Chapter 11

Oligopoly: I Need You

In This Chapter

![]() Competing with a few rivals

Competing with a few rivals

![]() Recognizing mutual interdependence

Recognizing mutual interdependence

![]() Developing theories for anticipating rival behavior

Developing theories for anticipating rival behavior

![]() Prospering in the long run

Prospering in the long run

I Need You is a popular song first performed by the Beatles. The lyrics describe how one person doesn’t realize how much he needs another with one lyric being “see just what you mean to me.” Well, in oligopoly, rival firms make decisions that impact or mean something to one another. Oligopolies need rivals.

Oligopolies have a small number of firms. As a result, you know that your rivals and their actions directly impact you and everybody else’s firm operating in that market. The result is mutual interdependence among firms. You need to understand how your rivals respond to your decisions, and responses can vary. Because anticipating reactions is difficult, no single theory describes oligopolistic markets. Several theories are needed to cover the range of possible behaviors.

In this chapter, I start by describing the characteristics of oligopoly. Understanding these characteristics helps you recognize when you must anticipate rival behavior. Next, I develop different models describing how various reactions affect your decisions and profits. For each of these models, I summarize the circumstances that make it the appropriate explanation for firm behavior helping you to choose when to use the model. I finish the chapter by examining how you maintain profit over an extended period of time.

So, as the song says, I need you. But I don’t want to need too many others, because keeping the number of rivals small enables me to enjoy profit for a long time.

Managing with a Few Rivals in Oligopoly

Oligopolistic markets are easily recognized by the small number of firms that dominate the market. Because there are very few rivals, everybody knows everything about everybody else. It’s sort of like living in a small town. Although this description may seem a little extreme, I’m not exaggerating by much. Examples of oligopolistic markets include the airline, steel, and automobile industries.

Identifying oligopolies

Oligopolies have two major characteristics.

![]() Small number of firms: Oligopolistic markets are dominated by a small number of firms. Each firm provides a fairly large percentage of the total quantity of the good available in the market. Therefore, individual firms have some degree of monopoly power and are able to set the good’s price.

Small number of firms: Oligopolistic markets are dominated by a small number of firms. Each firm provides a fairly large percentage of the total quantity of the good available in the market. Therefore, individual firms have some degree of monopoly power and are able to set the good’s price.

![]() Barriers to entry: Barriers to entry ensure the continued dominance of a small number of firms. Barriers to entry also enable oligopolistic firms to maintain positive economic profit, or returns in excess of the normal rate of return, in the long run. Barriers to entry typically result from economies of scale. The presence of economies of scale leads to larger firms having lower production cost per unit. Smaller new firms with fewer customers and lower production levels find it difficult to match the lower per-unit production costs of the existing firms.

Barriers to entry: Barriers to entry ensure the continued dominance of a small number of firms. Barriers to entry also enable oligopolistic firms to maintain positive economic profit, or returns in excess of the normal rate of return, in the long run. Barriers to entry typically result from economies of scale. The presence of economies of scale leads to larger firms having lower production cost per unit. Smaller new firms with fewer customers and lower production levels find it difficult to match the lower per-unit production costs of the existing firms.

Living with mutual interdependence

Because of their small number, oligopolistic firms regard themselves as mutually interdependent. The actions of any one firm influence all other firms operating in the market. Oligopolistic firms must take into account how rivals respond to their actions.

Yikes! Mutual interdependence means you have to take into account how your rivals respond to your decisions, and there are only about a gazillion ways they might respond. This potential number of responses isn’t a big problem for economists. They don’t mind developing a gazillion theories. But for you it’s a problem — unless, of course, you don’t mind learning a gazillion theories.

The key point is that oligopolistic markets can’t be described with a single theory like perfect competition and monopoly. (See Chapters 9 and 10 for details on perfect competition and monopoly, respectively.) Thus, I present several different theories that describe firm profit-maximizing behavior. With each of these theories, pay close attention to the way rivals respond to your decisions. Your understanding of rivals and how they respond determines which theory is appropriate.

