Chapter 17

Foley

The Art of Footsteps, Props, and Cloth Movement

“They had to blame the failure of the picture on something. So they

blamed it on Foley.”

In the early days of sound when the silver screen developed a set of lungs, relatively few sound effects were cut to picture. With rare exceptions, and only on major motion pictures, sound effects were cut when nothing was in the production dialog track. With each picture the studios turned out, fresh ideas of sound methods pushed steadily forward. Both audience enthusiasm and studio competition fueled the furnace of innovative approaches in sound recording and editorial, along with new inventions in theatrical presentation.

Artisans such as William Hitchcock, Sr. (All Quiet on the Western Front), Robert Wise (a director who started as a sound editor before he rose to become a picture editor for Orson Welles on Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons), Ronald Pierce, Jack Bolger, Gordon Sawyer (Sam Goldwyn's legendary sound director), Roger Heman, and Clem Portman overcame more than just new creative challenges—all also overcame the problems presented by the new technology of sound, dealing with constant changes in new equipment variations and nonstandardization.

JACK FOLEY

Even though the Warner Brothers had been producing several synchronized sound films and shorts as experimentations with Vitaphone's sound-on-disc system, it was John Barrymore's Don Juan, which premiered October 26, 1926, at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre, that thrilled the audience and positively pointed the way for audience acceptance and appeal of sound. These early films synchronized musical scores and some sound effects as they could, but the following year it was Warner Brothers’ production of The Jazz Singer that sent other studios scrambling to license, adapt, or develop systems of their own. Starting out as a stunt double in the silent era of the mid-1920s at Universal, Jack Foley soon found himself working as assistant director on several pictures filmed on location in Owens Valley and then shooting inserts and shorts back at the Universal lot. When The Jazz Singer opened at the Warner Theatre on October 6, 1927, with synchronized singing, segments of lip-sync dialog, and a story narrative, it was evident that tremendous opportunities to overcome the new challenges would present themselves.

Universal had finished making Show Boat as a silent picture just prior to the premiere of The Jazz Singer when the studio realized its picture was instantly rendered obsolete. Universal would have to find a way to retrofit it with sound before they released it.

Like so many breakthroughs in technology or procedure, the mother of invention is usually forced into a dedicated ingenuity by individuals with little choice but to do something never done before—not because they want to, but because they have to. Such was the case with people like Jack Foley. Engineers set up a rented Fox-Case sound unit interlocking the recording equipment to the projector so that the picture would be thrown onto a large screen on Stage 10. A 40-piece orchestra, under the direction of Joe Cherniavsky, would perform the music visually to the picture. In an isolated area to the side, Jack Foley and the rest of the sound effect performers also watched the projected picture as they made various sound effects, even performing crowd vocals such as laughing and cheering, as well as clapping, while the orchestra performed—a technique that became known as “direct-to-picture.” The retrofitted soundtrack worked remarkably well, and soon other silent pictures that needed sound were brought to Universal to utilize Stage 10 for similar treatment.

During the first few years of the talkies, sound effects were almost always recorded on the set along with the actors’ voices. Many scenes were not filmed using sound equipment and required direct-to-picture effects to augment them.

Soon, the advent of optical sound allowed editors to cut an ever-increasing number of sound effects, including footsteps in precise sync to the picture. Such cutting was considered a “sweetening” process, adding something that did not already exist in the production soundtrack. As the quality of the extra sound effects grew, however, it became clear that cutting in new sound effects would make a much more dramatic and pristine final sound mix than most of the production-recorded sounds. A new labor force emerged, editors dedicated only to cutting sound.

The only footsteps heard in these first sound pictures were the actual footsteps recorded on the set. By the mid-1930s, editors were cutting in footstep sound effects (also known as footfalls) from the growing new sound libraries to various sequences on an as-needed basis. The technique of cutting in new sound effects grew to the point that most sound editors commonly cut footsteps to all characters throughout the entire picture, all pulled from the studio's sound library. It became more and more difficult to find just the right kinds of sounds in the sound library to meet the growing demand to cover subtle movements and props.

