Chapter 10

Monopoly: Decision-Making Without Rivals

In This Chapter

![]() Identifying the source of monopoly power

Identifying the source of monopoly power

![]() Separating demand and marginal revenue

Separating demand and marginal revenue

![]() Determining the profit-maximizing quantity and price

Determining the profit-maximizing quantity and price

![]() Minimizing cost with multiple factories

Minimizing cost with multiple factories

Parker Brothers’ popular board game Monopoly has it all wrong. The board game doesn’t describe monopoly at all. The board game has 22 properties — not counting railroads and utility companies — that you can buy, sell, and rent. That’s way too much competition. In the market structure of monopoly, there’s only one firm, and because a single firm produces the good, monopoly has a very low degree of competition. In fact, monopolists have no direct rivals.

This situation may give the misimpression that a monopolist has unlimited power. That isn’t the case. The monopolist is constrained by whether or not consumers are willing to buy the monopolist’s product at a given price. Also, a monopolist can face indirect competition from other firms that produce something that addresses the same needs. For example, the firm providing natural gas and the firm providing electricity are monopolies. As a consumer, you can choose either natural gas or electricity to operate your home’s oven and stove.

In this chapter, I start by examining monopoly characteristics and their impact on decision-making, especially price setting. These characteristics give the monopolist the ability to set price. After identifying the source of monopoly power, I summarize how a monopolist determines the short-run profit-maximizing quantity, price, and amount of profit by using two approaches — the first based on total revenue and total cost, and the second based on marginal revenue and marginal cost. After considering the short-run situation, I explain how things evolve in the long run. Finally, I conclude the chapter by examining how monopolies profitably produce the same good in two or more factories. And after you understand these concepts, you’ll feel like you own both Park Place and Boardwalk. Now, that’s a really profitable monopoly.

Standing Alone: Identifying the Sources of Monopoly Power

If you possess monopoly power, you’re able to set your good’s price. Thus, as manager, you must now determine both the profit-maximizing quantity of output and the good’s price. You really have to mind your p’s and q’s in monopoly.

Monopolies have the following characteristics:

![]() A single firm: Your firm is the only one that produces the good. Therefore, the entire quantity of the good sold in the market is produced by your firm.

A single firm: Your firm is the only one that produces the good. Therefore, the entire quantity of the good sold in the market is produced by your firm.

![]() No close substitutes: In addition to being the only firm producing the good, there are no close substitutes for the good you produce. No other firm provides a similar or directly substitutable good. As a consequence, no direct competition between firms exists.

No close substitutes: In addition to being the only firm producing the good, there are no close substitutes for the good you produce. No other firm provides a similar or directly substitutable good. As a consequence, no direct competition between firms exists.

![]() Barriers to entry: Barriers to entry ensure the continued existence of the monopoly. Barriers to entry also enable the monopolist to maintain positive economic profit, or returns in excess of the normal rate of return, in the long run. Barriers to entry can take many forms, including economies of scale, government regulation, patents, and control of specific natural resources.

Barriers to entry: Barriers to entry ensure the continued existence of the monopoly. Barriers to entry also enable the monopolist to maintain positive economic profit, or returns in excess of the normal rate of return, in the long run. Barriers to entry can take many forms, including economies of scale, government regulation, patents, and control of specific natural resources.

Because a single firm produces the good’s entire market output, the firm is a price setter — the monopolist determines the price it charges for the good. The demand for the monopolist’s product is the same as the market demand because only one firm is producing the good. However, this situation has its pros and cons. On the pro side, you get to set price, and you have no direct rivals. On the con side, if you want to sell more of the good, you have to lower price. In perfect competition (see Chapter 9), you could sell as much as you wanted without having to change price. This isn’t the case in monopoly.

The reason you have to lower price to sell more of the good is a monopolist’s ability to set price is constrained by consumer demand — consumers will buy more of the product only if you lower its price.

