Chapter 14

Increasing Revenue with Advanced Pricing Strategies

In This Chapter

![]() Using elasticity to determine price

Using elasticity to determine price

![]() Basing price on cost

Basing price on cost

![]() Selling the same good at different prices

Selling the same good at different prices

![]() Bundling goods for a bundle of profit

Bundling goods for a bundle of profit

![]() Pricing for competitive wars

Pricing for competitive wars

You’ve probably seen the game show The Price Is Right. In the show, contestants are shown a product and asked to guess its price. The contestant who guesses closest to the actual retail price without going over is declared the winner.

The question of the right price is crucial in business decision-making. The price marked on a product isn’t necessarily the right price. As a consumer, I tend to think that most prices are wrong — they’re way too high. For a business losing money, the price probably seems way too low. Before deciding whether or not a price is right, you need to know what your goal is.

Throughout this book, I emphasize various methods to determine price. In this chapter, I introduce more advance pricing techniques. I start by looking at how to determine price by using the price elasticity of demand, and then move to two of the simplest strategies — cost-plus pricing and breakeven analysis. Next comes a more advanced strategy — price discrimination. Price discrimination enables you to charge different prices for the same good. I wonder how that would work on the television show The Price Is Right. Another advanced pricing strategy is to bundle goods. Rather than sell goods individually to the customer, you allow the customer to buy them together as a bundle — think Happy Meal. The chapter concludes with short-run pricing strategies that temporarily reduce profit in order to earn even greater profit in the future.

Simplifying Price Determination by Using the Price Elasticity of Demand

Long-term success and profitability depend upon producing a good to the point where the additional revenue of an extra unit of output equals the additional cost of producing that unit; in other words, producing where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Previous chapters derive marginal revenue from the firm’s demand. However, an easier method of deriving marginal revenue is to use the price elasticity of demand.

Chapter 4 notes the following relationship between marginal revenue and the price elasticity of demand:

![]()

where MR is marginal revenue, P is the good’s price, and η is the price elasticity of demand.

Maximizing profit requires marginal revenue equals marginal cost, so

![]()

![]()

Thus, the profit-maximizing price equals

![]()

1. Substitute $6.00 for MC and –4.0 for η.

![]()

2. Calculate the value in the parentheses.

![]()

3. Multiply values to yield a price of $8.00.

Pricing Based upon Cost: Cost-Plus Pricing and Breakeven Analysis

Two pricing policies you commonly encounter in business are cost-plus pricing and breakeven pricing. These policies are very simple pricing strategies based upon production costs. Simple doesn’t mean better or worse. The advantage of simple in these cases is that calculating price is easy. The disadvantage of these simple strategies is that they ignore demand. Thus, it’s important to understand under what circumstances these simple methods of price determination help you reach your goal of maximum profit.

Cost-plus pricing

Cost-plus pricing means that you determine price by starting with the good’s cost and then adding a fixed percentage or amount to that cost. One of the primary reasons cost-plus pricing is so popular is its simplicity. Often information on marginal revenue and marginal cost is difficult to obtain with precision, making it impossible to exactly determine the point of profit maximization. By using cost-plus pricing, you can simply include a desired rate of return in the mark-up. Another advantage of cost-plus pricing is its desirability from the standpoint of public relations. This pricing technique provides an obvious rationale for price increases when cost increases occur.

Cost-plus pricing typically involves two steps. First, the firm determines the per unit cost or average total cost of producing the good. Because average total cost varies as the quantity of output produced changes, the firm’s determination of per unit cost requires the specification of an output level. After the firm establishes the per unit cost, the firm adds a mark-up to the per unit cost. The mark-up is typically in the form of a percentage, and it represents costs that can’t be easily allocated to a specific product produced by the firm plus a return on the firm’s investment.

The following equation illustrates how to determine price with cost-plus pricing:

![]()

where P is the good’s price, ATC is the average total cost or cost per unit, and the mark-up is the percentage added to average total cost.

