Chapter 18

Rules, Rules Everywhere: Government and Managerial Decision-Making

In This Chapter

![]() Including externalities

Including externalities

![]() Getting something for nothing as a free rider

Getting something for nothing as a free rider

![]() Using government to provide goods

Using government to provide goods

![]() Eliminating monopoly efficiency

Eliminating monopoly efficiency

![]() Regulating or preventing collusion

Regulating or preventing collusion

![]() Providing information equality

Providing information equality

![]() Restricting foreign competition

Restricting foreign competition

The United States relies primarily upon a system of markets and prices for resource and commodity allocation. But remember, markets are a means, not an end. Ultimately, the goal is to produce as much stuff as possible with those resources. In some instances, markets don’t work very well at producing and allocating stuff. In these instances, government can step in to improve the situation. The purpose of government intervention isn’t to preserve competition, but rather to ensure an efficient allocation of resources or provide goods the market wouldn’t necessarily provide on its own. Too often, however, the focus of regulation has been on competition, not efficiency.

Government intervention has always existed to varying degrees. In its early history, the United States regulated some areas of business by issuing licenses and, in the case of monopolies, fixing prices. For example, in his book Notes on the State of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson indicates that licensing and rate fixing were used with ferries.

During the last third of the 19th century, the rise of big business led to concerns regarding the power of business over consumers. Railroads represented the most extreme situation. Railroads often built lines parallel to one another to engage in rate wars and takeovers — for an example, see Chapter 14. At other times, railroads with monopolies in specific areas would charge extremely high rates. As a consequence, consumers, especially farmers, protested railroad rate setting. In Munn v. Illinois, the Supreme Court established that railroads were subject to government regulation. Ultimately, Court decisions led to the establishment of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1887. Within several years, government regulation of big business was extended through the Sherman Antitrust Act. So, government regulation has been around a long time and affects businesses in a lot of different ways.

In this chapter, I examine a few of the ways government intervention affects businesses. I give special attention to situations where markets don’t work very well. I begin by examining what happens when non-participants in a private market exchange incur costs or receive benefits — what economists call externalities. In some cases, external benefits lead to government, instead of private businesses, providing what are called public goods. Governments do regulate monopolies, and I examine monopoly regulation’s goal — just a hint, it’s not to have more competition. A brief overview of antitrust legislation and asymmetric information is then followed by government intervention in international trade.

Examining the Nature of Regulation

Resources are limited; thus the quantity of goods and services that society produces is limited. The goal of any economy is to satisfy as many consumer wants and desires as possible given this scarcity. In a market economy, these wants and desires are satisfied by the goods and services that profit-maximizing businesses provide.

Nevertheless, at times markets don’t work well — at times profit-maximizing behavior doesn’t lead to maximum satisfaction. In these situations or market failures, government regulation and intervention can improve upon the market outcome.

Working through Market Failures

Price represents the last unit of a good’s value to consumers, and marginal cost represents the cost of producing the last unit of a good. Markets are allocatively efficient when equilibrium results in the last unit’s price or value to consumers equaling the actual marginal cost of producing that unit. A market failure exists when price doesn’t equal marginal cost for the last unit produced. Market failures occur for a variety of reasons, including externalities (see the following section) and monopoly power (see Chapter 10 for details on monopoly).

Identifying Externalities

Externalities refer to beneficial or harmful effects realized by individuals or third parties who aren’t directly involved in the market exchange. Thus, an externality is a cost (in the case of a negative externality) or benefit (in the case of a positive externality) that is not reflected in the good’s price.

Producing too much with negative externalities: Pollution

Negative externalities result in social costs that are higher than the actual costs the firm pays. As a consequence, firms produce a larger quantity of output than is socially optimal. Government regulation attempts to internalize those costs for the firm, resulting in production decisions that represent true resource costs.

As Chapter 2 explains, commodity supply describes the relationship between the good’s quantity supplied, and the price producers are willing to accept for that good. Therefore, because some costs are not paid by the producers when there are negative externalities, they are willing to accept a price that’s lower than would be necessary if all costs were included.

Figure 18-1 illustrates a perfectly competitive market. If there are no externalities, the equilibrium output level, QE, corresponding to the intersection of the demand and market supply curves, represents the socially optimal output level.

