Chapter 16

Using Capital Budgeting to Prepare for the Future

In This Chapter

![]() Preparing for capital investments

Preparing for capital investments

![]() Determining capital’s cost

Determining capital’s cost

![]() Choosing the best capital investments

Choosing the best capital investments

Purchasing machinery and equipment and building factories require spending today in order to receive future revenue. Thus, capital budgeting is one of the most important and yet uncertain decision-making areas because it’s critically influenced by time.

Capital budgeting decisions require a substantial amount of forecasting — I hope you have your crystal ball or Magic 8 ball handy. Biased or poorly developed forecasts adversely affect the quality of investment decisions. Therefore, techniques for evaluating capital investment projects have limited value in the absence of unbiased, well-developed forecasts.

In this chapter, I show you the critical components for evaluating alternative investment projects and selecting from them. That process includes understanding critical aspects of estimating future cash flows and procedures for determining the cost of capital. Understanding these critical components provides the foundation for comparing and evaluating alternative investment projects.

Investing in Capital

Economists define capital as the machinery, equipment, and factories you use in the production process. Investment refers to the purchasing of capital.

Investment requires long-term decisions. You spend/invest money and incur a cost today in order to realize future revenue. Although they’re always long-term, investment decisions address different purposes and have different affects on the firm. Investment purposes include the following:

![]() Replacement investment decisions are expenditures to replace existing machinery and equipment. A restaurant deciding to replace kitchen equipment and a firm replacing assembly line machinery are examples of replacement investment decisions.

Replacement investment decisions are expenditures to replace existing machinery and equipment. A restaurant deciding to replace kitchen equipment and a firm replacing assembly line machinery are examples of replacement investment decisions.

![]() Modernization investment decisions reduce production costs. A modernization decision emphasizes more efficient operation — it may involve the renovation of a factory or the installation of automated machinery.

Modernization investment decisions reduce production costs. A modernization decision emphasizes more efficient operation — it may involve the renovation of a factory or the installation of automated machinery.

![]() Expansion investment decisions increase the firm’s productive capacity or introduce new products or markets. A firm’s decisions to build an additional factory or expand sales to a new region are examples of expansion decisions.

Expansion investment decisions increase the firm’s productive capacity or introduce new products or markets. A firm’s decisions to build an additional factory or expand sales to a new region are examples of expansion decisions.

![]() Operating investment decisions involve changes in inventories. Economists regard inventory as an investment because inventory represents goods produced but not immediately sold. A car dealer may increase the number of cars it keeps to interest new customers.

Operating investment decisions involve changes in inventories. Economists regard inventory as an investment because inventory represents goods produced but not immediately sold. A car dealer may increase the number of cars it keeps to interest new customers.

![]() Seed investment decisions represent investment expenditures whose returns aren’t immediately realized. Typical seed investment decisions include expenditures into research and development, training, market research, and advertising.

Seed investment decisions represent investment expenditures whose returns aren’t immediately realized. Typical seed investment decisions include expenditures into research and development, training, market research, and advertising.

![]() Pollution-control or safety investment decisions include investments necessary for compliance with regulations established by government agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). In addition, investments related to worker safety may be required by labor agreements or insurance policies.

Pollution-control or safety investment decisions include investments necessary for compliance with regulations established by government agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). In addition, investments related to worker safety may be required by labor agreements or insurance policies.

Each type of investment decision represents an immediate cash outlay for some future revenue or benefit.

Selecting among Alternative Investments

You face a variety of investment opportunities at any given point of time; therefore, it’s important to develop criteria that enable you to choose among these projects. Determining which projects to undertake during a given period determines your firm’s current capital expenditures. In addition, the projects selected influence your firm’s future operations and profit.

In determining whether or not to invest in a project, you still maximize profits. To accomplish this goal, you undertake all investment projects that have marginal revenue exceeding marginal cost (MR>MC). In capital budgeting, the investment’s rate of return represents marginal revenue, while the firm’s cost of capital represents marginal cost.

Figure 16-1 illustrates the capital budgeting process. The investment return curve, IR, represents the anticipated return on various investment projects. The curve is disjointed, reflecting the different sizes and returns for various projects. For example, project A requires a $10 million investment and yields an expected 18-percent rate of return. Project B requires a $30 million investment — increasing the total capital investment to $40 million — and yields an expected 15-percent return. The downward tendency of the curve indicates that you undertake investment projects with highest expected return first.

The investment return curve in Figure 16-1 is disjointed, reflecting the fixed investment required for each project. Thus, project A requires a $10 million investment — a partial investment can’t be made.

Figure 16-1: Investment selection process.

The cost of capital curve, CC, indicates the marginal cost of obtaining each additional investment dollar. In Figure 16-1, this curve is horizontal until $30 million, representing a constant cost of capital at 8 percent. After $30 million, the curve slopes upward, indicating rising cost associated with the firm’s increasing debt load.

In Figure 16-1, you spend $60 million on investment projects A, B, and C. The first $30 million invested costs 8 percent, and the marginal cost of the last dollar invested is 9 percent. You won’t invest in projects D and E because their expected return (IR) is less than the cost of the money invested (CC).