One criticism of cost-plus pricing is that it focuses on average rather than marginal costs. Because profit maximization requires marginal cost equals marginal revenue, cost-plus pricing may not result in profit maximization. Another criticism of cost-plus pricing is that it ignores demand conditions. By ignoring demand, the firm can establish a cost-plus price that’s above the market’s equilibrium price, resulting in a surplus. As a consequence, the firm doesn’t sell all the units it produces.

It’s logical to wonder whether cost-plus pricing ever maximizes profit. In order for profit-maximization to occur, cost-plus pricing must result in the firm producing the output level where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In the short-run, the difference between marginal cost and average total cost may be sizeable. However, studies have shown that long-run average total cost is typically constant for many firms. Constant long-run average total cost implies constant marginal cost; therefore, marginal cost equals average total cost in this situation. The use of average total cost in the place of marginal cost for pricing results in minimal differences, or

![]()

Still, because this simple approach ignores demand, it’s unlikely to result in maximum profit. However, when you use marginal cost in the previous equation, it looks very similar to the profit-maximizing equation in the previous section of this chapter.

![]()

Thus, if one plus your mark-up equals the second part of the earlier equation, or

![]()

cost-plus pricing maximizes your profit.

Manipulating the earlier equation allows you to determine the mark-up

![]()

1. Substitute –4 for the price elasticity of demand in the mark-up equation.

![]()

2. Calculate the value of the denominator.

![]()

3. Divide the numerator by the denominator.

The resulting value is 0.33, or the markup should be 33%.

Breakeven analysis

A firm using breakeven analysis determines the smallest output level that leads to zero economic profit. Recall that zero economic profit doesn’t mean that the firm’s owners receive nothing — it means that the firm’s owners are receiving a normal rate of return. In other words, the firm’s owners are receiving exactly as much as they would in their next best alternative.

In breakeven pricing, your total revenue equals total cost — hence, zero profit. Because the focus is on the point where you earn zero profit, it’s unlikely that breakeven analysis maximizes your profit.

However, breakeven analysis is a useful managerial tool. Managers use breakeven analysis to determine how a price change affects profit. If you lower price, how many more units do you have to sell in order to achieve zero profit — or to break even? If your firm has a large fixed cost, breakeven analysis enables you to determine the quantity of output you must sell in order to avoid losses. In either of these situations, as a manager, you can then determine whether or not sales of that amount are feasible.

1. Set total revenue equal to total cost.

Remember that total revenue equals price multiplied by the quantity sold, and total cost equals total fixed cost plus total variable cost.

![]()

2. Substitute AVC×q for TVC.

Recall that total variable cost equals average variable cost multiplied by the number of units produced q.

![]()

3. Subtract AVC×q from both sides of the equation in Step 2 and simplify.

![]()

4. Divide both sides of the equation by (P – AVC).

This step enables you to solve for the breakeven quantity, q.

![]()

5. Substitute the values for TFC, P, and AVC and solve for q.

![]()

Your breakeven quantity is 100,000 units.

Discriminating among Customers

Price discrimination refers to a situation where the same good is sold to different groups of consumers for different prices. For example, the couple sitting next to you at the movie paid a lower price to get in because they’re senior citizens. Or, perhaps you get a student discount at a local restaurant that non-students don’t get.

Price discrimination exists in a variety of situations. Therefore, economists define different degrees of price discrimination to reflect the various situations associated with this pricing policy. However, no significance is attached to whether or not price discrimination is of the first degree or third degree — one isn’t more important than the other. (See the upcoming section “Identifying Who Wants to Pay More: Types of Price Discrimination” for details on the different degrees of price discrimination.)

Recognizing the conditions necessary for price discrimination

Price discrimination requires the following conditions

![]() You can segment the market into customers who have different price elasticities of demand.

You can segment the market into customers who have different price elasticities of demand.

![]() The firm possesses some degree of monopoly power and can set price.

The firm possesses some degree of monopoly power and can set price.

![]() Finally, customers can’t resell the good. If customers are able to resell the good, those who pay a lower price can buy the good and sell it for a higher price, but not as high as the firm charges, to customers willing to pay the high price. This process is called arbitrage, and it limits the firm’s ability to benefit from price discrimination.

Finally, customers can’t resell the good. If customers are able to resell the good, those who pay a lower price can buy the good and sell it for a higher price, but not as high as the firm charges, to customers willing to pay the high price. This process is called arbitrage, and it limits the firm’s ability to benefit from price discrimination.

Assessing price discrimination’s impact

Firms that engage in price discrimination generally

![]() Produce a greater quantity of output. Because the firm is able to charge different prices to different groups of consumers, it can attract more buyers who are willing to pay a low price without sacrificing revenue from buyers willing to pay a higher price. By selling to both groups at different prices the firm increases the quantity of the good it sells.

Produce a greater quantity of output. Because the firm is able to charge different prices to different groups of consumers, it can attract more buyers who are willing to pay a low price without sacrificing revenue from buyers willing to pay a higher price. By selling to both groups at different prices the firm increases the quantity of the good it sells.

![]() Increase their profit. By charging different prices, the firm is able to capture more consumer surplus — the difference between the price a consumer is willing to pay and the price the consumer actually pays. This additional consumer surplus adds to the firm’s producer surplus.

Increase their profit. By charging different prices, the firm is able to capture more consumer surplus — the difference between the price a consumer is willing to pay and the price the consumer actually pays. This additional consumer surplus adds to the firm’s producer surplus.

Identifying Who Wants to Pay More: Types of Price Discrimination

As a business owner, you want customers to pay higher prices. Obviously those same customers want to pay lower prices. But as a demand curve illustrates, the prices some customers are willing and able to pay are much higher than the prices others are willing and able to pay. You can increase your profit if you’re able to separate customers who are willing to pay higher prices from those willing to pay lower prices.

Wishing for first-degree price discrimination

First-degree price discrimination, sometimes referred to as perfect price discrimination, exists when a firm charges a different price for each unit of the good sold — every customer pays a different price for the good. This degree is the ultimate extreme in price discrimination — hence, its designation as “perfect.”

When first-degree price discrimination exists, the firm’s marginal revenue curve corresponds to its demand curve. Because a different price — the maximum price each customer is willing and able to pay — is set for each unit of the good, each unit adds its price to total revenue. So, marginal revenue, the change in total revenue, equals the price determined from the demand curve.

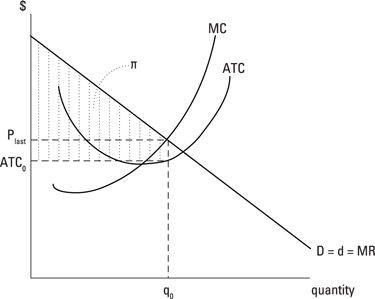

Figure 14-1 illustrates a monopoly that’s using first-degree price discrimination. In the graph, marginal cost, MC, and average total cost, ATC, have the usual shapes with marginal cost passing through the minimum point on the average-total-cost curve. The firm faces a downward-sloping market demand curve that’s the same as the firm’s demand curve, D = d, given that it’s a monopoly. Because the firm charges every consumer the maximum price he or she is willing to pay, marginal revenue corresponds to the firm’s demand curve, d = MR.

Profit maximization occurs at the output level corresponding to marginal revenue equals marginal cost, q0 in Figure 14-1. Each unit of output has a unique price, so Plast is the price only for the last unit sold. Every other unit has a higher price. The resulting profit for the firm equals the revenue it receives for each unit minus the average total cost per unit, ATC0. Because the price for each unit is the maximum price as determined from the demand curve, the shaded area labeled π in Figure 14-1 represents the firm’s total profit.

Figure 14-1: First-degree price discrimination.

Using second-degree price discrimination

Charging different prices for different ranges or blocks of output results in second-degree price discrimination or declining block pricing. Typically, consumers pay one price for the first, small block of output, and lower prices for additional ranges or blocks of output. Electric companies frequently use this type of price discrimination. For example, an electric company charges 9 cents per kilowatt hour for the first 300 kilowatt hours of electricity used in a month, 5 cents per kilowatt hour for the block 301 to 1,000 kilowatt hours, and 4 cents for each kilowatt hour over 1,000. A consumer using 1,200 kilowatt hours pays $70.00 = $0.09 × 300 + $0.05 × 700 + $0.04 × 200.

A firm engaging in second-degree price discrimination faces a marginal revenue curve that appears as a series of steps. The marginal revenue curve is a horizontal line corresponding to the price for that block of output. Figure 14-2 illustrates second-degree price discrimination.

Figure 14-2: Second-degree price discrimination.

The marginal-cost, MC, and average-total-cost, ATC, curves in Figure 14-2 have the typical shape. The firm in Figure 14-2 represents a monopoly so the downward-sloping market demand corresponds to the firm’s demand curve, D = d.

To derive the marginal-revenue curve, note for the block of output from 0 to qA, you charge PA for each unit of output. Thus, each unit adds PA to your total revenue and PA is your marginal revenue. For the block of output from qA to qB, you charge the lower PB and your marginal revenue “steps down” to correspond to PB. For the block of output from qB to q0, you again lower price, this time to P0, and marginal revenue takes another step down to P0. To sell more units of output beyond q0, you have to further lower price, so marginal revenue continues to take steps down. Marginal revenue, MR, in Figure 14-2 reflects this series of steps.

The profit-maximizing firm always produces the output level corresponding to marginal revenue equals marginal cost. This is the output level q0 in Figure 14-2. The firm doesn’t charge a single price. Instead, the firm charges the price PA for the block of output from 0 to qA, PB for the block of output from qA to qB, and P0 for the remaining output.

The amount of profit the firm receives for each unit is the difference between price and average total cost, so the shaded area labeled with the symbol π in Figure 14-2 represents the firm’s total profit. Note that the profit area in second-degree price discrimination is smaller than the profit area illustrated in Figure 14-1 for first-degree price discrimination.

Applying third-degree price discrimination

Third-degree price discrimination exists when you partition the market into two or more different groups of consumers based upon different price elasticities of demand. The differences in elasticity enable you to charge customers in each group purchasing the good different prices. Groups possess different price elasticities of demand for any number of reasons. Differences in income, tastes, or availability of substitutes can account for variation in elasticities. Examples of third-degree price discrimination include different prices for senior citizens, variation in airline ticket prices depending upon when the ticket is purchased, and student discounts.

After you determine that you can separate potential consumers into two or more groups with different price elasticities of demand, you must determine the quantity of output to sell to each group and the good’s price for each group. Assuming your goal is profit maximization (and why wouldn’t it be?), you allocate output in order to satisfy two criteria. First, you sell the quantity of output that results in the marginal revenue of the last unit sold to each group equal for all groups. Second, the marginal revenue of the last unit sold to any group must equal the marginal cost of the last unit your firm produces. If marginal revenue isn’t equal for all groups, you can increase profit by reallocating units of the good to the group that has the higher marginal revenue. If marginal revenue is greater than marginal cost, you’re able to increase profit by producing more units of output.

Figure 14-3 illustrates third-degree price discrimination. The curves labeled dA and MRA represent the demand and marginal revenue for the group A consumers. Because this demand curve is relatively steep, it’s less elastic. Similarly, the curves labeled dB and MRB represent the demand and marginal revenue for group B consumers. Group B’s flatter demand curve indicates a more elastic demand.

The marginal cost of the last unit you produce is constant and labeled MC*. The profit-maximizing quantity for each group corresponds to the output where the group’s marginal revenue equals marginal cost. To determine price, you go from the profit-maximizing output level up to the group’s demand curve and across to the vertical axis. For group A, the profit-maximizing quantity is qA0 and the price is PA. For group B, the profit-maximizing quantity is qB0 and the price is PB.

Figure 14-3: Third-degree price discrimination.

Determining third-degree price discrimination with calculus (if you’re interested)

In order to determine the profit-maximizing price and quantity for each group of customers by using third-degree price discrimination, you must satisfy the condition

![]()

where MRA is group A’s marginal revenue for the last unit it buys, MRB is group B’s marginal revenue for the last unit it buys, and MC is marginal cost for the last unit you produce.

![]()

where PA is the price in dollars charged to group A customers, and qA is the quantity sold to group A customers. Group B’s demand is

![]()

where PB is the price in dollars charged to group B customers, and qB is the quantity sold to group B customers.

Your firm’s total cost and marginal cost equations are

where TC is your total cost in dollars, MC is marginal cost in dollars, and q is the total quantity of the good your firm produces.

Using this information and the following steps, you can determine the price to charge each group of consumers, how much to sell each group of consumers, and how much to produce:

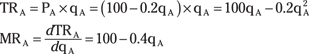

1. Determine the marginal revenue for group A customers.

First, multiply the demand equation by qA to determine total revenue, and then take the derivative of total revenue with respect to qA to determine marginal revenue.

2. Determine the marginal revenue for group B customers.

First, determine total revenue by multiplying PB by qB, and then take the derivative of total revenue with respect to qB to determine marginal revenue.

3. Set MRA = MC.

![]()

4. Substitute qA + qB for q.

The total quantity of output you produce and sell, q, is sold to customers in either group A or group B.

![]()

5. Solve the equation in Step 4 for qB.

6. Set MRA equal to MRB.

![]()

7. Substitute qB = 950 – 5qA in the equation in Step 6.

![]()

8. Solve for qA.

![]()

9. Substitute qA = 150 in group A’s demand equation to determine the price, PA, to charge customers in group A.

![]()

10. Substitute qA = 150 in the equation from Step 5 to determine qB.

![]()

11. Substitute qB = 200 in group B’s demand equation to determine the price, PB, to charge customers in group B.

![]()

12. Determine the total quantity of output that your firm produces.

![]()

Your firm produces 350 units of the good. It sells 150 units to customers in group A at a price of $70 per unit and 200 units to customers in group B at a price of $60 per unit.

Pricing coupons

Coupons are a very effective way to price discriminate. Customers who are very responsive to price changes — that is, customers with a very elastic demand — are likely to take time to find coupons that effectively lower the good’s price. On the other hand, customers less responsive to price changes because of their less elastic demand aren’t as likely to take the time to find coupons.

When you use coupons, you start by establishing a single price for the good. The price is then lower for customers possessing a coupon. So, customers not using a coupon pay the price P, while customers using the coupon pay the price P – C, where C represents the coupon’s value.

In essence, coupons are another way to implement third-degree price discrimination. The rule for maximizing profit with third-degree price discrimination is

![]()

The first section in this chapter notes that marginal revenue is a function of the price elasticity of demand, or

![]()

Assume that customers in group A have the less elastic demand; therefore, they pay the good’s full price P. Customers in group B have the more elastic demand and use a coupon. These customers essentially pay the price P – C for the good. Combining the last two equations with this information yields

![]()

where P is the good’s price, C is the coupon’s value, ηA is the price elasticity of demand for group A customers who have a less elastic demand, ηB is the price elasticity of demand for group B customers who have a more elastic demand, and MC is marginal cost.

Use the following steps to determine the price to charge for a meal and the coupon’s value:

1. The following equation maximizes profit.

In the equation, P is the price of a restaurant meal in dollars, C is the coupon’s value in dollars, ηV is the price elasticity of demand for vacation travelers, ηL is the price elasticity of demand for local residents, and MC is marginal cost in dollars.

![]()

2. Determine the price for a restaurant meal.

Use the vacation traveler portion of the equation in Step 1 and marginal cost.

3. Determine the coupon’s value.

Use the price determined in Step 2 and the local resident portion of the equation in Step 1.

Your restaurant should establish a price of $18.00 for a meal. It should provide $9.00 coupons to local residents. One method of providing coupons to local residents that would generally exclude vacation travelers is to use advertising mailers delivered to local addresses or publish coupons in local newspapers.

Making a Bundle through Bundling

Bundling refers to a situation where you package two or more goods together and sell them as a single unit. Firms use bundling to increase profit — make a bundle. A fast food restaurant may bundle a sandwich, French fries, and soft drink, selling all three bundled together for a single price.

You’re most likely to increase profit by bundling goods that have large differences in the prices customers are willing to pay. Economists use the term reservation price to indicate the price where the consumer is indifferent between purchasing the good or continuing to search for a lower price. In essence, the reservation price is the maximum price the consumer is willing to pay.

Effective bundling requires you to package goods that are negatively correlated across consumers. Therefore, for some consumers, good A has a high reservation price, and good B has a low reservation price. For other consumers, good A has a low reservation price, and good B has a high reservation price. This reverse relationship or negative correlation across consumers enables you to bundle goods A and B and have both sets of consumers purchase the bundle consisting of goods A and B. The result is all customers buy both goods instead of having only the consumers with high reservation prices buying the good.

Using pure bundling

Pure bundling exists when consumers can only purchase the goods together. It isn’t possible to purchase the goods separately. This pricing strategy is found in many restaurants where the entrée comes automatically with a side dish — the entrée and side dish can’t be purchased separately. Satellite and cable television also use pure bundling — you can’t pick and choose the channels you want; you must choose among the packages offered by the service.

Figure 14-4 illustrates pure bundling for two computer software programs — a word-processing program, Software W, and a spreadsheet program, Software X. In order to simplify the analysis, 1,200 customers are uniformly distributed over the range of possible reservation prices for both software programs. The reservation prices for Software W appear on the vertical axis and range from $0 to $40.00. The reservation prices for Software X appear on the horizontal axis and range from $0 to $30.00.

Figure 14-4: Pure bundling.

Assume that you initially price each software program separately. You charge $20.00 for Software W and $15.00 for Software X. These prices divide the upper panel in Figure 14-4 into four quadrants of equal size. Going back to the assumption that you have 1,200 customers, each quadrant represents one-quarter of the customers or 300 customers. Given this situation, 300 customers purchase only Software W at $20.00 because their reservation price is $20.00 or higher. These customers are in block A of the figure.

Another 300 customers purchase only Software X because their reservation price is higher than Software X’s $15.00 price. These customers are in block C of the figure. A third group of customers is in block B. These customers buy both Software W and Software X because their reservation price for Software W is higher than $20.00 and their reservation price for Software X is higher than $15.00. Finally, the customers in block D don’t buy anything, because their reservation price for Software W is less than $20.00 and their reservation price for Software X is less than $15.00.

Your total revenue in this case equals $21,000. To determine your total revenue, you take the following steps:

1. Calculate the revenue for customers who purchase only Software W.

Multiply 300 customers by the $20.00 price.

![]()

2. Calculate the revenue for customers who purchase only Software X.

Multiply 300 customers by the $15.00 price.

![]()

3. Calculate the revenue for customers who purchase both Software W and Software X.

Multiply 300 customers by $35.00, the combined prices of Software W, $20.00, and Software X, $15.00.

![]()

4. Add the revenue you receive from all three groups of customers.

![]()

By pricing each software program separately, you earn $21,000 in revenue.

Instead of selling each software program separately, you can sell them as a pure bundle — customers must buy software programs W and X together. In this situation, you charge a single price for both programs — for example, you set a price of $24.00 for a package containing both Software W and Software X. The lower panel in Figure 14-4 describes this situation.

Customers consider whether or not to purchase the pure bundle by adding together their reservation prices for Software W and Software X. So, if the customer’s reservation price for Software W is $22.00 and the customer’s reservation price for Software X is $16.00, the customer purchases the pure bundle because the combined reservation price of $38.00 is higher than the actual price of $24.00. However, note that given these reservation prices, this customer purchases the two software programs even if they’re priced separately at $20.00 and $15.00.

On the other hand, another customer has a reservation price of $18.00 for Software W and $10.00 for Software X. If the software programs are priced separately at $20.00 and $15.00, this customer purchases neither program. The customer’s reservation price is less than the actual price for each program. However, if the software programs are sold as a bundle for $24.00, the customer purchases the bundle because the customer’s combined reservation price of $28.00 — $18.00 plus $10.00 — is higher than the actual price of $24.00. Thus, you’re able to sell the pure bundle to customers who purchase nothing if the programs are priced separately. This enables you to increase your revenue. In the lower panel of Figure 14-4, the diagonal line separates the customers who don’t purchase the pure bundle, the lower left corner, from customers who do purchase the bundle, the upper right shaded area.

Allowing mixed bundling

Mixed bundling allows customers to purchase the goods either together as a bundle or separately. One of the crucial differences between mixed bundling and pure bundling is that some customers purchase only a single item. These customers have a reservation price greater than the actual price for one item. However, they don’t buy the bundle because the difference between the bundle price and the price of the first item is less than their reservation price for the second item.

For example, say you’re willing to pay $30.00 for Software W and only $2.00 for Software X. In addition, the price of Software W separately is $20.00, the price of Software X separately is $15.00, and the price of the bundle is $24.00. Obviously, you’re willing to buy Software W separately — its $20.00 price is less than your reservation price of $30.00. Similarly, you’re not willing to buy Software X separately because its $15.00 price is greater than your reservation price of $2.00.

In a surprising result, you’re not willing to buy the bundle. To move from buying Software W for $20.00 to buying the bundle requires you to pay $24.00. This is $4.00 more than you have to pay to purchase Software W alone. Because your reservation price for Software X is only $2.00, it’s not worth spending the extra $4.00 to buy the bundle. The point labeled U in Figure 14-5 represents this situation.

Figure 14-5: Mixed bundling.

In order for you to purchase the bundle, the difference between the separate price for the first item and the bundle price must be less than your reservation price for the second item. Now assume that your reservation price for Software W remains $30.00, but your reservation price for Software X is $7.00. In this situation you’ll buy the bundle because you’re willing to pay $30.00 for Software W. That’s higher than Software W’s actual price. You can then add Software X for another $4.00 because the price of the bundle is $24.00. So, instead of purchasing Software W alone for $20.00, you can purchase the bundle including both Software W and Software X for $24.00. Because Software X is worth $7.00 to you, adding Software X to the bundle is worth it to you. You get something you’re willing to pay $7.00 for and it costs you only an extra $4.00.

In Figure 14-5, the vertical shaded area represents customers who buy only Software W. Note for this shaded area, customers’ reservation prices for Software W are higher than Software W’s $20.00 price. However, their reservation prices for Software X are less than $4.00. Because adding Software X to the bundle costs $4.00, they’re not willing to buy the bundle.

The horizontal shaded area represents customers who buy only Software X. In this horizontal shaded area, customers’ reservation prices for Software X are higher than its $15.00 price. If these customers add Software W to the bundle, it increases the price by $9.00 to $24.00. For this group of customers, their reservation prices for Software W are less than $9.00; so, they’re not willing to add Software W to their purchase of Software X.

Customers in the diagonal shaded area buy the bundle of Software W and Software X. For these customers, the reservation price of adding the second software package to the bundle is greater than the price difference. Finally, the area that isn’t shaded represents customers who don’t buy any software package.

So You Want War: Pricing for Business Battles

I know a bicycle rider who once passed another bicycle rider on a hill. When passed, the second bicycle rider said, “I didn’t know it was a race.” To which the first rider responded, “It’s always a race.”

In a very real sense, businesses are always at war fighting battles with one another. Businesses compete for resources and customers. The wages one business pays for labor affect what other businesses have to pay, and the price one business charges its customers affects the price other businesses charge.

This section describes three weapons that help you fight these battles.

Penetration pricing: Here I come

Firms use penetration pricing to quickly establish a large market share. In order to attract customers, the firm establishes a very low price. This is a useful strategy for a new firm entering a market.

Effective penetration pricing requires a very elastic demand for the good. Because customers are very responsive to price changes, establishing a low price leads to a large increase in quantity demanded. Later, if you’re successful in establishing customer loyalty, you can raise the price.

In addition to attracting new customers, an effective penetration price leads to lower per unit costs if economies of scale are present. By quickly attracting customers, you can establish a large market share leading to economies of scale that become a barrier to entry for other firms thinking about entering the market.

Penetration pricing is also used to sell complementary products. For example, a low penetration price on a game console can lead to more sales of compatible games that have high mark-ups.

You need to take into account several factors before using penetration pricing. First, consider whether your firm is able to produce enough output to satisfy customers. If you run out of product to sell, customers are likely to be dissatisfied with you. Second, price can’t be associated with quality. If customers associate a low price with poor quality, they won’t buy the product. Finally, if rivals meet the lower price you charge, the advantages of penetration pricing are negated.

Limit pricing: Keep out

Firms use limit pricing to prevent other firms from entering the market. Limit pricing occurs when the firm establishes a price below the profit-maximizing level. The lower price leads to a higher quantity demanded, leaving very little residual demand for a new firm to satisfy.

Figure 14-6 illustrates limit pricing. Initially, the market is a monopoly, so the market-demand curve, D, corresponds to the firm’s demand curve, d. As I note in Chapter 10, the marginal-revenue curve associated with a linear demand curve starts at the same point on the vertical axis and is twice as steep as the demand curve. The monopoly’s marginal-revenue curve in Figure 14-6 is labeled MR.

Figure 14-6: Limit pricing.

Given typical average total cost and marginal cost curves, the profit-maximizing monopolist produces the quantity q0, based on marginal revenue equals marginal cost, and charges the price P0. The monopolist’s economic profit per unit is the difference between price and average total cost as represented by the double-headed arrow labeled π/q.

The positive economic profit the monopolist earns attracts new firms. If these firms enter the market, the existing firm’s profit decreases or perhaps even disappears. So, to discourage entry, the monopolist charges a lower price, PL. At this price, the monopolist must produce qL to satisfy consumer demand.

Firms considering whether or not to enter the market now see an entirely different situation. The potential demand for an entering firm equals the market demand minus the quantity, qL, provided by the current firm. The entrant’s residual demand curve is represented by dE and the associated marginal revenue curve is MRE. The entering firm would then produce where its marginal revenue equals marginal cost. (For the moment, assume the entering firm has exactly the same costs as the current monopoly.) The entering firm’s profit-maximizing quantity and price are qE and PE. But at this output level, price equals average total cost, so the entering firm earns zero profit. Thus, the new firm has no incentive to enter the market, and the original firm has succeeded in keeping rivals out.

Predatory pricing: Get out

Predatory pricing is used to drive existing rival firms out of a market. With predatory pricing, a firm establishes a price that’s below its marginal cost. After the rival leaves the market, the remaining firm, or predator, raises price in order to increase its profit. The predator in essence is trading a temporary short-run loss for higher future profit.

Predatory pricing depends upon the correct assessment of the relative health of the predator and prey. The predator is assuming that it’s healthier than the prey and can withstand the temporary losses better than the prey. If the predator is wrong in this assessment, predatory pricing can backfire and leave the predator vulnerable.

Successful predators establish a reputation as tough, perhaps even ruthless, rivals. This reputation is likely to deter future entry so that you can realize additional benefits.

Sometimes, the right price is as simple as the price associated with a mutually beneficial exchange. Both the customer and the firm are willing to buy and sell at that price. But as a business manager, you want to find the price that maximizes profit — that is, your right price.

You should charge customers who have a less elastic demand a higher price, because a less elastic demand means the customer is less responsive to price changes. Customers whose demand is more elastic are more responsive to price changes. These customers should be charged a lower price in order to get them to buy a lot more.

You should charge customers who have a less elastic demand a higher price, because a less elastic demand means the customer is less responsive to price changes. Customers whose demand is more elastic are more responsive to price changes. These customers should be charged a lower price in order to get them to buy a lot more.