Figure 18-1: Negative externality.

However, when pollution or another negative externality is present, the market supply curve in Figure 18-1 doesn’t represent the good’s true production cost. The true cost is now represented by the supply curve that includes the externality. In this situation, the good’s social cost equals the firms’ marginal cost curves represented by the market supply plus the marginal cost of the negative externality. As a consequence, marginal social cost results in the true supply curve with the externality being higher than the market supply.

Assuming the demand curve remains the same, the market’s socially optimal output level is QS corresponding to the intersection of demand and the supply curve with externality. The corresponding price consumers pay to cover the full cost of production is PS.

The purpose of government regulation is to reduce the market output from QE to the socially optimal level, QS. In order to accomplish this goal, government must internalize the cost of the negative externality for the firm. This is accomplished through various methods, such as fines, regulations requiring different production techniques, or taxes.

Producing too little with positive externalities: Honey

While negative externalities result in social costs that are greater than the actual costs paid by the firm, positive externalities exist when individuals receive uncompensated benefits through somebody else’s consumption of the good. Positive externalities result in firms producing a smaller quantity of output than is socially optimal. Government regulation attempts to compensate firms for those benefits, resulting in production decisions that recognize the good’s true value to society.

Commodity demand describes the relationship between the good’s quantity demanded and the price consumers are willing and able to pay for the good. Therefore, price represents the value of an additional unit of the good to consumers. However, if other individuals receive benefits — even though they aren’t part of the market transaction — those benefits aren’t included in the demand curve the firm faces.

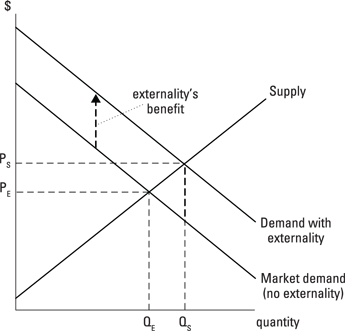

Figure 18-2 illustrates a perfectly competitive market with a positive externality. If there are no externalities, the equilibrium output level, QE, and price, PE, corresponding to the intersection of the market demand curve and supply curve represents the socially optimal output level.

Figure 18-2: Positive externality.

The presence of a positive externality, however, means the market demand curve doesn’t represent the good’s true value to society. With a positive externality, the true demand is higher than the market demand. This higher demand incorporates the added benefit or value of the positive externality. The resulting socially optimal output level corresponds to the intersection of the new demand curve with the positive externality and the market supply curve resulting in the socially optimal quantity QS and price PS.

Government intervention seeks to increase the market output to the socially optimal level. In order to accomplish this task, government may subsidize the producer to reflect the positive externality. In the case of honey, government may place a tax on plants and seeds and use the tax revenue to pay beekeepers a subsidy based on how many beehives they have. With the subsidy, beekeepers have an incentive to have more hives and bees.

Providing Public Goods: Free Riders

Public goods are goods that benefit individuals other than those involved in the market transaction. The consumption of public goods is nonrival and nonexclusionary. Nonrival means that the good’s consumption by one person doesn’t affect others consuming it. For example, when I listen to a radio broadcast, it doesn’t affect your ability to listen to the same broadcast. Nonexclusionary means that after the good is provided, no one can be excluded from consuming it. For example, clean air is nonexclusionary. Because public goods are nonrival and nonexclusionary, private firms can’t profitably provide them.

Given you’re able to consume a public good after it’s provided, you have little incentive to pay for it. A free rider is someone who enjoys the benefits of the good without paying for those benefits. If everyone acts as a free rider, private businesses can’t profitably provide a good.

The free riding problem results in government providing these goods and financing them through taxes. Taxes compel everyone to pay for the benefits they receive. But because taxes are a lump sum and voters typically don’t directly connect the cost of a specific item to its benefit, there is a tendency for public goods to be overproduced.

Regulating Monopoly

Chapter 10 examines profit-maximizing behavior for monopolies. As that chapter stresses, a monopolist’s ability to set price is constrained by consumer demand. If the monopolist tries to raise price too high, you’ll stop buying the product, or at the very least buy less of it.

In spite of this constraint, government still restricts the ability of many monopolies to set price. These restrictions are often described as “protecting” consumer interests, but more accurately, the restrictions lead to greater efficiency.

