Chapter 9

Limited Decision-Making in Perfect Competition

In This Chapter

![]() Discovering that perfect competition has no competition

Discovering that perfect competition has no competition

![]() Maximizing profit in perfect competition

Maximizing profit in perfect competition

![]() Calculating profit

Calculating profit

![]() Knowing when to quit

Knowing when to quit

![]() Eliminating profit in the long run

Eliminating profit in the long run

Baseball player Yogi Berra once said, “If the world was perfect, it wouldn’t be.” That quote actually fits the economist’s idea of perfect competition — please forgive me — perfectly.

When economists use the term perfect competition, they don’t refer to competition at all. Indeed, perfect competition is the least competitive business environment there is. In perfect competition, you can’t set your product’s price and you have no incentive to advertise or innovate. You don’t compete with other firms. (However, you still have an incentive to minimize your production costs.) See, Yogi Berra is a lot smarter than you think — maybe he would have been an even better economist than he was a baseball player.

What perfect competition really refers to is a special outcome. As the owner of a firm in perfect competition, you choose to produce the quantity of output that maximizes profit; however, you can’t determine price. Price is determined by market forces that are outside your control. Ultimately, perfectly competitive markets reach a long-run equilibrium where the product’s price equals minimum cost per unit. For you as a business owner, this means zero profit — not what you hope for. For consumers, however, this represents the lowest price that continues to result in the product being available.

This chapter provides an overview of perfect competition, and as Yogi Berra would say, “It ain’t over ‘til it’s over.”

Identifying the Characteristics of Perfect Competition

Perfect competition has four primary characteristics:

![]() A large number of firms: Your firm is one of a large number of firms, so it produces a negligible amount of the total quantity of the commodity provided in the market. Therefore, if you decide to produce and sell a greater quantity of the commodity in the market, your decision (and extra production) doesn’t substantially alter market conditions.

A large number of firms: Your firm is one of a large number of firms, so it produces a negligible amount of the total quantity of the commodity provided in the market. Therefore, if you decide to produce and sell a greater quantity of the commodity in the market, your decision (and extra production) doesn’t substantially alter market conditions.

![]() Standardized commodity: All firms produce a standardized or homogeneous commodity, which means the commodity produced by your firm is no different from the commodity produced by any other firm. An example of a standardized commodity is wheat. If you’re a farmer, the wheat you grow is no different from the wheat grown by any other farmer, so consumers don’t care who grows the wheat that’s in the bread they purchase.

Standardized commodity: All firms produce a standardized or homogeneous commodity, which means the commodity produced by your firm is no different from the commodity produced by any other firm. An example of a standardized commodity is wheat. If you’re a farmer, the wheat you grow is no different from the wheat grown by any other farmer, so consumers don’t care who grows the wheat that’s in the bread they purchase.

![]() Easy entry and exit: There are no barriers to entry in perfect competition. Therefore, new firms can easily establish themselves in the market, and similarly, existing firms can easily exit the market. Typically, this easy entry and exit occurs because perfectly competitive firms have relatively small fixed costs.

Easy entry and exit: There are no barriers to entry in perfect competition. Therefore, new firms can easily establish themselves in the market, and similarly, existing firms can easily exit the market. Typically, this easy entry and exit occurs because perfectly competitive firms have relatively small fixed costs.

![]() Perfect information: The good’s price and quality are known to all buyers and sellers.

Perfect information: The good’s price and quality are known to all buyers and sellers.

Given these characteristics, a perfectly competitive firm is a price taker. The firm can’t set price; rather, the firm “takes” the price established by the market’s supply and demand.

Making an Offer the Firm Can’t Refuse: Market Price

As a result of perfect competition’s characteristics, each firm is a price taker. When a firm is a price taker, price is established through supply and demand in the market. The perfectly competitive firm must then sell its product at the market-established price. The firm’s owner can’t set price! Under these conditions, you can determine only the quantity of output to produce in order to maximize profits, and what inputs to use to minimize costs.

