APPENDIX C: THE CARKHUFF HELPING MODEL Research Background

Helping Outcomes

Historically, Eysenck (1960) and others (Levitt, 1963; Lewis, 1965) confronted the helping professions with the challenge that counseling and psychotherapy really did not make a difference. About two-thirds of the patients remained out of the hospital a year after treatment, whether or not they were seen by professional psychotherapists. These effects held for adult and child treatment.

One answer to this challenge was the finding that the variability, or range of effects, of the professionally treated groups on a variety of psychological indices was significantly greater than the variability of the “untreated” groups (Rogers, Gendlen, Kiesler, & Truax, 1967; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). This meant that professional practitioners tended to spread their effects on the patients. This suggested one very consoling conclusion: Counseling and psychotherapy really did make a difference. It also suggested one very distressing conclusion: Counseling and psychotherapy have a two-edged effect—they may be helpful or harmful (Bergin, 1971).

Follow-up research by Anthony and his associates (Anthony, Buell, Sharratt, & Althoff, 1972; Anthony, Cohen, & Vitalo, 1978) shed some light on the lasting effects of counseling, rehabilitation and psychotherapeutic techniques. This research was based upon data indicating that within three to five years of treatment 65 percent to 75 percent of the ex-psychiatric patients would once again be patients. Also, regardless of the follow-up period, the gainful employment of ex-patients would be below 25 percent.

The major conclusion drawn from these data on outcome was that counseling and psychotherapy—as traditionally practiced—was effective in about 20 percent of the cases. Of the two-thirds of the clients and patients who initially got better, only one-third to one-quarter stayed better. Multiplied out, this meant that psychotherapy had lasting positive effects in between 17 percent and 22 percent of the cases. Counseling and psychotherapy may indeed be “for better or for worse.” In most instances, the lasting effects are not facilitative.

In order to understand the reasons for these outcomes, we examined the process of counseling and psychotherapy. When we looked at effective helping processes from the perspective of the helpee, we found that helping is simply a learning or relearning process leading to change or gain in the behavior of the helpee (Bergin, 1971; Carkhuff, 1969).

Learning Processes

The phases of effective counseling and psychotherapy are really the phases of effective learning (Carkhuff, 1969, 1971a; Carkhuff & Berenson, 1967, 1977). The helping processes by which helpees are facilitated or retarded in their development involve their exploring where they are in their worlds; understanding and specifying where they want to be; and developing and implementing step-by-step action programs to get there.

Exploring is a pre-condition of understanding, giving both helper and helpee an opportunity to get to know the helpee’s experience of where he or she is in the world. In this respect, exploration is a self-diagnostic process for the helpee. Exploration is in part under the control of the helper and in part under the control of the helpee. High-level functioning helpees explore themselves independent of the level of interpersonal skills offered by the helpers while moderate to low-level functioning helpees are dependent upon the helper’s skills for their level of exploration (Carkhuff & Berenson, 1976).

Understanding is the necessary mediational process between exploring and acting (Carkhuff & Berenson, 1976). It serves to help the client focus upon personalized goals made available through exploration. The basic foundation for understanding rests with insights—insights revealing the helpee’s own deficits and role in the situation—which increase the probability that related behaviors will occur. Unfortunately, action does not always follow insight. For one thing, insights promoted by “common sense” techniques are usually neither developed systematically (in such a way that each piece of explored material is used as a base for the next level of understanding) nor with specificity as observable, measurable, repeatable behavior; therefore, the individual helpee, aided only by common sense, does not “own” the insights and cannot act upon them.

Acting is the necessary culminating process of helping (Carkhuff & Berenson, 1976). The helpees must act upon their newly personalized understanding in order to demonstrate a change or gain in their behavior. In doing so, they are provided with the opportunity to acquire new experience and thus stimulate more extensive exploration, more accurate understanding, and more effective action. Any discrepancy between understanding and acting is, in part, a function of the lack of systematically developed action programs that flow from systematically developed insights.

In conclusion, both helpers and helping programs are effective in facilitating the helping process to the degree that they incorporate and emphasize the phases of learning: involving the helpees in exploring where they are in their worlds; understanding and specifying goals for where they want or need to be; and developing and implementing step-by-step action programs to achieve their goals. The helpers who have the helping skills and the skills to develop helping programs are, for the most part, those individuals who have learned them in systematic skills-training programs, whether professional or paraprofessional (Anthony & Carkhuff, 1978; Carkhuff, 1968).

