Chapter 13

Monopolistic Competition: Competitors, Competitors Everywhere

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding the impact of competition

Understanding the impact of competition

![]() Setting price with many rivals

Setting price with many rivals

![]() Disappearing profit in the long run

Disappearing profit in the long run

![]() Advertising ideals

Advertising ideals

Mothers often say, “Just worry about yourself.” Well, that’s a great attitude to have in monopolistic competition — just worry about yourself. Indeed, in monopolistic competition, that’s all you can do. Monopolistically competitive markets have a large number of firms producing similar, but not identical, products. Thus, the products are differentiated, although their use is almost identical. Because there are so many firms, you can’t pay attention to all of them, so you need to focus on your own actions. This situation is very different from oligopoly (see Chapter 11) where you have to pay attention to rivals.

One of monopolistic competition’s most important characteristics is that firms produce slightly different products. Because of these product differences, each monopolistically competitive firm sets price. But any profit that results from the price you set can’t last. The intense competition that exists in monopolistically competitive markets ultimately eliminates economic profit in the long run.

In this chapter, I explain how a large number of rivals affect your decision-making. I present how the profit-maximizing quantity and price are determined in the short run, and why the short-run decision ultimately causes profit to disappear in the long run. Finally, I present how you determine the ideal level of advertising expenditures.

Competing with Rivals All Around You in Monopolistic Competition

Although competitive behavior in oligopolies leads to mutual interdependence, monopolistically competitive markets are closer in similarity to perfectly competitive markets (see Chapter 9). Monopolistically competitive firms and perfectly competitive firms do, however, have one crucial difference. Although monopolistically competitive firms produce a standardized type of commodity, some differentiation exists among the goods produced by different firms. As a result, monopolistically competitive firms produce goods that are used in similar ways (standardized type of commodity), while some small difference, such as flavor, color, and/or branding, exists. On the other hand, perfectly competitive firms produce goods with no differentiation.

Pizza is an example of a monopolistically competitive market. You know what a pizza is, and it is essentially the same type of product at any restaurant — it’s a standardized type of product. But not all pizzas are identical; hence, you probably have a favorite. The differences that lead to you having a favorite pizza represent differentiation, and as a result, firms in monopolistically competitive markets are able to set the price they receive for their good. You’re willing to pay a little more for your favorite pizza.

Characterizing Monopolistic Competition

The three major characteristics of monopolistically competitive markets are:

![]() Large number of firms: Because an individual firm is one out of a large number of firms, it provides a fairly small percentage of the good available in the market. Therefore, the individual firm has limited influence on the commodity’s price. In addition, because of the large number of firms, monopolistically competitive firms don’t regard themselves as being mutually interdependent and don’t take into account how rivals respond to their actions. Finally, the large number of firms prevents collusive behavior in monopolistically competition.

Large number of firms: Because an individual firm is one out of a large number of firms, it provides a fairly small percentage of the good available in the market. Therefore, the individual firm has limited influence on the commodity’s price. In addition, because of the large number of firms, monopolistically competitive firms don’t regard themselves as being mutually interdependent and don’t take into account how rivals respond to their actions. Finally, the large number of firms prevents collusive behavior in monopolistically competition.

![]() Standardized type of commodity with interfirm differentiation: Monopolistically competitive firms produce a standardized type of commodity with slight differentiation among firms. Several factors account for this product differentiation. For example, differences in product quality or the type of service performed can lead to differentiation. The firm’s location is another source of the differentiation. Finally, differentiation may result from interfirm differences in promotion and packaging.

Standardized type of commodity with interfirm differentiation: Monopolistically competitive firms produce a standardized type of commodity with slight differentiation among firms. Several factors account for this product differentiation. For example, differences in product quality or the type of service performed can lead to differentiation. The firm’s location is another source of the differentiation. Finally, differentiation may result from interfirm differences in promotion and packaging.

![]() Easy entry and exit: A monopolistically competitive market has no barriers to entry. New firms can easily establish themselves in the market, and similarly, existing firms can easily exit the market. Typically, easy entry and exit occurs because monopolistically competitive firms have relatively small fixed costs, so existing firms don’t significantly benefit from lower per-unit production costs as compared to new firms.

Easy entry and exit: A monopolistically competitive market has no barriers to entry. New firms can easily establish themselves in the market, and similarly, existing firms can easily exit the market. Typically, easy entry and exit occurs because monopolistically competitive firms have relatively small fixed costs, so existing firms don’t significantly benefit from lower per-unit production costs as compared to new firms.

Setting Price with Many Rivals

Interfirm differentiation allows the monopolistically competitive firm to set price. Therefore, the firm determines both the profit-maximizing quantity and the good’s price. However, the degree of influence the firm has on price is limited because a large number of rival firms are producing similar products.

Recognizing the importance of product differentiation

The degree of influence a monopolistically competitive firm has on the good’s price is dependent on the price elasticity of demand for the firm’s good. The more elastic the demand, the less influence the firm has on price, because quantity demanded is very responsive to any price change. Two factors that influence the monopolistically competitive firm’s price elasticity of demand are the number of firms, and the degree of product differentiation among firms.

A large number of firms results in consumers having a greater number of alternatives from which to choose. Therefore, consumers are more responsive to price changes. If your firm increases price, your customers are more likely to switch to one of your rivals. As a consequence, with a larger number of rival firms, the demand for your firm’s good is more elastic and you have less influence over price.

A small degree of product differentiation also results in consumers being less concerned about which firm they purchase the good from. If firms produce nearly identical products (that is, the products have very little differentiation), consumers are very responsive to any price changes that occur. Because the products are so similar, consumers simply look for the lowest price. This minimizes your firm’s ability to charge a higher price. If you charge a higher price, most of your customers simply switch to a product produced by a competitor that has a lower price. Your quantity demanded goes down a lot. As a consequence, the demand for your firm’s product is more elastic — consumers are very responsive to any price change you make.

Making use of advertising and product differentiation

Monopolistically competitive firms engage in non-price competition, such as advertising and innovation.

With both advertising and innovation, you’re trying to increase the degree of differentiation that exists between the good you produce and the goods produced by your rivals. In the case of advertising, you may stress that your pizza is made from the freshest ingredients.

Innovation is also a source of differentiation. You may introduce a new type of pizza — anchovy and spinach, anyone? — to attract new customers.

Maximizing short-run profit

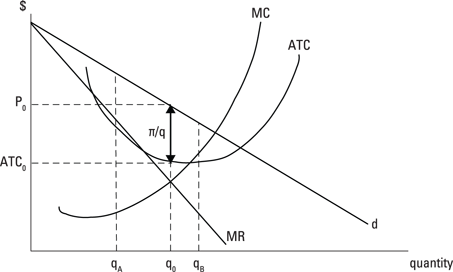

Because a monopolistically competitive firm produces a differentiated good, short-run profit maximization requires the firm to determine both the profit-maximizing quantity and the good’s price. Figure 13-1 illustrates short-run profit maximization for a monopolistically competitive firm.

Differentiation leads to a downward-sloping demand curve for the monopolistically competitive firm. This curve is labeled d in Figure 13-1. Because the demand curve is downward sloping, the monopolistically competitive firm must lower price in order to sell more of the good. This lower price is charged for all units of the good sold.

Marginal revenue represents the change in total revenue that occurs when one additional unit of output is produced and sold. Because the firm must charge a lower price for every unit sold in order to sell one additional unit of the good, marginal revenue is lower than the price of the last unit sold. The marginal-revenue curve, thus, lies below the demand curve, as illustrated by the curve labeled MR in Figure 13-1.

Figure 13-1: Short-run profit maximization in monopolistic competition.

Marginal cost is the change in total cost that occurs when one additional unit of output is produced. Because of diminishing returns, marginal cost, MC, is upward-sloping, as illustrated in Figure 13-1. In addition, marginal cost passes through the minimum point of the average-total-cost curve, ATC. I describe these relationships in more detail in Chapter 8.

The firm’s total profit increases if an additional unit of output adds more to revenue than it adds to cost. As long as the marginal revenue of an additional unit exceeds marginal cost, as is the case at qA, producing that unit increases the firm’s total profit, and the firm should continue to produce more. On the other hand, if a unit of output adds more to cost than it adds to revenue, as with qB, or if marginal cost is greater than marginal revenue, producing that unit decreases the firm’s total profit. The firm needs to reduce production. The monopolistically competitive firm maximizes profit by producing the quantity of output associated with marginal revenue equals marginal cost. The profit-maximizing quantity of output is represented by q0 in Figure 13-1.

After determining the profit-maximizing quantity of output, the firm establishes the good’s price by going from that quantity, q0 in Figure 13-1, to the demand curve and across to the vertical axis. The profit-maximizing price is P0 in Figure 13-1.

The monopolistically competitive firm determines profit per unit by subtracting average total cost from price. In Figure 13-1, profit per unit is represented by π/q and equals price minus average total cost. Total profit, π, equals profit per unit multiplied by the profit-maximizing quantity, or

![]()

Relying on calculus in monopolistic competition

Profit is always maximized at the quantity where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. To determine marginal revenue, you take the derivative of total revenue with respect to quantity. To determine marginal cost, you take the derivative of total cost with respect to quantity.

![]()

where P is the good’s price in dollars and q is the quantity produced by the monopolistically competitive firm.

Also assume your total cost equation is

![]()

where TC is total cost in dollars and q is the quantity of the good produced.

Given these equations, the profit-maximizing quantity of output, price, and profit are determined through the following steps:

1. Determine total revenue.

Total revenue equals price multiplied by quantity.

![]()

2. Determine marginal revenue.

Marginal revenue is the derivative of total revenue taken with respect to quantity.

![]()

3. Determine marginal cost by taking the derivative of total cost with respect to quantity.

![]()

4. Set marginal revenue equal to marginal cost and solve for q.

5. Substitute 15,000 for q in the demand equation to determine price.

![]()

Thus, the profit maximizing quantity is 15,000 units and the price is $32.50 per unit.

The following steps enable you to determine the firm’s economic profit per unit and total profit.

6. Determine the average total cost equation.

Average total cost equals total cost divided by the quantity of output q.

![]()

7. Substitute q equals 15,000 in order to determine average total cost at the profit-maximizing quantity of output.

![]()

Thus, average total cost is $28.70 at the profit-maximizing quantity of 15,000 units.

8. Calculate profit per unit.

![]()

Profit per unit equals $3.80.

9. Determine total profit.

Total profit equals profit per unit multiplied by the profit-maximizing quantity of output.

![]()

Total profit equals $57,000.

Adjusting to the Long-Run Tendency of Profit Elimination

Easy entry and exit indicate that firms have little or no difficulty in moving into and out of a monopolistically competitive market. If firms perceive an opportunity to earn economic profit in this market, they enter the market. The entry of new firms results in demand decreasing for other firms in the market as some customers switch to the new firm. Entry continues until the typical firm’s demand decreases to the point where the firm earns zero economic profit. At that point, new firms no longer have incentive to enter.

Similarly, if initial economic losses (negative economic profit) exist, firms leave the market. This loss of firms results in an increase in demand for firms remaining in the market until zero economic profit is reached. Demand increases for remaining firms as customers for the firms that left switch to surviving firms.

Figure 13-2 illustrates the movement to the long-run equilibrium from an initial situation with positive economic profit. Initially, the firm’s demand and marginal revenue curves correspond to d* and MR*. Given these curves and the illustrated cost curves, the profit-maximizing quantity and price are q* and p*. The firm is earning positive profit because price is greater than average total cost at q*.

Figure 13-2: Long-run equilibrium in monopolistic competition.

Because the firm is earning positive economic profit, new firms enter the market. The entry of new firms causes the original firm’s demand to decrease to dLR as some of the firm’s customers switch to the new firms. The decrease in demand causes marginal revenue to decrease to MRLR. The resulting new profit-maximizing quantity is qLR and price is pLR. At this point, price equals average total cost, as represented by the demand curve being just tangent to the average total cost curve. Because price equals average total cost, firms earn zero economic profit, and new firms no longer have incentive to enter the market.

Determining the Ideal Amount of Advertising

One factor contributing to product differentiation in monopolistically competitive markets is advertising. Determining the appropriate or profit-maximizing level of advertising is crucial to the firm’s success.

Advertising’s affect on consumer taste and preferences enables it to influence consumer demand for a product. For the monopolistically competitive firm, an increase in advertising increases demand for its product, while a decrease in advertising decreases the firm’s demand. However, in addition to shifting demand, you must recognize that changes in advertising expenditures affect your cost.

Mathematically, the additional profit that’s made through the production and sale of one additional unit of output is price minus marginal cost, P – MC. The change in gross profit that occurs with an additional dollar spent on advertising equals the change in the quantity sold that occurs, Δq, multiplied by P – MC. This amount is gross profit, because it doesn’t include the cost of advertising. The monopolistically competitive firm’s net profit increases as long as each additional dollar spent on advertising generates more than an additional dollar’s worth of gross profit. In other words, net profit increases as long as

![]()

In order to maximize the net profits associated with advertising, the firm should continue increasing advertising expenditures until

![]()

At this point, an additional dollar’s worth of advertising adds one dollar to gross profit, resulting in no gain in the firm’s net profit.

If you take the previous equation and divide both sides by (P – MC), you get

![]()

Now, multiplying both sides of the equation by P yields

![]()

At the point of profit maximization, marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Substituting MR for MC in the equation leads to

![]()

Chapter 4 shows that the right side of this equation equals the negative price elasticity of demand, η, for the firm’s product. The left side of the equation represents the marginal revenue of an additional dollar’s worth of advertising. Therefore, the optimal level of advertising expenditures corresponds to

![]()

Wow, there’s the price elasticity of demand again. Maybe mothers should stop saying, “Just worry about yourself,” and instead say, “Just remember your price elasticity of demand.”

1. Determine the marginal revenue of an additional dollar’s worth of advertising.

Divide the additional revenue by the additional amount spent on advertising to determine the marginal revenue of an additional dollar’s worth of advertising.

![]()

2. Determine the negative price elasticity of demand.

![]()

3. Make your decision.

Because the marginal revenue associated with an additional dollar’s worth of advertising is less than –η (1.60 < 2.0) you should not advertise. In order to justify advertising, the marginal revenue of an additional dollar’s worth of advertising has to be greater than 2.0.

Product differentiation gives firms some degree of monopoly power so they can establish the good’s price. On the other hand, perfect standardization, such as exists in prefect competition, results in the firm having no influence on price. Perfectly competitive firms are price takers.

Product differentiation gives firms some degree of monopoly power so they can establish the good’s price. On the other hand, perfect standardization, such as exists in prefect competition, results in the firm having no influence on price. Perfectly competitive firms are price takers.