CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Identify the factors that create the risks related to retirement

- Identify the two financial risks that arise in connection with the retirement risk

- Identify the three broad steps in the retirement planning process

- Identify the three lines of defense that constitute a well-designed retirement plan

- Identify and describe the two approaches that may be used to estimate retirement needs

- Explain the strategies that may be followed in managing the distribution of a retirement accumulation

In this chapter, we turn to the other side of the life contingency risk, the possibility of outliving one's income, which is the retirement risk. As we noted in Chapter 10, the retirement risk is the complement of the risk of premature death. If the individual dies prematurely, he or she will have no need for funds accumulating for retirement. If the individual lives until retirement, provision made for premature death will be unused, but there is a need for retirement funds. Because either outcome could occur, the individual must make provision for both contingencies.

![]()

AN OVERVIEW OF THE RETIREMENT RISK

![]()

For the average college student, who has yet to begin a career, the time at which that career is likely to come to an end seems irrelevant. It is difficult to imagine the time at which the working years will come to an end. It is even harder to imagine that at the time they end, there might be too few assets to live comfortably for the remainder of one's lifetime. But this is the essence of the retirement risk.

![]()

Causes of the Retirement Risk

The retirement risk arises from uncertainty concerning the time of death. It is influenced by physiological and cultural hazards. As a society, our population tends to live longer after retirement than any previous generation. In 1935, a woman who reached age 65 in good health could plan on living another 13 years; for a man the life expectancy was about 12 years. By 2013, a woman who reached age 65 in good health had a life expectancy of 21 years, and a man had an expectancy of 19 years. For the current college-age population, life expectancies are even longer. Many of today's college students will live 25 to 30 percent of their life span after they retire.

![]()

Two Risks Associated with Retirement

Although they are closely related, two distinguishable risks are associated with retirement. The first is the possibility that the individual may have accumulated insufficient assets by the time he or she reaches retirement age. The second is the possibility that the individual may outlive the assets that he or she has accumulated. Even if the individual has accumulated sufficient assets to provide an adequate standard of living after retirement, uncertainty concerning the life expectancy raises a problem regarding the portion of the accumulation that should be consumed each year so the accumulation will last for the individual's entire lifetime. This second problem is the easier of the two to address. The annuity principle, in which a principal sum is liquidated based on life expectancies, can be used to convert an accumulation into an income the individual cannot outlive. In Chapter 18, we discussed the specifics of different types of annuities. Annuities are essential tools in managing the retirement risk and they provide a convenient solution to the second problem associated with retirement, the possibility of outliving the retirement accumulation.

![]()

Retirement Risk Alternatives

Some people attempt to avoid the risk of outliving their income by not retiring. Although societal pressures and corporate policies sometimes mitigate against this strategy, many continue working beyond the normal retirement age by preference or out of necessity. People who elect not to retire do not, however, totally avoid the risk they may outlive their income. Even if the individual decides to continue working beyond the “normal” retirement age, the possibility of becoming disabled increases significantly beyond age 65. Since disability income policies do not provide full coverage beyond age 65, the individual may find himself or herself in an involuntary retirement forced by disability. Although continued employment at retirement age does not avoid the risk of outliving one's income, it reduces the risk. With increasing longevity, delayed or phased retirement (in which the individual works part time) is becoming more common.

Transfer is also used as a technique for dealing with the retirement risk. A part of the retirement risk is transferred to that workforce portion that will be employed when the individual retires. Under the Social Security system, taxes paid by employed workers provide the funding for Social Security beneficiaries. In addition, annuities can be used to transfer the risk of outliving an accumulated sum to an insurer. Finally, some individuals transfer the retirement risk to their children or to society, by not preparing for retirement.

Although the provision for one's retirement may combine the techniques of avoidance, reduction, and transfer, the primary technique for dealing with the retirement risk is retention. As in the case of other retention strategies, this requires the accumulation or identification of the funds that will be required to meet the loss when it occurs.

![]()

An Overview of the Retirement Planning Process

Retirement planning involves three steps that more or less parallel those that we have considered in planning life insurance needs.

- The first step is to estimate the future income need. This requires predicting the income needs that will exist after retirement and identifying the available sources used to meet these needs.

- The second is to determine how the funds required to meet the needs defined in step one will be accumulated. This involves designing and implementing a plan to accumulate assets sufficient to fund the difference between the resources needed and the resources available to provide the required retirement income.

- The final step is to plan the manner in which the accumulation will be consumed. This requires consideration of the period over which the retirement accumulation will be consumed and the provision that should be made for a spouse.

Sources of Retirement Funding Four broad sources of funding exist for the retirement need: Social Security, qualified pensions and profit-sharing plans, private savings, and supplemental earnings from part-time employment. These are referred to as the four pillars of retirement.

Pillar 1: Social Security For most people, the first source of retirement income will be Social Security. The adequacy of Social Security retirement benefits depends mostly on the standard of living the retiree wishes to maintain. Because Social Security benefits are computed in a manner favoring those in low-income classes, it provides about 60 percent of the retirement needs for minimum-wage earners but less than 30 percent of the retirement needs for those who earned the maximum Social Security taxable wage base. In addition to the smaller percentage of preretirement income that Social Security replaces for middle-income and upper-income categories, some question whether to project present Social Security benefit levels into the future is reasonable. Given the financial difficulties facing the system, we will likely see additional measures aimed at correcting the system's problems. Judging from the measures that have been adopted in the past, the changes could reduce the level of benefits for some retirees. As we saw in Chapter 11, the Social Security benefits of individuals (and couples) with significant income from other sources are subject to the federal income tax. In addition, the retirement age at which full benefits will be payable is scheduled to increase gradually from its current level to age 67. Although the situation does not seem sufficiently precarious to warrant ignoring the Social Security benefits available to the individual, vigilance in monitoring the retirement program is suggested.

Even barring changes in the Social Security benefit structure, Social Security benefits are rarely adequate to continue the worker's preretirement standard of living. Income from Social Security must be supplemented by other income sources. One possibility is for the worker to accept employment after the Social Security benefit has begun. Although this may be the only alternative, Social Security regulations relating to earnings of beneficiaries impose an enormous tax on postretirement earnings. As noted in Chapter 11, income earned by a Social Security beneficiary may reduce the Social Security benefit. Although beneficiaries over the full retirement age have no limit on their earnings, beneficiaries below that age can lose Social Security benefits if their earnings exceed specified levels. This means that a retired worker who must work to maintain a desired standard of living may suffer a reduction in benefit that, combined with the Federal Insurance Contribution Act (FICA) and income tax on the earnings, will diminish the employment benefit.1

Pillar 2: Qualified Pensions and Profit-Sharing Plans For some people, an employer-sponored pension or profit-sharing plan will be available to supplement the benefits provided by Social Security. Although qualified retirement plans have traditionally been considered another keystone in the individual's retirement planning, only about 50 percent of the workforce have any pension plan. In addition, the trend has been away from the defined benefit plan to defined contribution plans, which, as we have seen, place the investment risk associated with the plan on the employee. There has also been a shift to the increasingly popular Section 401(k) plans, in which employees defer income in tax-sheltered contributions. In some cases, the employer matches the employee's contribution to these plans, in other cases not. When the employer contributes to the plan, the individual's burden in constructing the third part of the program is less. When the employer does not contribute, the employee should still take advantage of the opportunity to shelter a part of his or her income.

Pillar 3: Personal Savings The benefits provided by Social Security and an employer-sponsored pension will rarely provide a retirement income adequate for retirement needs. Depending on whether the individual is covered by a corporate pension plan, any where from 30 percent to 70 percent of the retirement income will have to come from savings generated during the individual's income-earning years.

TABLE 19.1 Accumulation of $1,000 Annual Investment

An obvious question that arises in connection with the funds accumulated for retirement relates to the form in which these funds should be held. Various options include life insurance and annuities, government bonds, corporate bonds, stocks, mutual funds, limited partnerships, and real estate. Financial planners have identified a number of criteria to consider in selecting the long-term investments used in accumulating the personal savings component of one's retirement income. These include the rate of return, vulnerability to inflation, tax treatment, and safety of principal. Appropriate consideration should be given to each of these factors in selecting investments for the retirement portfolio. Annuities (and life insurance), because of their favorable tax treatment, deserve consideration for inclusion in the retirement accumulation.

There is an obvious relationship between the tax treatment of investments and their rate of return. Differences in tax treatment produce different rates of return over the accumulation period that, in turn, influence the amount a given dollar level of investment will produce. The different rates of return and their associated accumulations indicated in Table 19.1 show the dramatic effect of differences in rates of return on a growing fund. If a part of the investment income cannot be reinvested because it must pay taxes, the realized rate of return will be lower. Investments on which the investment income accumulates tax-free, or on which the taxation of the investment return is deferred, will accumulate more rapidly and provide a greater terminal value than when the increments are subject to current taxation.

Because of the differential rates of growth associated with different rates of return, the investment accumulation should make maximum use of tax-deferred vehicles. When permitted, voluntary contributions to an employer-sponsored plan will provide the desired tax deferral. Similarly, investment in an IRA, even on a nondeductible basis, will shelter the investment income from current taxation, thereby increasing the accumulation.

Careful thought should be given to the relative attractiveness of using deductible tax-deferred savings (such as a traditional IRA or traditional 401(k) contributions) versus Roth accounts. As described in Chapter 18, with a Roth IRA, the taxpayer makes nondeductible contributions, which accumulate tax-free. No taxes are owed on distribution. Beginning in 2006, employer-sponsored 401(k) and 403(b) plans were permitted to accept Roth contributions from employees. Because the accumulation is not taxed when distributed, Roth accounts offer the ability to hedge against future tax increases.2

Current marginal federal income tax rates are at historically low levels.3 The maximum marginal tax rate is currently 39.6 percent; in the 1960s, the top rate was 90 percent. If tax rates increase, contributions to a traditional plan will escape current taxation only to be taxed at higher levels in later years. At some point, the increased taxes can offset the advantages of the tax deferral. To contrast, with a Roth account, the participant elects to pay taxes on current income in return for eliminating the potentially higher taxes at retirement. Thus, these plans are attractive to individuals who expect to be in a higher tax bracket when they retire.

Finally, annuities, under which investment earnings accumulate on a tax-deferred basis, represent an attractive alternative. Unlike nondeductible contributions to an IRA, which are limited, there is no maximum on the amount that may be paid into an annuity. Given the wide range of options available in self-directed annuities, a portfolio of any dimension can be constructed using a deferred installment annuity. Because the tax on the investment income from the instruments included in the self-directed portfolio is deferred, the tax treatment of these instruments becomes inconsequential. There is no need to limit investments to those that receive favorable tax treatment since all investments in the annuity portfolio produce tax-deferred income.

Pillar 4: Earnings from Employment Traditionally, retirement planners referred to the “three legs” of the retirement stool, including Social Security, employer pension plans, and personal savings. Today, however, part-time employment during retirement years is recognized as an important resource, and the term “four pillars” has replaced “three-legged stool.” Individuals may seek part-time employment because the combination of Social Security, employer pensions, and personal savings is inadequate to support their desired lifestyle. Alternatively, they may simply enjoy the work experience. Either way, income from part-time employment can be an additional resource for some individuals. With increasing longevity, Social Security's financial challenges, and the decline in defined benefit pension plans, governments are also recognizing the value of encouraging continued employment past normal retirement age.4

![]()

Countering the Urgency Deficit

It has been suggested that an ambiguity in the terms important and urgent sometimes results in a distorted sense of priorities; importance and urgency do not always go together. Often, unimportant things get done because there is a sense of urgency, while important things are sometimes postponed to be done “later.” Retirement planning is a good example. Although most people would probably agree on the importance of retirement planning, the sense of urgency does not arise until the individual approaches retirement. Because there are many years until retirement when age 25 or 30 or 35, it is easy to delay designing and implementing a retirement program. The importance of timing rests in the effect of compound interest on regular contributions to an accumulating fund. The sooner one accumulates funds for retirement and the greater the amount one sets aside, the greater will be the accumulation when the individual retires. Consider again the accumulations at different rates of return indicated in Table 19.1, which indicates the impact that time and the rate of return can have on the accumulating fund. The longer the time before retirement one begins to make regular periodic contributions toward a retirement fund, the greater will be the accumulation. Except in cases where provision for retirement has been assured by a generous employer-sponsored plan, the individual is responsible for planning and executing that plan. The sooner one begins, the greater the likelihood of achieving the retirement goals that have been set.

![]()

CONSTRUCTING A RETIREMENT PLAN

![]()

As previously noted, retirement planning involves three basic steps:

- Estimating retirement needs

- Planning the retirement accumulation

- Planning the retirement distribution

The three steps are interrelated, and decisions in one step can influence choices in the other two. Estimating retirement needs involves choices that define the parameters for decisions in the second and third steps, but the financial realities encountered in steps two and three may require revisiting the decisions made in step one. We will begin our discussion with an examination of some issues that must be addressed in the first step of the process: estimating the retirement needs.5

![]()

Estimating Retirement Needs

The purpose of estimating retirement needs is to provide a goal or objective for the second step in the process, which is to plan the manner in which funds for retirement will be accumulated. Defining the retirement fund size to be accumulated involves two estimations: the total retirement income needed and the part of that need that will not be met from existing resources.

Estimating the Aggregate Need With respect to the total retirement income needed, one must determine the amount of monthly income that will allow the individual and his or her spouse to live after retirement. The amount required for a comfortable retirement will depend on the lifestyle to which the individual or couple aspires after retirement and on the inflation rate.

Future income needs may be estimated in one of two ways. The first is to construct a budget for postretirement living, estimating the costs that will need to be met for housing, food, medical expenses, and so on. The second approach, which we will follow, is to set the retirement income need at some percentage of the preretirement income. This second approach assumes that changes in the cost of living will be reflected by changes in the individual's income, and that postretirement income needs can be estimated from the individual's preretirement income. Because preretirement income will be influenced by inflation and other changes in income as the individual progresses through a career, the initial calculation is to project present income to retirement age. Consider, for example, a 25-year-old person with a present annual income of $36,000, who plans to retire at age 65. Projecting present income at a modest annual increase of 3 percent, the present income will increase to slightly more than $114,000 by the time he or she reaches age 65. Assuming current tax rates, after-tax income will be about $90,000.

Once present income has been projected to a retirement-age income level, the income need at the beginning of retirement is set as a percentage or fraction of the preretirement income. The fraction of preretirement income established as the retirement income need will depend on personal considerations, the first of which is the lifestyle to which the individual aspires during retirement. Although it is traditional to assume that postretirement income needs will be less than the income need during the working years, some persons might need more. This is particularly true in the case of persons who plan to travel and engage in various recreational activities during retirement. For the purpose of illustration, we will follow convention and assume the retirement income need will be less than the income need during the working years. A reasonable fraction, for the purposes of our illustrations, is 75 percent of the preretirement income level. Using the projected after-tax income of $90,000 suggested, this indicates an initial retirement income need of $67,500.

Retirement needs may be expected to increase after retirement due to inflation. Even at a modest inflation rate of 3 percent, prices will approximately double over a 25-year period and the purchasing power of a fixed annual income will fall by half. This means that in projecting retirement needs an allowance should be made for inflation that will occur before and after retirement. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) indicates the historical inflation rate over the past 30 years has been about 5.6 percent annually. The inflation rate over the next 30 to 40 years may fluctuate and choosing an assumed rate is a judgment call. Any inflation rate selected is subject to error, but the greater error is in ignoring inflation, which in effect sets it to zero.

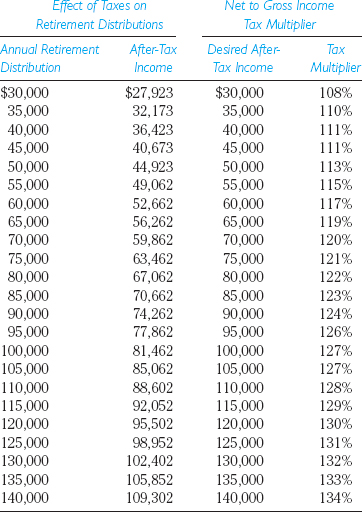

In addition to the allowance for inflation, a second adjustment is to recognize the effect of taxes on postretirement income. Because retirement distributions will be partly taxable, the retirement plan should be constructed to produce after-tax income in the amount required for postretirement needs. If the postretirement need is for say, $60,000 annually, the $60,000 should be converted into a pretax income. If the income will come from an accumulation composed of untaxed contributions (as in the case of a qualified plan), the entire distribution could be subject to tax. In other instances, only the investment earnings on the accumulation will be taxable. Although tax rates and other features of the tax code are subject to change, a reasonable approximation of the pretax income that will be required to produce a given amount of after-tax income can be estimated using tax multipliers. Assuming a retired couple filing a joint return, with current tax rates, standard deduction, and exemptions, the after-tax income for various taxable distributions is indicated in the first two columns of Table 19.2.

More useful information, from a planning perspective, is contained in the table's third and fourth columns. The final column indicates the multiplier that may be used to convert a given level of after-tax income need into a before-tax retirement distribution. As a consequence of the progressive tax rate, the higher the income level needed, the greater the difference between the amount needed and the pretax retirement distribution.

TABLE 19.2 Taxes and Retirement Distributions

Inventory of Available Resources Once the aggregate retirement need has been defined, the next step is to inventory the resources available to meet this need. For most people, the first source of retirement income will be Social Security. Many will supplement Social Security with the second layer of protection, a pension provided by the employer. If the individual is covered by a corporate pension or profit-sharing plan, the expected benefits from this source should be factored into the equation to determine the part of the postretirement need that will be met by Social Security and the pension.

This phase of the process is fraught with uncertainty. Any attempt to estimate the level of future Social Security benefits is subject to inaccuracy if for no other reason than the uncertainty about the future of the system itself. Despite the dire prophecies about the bankruptcy of the Social Security system, politicians will probably never scrap the system. At the same time, the changes that will probably be required to save the system will most likely have their greatest effect on the benefits of persons in middle-income and upper-income brackets. If one assumes a solution to the system's problems will be found and that solution will not alter the system's basic features, Social Security benefits can be projected at the same inflation rate as the projected increases in income. It is reasonable, however, to assume Social Security benefits will be fully taxable.

The projected income at retirement from the pension or other qualified retirement plan will depend on the nature of the plan and the extent to which benefits are guaranteed. In the case of a defined benefit plan, projecting retirement benefits based on projected income is reasonable. An adjustment should be made to reflect the nature of the plan (i.e., career average or final average salary). With a defined contribution plan, assumptions will be required concerning the rate of future contributions and investment earnings. In making these assumptions, the prudent course is to estimate a retirement benefits level based on conservative assumptions. Conservative assumptions are also recommended when projecting earnings during a phased retirement since poor health status or an economic downturn could interfere with these plans.

Summarizing the Unmet Need The preceding calculations indicate a monthly income flow needed after retirement. The next step is to convert this projected flow into a capital amount. The traditional technique for this is discounting. Ideally, the capital amount should reflect the influence of life expectancy and inflation. The problem is that while there are tools that reflect the influence of one or the other, no simple technique considers both.

Life-contingency risk is the uncertainty of death and the period for which the needs should be projected. This risk is easily addressed by using the purchase price for a life annuity at age 65 (or other retirement age). The cost of a life annuity at age 65 can be used to convert the monthly income required from private savings into a principal amount. For a male at age 65, the cost of a $10 monthly benefit is about $1100. For a female, it is about $1350. The cost of an annuity that will provide the required monthly amount is computed by dividing the monthly requirement by $10 to determine the number of $10-per-month units that must be purchased. If the monthly need is, say, $3000, the purchase price of an annuity that will provide $3000 per month to a 65-year-old female is $405,000:

![]()

The problem with this calculation is it indicates the amount required to provide a fixed, unchanging, income of $3000 a month, rather than an income that increases with inflation.

To consider the effect of inflation, one must project the initial need at some assumed rate of inflation and discount the projection to determine its present value. The problem with this method summarizing retirement needs is in determining the period for which the projection should be made. It is possible to compute a principal sum that allows increasing withdrawals for any period selected. In selecting any period, the planner makes an assumption about the retiree's longevity. This means the computation will be valid only for that particular longevity. One approach is to compute the inflation-adjusted income need for a period at least equal to the person's life expectancy, and then deal with the life contingency problem separately through the purchase of a life annuity.6

Illustrated Summary To illustrate the manner in which the factors discussed may be considered in estimating retirement income needs, consider the following example. The subject is 25 years old and currently earns $36,000 per year. Projecting the $36,000 at an assumed inflation rate of, say, 3 percent, the subject's salary will reach $114,013 at age 65 with after-tax income of $90,000. Projecting a monthly Social Security benefit of $1250 for the same 40 years gives an annual Social Security benefit of $47,505. These projections take us to the subject's retirement age. The additional calculations required to determine the total amount required to meet specified retirement needs are summarized in Table 19.3.

The after-tax income need in the first year of retirement (age 65) is set at 75 percent of the individual's preretirement (age 64) after-tax income of $90,000. The after-tax need is projected at an inflation rate of 3 percent (column B) and then converted to a pretax need using the tax multipliers that incorporate the exemptions, deductions, and tax rates of the current law (columns C and D). Social Security benefits, projected at the same 3 percent rate as inflation (column E), are deducted from the pretax need (column F), assuming Social Security benefits will be fully taxable. If pension benefits are payable, they are deducted in the same manner. The remainder represents the pretax income gap. This projected pretax income need is discounted at 7 percent to reflect the anticipated earnings on the accumulation during distribution. This converts the projected before-tax income need into present values that can be summed to determine the present value of the future income need. The discounted inflation-adjusted before-tax income need is projected for a 25-year period. A shorter or longer period could have been selected, but the 25-year period seems reasonable. Based on the illustration's assumptions, $542,110 will provide the desired income.

The computations in the illustration are based on numerous assumptions. The program assumes income will increase at a specified rate and OASDI benefits will increase at the same rate. It further assumes tax rates will remain as under current law and the accumulation will earn 7 percent during the distribution period. Any (or all) of these variables are subject to change. This process is appealing because the planner can select the assumptions. If the planner is uncomfortable with a particular assumption, he or she can change it. Although summing the projection of inflation-adjusted needs is more complicated than converting a fixed monthly need into a principal amount, it will more likely yield a dollar amount that reflects the individual's needs.

TABLE 19.3 Inflation-Adjusted Retirement Need Projection

![]()

Planning the Retirement Accumulation

Once the accumulation required to finance retirement has been estimated, we turn to the second step in managing the retirement risk, which is to design and implement a plan to accumulate that fund. Because the problem here is the future value of current contributions, the concept of compounding is again useful. We can compute the future value of $1 ontributed each year to an accumulating fund and invested at a specified rate. Table 19.4 indicates the future value of a dollar invested each year at various rates of interest for various numbers of years. The future value of annual contributions is used to determine the contributions required to meet an accumulation target. Suppose, for example, that Jones decides she would like to accumulate $550,000 for retirement, which is 40 years in the future. Table 19.4 indicates that $1 contributed each year for 40 years at 7 percent interest is $213.61. To accumulate $550,000 in 40 years, Jones must contribute $2575 a year, or about $215 per month, that is

![]()

The perceptive student will note that this funding approach assumes a constant contribution level throughout the accumulation period. Because it may be assumed the individual's income and ability to save will increase over time, it seems more logical to base retirement funding on a variable (increasing) contribution. To achieve the same $550,000 accumulation with a contribution increasing at the same rate as income (i.e., 3 percent per year), the initial contribution required is $1757, increasing to $5564 in the last year before retirement. Since the initial $1800 represents 4.9 percent of the $36,000 monthly income, the individual might reasonably decide to contribute 5.0 percent of annual income to the retirement program, which will result in the contribution's automatic adjustment as income changes over his or her career. If the program's assumptions hold true, this program will produce an accumulation of $563,963 by the time the individual reaches age 65. Obviously, if income increases at a higher or lower rate than assumed, or if earnings on the accumulation are higher or lower than the assumed return rate, the accumulation will also vary.

TABLE 19.4 Future Value of $1 Annually for N Years at Various Rates

As previously discussed, life insurance and fixeddollar annuities should be considered as investment vehicles for the fixed-dollar component of the retirement accumulation. The tax-deferred nature of their investment earnings make them attractive instruments for the retirement accumulation. Because variable annuities share this tax-deferred advantage, they also deserve consideration as retirement funding instruments.

![]()

Planning the Retirement Distribution

The final step in planning for retirement is planning the distribution. Although determining the income amount needed for retirement and planning the manner in which these funds will be accumulated are critical steps, planning the manner in which the funds will be distributed is equally critical. In fact, decisions in this phase of the planning process may require adjustments in the earlier steps as the assumptions concerning needs and funding are tested against the assumptions in the distribution plan.

A number of decisions need to be addressed regarding the retirement accumulation distribution. The major decisions in this phase relate to the uncertainty regarding the retirees' life expectancy. They include the question of annuitizing the distribution, preservation of principal, and joint-and-survivor options.

Capital Retention versus Capital Liquidation Strategies The individual could have accumulated sufficient capital so the investment income alone may be adequate to provide the income required. In this case, he or she may elect to pursue a capital retention strategy and live on the investment income only. The choice between invading principal and living from the investment earnings will depend on the amount of principal available and the return earned on that principal.7 In measuring whether a capital retention strategy is feasible, however, the requirements of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) concerning required distributions must be considered.

Required Distributions For most persons, the accumulated principal in a retirement program (i.e., a pension, an IRA, or an annuity) will include an accumulation of untaxed contributions to the retirement program plus the untaxed earnings on those contributions. Because neither the contributions that created the accumulation nor the investment income on those accumulating contributions have been taxed, the IRC requires the accumulation be distributed and taxed as income to the participant. The requirements in this respect are specific and inflexible. Although distribution can be delayed until April 1 of the year following the year in which the participant reaches age 70½ or reaches actual retirement if later, at that time the accumulated funds must be paid out over a period that does not exceed the participant's life expectancy or the combined life expectancy of the participant and his or her beneficiary.8 IRS tables are used to calculate life expectancies. Failure to meet the IRC requirements regarding minimum distributions can result in a penalty tax equal to 50 percent of the amount by which the required minimum distribution exceeds the distribution that is made.9 Although one can defer distribution of the accumulated principal until age 70½, the distribution must be distributed over a shorter life expectancy and will probably be taxed at a higher marginal tax rate.

Life Annuities and Installment Distributions A first major decision is whether the individual will choose to withdraw retirement funds from the retirement accumulation in the form of a life annuity or in installments.10 Because the IRS requires a distribution no lower than one that would liquidate the principal over the individual's lifetime, many think of distributions in terms of a life annuity payout. As we saw in the last chapter, however, the distribution may be in the form of a life annuity, or it may be in the form of payments based on the particpant's expected lifetime (or the life expectancy of the participant and his or her beneficiary).

Although annuitizing the accumulation is one option, some may find the second approach (withdrawing income in installments based on life expectancy) more attractive. The appeal of this approach is it guarantees the entire accumulation will be paid out, even if the beneficiary should die prior to reaching his or her life expectancy. At the same time, if the individual outlives the expectancy, the principal will be exhausted and the individual will need another funding source. (This source could consist of funds that were withdrawn but not spent during the distribution period.)

Minimum Distribution Option If the retiree does not want to annuitize the principal or begin the withdrawal at retirement, some insurers offer a minimum distribution option. Under this option, the insurer will calculate and distribute the minimum income required each year to avoid the confiscatory (50 percent) tax on less than the minimum distributions required by the IRC. This allows the individual to preserve the principal while still meeting the withdrawal provisions of the IRC.

Variable Annuity Variable annuities may vary during the accumulation period and may be fixed during the payout period or variable during the accumulation period and payout periods. With the variable payout option, when the participant reaches retirement, the accumulation units are converted into a lifetime income of annuity units using a special mortality table for annuitants. The number of annuity units does not change over the annuitant's lifetime, but the income produced by each unit will reflect changes in the investments' value, with the current value of the annuity unit determining the beneficiary's income.11

We noted in the preceding chapter that changes in the value of annuity units do not always parallel changes in the price level. This was demonstrated rather dramatically during the 1970s, when the value of the College Retirement Equity Fund (CREF) accumulation unit dropped 43 percent over a three-year period, during which the CPI increased 18 percent. Discontinuities of this type illustrate the risks involved in the withdrawal decision. Again, as during the accumulation period, diversification seems a prudent strategy.

Variable Distributions under Nonvariable Annuities Although the variable annuity provides one approach to a variable distribution, this approach has problems as noted previously. Recognizing that inflation over a period of 20 to 30 years can severely erode the purchasing power of annuity payments, insurers provide optional modes of settlement under which the payments increase over time. Although the terminology differs among insurers, the basic distinction is between a standard payment method and a graded payment method.

Under the standard payment method, the beneficiary receives the contractually guaranteed interest plus allocated excess interest (i.e., the interest earnings that exceed the guaranteed rate). Under the graded payment method, the annuity payments include the guaranteed interest and principal but only a part of the excess interest. The remainder of the excess interest is reinvested to purchase additional annuity benefits for each future year. As additional purchases are made, the payments in future years are augmented by the proceeds from the additional annuities. Table 19.5 illustrates the difference in the payout rates under the standard payment method and the graded payment method.

TABLE 19.5 Standard and Graded Annuity Payments

The graded payment approach has risks. The annuitant sacrifices current income for future income. Although the income amount deferred will depend on the excess investment income level, under the assumptions embodied in the illustration, it will take at least 15 years for the annuitant to “catch up” and recover the income sacrificed by accepting the lower payments under the graded system. When interest is considered, the break-even point will be later.

With a part of the retirement payout invested in a variable annuity and a part invested in a fixed dollar annuity, the retiree can hedge against inflation and against fluctuations in the equity-based variable annuity. Payments will be less during periods of high inflation than under a program in which the entire principal is invested in equities, but it will be higher during periods in which equities are decreasing.

Single or Joint-Life Annuity A second major decision relates to the provision, if any, made for a surviving spouse. Under the provisions of Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), qualified pension plans must provide a joint-and-survivor life income option. Further, rejection of this option by a plan participant requires an affirmative rejection by the spouse. Although a joint-and-survivor benefit guarantees a continuing income to a surviving spouse at the primary annuitant's death, there is a cost. Because the joint-and-survivor option pays an income to the surviving spouse after the death of the first, payments during the joint lives of the spouses are lower than under a straight life annuity on a single person.

Pension Maximization The difference in the level of the monthly benefit under a joint-and-survivor annuity and a single life annuity led to a strategy known as pension maximization. This strategy is based on the ERISA requirement that pension participants accept a joint-and-survivor benefit unless the participant's spouse affirmatively rejects the option. Pension maximization developed as a means of maximizing the pension payout. Basically, the strategy consists of electing a single life annuity and using a part of the higher monthly benefit to purchase life insurance on the annuitant.

The amount of insurance should be sufficient to provide a lifetime annuity to the spouse equal to the survivorship benefit he or she would receive under the joint-and-survivor option. Under the right conditions, for instance when the premium for insurance on the annuitant spouse is less than the after-tax difference in the benefits, pension maximization can increase total benefits to a couple. Although any form of permanent life insurance on which the insured can continue the premium will work, the reversionary or survivorship annuity is ideally suited to this exposure.

Pension maximization is available only if the individual is insurable or if he or she has life insurance purchased at an earlier age still in force. In addition, for retirees who have employer-sponsored postretirement health insurance, a surviving spouse is generally able to continue the health care plan only if he or she is receiving a retirement benefit. For this situation, a joint-and-one-fourth or one-third survivor benefit may be an attractive compromise. This will guarantee a benefit to the spouse if he or she survives, so the health care benefits will continue.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

This chapter relies heavily on material presented in earlier chapters, and a few new concepts are introduced. Some concepts introduced earlier in connection with life insurance planning have application in retirement planning. The important new concepts that are introduced in the chapter are the following:

minimum distribution option

graded payment distribution

pension maximization

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. Describe the factors that create the retirement risk.

2. Identify and describe the two risks associated with retirement and briefly describe the strategies that may be used in addressing these risks.

3. Identify and describe the three steps in the retirement planning process.

4. Identify the three of retirement funding sources. In your opinion, how important and how dependable (certain) is each?

5. Distinguish between the capital retention strategy and a capital liquidation strategy. What factors will determine the individual's choice between these two strategies?

6. Describe the distribution requirements of the IRC with respect to retirement accumulations.

7. Describe the minimum distribution option offered by some insurers. What is the purpose of this option?

8. Describe the graded distribution option available in connection with pension and annuity distributions. What are this option's advantages and disadvantages?

9. What is pension maximization? Under what conditions is it feasible? Under what conditions is it advisable?

10. The estimate of postretirement income needs is usually based on a projected preretirement income level. Identify the two adjustments required in projecting the preretirement income to determine postretirement income needs.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. What is the underlying motivation for the capital conservation strategy in planning a retirement distribution? What is your personal opinion of this strategy?

2. Under the graded payment method of distribution for an annuity, the annuitant accepts a reduced payment during the distribution's early years in exchange for an increasing benefit. Can an individual achieve the same results by accepting the standard payment method and judiciously investing the amount by which the standard payment method benefit exceeds the graded payment method benefit? Why or why not?

3. You have graduated from college and commenced a successful career. In fact, the major problem you face is that your income has reached a point at which your combined state and federal marginal tax rate is nearly 50 percent. You are considering a flexible-premium deferred annuity as an investment, primarily because of the tax deferral on the accumulation. A friend has suggested you can achieve the same results by investing in tax-exempt bonds. Describe the factors you would consider in choosing between these alternatives.

4. Since superannuation is one of the risks to which the individual is exposed, an income protection plan should provide for the individual reaching retirement age. Considering the nature of cash value life insurance, variable annuities, and alternative vehicles for accumulation, what do you think is a logical and reasonable approach to the problem of saving for retirement?

5. Given the predicted financial difficulties facing the Social Security system, to what extent do you think Social Security benefits should be considered in the retirement planning process?

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Allen, Everett T., Joseph J. Melone, Jerry S. Rosenbloom, and Dennis F. Mahoney. Retirement Plans, 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2013.

Bajtelsmit, Vickie L. Personal Finance: Planning and Implementing Your Financial Goals. (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, 2005).

Black, Kenneth Black, Jr., Harold D. Skipper, and Kenneth Black III Life and Health Insurance, 14th ed. Lucretian, LLC, 2013.

Hallman, Victor G., and Jerry S. Rosenbloom. Personal Financial Planning. McGraw-Hill, 2003.

Little, David A., and Kenn Beam Tacchino. Financial Decisions for Retirement. Bryn Mawr, Pa.: The American College, 2005.

Leimberg, Stephan R., and John J. McFadden. Tools and Techniques of Employee Benefits and Retirement Planning, 12th ed. National Underwriter, 2011.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| AARP | www.aarp.org |

| Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards | www.cfp.net |

| Financial Planning Association | www.fpanet.org |

| Insured Retirement Institute | www.irionline.org |

| Internal Revenue Service | www.irs.gov |

| National Senior Citizens Law Center | www.nsclc.org |

| The American College | www.theamericancollege.edu/financial-planning |

| The Geneva Association | www.genevaassociation.org/programmes/life-and-pension |

![]()

1A 62-year-old retired worker who receives a Social Security benefit of, say, $1500 a month and accepts employment at $2000 a month, will lose $5520 in Social Security benefits. FICA taxes will take an additional $1836, and federal income tax will be about $1575, making total deductions of $8931 of the $24,000 in wages.

2Roth accounts have other potential advantages. First, they are not subject to the required minimum distribution beginning at age 70½. Second, individuals may contribute to a Roth IRA after age 70½, something not allowed for traditional IRA accounts. Roth contributions to a 401(k) or 403(b) plan are not subject to the income phase-out rules that apply to Roth IRAs.

3For an excellent discussion of the relative attractiveness of Roth and traditional plans, see Landon et al., “When Roth 401(k) and 403(b) Plans Outshine Traditional Plans,” Journal of Financial Planning, July 2006, Article 7, available at http://www.fpanet.org/journal/articles/2006Issues/jfp0706-art7.cfm

4See, for example, Percell, Patrick, “Older Works: Employment and Retirement Trends.” Congressional Research Service, September 16, 2009.

5A number of Web sites have calculators that can assist individuals with planning their retirement accumulation.

6Longevity insurance, an annuity deferred to a high age (such as 80 or 85), is a useful tool for this problem. Longevity insurance was discussed in Chapter 18.

7The higher the after-tax rate of return and the longer the period over which the capital will be withdrawn, the smaller the difference in monthly income produced by annuitizing the principal and preserving the capital intact. An individual in the 15 percent tax bracket with $500,000 invested at 8 percent could withdraw $40,000 annually ($34,000 after-tax) and preserve the $500,000 intact. If interest and the total principal are withdrawn over a 25-year period, the principal required to produce the same $34,000 annually is about $444,070. An additional $56,000 in principal will produce the required $34,000 after-tax annual income without invading the principal.

8IRC Section 401 (a)(9)(A).

9IRC Section 4974.

10Although the IRC also allows withdrawal in a lump sum, except in unusual cases, tax treatment of installment or annuity distributions will be more favorable to the insured.

11The monthly amount usually remains the same throughout the year because the value of the retirement annuity unit is usually established on an annual basis.