If an individual firm attempts to charge a price that’s higher than the market price, consumers will buy the product from one of the large number of rival firms who sell the product at the lower market price. Because the firm charging a higher price provides a negligible amount of the total market output, all consumer demand is easily satisfied by the other firms. Therefore, the firm charging the higher price is unable to sell any of its product.

On the other hand, the firm won’t want to charge a price lower than the market price. If the firm can sell everything it produces at the market price, charging a lower price simply means lower revenue and profit.

Competing with Advertising

Advertising’s purpose is to enable the firm to sell more product at a higher price. In a perfectly competitive market, advertising is a waste of money. The perfectly competitive firm doesn’t gain anything through advertising; indeed, the firm loses money if it advertises.

Because the perfectly competitive firm is a price taker, advertising doesn’t enable it to charge a higher price, and because the firm can already sell any quantity of output it produces, it has no need to advertise to sell more.

Sprinting to Maximum Short-Run Profit

Given the perfectly competitive firm is a price taker, the firm simply determines the quantity of output to produce in order to maximize profits. The firm can’t determine the product’s price; hence, the idea of limited decision-making. In addition, the firm can’t change its fixed cost in the short run. Therefore, the firm must choose the level of variable inputs that results in the profit-maximizing output level.

Determining price is out of your control

Given the perfectly competitive firm is a price taker, price is determined through the interaction of supply and demand in the market. Markets always move toward equilibrium, so the market-determined price ultimately is the price that makes quantity demanded equal to quantity supplied.

![]()

where Qd is the market quantity demanded and P is the market price in dollars.

The market supply curve is

![]()

where Qs is the market quantity supplied and P is the market price in dollars.

In order to determine the equilibrium price, you take the following steps:

1. Set quantity demanded equal to quantity supplied.

![]()

2. Combine similar terms.

![]()

3. Divide both sides of the equation by 35,000 to solve for P.

![]()

Thus the market-determined equilibrium price is $80.00. This is the price your firm must charge in a perfectly competitive market. If you charge $80.01, nobody will buy your product because they can purchase it from any one of a large number of other firms for $80.00. And you don’t want to charge $79.99, because you can sell everything you produce for $80.00. You have no need to settle for a penny less.

Maximizing profit with total revenue and total cost

Total revenue equals price multiplied by the quantity sold, or

![]()

In this equation, P represents the commodity’s price as determined by supply and demand in the market. For a perfectly competitive market, this price is a constant — it doesn’t change regardless of the quantity of output produced by your firm. You must determine the quantity of output, q0, that maximizes your firm’s profit given the market price P.

In Figure 9-1, total revenue is illustrated as an upward-sloping straight line. Because your firm is a price taker in perfect competition, the slope of the total revenue function is a constant and corresponds to the market-determined price.

Figure 9-1: Profit maximization with total revenue and total cost.

As I explain in Chapter 8, total cost has two components — total fixed cost and total variable cost. Total fixed cost is a constant, so even if your firm shuts down and produces zero units of output, it still incurs total fixed cost. In Figure 9-1, total fixed cost corresponds to the point where the total cost curve intersects the vertical axis at TFC.

As the quantity of output produced increases, total cost increases at a decreasing rate. This fact indicates the total cost curve is becoming flatter due to diminishing returns. Inevitably, however, total cost begins increasing at an increasing rate; or, in other words, the total cost curve becomes steeper, as illustrated in Figure 9-1.

Total profit equals total revenue minus total cost, or

![]()

Total profit is maximized at the output level where the difference between total revenue and total cost is greatest. In Figure 9-1, this occurs at the output level q0. At the output level q0, total revenue equals TR0, total cost equals TC0, and total profit is the difference between them. On the graph, total profit, π, is the vertical distance between TR0 and TC0, and this vertical distance is at its greatest at q0.

![]()

The explicit costs plus implicit costs include every cost associated with production, including the opportunity cost of your time and financial investment. Therefore, if economic profit equals zero, you stay in business. Zero economic profit means you’re receiving exactly as much income in this situation as you will in your next best alternative.