Also, the absence of close substitutes for the monopolist’s product ensures the monopolist’s ability to set price without direct competition. However, to the extent imperfect substitute goods exist, they influence consumer demand and the monopolist’s ability to set price. Therefore, the monopolist doesn’t take into account rival firm behavior when it determines its short-run profit-maximizing quantity and price. But over an extended period of time, or in the long run, the monopolist’s profits are affected by indirect competition.

Unable to Charge as Much as You Want: Relating Demand, Price, and Revenue

There is little doubt that monopoly has a bad reputation. At the word monopoly, consumers typically picture a large firm that charges any price it wants. It’s a firm with virtually unlimited power. But consumers are wrong!

The ultimate source of power in a market is the consumer. As a consumer, you get to decide whether you’re willing and able to purchase a good at a given price. In theory, the monopolist can charge any price it wants, but practically, the monopolist can’t charge too high of a price or you won’t buy the good. The monopolist is constrained by your willingness to pay the price it charges.

For example, economists consider De Beers a resource monopoly because it effectively controls the world’s supply of diamonds. And although diamonds are very popular, if De Beers keeps raising its price, consumers will start substituting other precious gems, such as rubies and emeralds, for diamonds. Thus, as diamond prices increase, the quantity of diamonds consumers purchase will decrease.

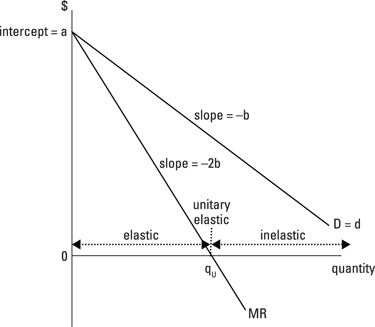

The inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded is the critical element in monopoly price setting. Because a single firm provides the entire quantity of the commodity in the market, the demand for the monopolist’s product, represented by a lower-case d in Figure 10-1, is the same as the market demand, represented by a capital D in Figure 10-1. The market demand possesses the usual characteristics; an inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded and changing price elasticity of demand along the demand curve. In order to sell more of its product, the monopolist must lower its price, not only for the additional unit but for every other unit as well.

Figure 10-1: The relationship between demand and marginal revenue.

Figure 10-1 also illustrates the relationship between a monopolist’s demand and marginal revenue. Remember that marginal revenue is the change in total revenue that occurs when one additional unit of a good is produced and sold. Because the monopolist’s demand curve is identical to the market demand curve, the monopolist can sell an additional unit of output only by lowering the product’s price. Assuming no price discrimination (charging different customers different prices for the same good), this lower price is charged for all units of the commodity sold. As a consequence, the firm’s marginal revenue curve lies below its demand curve. Marginal revenue is less than price.

Marginal revenue is related to the price elasticity of demand — the responsiveness of quantity demanded to a change in price. As I indicate in Chapter 4, when marginal revenue is positive, demand is elastic; and when marginal revenue is negative, demand is inelastic. The output level at which marginal revenue equals zero corresponds to unitary elasticity. This occurs at the quantity qu in Figure 10-1.

![]()

where P is the good’s price in dollars and q is the quantity demanded. Constants in the equation are represented by a and b — a is the intercept of the demand curve (where the demand curve intersects the vertical axis) and b is the demand curve’s slope.

Total revenue, TR, equals price times quantity or

![]()

Marginal revenue, MR, equals the derivative of total revenue taken with respect to quantity

![]()

If you compare the marginal revenue equation with the demand equation, you see that both equations have an intercept represented by a. The slope of the demand equation is represented by –b, while the slope of the marginal revenue equation is –2b. Thus, for a linear demand curve, the marginal revenue curve starts at the same intercept as the demand curve, but its slope is twice as steep. This is represented in Figure 10-1.