Losing through deadweight loss

Markets characterized by substantial economies of scale are typically better served by a monopoly rather than a large number of competitive firms. Figure 18-3 illustrates the production and pricing decisions for an unregulated monopolist with substantial economies of scale.

Figure 18-3: Unregulated natural monopoly.

The natural monopolist’s profit-maximizing quantity, q0, in Figure 18-3 corresponds to the intersection of marginal revenue and marginal cost. To determine price, the monopolist goes from q0 up to the demand curve — hence the constraint of consumer demand — and across to P0. Because price is greater than average total cost (ATC0) at q0, the monopolist earns positive economic profit per unit, π/unit.

This profit-maximizing solution results in a deadweight loss to society. The deadweight loss represents society’s welfare loss because the price P0 of the last unit, or the last unit’s value to a consumer, is greater than the marginal cost MC0, the cost of producing that unit. The deadweight loss corresponds to the shaded triangle in Figure 18-3.

Regulating for efficiency

Monopoly regulation’s purpose is to induce the monopolist to produce the socially optimal output level. In Figure 18-4, this is accomplished by government establishing a price, pR, that corresponds to the point where marginal cost intersects demand. Establishing a price through regulation results in the firm’s marginal revenue corresponding to that price. Marginal revenue corresponds to price because the monopolist charges the same price established by the regulators for every unit of the good it sells. After PR hits the demand curve, the monopolist must lower price to sell more units; therefore, marginal revenue develops a disjointed or vertical region at that output. The regulated monopoly’s marginal revenue curve is MRR.

Figure 18-4: Regulated natural monopoly.

The regulated monopolist maximizes profit by producing the output level associated with marginal revenue equals marginal cost. This output level is the socially optimal output level, qS.

Regulating for a fair return

In Figure 18-4, regulating for the socially optimal quantity of the good results in the monopoly shutting down in the long run. In order to avoid this situation, regulators often set price to guarantee that the monopolist receives a fair return. A fair return is zero economic profit or the firm’s owners earning exactly as much as they could in their next best alternative. Accountants might call this a normal return.

In fair-return pricing, regulators establish a price that corresponds to the output level where demand intersects average total cost. In Figure 18-4, this is the price PF. Once again, the monopoly must sell every unit it produces at the price regulators establish, so PF is the monopoly’s marginal revenue curve until it reaches the demand curve. After PF hits the demand curve, the monopolist must lower price to sell more units; therefore, marginal revenue again develops a disjointed or vertical region.

The monopoly produces the profit-maximizing quantity of output associated with marginal revenue intersects marginal cost, or the output level qF in Figure 18-4. Setting price at this level results in zero economic profit because price equals average total cost.

Restricting Interaction with Antitrust

With the rise of big business during the last third of the 19th century, laws were passed to encourage competition and prevent the concentration of economic power or monopoly. Continuing into the first half of the 20th century, additional legislation was passed to close loopholes or extend legislation into areas previously not covered. The legislations’ intent is to prevent practices that reduce competition rather than lower costs through improved operating efficiency.

Prohibiting collusion

The first antitrust law passed was the Sherman Act in 1890. Its two major provisions state the following:

![]() “Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is hereby declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any such contract or engage in any such combination or conspiracy, shall be deemed guilty of a felony.”

“Every contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations, is hereby declared to be illegal. Every person who shall make any such contract or engage in any such combination or conspiracy, shall be deemed guilty of a felony.”

![]() “Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony.”

“Every person who shall monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among several States, or with foreign nations, shall be deemed guilty of a felony.”

The Sherman Act prevents executives representing rival firms from working together to reduce competition. For example, executives in the same industry can’t discuss prices or agree to fix them.

Although it reduces anticompetitive practices, the Sherman Act doesn’t cover all such practices. In addition, the Act is often regarded as too vague. These difficulties led to the passage of additional legislation.

In 1914, the federal government passed additional legislation supporting competition by addressing weaknesses in the Sherman Act. The Clayton Act prohibits price discrimination, tying contracts, and intercorporate stock holdings if they substantially reduce competitive practices. Section 2 of the Clayton Act prohibits price discrimination unless cost differentials in serving various customers justify the price differentials or the lower prices charged in certain markets are established to meet the competition in that area. Tying contracts require a firm purchasing one item to purchase other items. Section 3 of the Clayton Act prohibits tying contracts that reduce competition.

The Federal Trade Commission Act, also passed in 1914, prohibits unfair competitive practices and created the Federal Trade Commission to prosecute antitrust violations and to protect the public from false and misleading advertisements. Additional legislation directed at preserving competition includes the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936. This act prevents large-scale retailers from engaging in unfair price cutting in order to drive smaller retailers out of business.

The enforcement of antitrust legislation is the responsibility of the antitrust division of the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission. Antitrust violations are resolved by dissolution and divestiture, injunction, and consent decree. In addition, fines and jail sentences can be imposed.

The Supreme Court usually enforces provisions of the Sherman Act that prevent the formation of cartels or informal collusion that results in price fixing, price leadership schemes, or market sharing. In addition, the Supreme Court prevents predatory pricing (selling a product below average variable cost in order to drive out rival firms) and other price behavior, such as price discrimination, that reduces competition.

Preventing mergers

Antitrust legislation is frequently applied to corporate mergers. The following are the three types of mergers:

![]() A horizontal merger occurs between firms that are direct competitors in the same product market. An example of a horizontal merger is two firms producing laundry detergent merging.

A horizontal merger occurs between firms that are direct competitors in the same product market. An example of a horizontal merger is two firms producing laundry detergent merging.

![]() A vertical merger occurs between a firm and its suppliers, or between different firms associated with different stages of the good’s production process. An example is a merger between a coal and steel company.

A vertical merger occurs between a firm and its suppliers, or between different firms associated with different stages of the good’s production process. An example is a merger between a coal and steel company.

![]() A conglomerate merger occurs between firms in completely unrelated lines of production. A merger between a firm providing financial services and a firm operating a chain of retail stores is an example of a conglomerate merger.

A conglomerate merger occurs between firms in completely unrelated lines of production. A merger between a firm providing financial services and a firm operating a chain of retail stores is an example of a conglomerate merger.

Section 7 of the Clayton Act prevents a firm from acquiring the stock of a rival firm if it reduces competition. The Celler-Kefauver Antimerger Act of 1950 extends the intent of Section 7 of the Clayton Act by making it illegal to acquire the assets of competing corporations if such an action results in a substantial reduction in competition or creates a monopoly. As a result, such mergers require government approval to determine whether or not there is a substantial reduction in competition.

Generally, the Supreme Court upholds antitrust prosecution of horizontal mergers between large, direct competitors. In the absence of a substantial increase in horizontal market power, vertical and conglomerate mergers typically don’t result in antitrust violations.

Regulating Information Asymmetry: I Know Something You Don’t Know

As Chapter 17 explains, information asymmetry refers to market situations where some participants have better information than other participants. Participants with better information are at a competitive advantage to those with less information. After rational individuals with less information recognize the situation, they will choose not to participate. As a result, there are fewer, perhaps no, market transactions when information asymmetry persists.

One of the most important areas of asymmetric information is in the buying and selling of stocks. Legislation restricting insider trading prevents company officials from acting on information that isn’t publically known. For example, a company engaging in promising pharmaceutical research knows that the Food and Drug Administration has decided not to approve one of its previously promising drugs. An insider possessing this information before it’s made public can sell the company’s stock today at a high price before the price drops after the announcement. Purchasers end up losing money because they didn’t possess the insider information. Over time, outsiders become very reluctant to trade the firm’s stock because they fear others know something they don’t.

By regulating insider trading through the Securities and Exchange Commission, the government supports an efficient market for stocks and bonds. Participants in the market, both buyers and sellers, know that the information behind the decisions to buy and sell stocks and bonds is accessible to everyone.

Government also regulates advertising to ensure claims are valid. Businesses have more information about the goods they produce than consumers. It’s difficult for consumers to independently test the claims. The Lanham Act prohibits false and misleading advertising. Similarly, restaurant and public health inspections help insure health standards are maintained.

Yet another area of information asymmetry that government regulates is lending. The Truth in Lending Simplification Act requires creditors to make written declaration of important information including the annual interest rate, itemized finance charges, and the total purchase price.

As these areas illustrate, government attempts to reduce information asymmetry by requiring all parties to a transaction to fully disclose pertinent information. This asymmetry reduction facilitates market exchange by reducing the likelihood that individuals stop participating in the market because they have less information.

