Chapter 2

Supply and Demand: You Have What Consumers Want

In This Chapter

![]() Buying more with lower prices

Buying more with lower prices

![]() Producing more with higher prices

Producing more with higher prices

![]() Compromising on price at equilibrium

Compromising on price at equilibrium

![]() Moving toward equilibrium when shortages and surpluses occur

Moving toward equilibrium when shortages and surpluses occur

![]() Understanding why equilibrium changes

Understanding why equilibrium changes

The Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle said, “Teach a parrot the terms ‘supply and demand’ and you’ve got an economist.” Or there’s a story about a student standing next to an economist by a bank of elevators. Three elevators passed them on the way to the basement. The student said, “I wonder why everybody in the basement wants to go upstairs.” The economist responded, “You’re confusing supply with demand.” Or finally, there is an old joke, “Talk is cheap. Supply exceeds demand.”

The numerous jokes about supply and demand indicate its fundamental importance in economics. Indeed, if the parrot understood what the terms supply and demand meant, it wouldn’t be much of an exaggeration to say the parrot qualifies as an economist. The reason this isn’t an exaggeration is because understanding supply and demand enables you to understand how prices are determined and what causes prices to change. And in business decision-making, understanding how prices are determined means nearly everything.

How Much Is That Doggie in the Window? Setting Prices through Markets

A popular children’s song asks, how much is that doggie in the window? The song’s chorus goes:

How much is that doggie in the window?

The one with the waggley tail.

How much is that doggie in the window?

I do hope that doggie’s for sale.

The last line of the lyrics — “I do hope that doggie’s for sale” — is too vague. To an economist (see, economists can even ruin a children’s song), the question is not whether the doggie is for sale. Of course, it’s for sale. The question is how much does it cost.

If the price is very low, customers are more likely to buy the dog, but the store does not make much profit; it may even lose money. If the doggie is too expensive, nobody will buy it. So the question is what price will lead to someone buying the doggie while the store owner makes some profit.

This apparent conflict between customers wanting low prices and sellers wanting high prices is resolved in the market — or through supply and demand.

Demanding Lower Prices

The relationship between how much customers must pay for an item and how much customers buy is called demand. More precisely, demand shows the relationship between a good’s price and the quantity of the good customers purchase, holding everything else constant.

Wow! Holding everything else constant, even the dog’s waggley tail? Not quite, but holding things like income, customer preferences, and the price of other goods — say cats — constant. (Are cats a good?)

Distinguishing between quantity demanded and demand

To economists, quantity demanded is the amount of the good customers purchase at a given price. Quantity demanded is a specific number.

On the other hand, demand refers to the entire curve. Demand shows how much is purchased at every possible price.

Graphing demand

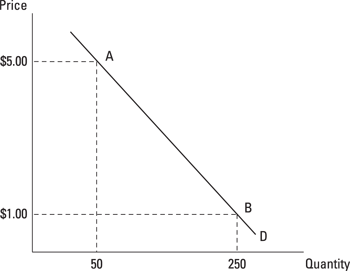

The graph of the demand curve enables you to focus on the relationship between price and quantity demanded. Figure 2-1 illustrates the demand curve for dog treats. (You want to keep that tail wagging.) The graph shows you that when prices are very high, customers want to buy fewer treats. More specifically, if the price of treats is $5.00, customers want to buy only 50 boxes of treats a week. On the other hand, if the price of treats decreases, say, to $1.00 a box, the quantity demanded of treats increases to 250 boxes a week.

Changing price

Price changes cause movements along the demand curve, or a change in quantity demanded. In Figure 2-1, when the price of dog treats decreased from $5.00 to $1.00, the quantity demanded increased from 50 to 250 boxes per week — a movement from point A to point B on the demand curve in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1: Changes in quantity demanded.

Shifting the demand curve

When one of the things being held constant — income, tastes, and the prices of other goods — changes, the entire demand curve shifts. For example, advertisements indicate that treats lead to happy dogs. People want happy dogs, so their preference for treats changes; dog treats become more desirable. So more dog treats are purchased, even though nothing happened to the price of dog treats.

Figure 2-2 illustrates the increase in demand as the curve shifts from D0 to D1. Because the desirability of dog treats increases, stores are selling a lot more dog treats. Stores were previously selling 250 boxes of treats per week at a price of $1.00. Now, with the price still $1.00, stores are selling more treats — 350 boxes a week. That point isn’t on the original demand shown in Figure 2-1. What happened is the demand curve shifts so that this new point is on the new demand curve, D1. Because the new demand curve is to the right of the original demand curve, economists say demand has increased.

Figure 2-2: Changes (shifts) in demand.

![]() Consumer tastes or preferences: A direct relationship exists between desirability (consumer tastes) and demand. Thus, an increase in desirability increases demand.

Consumer tastes or preferences: A direct relationship exists between desirability (consumer tastes) and demand. Thus, an increase in desirability increases demand.

![]() Income: Income’s impact on demand is a little more complicated. Economists note two types of goods — normal goods and inferior goods. For normal goods, a direct relationship exists between income and demand — an increase in income increases demand. This is the expected, or normal, relationship. For an inferior good, an increase in income decreases demand; therefore, an inverse relationship exists between income and demand for an inferior good.

Income: Income’s impact on demand is a little more complicated. Economists note two types of goods — normal goods and inferior goods. For normal goods, a direct relationship exists between income and demand — an increase in income increases demand. This is the expected, or normal, relationship. For an inferior good, an increase in income decreases demand; therefore, an inverse relationship exists between income and demand for an inferior good.

![]() Prices of other goods: Changes in the prices of other goods are also a little complicated. If the goods are consumer substitutes for one another, they are used interchangeably. Hot dogs and hamburgers at a picnic are an example of consumer substitutes. A direct relationship exists between one good’s price and the demand for the second, substitute, good. Thus, when the price of hot dogs increases, the entire demand curve for hamburgers shifts to the right (increases). Consumer complements are a second type of goods. Consumer complements are used together, such as coffee and cream. An inverse relationship exists between one good’s price and the demand for its consumer complement. As the price of coffee increases, the amount of coffee you drink decreases. This decrease in the quantity demanded of coffee is because you’re responding to a change in coffee’s price. And because you’re drinking less coffee, your demand for cream decreases. The higher price for coffee decreases your demand for cream — an inverse relationship. Even if the price of cream doesn’t change, you use less of it.

Prices of other goods: Changes in the prices of other goods are also a little complicated. If the goods are consumer substitutes for one another, they are used interchangeably. Hot dogs and hamburgers at a picnic are an example of consumer substitutes. A direct relationship exists between one good’s price and the demand for the second, substitute, good. Thus, when the price of hot dogs increases, the entire demand curve for hamburgers shifts to the right (increases). Consumer complements are a second type of goods. Consumer complements are used together, such as coffee and cream. An inverse relationship exists between one good’s price and the demand for its consumer complement. As the price of coffee increases, the amount of coffee you drink decreases. This decrease in the quantity demanded of coffee is because you’re responding to a change in coffee’s price. And because you’re drinking less coffee, your demand for cream decreases. The higher price for coffee decreases your demand for cream — an inverse relationship. Even if the price of cream doesn’t change, you use less of it.

Supplying Higher Prices

Holding everything else constant seems a little ambitious, even for economists, but there is a reason for that qualification. By holding everything else constant, supply enables you to focus on the relationship between price and the quantity provided. And that is the critical relationship.

Understanding quantity supplied and supply

Quantity supplied refers to the amount of the good businesses provide at a specific price. So, quantity supplied is an actual number. Economists use the term supply to refer to the entire curve. The supply curve is an equation or line on a graph showing the different quantities provided at every possible price.

Graphing supply

The supply curve’s graph shows the relationship between price and quantity supplied. Figure 2-3 illustrates the supply curve for dog treats. The graph indicates that when the price is very high, businesses provide a lot more treats. There’s money to be made in dog treats. But if the price of dog treats is very low, there’s not much money to be made, and businesses provide fewer dog treats. For example, if the price of treats is $5.00, businesses provide 650 boxes of treats a week. On the other hand, if the price of treats decreases to $1.00 a box, the quantity of treats provided decreases to 50 boxes a week.

Changing price

Figure 2-3 illustrates that price and quantity supplied are directly related. As price goes down, the quantity supplied decreases; as the price goes up, quantity supplied increases.

Figure 2-3: Changes in quantity supplied.

Shifting the supply curve

When economists focus on the relationship between price and quantity supplied, a lot of other things are held constant, such as production costs, technology, and the prices of goods producers consider related. When any one of these things changes, the entire supply curve shifts.

If an increase in supply occurs, the curve shifts to the right, as illustrated in Figure 2-4. In this case, an increase in supply shifted the curve from S0 to S1. As a result, more dog treats are provided at every possible price. For example, at a price of $5.00, 750 boxes of dog treats are provided each week instead of 650.

Figure 2-4: Changes (shifts) in supply.

The factors that shift the supply curve include

![]() Production costs: Input prices and resulting production costs are inversely related to supply. In other words, changes in input prices and production costs cause an opposite change in supply. If input prices and production costs increase, supply decreases; if input prices and production costs decrease, supply increases. For example, if wages or labor costs increase, the supply of the good decreases.