Engaging in Advertising and Non-Price Competition

Monopolists don’t have direct rivals. However, monopolists still have incentive to engage in advertising and other forms of non–price discrimination, such as innovation. Because the monopolist is constrained by consumer demand, anything that increases demand increases the monopolist’s revenues. Thus De Beers — who essentially monopolizes the market for diamonds — extensively advertises diamonds for special occasions in order to increase its demand. The result is that engagement rings have diamonds, although I prefer emeralds.

Maximizing Short-Run Profit

Like every other firm, regardless of how much competition exists in the market, the monopolist wants to maximize profit — the difference between its total revenue and total cost. Basic cost theory, as I describe in Chapter 8, isn’t affected by the amount of competition that exists. So what’s the big difference that more or less competition has on a firm? Competition affects the revenue side of the firm’s decision. In the case of monopoly, the market demand is the same as the firm’s demand, and marginal revenue lies below the demand curve. This is the critical difference in monopoly as compared to other markets with a higher degree of competition.

Maximizing profit with total revenue and total cost

Total profit equals total revenue minus total cost. In order to maximize total profit, you must maximize the difference between total revenue and total cost. The first thing to do is determine the profit-maximizing quantity. Substituting this quantity into the demand equation enables you to determine the good’s price. Alternatively, dividing total revenue by quantity enables you to determine price.

Graphically, the total revenue and total cost curves appear as illustrated in Figure 10-2. The total revenue curve increases but at a decreasing rate — the curve becomes flatter. Eventually, total revenue begins to decrease. This relationship between total revenue and quantity reflects the fact that as a monopolist, you need to charge a lower price in order to sell more output. The lower price leads to smaller increases and eventually decreases in total revenue.

Figure 10-2: Profit maximization with total revenue and total cost.

The nonlinear relationship, or increasing at a decreasing rate, also reflects the changing price elasticity of demand along the demand curve. The region where total revenue is increasing corresponds to the elastic region of the market demand curve. In Figure 10-1, this is the region where marginal revenue is greater than zero, and thus total revenue is increasing. Decreasing total revenue as output increases reflects the inelastic region of market demand where marginal revenue is negative. Producing more in this region means less revenue because in order to sell more of the good you have to lower price on every unit you sell. The lower price on every other unit you sell decreases your revenue by more than you gain through the one extra unit you’re now able to sell. The point where total revenue is maximized corresponds to unitary elasticity. This is the point where marginal revenue equals zero in Figure 10-1.

Remember that even when you produce nothing in the short run, you’re stuck with fixed costs. So at zero units of output, the monopoly’s total fixed cost equals TFC in Figure 10-2. As the quantity of output produced increases, total cost initially increases at a decreasing rate. This situation occurs until diminishing returns begin. After diminishing returns start — and they must start at some point — total cost increases at an increasing rate. That is, the total cost curve becomes steeper, as illustrated in Figure 10-2.

Total profit is represented by the vertical difference between the total revenue and total cost curves. The monopolist determines the output level at which total profit is maximized or the difference between total revenue and total cost is greatest. In Figure 10-2 this corresponds to q0 of output. At q0, your total revenue equals TR0 and your total cost equals TC0. Your total profit equals total revenue minus total cost and is represented by the double-headed arrow labeled π in Figure 10-2.

Deriving maximum profit with derivatives

You can use calculus to maximize the total profit equation. Because total revenue and total cost are both expressed as a function of quantity, you determine the profit-maximizing quantity of output by taking the derivative of the total profit equation with respect to quantity, setting the derivative equal to zero, and solving for the quantity.

![]()

where q is the market and firm’s quantity demanded, and P is the market price in dollars.

Using the demand equation to derive total revenue as a function of q requires the following steps:

1. Add 200P to both sides of the demand equation.

![]()

2. Subtract q from both sides of the equation.

![]()

3. Divide both sides of the equation by 200.

![]()

4. To determine total revenue, multiply both sides of the demand equation by q.

![]()

This equation tells you how much total revenue equals given any value for quantity, q. Thus, total revenue is a function of q.