Determining Who’s in Business by Licensing Providers

As a doctor, I’m ready to address any and all of your physical ailments. And just in case you hesitate, I do have a degree that says I’m a doctor — not a medical doctor but a doctorate in economics. Thus, if you have a sore back, you shouldn’t see me, but if you have a sore bottom line, perhaps I can help.

This situation illustrates another important area of information asymmetry — how to assess professional expertise. I’m quite incapable of determining whether or not an individual possesses sufficient knowledge to care for my physical health. Thus, I require somebody with that expertise to make the judgment on my behalf.

Through licensure, the government relies on experts to evaluate a peer’s credentials. Upon satisfactory completion of the evaluation, the individual receives a license certifying that expertise. Engineers, accountants, lawyers, and medical doctors are among the many occupations that require licenses.

Understanding Government’s Role in International Trade

Consumers can purchase similar goods either produced domestically or internationally (imports). These imports are a major source of competition for domestic firms.

Charging tariffs

A tariff is a tax charged on imports. Government uses tariffs to protect domestic industries from foreign competition. As a result of a tariff, domestic firms typically are able to charge a higher price while also producing more output. In order to produce more output, it’s not uncommon for tariffs to lead to higher employment in protected industries as compared to the employment level that would exist if the industry were unprotected.

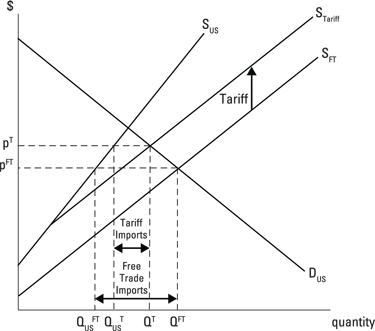

Figure 18-5 illustrates a protective tariff’s impact as compared to free trade. The underlying assumption for Figure 18-5 is that the United States government is imposing a tariff on imports in order to protect U.S. firms. The market illustrated in Figure 18-5 is the market for the good in the United States. Thus, the demand curve labeled DUS is the good’s demand from customers in the United States. The supply curve SUS is the U.S. supply curve and illustrates the quantity of the good U.S. firms are willing to produce and sell at various possible prices. The supply curve SFT is the world supply of the good to the U.S. market assuming free trade — no tariffs. The world’s supply includes the quantity U.S. firms are willing to produce plus the quantity foreign firms are willing to produce to sell in the U.S. market.

Figure 18-5: International trade with tariffs.

If free trade exists and the market is in equilibrium, the good’s equilibrium price is PFT, which corresponds to the intersection of DUS and SFT. The quantity of the good U.S. consumers purchase is QFT. The quantity of the good U.S. firms produce equals QUSFT. Given the good’s free-trade price PFT, this is the quantity U.S. firms are willing to provide based upon the U.S. supply curve SUS. The difference between the quantity purchased by U.S. consumers, QFT, and the quantity produced by U.S. firms, QUSFT, is made up with imports as labeled in Figure 18-5.

If U.S. firms are successful in lobbying the federal government for tariff protection, the world’s supply of the good to the U.S. market shifts to STariff. As illustrated on Figure 18-5, the vertical difference between the world supply curve with no tariffs, SFT, and the world supply curve with tariffs, STariff, represents the amount of the tariff as labeled. If the tariff is the same for each unit of the good imported, the vertical difference doesn’t change.

With a tariff in place, the market adjusts to a new equilibrium. The good’s equilibrium price increases to PT, which corresponds to the intersection of DUS and STariff. The quantity of the good U.S. consumers purchase is QT. The quantity of the good U.S. firms produce equals QUST. Given the good’s price with the tariff, PT, this is the quantity U.S. firms are willing to provide given the U.S. supply curve SUS. The difference between the quantity purchased by U.S. consumers, QT, and the quantity produced by U.S. firms, QUST, is made up with imports as labeled in Figure 18-5.

The tariff has the desired effect. It increases the price U.S. firms receive and, as a result, the firms increase their production from QUSFT to QUST. Not surprisingly, imports also shrink because the foreign firms have to subtract the tariff from the price they receive.