Production costs: Input prices and resulting production costs are inversely related to supply. In other words, changes in input prices and production costs cause an opposite change in supply. If input prices and production costs increase, supply decreases; if input prices and production costs decrease, supply increases. For example, if wages or labor costs increase, the supply of the good decreases.

![]() Technology: Technological improvements in production shift the supply curve. Specifically, improvements in technology increase supply — a rightward shift in the supply curve.

Technology: Technological improvements in production shift the supply curve. Specifically, improvements in technology increase supply — a rightward shift in the supply curve.

![]() Prices of other goods: Price changes for other goods are a little complicated. First, in order to affect supply, producers must think the goods are related. What consumers think is irrelevant. For example, ranchers think beef and leather are related; they both come from a steer. However, as a consumer, please don’t serve me leather for dinner.

Prices of other goods: Price changes for other goods are a little complicated. First, in order to affect supply, producers must think the goods are related. What consumers think is irrelevant. For example, ranchers think beef and leather are related; they both come from a steer. However, as a consumer, please don’t serve me leather for dinner.

Beef and leather are an example of joint products, products produced together. For joint products, a direct relationship exists between a good’s price and the supply of its joint product. If the price of beef increases, ranchers raise more cattle, and the supply of beef’s joint product (leather) increases.

Producer substitutes also exist; using the same resources, a business can produce one good or the other. Corn and soybeans are examples of producer substitutes. If the price of corn increases, farmers grow more corn, and less land is available to grow soybeans. Soybeans’ supply decreases. An inverse relationship exists between a good’s price (corn) and the supply of its producer substitute (soybeans).

Determining Equilibrium: Minding Your P’s and Q’s

Business executives face a dilemma: Customers want low prices, and executives want high prices. Markets resolve this dilemma by reaching a compromise price. The compromise price is the one that makes quantity demanded equal to quantity supplied. At that price, every customer who is willing and able to buy the good can do so. And every business executive who wants to sell the good at that price can sell it.

Figure 2-5 illustrates the equilibrium price for dog treats — the point where the demand and supply curve intersect corresponds to a price of $2.00. At this price, the quantity demanded (determined off of the demand curve) is 200 boxes of treats per week, and the quantity supplied (determined from the supply curve) is 200 boxes per week. Quantity demanded equals quantity supplied.

Figure 2-5: Determining the equilibrium price and quantity.

Determining the price mathematically

You can also determine the equilibrium price mathematically. In order to determine equilibrium mathematically, remember that quantity demanded must equal quantity supplied.

![]()

In the equation, QD represents the quantity demanded of dog treats, and P represents the price of a box of dog treats in dollars. Because a negative sign is in front of the term 50P, as price increases, quantity demanded decreases.

The supply of dog treats is represented by

![]()

The quantity supplied of dog treats is represented by QS in this equation, and P again represents the price for a box of dog treats in dollars. A positive sign in front of the 150P indicates a direct relationship exist between price and quantity supplied.

To determine the equilibrium price, do the following.

1. Set quantity demanded equal to quantity supplied:

![]()

2. Add 50P to both sides of the equation.

You get

![]()

3. Add 100 to both sides of the equation.

You get

![]()

4. Divide both sides of the equation by 200.

You get P equals $2.00 per box. This is the equilibrium price.

Producing too much: Stuff lying everywhere

Gas prices keep rising, and customers no longer want to buy large cars with low gas mileage. The car dealer’s lot is full of large cars, and more are on the way. The dealership has an excess supply of cars.

Figure 2-6 illustrates the car surplus. At $35,000 per car, the quantity demanded is only 10 cars per month, while the quantity supplied is 30 cars. Thus, a surplus, or excess supply, of 20 cars exists. The managers don’t want these cars sitting on the lot, so they lower the price. At the same time, they cancel future orders, reducing quantity supplied. And because of the lower price, customers buy more cars. In the end, the price per car falls to the equilibrium price of $30,000 in Figure 2-6, the quantity supplied by the dealer decreases from 30 to 15, and the quantity demanded by customers increases from 10 to 15. At the price of $30,000, the market is in equilibrium because quantity demanded equals quantity supplied.

Figure 2-6: Surplus or excess supply.

Producing not enough: The cupboard is bare

It’s Christmas, and you know what the “hot” gift is. You know because you have been to six stores and can’t find it anywhere. Or it’s the biggest basketball game of the year, and you just have to go but the tickets are sold out. In these situations, you’re encountering a shortage.