If your total cost equation is

![]()

total profit, π, is determined by subtracting total cost from total revenue, or

![]()

After you have the total profit equation, the following steps enable you to determine the profit-maximizing quantity and price:

1. Take the derivative of the total profit equation with respect to quantity.

![]()

2. Set the derivative equal to zero and solve for q.

This is your profit-maximizing quantity of output.

![]()

3. Substitute the profit-maximizing quantity of 2,000 into the demand equation and solve for P.

![]()

Or you should set a price of $40 for the good.

4. Finally, total profit is determined by substituting 2,000 for q in the total-profit equation.

![]()

Your total profit equals $18,000.

Maximizing profit with a marginally better method

Quite often it’s easier to determine the profit-maximizing quantity of output by focusing on the last unit you produce, or the marginal unit. In order to add to your profit, an additional or marginal unit of the good must add more to your revenue than it adds to your cost. In other words, marginal revenue is greater than marginal cost. As long as an additional unit adds more to your revenue than it adds to your cost, your profit is increasing. At the output level that maximizes profit, an additional unit of output doesn’t add any more to your total profit. This occurs when marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Stop at this output level because if you go beyond this point and continue to produce more, marginal cost is greater than marginal revenue — so you’re adding more to your cost than you’re adding to your revenue, and your total profit is decreasing.

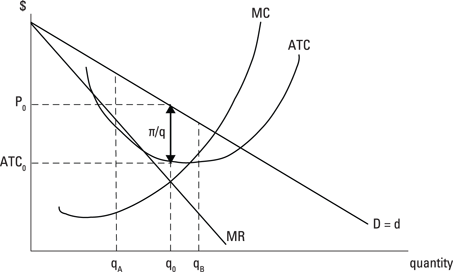

In Figure 10-3, the monopolist’s downward-sloping demand curve d is the same as the market demand curve D, or D = d. As previously described in the section “Unable to Charge as Much as You Want: Relating Demand, Price, and Revenue,” given the linear demand curve, the marginal revenue curve has the same intercept on the vertical axis and is twice as steep as the demand curve. Marginal revenue is represented by the curve labeled MR.

Figure 10-3: Profit maximization with marginal revenue and marginal cost.

Marginal cost, MC, is upward-sloping and passes through the minimum point on average total cost, ATC.

To maximize profits, you produce the output level associated with marginal revenue equals marginal cost, or the output level q0 that corresponds to the point where the marginal revenue and marginal cost curves intersect.

To find the price you charge, go from the profit-maximizing quantity of output, up to the demand curve and across. The profit-maximizing price corresponds to P0.

If you produce less than q0 output, for example qA, those units still add more to your revenue than they add to your cost. For those units, marginal revenue is greater than marginal cost. You increase profits by producing more output moving toward q0.

If you produce output beyond q0, such as qB, those units add more to your cost than they add to your revenue because marginal cost is greater than marginal revenue. These units reduce your profit so you should cut back production to q0.

As is the case for any firm, a monopolist determines profit per unit by subtracting average total cost from price. In Figure 10-3, profit per unit is represented by the double-headed arrow labeled π/q. Total profit is determined by multiplying profit per unit by the number of units sold, q0.

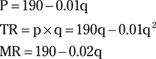

Maximizing profit with calculus

Figure 10-3 indicates that profit is maximized at the quantity of output where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Marginal revenue represents the change in total revenue associated with an additional unit of output, and marginal cost is the change in total cost for an additional unit of output. Therefore, both marginal revenue and marginal cost represent derivatives of the total revenue and total cost functions, respectively. You can use calculus to determine marginal revenue and marginal cost; setting them equal to one another maximizes total profit.

![]()

generated the total revenue equation.