Maximizing total profit with calculus

You can also determine maximum profit by using calculus. In this case, you simply take the derivative of total profit with respect to quantity in order to determine the profit-maximizing quantity of output. Using equations and calculus to maximize profit enables you to avoid “eyeballing” a graph, trying to determine where the difference between total revenue and total cost is greatest.

![]()

Your total cost function is

![]()

Therefore, your total profit equation is

![]()

In order to determine the profit maximizing quantity, you take the following steps:

1. Take the derivative of total profit with respect to quantity.

![]()

2. Set the derivative equal to zero and solve for q.

![]()

3. Divide both sides of the equation by 0.1.

![]()

Thus, 700 units of the good is the profit-maximizing quantity.

4. To determine total profit, simply substitute 700 for q in the total profit equation.

![]()

Total profit equals $12,000.

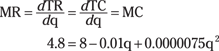

Maximizing profit as a marginal decision

To maximize profit by using marginal revenue and marginal cost, you focus on the contribution one additional unit of output makes to your revenue relative to its contribution to your cost.

Marginal revenue is the change in total revenue that occurs when one additional unit of output is produced. Thus,

![]()

This equation indicates that marginal revenue is the slope of the total revenue function.

As I note in Chapter 8, marginal cost is the change in total cost that occurs when one additional unit of output is produced.

![]()

So, marginal cost is the slope of the total cost equation.

In order to maximize profit, you want to maximize the difference between total revenue and total cost. Thus, if your marginal revenue is greater than your marginal cost (MR>MC), an additional unit of output adds more to your firm’s revenue than it adds to your firm’s cost, and the additional unit earns you more profit.

On the other hand, if your marginal revenue is less than your marginal cost (MR<MC), then the additional unit adds less to your revenue than it adds to your cost, and your profit decreases.

Figure 9-2 indicates the profit-maximizing quantity of output by using marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

Figure 9-2: Profit maximization with marginal revenue and marginal cost.

The marginal revenue curve in Figure 9-2 is horizontal because you can sell every unit you produce at the prevailing market price. Thus, price equals marginal revenue or

![]()

This equation also represents the firm’s demand curve, d, because if the firm charges a price one cent higher than P nobody will buy its product and the quantity demanded equals zero. However at the price P, the firm can sell everything it produces.

The firm’s marginal cost curve is eventually upward-sloping, passing through the minimum points on the average-variable-cost and average-total-cost curves. (For a detailed explanation of these relationships, see Chapter 8.)

The output level where marginal revenue and marginal cost intersect, q0, is the profit-maximizing quantity of output. This output level is exactly the same as the output level q0 determined in Figure 9-1 by using total revenue and total cost.

If your firm produces output at a level less than q0, such as qA, those units add more to your revenue than they add to your cost because marginal revenue is greater than marginal cost. Those units, by adding more to your revenue than they add to your cost, cause your profit to increase. Therefore, you want to increase production and move toward q0.

If your firm produces output beyond q0, say qB, those units add more to your cost than they add to your revenue because marginal cost for those units is greater than marginal revenue. By adding more to your cost than they add to your revenue, those units cause your profit to be lower. So, you want to decrease production and move back toward q0.

Using calculus to find marginal revenue equals marginal cost

You can determine marginal revenue and marginal cost with calculus. Marginal revenue is the change in total revenue; thus it’s represented as the derivative of total revenue taken with respect to the quantity of output or

![]()

Similarly, marginal cost is the change in total cost, so it’s represented as the derivative of total cost taken with respect to the quantity of output produced

![]()

As previously indicated in Figure 9-2, the profit-maximizing quantity of output is determined where marginal revenue equals marginal cost.

![]()

Marginal revenue equals the derivative of total revenue taken with respect to quantity or

![]()

Again note that marginal revenue and price are the same in perfect competition.

If your total cost function is

![]()

Marginal cost equals

![]()

In order to determine the profit-maximizing quantity of output, you simply set marginal revenue or price equal to marginal cost and solve for q.