Finally, mutual interdependence introduces the possibility of collusion among oligopolistic firms. Collusion occurs when firms act jointly in setting price and quantity. It typically isn’t legal to collude in the United States, although a few exceptions, such as Major League Baseball, exist.

Engaging in advertising and non-price competition

Another method of discouraging entry to the market is to increase advertising. Advertising not only increases visibility and brand loyalty for an existing firm’s product, but it also makes it more difficult for new firms to attract potential customers. Advertising enables you to increase the demand for your product by attracting new customers and “stealing” current customers from rival firms.

Oligopolies also innovate to separate themselves from rivals. Innovations that improve product quality or result in a better product to satisfy the same consumer desires increase the firm’s demand and profits. Innovation can also increase profit by lowering the firm’s production costs.

Modeling Oligopoly Behavior

In this section, I present six theories for oligopoly behavior. I know six is a lot, so you may want to skip some. But also, remember, I’m trying to anticipate how rivals respond and guessing how others react is risky business.

Sticking with sticky prices

The theory of the kinked demand curve is used to explain price inflexibility in an oligopolistic market. This theory is used when prices change very rarely — or in other words, prices are sticky.

The theory stresses mutual interdependence by describing how firms respond to any price change your firm may make. If your firm lowers price, the theory assumes that everyone lowers price to avoid losing customers and market share. So, if you lower price, you won’t sell much more. On the other hand, if you raise price, none of your rivals will raise price. As a result, many of your customers will switch to one of your rivals. You’ll lose a lot of sales.

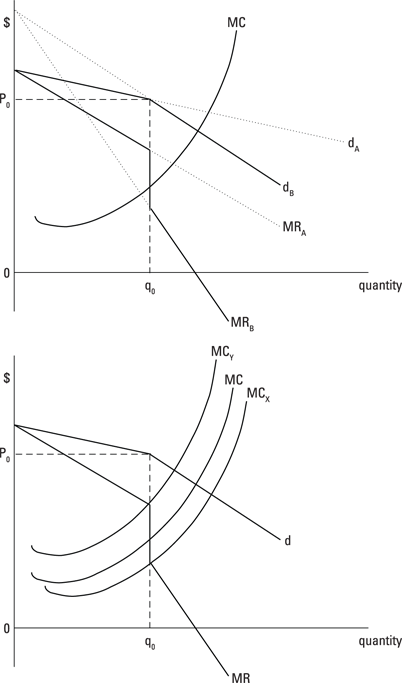

Figure 11-1 portrays the situation that exists with a kinked demand curve. The top panel of the graph illustrates the demand curve your firm faces. The current profit-maximizing quantity and price are q0 and P0, respectively. Note that the profit-maximizing quantity corresponds to marginal revenue intersects marginal cost, and price is determined based upon where the quantity q0 hits the demand curve.

If your firm decreases price, you assume that all your rivals will also decrease their price in order to avoid losing customers. The portion of your firm’s demand curve associated with a price decrease is less elastic. Your demand curve is steeper and quantity demanded is less responsive to a decrease in price. That’s because your firm is unable to steal customers from rival firms that also lower their product’s price. This less-elastic demand is represented by the steeper curve labeled dB in the upper panel of Figure 11-1. Because this demand curve is relevant only for price decreases and quantities above q0, it’s a solid line only for prices below P0. (The dotted section of the line for prices above P0 isn’t relevant.)

The marginal revenue curve associated with dB is the steeper curve labeled MRB. Again, only the portion of the marginal revenue curve above q0 is relevant and illustrated with a solid line.

If your firm increases price, you assume none of your rivals increase their prices. Your customers are likely to switch to buying the product from your rivals that are relatively cheaper after your price increase. The portion of your firm’s demand curve above P0 is likely to be more elastic; quantity demanded is more responsive to a price increase. This segment of the firm’s demand curve is represented by the flatter line dA above P0 and to the left of q0.