![]()

Also assume your total cost equation is

![]()

Given these equations, the profit-maximizing quantity of output is determined through the following steps:

1. Determine marginal revenue by taking the derivative of total revenue with respect to quantity.

![]()

2. Determine marginal cost by taking the derivative of total cost with respect to quantity.

![]()

3. Set marginal revenue equal to marginal cost and solve for q.

![]()

4. Substituting 2,000 for q in the demand equation enables you to determine price.

![]()

Thus, the profit-maximizing quantity is 2,000 units and the price is $40 per unit.

Calculating economic profit and the profit-per-unit fallacy

Economic profit per unit equals price minus average total cost, or

![]()

In Figure 10-3, economic profit per unit is illustrated by the double-headed arrow labeled π/q.

Total profit equals profit per unit multiplied by the number of units sold, or

![]()

![]()

And the monopolist’s total cost equation is

![]()

Given this information, the profit-maximizing quantity is 2,000 units at a price of $40 per unit.

In order to determine the monopolist’s economic profit per unit and total profit, you take the following steps:

1. Determine the average total cost equation by dividing the total cost equation by the quantity of output q.

![]()

2. Substitute q equals 2,000 in order to determine average total cost at the profit-maximizing quantity of output.

![]()

Thus, the average total cost is $31 at the profit-maximizing quantity of 2,000 units.

3. Calculate profit per unit.

![]()

Profit per unit equals $9.

4. Determine total profit by multiplying profit per unit by the profit-maximizing quantity of output.

![]()

Total profit equals $18,000.

![]()

On the other hand, if your profit per unit is only $9 but you’re now able to sell 2,000 units because you charge a lower price, your total profit equals $18,000.

![]()

Remember, your goal is always to maximize total profit.

Minimizing losses to make the best of a bad situation

In the short run, monopolies can incur economic losses. In the case of economic losses, the price associated with the marginal revenue equals marginal cost output level is less than average total cost. Figure 10-4 indicates a situation where the monopoly earns negative economic profit.

Figure 10-4: Producing with economic losses.

In Figure 10-4, note the monopolist’s demand and marginal revenue curves have the same shape as in situations I describe earlier in this chapter. The demand curve is downward-sloping, indicating that the monopolist must lower price to sell a greater quantity of output, and marginal revenue lies below the demand curve. Average total cost, average variable cost, and marginal cost all have the usual shapes. Marginal cost is upward-sloping, reflecting diminishing returns. Average variable cost and average total cost are both U-shaped, and marginal cost passes through the minimum point on both curves.

Given its demand curve and cost curves, this monopolist maximizes profits — minimizes losses — by producing the quantity of output q0 that corresponds to the intersection of marginal revenue and marginal cost. Price is determined by going from q0 up to the demand curve and across to P0.

The firm’s economic loss equals the difference between price and average total cost. It’s a loss because price is less than average total cost, so

![]()

The loss per unit is represented by the double-headed arrow labeled –π/q in Figure 10-4.

Shutting down

In the short run, if you immediately shut down, you still lose money because of your fixed costs. Shutting down means you produce zero output, earn zero revenue, and incur zero variable costs. However, because you can’t change your fixed inputs, you still have fixed costs. Thus, your short-run losses equal total fixed cost.

In order for an immediate shutdown to make sense, the shutdown has to maximize profits, or, in this case, minimize losses. For that to happen, the economic losses resulting from the production of the output level associated with marginal revenue equals marginal cost are greater than total fixed costs. This is the case if the price determined off the demand curve is less than your average variable cost. Thus, you should immediately shut down if the profit-maximizing price is less than average variable cost. If price is less than average variable cost, you not only lose fixed costs, you’re not even able to pay all your variable costs.

Anticipating the Long Run

The long run allows you to change any input — fixed inputs don’t exist in the long run. But the long run also usually allows other firms to enter profitable markets. However, this doesn’t happen in monopolistic markets due to barriers to entry.

Keeping others out with barriers to entry

A critical characteristic of monopoly is the presence of barriers to entry. However, different barriers to entry exist. The different barriers to entry lead to different types of monopoly.