The actual capital budgeting process is more complicated than Figure 16-1 implies. First, proposals for potential investment projects have to be generated. Then you must estimate future cash flows and the cost of capital for those projects. With this information, you can evaluate the alternative investment proposals and determine which, if any, to pursue. Finally, after their implementation, projects are subject to ongoing review.

Estimating Cash Flows in an Uncertain Environment

Estimates of future cash flows — both cash receipts and expenditures — are a crucial element in any investment decision. Four important elements enter into the determination of future cash flows.

![]() Cash flows must be determined on an incremental basis. Only include cash flows that are directly affected by whether or not the project is accepted.

Cash flows must be determined on an incremental basis. Only include cash flows that are directly affected by whether or not the project is accepted.

![]() All affected cash flows must be included in the calculation. An investment project’s impact on other activities of the firm must be included. For example, if a restaurant is evaluating a new menu item, it must consider the impact the item’s introduction has on the sales of current menu items.

All affected cash flows must be included in the calculation. An investment project’s impact on other activities of the firm must be included. For example, if a restaurant is evaluating a new menu item, it must consider the impact the item’s introduction has on the sales of current menu items.

![]() Cash flows are determined on an after-tax basis. Estimated cash flows are dependent upon the firm’s marginal tax rate.

Cash flows are determined on an after-tax basis. Estimated cash flows are dependent upon the firm’s marginal tax rate.

![]() Because depreciation isn’t associated with a cash flow, it shouldn’t be directly included. However, any impact depreciation has on taxes is incorporated in cash-flow estimates.

Because depreciation isn’t associated with a cash flow, it shouldn’t be directly included. However, any impact depreciation has on taxes is incorporated in cash-flow estimates.

As these elements indicate, the determination of cash flows is heavily dependent upon your accounting data.

Budgeting for Capital

Firms raise investment funds through both internal and external sources. Methods for raising funds internally include using retained earnings or funds the owner contributes, while external financing includes borrowing money or issuing more stock. Regardless of how funds are raised, the firm incurs costs.

Determining the Cost of Capital

The cost of capital associated with external funds is easily recognized as the interest you have to pay on the borrowed funds. Internal funds represent using equity — either the firm’s or the firm’s owner’s financial resources — to finance the project. However, internal funds also cost you — even if you contribute those funds.

Using internal funds: I’ll pay for it myself

Because the cost of using internally generated funds or equity is the lost opportunity for you to invest these funds in the next best alternative, you must use a method that estimates the return the next best alternative generates. Typically, one of three methods — risk-premium, dividend-valuation, or capital-asset pricing — is used to determine the cost of internal or equity capital.

Risk-premium method

The risk premium method assumes that you incur some additional risk in the investment. This method’s cost estimation uses a risk-free rate of return, rf, plus an additional risk premium, rp, or

![]()

where ke is the cost of equity capital. It’s common to use the U.S. Treasury Bill rate as the risk-free rate of return (rf). The risk premium (rp) that’s added to the risk-free rate of return has two components. First, it includes the difference between the interest rate on company bonds as compared to the U.S. Treasury Bill rate. Second, it includes an additional premium reflecting the added risk of owning the specific company’s stock instead of its bonds. The risk premium has historically averaged four percent; however, this amount varies substantially among companies and over different length time periods.

Dividend-valuation method

The dividend valuation method uses shareholder attitudes to determine the cost of equity capital. Shareholder wealth is a function of dividends and changing stock prices. Therefore, a shareholder’s rate of return is a function of the ratio of the dividend, D, divided by the stock price per share, P, plus the expected or historic earnings growth, g. Using this shareholder return as the cost of equity capital results in

![]()

1. Determine the ratio of D/P.

This ratio determines the rate of return your invested funds earn through dividends.

![]()

2. Add the historic growth rate to the D/P ratio.

This determines the cost of equity capital by including the anticipated growth in the stock’s price.

![]()

Capital-asset-pricing method

The third method for estimating the cost of equity capital is the capital-asset-pricing method. This method incorporates a risk premium for variability in a company’s return. The risk premium is higher for stocks whose returns are more variable, and lower for stocks with stable returns. The formula used to determine the cost of equity capital using the capital-asset-pricing method is

![]()

where rf is the risk-free return, km is an average stock’s return, and β measures the variability in the specific firm’s common stock return relative to the variability in the average stock’s return. If β equals 1, the firm has average variability or risk. β values greater than 1 indicate higher than average variability or risk while values less than 1 indicate below average risk. The term β(km – rf) gives the risk premium for holding the firm’s common stock.

1. Determine the risk premium.

The risk premium is determined by subtracting the risk-free rate of return from the average stock’s return and multiplying by β.

![]()

2. Add the risk premium to the risk-free rate of return.

This addition determines the cost of equity capital by including the risk premium.

![]()

Relying on external funds: Help!

The cost of using external funds, or the cost of debt capital, is the interest rate you must pay lenders. However, because interest expenses are tax deductible, the after-tax cost of debt, kd, is the interest rate, r, multiplied by 1 minus the firm’s marginal tax rate, t, or

![]()

![]()

Calculating the composite cost of capital

Firms commonly raise funds for capital investment from both internal and external sources. The composite cost of capital, kc, is a weighted average of the cost of equity capital and the cost of debt capital. Therefore,

![]()

where we and wd are the weights or proportions of equity and debt capital you use to finance the project.