Restricting through quotas

Quotas restrict the quantity of imports from other countries. Quotas are another method government uses to protect domestic industries from foreign competition. Like a tariff, quotas lead to higher prices for domestic firms, which provides incentive to produce more output. Thus, quotas also lead to higher employment if an industry is protected for foreign competition.

Figure 18-6 illustrates an import quota’s impact as compared to free trade. Similar to Figure 18-5, Figure 18-6 assumes the United States government is imposing an import quota to protect U.S. firms. Figure 18-6 illustrates the good’s U.S. market. The demand curve labeled DUS is U.S. consumer demand for the good. The supply curve, SUS, is the U.S. supply curve and illustrates the quantity of the good U.S. firms are willing to produce and sell at various possible prices. The supply curve SFT is the world supply of the good to the U.S. market assuming free trade — no quotas or tariffs.

If free trade exists and the market is in equilibrium, the good’s equilibrium price and quantity are PFT and QFT as determined by the intersection of DUS and SFT. U.S. consumers purchase the quantity QFT. Given free trade, U.S. firms produce QUSFT — this is the quantity U.S. firms are willing to provide given where the good’s free trade price PFT hits the U.S. supply curve SUS. The difference between the quantity purchased by U.S. consumers, QFT, and the quantity produced by U.S. firms, QUSFT, is made up with imports as labeled in Figure 18-6.

Figure 18-6: International trade with quotas.

U.S. firms successfully lobby the federal government for an import quota. As a result, the world’s supply of the good to the U.S. market shifts to SQuota. As illustrated in Figure 18-6, the horizontal difference between the U.S. supply curve, SUS, and the world supply with the quota, SQuota, equals the quota. This is the maximum permitted quantity of imports. The quota’s impact on supply is illustrated in Figure 18-6.

A quota leads to a new market equilibrium. The good’s equilibrium price increases to PQ, which corresponds to the intersection of DUS and SQuota. U.S. consumers purchase QQ of the good. U.S. firms produce QUSQ — this is the quantity U.S. firms are willing to provide given the market price PQ and the U.S. supply curve SUS. The difference between the quantity purchased by U.S. consumers, QQ, and the quantity produced by U.S. firms, QUSQ, is made up with imports as labeled in Figure 18-6. Thus, imports equal the amount of the quota.

The quota accomplishes its intended goal by increasing the price U.S. firms receive. As a result, U.S. firms produce more — moving to QUSQ from QUSFT. This production increase may lead to higher employment in the protected industry. At the same time, imports decrease to the amount of the quota.

Other types of trade restrictions include embargos that prevent trade with another country and negative lists that exclude items from free trade agreements.

Getting Ahead through Rent Seeking

Free markets permit individuals to pursue their own interests. Thus, consumers seek goods that allow them to maximize their satisfaction given the constraint imposed by their income. Given that constraint, consumers naturally want the lowest possible prices. Business owners want to maximize their profit because that profit becomes income as they purchase goods and services. Not surprisingly, business owners want prices to be very high, resulting in more profit.

Usually, these different and conflicting motives aren’t a problem as Adam Smith recognized. Individuals are free to choose whether or not to buy and sell a good. Thus, given this freedom of choice, buyers and sellers engage in exchange only if it’s mutually beneficial. Government intervention can change this. Such intervention is especially important when markets fail. Government intervention improves resource allocation by influencing business behavior when there’s a market failure. But it’s also possible for government to implement policies that benefit some parties at the expense of others. Rent seeking occurs when an individual’s or group’s efforts to get government intervention benefits them at another individual’s or group’s expense. These rent-seeking efforts can lead to inefficiency. Examples of rent-seeking include political lobbying for government subsidies or using government-issued licenses to prevent competitors from entering a market.

An example of a negative externality is pollution. A fisherman who doesn’t consume a firm’s product experiences a negative externality if the firm’s pollution adversely affects fishing. The fisherman incurs a cost, although he’s not a consumer of that firm’s product.

An example of a negative externality is pollution. A fisherman who doesn’t consume a firm’s product experiences a negative externality if the firm’s pollution adversely affects fishing. The fisherman incurs a cost, although he’s not a consumer of that firm’s product.

This regulation is self-defeating. At the regulation’s profit-maximizing price

This regulation is self-defeating. At the regulation’s profit-maximizing price