Jack spent most of his time “walking” the actors’ performances over again, using the direct-to-picture technique. By now, Jack and his crew had slowly transformed a small sound stage into a full-time direct-to-picture facility (dedicated to sound effects only), with music being recorded on its own dedicated scoring stage. The film projector was synchronized to an optical film recorder (a specially built 35 mm camera adapted for photographing sound via light impulses) in the machine room as Jack stood in the middle of the sound stage floor, watching the projection screen and performing the selected actor in whatever footsteps and/or movements were made.

The recording mixer was seated behind what was referred to as a control desk (known today as a mixing console), where he or she carefully raised or lowered the volume level, sending the signal back into the machine room to the optical film recorder, watched by the recordist, who carefully monitored the sound quality that came to it.

Of course it was not possible to roll back the recording and listen to the performance for approval. Remember, these were still the days of optical sound. The sound image that had just been recorded went to the film laboratory and was developed before it could be heard. Even if it could be listened to, it could not be backed up and played. Rock-and-roll transport technology was still years in the future.

Sound craftspeople at Universal simply referred to the direct-to-sound stage as “Foley's room,” but it was when Desilu Studios built its own direct-to-sound stage facility that they officially honored Jack by naming their stage the Foley stage. The term stuck and today it is used all over the world.

In those early years many sound editors performed their own custom effect needs, but, as films became able to have customized footsteps from beginning to end, a special performer was needed to walk the entire picture, thereby guaranteeing continuity to footstep characterization and style. A few sound editors spent more time walking Foley cues for other editors, slowly evolving into full-time Foley artists.

During Jack Foley's 40-year career at Universal, he became the footstep performer of choice for movie stars on a regular basis, each of which had individual characteristics. Jack referred to Rock Hudson's footsteps as “deliberate,” James Cagney's were “clipped,” Audie Murphy's were “springy,” Marlon Brando's were “soft,” and John Saxon's were “nervous.”

Sometimes the amount of sound work to perform would be so heavy that Jack would get his prop man involved, pressing him into walking with him or performing a piece of movement while he concentrated on the primary sound. When Walter Brennan was not busy working on his own picture as an actor, he often spent time walking cues with Jack over at Universal. It was Jack who suggested Brennan put a rock in his shoe, thereby giving Brennan his famous limp.

“You can't just walk the footsteps,” recalls Joe Sikorski, a veteran sound editor of nearly 400 pictures and a colleague of Jack Foley during the 1950s. “When Jack performed a scene he got into the actor's head, becoming the character. You have to act the part, getting into the spirit of the story. It makes a big difference.”

For the epic battle sequence in Spartacus, Jack was faced with the unique and exciting challenge in the scene where 10,000 battle-hardened Roman troops pressed forward in a deliberate rhythm as they approached the ridge where Kirk Douglas and the slave army stood. After consultation with director Stanley Kubrick, and knowing that trumpet brass and heavy drums would be used in the music score, Foley hit on the idea of putting together hundreds of metal curtain rings and keys strung out on looped cords. He and his assistants stood together on the Foley stage and rhythmically shook the rings in sync to the soldier's feet, creating the extremely effective and frightening effect, uniquely underlining the military might of Rome.

Figure 17.1 Jack Foley had a love and passion for life, which was exactly the way he approached his work. A robust man with an extremely talented mind, Jack always strove to support the storytelling of the film through his “sync-to-picture” customized approach, which the world now refers to as “Foley.” Photo courtesy of the Foley Estate.

MODERN FOLEY

Alas, the last of the old studio Foley stages has been torn down and rebuilt to service the demands of modern film. Today's Foley stages have evolved into efficient and precisely engineered environments, capable of recording either in analog or digital to myriad formats, but most of them lack that really lived-in world that made great audio character.

A talented work force of specialists known as Foley artists (a.k.a. Foley walkers or steppers, now considered demeaning terms by many Foley practitioners) spend a huge portion of their lives living in these acoustical cave-like stages amid an eclectic junkyard.

These remarkable sound effects warriors immerse themselves in an amazing type of consciousness, consumed by attentive study of how people walk and move and realistic recreation of sounds that replicate a real-life auditory experience for the audience. Foley artists must create sounds with various available props on hand that are made to sound like other props that are either not on hand or don't exist to create a sound never before heard.

Figure 17.2 Director Robert Wise made a clean-room bio-suit and stainless steel security pylon available for Joe Sikorski to perform the custom sound effect “Foley cues” for the 1970 techno-thriller The Andromeda Strain. Photo courtesy of Joe Sikorski.

The most dramatic body fall impacts are also created on the Foley stage. Very few recordings in the field can equal the replication of a Foley artist. Years ago, David Carman, a humor illustrator, and his wife visited our sound facility in North Hollywood. I gave them an audio demonstration, playing the various sound effects that make the dramatic magic used to acoustically sell the action. One such effect was cue 1030-02, “Groundfalls” (found in the Yewdall FX Library, under BodyFalls on this book's accompanying DVD). As I played the series of vicious body falls, David asked how we could make such wicked-sounding impacts.

Teasing, I replied deadpan, “My Foley artist, Johnny Post, lines up all the assistants in a row, and for each take he picks them up one by one and slams them to the concrete. Kind of tough on the body—that's why we go through so many.” A couple of months later I received the following illustration that is Figure 17.3. Copies hang in many Foley stage recording booths in Los Angeles.

John Post is considered a grand old gentleman of the Foley art form. I have lost count of how many aspiring young Foley apprentices John has taken under his wing and trained. What he can do with a bowl of vegetables is truly disgusting, not to mention what he can do with an old broken camera, a leaf rake, or an old rotary phone mechanism—all to create some new high-tech prop gadget on screen.

Figure 17.3 Body fall.

Johnny Post is one of the most creative and resourceful sound men I have ever had the pleasure to work with. He could pick up an ordinary “nothing” object sitting in the corner of the room and perform sounds that you would never imagine could be made with them. I once watched him perform a couple romping on a brass bed (I leave that to your imagination) and all he used was his foot flexing a metal leaf rake on a trash can lid. He inspired us all how to creatively think—to achieve the sounds we needed with everyday things that lay around us.

Many Foley artists are former dancers, giving them the added advantage of having a natural or trained discipline for rhythm and tempo. Some Foley artists, especially in the early days, came from the ranks of sound editors, already possessing an inbred understanding of what action on the screen is needed to be covered. This background is especially valuable for those hired to walk lower-budget films, where full coverage is not possible. Both the supervising sound editor and the Foley artist must understand and agree on what action to cover and what action to sacrifice when there just isn't sufficient time to physically perform everything.

It is not enough to know that Foley artists perform their craft in specially engineered recording studios outfitted with pits and surfaces. Whether one is a supervising sound editor, Foley supervisor, or freelance Foley artist, traveling to the various Foley stage facilities and researching them carefully are valuable experiences. I have taken many walk-through tours with facility executives anxious to expose their studio services to potential clients. Most of these tours were extremely shallow, since most of those who tour a Foley stage really do not understand the true art form in the first place. They usually consisted of walking into a studio with the executive giving a cursory gesture while using the latest technological buzzwords and always reciting the productions that just used their stages. When I got back to my shop, I always felt like I had heard a great deal of publicity but really came away with little more substance than before I arrived.

Taking a tour is an extremely important beginning, especially for understanding the capabilities of the sound facility and for building a political and/or business relationship with executive management. Ask for a facility credit list, handy during meetings with your client (producer). Discuss the pictures or projects each stage has done. Find out what Foley artists have used the facility recently. Talk to these artists about their experience on the stage in which you are interested, and, if possible, hear a playback of their work. This gives a good idea of the kinds of results you can expect.

Look the credit list over thoroughly. Serious facilities are very careful to split out credits into the various services they offer, taking great care not to take undue credit for certain services on pictures that are not theirs. For instance, I noticed that one facility listed a picture in such a way as to give the impression that they had handled the Foley, ADR, and the rerecording mixing. I knew for a fact that another studio had actually performed the final rerecording mixing, and so I inquired about that accreditation. The facility executive was caught off-guard, quickly explaining that they had only contracted the Foley stage work. I nodded with understanding as I commented that he might redo the credit list and split the work out accordingly in the future. It may seem superficial and unimportant while reading this, but a precise and verifiable credit list is an important first impression for those deciding which sound facility to contract. If one item on the credit list of your career résumé can be called into correction when a potential client checks you out, it can cast doubt over your entire résumé.

Once you have had the facility tour and collected all the available printed information from the facility (including their latest rate card), politely ask if it would be all right to visit the stage on your own, both when a Foley session is in progress and when the stage is “dark” (meaning not working). This way, at your own leisure, you can walk around the Foley pits, study the acoustics, and visit the prop room.

IT'S REALLY THE PITS

You always can tell if a Foley stage was designed by an architect or by a Foley artist. Most architects do not have adequate experience or understanding in what Foley artists want or need, and, more often than not, they only research the cursory needs of the recording engineers and acoustical engineering. These are vital needs. Not addressing them properly is facility suicide, but many Foley artists are distressed that so few facilities have consulted them prior to construction, since the stage is their workplace.

Most of the Foley stages I have worked with over the years had to undergo one or more retrofittings after discovering their original design did not accommodate the Foley artists’ natural workflow or was not isolated enough from noise for modern sensitive digital technologies. They rebuilt the pits, changed the order of surface assignments, and grounded the concrete to solid earth. This last issue is of extreme importance, as it dictates whether your concrete surface actually sounds like solid concrete. Oddly enough, most Foley stages suffer from a hollow-sounding concrete surface because they are not solidly connected to the ground.

Figure 17.4 The “pits” of a typical small Foley stage. The Foley artist stands in these variously surfaced pits, performing footsteps in sync with the actors while they watch them onscreen. Most Foley stages are equipped with both film and video projection. Photo by David Yewdall.

When I contract for a new job, I run the picture with the producer, director, and picture editor with at least a cursory overview. I have learned consciously to notice how much concrete surface work I must deal with in Foley. If the picture is a western, it doesn't matter. If the picture is a science-fiction space opera, it doesn't matter. However, if the picture is a police drama or gangster film, concrete surfaces abound. Mentally I strike from consideration the Foley stages that I know have hollow-sounding concrete surfaces, because it will never sound right when we mix the final soundtrack.

Back in the mid-1980s I did a Christmas movie-of-the-week for a major studio. Part of the agreement was to use the studio's sound facilities. Since it was my first sound job using its stages, the sound director decided to visit me on the Foley stage to see how things were going. He asked me how I liked it. I told him, not very much. He recoiled in shock and asked why. I pointed out through the recording booth windows that the concrete sounded hollow. He charged through the soundproof access door and walked out onto the concrete surface, pacing back and forth. What was the matter with it? It sounded fine to him. I told the sound director that it did not do any good to try to assess the quality of the concrete surface out there; he had to stand back with us in the recording booth and listen through the monitor speakers as the Foley artist performed the footsteps. The sound director stood out on the floor defiantly and asked what good that would do. I explained it made all the difference in the world—what you hear with your ears is not necessarily what the microphone hears.

The sound director came back to the recording booth, and I asked my Foley artist, Joan Rowe, to walk around on the concrete surface. The sound director stood there in shock as he heard how hollow and unnatural it sounded. He turned to his mixer and demanded why he had not been told about this problem before. The mixer replied that they had complained on numerous occasions, but that perhaps it took an off-the-lot client to get the front office to pay attention and do something about it. A couple of months later I was told that a construction team was over at the studio, jackhammering the floor out and extending the foundation deep into the earth itself.

When you return to revisit the Foley stage facility you are considering, walk around on it by yourself, and take the time to write detailed notes. Draw a layout map of the pits. It is crucial to know which pits are adjacent to each other, as it makes a difference in how you program your show for Foley cues. If you are doing a western and the hollow wood boardwalk pit is not next to the dirt pit, there will be no continuous cue for the character as he steps out of the saloon doors, crosses to the edge of the boardwalk, and steps off into the street to mount his horse. To cue such action in one fluid move, the Foley artist must be able to step directly from the hollow wood surface pit into the dirt pit. Now you begin to see the need for a well-thought-through Foley pit layout.

Note the surface of each pit. Sketch the hard surface floors that surround the pits and make a note of each one's type. You should have bare concrete (connected to solid earth), a hardwood floor, linoleum and/or tile, hard carpet, and marble at the very least. The better Foley stages have even more variations, including flagstone patio surface, brick, and variations of carpet, marble, hardwood, and others.

One of the first surfaces I always look for is a strip of asphalt—real asphalt! A well-thought-out Foley stage floor has a long strip, at least 10’ to 12’ long by approximately 2’ wide, of solidly embedded concrete, with a same size strip of asphalt alongside it. It is annoying when concrete is made to sound like asphalt because no asphalt strip is available for onstage use. These kinds of subtle substitutes really make a Foley track jump off the screen and say, “Hey, this does not connect!”

If viewers are distracted enough to realize that certain sounds are obviously Foley, then the Foley crew has failed. Foley, like any other sound process in the final rerecording mix, should be a seamless art form.

The other important built-in is the water pit. No two stages have the same facilities when it comes to water. Before the advent of decent water pits, water almost always was cut in hard effects from the studio's sound effects library. On shows that needed more customized detailing, Foley artists brought in various tubs and children's blow-up vinyl pools. The problem with these techniques, of course, is that the Foley artist and recording mixer must constantly listen for vinyl rubs or unnatural water slaps that do not match the picture. Not only does this dramatically slow down the work, but not enough sensation of depth and mass of water can be obtained to simulate anything more than splashing or shallows.

Only big pictures with substantial sound budgets could afford to pay for a major 4’ deep portable pool to be set up on the Foley stage, as was done on Goldwyn's Foley stage for the film Golden Seal. Naturally, a major commitment was made to the Foley budget while the stage was tied up with this pool in place (at least a 15’ diameter commitment to floor space was necessary for weeks). A professional construction team set it up with extra attention to heavy-duty bracing to avoid a catastrophic accident should the pool break and flood the sound facility floors.

Today, almost all major Foley stages have variations of a water pit. Water pits should be built flush to the floor and extend down into the earth three and a half feet. The audio engineer told me that the concrete foundation went several feet deeper, ensuring a solid grounding with the earth for all the pits and floor surfaces.

Figure 17.5 This is a combination of doing metal sound effects underwater by using a water pit. Notice how the Foley artists use various fabric or packing blankets wrapped over the flat tile surfaces to defeat the unwanted “slappy” effects that bare tile would yield. In this case the crew does not have an underwater microphone so they have to slide two prophylactics, one over the other then tightly taped up near the XLR connector, and carefully submerge the mic under the water up near, but not above, the top of the prophylactic protection. Photo by David Yewdall.

Invariably, almost all Foley stages with permanently built water pits suffer from the same problem: precise attention was not paid to the slope and surface of the edges of the water pit. Although these pits are deep and can hold enough water to adequately duplicate mass and heft of water for almost any Foley cue, they still suffer the “slap” effect at the top edges. I have yet to see a water pit with a sloped textured edge.

If your project has hollow wood floor needs, check the hollow wood floor boardwalk pit. I do not know why, but several Foley stages use 2’ × 4’ wood planks. This size is far too thick to get a desired hollow resonance. Make sure that the boardwalk pit uses 1’ × 4’ nonhardwood planks, such as common pinewood. Walk on it slowly, listen to each plank, and test each edge. Foley artists often get a hammer and adjust these planks so that one or more of them has loose nails, allowing the artist to deliberately work loose-nail creaks into the performance if appropriate. This technique works well when a character is poking around an old abandoned house or going up rickety stairs. It is vital to be able to control just how much nail creak you work into the track; a little goes a long way.

Many stages have at least one metal deck, and, by laying other materials on top of it or placing the microphone lower to the floor or underneath it, you add a wide variety of textures. Roger Corman's Battle Beyond the Stars was an action-adventure space opera with various spaceships and futuristic sets. The entire picture had been filmed in Venice, California, in his renowned lumberyard facility, and the spaceship interiors were crossbreeds of plywood, cardboard, Styrofoam, and milk crates, none of which sounded like metal at all. We knew we would walk the Foley at Ryder Sound's Stage 4, which had a smooth metal deck set flush to the concrete floor as well as a very nice roll-around metal ladder.

I knew, however, we would need much more than that. Contacting Bob Kizer, the picture editor (yes, the same R.J. “Bob” Kizer we spoke about in the last chapter; he was a picture editor before he evolved into a world-class ADR supervisor), I advised him of the problem. “Could you ask Roger to cough up an additional $50 so I could have something made to order?”

The next day, cash in hand, I dropped by the nearest welding shop and sketched out a 3’ × 2’ metal diamond deck contraption with angle iron underneath to support human weight. The deck was to sit on four 6” high steel tube legs, solidly welded in place so the microphone could be positioned under the diamond deck for an entirely different kind of metal sound as desired. Listen to cue #43 on this book's accompanying DVD to hear two examples of metal sounds.

By positioning this deck platform onto the concrete floor or onto the existing smooth metal deck of the stage, we could achieve numerous characterizations of the metal footsteps. We pulled a 3’ section of chain-link fence out of the prop room and laid it over the diamond deck for an even stranger type of spaceship deck quality. For years that metal diamond deck has been floating around town from one Foley stage to another. Every time I needed it, an “all points bulletin” had to be sent out, as I never had any idea who had it at any given time.

Listen to the sound cue on the DVD provided with this book of “Various Foley Footstep Cues” performed on various types of described surfaces, found in the Paul JYRÄLÄ library, Footsteps various.

Figure 17.6 For Battle Beyond the Stars, I had a steel diamond deck prepared with 6” steel pipe legs. Recording microphones could be used under as well as above the deck for an entirely different sound. For this cue, a chain-link fence gate was laid atop the diamond deck to make the “mushy” metal surfaces to Camen's ship. The bottom photo shows a Foley artist team putting together several types of metal textures to create a very particular metal cue. Photo by David Yewdall.

PROP ROOM

Another important place to search when checking out a Foley stage is the prop room. You can always tell the amount of professionalism and forethought given the building of a Foley stage by whether a real prop room was designed into the facility. If a stage has a prop room that is just a closet down the hall, work progress slows down, costing hundreds of dollars in additional hours taken by the Foley artist repeatedly leaving the stage to access the prop room and storage areas.

The prop room should be directly accessible to the stage itself and large enough to amass a full and continuous collection of props (basically useless junk that makes neat sounds). This “junk” needs to be organized and departmentalized to accommodate easy acquisition. Everyone greatly underestimates an adequately sized room. Only a Foley artist can advise an architect how to design a proper prop room, complete with appropriate shelving, small prop drawers, and bins for storage. Smart sound facilities will not only have a convenient and adequately sized prop room, but will actively collect various props for it. You never complete this task. Every project will have its own requirements and challenges.

Figure 17.7 The prop resources at the Foley stage at 20th Century Fox are immense; they have to be. Photo by John LeBlanc.

One major studio had employed a sound man by the name of Jimmy MacDonald. Over the course of 35 years Jimmy had custom-made several thousand devices and props for the studio's Foley stage. He was literally the backbone for the studio's reputation for unique sounds as custom performed for their famous cartoons and animated features. Over the decades Jimmy's masterful craftsmanship continued to make these ingenious and valuable tools of the sound creation trade. Studio carpenters built a wall with hundreds of various sized drawers with identification tags so efficient and detailed that each prop or group of similar devices could be carefully stored and protected for years of service, allowing quick access by a Foley artist without spending valuable time hunting through the entire prop department looking for what is needed.

In the mid-1980s, when the studio was wavering about whether or not to shut down their aging sound facility or spend millions to redevelop it, they brought in a young man to head the sound department and infuse new blood and new thinking. With hardly any practical experience in the disciplines and art form of sound, the new department head walked through the studio's aging Foley stage to recommend changes. All he saw was a huge room filled with junk. He ordered the place cleaned up, which meant throwing out nearly a thousand of Jimmy MacDonald's valuable sound props. Some were salvaged by quick-thinking Foley artists and mixers who knew their value, some were sent to Florida for an exhibit, but many were lost due to ignorance. The great sadness is that, with that unfortunate action, a large part of a man's life and contribution to the motion picture industry was swept away. It is difficult to say for how many more decades Jimmy's devices would have been creating magic. If the young department head only had called a meeting of respected professional Foley artists and recording mixers for advice on assessment, reconstruction, and policy, the industry would still have the entire collection of Jimmy's sound effect devices.

Figure 17.8 Bottles, dishes, utensils, pots, and pans of all variations, historic periods, and types. Photo by John LeBlanc.

Numerous excellent props have been painstakingly collected over the years from old radio studios by several Foley facilities specially built for making custom sound effects in the days of live broadcasts. One of my favorite sounds that is very hard to record in the atmospheric bedlam of the real world is the classic rusty spring of a screen door. Austin Beck, owner of Audio Effects and veteran of the days of live radio, acquired numerous props from an NBC radio studio, including half-scale doors, sliding wood windows, and thick metal hatches mounted on roll-around platforms. The metal spring in the screen door had been allowed to properly rust and age for years and was used to customize the most unbelievable sounds.

In the final shoot-out scene in Carl Franklin's film One False Move, Michael Beach (Pluto), mortally wounded by Bill Paxton in an exchange of gunfire, staggers out the back screen door and collapses to the ground in a slow, dramatic death scene. All the country insects and birds had quieted, reacting to the sudden outburst of gunfire. Music did not intrude; no one spoke; the moment was still, electrified with the energy and shock of the moment. The screen door slowly swung back and gently bumped closed. No one would ever suspect that it was anything but production track, but it was not. It was Austin Beck's NBC half-pint screen door prop.

Figure 17.9 Various locks and deadbolts mounted on a practical door give the right resonance and make it quick and easy for a Foley artist to perform such sounds. Photo by John LeBlanc.

Foley artists appreciate a well-equipped prop room; although they are known to cart around boxes and suitcases of their own shoes and favorite props, they always want to know that they are working in a facility able to supplement their own props with a collection of prop odds-and-ends on stage. A Foley artist's boxes of props are the arsenal of tools that achieve countless sound effects. With so many modern films using pistols and automatic firearms, a Foley artist needs a variety of empty shell casings at the ready. Some artists keep a container filled with a dozen or so .45 or 9 mm brass shell casings, a dozen or so magnum .44 shell casings, and a dozen or so 30-06 or .308 shell casings. With these basic variants, a Foley artist can handle shell-casing drops as well as single shots or automatic ejection clatters for any type of gunfight thrown their way.