1. Set marginal revenue equal to marginal cost.

![]()

2. Solve for q.

![]()

The profit maximizing quantity of output is 700 units. Note this is the same answer you obtain when you maximize the total profit equation by using calculus.

Calculating economic profit

After you determine the profit-maximizing quantity of output, you want to determine how much profit you make. Using total revenue and total cost, your total profit is easily calculated by subtracting total revenue from total cost. However, determining the profit-maximizing quantity of output by using marginal revenue and marginal cost doesn’t directly provide you with a measure of total profit.

In this situation, total profit is determined by first calculating your profit per unit of output and then multiplying that amount by the profit-maximizing quantity of output. Profit per unit equals price minus average total cost, or

![]()

Total profit is determined by multiplying profit per unit by the quantity of output produced

![]()

In Figure 9-2, profit per unit is represented by the double-headed arrow between price and average total cost at the output level q0.

![]()

and

![]()

Given these equations, you determine the profit-maximizing quantity is 700 units of the good given the market-determined price of $80. In order to determine the profit per unit and total profit, you take the following steps:

1. Determine the average total cost equation.

Average total cost equals total cost divided by the quantity of output.

![]()

2. Substitute the profit-maximizing quantity of 700 for q to determine average total cost.

![]()

3. Calculate profit per unit.

![]()

or profit per unit equals $17.143.

4. Determine total profit by multiplying profit per unit by the profit-maximizing quantity of output.

![]()

or total profit equals $12,000.

Making the best of a bad situation by minimizing losses

To this point, I’ve used situations where the firm is earning positive profit. Of course it isn’t always the case that the firm’s profit is positive. Nevertheless, firms may continue producing in the short run in order to minimize losses. It’s important to remember that firms who shut down in the short run still have production costs — total fixed cost can’t be changed. Thus, if a firm loses less money than total fixed cost by producing in the short run, the firm should continue production in order to minimize losses.

Figure 9-3 illustrates a situation where a firm minimizes losses by producing in the short run. The profit-maximizing quantity of output is still determined by equating marginal revenue and marginal cost. The firm produces the profit-maximizing quantity of output q0 at that point. However, because price is less than average total cost at q0, the firm loses money. Its loss per unit equals price minus average total cost. This loss per unit is represented by the double-headed arrow in Figure 9-3.

If instead of producing q0 the firm shuts down, it loses total fixed cost. As I indicate in Chapter 8, total fixed cost equals average fixed cost multiplied by the quantity of output, and average fixed cost equals average total cost minus average variable cost. Thus, in Figure 9-3, the difference between average total cost, ATC0, and average variable cost, AVC0, represents the fixed cost per unit at q0. This difference between average total cost and average variable cost is clearly larger than the difference between price and average total cost. Thus, shutting down and losing your fixed costs is a greater loss than occurs if you produce q0.

Figure 9-3: Producing with economic losses.

![]()

Marginal revenue equals the derivative of total revenue taken with respect to quantity or

![]()

If your total cost function is

![]()

Marginal cost equals

![]()

In order to determine the profit-maximizing quantity of output, you simply set marginal revenue or price equal to marginal cost and solve for q.

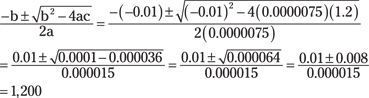

1. Set marginal revenue equal to marginal cost.

2. Solve for q.

Use either a calculator or the quadratic formula.

![]()

The profit maximizing quantity of output is 1,200 units.

3. Determine the average total cost equation.

Average total cost equals total cost divided by the quantity of output.

4. Substitute the profit-maximizing quantity of 1,200 for q to determine average total cost.

5. Calculate profit per unit.

![]()

or profit per unit equals –$3.4875.