Suppose that the hot gift next Christmas is baseball cards of famous economists. (Yes, such things really exist, but bubble gum isn’t included.) As illustrated in Figure 2-7, at a price of $5.00 per set, the quantity supplied is 1,500 sets, while the quantity demanded is 5,000 sets. A shortage or excess demand of 3,500 sets exists. As the producer realizes the cards are selling out, the producer raises price to $10.00 per set, and some customers decide the cards are too expensive, so quantity demanded decreases to 3,000 sets. At the same time, the producer also increases production (there is a lot of money to be made in famous economist cards), so the quantity supplied increases to 3,000. The market has reached equilibrium, as illustrated in Figure 2-7, because the quantity demanded of 3,000 equals the quantity supplied. And this occurs at the equilibrium price of $10.00.

Figure 2-7: Shortage or excess demand.

Changing equilibrium: Shift happens

Markets tend toward equilibrium, the price and quantity that correspond to the point where supply and demand intersect. But equilibrium itself can change.

Figure 2-8 illustrates what happens when demand increases. Originally, the market was in equilibrium at price P0 and quantity Q0. If demand increases, the demand curve shifts to the right from D0 to D1. The quantity demanded associated with the price P0 is now QD. Because this is greater than the quantity producers are providing (still Q0 as determined off the supply curve), a shortage exists. The market moves from the original equilibrium price P0 to the new equilibrium price P1 and from the original equilibrium quantity Q0 to the new equilibrium quantity, Q1.

Figure 2-8: Changing equilibrium due to an increase in demand.

The impact of an increase in supply is illustrated in Figure 2-9. Originally, the equilibrium price and quantity are P0 and Q0, respectively. An increase in supply shifts the supply curve to the right from S0 to S1. The supply increase immediately creates a surplus because at P0, the new quantity supplied QS is greater than the quantity demanded, which is still at Q0. Because there is a surplus, the good’s price falls from P0 to the new equilibrium price P1, and the quantity demanded and quantity supplied move to the new equilibrium quantity Q1, which is greater than the original equilibrium quantity Q0.

There are instances where both demand and supply shift at the same time, and this makes determining the changes in equilibrium price and quantity more difficult.

Figure 2-9: Changing equilibrium due to an increase in supply.

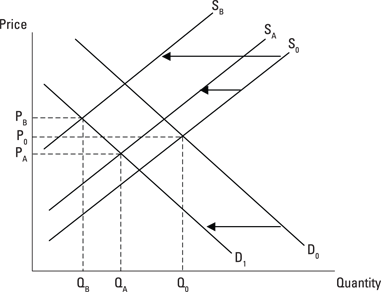

Figure 2-10 illustrates a simultaneous decrease in both demand and supply — the demand curve shifts left from D0 to D1, and the supply curve shifts left from S0 to S1. The original equilibrium price and quantity are P0 and Q0, corresponding to the intersection of the original demand and supply curves. Given the shifts to D1 and S1, the equilibrium quantity decreases from Q0 to Q1 while the equilibrium price has not changed — P0 = P1. But note that in Figure 2-10, the demand and supply curves shift by the same amount.

In Figure 2-11, two decreases in supply are illustrated along with the decrease in demand. The first decrease in supply is a relatively small one, from S0 to SA. The new equilibrium quantity decreases from Q0 to QA, and the equilibrium price also decreases from P0 to PA. The second decrease in supply is a relatively large one, from S0 to SB. In this case, the new equilibrium quantity still decreases, now from Q0 to QB. But note what happens to equilibrium price: It increases from P0 to PB. Given the decrease in demand, a small decrease in supply results in a lower equilibrium price, while a large decrease in supply results in a higher equilibrium price.

Figures 2-10 and 2-11 illustrate that when both demand and supply simultaneously decrease, equilibrium quantity always decreases, but equilibrium price can increase, decrease, or remain the same. So, only one equilibrium characteristic — equilibrium quantity — can be definitely determined.

Figure 2-10: A simultaneous decrease in both demand and supply.

Figure 2-11: An indeterminate change in equilibrium price.

Quantity demanded and demand sound like the same thing. Indeed, as you read the newspaper, you’re likely to see demand all the time and never see quantity demanded. (That’s because very few reporters take economics classes.) But to economists, there is a big difference between the terms quantity demanded and demand.

Quantity demanded and demand sound like the same thing. Indeed, as you read the newspaper, you’re likely to see demand all the time and never see quantity demanded. (That’s because very few reporters take economics classes.) But to economists, there is a big difference between the terms quantity demanded and demand.

The demand for dog treats is represented by the following equation

The demand for dog treats is represented by the following equation