and public relations. There may be advantages to the organization in having its claims handled by an insurer (as opposed to the staff of the employer organization).

- Loss of ancillary services. There are certain services provided by insurers that are lost when a company adopts a self-insurance program. Most of these relate to loss prevention and claims handling. These services can be purchased separately from an insurer (under an arrangement called unbundling) or from specialty firms. The cost of obtaining these services must be included in the cost of the self-insurance when a comparison is made with commercial insurance.

As self-insurance became more popular among large corporations, insurers developed loss-sensitive rating programs and retention programs to compete with self-insurance. These include programs with large deductibles, experience rating (in which the insured's own loss experience is a major factor in the cost of the insurance), and cash flow plans, in which the premium payment arrangement allows the insured to retain premiums for investment until the funds are required for payment of losses.

![]()

Captive Insurance Companies

Captive insurance companies represent a special case of risk retention and, in some case, risk transfer. A captive insurance company is an entity created and controlled by a parent, whose main purpose is to provide insurance to that parent. It is an insurance company that provides insurance to its corporate owner or owners. There has been a steady growth in the number of captives since the 1950s, from a few hundred or so in the late 1950s to an estimated 6,000 in 2013.

Generally speaking, there are two types of captive organizations.

- Pure captives

- Association or group captives

Pure Captives A pure captive is an insurance company established by a noninsurance organization solely for the purpose of underwriting risks of the parent and its affiliates. Although the term captive has sometimes been applied loosely to include other affiliated insurers, as used here the term does not include insurance subsidiaries whose purpose is to write insurance for the general public.16

Historically, many captives were formed in foreign domiciles, partly because their formation was easier in these jurisdictions. Most of these so-called offshore captives were chartered in Bermuda, where the business climate is receptive to their formation.

Association Captives An association or group captive is an insurance company established by a group of companies to underwrite their own collective risks. These organizations are sometimes referred to as “trade association insurance companies” (TAICs) and as “risk retention groups.” The term risk retention group was added to the terminology of the captive field by the Risk Retention Acts of 1981 and 1986. A risk retention group is a group-owned captive organized under the provisions of the Risk Retention Act.

Captive Domiciles Captives have traditionally been classified as onshore or offshore. An onshore captive is incorporated and conducts business as a licensed insurer under one of the laws of the states. Historically, many captives were formed in foreign domiciles, partly because their formation was easier in these jurisdictions. Most of these so-called offshore captives were chartered in Bermuda or the Cayman Islands, where the business climate is receptive to their formation and regulatory requirements are less stringent. By 2013, however, over half of the state in the U.S. had adopted special laws applying to captive insurers. Today, over 1,000 captives are domiciled in the U.S.17

Tax Treatment of Captives One of the original rationales for captives was the hope that the parent company would be permitted to deduct premiums paid to the captive that would not be deductible as contributions to a self-insurance reserve. With the exception of certain group captives, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) rejected the strategy. From 1972 until 2001, the IRS argued that with a single-parent captive, there is no shifting of risk and no risk distribution (pooling of premiums). Because the premiums paid to the captive stayed within the economic family, the IRS held they were nondeductible contributions to a self-insurance reserve. The IRS frequently challenged deductions to single-parent captives and took this position with respect to premiums paid by the parent company, as well as by other companies within the same economic family.

Also in 2002, the IRS issued a Revenue Ruling (2002-89) that provided a safe harbor for a parent company to deduct premiums paid its captive.18 Under the safe harbor, adequate risk shifting and risk distribution was deemed to exist if the parent's premiums accounted for no more than 50 percent of the captive's income for the year. It should be noted that 50 percent is merely a safe harbor, and deduction may be permitted in cases in which smaller amounts of unrelated business are present. In fact, a 1992 case held that as little as 29 percent unrelated business in the captive may create adequate risk shifting and risk distribution to qualify for premium deduction by the parent.19

In addition to state premium taxes and “excess and surplus lines” taxes that apply to traditional insurers, a federal excise tax may apply to premiums of a captive insurer domiciled outside the United States.20

![]()

Risk Retention Act of 1986

The federal Risk Retention Act of 1986 exempted captives formed by groups for the purpose of sharing liability risks from much of state regulation except in the state in which they are domiciled. This 1986 act expanded a 1981 act, which had applied to product liability only. The 1986 law expanded the provisions of the law to apply to most liability coverages except workers' compensation and employers' liability.

Like its predecessor, the Risk Retention Act of 1986 authorized two mechanisms for group treatment of liability risks:

- Risk retention groups for self-funding (pooling)

- Purchasing groups for joint purchase of insurance

Although there had been little activity under the 1981 act, by July 2013, there were 257 operating risk retention groups and 894 insurance-purchasing groups.

Risk Retention Groups Risk retention groups are essentially group-owned insurers whose primary activity consists of assuming and spreading the liability risks of its members. As their name implies, risk retention groups are formed for the purpose of retaining or pooling risk. They are insurance companies, regularly licensed in the state of domicile and owned by their policyholders, who are shareholders. The members are required to have a community of interest (i.e., similar risks), and once organized, they can offer “memberships” to others with similar needs on a nation-wide basis. Risk retention groups can be licensed in only one state but may insure members of the group in any state. The jurisdiction in which they are chartered regulates the formation and operation of the group insurer. Once they are chartered in their state of domicile, risk retention groups may then operate in any other state by filing notice of their intent with the respective state insurance department.

Purchasing Groups In addition to risk retention groups, the Risk Retention Act of 1986 authorized insurance purchasing groups. Insurance purchasing groups are not insurers and do not retain risk. Rather, they purchase insurance on a group basis for their members. The coverage is purchased in the conventional insurance market, and state laws that prohibit the group purchase of property and liability insurance are nullified with respect to qualified purchasing groups.

Risk-Sharing Pools Risk-sharing pools are mechanisms closely related to and sometimes confused with association or group captives, but they constitute a separate technique. A group of entities may elect to pool their exposures, sharing the losses that occur, without creating a formal corporate insurance structure.21 In this case, a separate corporate insurer is not created, but the risks are nevertheless “insured” by the pooling mechanism.

Viewed from one perspective, pooling may be considered a form of transfer, in the sense that the risks of the pooling members are transferred from the individuals to the group. Viewed from a different perspective, pooling is a form of retention, in which the entity's risks are retained along with those of the other pooling members. This dual nature of pooling stems from the sometimes forgotten fact that in a pooling arrangement, members are insureds and insurers.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

cost-benefit analysis

utility theory

decision making under certainty

decision making under risk

decision making under uncertainty

expected value

Pascal's wager

minimax regret

rules of risk management

Don't risk more than you can afford to lose

Consider the odds

Don't risk a lot for a little

essential insurance coverages

important insurance coverages

optional insurance coverages

large-loss principle

insurance as a last resort

pure captive

association captive

risk retention group

insurance purchasing group

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. Describe the two strategies that may be employed in risk management decisions and explain the situation in which each is appropriate.

2. Explain why it may be difficult or inappropriate to use utility theory, cost-benefit analysis, and expected value in making risk management decisions.

3. Explain how knowing the frequency and severity of loss for a given exposure to loss is helpful in determining what should be done about that exposure.

4. Three rules of risk management proposed by Mehr and Hedges are discussed in this chapter. List these rules and explain the implications of each in determining what should be done about individual exposures facing a business firm.

5. Identify three categories into which insurance coverages may be priority ranked, indicating the nature of the exposures or risks to which each applies.

6. Describe the distinguishing characteristics of the risk retention groups and insurance-purchasing groups authorized by the Risk Retention Act of 1986.

7. Why is the decision to use risk control measures sometimes made on grounds other than the rules of risk management?

8. Distinguish between the cost of financing risk and the cost of financing losses.

9. Identify the reasons for self-insurance and the disadvantages of self-insurance.

10. Distinguish between pure captives and group association captives.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. The rules of risk management appear to be common sense. In view of this fact, how do you account for the widespread violation of these rules in insurance buying today?

2. Explain the relationship, if any, among the statements: “Don't risk more than you can afford to lose,” “Those people who need insurance most are those who can least afford it,” and “Insurance should be considered as a last resort.”

3. What are the implications of the observation that “the cause of a loss is less important than its effect?”

4. In what way does the cost of risk influence the decision to transfer or retain a particular risk?

5. In an effort to reduce insurance costs, the risk manager of a medium-sized manufacturing firm canceled the property insurance on the firm's $8.5 million plant and equipment, for which the annual premium was about $265,000. Two years later when the action was discovered, the risk manager was called on the carpet by a horrified vice president of finance. “What were you thinking of?” demanded the VP. “What if we had had a loss?” “But,” responded the risk manager, “we didn't have a loss. The fact that I saved the firm over half a million dollars in the past two years is proof that the decision was the right one.” If you agree with the risk manager, help her convince the VP she is right. If you disagree, help the VP convince the risk manager she is wrong.

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Denenberg, Herbert S. “Is A-Plus Really a Passing Grade?” Journal of Risk and Insurance, vol. 34, no. 3 (Sept. 1967).

Doherty, Neil A. Integrated Risk Management: Techniques and Strategies for Managing Corporate Risk. New York: McGrawHill, 2000.

Elliot, Michael W. Risk Management Principles and Practices. The Institutes, 2012.

Grose, Vernon L. Managing Risk: Systematic Loss Prevention for Executives Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1996.

Harrington, Scott E., and Gregory R. Niehaus. Risk Management and Insurance. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Mehr, R. I., and B. A. Hedges. Risk Management in the Business Enterprise. (Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin), 1963. Chapters 5–9.

Vaughan, Emmett J. Risk Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997.

Williams, C. Arthur, Peter C. Young, and Michael Smith. Risk Management and Insurance. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| A. M. Best Company | www.ambest.com |

| Captive Insurance Companies Association | www.cicaworld.com |

| Fitch, Inc. | www.fitchratings.com |

| International Risk Management Institute, Inc. | www.irmi.com |

| Moody's Investors Service | www.moodys.com |

| Nonprofit Risk Management Center | www.nonprofitrisk.org |

| Practical Risk Management | www.pracrisk.com/ |

| Public Agency Risk Managers Association (PARMA) | www.parma.com |

| Public Risk Management Association | www.primacentral.org |

| Risk and Insurance Management Society, Inc. | www.rims.org |

| RiskINFO | www.riskinfo.com/ |

| Self Insurance Institute of America | www.siia.org |

| Standard and Poor's Insurance Rating Services | www.standardandpoors.com/ |

| Weiss Ratings | www.weissratings.com |

![]()

1For example, see Mark R. Greene and Oscar N. Serbein, Risk Management: Text and Cases (Reston, Virginia: Reston Publishing Company, 1983), p. 52.

2The seminal article on utility and choices involving risk was written to provide a theoretical explanation for the apparent inconsistencies in human behavior with respect to risk. Some people will purchase insurance, indicating a distaste for uncertainty, while other people gamble, indicating that they prefer risk to certainty. To explain this anomaly, Friedman and Savage hypothesized that people who buy insurance have a different utility curve from that of gamblers. See Milton Friedman and L. J. Savage, “Utility Analysis of Choices Involving Risk,” Journal of Political Economy, LVI (August 1948), pp. 279–304.

3Ian Hacking, The Emergency of Probability: A Philosophical Study of Early Ideas about Probability, Induction, and Statistical Inherence London: Cambridge University Press, 1975, p. 62.

4This discussion of Pascal's wager is based on a discussion in Peter L. Bernstein, Against the Gods—The Remarkable Story of Risk (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1998), pp. 69–71.

5These rules appeared in the first edition of Robert I. Mehr and Bob A. Hedges, Risk Management in the Business Enterprise (Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin, 1963), pp. 16–26.

6Decisions with respect to loss prevention in connection with employee injuries have been greatly affected by the OSHA. The Williams-Steiger Act of 1970, better known as the Occupational Safety and Health Act, established a new agency within the U.S. Department of Labor, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which is empowered to set and enforce health and safety standards for almost all private employers in the nation. There are mandatory penalties under the law, ranging up to $7,000 for each violation. In addition, an employer who willfully or repeatedly breaks the law is subject to penalties ranging from $5,000 to $70,000 for each violation. Penalties may be assessed for every day that an employer fails to correct a violation during a period set in a citation from OSHA. Any willful violation of standards resulting in an employee's death, upon conviction, is punishable by a fine of up to six months' imprisonment or $10,000. The penalty for assaulting, interfering with, or resisting an OSHA inspector in the performance of his or her duties is imprisonment for up to three years and a fine of up to $5,000.

7If the firm decides that it will not maintain a reserve but will borrow the required $980,000 if a total loss occurs, the net effect is the same since it will need to maintain $980,000 of its line of credit free for use in the event of a loss. The opportunity cost is the same in either case.

8Unlike for the business firm, insurance premiums are not a tax-deductible expenditure for the individual. In addition, casualty losses sustained by an individual are deductible only to the extent that each loss exceeds $100 and the aggregate for all excess losses exceeds 10 percent of the individual's adjusted gross income.

9Most insurers advertise their ratings on their Web sites or marketing materials. Ratings are also available from the ratings agencies.

10See Herbert S. Denenberg, “Is A Plus' Really a Passing Grade?” The Journal of Risk and Insurance, vol. 34 (September 1967).

11Joseph M. Belth, “Financial Strength Ratings of Life-Health Insurance Companies,” The Insurance Forum, vol. 21, nos. 3 and 4 (March/April 1994), p. 15.

12See http://www.naic.org/cis/. The NAIC's Consumer Information Source provides information on the states in which an insurer is licensed, complaints that have been made against the insurer, and a brief summary of the insurer's financial profile.

13Some state insurance departments provide premium comparison information. Although this can be a useful starting place, the information does not always reflect the most current rates.

14For example, in 1999, the owner of Tokyo Disneyland issued catastrophe bonds (cat bonds) to cover its exposure to loss from earthquake. More recently, in 2006, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) issued a cat bond to protect itself against a terrorism-related cancellation of the 2006 World Cup in Germany, and Mexico issued a bond to cover earthquake losses. Cat bonds are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.

15Many state laws, for example, refer to the “self-insurance” of the workers compensation exposure, usually under conditions that do not contemplate any of the requirements specified by textbook writers.

16Under this definition, Caterpillar Insurance Company, a subsidiary of Caterpillar, Inc., would not be considered a captive since it was not organized for the purpose of underwriting the exposures of its parent. Some pure captives have broadened into writing business of others and moved from captives to ordinary insurance subsidiaries.

17Colorado was the first state to enact legislation (in 1972) designed to encourage the formation of captives, reducing some of the stringent requirements normally applied to insurers in such areas as capitalization, rating, pool participation, and surplus. By 2013. Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia had passed captive laws. Vermont has been the most successful in the U.S. Of the approximately 6,000 captives at the end of 2012, 856 were domiciled in Bermuda, 741 in the Cayman Islands, and 586 in Vermont.

18The IRS reversal was motivated by a court ruling in the 1989 Humana case, which made a distinction between premiums paid by the parent of a captive insurance company and those paid by brother/.sister companies. The court found that risk transfer did not occur with brother/sister companies. Humana, Inc. v. Commissioner, 881 F.2d 247, 257 (6th Cir. 1989).

19See Harper v. Commissioner, 979 F.2d 1341 (9th Cir. 1992).

20Internal Revenue Code Section 4371 assesses a 4 percent tax on premiums (except life insurance) written directly with a foreign insurer and a 1 percent tax on reinsurance premiums placed with a foreign insurer.

21The laws in nearly all states currently permit public bodies such as municipalities and counties to form self-insurance or risk-sharing pools. The pools are generally deemed not to be insurance companies and are not subject to the provisions of the state's insurance laws except as specifically provided by the statutes under which they are organized.