The number of models of helping based upon this simple paradigm of helping as learning have proliferated in the literature of counseling and psychotherapy (Anthony, 1979; Brammer, 1973; Combs, Avila, & Purkey, 1978; Danish & Hauer, 1973; Egan, 1975, 1990; Gazda, 1973; Goodman, 1972; Guerney, 1977; Ivey & Authier, 1978; Kagan, 1975; Patterson, 1973; Schulman, 1974). Through varying their terminology, most attribute the effectiveness of counseling and psychotherapy to those helper skills that facilitate the helpee’s self-exploration. None of these helping approaches has identified and operationalized the helper dimensions of personalizing that culminate in helpee action and behavior change. Indeed, most major therapeutic orientations tend to emphasize exclusively one phase of helping or the other.

And what about the ‘‘common sense” approach to helping that is employed by the well-intentioned, yet unskilled helper? Perhaps the best illustration of the potential dangers and harm of the ‘‘common sense” approach are several research studies that investigated the helping skills of untrained hot-line volunteers (Carothers & Inslee, 1974; Augelli, Handis, Brumbaugh, Illig, Shearer, Turner & Frankel, 1978; Genther, 1974; Rosenbaum & Calhoun, 1977; Schultz, 1975). Volunteers such as these would certainly seem to be concerned and well-intended. Yet despite such assumptions, the research suggests that untrained volunteers do not normally possess a high level of helping skills to combine with their good intentions. In order to be effective, helpers must combine their good intentions with helping skills; for it is the helper’s skills that make the difference. Concern is clearly not enough. None of this is intended to imply that volunteers or other types of noncredentialed helpers cannot be expert in the skills of helping. As a matter of fact, uncredentialed helpers who have buttressed their good intentions with a training program in helping skills can be as helpful or more helpful than the typical credentialed professional (Anthony & Carkhuff, 1978; Carkhuff, 1968).

Attending Skills

At the pre-helping or involvement stage of helping, the helping skills are essentially nonverbal. Except for the preliminary attending skills of informing and encouraging, these are all skills that the helper does “without opening his or her mouth.” Perhaps because of the lack of verbal involvement, these attending skills are sometimes considered to be relatively simple and unimportant. Yet a number of research investigations suggest that these skills are more potent and more complex than is generally believed (Barker, 1971; Birdwhistell, 1967; Carkhuff, 1969; Ekman, Friesen, & Ellsworth, 1972; Hall, 1959, 1976; Ivey & Authier, 1978; Mehrabian, 1972; Schefflen, 1969; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967).

Getting and Keeping the Helpee Involved

It would seem that helpee involvement in the helping process should be a foregone conclusion. After all, helping is for the helpee—why not become involved? Unfortunately, significant data exist that indicate the helpee involvement is far from the norm (McClurek, 1978), suggesting, perhaps, that the helpee may not perceive helping as being totally for his or her own benefit.

For example, one study reported data that indicated that as many as 66 percent of the patients referred from a psychiatric hospital to a community-based rehabilitation center chose not to attend the center (Wolkon, 1970). In addition, only half of those persons who began the program attended more than ten times. Other researchers have summarized data that indicated that a large number of clients prematurely drop out of counseling and psychotherapy of their own volition (Garfield, 1971). One such study found that of the 13,450 clients seen in nineteen community mental health facilities, approximately 40 percent terminated treatment after only one session, and that the dropout rate for the nonwhite clients was significantly higher (Sue, McKinney, & Allen, 1976; Sue, McKinney, Allen, & Hall, 1974). Clearly, helpee involvement in the helping process cannot be taken for granted.

Positioning, Observing and Listening

Some researchers (Genther & Moughan, 1977; Smith-Hanen, 1977) have investigated how different aspects of the helper’s positioning skills affect how the helper is evaluated by the helpee. For example, Smith-Hanen (1977) found that certain leg and arm positions of the counselor do affect the helpee’s judgment of counselor warmth and empathy. Genther and Moughan (1977) examined the effect of the counselor’s forward leaning (incline) on the helpee’s rating of attentiveness. In all instances, the helper in the forward-leaning position was evaluated by the helpees as more attentive than the helper in an upright posture.

Additional research suggests that, besides attempting to get and keep the helpee involved, the positioning skills of the helper are also important because of their critical relationship to observing skills (Carkhuff, 1969). This relationship between helper positioning and observing skills is apparent in several key ways. First, an attentive posture and an appropriate environment facilitate observing, primarily by reducing the observer’s possible distractions. Second, by making observations of a helpee’s attending position, a helper can draw possible inferences about the helpee’s feeling state and energy level. Third, positioning oneself so that you can pay attention to people can make people more nonverbally expressive, eliciting more nonverbal material to observe and more verbal material to which to listen and from which to make inferences.

