WEB–APPENDIX J

LEASE FINANCING

A lease is a contract over the term of which the owner of the property or equipment (the lessor) permits another entity (the lessee) to use it in exchange for a promise by the latter to make a series of payments. More equipment is financed today by equipment leases than by bank loans, private placements, or any other method of equipment financing. This is because management recognizes that earnings are derived from the use of an asset, not its ownership, and that leasing is simply an alternative financing method.

Given the importance of lease financing, we have devoted an appendix to this special financing arrangement. We compare leasing with financing the acquisition of equipment with borrowed funds. To appreciate the comparison, we begin by explaining the fundamentals of leasing. We then provide an analytical framework management can employ to compare equipment leasing to purchasing equipment with borrowed funds.

J.1 LEASING FUNDAMENTALS

A typical leasing transaction works as follows: The lessee first decides on the equipment needed. The lessee then decides on the manufacturer, the make, and the model. The lessee specifies any special features desired, the terms of warranties, guaranties, delivery, installation, and services. The lessee also negotiates the price. After the equipment and terms have been specified and the sales contract negotiated, the lessee enters into a lease agreement with the lessor. The lessee negotiates with the lessor on the length of the lease; the rental; whether sales tax, delivery, and installation charges should be included in the lease; and other optional considerations. After the lease has been signed, the lessee assigns its purchase rights to the lessor, which then buys the equipment exactly as specified by the lessee. When the equipment is delivered, the lessee formally accepts the equipment to make sure it gets exactly what was ordered. The lessor then pays for the equipment, and the lease goes into effect.

When all costs associated with the use of the equipment are to be paid by the lessee and not included in the lease payments, the lease is called a net lease or triple-net lease. Examples of such costs are property taxes, insurance, and maintenance. These costs are paid directly by the lessee and may not be deducted from the lease payments. At the end of the lease term, the lessee usually has the option to renew the lease, to buy the equipment, or to terminate the agreement and return the equipment. The options available to the lessee at the end of the lease are very significant in that the dimensions of such options determine the nature of the lease for tax purposes and the classification of the lease for financial accounting purposes.

J.1.1 Types of Equipment Leases

Nontax-oriented leases, most commonly referred to as conditional sale leases, transfer substantially all of the tax benefits and risks incidental to ownership of the leased property to the lessee and usually give the lessee a fixed-price bargain purchase option or renewal option not based on fair market value at the time of exercise. The U.S. tax code provides guidelines for a lease to be classified as a conditional sale lease for tax purposes. If a lease is classified as a conditional sale lease, the lessee treats the property as owned thereby entitling the lessee to depreciate the property for tax purposes, claim any tax credit that may be available, and deduct as an expense the imputed interest portion of the lease payments. The lessor under a conditional sale lease treats the transaction as a loan and, as explained later, cannot offer the low lease rates associated with a true lease because the lessor does not retain the tax benefits available to the owner of the equipment.

The true lease offers all of the primary benefits commonly attributed to leasing. Substantial financing advantages can potentially be achieved through the use of taxoriented true leases in which the lessor claims and retains the tax benefits of ownership and passes through to the lessee a portion of such tax benefits in the form of reduced lease payments. The lessor claims tax benefits resulting from equipment ownership such as tax depreciation deductions, and the lessee deducts the full lease payment as an expense. The lessor in a true lease owns the leased equipment at the end of the lease term. A tax-oriented true lease (also sometimes called a guideline lease) either contains no purchase option or has a purchase option based on fair market value.

The principal advantage to a lessee of using a true lease to finance an equipment acquisition is the economic benefit that comes from the indirect realization of tax benefits that might otherwise be lost because the lessee cannot use the tax benefits. This occurs when the lessee neither has a sufficient tax liability, nor expects to be able to fully use the tax benefits in the future if those benefits are carried forward.

If the lessee is unable to generate a sufficient tax liability to currently use all tax benefits, the cost of owning new equipment will effectively be higher than leasing the equipment under a true lease. Under these conditions, leasing is usually a less costly alternative than borrowing to buy the equipment because the lessor uses the tax benefits from the acquisition and passes on a portion of these benefits to the lessee through a lower lease payment.

The lower cost of leasing realized by a lessee throughout the lease term in a true lease must be weighed against the loss of the leased equipment's market value at the end of the lease term, referred to as the residual value. A framework for evaluating the tax and timing effects is presented later.

In the United States, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is well aware that parties to a leasing transaction may find it more advantageous from a tax point of view to characterize an agreement as a “lease” rather than as a conditional sale agreement. Therefore, guidelines have been established by the IRS to distinguish between a true lease and a conditional sale agreement.

There are two categories of true leases: single-investor leases (or direct leases) and leveraged leases. Single-investor leases are essentially two-party transactions, with the lessor purchasing the leased equipment with its own funds and being at risk for 100% of the funds used to purchase the equipment. The leveraged form of a true lease of equipment is the ultimate form of lease financing. The most attractive feature of a leveraged lease, from the standpoint of a lessee unable to use the depreciation tax benefits, is its low cost as compared to alternative methods of financing.1 A “leveraged lease” is always a true lease. The lessor in a leveraged lease can claim all of the tax benefits incidental to ownership of the equipment even though the lessor provides only 20% to 30% of the capital needed to purchase the equipment. This ability to claim the tax benefits attributable to the entire cost of the leased equipment and the right to 100% of the residual value provided by the lease, while providing and being at risk for only a portion of the cost of the equipment, is the “leverage” in a leveraged lease. This leverage enables the lessor in a leveraged lease to offer the lessee much lower lease rates than the lessor could provide under a single-investor nonleveraged lease.

J.2 COST OF LEASING

Leasing equipment is an alternative to purchasing. Because the lessee is obligated to make a series of payments, a lease arrangement resembles a debt contract. Thus, the cost advantages cited for leasing are often based on a comparison between leasing and purchasing using borrowed funds on an intermediate-term (maturity between 3 and 10 years) or long-term (maturity greater than 10 years) basis.

In a perfect capital market where transactions can be arranged costlessly, leasing (like any other financial intermediation function) would not in itself create economic value. For the lessee firm could costlessly arrange, on its own account, the same transactions as the lessor. However, as soon as transactions costs and the need for the lessor to earn a market rate of return on invested capital are admitted, it would appear that the firm using leasing transactions would be paying at least as much to the leasing firm as it would cost the firm to arrange the financing itself.

However, such costs might be offset if the lessor were able to claim tax advantages not available to the lessee. This situation could arise if, for example, the lessee had only a marginally profitable operation and hence could not claim the full tax shelter afforded by rapid depreciation of equipment as permitted under tax law. In these circumstances a profitable lessor might, if it were permitted to claim the full tax advantage, pass a portion on to the lessee and hence render the costs of leasing competitive with those of other forms of financing. Again, however, if financial markets are nearly perfect (apart from the tax and transactions cost considerations just mentioned), the foregoing argument would appear to suggest that the two types of financial arrangements would be equally costly when these markets attained an equilibrium.2

The cost of a true lease depends on the size of the transaction and whether the lease is tax-oriented or nontax-oriented. The equipment leasing market can be classified into the following three market sectors: (1) a small-ticket retail market with transactions in the $5,000 to $100,000 range; (2) a middle market with large-ticket items covering transactions between $100,000 and $5 million; and (3) a special products market involving equipment cost in excess of $5 million.

Tax-oriented leases generally fall into the second and third markets. Most of the leveraged lease transactions are found in the third market and the upper range of the second market. The effective interest cost implied by these lease arrangements is considerably below prevailing interest rates that the same lessee would pay on borrowed funds. Even so, the potential lessee must weigh the lost economic benefits from owning the equipment against the economic benefits to be obtained from leasing. Nontax-oriented leases fall primarily into the small-ticket retail market and the lower range of the second market. There is no real cost savings associated with these leases compared to traditional borrowing arrangements. In most cases, however, cost is not the dominant motive of the firm that employs this method of financing. In some cases, leasing may be the only funding source available to a firm.

From a tax perspective, leasing has advantages that lead to a reduction in cost for a company that is in a tax-loss-carryforward position and is consequently unable to claim tax benefits associated with equipment ownership currently or for several years in the future.

J.3 RISK OF OBSOLESCENCE AND DISPOSAL OF EQUIPMENT

When a firm owns equipment, it faces the possibility that at some future time the equipment may not be as efficient as more recently manufactured equipment. The owner may then elect to sell the original equipment and purchase the newer, more technologically efficient version. The sale of the equipment, however, may produce only a small fraction of its book value. By leasing, it is argued, the firm may avoid the risk of obsolescence and the problems of disposal of the equipment. The validity of this argument depends on the type of lease and the provisions therein. With a cancelable operating lease, the lessee can avoid the risk of obsolescence by terminating the contract. However, the avoidance of risk is not without a cost since the lease payments under such lease arrangements reflect the risk of obsolescence perceived by the lessor. At the end of the lease term, the disposal of the obsolete equipment becomes the problem of the lessor. The risk of loss in residual value that the lessee passes on to the lessor is embodied in the cost of the lease.

The risk of disposal faced by some lessors, however, may not be as great as the risk that would be encountered by the lessee. Some lessors, for example, specialize in short-term operating leases of particular types of equipment, such as computers or construction equipment, and have the expertise to release or sell equipment coming off lease with substantial remaining useful life. A manufacturer-lessor has less investment exposure since its manufacturing costs will be significantly less than the retail price. Also, it is often equipped to handle reconditioning and redesigning due to technological improvements. Moreover, the manufacturer-lessor will be more active in the resale market for the equipment and thus be in a better position to find users for equipment that may be obsolete to one firm but still satisfactory to another. IBM is the best example of a manufacturer-lessor that has combined its financing, manufacturing, and marketing talents to reduce the risk of disposal. This reduced risk of disposal, compared with that faced by the lessee, is presumably passed along to the lessee in the form of a reduced lease cost.

Nonetheless, financial institutions and other lessors are financing ever larger, more complex, and longer-lived assets, and uncertainty over the residual value of those assets is one of the biggest risks for lessors. A steel plant, for example, could have an estimated useful life of 30 years, but its actual useful life could be as short as 25 years or as long as 40 years. If the useful life of the plant turns out to be less than the lessor has projected, the lessor could suffer a loss on a lease that appeared profitable in the original analysis. For some types of assets there are abundant data to support estimates of residual value and for other types of assets there are very little data—particularly for new, unique, complex, or infrequently traded assets. The primary factors that affect residual value are the three components of depreciation: useful life (deterioration), economic obsolescence, and technological obsolescence. Rode, Fishbeck, and Dean (2002) suggest that lessors use the best information available to simulate the behavior of these three factors as well as the correlation among the three factors, based on probabilistic ranges of outcomes, to produce distributions of useful life curves, estimated values, and confidence intervals. Because conditions inevitably change over time, lessors should update their modeling frequently during the life of the equipment.

J.4 VALUING A LEASE: THE LEASE OR BORROW-TO-BUY DECISION

Now that we know what a lease is and the key role of the treatment of tax benefits and residual value in a lease transaction, we will show how to value a lease. Several economic models for valuing a lease have been proposed in the literature. The model used here requires the determination of the net present value of the direct cash flow resulting from leasing rather than borrowing to purchase an asset, where the direct cash flow from leasing is discounted using an adjusted discount rate.3 The model is derived by Myers, Dill, and Bautista (1976) from “the objective of maximizing the equilibrium market value of the firm, with careful consideration of interactions between the decision to lease and the use of other financing instruments by the lessee.” We will present and illustrate this model below. This lease valuation model is appropriate when the management anticipates that it can fully absorb the expenses associated with either financing alternative as they arise. In the next section, we describe and illustrate an extension of the lease valuation model developed by Franks and Hodges (1978) to deal with cases where a firm is currently in a non-tax-paying position but management believes it will commence paying taxes at some specified future date.

J.4.1 Direct Cash Flow from Leasing

When management elects to lease an asset rather than borrow money to purchase the same asset, this decision will have an impact on the firm's cash flow. The cash flow consequences, which are stated relative to the purchase of the asset, can be summarized as follows:

- There will be a cash inflow equivalent to the cost of the asset.

- The lessee may or may not forgo some tax credit. For example, prior to the elimination of the investment tax credit, the lessor could pass this credit through to the lessee.

- The lessee must make periodic lease payments over the life of the lease. These payments need not be the same in each period. The lease payments are fully deductible for tax purposes if the lease is a true lease. The tax shield is equal to the lease payment times the lessee's marginal tax rate.

- The lessee forgoes the tax shield provided by the depreciation allowance since it does not own the asset. The tax shield resulting from depreciation is the product of the lessee's marginal tax rate times the depreciation allowance.

- There will be a cash outlay representing the lost after-tax proceeds from the residual value of the asset.

For example, consider the capital budgeting problem faced by the Hieber Machine Shop Company. Management is considering the acquisition of a machine that requires an initial net cash outlay of $59,400 and will generate a future cash flow for the next five years of $16,962, $19,774, $20,663, $21,895, and $26,825. Assuming a discount rate of 14%, representing the company's weighted-average cost of capital, the net present value (NPV) for this machine is $11,540.

Let's assume that the following information was used to determine the initial net cash outlay and the cash flow for the machine:

Cost of the machine = $66,000

Tax credit4 = $6,600

Estimated pre-tax residual = $6,000 value after disposal costs

Estimated after-tax proceeds from residual value = $3,600

Economic life of the machine = 5 years

Depreciation is assumed to be as follows: 225

| Year | Depreciation deduction |

| 1 | $9,405 |

| 2 | 13,794 |

| 3 | 13,167 |

| 4 | 13,167 |

| 5 | 13,167 |

Additional annual expenses will be incurred by management by owning rather than leasing (i.e., the lease is a net lease). The lessor will not require the firm to guarantee a minimum residual value.

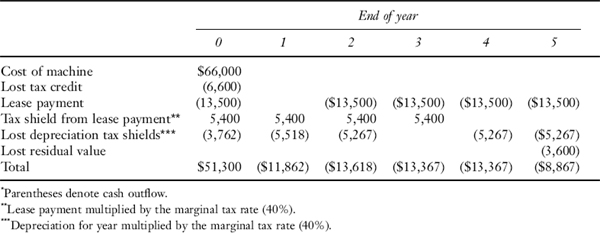

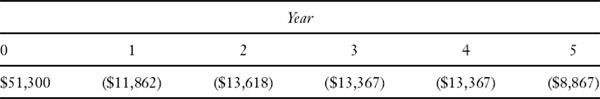

Table J.1 presents the worksheet for the computation of the direct cash flow from leasing rather than borrowing to purchase. The firm's marginal tax rate is assumed to be 40%. The direct cash flow is summarized below:

The direct cash flow from leasing was constructed assuming that (1) the lease is a net lease and (2) the tax benefit associated with an expense is realized in the tax year the expense is incurred. These two assumptions require further discussion.

First, if the lease is a gross lease instead of a net lease, the lease payments must be reduced by the cost of maintenance, insurance, and property taxes. These costs are assumed to be the same regardless of whether the asset is leased or purchased with borrowed funds. Where have these costs been incorporated into the analysis? The cash flow from owning an asset is constructed by subtracting the additional operating expenses from the additional revenue. Maintenance, insurance, and property taxes are included in the additional operating expenses. There may be instances when the cost of maintenance differs depending on the financing alternative selected. In such cases, an adjustment to the value of the lease must be made.

Second, many firms considering leasing may be currently in a non-tax-paying position but anticipate being in a tax-paying position in the future. The derivation of the lease valuation model presented in the next section does not consider this situation. It assumes that the tax shield associated with an expense can be fully absorbed by the firm in the tax year in which the expense arises. As noted earlier, Franks and Hodges (1978) provide an extension to the lease valuation model that will handle the situation of a firm currently in a non-tax-paying position.

TABLE J.1 WORKSHEET FOR DIRECT CASH FLOW FROM LEASING: HIEBER MACHINE SHOP COMPANY*

J.4.2 Valuing the Direct Cash Flow from Leasing

Because the lease displaces debt, the direct cash flow from leasing should be further modified by devising a loan that in each period except the initial period engenders a net cash flow that is identical to the net cash flow for the lease obligation; that is, financial risk is neutralized. Such a loan, called an equivalent loan, is illustrated later. Fortunately, it has been mathematically demonstrated that rather than going through the time-consuming effort to construct an equivalent loan, all that needs to be done is discount the direct cash flow from leasing by an adjusted discount rate. The adjusted discount rate can be approximated using the following formula: 6

Adjusted discount rate = (1 − Marginal tax rate) × (Cost of borrowing money)

The formula assumes that leasing will displace debt on a dollar-for-dollar basis.7

Given the direct cash flow from leasing and the adjusted discount rate, the NPV of the lease can be computed. We shall refer to the NPV of the lease as simply the value of the lease. A negative value for a lease indicates that leasing will not be more

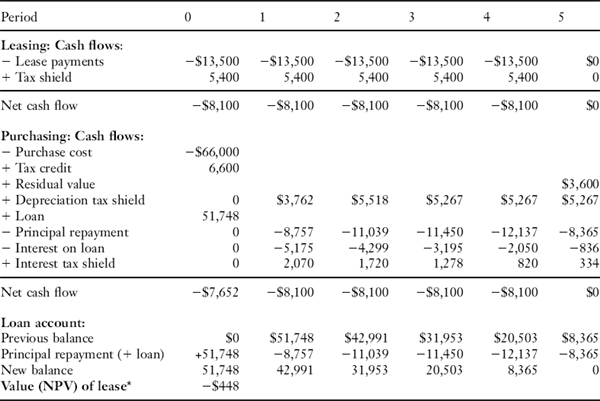

TABLE J.2 WORKSHEET FOR DETERMINING THE VALUE OF A LEASE

In order to evaluate the direct cash flow from leasing for the machine considered by the management of Hieber Machine Shop Company in our illustration, we must know the firm's cost of borrowing money. Suppose that the cost of borrowing money has been determined to be 10%. The adjusted discount rate is then found by applying the formula:

Adjusted discount rate = (1 − 0.40) × (0.10) = 0.06, or 6%

The adjusted discount rate of 6% is then used to determine the value of the lease. The worksheet is shown as Table J.2. The value of the lease is −$448. Hence, from a purely economic point of view, the machine should be purchased by management rather than leased. Recall that the NPV of the machine assuming normal financing is $11,540.

J.4.3 Concept of an Equivalent Loan

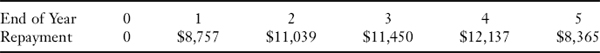

The value of the lease considered by management of Hieber Machine Shop Company was shown to be −$448. Suppose the management had the opportunity to obtain a $51,748 five-year loan at 10% interest with the following principal repayment schedule: 8

(Recall that the firm's marginal borrowing rate was assumed to be 10%.)

TABLE J.3 EQUIVALENT LOAN FOR LEASE VERSUS BORROW-TO-BUY DECISION FACED MANAGEMENT OF HIEBER

*Difference between the net cash flows in year 0 [−2$8,100 − (−2$7,652)].

Table J.3 shows the net cash flow for each year if the loan is used to purchase the machine. In addition to the loan, the firm must make an initial outlay of $7,652. The net cash flow for each year if the machine is leased is also presented in Table J.3. Notice that the net cash flows of the two financing alternatives are equivalent, with the exception of year 0. Therefore, the loan presented above is called the equivalent loan for the lease.

We can now understand why borrowing to purchase is more economically attractive for Hieber Machine Shop Company. The equivalent loan produces the same net cash flow as the lease in all years after year 0. Hence, the equivalent loan has equalized the financial risk of the two financing alternatives. However, the net cash outlay in year 0 is $7,652 compared to $8,100 if the machine is leased. The difference, −$448, is the value of the lease. Notice that the lease valuation model produced the same value for the lease without constructing an equivalent loan.

REFERENCES

Brealey, Richard, and Myers, Stewart. (1981). Principles of Corporate Finance. New York: McGraw Hill.

Franks, Julian R., and Stewart D. Hodges. (1978). “Valuation of Finance Contracts: A Note,” Journal of Finance 41: 657–669.

Miller, Merton H., and Charles W. Upton. (1976). “Leasing, Buying, and the Cost of Capital Services,” Journal of Finance 31: 761–786.

Myers, Stewart C. (1974). “Interactions of Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions: Implications for Capital Budgeting,” Journal of Finance 29: 1–26.

Myers, Stewart C., David A. Dill, and Alberto J. Bautista. (1976). “Valuation of Financial Lease Contracts,” Journal of Finance 31: 799–819.

Nevitt, Peter K., and Frank J. Fabozzi. (2002). Equipment Leasing. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Rode, David C., Paul S. Fishbeck, and Steve R. Dean. (2002). “Residual Risk and the Valuation of Leases under Uncertainty and Limited Information,” Journal of Structured and Project Finance

1 See Nevitt and Fabozzi (2002) for a further discussion of equipment leasing.

2 This argument is advanced in Miller and Upton (1976).

3 The adjusted discount rate technique presented in this appendix is fundamentally equivalent to and results in the same answer that is obtained by comparing financing provided by a loan that gives the same cash flow as the lease in every future period. This will be illustrated below. Although the adjusted discount rate technique is fundamentally equivalent to calculating the adjusted present value of a lease, it is less accurate. The adjusted present value technique, which will be described below takes into consideration the present value of the side effects of accepting a project financed with a lease. The adjusted present value technique was first developed in Myers (1974). The reason for a possible discrepancy between the solutions to the lease versus borrow-to-buy decision using the adjusted discount rate technique and adjusted present value technique is that different discount rates are applied where necessary in discounting the cash flow when the latter technique is used.

4 We use a tax credit in this illustration to show how the model can be applied should Congress decide to introduce some form of tax credit for capital investments in future tax legislation.

5 The depreciation schedule used in this illustration is for illustrative purposes only. The depreciation schedule to use at any given time is based on current tax law, which is subject to change. The depreciation in this example is based on a depreciable basis comprised of the cost of the asset, less one-half of the tax credit, or $66,000 − $3,300 = $62,700. The rates of depreciation for the five years, in order, are 15%, 22%, 21%, 21%, and 21%.

6 As noted by Brealey and Myers (1981, p. 629), “The direct cash flows are typically assumed to be safe flows that investors would discount at approximately the same rate as the interest and principal on a secured loan issued by the lessee.” There is justification for applying a different discount rate to the various components of the direct cash flow from leasing. economically beneficial than borrowing to purchase. A positive value means that leasing will be more economically beneficial. However, leasing will be attractive only if the NPV of the asset assuming normal financing is positive and the value of the lease is positive, or if the sum of the NPV of the asset assuming normal financing and the value of the lease is positive.

7 See Brealey and Myers (1981, p. 634). The formula must be modified, as explained later, if the lessee believes that leasing does not displace debt on a dollar-for-dollar basis.

8 The loan payments are determined by solving for the set of repayments and interest each period that would result in the value of purchase (accompanied by a loan) being equivalent to leasing.