![]() Natural Monopoly: Natural monopolies exist due to economies of scale. As the consequence of the economies of scale, the monopoly provides the commodity at much lower cost per unit than potential entrants, discouraging new firms from establishing themselves in the market. Electric companies are an example of a natural monopoly.

Natural Monopoly: Natural monopolies exist due to economies of scale. As the consequence of the economies of scale, the monopoly provides the commodity at much lower cost per unit than potential entrants, discouraging new firms from establishing themselves in the market. Electric companies are an example of a natural monopoly.

![]() Legal Monopoly: Legal monopolies exist due to government legislation and protection. Typically, legal monopolies are privately-owned companies that are granted a monopoly by the government. The legal monopoly is established to protect consumers’ interests. An example of a legal monopoly is local cable television service. In this situation, a local government grants a monopoly in order to eliminate unnecessary duplication of costs that leads to higher prices for customers. For example, two cable television companies have to lay twice as much cable, construct two transmission facilities, and so on. The consequence is a doubling in cost. In addition, these two companies would split the market, resulting in each company serving half as many customers as a monopolist. The inevitable result is higher prices for consumers.

Legal Monopoly: Legal monopolies exist due to government legislation and protection. Typically, legal monopolies are privately-owned companies that are granted a monopoly by the government. The legal monopoly is established to protect consumers’ interests. An example of a legal monopoly is local cable television service. In this situation, a local government grants a monopoly in order to eliminate unnecessary duplication of costs that leads to higher prices for customers. For example, two cable television companies have to lay twice as much cable, construct two transmission facilities, and so on. The consequence is a doubling in cost. In addition, these two companies would split the market, resulting in each company serving half as many customers as a monopolist. The inevitable result is higher prices for consumers.

![]() Government Monopoly: A government monopoly is a monopoly that’s owned and operated by government. The primary difference between a government monopoly and a legal monopoly is that the government monopoly is publicly owned while the legal monopoly is privately owned. Examples of government monopolies include garbage collection in some cities and public water companies.

Government Monopoly: A government monopoly is a monopoly that’s owned and operated by government. The primary difference between a government monopoly and a legal monopoly is that the government monopoly is publicly owned while the legal monopoly is privately owned. Examples of government monopolies include garbage collection in some cities and public water companies.

![]() Patent Monopoly: Protection of an invention under the patent laws results in a patent monopoly. This protection’s purpose is to encourage research and development by ensuring a period of time over which the potential for monopoly profit exists. Such protection, however, is temporary; therefore, patent monopolies have a limited lifespan as a monopoly. Examples of patent monopolies are numerous, ranging from Xerox’s patents on components of copying technology to Lego’s patent on the interlocking feature of plastic toy building blocks.

Patent Monopoly: Protection of an invention under the patent laws results in a patent monopoly. This protection’s purpose is to encourage research and development by ensuring a period of time over which the potential for monopoly profit exists. Such protection, however, is temporary; therefore, patent monopolies have a limited lifespan as a monopoly. Examples of patent monopolies are numerous, ranging from Xerox’s patents on components of copying technology to Lego’s patent on the interlocking feature of plastic toy building blocks.

![]() Resource Monopoly: A single firm’s virtual control of an entire resource’s supply results in a resource monopoly. The best current example of a resource monopoly is De Beers’s control of diamonds.

Resource Monopoly: A single firm’s virtual control of an entire resource’s supply results in a resource monopoly. The best current example of a resource monopoly is De Beers’s control of diamonds.

Enjoying the long run

Because of barriers to entry, monopolies are able to maintain positive economic profit in the long run. Therefore, the conditions of the short-run equilibrium that I describe in previous sections also describe the long-run equilibrium with one caveat. In order to stay in business in the long run, the monopoly must earn at least zero economic profit.