6. Determine total profit by multiplying profit per unit by the profit-maximizing quantity of output.

![]()

or total profit equals –$4,185. Your firm is losing $4,185. But note that if you immediately shut down, your losses equal total fixed cost, which is $5,625. Losing $4,185 is a bad situation, but losing $5,625 is even worse. Continuing production makes the best of a bad situation.

Giving up and shutting down

There is a point where you should immediately give up and shut down. But first remember that going out of business in the short run doesn’t mean that your losses go to zero. Because some of the inputs you employ are fixed, going out of business in the short run means you lose your fixed costs. Therefore, if you can make enough revenue to cover all your variable costs (see the previous section), you should stay in business in the short run in order to minimize your losses. However, given your goal is to maximize profits — or, in a bad situation, minimize losses — you should immediately shut down if your revenue doesn’t cover your variable costs. Producing when your revenue is less than your variable costs means that your losses associated with the profit-maximizing quantity of output are greater than your fixed costs. You’re better off shutting down and losing only your fixed costs.

In Figure 9-4, the profit-maximizing quantity of output, based on marginal revenue equals marginal cost, is q0. If you produce this quantity of output, your loss per unit equals price minus average total cost or the distance represented by the double-headed arrow in Figure 9-4. However, your fixed cost is represented by the vertical distance between average total cost, ATC0, and average variable cost, AVC0. Because this distance is less than the loss represented by the double-headed arrow, you’ll lose less money by shutting down — producing zero units of output — and limiting your losses to total fixed cost.

Figure 9-4: Shutting down and limiting losses to total fixed cost.

![]()

Marginal revenue equals the derivative of total revenue taken with respect to quantity, or

![]()

If your total cost function is

![]()

Marginal cost equals

![]()

Again, to determine the profit-maximizing quantity of output, set marginal revenue or price equal to marginal cost.

1. Set marginal revenue equal to marginal cost.

2. Solve for q by using the quadratic formula.

![]()

The profit-maximizing quantity of output is 800 units.

3. Determine the average-total-cost equation.

Average total cost equals total cost divided by the quantity of output.

4. Substitute the profit-maximizing quantity of 800 for q to determine average total cost.

5. Calculate profit per unit.

![]()

or profit per unit equals –$7.83125.

6. Determine total profit by multiplying profit per unit by the profit-maximizing quantity of output.

![]()

or total profit equals –$6,265. By producing 800 units of output where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, your firm is losing $6,265. But note that if you immediately shut down, your losses equal total fixed cost, which is only $5,625. Losing $5,625 is a bad situation, but losing $6,265 is even worse. Shutting down immediately becomes your best option for minimizing your losses.

Disappearing Profit in the Long Run

The long run is a period of time in which all inputs you employ are variable. Therefore, the perfectly competitive firm operating in the long run can change the quantity employed of any input — fixed inputs don’t exist.

Perfect competition has two important characteristics that influence the long-run equilibrium: easy entry and exit and the firm is a price taker.

![]() Easy entry and exit: Firms have no difficulty moving into or out of a perfectly competitive market.

Easy entry and exit: Firms have no difficulty moving into or out of a perfectly competitive market.

![]() Price taker: Individual firms can’t set price, but they can sell everything they produce at the price established by the market.

Price taker: Individual firms can’t set price, but they can sell everything they produce at the price established by the market.

Motivating entry and exit: Where did all your profit go?

Remember that economic profit is based on all production costs; therefore, zero economic profit represents a normal rate of return for your business. If economic profit is greater than zero, your business is earning something greater than a normal return. This profit attracts other firms to enter the market. Similarly, if initial economic losses (negative economic profit) exist, firms leave the market. In the long run, economic profit ultimately equals zero.

Determining the long-run equilibrium

Profit maximization depends on producing a given quantity of output at the lowest possible cost, and the long-run equilibrium in perfect competition requires zero economic profit. Therefore, firms ultimately produce the output level associated with minimum long-run average total cost. In Chapter 8 I tell you that marginal cost must pass through the minimum point of average total cost. Therefore, in the long-run equilibrium, price equals three costs: minimum long-run average total cost, LRATC; the minimum point on one short-run average-total-cost curve, SRATC; and marginal cost, MC.

Figure 9-5 illustrates the long-run equilibrium in perfect competition. The left diagram in Figure 9-5 illustrates the equilibrium price, PE, being determined by the intersection of demand and supply in the market. The perfectly competitive firm is a price taker, so this price is the firm’s marginal revenue curve, P = MR = d, in the right diagram. This price also corresponds to minimum long-run average total cost to ensure zero economic profit in the long run. Thus, new firms have no incentive to enter the market, and existing firms have no incentive to leave the market. Price or marginal revenue equals marginal cost at q0, ensuring that profit is maximized.

![]()

Figure 9-5: Long-run equilibrium in perfect competition.

The long-run equilibrium requires that both average total cost is minimized and price equals average total cost (zero economic profit is earned). In order to find the long-run quantity of output produced by your firm and the good’s price, you take the following steps:

1. Take the derivative of average total cost.

Remember that 12,500/q is rewritten as 12,500q-1 so its derivative equals –12,500q-2 or 12,500/q2.

![]()

2. Set the derivative equal to zero and solve for q.

or average total cost is minimized at 500 units of output.

3. Determine the long-run price.

Remember that zero economic profit means price equals average total cost, so substituting 500 for q in the average-total-cost equation equals price.

![]()

The long-run equilibrium price equals $60.00. So the firm earns zero economic profit by producing 500 units of output at a price of $60 in the long run.

Firms have no difficulty moving into or out of a perfectly competitive market. If economic profit is greater than zero, your business is earning something greater than a normal return. This profit attracts other firms to enter the market. This situation is illustrated in Figure 9-6. At the initial price PA, your firm maximizes profits at qA based on marginal revenue equals marginal cost. At qA, your firm earns positive profit because price is greater than average total cost. This profit provides incentive for new firms to enter the market, increasing the market supply from SA to SLR. The entry of new firms results in a lower equilibrium price for the good, PLR. As price decreases, your profit-maximizing quantity moves to qLR and your economic profit moves toward zero because price now equals average total cost. When economic profit reaches zero, no one has any incentive for entry or exit.

Figure 9-6: Moving from positive to zero profit.

Similarly, if initial economic losses — negative economic profit — exist, firms leave the market, moving the perfectly competitive market to its long-run equilibrium. This situation is illustrated in Figure 9-7. The loss of firms decreases supply from SB to SLR, resulting in upward pressure on price, from PB to PLR. With the increase in price, your firm’s profit-maximizing quantity increases from qB to qLR, and zero economic profit is reached because the price PLR now equals average total cost.

Figure 9-7: Moving from negative to zero profit.

So no matter where you start, in perfect competition your economic profit ultimately becomes zero. And at this point, Yogi Berra might say it’s over.

The best examples of perfectly competitive markets are markets for agricultural commodities, such as wheat, corn, and soybeans. In these markets, a large number of firms — farmers — produce a standardized commodity — corn is the same no matter who grows it — in a market characterized by relatively easy entry and exit — farmland is bought and sold rather easily — and perfect information — such as on the Chicago Board of Trade.

The best examples of perfectly competitive markets are markets for agricultural commodities, such as wheat, corn, and soybeans. In these markets, a large number of firms — farmers — produce a standardized commodity — corn is the same no matter who grows it — in a market characterized by relatively easy entry and exit — farmland is bought and sold rather easily — and perfect information — such as on the Chicago Board of Trade. Because the individual firm can sell any quantity of output at the prevailing market price, the demand for an individual firm’s output is perfectly elastic or horizontal. Therefore, each additional unit of the commodity the firm sells adds the prevailing market price to total revenue, or, marginal revenue equals price.

Because the individual firm can sell any quantity of output at the prevailing market price, the demand for an individual firm’s output is perfectly elastic or horizontal. Therefore, each additional unit of the commodity the firm sells adds the prevailing market price to total revenue, or, marginal revenue equals price.

Economists use the terms

Economists use the terms