Research findings in the area of verbal and nonverbal communication support the contention that there is a relationship between positioning, observing and listening skills (Barker, 1971; Mehrabian, 1972). Just as the helper’s observing skills are in part a function of her or his positioning skills, a helper’s listening skills are related to the skillfulness with which he or she positions himself or herself and observes. As a matter of fact, observing can be conceived of as a type of nonverbal listening. A person who demonstrates that she or he is listening nonverbally (observing) will increase the verbal output of the speaker. Additional research findings suggest that it is the listener’s combined use of both observing and listening skills that allows the listener to identify discrepancies and incongruities between the speaker’s verbal and nonverbal behaviors. The discovery of this type of discrepancy is an issue that the helper and helpee will ultimately have to deal with in the later phases of counseling.

In terms of listening skills, common sense would tell us that, because we have spent so much of our time in listening situations, we should be very good at it. (Approximately 40 percent of a person’s daily verbal interaction is spent in listening.) Unfortunately, communication research suggests that immediately after listening to a short talk, a person remembers only one-half of what he or she has heard. This is not because the listener has not had time to listen. Most people are capable of comprehending speech at a rate three to four times faster than normal conversation. Thus the listener has plenty of time to think. The key to effective listening appears to be how the listener uses her or his extra “thinking time.”

In summary, the research evidence suggests that the prehelping skills of positioning, observing and listening appear to be both cumulative and causative skills. First of all, these prehelping skills are cumulative in that the helper can improve his or her observing skills through careful positioning; similarly, a helper can improve her or his listening skills by observing and positioning well. Second, these pre-helping skills are causative in terms of their effect on the helpee.

Preparing increases the chances of the helpee appearing for help. The helpee who appears for help becomes the subject of the helper’s constant positioning skills, which in turn facilitates the helpee’s expression of nonverbal behavior. The helpee, as he or she expresses himself or herself nonverbally, becomes the subject of the helper’s observing skills, which in turn facilitate the helpee’s verbal expressions. The verbal expressions of the helpee become the target of the helper’s listening skills. Finally, it is this combination of the helper’s preparing, positioning, observing and listening skills that facilitates the helpee’s expression of personally relevant material to which the helper must skillfully respond.

Most major theoretical orientations to counseling and psychotherapy have recognized the importance of the patient talking about what is troubling him or her. In particular, Freud (1924) popularized a “talking cure” for emotional problems, while Rogers, Gendlin, Kiesler, & Truax (1967) strongly stressed the necessity of helpee self-exploration. In addition to these theoretical emphases, a great deal of research has been amassed that indicates a significant positive relationship between the degree of helpee self-exploration and therapeutic outcome. That is, those helpees who talk in greater detail about their unique problems and situations are more apt to improve over the course of helping.

One of the reasons for the increasing number of studies on helpee self-exploration has been the development of reliable and observable rating scales by means of which the dimension of self-exploration can be analyzed. The most widely used scale of self-exploration, upon which countless numbers of research investigations have been carried out, can be found in Robert R. Carkhuff’s Helping and Human Relations, Volume 2 (1969 & 1984).

Effects of Helper Responding Skills on Helpee Exploration

Perhaps one of the most significant scientific discoveries in therapeutic research is that certain skills the helper uses directly influence the degree to which a helpee will explore personally relevant material (Carkhuff, 1969; Rogers et al., 1967; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). These helper skills, once referred to as the facilitative conditions of empathy, respect, and genuineness, are now operationalized in the helper skill of responding. A series of experimental studies found that a helper can deliberately increase and decrease the helpee’s depth of self-exploration by directly changing the level of the helper’s responding skills (Cannon & Pierce, 1968; Holder, Carkhuff, & Berenson, 1967; Piaget et al., 1967; Truax & Carkhuff, 1965). The research results show that when the helpers were most responsive, the helpees’ self-exploration was much more personally relevant; when these same helpers became less responsive, the helpees’ exploration became less personal. In addition, the effects of relatively unskilled helpers on helpee self-exploration were also studied. Investigators discovered that the helper who is unskilled in responding will, over time, decrease her or his helpees’ level of self-exploration.

This is not to say that the helpee does not have a role to play in how willing he or she is to explore personally relevant material. Some helpees are certainly more willing to explore themselves than are other helpees. However, the research supports the belief that, irrespective of the helpees’ own ability and willingness to explore, the responding skills of the helper can directly influence helpee self-exploration; and helpees who have helpers who are unskilled in responding will gradually introduce less and less personally relevant material into the helping interaction.

Although a helper can certainly do more than just use her or his responding skills, responsive skills in and of themselves, can, at times, have a differential effect on helpee outcome.

Several experimental studies have demonstrated that the outcome of a conditioning or a reinforcement program was found to be, in part, a function of the level of responding skills exhibited by the experimenter/helper (Mickelson & Stevic, 1971; Murphy & Rowe, 1977; Vitalo, 1970).

Undoubtedly the most significant and meaningful finding with respect to the relationship between responding skills and helping outcome has been made in the field of education. Over the past two decades, one finding has consistently emerged from educational research: a positive relationship exists between the teacher’s responding skills and various measures of student achievement and other educational outcomes (Aspy, 1973; Aspy & Roebuck, 1977; Carkhuff, 1971 a; Carkhuff & Berenson, 1976; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). Thus a teacher’s ability to respond to her or his students will affect how much those students learn. More recent studies have shown that a teacher’s responding skills are not only positively related to education outcome criteria but also to criteria that have primarily been the goals of guidance counselors and other mental health professionals—criteria like improved student self-concept and decreased student absenteeism.

In summary, the skilled helper, regardless of his or her theoretical orientation, has much to gain by using responding skills. First, the use of responding skills will directly influence the amount of personally relevant material the helpee will express to the helper. Second, helpers who are trying to get their helpees to learn certain skills or follow a certain program will improve the outcomes of their helping programs if they are able to respond skillfully to the helpees’ experiences.

Personalizing Skills

Research has shown that there are skills beyond responding that a helper can use to assist the helpee to develop personal insights into his or her unique situation (Carkhuff, 1969,1971 a; Carkhuff & Berenson, 1977; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). In other words, the skills of responding are usually necessary but rarely sufficient. It is typically not enough for the helper to see the world only through the helpee’s eyes. The helpee is often unable to develop the necessary insights by herself or himself; at these times, the helper must use interpretive skills to go beyond what the helpee can do on his or her own.

What is needed is a transitional stage between helpee exploration and helpee action. This stage is understanding. It is a stage in which the helpee comes to “personalize” or “individualize” his or her problems and goals. The helper’s task during the understanding phase is to formulate and communicate the helpee’s personalized problems and goals (Carkhuff & Berenson, 1977). This personalized understanding relates the helpee’s exploration to action programs that the helpee wants and needs. Personalizing helps the helpee to programmatically develop insights into his or her problems and goals before embarking upon an action course.

A rather ingenious study examined the relationship between a therapist’s theoretical orientation and the level of personalizing skills that he or she demonstrates in a counseling interview. The study divided the professional therapists (all M.D.’s and Ph.D.’s) into three major theoretical orientations—psychodynamic, behavioristic, and humanistic—based on the therapists’ own stated preferences. Each therapist tape recorded an actual interview with a pseudo-client. Ratings of the therapists’ personalizing skills evidenced no significant differences between therapists of any of the three theoretical orientations, even though theoretically one would expect their levels of personalizing skills to differ (Fischer, Pavenza, Kickertz, Hubbard, & Grayston, 1975).

These research studies, as well as the current plethora of counseling theories, have a fairly straightforward implication for the development of counselor personalizing skills. That is, it would certainly be premature to make interpretations based exclusively on any one theory of psychotherapy. It would appear that at the present state of our research and theoretical knowledge, it would be most effective to assume an eclectic theoretical stance. The “appropriateness” of any theory is a function of how well the theoretical perspective allows the helper to make personalized responses to the helpee—a personalized response to which the helpee can understand and agree—which in turn sets the stage for effective helpee action, which is the next phase of the helping process.

One series of studies was undertaken to assess whether counselors who were able to demonstrate their responsive and interpretive skills with a client were different in any other ways from helpers whose best responses demonstrated only attending, listening and/or responding skills (Anthony, 1971). To ensure that counselors in the study would be functioning at interpersonal skill levels greater than the average counselor, this study used counselors who had just received a 30-hour interpersonal skills training experience. Each counselor conducted a 30 to 40 minute interview with the same physically disabled client. Comparisons between counselors who were rated as functioning at relatively higher levels of interpersonal skills versus those counselors who were functioning at slightly lower levels indicated that the higher level counselors outperformed their relatively lower level functioning counterparts on four indices: (1) client’s depth of self-exploration; (2) counselor’s level of immediacy after confrontations by the client; (3) counselor’s use of confrontation; and (4) counselor’s score on a test reflecting the favorability of the counselor’s attitude toward physically disabled persons. The results of this study suggest that meaningful differences exist between those counselors who possess both responding and interpretive or personalizing skills and those who do not. Particularly significant is the fact that the high-functioning group of counselors had a greater effect on a client-process measure related to counseling outcome (client self-exploration).

Another series of experimental studies investigated one such instance when it is necessary for the helper to become additive in his or her understanding, that is, when the helpee becomes reluctant to engage in any further self-exploration (Alexik & Carkhuff, 1967; Carkhuff & Alexik, 1967). In these research studies the client, unknown to the therapists involved, was given a mental set to explore herself deeply during the first third of an interview, to talk only about irrelevant and impersonal details during the middle third, and to explore herself deeply again during the final third of the interview. The research data indicated that in the middle third of the session, when the client began to “run away” from the therapeutic encounter, the most responsive therapists began to become more interpretive, more immediate, and more confronting; overall, more personalized in their understanding of the helpee’s immediate problems.

The skill of confrontation is a therapeutic technique that can be one of the most potent (albeit one of the most abused) interpretive skills. Berenson and Mitchell (1974) have comprehensively researched and analyzed the unique contributions of the skill of confrontation. Their ground-breaking efforts in this area have led to many specific conclusions including the following: (a) that helpers who have a higher level of responsive skills confront in a different and more effective manner than helpers who possess low levels of responsive skills; (b) that there are different types of confrontation that can be used most effectively when applied in a certain sequence; and (c) that confrontation, in and of itself, is never a sufficient therapeutic skill.

A number of approaches to counseling and psychotherapy emphasize the understanding phase of helping. Best known, of course, are the psychoanalytic and neoanalytic positions (Adler, 1927; Brill, 1938; Freud, 1924, 1933; Fromm, 1947; Homey, 1945; Jones, 1953; Jung, 1939; Mullahy, 1948; Rank, 1929; Sullivan, 1948).

Most modern psychoanalysts and psychiatrists, whose predominant technique is psychoanalysis, recognize that although psychoanalytic theory may have contributed to the beginnings of an understanding of human thoughts and feelings, many of the techniques and assumptions of classical analysis are no longer adequate (Loran, 1972; Freund, 1972; Conn, 1973; Friedman, 1975; McLaughlin, 1978; Older, 1977). With their basic assumption concerning the evil nature of mankind, the classical psychoanalytic position emphasized analyzing away client destructiveness. The final irony is that “after peeling back the trappings and exposing the undergarments of an ugly world, Freud found no alternatives” (Carkhuff & Berenson, 1967, p. 107). The psychoanalytic positions had no real constructive alternatives to offer.

Some of the existential approaches to therapy attempted to fill this void by offering their cosmologies as alternatives to the psychoanalysts’ assumptions of pathology (Binswanger, 1956; Boss, 1963; Heidegger, 1962; May, 1961). Unfortunately, in the process of maximizing the emphasis upon honest encounter in the exchange of cosmologies, the existential approaches minimized the role definition of the helper. Thus, paradoxically, they failed to define the skills that are part and parcel of any effective cosmology (Carkhuff & Berenson, 1977).

There are a number of helping orientations that offer constructs or “handles” that may be useful in expanding the helpees’ insights into what they are doing to contribute to their problems. The effective helper may draw from a variety of systems when helping to personalize the understanding of the helpee. The limit of simply exchanging one cosmology for another, however, is that the helpers are asking the helpees to fit their models of functioning rather than to develop the models to fit the helpees. A helper must be open to new orientations yet always oriented to observable and measurable effectiveness for each individual helpee. Personalizing skills offer helpers an opportunity to work with helpees to overcome personalized problems and achieve personalized goals in their lives.

Initiating Skills

One of the reasons why the continual challenges to the efficacy of counseling and psychotherapy have not been completely answered is that therapists have typically not defined their goals in observable terms. For example, helpers often describe helpees as needing to become more motivated, adjusted, self-actualized, self-accepting, congruent, insightful and so on. These goals certainly do not describe an observable activity; as a result, their achievement would be difficult to document and verify. The critics of psychotherapy have not claimed that psychotherapy is ineffective; rather, they have pointed out that the evidence that does exist has failed to indicate that psychotherapy IS EFFECTIVE (Eysenck, 1972). In other words, the burden of proof is on the provider of the service; and unless therapeutic goals are defined as meaningful, observable and measurable, then therapeutic effectiveness is difficult to document.

Defining Goals Can Get Results

The ability to define or operationalize goals, then, is the key to the effective action-steps that the helpee must take (Carkhuff, 1969, 1984). A goal is defined in terms of the operations required to achieve it. A goal is, therefore, observable, measurable and achievable (Carkhuff, 1974, 1985 a).

Perhaps one of the most intriguing findings with respect to the skill of goal definition is that simply requiring the therapist to set observable goals seems to improve therapeutic outcome in and of itself. In an experimental study of the benefits of goal definition, Smith (1976) had one group of adolescent helpees counseled by professional therapists in their own style with one notable exception: the therapists had been instructed in how to define observable goals for their helpees. Another group of therapists counseled their helpees without receiving prior training in defining observable helpee goals. At the end of eight counseling sessions, the group of helpees aided by counselors who had defined observable goals showed significantly greater improvement on a variety of counseling outcome indices. In an entirely different study, client satisfaction and subsequent prediction of recidivism was found to be related to client goal-attainment (Wilier & Miller, 1978).

Walker (1972), in studying an agency designed to rehabilitate the hardcore unemployed, found that, when feedback to the helpers about how well their helpees were achieving observable rehabilitation goals was experimentally withdrawn, the number of helpees rehabilitated decreased; likewise, when the helpers were once again provided feedback as to how well their helpees were achieving their goals, the helping outcome improved once again. In other words, the setting of observable helpee goals combined with feedback to the helpers in terms of how well the helpees are achieving these goals can, in and of itself, improve an agency’s helping outcome. Other researchers have reported similar positive effects of goal-setting training in improving general job performance (Latham & Rinne, 1974; Bucker, 1978; Erez, 1977; Holroyd & Goldenberg, 1978; Flowers & Goldman, 1976).

In summary, flowing from the helpee’s extensive exploration of where he or she is, the helping process converges in the helpee’s understanding of the goals for where he or she wants or needs to be. The ability to achieve these goals is a function of the ability to define or operationalize each goal. Given the time and the resources, any goal that can be operationally defined can be achieved.

Teaching as Treatment

In 1971, Carkhuff suggested that training clients directly in the skills that they need to function in society would be a potent treatment method. In other words, once the helper established an effective therapeutic relationship, identified with the helpee what specific goals needed to be attained, and developed the necessary program steps, the helper would then involve the helpee in skills-training programs designed to achieve these goals. As a helper moves from training individual clients to teaching groups of clients, the helper-teacher must be much more knowledgeable about those teaching skills needed by the helper to facilitate the skill-learning process of groups of clients (Carkhuff & Berenson, 1976).

Interestingly enough, some of the most ingenious skills-training programs have been developed to systematicallly teach clients the same relationship skills that the effective helper uses in the helping process. That is, skills-training programs have been developed to teach clients how to respond to others and themselves in a skillful manner so that these clients may function more effectively in interpersonal situations.

Some of the earliest skills-training programs trained psychiatric inpatients in responding skills (Pierce & Drasgow, 1969; Vitalo, 1971). Both of these studies found that psychiatric patients could be trained to function at higher levels of interpersonal skills and that these trained patients achieved a higher level of interpersonal functioning than a variety of control and other treatment conditions. Similar results have been found in training parents (Carkhuff & Bierman, 1970; Reed, Roberts, & Forehand, 1977) and mixed racial groups (Carkhuff & Banks, 1970).

No doubt one of the most comprehensive studies of the effects of a training-as-treatment approach has been the changeover of an entire institution for delinquent boys from a custodial to a skills-training orientation (Carkhuff, 1974). Correctional personnel with no credentials in mental health were trained in interpersonal, problem-solving and program-development skills. Using the skills, the correctional personnel helped develop and deliver more than eighty skills-training programs in a variety of physical, emotional and intellectual areas of functioning.

The results achieved by these correctional personnel were quite dramatic, indicating that they were able to bring about a kind of inmate change of which credentialed mental health professionals would be justifiably proud. A summary of the various outcome criteria used indicates that the delinquents’ physical functioning increased 50 percent, their emotional functioning 100 percent, and their intellectual functioning 15 percent. The physical functioning measure assessed seven categories of physical fitness as developed by the American Association for Health, Physical Education and Recreation; the emotional functioning measure involved a rating of the juveniles’ human relations skills; intellectual functioning was measured by the California Achievement Test. In addition to the gains in physical, emotional and intellectual functioning, during a one-year period, “Elopement” status decreased 56 percent, recidivism rates decreased 34 percent, and crime in the community surrounding the institution decreased 34 percent.

Following this study an extensive number of programs utilizing teaching as a preferred mode of treatment with problem youth were reported. For example, delinquent youth with low levels of living, learning and working skills were trained in those skills. The results yielded recidivism rates of approximately 10 percent after one year and 20 percent after two years, against base rates for the control groups of 50 percent and 70 percent, respectively (Collingwood, Douds, Williams, & Wilson, 1978).

In addition, youthful minority-group dropout learners were taught “how-to-learn reading and mathematics skills.” The results indicated that the students were able to gain one year or more in intellectual achievement in twenty-six two-hour sessions (Berenson, Berenson, Berenson, Carkhuff, Griffin, & Ransom, 1978). Clearly, teaching is a preferred mode of treatment in both preventative and rehabilitative modalities.

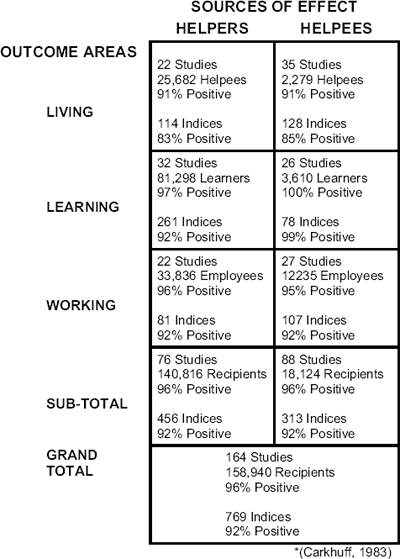

The research of helping skills demonstrations over two decades is summarized in Table 1 (Carkhuff, 1983). As can be seen in Table 1, 164 studies were reported with 158,940 recipients involved. The studies are divided as to the sources of their effect upon helpees—the effect of training helpers or the effects of training helpees directly. In turn, the effects are divided by areas of functioning; living, learning and working areas. The studies of the effects of helpers upon helpees are 96 percent positive, while the indices are 92 percent positive. This means that various helpers (parents, counselors, teachers, employers) have constructive effects upon their helpees (children, counselees, students, employees) when trained in interpersonally based helping skills. The studies of the direct effects of training the helpees are also 96 percent positive while the indices are 92 percent positive. This means that trained helpees (children, counselees, students, employees) demonstrate constructive change or gain when trained in interpersonally based self-helping skills.

Overall, the studies show that the effects of interpersonal skills training upon helpers and the direct training upon helpees are 96 percent positive while the indices are 92 percent positive. This means that our chances of achieving any reasonable living, learning or working outcome are about 96 percent when either helpers or helpees are trained in interpersonally based helping skills. Conversely, the chances of achieving any human goal without trained helpers or helpees are random.

Together, the results of these studies constitute an answer to the challenges to the efficacy of the helping professions (Anthony, 1979; Eysenck, 1960, 1965; Levitt, 1963; Lewis, 1965).

Table 1: A Summary of Interpersonal Skills Training Studies and Results Across Multiple Indices of Helpee Living, Learning and Working Outcomes*

In early research, helpee outcomes emphasized the emotional changes or gains of the helpees. Since the helping methods were insight-oriented, the process emphasized helpee exploration, and the outcome assessments measured the changes in the helpee’s level of emotional insights (Rogers et al., 1967; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). Clearly, these emotional outcomes were restrictive because they were assessing only one dimension of the helpee’s functioning.

These outcomes were later defined more broadly to incorporate all dimensions of human development to which the helping process is dedicated. The emotional dimension was extended to incorporate the interpersonal functioning of the helpees (Carkhuff, 1969, 1971 a, 1983, 1984). The dimension of physical functioning was added to measure relevant data on the helpees’ fitness and energy levels (Collingwood, 1972). The intellectual dimension was added to measure the helpees’ intellectual achievement and capabilities (Aspy & Roebuck, 1972,1977).

In summary, helping effectiveness is a function of the helper’s skills to facilitate the helping process to accomplish helping outcomes. Helping outcomes include the physical, emotional and intellectual dimensions of human development. The helping process, by which outcomes are accomplished, emphasizes the helpee’s explorating, understanding and acting. The helping skills, by which the process is facilitated, include attending, responding, personalizing and initiating skills.

The Training Applications

It was a natural step to train helpers in helping skills and study the effects on helping outcomes. It was also only natural that the first training applications take place with credentialed counselors and therapists. Next came the training of lay and indigenous helper populations, followed by the direct training of helpee populations to service themselves.

Credentialed Helpers

The first series of training applications demonstrated that professional helpers could be trained to function at levels commensurate with “outstanding” practitioners (Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). In a later series, it was established that credentialed professionals could, in the brief time of 100 hours or less, learn to function above minimally effective and self-sustaining levels of interpersonal skills, levels beyond those offered by most “outstanding” practitioners (Carkhuff, 1969, 1983 a). Perhaps most importantly, trained counselors were able to involve their counselees in the helping process at levels that led to constructive change or gain. In one demonstration study in guidance, against a very low base success rate of 13 to 25 percent, the trained counselors were able to demonstrate success rates between 74 and 91 percent (Carkhuff & Berenson, 1976).

A series of training applications in teaching soon followed. Hefele (1971) found student achievement to be a function of systematic training of teachers in helping skills. Berenson (1971) found the experimentally-trained teachers were rated significantly higher in interpersonal skills and competency in the classroom than were other teachers who received a variety of control conditions. Aspy and Roebuck (1977), building upon their earlier work, have continued to employ a variety of teacher training strategies demonstrating the positive effects of helping skills upon student physical, emotional and intellectual functioning.

It is clear that a dimension such as interpersonal functioning is not the exclusive province of credentialed professionals. Lay personnel can learn as well as professionals to be empathic in their relations with helpee populations. With this growing recognition, a number of training applications using lay personnel were conducted. The majority of these programs dealt with staff personnel.

Staff personnel, such as nurses and hospital attendants, police and prison guards, dormitory counselors and community volunteers, were trained and their effects in treatment studied. The effects were very positive for both the staff and helpee populations for, after all, the line staff and helpee populations were those who lived most intimately with each other. In general, the lay helpers were able to elicit significant changes in work behaviors, discharge rates, recidivism rates and a variety of other areas including self-reports, significant-other-reports and expert-reports (Carkhuff, 1969, 1971 a, 1983; Carkhuff & Berenson, 1976).

Interpersonal-skills based training of managers and supervisors in business and industry has resulted in significant increases in worker productivity and cost avoidance. In training programs involving more than 2,000 managers and impacting nearly 25,000 employees, R.O.l.s (Return on Investment) ranged between 10:1 for one year to 30:1 for three years (Carkhuff, 1983,1984).

Indigenous Personnel

The difference between functional professional staff and indigenous functional professionals is the difference between the attendant and the patient, the police officer and the delinquent, the guard and the inmate, and the teacher and the student. That is to say, indigenous personnel are part of the community being serviced. It is a natural extension of the lay helper training principle to train helpee recipients as well as staff.

Here the research indicates that, with systematic selection and training, indigenous functional professionals can work effectively with the populations from which they are drawn. For example, human relations specialists drawn from recipient ranks have facilitated school and work adjustments for troubled populations. New careers teachers, themselves drawn from the ranks of the unemployed, have systematically helped others to learn the skills they needed in order to get and hold meaningful jobs (Carkhuff, 1971 a, 1983).

Helpee Populations

The logical culmination of helper training is to train helpee populations directly in the kinds of skills that they need to service themselves. Thus, parents of emotionally disturbed children were systematically trained in the skills that they needed to function effectively with themselves and their children (Carkhuff & Bierman, 1970). In another series of studies, patients were trained to offer each other rewarding human relationships. The results were significantly more positive than all other forms of treatment, including individual or group therapy, drug treatment or “total push” treatment (Pierce & Drasgow, 1969). Training was, indeed, the preferred mode of treatment!

The concept of training as treatment led directly to the development of programs to train entire communities to create a therapeutic milieu. This has been accomplished most effectively in institutional-type settings where staff and residents are trained in the kinds of skills necessary to work effectively with each other. Thus both institutional and community-based criminal justice settings have yielded data indicating reduced recidivism and increased employability (Bierman, et al., 1976; Carkhuff, 1974; Collingwood et al., 1978; Montgomery & Brown, 1980).

In summary, both lay staff and indigenous personnel may be selected and trained as functional professional helpers. In these roles, they can effect any human development that professionals can—and more! Further, teaching the helpee populations the kinds of skills that they need to service themselves is a direct extension of the helper principle. When we train people in the skills that they need to function effectively in their worlds, we increase the probability that they will, in fact, begin to live, learn and work in increasingly constructive ways.

Conclusions

In summary, training in interpersonal skills-based helping programs significantly increases the chances of our being effective in improving indices of helpee living, learning or working. Simply stated, trained helpers effectively elicit and use the input and feedback from the helpees concerning their helping effectiveness. Similarly, trained helpees learn to relate up, down and sideways in developing their own goals and programs.

We have found that all helping and human relationships may be “for better or for worse.” The effects depend upon the helper’s level of skills in facilitating the helpee’s movement through the helping process toward constructive helping outcomes. These helping skills constitute the core of all helping experiences.

The helping skills may be used in all one-to-one and one-to-group relationships. They are used in conjunction with the helper’s specialty skills. They may be used in conjunction with any of a number of potential preferred modes of treatment, drawn from a variety of helping orientations, to meet the helpee’s needs. Finally, the same skills may be taught directly to the helpees in order to help them help themselves: teaching clients skills is the preferred mode of treatment for most helpee populations.

In conclusion, the helping skills will enable us to have helpful rather than harmful effects upon the people with whom we relate. We can learn to become effective helpers with success rates ranging upwards from two-thirds to over 90 percent, against a base success rate of around 20 percent. Most importantly, we can use these skills to help ourselves and others to become healthy human beings and to form healthy human relationships.

The Future of Helping

The future of helping lies in systematic approaches to human capital development. Operating proactively, we may develop guidance and preventative mental health training programs emphasizing youth development. Operating reactively, we may develop counseling, therapeutic and rehabilitation training programs which programmatically move from the helpees’ frames of reference to observable and measurable physical, emotional and intellectual development. The key is helping skills—helping skills that facilitate the helpees’ movement through exploring, understanding and acting. These helping skills emphasize interpersonal processing skills.

The future of helping also lies in the “morphing” of HRD models into human capital development of HCD models (Carkhuff, 2000). The principle difference between the two is the HCD emphasis upon intellectual processing: individual, interpersonal, interdependent. HCD emphasizes those resources that make us most important or capital in the 21st century.

Moreover, the future of helping is interdependently related to the future of science. When helping becomes a synergistic processing partner with the new science of possibilities (Carkhuff and Berenson, 2000 a, b) and its applications (Carkhuff and Berenson, 2000 a, b), then it will introduce both helpers and helpees to the realm of infinite possibilities: helpers will become “scientist–artists” who process interdependently with their helpee populations; helpees will become invaluable resources who are introduced to infinite possibilities.