1. Determine the cost of equity capital.

In this example, I’m using the capital-asset-pricing method.

![]()

2. Determine the cost of debt by using the marginal tax rate.

![]()

3. Determine the composite cost of capital.

Remember to weight each component by the percentage of funds raised through that method — equity or debt.

![]()

Thus, the composite cost of capital is 7.33 percent.

Avoiding pitfalls in capital budgeting

George Burns is credited with saying, “Look to the future, because that is where you’ll spend the rest of your life.” This quote is the essence of capital budgeting. But trying to guess the future makes it easy to make some common mistakes.

One common mistake is to overestimate your cost of capital. Business managers are often conservative, so they want to screen out all but the most promising projects. The consequence of this very conservative strategy is that profitable investment projects aren’t undertaken.

Another common error is for firms to assume profit levels won’t change even if capital investment isn’t undertaken. Because rival firms are investing, the lack of investment ultimately leads to profits eroding. Estimated cash flows should reflect this incremental difference. If they don’t, new project profitability is underestimated.

Firms must also be careful not to exclude qualitative factors. Investment may enable you to decrease production time, enabling you to fill customer orders in a more timely fashion. Although this impact is difficult to quantify, there’s no doubt that it positively affects your firm’s sales and profitability.

Finally, firms typically are too cautious with ambitious projects. Smaller investments are frequently undertaken with minimal management approval, while larger projects may require several levels of management approval. As a consequence, managers have an incentive to propose smaller rather than larger projects.

Evaluating Investment Proposals

After determining cash flows and the cost of capital, managers can begin to evaluate various investment alternatives. The most commonly employed technique for evaluating investment alternatives is the net present value technique. Variations of this technique include the profitability index and the internal rate of return.

Determining today’s net present value

The net present value (NPV) technique is based on the concept that you prefer receiving cash today rather than in the future. One obvious reason for this preference is the fact that cash received today can earn interest through the purchase of government securities or other types of bonds. Therefore, any future cash you receive needs to be discounted by an appropriate interest rate.

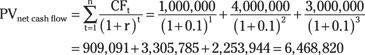

If all the capital investment project’s expenditures occur during the current year, the project’s net present value (NPV) equals

![]()

where CFt represents the net after-tax cash flow in year t, r is the cost of capital, and I is the capital investment project’s cash outlay assumed to occur in the current year, or year 0. I summarize the determination of r in the previous section.

1. Determine the present value for the first year’s cash flow.

Divide the first year’s net cash flow by (1 + r)1.

![]()

2. Determine the present values for the second, third, and fourth years’ cash flow.

Note how the exponent changes in the denominator of the calculation.

3. Add the four years’ present values.

![]()

4. Determine the capital investment project’s net present value.

Subtract the initial investment required from the sum of the four years’ present values.

![]()

5. Don’t make the capital investment.

Because the project’s net present value is negative, you shouldn’t invest in the project.

Indexing profitability

The profitability index is a variation of the net present value technique. The profitability index (PI) is calculated as follows

![]()

where PI represents the profitability index, CFt represents the net after-tax cash flow in year t, r is the cost of capital, and I is the capital investment project’s cash outlay assumed to occur in the current year, or year 0.

An important advantage of the profitability index is realized when circumstances prevent you from undertaking all profitable investments. In these situations, you use the profitability index to rank projects, undertaking projects with the highest profitability index first.

1. Determine the present value for the firm’s future net cash flow.

2. Divide the project’s present value of future cash flows by the project’s cost.

3. Because the profitability index is greater than 1, you should undertake the project.

An index value greater than 1 indicates the present value of future cash flows exceeds the project’s initial cost.

Calculating the internal rate of return

Calculating the internal rate of return is another alternative application of the net present value technique. The internal rate of return is the interest rate that equates the project’s present value of future net cash flows with the project’s initial investment outlay. Mathematically,

![]()

The Normal is solved for r*, which represents the internal rate of return.

The firm’s optimal investment level corresponds to the intersection of the investment return curve and the cost of capital curve. In

The firm’s optimal investment level corresponds to the intersection of the investment return curve and the cost of capital curve. In  The opportunity cost of funds you invest in the firm is the interest you could have earned if you had invested those funds elsewhere. This cost is very real, and your investment project has to generate enough cash to offset this lost opportunity.

The opportunity cost of funds you invest in the firm is the interest you could have earned if you had invested those funds elsewhere. This cost is very real, and your investment project has to generate enough cash to offset this lost opportunity. Your firm’s stock currently sells at $24.00 a share and the current annual dividend is $0.96. Your firm’s historic growth rate is 5 percent. Given this information, use the following steps to calculate the cost of equity capital by using the dividend-valuation method:

Your firm’s stock currently sells at $24.00 a share and the current annual dividend is $0.96. Your firm’s historic growth rate is 5 percent. Given this information, use the following steps to calculate the cost of equity capital by using the dividend-valuation method: