Chapter 19

The Rerecording Stage

Predubbing and the Final Mix

“Rolling the first rehearsal on a dubbing stage is weeks of blood,

sweat, and tears followed by seconds of sheer terror!”

By the time Arnold Schwarzenegger had completed principal photography on Predator, he was well on his way to becoming a big-screen veteran of numerous action-adventure and fantasy motion pictures, most of which bristled with special effects and robust soundtracks (Conan the Barbarian, Commando, Red Sonja, and The Running Man). Inevitably, though, when he screened the finished pictures, they sounded nothing like he remembered during principal photography. Arnold soon realized that something very powerful and magical happened to a picture between the time shooting wrapped and the time of the cast-and-crew screening, and he was determined to figure out what that was—this thing called postproduction.

Arnold followed Predator through the postproduction process filled with cutting edge CGI (computer-generated image) special effects as well as a high-energy soundtrack of music and dynamic sound effects. He thought that if he understood the magical contributions of postproduction, he could select those future entertainment projects with the most potential. He would become empowered.

Indeed, several months later Arnold found himself on the Zanuck Stage at 20th Century Fox with the rerecording mixers as they painstakingly worked through the umpteenth predub of sound effects for the destruction of a rebel camp. The tail pop “bleeped,” and the mixer leaned over and pressed the talkback button to speak to the recordist in the machine room. He told him to take this predub down and to put up a fresh roll for the next dedicated sound effects pass. Knowing it would take the crew several minutes, the mixer pushed his chair back from the giant dubbing console and glanced at Schwarzenegger, who was taking in the entire mixing process. “Well, Arnold, whad'ya think of postproduction now?”

Arnold considered the question, and then, in his Bavarian accent, replied, “Well, I'll tell you. I spent weeks in the jungle, hot and dirty and being eaten alive by insects, and now, here we are, for weeks going back and forth and back and forth on the console—I think I liked the jungle better.”

RERECORDING

Rerecording is the process in which separate elements of various audio cues are mixed together in a combined format, and set down for preservation in a form either by mechanical or electronic means for reproduction. In simpler terms, rerecording, otherwise referred to as mixing or dubbing, is where you bring carefully prepared tracks from sound editorial and music and weave them together into a lush, seamless soundtrack.

With little variation, the basic layout of mixing stages is the same. The stage cavity, or the physical internal size of the stage itself, however, varies dramatically in height, width, and length, determining the spatial volume. Sound facilities that cater to theatrical release product generally have larger stages, duplicating the average size of the movie theaters where the film likely will be shown. Sound facilities that derive their business from television format product have smaller dubbing stages, as there is no need to duplicate the theatrical environment when mixing for home television presentation, whether for network, cable broadcast, or direct-to-video product. In all cases, though, these rooms have been carefully acoustically engineered to deliver a true reproduction of the soundtrack without adding room colorization that does not exist in the actual track.

The mixing console (or the board) is situated approximately two-thirds the distance from the screen to the back wall of the dub stage. The size and prowess of the mixing console also reflect the kind of dub stage—theatrical or television. A theatrical stage has a powerful analog or digital console able to service 100 to 300 audio inputs at once. The console shown in Figure 19.1 is a Neve Logic 2 console. This particular console has 144 inputs with 68 outs. The board is not as long as traditional consoles, which can stretch between 30 and 40 feet. Digital consoles do not need to be as long because they go down as well as side-by-side. Each fader module controls more than one audio input in a layered assignment configuration, allowing mixing consoles to be much bigger in their input capacity without being as wide as a football field. This input expansion is not reserved only for digital consoles.

I can tell how mindful a sound facility is to the needs of the supervising sound editor and the music editor by whether it has included supervisor desks on either end of the console. As a supervising sound editor, I want to be seated right next to the effects mixer, who is usually working on the right third of the console, so that I can talk to the head mixer and effects mixer in a quiet and unobtrusive manner. In this position, I also am able to maintain a constant eye on the proceedings and to make editorial update needs or channel assignment notations in my own paperwork without being disruptive. Supervising sound editor Greg Hedgepath has his sound effects session called up on one of the two Pro Tools stations on stage. This places him in an ideal position to communicate with the mixers as they mix the material, as well as to make any fixes or additions right on the spot. It also saves the effort of taking down a reel and sending it back to editorial for a quick fix that can be made in moments.

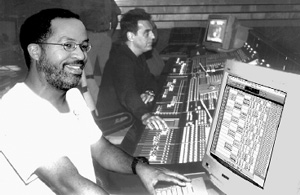

Figure 19.1 Rerecording mixer John S. Boyd, twice nominated for an Academy Award for best sound on Empire of the Sun and Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, works on a Neve Logic 2 console. Photo by David Yewdall.

The same is true for the music editor. He or she wants to sit next to the music mixer, who is usually situated on the left third of the console. From this position, the music editor not only can communicate with the music mixer quietly, but also can listen to the audio reproduction from the speakers in the same basic position as the music mixer.

Just behind the console is the credenza, a bank of rack-mounted gear and patchbays easily utilized by the mixers by just turning about in their chairs. When I walk onto an unfamiliar stage, I first glance at the console to see the platform used by the sound house, but I next study the credenza very closely. Here, one can see what kinds of extra bells-and-whistles gear the mixer has at command without resorting to equipment rentals from an outside supplier, which obviously affects the hourly stage rental rate. Looking over the patchbay in the credenza, an experienced eye gets an immediate feel for the layout and prowess of the machine room as well as for the contemporary facets of the stage engineering.

THE CREDENZA

Fancy face plates and sexy color schemes do not impress me. Many modern equipment manufacturers go to a great deal of trouble to give their equipment sex appeal through clever design or flashy image. The experienced craftsperson knows better, recognizing established names and precise tools that are the mainstays of the outboard gear arsenal that produces the firepower for the mixer.

Figure 19.2 Head mixer André Perreault (center) helms the mixing chores of The Wood with his sound effects mixer Stan Kastner working the material on his left. Supervising sound editor, Greg Hedgepath (foreground) checks over the channel assignments. Photo by David Yewdall.

The mixing console is either hardwired to a patchbay in the stage credenza or hardwired to a patchbay up in the machine room. Either way, the patchbay is critical to giving full flexibility to the mixer or recordist when patching the signal path of any kind of playback equipment (whether film, tape, or digital hard drive) to the mixing console. The mixer can then assign sends and returns to and from other gear, whether internal or outboard, to enhance, harmonize, add echo, vocode, compress, dip filter, and many other functions not inherent in the fader slide assemblies of the console.

Once the signal path has passed through the fader assembly, the mixer assigns the signal to follow a specific bus back to the machine room, where the mixed signal is then recorded to a specific channel of film, tape, or a direct-to-disk digital drive.

Figure 19.3 The credenza holds outboard signal processing gear and signal path patchbays just behind the mixing console in reach of the rerecording mixers.

It Can Seem Overwhelming

The first time you approach a mixing console can be very intimidating, especially if it is a feature film mixing stage, where you have a console with three mixers operating it.

Take a moment and look at it carefully. It is all about signal path, groupings, and routing. You see a desk with dozens of automated faders and a sea of tall slender knobs for equalization. First of all, you can reduce the complexity down tremendously when you realize that the console is composed of dozens of fader/EQ components that are all the same. If you analyze and understand channel 1, then you understand the majority of the rest of the board.

These fader/EQ components are long computer-board-style assemblies that fasten into place by a couple of set screws and can be removed and replaced in a few short minutes. The two basic components of the fader/EQ assembly are the fader (volume control) and the parametric equalizer.

The fader is a sliding volume control that moves forward (away from the rerecording mixer) to increase volume or back (toward the rerecording mixer) to reduce volume. Almost all fader controls today are automated—that is, they can be engaged to remember the rerecording mixer's moves and will play back those moves exactly the same unless the move program data is updated by the mixing console's software.

You will note that the fader moves forward, or up, hence the cliché that you hear on the rerecording stage all the time, “Up is louder.”

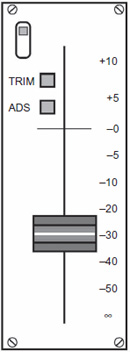

Figure 19.4 Fader pot.

This book will not deem to sit in judgment on whether that term, usually used in the heat of frustration, is meant as a sincere moment of instruction or an insult to the mixer's capacity to fulfill the client's soundtrack expectation.

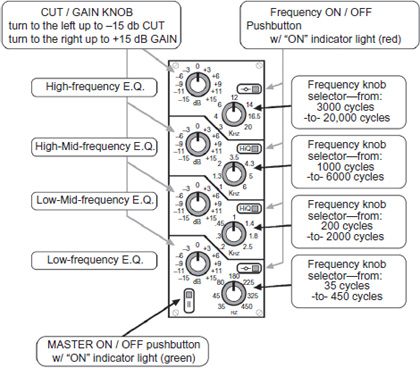

In front of (or above) the fader is the equalization array. This is usually a classic GML parametric configuration such as the one shown above. Some low-end parametric assemblies only offer three bands of influence. The one shown above is four-band, and others may have as many as five or six. Each area (the low-frequency, low-midrange, high-midrange, and high-end) has its own volume attenuation as well as a frequency selector, showing the apex of influence.

The next thing to understand is that a three-position console, supporting the music mixer (usually on the left side), the head mixer (usually in the center), and the effects mixer (usually on the right side), is really three consoles that for the majority of the time work as three separate consoles that happen to be connected together as one.

The mixers are paying attention to their own assignments (dialog, music, and effects) and their designated audio signals are passing their own sections of the console onto either their own dedicated recorder or onto to their own dedicated channel assignments of a multitrack machine or nonlinear workstation. They just happen to be interlocked together and playing through the same speakers, which give the illusion that it is all one soundtrack—at least for the present.

Figure 19.5 Parametric equalizer.

Figure 19.6 The mixing team on the John Ford Rerecording Stage at 20th Century Fox. Head mixer Paul Massey oversees the progress as David Giammarco, the sound effects mixer, works in the foreground on material that supervising sound editor Hamilton Sterling has brought to mix on For Your Consideration directed by Christopher Guest. Photo by John LeBlanc.

After the supervising sound editor, editor, director, producer(s), executive producers, studio executives, and distribution executives have signed off on the “final mix,” only then will the Dolby, SDDS, and DTS techs be brought in to oversee the 2-track print master and the various digital format masters. At that point, the soundtracks (dialog, music, and effects) truly reside together as a single theatrical soundtrack. But that comes after weeks of blood, sweat, and tears and other unmentionable spoken events and sometimes even fisticuffs have taken place.

For the record, though fisticuffs is never endorsed by any audio guild or technical manual, it has, from time to time, been the final argument for how a soundtrack is conceived.

THE MIXERS

Head Mixer

With few exceptions, the head mixer is also the dialog mixer, usually running the stage from the center seat. This gives the head mixer ideal physical positioning in the dubbing stage cavity to listen to and evaluate the mix. Almost always, the head mixer is involved with each step of the predubbing process. Only with the mega-soundtracks now being predubbed on two or more stages simultaneously is the head mixer not a part of each predubbing pass before the entire reel is mounted for a rehearsal for final mix.

During the final mix, the head mixer intercedes and instructs the music mixer and sound effects mixer to raise, lower, or tweak certain cues. Mixing teams often stay together for years because they reach a level of unspoken communication as they come to know each member's tastes and work habits. The head mixer has the last word in the balance and dynamic strategies of the final mix.

Effects Mixer

Most sound effects mixers work from the right chair. During the predubbing process, they often work with the head mixer as a team. During the dialog predub, the effects mixer may help the dialog mixer with extra peripheral tracks if the cut dialog track preparation is unusually wide. By doing this, the dialog mixer can concentrate on the primary onscreen spoken words. On lower budget projects, where stage time utilization is at a premium, the effects mixer may run backgrounds or even Foley as the dialog mixer predubs his dialog tracks. In this way, the dialog mixer knows how far to push the equalization or to change the level to clean the production tracks. He or she knows what to count on from backgrounds or Foley to bridge an awkward moment and make the audio action seamless.

When the dialog predubs are completed, the head mixer then assists the effects mixer in sound effects predubbing. At this point, the effects mixer runs the stage, as the sound effects predubs are his responsibility. The dialog (head) mixer helps the effects mixer in any way to make the most expeditious use of stage time, as only so much time is budgeted and the clock is ticking.

Music Mixer

The music mixer rarely comes onto the stage during the predubbing process. The music mixer may be involved in music mixdowns, where an analog 2” 24-track or a digital multichannel session master may need to be rerecorded down to mixdown cues for the music editor to cut into sync to picture. He or she may be asked to mix the music down to 6- or 8-channel Pro Tools sessions. There are still some music mixers who do not like mixing straight to a nonlinear platform, insisting instead on mixing down to a 6-channel 35 mm fullcoat or 6 or 8 channels of a 2” 24-track tape, and then having the transfer department handle the transfer chores to a nonlinear audio format.

Times Have Changed

In the old days, the head mixer was God. Directors did not oversee the mixing process as they do today; the head of the sound department for the studio did that. The director would turn over the director's cut of the picture and move on to another project. He or she would see the finished film and mixed soundtrack several months later.

Head mixers dictated what kind of material went into a soundtrack and what would be left out. Often, the supervising sound editor was an editorial extension of the will of the head mixer. When a head mixer did not like the material, it would be bounced off the stage, and the director would tell the sound editors to cut something different; sometimes the director would dictate the desired sound effects series. This is unheard of today. Not only do directors follow the process through to the end, often inclusive of the print master, but they have a great deal of say in the vision and texture of the soundtrack.

Supervising sound editors are no longer just an extension of the head mixer, but come onto the stage with a precise design and vision they already have been developing; from the Foley artist and sound designer on up through their sound editorial staff, they have taken a far more commanding role in the creative process.

Many film projects are brought to a particular stage and mixing team by the supervising sound editor, thereby making the mixing crew beholden to his or her design and concept wishes. This is a bad thing, although, in many instances, a greater degree of collaborative efforts does occur between sound editorial and rerecording mixers with an already established relationship. Many signal-processing tasks, once strictly the domain of mixers, are now being handled by sound designers and even sound editors, who are given rein to use their digital processing plug-ins.

Whole concepts now come to the stage virtually predubbed in effect-groupings. Whip pans on lasers and ricos are just not cost-effective to pan-pot on the rerecording stage by the sound effects mixer, and in some cases so many sound effects must move so fast that a mixer just cannot pan-pot them properly in real time. These kinds of whip pans are built in by the sound editor at the workstation level. (The lasers from Starship Troopers, discussed in Chapter 13, are a case in point.)

As discussed in prior chapters, supervising sound editors and their sound designers handle more and more signal processing, including equalization and filtering. Just a few years ago, these acts would have been grounds for union fines and grievances; now they take place every day in every sound facility. Some sound editorial services are even doing their own predubbing, bringing whole sections of predubbed material rather than hundreds of tracks of raw sound. Some of this is due to financial and schedule considerations, some due to sound design conceptuality.

A Vital Collaboration

And then, every once in a blue moon, you find yourself working with a mixer who talks a good game, but when the chips are down he just “once-easy-overs” your stuff and basically mushes out any design hopes that you have built into your material, or he or she just does not have the passion to go the extra distance to really make it sing.

While supervising the sound editorial and mixing of Near Dark, Kathryn Bigelow's first feature film as director, we were predubbing the dialog, which needed a lot of extra massaging with equalization and signal-processing gear. It takes a little work to make a silk purse out of a sow's ear of mediocre location mishmash. Kathryn was a superb quick study, anxious to learn anything and everything she could to empower herself to be a better director.

I was becoming increasingly annoyed at the lack of assistance that the lead mixer was giving to help her out, both for the dialog track of her present film and to her personally for her future pictures. I went out into the lobby and grabbed the phone and called my shop. I told my first assistant to build a bogus set of sound units, complete with intercut mag stripe (with no sound at all) and a full cue sheet advertising dozens of seemingly important cues.

The predub pass showed up at the stage by mid-afternoon, and with the usual setup time the machine-room crew mounted the units within 20 minutes. The head mixer got a full green light status, so he rolled picture. The first cue passed through with no audio being heard.

Standard procedure was to back up and try it again, checking your console to make sure that nothing was muted, turned off, and misrouted. The cue went through again, and of course, with no audible result. The mixer turned to his credenza to make sure that the patch cords were firmly in place and in the right order. All of this takes time, precious time; the clock on a dubbing stage is always ticking and every tick costs money.

The mixer rolled the projector again and the cue went by again, and again (of course) there was no audio. The mixer glanced at me. I shrugged innocently. He pressed the talkback button to speak to his machine room. “Is effects 4 in mag?”

The recordist had to get up out of his booth and walk around into the machine room to physically find “effects 4” and see if the mag track was on over the playback head. Now, just by looking at the mag track itself, the recordist assumes that there is sound on it. Wouldn't you? Then he walked all the way back into his booth to answer back. “Yes, it's in mag.”

The mixer rolled the cue again—with the same silent results. He hit the talkback button. “Bloop the track.”

The recordist had to get up and walk around into the machine room, grab the “tone loop” off the hook, find “effects 4,” work the tone loop mag in between the mag track and the head, and pull it up and down to cause the tone to rub against the mag track. Loud “vrip-vrip-vrip” of tone modulation blasted out the speaker. That meant the patch cords were good, the routing was good, nothing was muted, and we were getting signal. The mixer shot a suspicious glance over at me. I shrugged. Standard procedure when you did not get a proper playback of a cue was to make a note and bring it back as a sweetener later, so I turned and scribbled a seemingly legitimate note to bring “effects 4” as a sweetener later.

The mixer pushed on to the next cue. The next cue did not play. Again, the mixer stopped to check the signal path for “effects 5” as he had before. Again, he ran the cue and again it played nothing. He shot me another suspicious scowl. I just gazed at him with an innocent expression.

Again he had to have his recordist walk back and “bloop” the track, and again the “vrip-vrip-vrip” tone pounded the room. I shrugged and turned to write another bogus notation for a sweetener. The mixer rolled to the next cue, and again it passed over the heads without any audio response. By now the mixer had had enough. He yanked back all of his faders with a smack and whirled around to me. “Okay, Yewdall—what?!”

I quietly put my pencil down and folded my hands while Kathryn watched. My eyes met the mixer's rage and I quietly but firmly replied, “Let's understand one another. This is a collaborative effort. I am only as good as how you make my material sound and you are only as good as the material I bring you. God blessed you with the arms of an orangutan and I would think that you could at least reach up to your parametrics and help the director achieve her vision.”

The mixer leaped up and stomped off the stage to the head of the sound department, with the expectation that I would get my *#! chewed out and hopefully removed from the project. Instead I was called into the head of the sound department's office to watch the mixer get his *#! chewed out and be reminded how the winds of postproduction power had shifted.

The mixer and I walked back to the stage together to forge a working agreement that we could both survive together and deliver the best soundtrack possible to a rising new director.

PREDUBS: TACTICAL FLOW

Predubbing is the art of keeping options open. You want to distill the hundreds of your prepared sound elements down into more polished (not final polish) groupings. By doing this, you can put up all your basic elements, such as dialog, ADR, group walla, Foley, backgrounds, sound effects, and music, so that you can rehearse and “final” the reel as one complete soundtrack.

Rerecording Mixing Flowchart

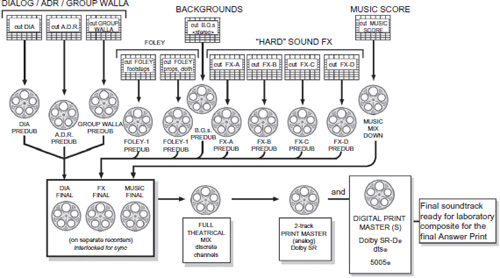

As shown in Figure 19.7, predubbing is broken into logical groupings. Because dialog is the most important component of a film soundtrack and must sound as smooth and seamless as possible, predub it first, especially if you have a limited amount of time in the schedule for predubbing. Ideally, we always would have enough time to predub all our cut material fully and properly. Not only is this not the case, it is the exception.

Figure 19.7 The rerecording mixing flow chart.

Since I could write an entire book on mixing, encompassing budgeting, scheduling, and techniques, here I simply discuss one fairly common formula. Four-week dubbing schedules are normal for medium-budgeted feature films in Hollywood. Naturally, tactics differ, depending on whether you mix the single mixer approach or the mixer team approach. This example is of a mixer team approach to mixing, using a two-mixer formula. Provided that sound editorial was not put into an insane schedule crunch and that the normal mixing protocol can be implemented, I generally find the following to be a safe tried-and-proven battle plan.

Four-Week Mixing Schedule

• |

Dialog predubbing: 5 days (dialog with BGs); 4 days (if dialog only) |

• |

Background predubbing: 2 days |

• |

Foley predubbing: 2 days |

• |

Sound effects predubbing: 3 days |

• |

Final mix: 7 days |

• |

Playback and fixes: 1 day |

• |

Print master: 1 day |

• |

Foreign M&E: 1 day |

Please note that this schedule does not allow for a digital sound mix and mastering process. This gets you through predubbing, final mix, continuity playback along with a conservative number of fixes (if you have a greater list, add additional days to your mixing schedule), print master, and foreign M&E for the analog version.

This is a guide used over and over in generalities. The “what-ifs” factor a hundred variants, and no two motion pictures are ever the same. You will have a mixer who prefers to predub dialog along with the Foley, rather than a mixer who wants backgrounds. Then you will have the purist mixer who wants it to be predubbed without anything camouflaging the material. (I endorse the purist philosophy, by the way.)

A client discusses the mixing schedule for his or her project with me (the supervising sound editor). Naturally, this conversation is held months after the film has been scheduled and budgeted, so it is not a discussion about how to schedule the mixing process. Rather, it becomes a retrofit of “This is all that we have budgeted for—how do you think we should utilize it?”

With this is mind, I always counsel that more possible predubbing makes the final mixing process go much more smoothly and more quickly. You can adopt one of two tactics in deciding how to balance the number of days to predub, as opposed to how many days to final. First, you can take a 15-day mixing schedule and set aside 5 days for predubbing (at a lower per-hour rate) and have 10 days to final (at a higher per-hour rate). The producer and director like the idea of having a full day per reel to final; that is how the big shows are done, so they want the same. This means much less material is predubbed, and that, during the final mix, you stop more often to reset equalization or fix transitions between sound cues because not enough time was devoted to predub the material properly. With the stage cost at full rate, tensions on the stage quickly develop.

The second, more logical approach is to give a larger portion of the 15 days to predubbing. I have often suggested that 9 days be devoted to predubbing, meaning you must final 2 reels a day. This is often done, as the smart client knows, if the material was more thoroughly predubbed because the final mixing goes much more smoothly and more quickly. As discussed in Chapter 4, the success or failure of a soundtrack is in your hands long before the postproduction sound craftspeople ever get a chance to touch it.

That does not mean that good soundtracks are not achieved in shorter schedules or for fewer budget dollars. One False Move is a perfect example of this. This picture had only 9 days to mix, inclusive of predubbing. One False Move looks like a much more expensive movie than its budget would suggest. Jeffrey Perkins at International Recording was set as the head rerecording mixer. He had won the Academy Award for Best Sound on Dances with Wolves, and both Carl Franklin (director) and Jesse Beaton (producer) of One False Move considered it a fabulous opportunity to have Jeffrey handle the mixing chores. The dubbing schedule happened to fall in the slow period during the Cannes Film Festival, which gave the added value of a lower hourly stage rate.

Even so, the schedule was only 9 days, all inclusive. Jeffrey and I had not worked together before, and such a short schedule concerned him. I offered to go over to International to talk with him about dubbing tactics. I grabbed the cue sheet envelope for reel 7 on my way out the door, as I thought he would learn more about what to expect in sound editing preparation by seeing the cue sheets laid out.

I spread the cue sheets to reel 7 across his dubbing console, starting with dialog and ADR, then Foley, backgrounds, and finally sound effects. In moments he began to relax, seeing how I had not spread the sound assembly too wide, should we have to forego some predubbing needs, hang the cut material, and final the reel from raw cut sound units.

The first thing we both agreed to was persuading the client to take one day from final mixing and use it for predubbing. We knew it would make for an easier and faster final mix. Jeffrey prioritized what he would predub—first, second, third. When we ran out of time and had to commence finals, at least the priority chores would be completed.

As it turned out, we did not need to compromise anything on the rerecording mix of One False Move. Although the mixing schedule was extremely tight, the client listened to our advice and counseling and, for the most part, took it. All the cut material ended up being predubbed. Nothing was left to hang raw. We set a methodical schedule for finals, and, with very little exception, lived up to it. We predubbed, executed the final mix as well as shot the 2-track print master, and made the M&E in 9 days.

THE NEW CENTURIONS OF THE CONSOLE

Today's technologies dictate the evolution of how we may do things—new tools, new protocols, new delivery requirements—but not the change of an art form. If you learn your art form you will always be the artist, understanding how to create an audio event that moves an audience in a desired emotional way. All of us are and will always be learning new tools, many of which we have discussed in the previous chapters of this book. But the disciplines, how and why we work with the audio medium the way we do to create our art form, does not change.

Figure 19.8 Zach Seivers (his company is Snap Sound) rerecording a feature film in his 5.1 room at Herzog-Cowen in North Hollywood. Photo by John LeBlanc.

The reality is that the majority of sound rerecording is not executed in the traditional theatrical rooms, but in smaller venues. Most of these rooms have been sleekly designed to offer a lot of bang-for-the-buck, keeping the overhead nut as low as possible without sacrificing or compromising the audio art form that the mixer(s) continually strive to achieve.

One of today's bright new talents, working in such a way, is Zach Seivers. He explains his philosophy:

Being able to adapt and evolve is probably the most important trait a person entering the industry can have. Producers have to answer to the bottom line. Ultimately, at the end of the day, the job has to be done professionally, efficiently, and under budget.

The tools and techniques one adopts can put that person years ahead of the competition. With just a little bit of ingenuity and willingness to step outside the standards and conventions everyone else is following, it's possible to discover a whole new and better way of doing things. Just think, what would have happened if 10 years ago Pro Tools wasn't adopted to edit, design, and eventually mix sound for films? We most definitely wouldn't have the kinds of soundtracks we do today!

Creating a soundtrack on a low budget is much more challenging than when you have money to throw at the problem, as we discussed in Chapter 14. The partner to the editorial team who has to figure out how to bring the material to the mixing console in such a way that it can be mixed within the budget and time restraints is, of course, the rerecording mixer. Without question, the collaboration and interdependency with each other, the sound editor and the rerecording mixer, is magnified when there is no latitude to waste money.

Figure 19.9 Close view of the automated console, with the Pro Tools session on the monitor to the rerecording mixer's left. Photo by John LeBlanc.

Most of these new mixing venues are strictly run by a single mixer, mainly for budgetary reasons. That said, there is something to be said for single mixer style of rerecording a track. The mixer knows every detail, every option in the dialog production material as he or she balances backgrounds, Foley, and sound effects against the music score because he or she has predubbed the dialog track and knows what is and is not there to utilize.

It is a natural evolution that sound designer/editors are mixing more and more of their own material. Many do their own predubbing, taking their material to a rerecording stage only for the final mixing process.

More and more are becoming editor/mixers, not just because technology has offered a more fluid and seamless transition from the spotting notes to the final mix stems, but the obvious continuity of creative vision, where a supervising sound editor may end up mixing his own show. There is a lot to be said for this, but it cannot be realistically accomplished on the super-fast postproduction schedules that studios often crush the sound crews to achieve. During most of the rerecording process of Dante's Peak, for instance, there were four separate rerecording stages working on various predubbing and finaling processes simultaneously.

WHO REALLY RUNS THE MIX?

It never fails to amaze me who really has the last word on a dubbing stage. On the miniseries Amerika, Jim Troutman had to work on both Stages 2 and 3 of Ryder Sound simultaneously. His rerecording mixers down on Stage 3 were predubbing, while another team of mixers made the final mix upstairs on Stage 2. Ray West and Joe Citarella had just completed predubbing the action sequences on a particular reel and were about to play it back to check, when a tall gentleman in a business suit entered, patted Jim Troutman on the shoulder, and sat in a nearby make-up chair. The two mixers glanced at the executive-looking man with slight concern and then commenced the playback.

When lights came up at the end of the reel, Jim asked the businessman what he thought. He shrugged and was a little timid about giving his opinion. With a little encouragement, he spoke his mind. “I thought the guns were a little low and mushy during the shoot-out.”

Immediately, the mixers spun the reel down to the scene, took the safeties off the predub with the gun effects, and started remixing the weapon fire. That finished, they asked what else bothered him. Cue by cue, they coaxed his ideas and concerns, immediately running down to each item and making appropriate fixes. After speaking his mind, he stood up and smiled, patted Jim on the shoulder again with appreciation for letting him sit in and then turned and left.

Once the door closed, the mixers turned to Jim. “Who was that?!”

Jim smiled. “Who, John? Oh, he's my accountant.”

The two mixers sat frozen in disbelief, then started laughing in relief.

Not all “control” stories end with relief and humor. I supervised a science-fiction fantasy that was filled with politics and egocentric behavior. Reel 5 was a major special-effects-filled action reel. Everyone had arrived promptly to start rehearsals at 9:00 A.M., as it promised to be a long day. To stay on schedule, we would need to final reel 5 and get at least halfway through reel 6.

Everyone had arrived—everyone, that is, except for the producer. The mixing team had gotten right in and commenced rehearsing the reel. At the end of the first rehearsal pass, the head mixer glanced about, looking for the producer. He still had not arrived. The reel was spun back to heads, whereupon they commenced another rehearsal pass. By 11:00 A.M. the crew had completed four rehearsal passes of the reel, and still the producer was not there. The head mixer looked to me. “We're starting to get stale. Let's make this reel. He'll be walkin’ through the door any minute.” I agreed. The mixer pressed the talkback button and informed his recordist to put the three Magna-Tech film recorders on the line and to remove the record safeties. We rolled. Foot by foot, the mixers ground through the reel. The last shot flickered off the screen, and three feet later the tail pop beeped.

Suddenly the stage door burst open as the producer entered. “Hey, guys, what are we doing?”

“We've just finaled reel 5 and are about to do a playback,” the head mixer replied matter-of-factly.

The producer's demeanor dropped like a dark shroud. “Really? Well, let's hear this playback.”

You could just feel it coming. The machine room equipment wound down and stopped as the Academy leader passed by. Then reel 5 rolled. Almost every 10’ the producer had a grumbling comment to make. At first the head mixer was jotting down notes, but after the first 200’ he set his pencil down.

As the reel finished, the lights came up. The producer engaged in a nonstop dissertation about how the mixing crew had completely missed the whole meaning and artistic depth of the reel. I studied the head mixer as he listened to the producer talk. Finally, the head mixer had had enough. He turned and hit the talkback button, telling the recordist to rerack at Picture Start and prepare to refinal the reel—they would be starting over.

Satisfied that he was proving his command and control, the producer rose and headed out the side door to get a cup of coffee and a donut. I watched the head mixer as he quietly leaned over to the console mic. He pressed the talkback button and whispered. “Take these three rolls down and put them aside. Put up three fresh rolls for the new take.” He noticed me eavesdropping and winked.

We worked hard on the new final of reel 5, slugging it out for the next two and a half days. We had given up any hope of keeping to the original dubbing schedule, as the issue of politics and egocentric behavior had gone way over the top. I knew the stage alone was costing $700 per hour. Over the course of the extra two and a half days, the overage bill for the stage would easily run close to $16,000.

Finally, the last scene flickered away, and the tail pop beeped. The producer rose from his make-up chair and strode toward the side door to get a fresh cup of coffee. “Awright guys, let's do a playback of that!”

I watched the head mixer as he leaned close to the console mic and alerted the recordist. “Take these three rolls off and put the other three rolls from the other day back up. Thank you.” He calmly turned to meet my gaze with a grin.

The producer returned, and the lights lowered. For 10 minutes, reel 5 blazed across the screen, playing the original mix done three days before. The producer slapped the armrest of his chair. “Now that is how I wanted this reel to sound!”

PROPER ETIQUETTE AND PROTOCOL

Protocol is the code of correct conduct and etiquette observed by all who enter and spend any amount of time, either as visitor or client-user, on a rerecording stage. It is vitally important that you pay strict attention to the protocol and etiquette understood in the professional veteran's world. Just because you may be the director or producer does not mean you are suddenly an expert in how to mix sound. Clients are often on the stage during predubbing processes when they really should not be there. They speak up and make predubbing level decisions without a true understanding of what goes into making the material and particularly what it takes to predub the material properly to achieve the designed effect.

One particular director who makes huge-budget pictures thinks he truly understands how good sound is made. I had spent weeks designing and cutting intricate interwoven sound effect cues, which, once mixed together, would create the audio event making the sequence work. The sound effects mixer had never heard these sounds before, and I spread several layers of cue sheets across his console. One vehicle alone required 48 soundtracks to work together simultaneously. The mixer muted all but the first stereo pair, so that he could get a feel for the material. Instantly, the director jumped up. “That's not big enough; it needs more depth, more meat to it.”

Knowing his reputation during the predubbing process from other sound editors, I turned to him. “This sequence is a symphony of sound. Our effect mixer has simply introduced himself to the first viola. Why don't you wait until he has tuned the entire orchestra before you start criticizing?” Booking the dubbing stage does not necessarily give the client keys to the kingdom. On countless occasions, the producer books a sound facility, and then proceeds to push the dubbing crew to the brink of mutiny. The adage that “money talks” is not an excuse to disregard protocol and etiquette.

I was dubbing a temp mix for a test audience screening on a Wesley Snipes picture. It wasn't that the director and his committee of producers had nit-picked and noodled the temp mix to death. It wasn't that the schedule was grueling and demanding. All postproduction professionals understand compressed schedules and high expectation demands. It was the attitude of the three producers, the inflection and tone of their comments, that ate away at the head mixer.

During a reel change break, I overheard the head mixer talking to the facility director in the hall. Once the temp mix was finished, the mixer would have nothing to do with any further temp dub or the final mix for this picture, regardless of its high profile. The facility director was not about to force his Academy Award winning mixer to do something that he did not want to do, so he informed the client that the stage had just been block-booked by another studio, forcing the client to look elsewhere for sound facility services.

Usually, the etiquette problem is much simpler than that. It boils down to who should speak up on a rerecording stage and who should remain quiet and watch politely, taking anything that must be said out to the hallway for private interaction with either the director or producer.

Teaching proper protocol and etiquette is extremely difficult because the handling of dubbing chores has changed so much that entire groups of young sound editors and sound designers are denied the rerecording stage experience. A few years ago, before the advent of nonlinear sound editing, access to the rerecording stage was far more open, an arena in which to learn. You prepared your material, brought it to the stage, and watched the mixer run it through the console and work with it. You watched the mixer's style and technique. You learned why you should prepare material a certain way, what made it easier or harder for the mixer, and what caused a breakdown in the collaborative process.

I always had the sound editor, who personally cut the material, come to the stage to sit with the mixers and me. After all, this was the person who knew the material best. We also would call back to the shop late in the afternoon for the entire crew to sit in on the playback of each reel on stage. The sound crew felt a part of the process, a process that today inhibits such togetherness. Somehow we must find a way to get editorial talent back on the dubbing stage. Somehow we must make the rerecording experience more available to up-and-coming audio craftspeople, who must learn and understand the intricacies of the mixing process.

PRINT MASTERING

On completion of the final mix are three 35 mm rolls of fullcoat per reel, or there are discrete digital stems to a master hard drive in the machine room. The three basic elements of the mix—dialog, music, and sound effects—are on their own separate rolls. When you lace these three rolls together in sync and set the line-up tones so the outputs are level matched, the combined playback of these three rolls produces a single continual soundtrack. If not mixing to 35 mm film fullcoat, MMR-8s, or Pro Tools HD, you can mix to a hard drive inside the mixing console system, if the console is so equipped. Regardless of the medium, the rerecording mixers still want dialog, music, and effects in their own controlled channels.

Once the final mix is complete, the head mixer sets up the room for a playback of the entire picture. Many times, as you mix a film reel by reel, you feel you have a handle on the continuity flow and pace; however, only by having a continuity playback running of the entire film with the final mix will you truly know what you have. Much can be learned during a continuity playback, and you will often make notes to change certain cues or passages for various reasons.

Several days prior to completing the final mix, the producer arranges with Dolby or for a tech engineer to be on hand with their matrixing box and supervise the print mastering of the final mix. Although many theaters can play digital stereo soundtracks, such as Dolby SR-D, SDDS, or DTS, always have the analog stereo mix on the print.

Do not attempt to have discrete optical tracks for the component channels; Dolby and Ultra Stereo offer a matrix process that encodes, combining the left, center, right, and split surround channels of the final mix into two channels. When the film is projected in the theater, this matrixed 2-channel soundtrack is fed into a Dolby decoder box prior to the speaker amplification, where the two matrixed channels are decoded back out into the proper left, center, right, and surround channels. On many occasions a theater that offers a digital sound presentation has a technical malfunction with the digital equipment for some reason. Sensors in the projection equipment detect the malfunction and automatically switch over to the analog 2-track matrixed track.

The tech engineer sets up the matrix encoding equipment and sits with the head mixer, paying strict attention to peak levels on extremely loud passages. The analog soundtrack is an optical track and has a peak level that must be carefully adjusted, what used to be called making optical.

There may be moments in the print-mastering process where the tech engineer will ask the mixer to back up and lower a particular cue or passage because it passed the maximum and clashed.

For some, the print-mastering phase is the last authorship of the soundtrack. Many a smart music composer who has not been on stage for the final mix shows up for the print master; he or she knows that changes and level balances are still possible, and many films end up with a different balanced soundtrack than the final mix. Hence, the supervising sound editor never leaves the print-mastering process as just a transfer job left to others.

Pull-Ups

An overlooked finalizing task that must be done before the soundtrack can be shipped to the laboratory is having the pull-ups added. What is a pull-up anyway? Technically, it is the first 26 frames of sound of the reel that has been attached to the end of a previous reel. This makes smoother changes in theatrical projection when one projector is finished and must change over to the next projector.

Because of electronic editing, precise pull-ups have become a fairly sloppy procedure. I see more and more mixers electronically “shooting” the pull-ups. This indicates laziness on the part of the supervising sound editor rather than being the fault of the rerecording mixer.

You do not need to put pull-ups on every reel, unless the show was mixed pre-built in an A-B configuration. If the print master is in A-B configuration, then, of course, every reel needs to have a pull-up.

The mixer has the print master of the following reel mounted. The line-up tones are critical, and great pains are taken to ensure that the “X-Copy” transfer of the print master is an exact duplicate. The mixer includes the head pop and several feet of the opening shot. The recordist makes sure that each pull-up is carefully tagged to show from which reel it came. The supervising sound editor and assistant usually cut the pull-ups in the change room of the sound facility, as the print master should not be moved offsite for contract and insurance reasons. If the show was not mixed in A-B configuration, then the supervisor and assistant do so now.

Electronic editing unfortunately made many editing services extremely sloppy in the head- and tail-pop disciplines. I have seen pops slurred in replication over several frames. The worst I have seen was a head pop that slurred 8 frames. Now where in the world do you get a precise position for sync?

If you pay close, disciplined attention to the head and tail pops, you will have an easy time finding the precise perforations between which to cut. You can take satisfaction and ease in being 1/96 of a second accurate, rather than trying to decide which frame pop to believe.

First, I take the roll of pull-ups the mixer transferred for me. I place it in a synchronizer and roll down until I pass a reel designation label; shortly thereafter are tones and then the head pop. I stop and carefully rock the film back and forth under the sound head, being absolutely assured of the leading edge of the pop. I use my black Sharpie to mark the leading edge and then count 4 perforations and mark the back edge. I rock the film back and forth gently to see if the back edge is truly 4 perforations long. I open the synchronizer gang and pick the film out; then I roll the synchronizer so the 0 frame is at the top. I zero out the counter and roll down to 9’. I place the marked pop over the 0 frame and roll down to 12 + 00. This is the exact leading edge of the soundtrack for this reel. Using the black Sharpie, I mark the frame line. Just in front of the frame line, I write from which reel this piece of sound comes. I then cut off 3’ or 4’ of the incoming sound and hang it in the trim bin until I need it. After I prepare all my pull-up sections, I commence building the A-B rolls.

I always roll the picture in the first gang alongside the print master. This way, I can physically see and verify the relationship of picture to soundtrack. I always locate the head pop first. I seat it exactly on the 0 of the synchronizer, with the footage counter at 9’. I then roll backward toward the start mark. Head start marks are often one or two perforations out of sync. This is unconnected to how the recordist is doing his or her job. It is related to the way the film machines settle in when put on the line. That is why the 9’ head pop is critical, as its position is the only true sync start mark. From it, you can back up and correct the position of the start mark label.

Once this is done, I roll down through the reel to the last frame of picture. Be sure you are using a 2000’ split reel or 2000’ projection reel on which to wind the reels. I mark the frame line with a black Sharpie and then mark past it with a wavy line to denote waste. I then take the next reel and seat the head pop at 9 + 00. I roll down to 12 + 00 and mark the top of the frame with a black Sharpie. Using a straight-edged (not an angle!) Rivas butt splicer, I cut the 2 frame lines, then splice the backside of the fullcoat with white 35 mm perforated splicing tape. Never use a splicer that punches its own holes in splicing tape during this procedure—never, never!

I then continue to roll down through the second reel, now attached to the first, until I reach the last frame of picture. I mark the bottom of the frame line of the last frame. I then pull the pull-up of the next reel and cut the frame line I had marked on it. I carefully make sure that the cuts are clean and without any burrs or lifts. I flip the film over and splice the back with white 35 mm splicing tape. It is only necessary to cut 26 frames of pull-up, but I have cut 2 feet, 8 frames for over 20 years. I then cut in an 8-frame piece of blank fullcoat, which I took off the end of the roll, where it is truly blank and has not been touched by a recording head. The 2 1/2’ of pull-up and 8 frames of blank equal 3’. The tail pop comes next. Now that the A-B configurations as well as the pull-ups have been built, you are ready to ship the print master to the optical house to shoot the optical master for the laboratory.

Various Formats: A Who's Who

In theatrical presentation, in addition to the 2-track analog matrixed encoded optical track, there are three basic digital formats that dominate the American theater. Dolby SR-D, SDDS, and DTS cover the majority of presentation formats. With the advent of digital stereo, the need to blow up 35 mm prints to 70 mm just to make bigger 6-track stereo presentations became unnecessary.

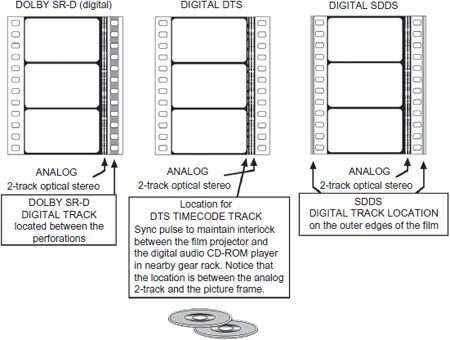

Figure 19.10 35 mm digital soundtrack formats. Dolby SR-D, digital DTS, and digital SDDS formats.

Figure 19.11 Actual image of various 35 mm digital sound formats on one print.

DTS offers an opportunity to present a multichannel stereo soundtrack to 16 mm film. The proprietary DTS timecode-style sync signal is placed on the 16 mm print, which in turns drives the outboard CD-style playback unit, much the same as its theatrical 35 mm cousin.

Figure 19.10 shows where the various audio formats reside on a 35 mm print. DTS does not have its digital track on the film; rather, it has a control track that sits just inside the optical 2-track analog track and the picture mask. This control track maintains sync between the film and a CD that plays separately in a separate piece of gear nearby. The CD has the actual audio soundtrack of the movie.

Note that the SDDS digital tracks are on either side of the 35 mm print, outside the perforations. The DTS timecode control track lies snugly between the optical analog track in the traditional mask and picture, with the Dolby SR-D digital track between the perforations.

By combining all the audio formats on the same release print, it does not matter which audio playback system a theater is using; one of the formats of sound will suit the presentation capabilities of that exhibitor.

FOREIGN M&E

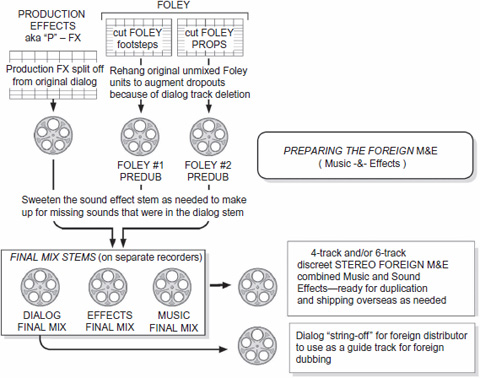

Once the print master is complete, the next step is to satisfy the foreign market. You must produce a full and complete soundtrack without any holes or sound events missing, yet also without any track of English dialog. This is mainly why each component of dialog, music, and sound effects has been carefully kept on its own roll or separate channel. However, just keeping the components separated is not enough. This is where the cautious preparation of the dialog editor (discussed in Chapter 15) pays off. If he or she has done the work properly, the mixer need only mute the dialog track and make sure that the P-FX track, which the dialog editor so carefully prepared, is open and running so those production effects may be included in the foreign M&E.

Figure 19.12 The music and effects (M&E) dubbing chart.

Preparing Foreign M&E

The mixer laces the Foley back up, as he or she may need to use more, especially footsteps and cloth movement, than was used in the final domestic mix. When the English dialog is muted, more than just flapping lips go with it. Cloth rustle, footsteps, ambience—an entire texture goes with it. The only thing remaining from the dialog track is the P-FX that were carefully protected for the foreign M&E.

We have a saying in postproduction sound. If you can get it by Munich, then your M&E track is A-Okay. The German film market is the toughest on quality control approval of M&E tracks. One of the harshest lessons a producer ever has in the education of his soundtrack preparation is when he or she does not care about guaranteeing a quality M&E. When an M&E track is bounced, with fault found in the craftsmanship, the foreign distributors must have it fixed by their own sound services, and the bill is paid by you, not them. It either comes out as a direct billing or is deducted from licensing fees.

The mixer combines the music and sound effects onto one mixed roll of film. The mixer makes a transfer of the dialog channel (called the dialog stem) as a separate roll of film so that foreign territories can produce their own dialog channel to replace the English words, if desired.

MIXING THE ACTION FILM SALT

Rerecording mixer Greg Russell, along with his colleagues Jeffrey Haboush and Scott Millan, mixed the intelligent and exciting action-film Salt at the Cary Grant Theater, on the Sony Studios lot (what used to be MGM studios).

Greg's résumé really says it all. His mixing credits include The Usual Suspects, Crimson Tide, Starship Troopers, Con Air, The Mask of Zorro, The Patriot, Spider-Man, Spider-Man 2, Pearl Harbor, Armageddon, Transformers, Memoirs of a Geisha, Apocalypto, and National Treasure. He takes a moment to tell us about the complex mix of the 2010 movie Salt, which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Sound Mixing:

My first reaction, on seeing an early cut, was, “Wow!” It's exciting, well-paced, authentic and realistic. The action is believable, and it's a solid story, really solid, with twists and turns that kept me guessing through to the end. And I loved the Salt character. Unique and clever, smart and bold. Angelina Jolie does such a great job with this role, and the film is filled front to back with incredible sound opportunities.

I mixed this film with Jeff Haboush on dialog, a mixer I've worked with on and off for nearly 27 years, and Scott Millan, a four-time Oscar winning veteran of the Bourne series, brought in to handle music. In essence, it was a return to the three-person crew that was the norm not so long ago in Hollywood. Director Phillip Noyce called the track the most complex in his career, and his vision was established clearly from the beginning.

On day one, Phillip laid out the game plan for the mix. Story and character were key, and everything we did in the soundtrack had to support her story. She is a CIA agent accused of being a Russian spy, and she's on the run trying to clear her name. So all the tension that we feel, whether it's coming from effects and high-octane car chases and bullet whiz-bys, or the group dialog with its precise, story-specific lines, or the music with its big brass and intense rhythms—we need to feel that threat she is experiencing throughout the film. He laid it out in a way that we were on the same page from the first temp dub.

Figure 19.13 Greg Russell, FX rerecording mixer, on the Cary Grant Stage.

The movie was sold by Sony Pictures using the tag, “Who is Salt?” And that's really what the movie is about. It's an investigation into the character of Evelyn A. Salt. She may be what she claims to be: an American patriot, a clandestine operative, a spy working for the CIA in foreign countries. Or she may well be what she is accused of: a Soviet-era laboratory rat bred in a secret camp in the last dark days of the KGB.

Music augments that speculation about the true nature of her character, suggesting sometimes that she is more of an American patriot than she really is, and at other times suggesting there might be a darker side to her history. The music, in a sense, is following its own script, which is sometimes on the screen and sometimes isn't.

The film is a tight 93 minutes of story, with 91 minutes of score by James Newton Howard and the music edited by longtime Noyce collaborator Joe E. Rand, delivered from his stage-side Pro Tools rig at 60 channels wide, with clear separation of orchestra elements and electronic supplements. The challenge, according to music rerecording mixer Millan, was to propel story and drive character, but never let the audience know it.

James Newton Howard and Joe E. Rand did a fantastic job. You never feel overwhelmed; you just feel subliminally engaged without ever feeling manipulated or telegraphed. Philip and James choreographed it in such a way that it plays into a perpetual sense of moving forward and keeping the tension high. The rhythm of the score as a whole was imperative. You never feel like you're stopping, or that there is a beat out of line. In this particular film, music drives the soundtrack, and that's quite unusual for an action film, where usually it's the effects that drive the sound. The reason music drives the film is because Phillip used James Newton Howard's score as the unifying factor to combine what is on the one hand fantastical, escapist popcorn entertainment, and on the other hand, a fact-based thriller—two seemingly irreconcilable genres that are pulled together and held tight by James’ score. Everything, in a sense, was subordinated to the music.

Figure 19.14 From left to right, Greg Russell handing sound effects, Jeff Haboush mixing the dialog, and Scott Millan mixing the music.

Effects and Pace

While music drives the film, the effects track, and its give-and-take with the score, keeps the pace. At times it's relentless, but it never turns bombastic. Phil Stockton and Paul Hsu, out of C5 in New York, cosupervised the film, with Hsu concentrating on sound effect design and Stockton overseeing the dialog and ADR as well as the overall delivery at the final mix.

I had never worked with them before and they delivered stellar material, sounds that put us in these very real environments. Some fantastic city sounds, and the technical wizardry of all these control rooms, the beeps and boops in the interiors. Great explosions, great vehicle sounds, and I really loved the gun work. I think people will notice that the weapons have a fat, punchy but crisp sound. You feel them in your chest without being overcooked.

At the final, Russell went out to twelve 5.1-channel hard effects predubs and four BG predubs in a 513 configuration. Meaning a L C R LS RS 1 L C R.

I do this to have better separation in the BGs; for instance, if there are insects in a scene I might put the single crickets separate on the LCR and rest of the bed of crickets on the other 5 channels. This gives me more flexibility in the final mix. This was also a huge Foley film with another 40 channels of props and 40 channels of footsteps per reel.

It's a busy movie, filled with location shoots across a lot of urban environments, hand-to-hand combat, principals on the run, and lots of crowds. There are a lot of human beings in this movie and human beings can get busy. There had to be an enormous amount of Foley to bring out the detail. Particular attention was also paid to backgrounds in this film, as the characters move constantly and the tracks serve to anchor the audience in reality. While BGs and Foley provide the glue for the effects track, in a very busy film such as Salt, it's the big sequences that the audience will remember, and there is no shortage here. Though Noyce preached from the beginning that the track always needed to be looked at in its entirety to get the complete arc of the film I loved her initial escape sequence, where she goes over an overpass to the highway. But she launches herself off an overpass, lands on a semi-truck, jumps from vehicle to vehicle while they chase her; then she crashes and is up and off on a motorcycle.

Phil [Stockton] and his team also provided an array of very cool explosions. In one particular scene, at a pretty dramatic moment in the film, we have a design-reversed sound effect that ties right into a very crisp button-click with a high-frequency ping into a huge dynamic explosion. It's a concussive impact that goes right through your body. It's a unique sound, that concussive impact, and it's one of my favorites in the movie. Then again, there are a lot of moments like that.

By all accounts, Noyce has a discerning ear and was deeply involved, down to the most minute changes, in the track. He wanted to feel a lot of sound, and he wasn't afraid to pan around the room to open up space for the audience to hear it all.

I've always believed in using sound as an “emotionator,” if I can make up a word. Noyce said to us, “No sound is innocuous, no musical note is innocuous. They simply exist. Whether it's the rustle of the wind, the sound of birds, the footsteps or the strings, they all have a dramatic and an emotional purpose within the soundtrack.”

We set out at the beginning of the sound work with a number of objectives. One was to ensure that as a ride, Salt is relentless. Once the audience gets on, we want the roller coaster to never stop. The audience has nowhere to hide, you just hold on and hope you get to the end with your brain intact. That means you are trying to create incessant rhythms of sound. There can be no pause. You're trying to hit them and hit them and hit them as if you have them against a wall, punching them. But you want them to feel as if you're just stroking them, because you want them on the edge of their seats wanting more. Every time they might want to feel like a pause, there's another sound ricocheting into the next sound, that's bouncing forward into the next one. And they keep going within a rhythm that's relentless. The trick is to find the right level, and I don't mean volume. I mean the right level of complexity without ever being bombastic.

Phillip loves the cacophony and the layers, not only in effects, but in dialog, too. Real walkie-talkies with police calls. CB radios with squelch and static. TV monitors, newscasters, people in and around the President's bunker and in CIA headquarters.

There were numerous control room interiors and a ton of outdoor scenes where we had to seamlessly blend in the ADR. But the nice thing is, he is not at all afraid to pan dialog to the right or to the left—and not just leave in the center speaker as most soundtracks are mixed. But he doesn't have us pan dialog for a cheeseball or geographical effect; he's more open up to the space so he can get important group lines or offstage lines to poke through and tell the story.

Noyce spent five months writing, casting, and recording the group dialog, as he considered every single line crucial to story. In a key scene at New York's St. Patrick's Cathedral, where the President is delivering a eulogy and all hell breaks loose, the director kept the extras on location for some special sound-only recordings, and the production sound mixer William Sarokin recorded some stellar lines for perspective and background group ‘walla’ reactions with the same level of energy that they had during the original filming, only with the real natural reverb intact—and not artificially applied by some plug-in or echo chamber.

The church scene is a real good example of how he is not afraid to move sound cues around the room. He cuts constantly to all these different angles, from security areas where they're monitoring the eulogy and the President is off to the right, then over to the rear, cut to the catacombs and you hear him reverberating through the speakers, then you pop up on the other side of the church, then you're tight up on him. And all those reverbs are panned. But with all that reverb it was never distracting. The director had us move the dialog without the audience even noticing that it was being done—a very natural three dimensional audio experience.

The group dialog track became key for Noyce because it adds that layer of verisimilitude, placing the audience believably in the center of the action. None of that, ‘Duck, he's got a gun'ism’!’ Every line had meaning. My favorite scene is really all of reel 5, when you're down in the bunker under the White House. You have professional newscasters commenting on this crazy day, coming out of monitors in a room full of people, walkie-talkies, perspective cuts in and out of the room. At one point I put this cool P.A. effect on our lead actors because they're coming out of a speaker. Then we're back in the room inside all the chaos. It's an amazing use of layers, and you hear every syllable. William did a great job with the production track, and Deborah Wallach did a great job of providing ADR that was seamless.

No doubt audiences will leave theaters feeling like they've been on a roller coaster, but the way it's been set up, they won't feel yanked around and they won't feel ear fatigue or the lingering effects of sonic bombardment.

Salt is a great ride, one of the better films I've worked on in along time. A spy thriller is right up my alley, and this is Phillip Noyce doing what he does best.

Phillip said, “This mix team could be described as ‘smooth as silk’.” I don't think I've ever had a soundtrack that was so complex and yet at first appears to be quite straightforward. I've had many tracks over the years that have cried out to the audience, ‘Listen to me!’ This track doesn't cry out ‘listen to me’ —you just find yourself sitting in the middle of an audio experience.

You don't know what is being done to you, but these sound mixers are wrapping you up and pushing you along this way and pulling you that way. But because they have mixed the interwoven cues with such subtlety, you give over to the experience. And that is truly great sound mixing—an art form that Greg Russell and his colleagues have done many times—many years.

Real veteran “know-how” cannot be taught—it takes time.