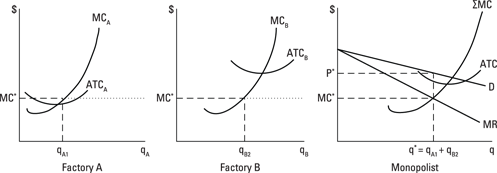

Producing with Multiple Facilities

Monopolists, as is the case for many other firms, often produce their product in more than one factory. In order to maximize profits, the monopolist must determine how to allocate production among these factories. In determining this allocation, the monopolist’s goal is to produce additional units at the lowest cost. Therefore, the monopolist produces additional units of the product in the factory that has the lowest marginal cost. As a result, the monopolist minimizes the total cost of producing the total amount of the product.

Getting each facility’s best

If the marginal cost of producing an additional unit of output in one factory is higher than the marginal cost of producing the additional unit of output in a second factory, you’re not minimizing total production costs. Your total costs are lower if you switch production from the factory with the higher marginal cost to the factory with the lower marginal cost.

Cost minimization requires that the marginal cost of the last unit produced in each factory is equal for all factories. Figure 10-5 illustrates cost minimization for a monopoly with two factories. The marginal cost curve in the far right diagram labeled ΣMC is the horizontal summation of the marginal cost curves for each factory. Figure 10-5 shows two factories, A and B. Thus, marginal cost equals MC* is associated with the output level qA1 in factory A and the output level qB2 in factory B. For the monopoly, it produces the output level q* at a marginal cost MC*. The output q* simply is the horizontal summation of the quantities each factory produces given MC*, or

![]()

Figure 10-5: Producing with multiple facilities.

Note in Figure 10-5 the monopolist wants to produce the output level q* and charge the price P* in order to maximize profits, because marginal revenue, MR, equals marginal cost, MC, in the far right diagram. In order to minimize the cost of producing q*, the monopolist must produce the output level in each factory that corresponds to MC*. Thus, q1 units are produced in factory A and q2 units are produced in factory B.

Calculating the best allocation with calculus

Calculus precisely determines the amount of output to produce in each factory — something that is difficult to determine graphically. Profit-maximizing production with multiple factories requires the satisfaction of the following equation

![]()

In other words, profit maximization requires that the monopolist’s overall marginal revenue, MR, equals the marginal cost of production at each of its factories — factory A, factory B, and out to factory I — however many factories there are.

The firm has two factories. Factory A’s total cost and marginal cost equations are

Factory B’s total cost and marginal cost equations are

As indicated, profit-maximization requires

![]()

By solving this set of equations simultaneously, the monopolist’s profit-maximizing quantity of output is determined, as well as the quantity of output that’s produced in each factory.

1. Set MCA = MCB and solve for qA as a function of qB.

![]()

![]()

![]()

2. Set MR = MCB.

![]()

3. Substitute qA + qB for q.

Because the total quantity of output the monopolist sells, q, is produced in some combination from factories A and B, the quantities produced in each factory added together must equal the quantity sold by the monopolist.

![]()

![]()

![]()

4. Substitute qA = –1,000 + 2qB from Step 1 for qA in Step 3’s equation.

![]()

5. Solve for qB.

![]()

6. Using the equation from Step 1, solve for qA.

![]()

7. Solve for q, the total quantity of output the monopolist sells.

![]()

8. Solve for P, the price the monopolist establishes.

P is determined by using the demand equation I give at the beginning of the example.

![]()

9. The monopolist’s total profit is determined by subtracting the total cost of producing the given output in each factory from total revenue.

So, the monopolist’s total profit is $96,500. Knowing how to minimize cost when producing in two or more facilities is even better than collecting $200 when you pass “Go” in the board game Monopoly.

The monopolist’s pricing decision is subject to the constraint imposed by consumer demand. If the monopolist charges too high of a price, nobody wants to buy its product. So, if the monopolist wants to sell more product, it must lower price as indicated by the market demand curve.

The monopolist’s pricing decision is subject to the constraint imposed by consumer demand. If the monopolist charges too high of a price, nobody wants to buy its product. So, if the monopolist wants to sell more product, it must lower price as indicated by the market demand curve.