The marginal revenue curve associated with dA is the flatter curve labeled MRA.

The kink in the firm’s demand curve at P0 and q0 introduces a discontinuity in the marginal revenue curve. The solid segments of the marginal revenue curves MRA and MRB don’t touch. This discontinuity is connected by the solid vertical segment in the marginal revenue curve.

Figure 11-1: The kinked demand curve.

The bottom panel of Figure 11-1 illustrates why prices are sticky. The kinked demand curve and its resulting marginal revenue curve are the same as derived in the upper panel. The profit-maximizing quantity based on marginal revenue intersects marginal cost is q0 and going from that quantity up to the demand curve leads to the profit-maximizing price P0.

What’s critical to note is that the marginal revenue curve resulting from the kinked demand curve has a vertical region. Thus, if marginal cost shifts anywhere in that vertical region — anywhere between the marginal cost labeled MCx to the curve labeled MCY — the profit-maximizing quantity and price don’t change. Price doesn’t change in response to shifts in the marginal cost curve — hence price is sticky. Given price’s inflexibility, firms in this situation must rely more heavily on non-price competition.

Reacting to rivals in the Cournot model

Oligopolies commonly compete by trying to steal market share from one another. Thus, rather than compete by lowering price — the kinked demand curve (see the previous section) indicates that this tactic doesn’t work because everyone lowers price — firms often compete on the other factor that directly affects profit — the quantity of the good they sell.

The Cournot model is used when firms produce identical or standardized goods and don’t collude. Each firm assumes that its rivals make decisions that maximize profit.

The Cournot duopoly model offers one view of firms competing through the quantity produced. Duopoly means two firms, which simplifies the analysis. The Cournot model assumes that the two firms move simultaneously, have the same view of market demand, have good knowledge of each other’s cost functions, and choose their profit-maximizing output with the belief that their rival chooses the same way. With all these assumptions, you may wonder why not just assume the right answer. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way. On the other hand, you may think that these assumptions are unrealistic. However, research has shown that decision-makers operating in the same market over an extended period of time tend to have similar views of market demand and good knowledge of one another’s cost structure.

Given these assumptions, one firm reacts to what it believes the other firm will produce. In other words, if firm B produces qB of output, what quantity should I have my firm — firm A — produce? The Cournot reaction function describes the relationship between the quantity my firm produces and the quantity my rival produces. Here’s how it works.

![]()

where QD is the market quantity demanded and P is the market price in dollars.

Assuming firm A has a constant marginal cost of $20 and firm B has a constant marginal cost of $34, the reaction function for each firm is derived by using the following steps:

1. Note that the market quantity demand, QD, must be jointly satisfied by firms A and B.

Thus,

![]()

2. Substituting the equation in Step 1 for QD in the market demand curve yields

![]()

3. For firm A, total revenue equals price multiplied by quantity.

![]()

4. Firm A’s marginal revenue is determined by taking the derivative of total revenue, TRA, with respect to qA.

Remember to treat qB as a constant because firm A can’t change the quantity of output produced by firm B.

![]()

5. Firm A maximizes profit by setting its marginal revenue equal to marginal cost.

Firm A’s marginal cost equals $20.

![]()

6. Rearranging the equation in Step 5 to solve for qA gives firm A’s reaction function.

![]()

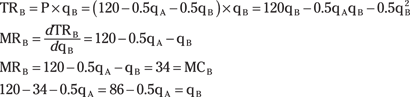

7. Repeat Steps 3 through 6 to determine firm B’s reaction function.

Remember that firm B’s marginal cost equals $34.

8. Substituting firm B’s reaction function for qB in firm A’s reaction function enables you to solve for qA.

9. Substituting qA = 76 in firm B’s reaction function enables you to solve for qB.

![]()

Thus, in the profit maximizing Cournot duopolist, firm A, produces 76 units of output while firm B produces 48 units of output. Figure 11-2 illustrates this result.

Figure 11-2: A Cournot duopoly.

In the last example, firms A and B had different marginal costs. If the firms have the same marginal costs (MCA = MCb), each firm produces half the market output.

Leading your rivals with the Stackelberg model

Changing the assumptions of how firms react to one another changes the decision-making process. In the Stackelberg model of duopoly, one firm serves as the industry leader. As the industry leader, the firm is able to implement its decision before its rivals. Thus, if firm A makes its decision first, firm A is the industry leader and firm B reacts to or follows firm A’s decision. However, in making its decision, firm A must anticipate how firm B reacts to that decision. An example of such leadership may be Microsoft’s dominance in software markets. Although Microsoft can make decisions first, other smaller companies react to Microsoft’s actions when making their own decisions. The actions of these followers, in turn, affect Microsoft.

The market demand curve now faced by the Stackelberg duopolies is:

![]()

where QD is the market quantity demanded and P is the market price in dollars.

I continue assuming that firm A has a constant marginal cost of $20 and firm B has a constant marginal cost of $34. Derive the Stackelberg solution with the following steps:

1. Firms A and B provide the entire market quantity demand, QD.

Thus,

![]()

2. Substitute qA and qB for QD in the market demand curve to yield

![]()

3. Because firm B reacts to firm A’s output decision, I begin by deriving firm B’s reaction function.

Start by noting that total revenue equals price multiplied by quantity. For price, I substitute the equation from Step 2.

![]()

4. Firm B’s marginal revenue equals the derivative of total revenue, TRB, with respect to qB.

Treat qA as a constant because firm B can’t change the quantity of output produced by firm A.

![]()

5. Firm B maximizes profit by equating its marginal revenue and marginal cost.

Remember that firm B’s marginal cost equals $34.

![]()

6. Rearrange the equation in Step 5 to solve for qB and to get firm B’s reaction function.

![]()

For the next step, the demand curve faced by firm A is

![]()

7. At this point, substitute firm B’s reaction function into firm A’s demand curve.

This is the critical difference from the Cournot duopoly in the previous section. By substituting firm B’s reaction function in its decision-making process, firm A is anticipating firm B’s reaction to its output decision.

![]()

8. Firm A’s total revenue, TRA, equals price times quantity.

![]()

9. Firm A’s marginal revenue is the derivative of total revenue taken with respect to qA.

![]()

10. Firm A determines the profit-maximizing quantity of output by setting marginal revenue equal to marginal cost and solving for qA.

Remember that firm A’s marginal cost is a constant $20.

![]()

11. Substitute qA into firm B’s reaction function from Step 6 to determine qB.

![]()

Thus, the profit-maximizing Stackelberg duopoly has firm A producing 114 units of output and firm B producing 29 units of output. Figure 11-3 illustrates the Stackelberg duopoly. Note that firm B has exactly the same reaction function as existed in the Cournot duopoly. On the other hand, firm A doesn’t have a reaction function. Firm A sets it output first, and then firm B reacts to that output. Thus, the horizontal line for firm A at 114 units of output indicates it has set its output before firm B reacts.

The simultaneous decision-making associated with the Cournot model leads to different outcomes from the outcomes associated with sequential decisions of the Stackelberg model. In the model examples, I use the same equations for market demand and each firm’s marginal cost. In the Cournot model solution, firm A produces 76 units, and firm B produces 48 units. Thus, the total market output is 124 units. When you substitute these quantities into the market demand curve, the price is $62.00. In the Stackelberg model, firm A produces 114 units, and firm B produces 29 units, and the total market output is 143 units. Substituting these quantities into the market demand curve leads to a price of $48.50. Thus, the Stackelberg leadership model results in a higher market quantity and lower price for the good as compared to the Cournot model.

Figure 11-3: A Stackelberg duopoly.

Competing for customers through the Bertrand model

The Cournot and Stackelberg duopoly theories focus on firms competing through the quantity of output they produce. The Bertrand duopoly model examines price competition among firms that produce differentiated but highly substitutable products. Each firm’s quantity demanded is a function of not only the price it charges but also the price charged by its rival. Coca-Cola and Pepsi are examples of Bertrand duopolists.

![]()

To simplify the analysis, I assume that both firms have zero marginal cost for their products. Profit maximization then requires each firm to choose a price that maximizes its total revenue.

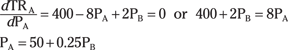

Derive the Bertrand reaction functions for each firm with the following steps:

1. Firm A’s total revenue equals price times quantity, so

![]()

2. Taking the derivative of firm A’s total revenue with respect to the price it charges yields

![]()

3. Setting the equation in Step 2 equal to zero and solving it for PA generates firm A’s reaction function.

Setting the derivative of total revenue equal to zero maximizes total revenue, which also maximizes profit given marginal cost equals zero.

4. Repeat these steps for firm B to derive its reaction function.

5. Substitute firm B’s reaction function into firm A’s reaction to determine PA.

![]()

6. Substitute PA equals 64 in firm B’s reaction function to determine PB.

![]()

The Bertrand duopoly model indicates that firm A maximizes profit by charging $64, and firm B maximizes profit by charging $56. Figure 11-4 illustrates the Bertrand duopoly model. Note that both the horizontal and vertical axes on the figure measure price and not quantity (as in the Cournot and Stackelberg models).

Figure 11-4: A Bertrand duopoly.

Leading the pack: Another view of price leadership

The Stackelberg model of oligopoly illustrates one firm’s leadership in an oligopoly. In the Stackelberg model, the leader decides how much output to produce with other firms basing their decision on what the leader chooses. Another common form of leadership is for the leading firm to set price. Rival firms then use the same price for their products. However, as is always the case in oligopoly, the leading firm must take into account the behavior of its rivals.

The leading firm that initially sets price is called the dominant firm. The firms that use the price set by the dominant firm are typically smaller in size and called following firms. Markets for steel and agricultural implements have been observed to operate in this manner.

Figure 11-5 illustrates price leadership. The market has a downward-sloping demand curve labeled D. A crucial point: The dominant firm must take into account that its following firms satisfy part of that market demand. Because the following firms act as price takers, their marginal revenue curve is the price set by the dominant firm. To maximize profits, the following firms produce where price/marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Therefore, each following firm’s supply curve corresponds to its marginal cost curve, and the aggregate supply curve for all following firms is the horizontal summation of the marginal cost curves. This horizontal summation of marginal cost is represented by the curve ΣMCf.

In Figure 11-5, the dominant firm’s demand curve, dd, is derived from the market demand and the aggregate supply curve for the following firms. The dominant firm simply subtracts the quantity provided by the following firms from the quantity demanded in the market to determine its quantity demanded. In other words, the dominant firm’s demand curve equals the market demand curve minus the sum of the following firm’s marginal cost curves, ΣMCf.

Given the linear relationships in Figure 11-5, the dominant firm’s marginal revenue curve, MRd, is twice as steep as its demand curve. The dominant firm maximizes profit by producing the quantity of output that corresponds to marginal revenue, MRd, equals marginal cost, MCd. This output level is qd. The dominant firm determines price by going from the quantity qd up to its demand curve, dd. Thus, the dominant firm sets the price at Pd.

As already noted, following firms are price takers. The dominant firm’s price Pd is the price that all following firms charge for every unit of the product they sell. For the following firms, the dominant firm’s price becomes their marginal revenue, Pd = MRf. The following firms then maximize profit by setting marginal revenue, MRf, equal to marginal cost, MCf. In aggregate, the following firms produce qf of output.

For the market, consumers pay a price of Pd and consume the quantity Q. The quantity consumed Q equals qd plus qf.

![]()

where Q is the market quantity demanded and P is the good’s price in dollars.

Figure 11-5: Price leadership.

The aggregate marginal cost for the following firms is represented by

![]()

where ΣMCf is the horizontal summation of marginal cost for the following firms and qf is the aggregate quantity produced by the following firms.

The dominant firm’s marginal cost curve is

![]()

where MCd is the dominant firm’s marginal cost in dollars and qd is the quantity produced by the dominant firm.

In order to determine the good’s market price and the quantity of the good produced by the dominant firm and the following firms, you take the following steps:

1. Derive the dominant firm’s demand curve.

Note that the market quantity demanded Q equals:

![]()

2. Rearrange the following firms’ aggregate marginal cost curve to get

![]()

3. Substitute P for MCf in the equation from Step 2.

This substitution is allowed because following firms produce where price equals marginal cost in order to maximize profit.

![]()

4. In the Step 1 equation, substitute the market demand equation for Q and the equation for qf from Step 3.

This step generates the equation for the dominant firm’s demand curve.

5. Rearrange the equation in Step 4 to solve for P as a function of qd.

This form is converted to the total revenue equation in the next step.

![]()

6. Determine the dominant firm’s total revenue equation.

Remember, total revenue equals price multiplied by quantity.

![]()

7. Determine the dominant firm’s marginal revenue equation.

Take the derivative of total revenue with respect to qd.

![]()

8. Determine the dominant firm’s profit-maximizing quantity of output.

Set the dominant firm’s marginal revenue equal to the dominant firm’s marginal cost and solve for qd.

![]()

9. Substitute qd equals 800 into the dominant firm’s demand curve in order to determine the price established by the dominant firm.

![]()

The dominant firm produces 800 units of output and charges a price of $14.

10. Determine the following firms aggregate quantity of output.

Following firms are price takers, so the dominant firm’s price is the following firms’ marginal revenue.

![]()

11. Determine the market quantity demanded.

Substitute 14 for price P in the market demand equation.

![]()

So the dominant firm produces 800 units of output at a price of $14. The following firms produce an aggregate of 1,500 units. The market quantity demanded given a price of $14 is 2,300 units — the same as qd plus qf.

Working together by using cartels and collusion

Recognizing that mutual interdependence can lead to undesirable outcomes, firms have an incentive to cooperate by colluding or forming cartels that limit competition. With collusion, rival firms cooperate for their mutual benefit. Although such behavior is generally illegal in the United States, in other parts of the world, collusion is permitted. Airbus, one of the two biggest civilian aircraft manufacturers in the world, arose from a consortium of European companies and, until recent years, collusion among Japanese firms manufacturing auto parts was widespread. A cartel is the result of an open, formal, and legal collusive agreement. Today, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is the most widely recognized cartel “success” story.

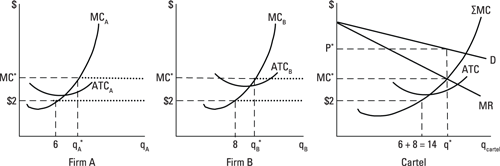

Through collusion, firms act together so their behavior mirrors a monopoly’s behavior. In essence, the firms try to gain monopoly profits by eliminating competition among them. If the cartel’s goal is to maximize the cartel’s total profit, the cartel takes the actions represented in Figure 11-6.

The cartel’s marginal cost is the horizontal summation of the individual firm marginal cost curves. In Figure 11-6, firms A and B have the marginal cost curves MCA and MCB. A marginal cost of $2 is associated with 6 units of output for firm A and 8 units of output for firm B. The horizontal summation of marginal cost means that, for the cartel, a marginal cost of $2 is associated with 14 units of output — 8 plus 6. The cartel’s marginal cost curve is represented by ΣMC.

Figure 11-6: Cartel behavior.

The cartel faces the market demand for the good and, from the market demand, derives marginal revenue. The graph on the far right of Figure 11-6 illustrates the market demand, labeled D, and marginal revenue, labeled MR.

The cartel maximizes its profit by producing the output level associated with marginal revenue equals marginal cost in the far right panel of Figure 11-6. This corresponds to the output level q*. Based upon the profit-maximizing output level, the cartel goes up to the demand curve to determine the profit-maximizing price or monopoly price, P*.

In order to maximize its total profit, the cartel must minimize production cost. In order to minimize production cost, the marginal cost of the last unit produced by each member of the cartel must equal the marginal cost associated with profit maximization — MC* in Figure 11-6. Thus, firm A in Figure 11-6 produces qA* and firm B produces qB*.

Cartels tend to be unstable because members often have incentive to cheat on the arrangement. In Figure 11-6, firm A has an incentive to produce more than qA* because selling more output increases its profit. However, any change in output from qA* reduces the cartel’s combined profit. Thus, if firm A’s profit increases, it must be at another member’s expense — firm B ends up with less profit. The different, conflicting interests of cartel participants lead to instability. And given that collusion is usually illegal, any agreements are legally unenforceable.

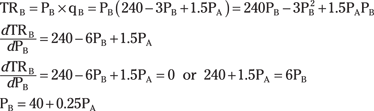

Firm A’s total cost and marginal cost equations are:

where TCA is firm A’s total cost in dollars, MCA is marginal cost in dollars, and qA is the quantity firm A produces.

Firm B’s total cost and marginal cost equations are:

where TCB is firm B’s total cost in dollars, MCB is marginal cost in dollars, and qB is the quantity firm B produces.

The market demand for the good produced by firms A and B is:

![]()

where P is the good’s price in dollars and Q is good’s market quantity demanded.

If firms A and B form a cartel, profit-maximization requires

![]()

By solving this set of equations simultaneously, the cartel’s profit-maximizing quantity of output and price are determined. In addition, the quantity of output each firm produces to minimize production cost is determined.

1. Determine total revenue as a function of quantity.

Because firms A and B are acting together, the market demand curve becomes the cartel’s demand curve. Determine total revenue as a function of quantity by multiplying price from the market demand curve times quantity.

![]()

2. Determine marginal revenue.

To determine marginal revenue, take the derivative of total revenue with respect to Q.

![]()

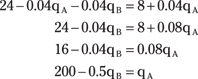

3. Set MR = MCA.

![]()

4. Substitute qA + qB for Q.

Because the total quantity of output the cartel sells, Q, is produced in some combination from firms A and B, the quantities produced by each firm added together must equal the quantity sold by the cartel.

![]()

5. Solve the equation in Step 4 for qA.

6. Set MCA equal to MCB.

![]()

7. Substitute qA = 200 – 0.5qB in the equation in Step 6.

![]()

8. Solve for qB.

![]()

9. Substitute qB = 140 in the equation from Step 5 to determine qA.

![]()

10. Solve for Q, the quantity the cartel produces.

![]()

11. Solve for P, the price the cartel establishes for the good.

![]()

The cartel establishes a price of $18.60 for the good. Firm A produces 130 units and firm B produces 140 units.

Profiting from the Long Run

Economies of scale serve as a barrier to entry in oligopolistic markets. Economies of scale mean that existing firms produce a large quantity of the good at very low average total cost per unit. The existing firms tend to have substantial fixed costs, so producing a larger quantity of output reduces their fixed cost per unit and thus their average total cost per unit. On the other hand, a new firm entering the market isn’t likely to have many customers at first. Therefore, the new firm produces a much smaller quantity of output and can’t spread its fixed costs as far. The result is much higher average total cost per unit for a new firm.

Because their cost per unit is lower than the new firm’s cost per unit, the existing firms charge lower prices than the new firm. Yet, even with the lower price, the existing firms earn positive economic profit because their cost per unit is so low. If the new firm tries to match this low price, it loses money because it has a much higher cost per unit. Thus, even with the attraction of positive profit, new firms can’t effectively compete with existing firms who take advantage of economies of scale.

The market demand curve faced by Cournot duopolies is:

The market demand curve faced by Cournot duopolies is: