Other Contemporary Theories of Motivation

Self-determination theory and goal-setting theory are well supported contemporary theories of motivation. But they are far from the only noteworthy OB theories on the subject. Self-efficacy, reinforcement, equity/organizational justice, and expectancy theories reveal different aspects of our motivational processes and tendencies.

Self-Efficacy Theory

Self-efficacy theory, also known as social cognitive theory or social learning theory, refers to an individual’s belief that he or she is capable of performing a task.42 The higher your self-efficacy, the more confidence you have in your ability to succeed. So, in difficult situations people with low self-efficacy are more likely to lessen their effort or give up altogether, while those with high self-efficacy will try harder to master the challenge.43 Self-efficacy can create a positive spiral in which those with high efficacy become more engaged in their tasks and then, in turn, increase performance, which increases efficacy further.44 One study introduced the additional explanation that self-efficacy may be associated with a higher level of focused attention, which may lead to increased task performance.45

Goal-setting theory and self-efficacy theory don’t compete; they complement each other. As Exhibit 7-4 shows, employees whose managers set difficult goals for them will have a higher level of self-efficacy and set higher goals for their own performance. Why? Setting difficult goals for people communicates your confidence in them.

Exhibit 7-4

Joint Effects of Goals and Self-Efficacy on Performance”

Source: Based on E. A. Locke and G. P. Latham, “Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35-Year Odyssey,” American Psychologist 57, no. 9 (2002): 705–17.

Increasing self-efficacy in yourself

The researcher who developed self-efficacy theory, Albert Bandura, proposes four ways self-efficacy can be increased:46

Enactive mastery.

Vicarious modeling.

Verbal persuasion.

Arousal.

The most important source of increasing self-efficacy is enactive mastery—that is, gaining relevant experience with the task or job. The second source is vicarious modeling—becoming more confident because you see someone else doing the task. Vicarious modeling is most effective when you see yourself as similar to the person you are observing. The third source is verbal persuasion: we become more confident when someone convinces us we have the skills necessary to be successful. Motivational speakers use this tactic. Finally, arousal increases self-efficacy. Arousal leads to an energized state so we get “psyched up,” feel up to the task, and perform better. But if the task requires a steady, lower-key perspective (say, carefully editing a manuscript), arousal may in fact hurt performance even as it increases self-efficacy because we might hurry through the task.

Intelligence and personality are absent from Bandura’s list, but they too can increase self-efficacy.47 People who are intelligent, conscientious, and emotionally stable are so much more likely to have high self-efficacy that some researchers argue self-efficacy is less important than prior research suggested.48 They believe it is partially a by-product in a smart person with a confident personality.

Influencing self-efficacy in others

The best way for a manager to use verbal persuasion is through the Pygmalion effect, a term based on the Greek myth about a sculptor (Pygmalion) who fell in love with a statue he carved. The Pygmalion effect is a form of self-fulfilling prophecy in which believing something can make it true. Here, it is often used to describe “that what one person expects can come to serve a self-fulfilling prophecy.”49 An example from research should make this clear. In studies, teachers were told their students had very high IQ scores when, in fact, they spanned a range from high to low. Consistent with the Pygmalion effect, the teachers spent more time with the students they thought were smart, gave them more challenging assignments, and expected more of them—all of which led to higher student self-efficacy and better achievement outcomes.50 This strategy has been used in the workplace too, with replicable results and enhanced effects when leader-subordinate relationships are strong.51

Training programs often make use of enactive mastery by having people practice and build their skills. In fact, one reason training works is that it increases self-efficacy, particularly when the training is interactive and feedback is given afterward.52 Individuals with higher levels of self-efficacy also appear to reap more benefits from training programs and are more likely to use their training on the job.53

Reinforcement Theory

Goal setting is a cognitive approach, proposing that individuals’ purposes direct their actions. Reinforcement theory, in contrast, takes a behavioristic view, arguing that reinforcement conditions behavior. The two theories are clearly philosophically at odds. Reinforcement theorists see behavior as environmentally caused. You need not be concerned, they would argue, with internal cognitive events; what controls behavior are reinforcers—any consequences that, when they immediately follow responses, increase the probability that the behavior will be repeated.

Reinforcement theory ignores the inner state of the individual and concentrates solely on what happens when he or she takes some action. Because it is not concerned with what initiates behavior, it is not, strictly speaking, a theory of motivation. But it does provide a powerful means of analyzing what controls behavior, and this is why we typically consider reinforcement concepts in discussions of motivation.54

Operant conditioning/behaviorism and reinforcement

Operant conditioning theory, probably the most relevant component of reinforcement theory for management, argues that people learn to behave a certain way to either get something they want or to avoid something they don’t want. Unlike reflexive or unlearned behavior, operant behavior is influenced by the reinforcement or lack of reinforcement brought about by consequences. Reinforcement strengthens a behavior and increases the likelihood it will be repeated.55

B. F. Skinner, one of the most prominent advocates of operant conditioning, demonstrated that people will most likely engage in desired behaviors if they are positively reinforced for doing so; that rewards are most effective if they immediately follow the desired response; and that behavior that is not rewarded, or is punished, is less likely to be repeated. The concept of operant conditioning was part of Skinner’s broader concept of behaviorism, which argues that behavior follows stimuli in a relatively unthinking manner. Skinner’s form of radical behaviorism rejects feelings, thoughts, and other states of mind as causes of behavior. In short, under behaviorism people learn to associate stimulus and response, but their conscious awareness of this association is irrelevant.56

Social-learning theory and reinforcement

Individuals can learn by being told or by observing what happens to other people, as well as through direct experience. Much of what we have learned comes from watching models—parents, teachers, peers, film and television performers, bosses, and so forth. The view that we can learn through both observation and direct experience is called social-learning theory.57

Although social-learning theory is an extension of operant conditioning—that is, it assumes behavior is a function of consequences—it also acknowledges the effects of observational learning and perception. People respond to the way they perceive and define consequences, not to the objective consequences themselves.

Equity Theory/Organizational Justice

Ainsley is a student working toward a bachelor’s degree in finance. In order to gain some work experience and increase her marketability, she has accepted a summer internship in the finance department at a pharmaceutical company. She is quite pleased with the pay: $15 an hour is more than other students in her cohort receive for their summer internships. At work she meets Josh, a recent graduate working as a middle manager in the same finance department. Josh makes $30 an hour and is dissatisfied. Specifically, he tells Ainsley that, compared to managers at other pharmaceutical companies, he makes much less. “It isn’t fair,” he complains. “I work just as hard as they do, yet I don’t make as much. Maybe I should go work for the competition.”

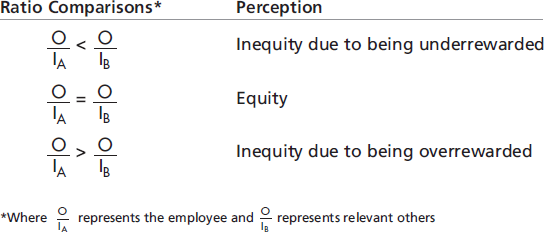

How could someone making $30 an hour be less satisfied with his pay than someone making $15 an hour and be less motivated as a result? The answer lies in equity theory and, more broadly, in principles of organizational justice. According to equity theory, employees compare what they get from their jobs (their outcomes such as pay, promotions, recognition, or a bigger office) to what they put into it (their inputs such as effort, experience, and education). Employees therefore take the ratio of their Outcomes (O) to their Inputs (I) and compare it to the ratio of others, usually someone similar like a coworker or someone doing the same job. This is shown in Exhibit 7-5. If we believe our ratio is equal to those with whom we compare ourselves, a state of equity exists and we perceive our situation as fair.

Exhibit 7-5

Equity Theory

Based on equity theory, employees who perceive inequity will make one of six choices:58

Change inputs (exert less effort if underpaid or more if overpaid).

Change outcomes (individuals paid on a piece-rate basis can increase their pay by producing a higher quantity of units of lower quality).

Distort perceptions of self (“I used to think I worked at a moderate pace, but now I realize I work a lot harder than everyone else”).

Distort perceptions of others (“Mike’s job isn’t as desirable as I thought”).

Choose a different referent (“I may not make as much money as my brother-in-law, but I’m doing a lot better than my Dad did when he was my age”).

Leave the field (quit the job).

Equity theory has support from some researchers, but not from all.59 However, although equity theory’s propositions have not all held up, the hypothesis served as an important precursor to the study of organizational justice, or more simply fairness, in the workplace.60 Organizational justice is concerned broadly with how employees feel authorities and decision makers at work treat them. For the most part, employees evaluate how fairly they are treated, as shown in Exhibit 7-6. Let’s discuss some of the topics related to organizational justice next.

Exhibit 7-6

Model of Organizational Justice

Distributive Justice

Distributive justice is concerned with the fairness of outcomes, such as the pay and recognition that employees receive. Outcomes can be allocated in many ways. For example, raises can be distributed equally among employees, or they can be based on which employees need money the most. However, as we discussed about equity theory, employees tend to perceive their outcomes are fairest when they are distributed equitably.

Does the same logic apply to teams? At first glance, it would seem that distributing rewards equally among team members is best for boosting morale and teamwork—that way, no one is favored. However, a study of U.S. National Hockey League teams suggests otherwise. Differentiating the pay of team members on the basis of their inputs (how well they performed in games) attracted better players to the team, made it more likely they would stay, and increased team performance.61

Procedural Justice

Although employees care a lot about what outcomes are distributed (distributive justice), they also care about how they are distributed. While distributive justice looks at what outcomes are allocated, procedural justice examines how.62 For one, employees perceive that procedures are fairer when they are given a say in the decision-making process. Having direct influence over how decisions are made, or at the very least being able to present our opinion to decision makers, creates a sense of control and helps us to feel empowered (we discuss empowerment more in the next chapter).

If outcomes are favorable and individuals get what they want, they care less about the process, so procedural justice doesn’t matter as much when distributions are perceived to be fair. It’s when outcomes are unfavorable that people pay close attention to the process. If the process is judged to be fair, then employees are more accepting of unfavorable outcomes.63 Why is this the case? Think about it. If you are hoping for a raise and your manager informs you that you did not receive one, you’ll probably want to know how raises were determined. If it turns out your manager allocated raises based on merit and you were simply outperformed by a coworker, then you’re more likely to accept your manager’s decision than if raises were based on favoritism. Of course, if you get the raise in the first place, then you’ll be less concerned with how the decision was made.

Informational Justice

Beyond outcomes and procedures, research has shown that employees care about two other types of fairness that have to do with the way they are treated during interactions with others. The first type is informational justice, which reflects whether managers provide employees with explanations for key decisions and keep them informed of important organizational matters. The more detailed and candid managers are with employees, the more fairly treated those employees feel.

Though it may seem obvious that managers should be honest with their employees and not keep them in the dark about organizational matters, many managers are hesitant to share information. This is especially the case with bad news, which is uncomfortable for both the manager delivering it and the employee receiving it. Explanations for bad news are beneficial when they take the form of excuses after the fact (“I know this is bad, and I wanted to give you the office, but it wasn’t my decision”) rather than justifications (“I decided to give the office to Sam, but having it isn’t a big deal”).64

Interpersonal Justice

The second type of justice relevant to interactions between managers and employees is interpersonal justice, which reflects whether employees are treated with dignity and respect. Compared to the other forms of justice we’ve discussed, interpersonal justice is unique in that it can occur in everyday interactions between managers and employees.65 This quality allows managers to take advantage of (or miss out on) opportunities to make their employees feel fairly treated. Many managers may view treating employees politely and respectfully as too “soft,” choosing more aggressive tactics out of a belief that doing so will be more motivating. Although displays of negative emotions such as anger may be motivating in some cases,66 managers sometimes take this too far. Consider former Rutgers University men’s basketball coach Mike Rice, who was caught on video verbally and even physically abusing players, and was subsequently fired.67

Justice Outcomes

After all this talk about types of justice, how much does justice really matter to employees? A great deal, as it turns out. When employees feel fairly treated, they respond in a number of positive ways. All the types of justice discussed in this section have been linked to higher levels of task performance and citizenship behaviors such as helping coworkers, as well as lower levels of counterproductive behaviors such as shirking job duties. Distributive and procedural justice are more strongly associated with task performance, while informational and interpersonal justice are more strongly associated with citizenship behavior. Even more physiological outcomes, such as how well employees sleep and the state of their health, have been linked to fair treatment.68

Despite all attempts to enhance fairness, perceived injustices are still likely to occur. Fairness is often subjective; what one person sees as unfair, another may see as perfectly appropriate. In general, people see allocations or procedures favoring themselves as fair.69 So, when addressing perceived injustices, managers need to focus their actions on the source of the problem. In addition, if employees feel they have been treated unjustly, opportunities to express frustration have been shown to reduce the desire for retribution.70

Ensuring Justice

How can an organization affect the justice perceptions and rule adherence of its managers? This depends upon the motivation of each manager. Some managers are likely to calculate justice by their degree of adherence to the justice rules of the organization. These managers will try to gain greater subordinate compliance with behavioral expectations, create an identity of being fair to their employees, or establish norms of fairness. Other managers may be motivated in justice decisions by their emotions. When they have a high positive affect and/or a low negative affect, these managers are most likely to act fairly.

It might be tempting for organizations to adopt strong justice guidelines in attempts to mandate managerial behavior, but this isn’t likely to be universally effective. In cases where managers have more rules and less discretion, those who calculate justice are more likely to act fairly, but managers whose justice behavior follows from their affect may act more fairly when they have greater discretion.71

Culture and Justice

![]() Across nations, the same basic principles of procedural justice are respected, in that workers around the world prefer rewards based on performance and skills over rewards based on seniority.72 However, inputs and outcomes are valued differently in various cultures.73

Across nations, the same basic principles of procedural justice are respected, in that workers around the world prefer rewards based on performance and skills over rewards based on seniority.72 However, inputs and outcomes are valued differently in various cultures.73

![]() We may think of justice differences in terms of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (see Chapter 5). One large-scale study of over 190,000 employees in 32 countries and regions suggested that justice perceptions are most important to people in countries with individualistic, feminine, uncertainty-avoidance, and low power-distance values.74 Organizations can tailor programs to meet these justice expectations. For example, in countries that are highest in individualism, such as Australia and the United States, competitive pay plans and rewards for superior individual performance may enhance feelings of justice. In countries dominated by uncertainty avoidance, such as France, fixed-pay compensation and employee participation may help employees feel more secure. The dominant dimension in Sweden is femininity, so relational concerns are considered important there. Swedish organizations may therefore want to provide work–life balance initiatives and social recognition. Austria, in contrast, has a strong low power-distance value. Ethical concerns may be foremost to individuals in perceiving justice in Austrian organizations, so organizations there may want to openly justify inequality between leaders and workers and provide symbols of ethical leadership.

We may think of justice differences in terms of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions (see Chapter 5). One large-scale study of over 190,000 employees in 32 countries and regions suggested that justice perceptions are most important to people in countries with individualistic, feminine, uncertainty-avoidance, and low power-distance values.74 Organizations can tailor programs to meet these justice expectations. For example, in countries that are highest in individualism, such as Australia and the United States, competitive pay plans and rewards for superior individual performance may enhance feelings of justice. In countries dominated by uncertainty avoidance, such as France, fixed-pay compensation and employee participation may help employees feel more secure. The dominant dimension in Sweden is femininity, so relational concerns are considered important there. Swedish organizations may therefore want to provide work–life balance initiatives and social recognition. Austria, in contrast, has a strong low power-distance value. Ethical concerns may be foremost to individuals in perceiving justice in Austrian organizations, so organizations there may want to openly justify inequality between leaders and workers and provide symbols of ethical leadership.

Expectancy Theory

One of the most widely accepted explanations of motivation is Victor Vroom’s expectancy theory.75 Although it has critics, most evidence supports the theory.76

Expectancy theory argues that the strength of our tendency to act a certain way depends on the strength of our expectation of a given outcome and its attractiveness. In practical terms, employees are motivated to exert a high level of effort when they believe that it will lead to a good performance appraisal, that a good appraisal will lead to organizational rewards such as salary increases and/or intrinsic rewards, and that the rewards will satisfy their personal goals. The theory, therefore, focuses on three relationships (see Exhibit 7-7):

Exhibit 7-7

Expectancy Theory

Effort–performance relationship. The probability perceived by the individual that exerting a given amount of effort will lead to performance.

Performance–reward relationship. The degree to which the individual believes performing at a particular level will lead to the attainment of a desired outcome.

Rewards–personal goals relationship. The degree to which organizational rewards satisfy an individual’s personal goals or needs and the attractiveness of those potential rewards for the individual.77 Expectancy theory helps explain why a lot of workers aren’t motivated on their jobs and do only the minimum necessary to get by.

As a vivid example of how expectancy theory can work, consider stock analysts. They make their living trying to forecast a stock’s future price; the accuracy of their buy, sell, or hold recommendations is what keeps them in work or gets them fired. But the dynamics are not simple. Analysts place few sell ratings on stocks, although in a steady market as many stocks are falling as are rising. Expectancy theory provides an explanation: Analysts who place a sell rating on a company’s stock have to balance the benefits they receive from their accuracy against the risks they run by drawing that company’s ire. What are these risks? They include public rebuke, professional blackballing, and exclusion from information. When analysts place a buy rating on a stock, they face no such trade-off because, obviously, companies love it when analysts recommend that investors buy their stock. So the incentive structure suggests the expected outcome of buy ratings is higher than the expected outcome of sell ratings, and that’s why buy ratings vastly outnumber sell ratings.78

Does expectancy theory tend to work? Some critics suggest it has only limited use and is more valued where individuals clearly perceive effort–performance, and performance–reward, linkages.79 Because few individuals do, the theory tends to be idealistic. If organizations actually rewarded individuals for performance rather than seniority, effort, skill level, and job difficulty, expectancy theory might be more valid. However, rather than invalidating it, this criticism can explain why a significant segment of the workforce exerts low effort on the job.