Every Foley artist looks like a shoe salesman from skid row. The shoes in their boxes do not look nice and new. Most look as if the Foley artist had plucked them off street urchins themselves. These shoes are usually taped over to lessen squeaky soles; they have been squashed and folded over, and any semblance of polish has been gone for years. If Foley artists do not have at least 10 pairs of shoes in their bags of goodies, they are not serious enough about their work. They should be able to take one look at a character and, regardless of the shoes worn, reach into their boxes to pluck out just the right pair for the job.

Figure 17.10 You are going to need a lot of shoes: all types of soles, all types of characters. Photo by John LeBlanc.

Figure 17.11 Lead Foley artist Dan O'Connell works with his favorite bolt-action prop rifle, specially loosened and taped up to maximize the desired weapon movement jiggles. Dan also carries a belt of empty .50 caliber brass shell casings and nylon straps to recreate gear movement. Photo by David Yewdall.

We attached sponges to the bottom of John Post's shoes so he would sound like squishy-footed mutants in Deathsport. The steel plates wrapped with medical tape on the bottoms of the motorcycle boots worn by Joan Rowe added a certain lethality to Dolph Lundgren in The Punisher.

Lead Foley artist Dan O'Connell understands the world of audio illusion. From conceptual detailing for feature projects such as Mouse Hunt, Total Recall, Star Trek II, III, and IV, and Dune, to heavy-duty action pictures such as The Rock, Cliffhanger, Con Air, and Armageddon, to historical pieces such as Glory, The Last of the Mohicans, or Dances with Wolves, Dan O'Connell has developed a powerful and respected résumé for handling comedy, to fantasy, to heavy drama. In his studio in North Hollywood (One Step Up, Inc.), Dan and his associates revel in developing that sound that directors and producers always ask for—something that the viewing audience has never heard before. O'Connell explains:

You have to have a passion about your work. Without passion you are just making so much noise to fill the soundtrack, instead of developing the story point with just the right nuance. We assist the director in telling his story in ways that he and the actors cannot. Try distilling the in-the-pit-of-your-stomach terror of an unseen spirit that is flexing the bedroom door of your bedroom through a spoken narrative. What's the actor going to do, sit up in bed and say, “Gee, I'm terrified?” He or she is so scared they can't talk—are you kidding? We make the audience experience the terror along with the frightened actor through created sound inventions—that's what we do.

SUPERVISING FOLEY EDITOR

If the project is big enough and a supervising sound editor has the budget, a supervising Foley editor may be hired to oversee all Foley requirements.

The Foley supervisor sits down and runs the picture with the supervising sound editor, spotting and discussing specific cues that must be addressed. Then the Foley supervisor programs the entire show for both footsteps and props. When I am contracting a show to supervise, I will personally go to the stage to work with the Foley artists and mixer to establish the surfaces and props for that particular movie, but I do not sit around and watch every single cue being done.

If I cannot afford a dedicated Foley supervisor, I would rather let the professional lead Foley artist work as a team with his or her second Foley artist and Foley mixer to expedite the work and not slow down the process with excessive presence.

If the movie has special sound effect challenges that require a cue-by-cue decision and finesse, of course, I will stay and work with them to help develop and perform the right sounds. I do go to the Foley stage when they call and tell me that they are ready to play the reel for me. I'll review the work in a playback with them and point out the changes that I want.

I am very particular about surface texture. If I don't like how the character of the surface is playing, I'll have them redo it. Most of the time, I have already had a thorough briefing with the Foley mixer and Foley artists, so we have already gone over those kinds of issues. My lead Foley artist will demonstrate his or her intent for the various characters and surface textures that I have listed in the cue sheets, so before I return to the cutting room we all know exactly what is going to work and what doesn't. If I need to sit on the stage and oversee my Foley artists perform each and every cue then we hired the wrong crew.

I had this backfire on me once, however. I was completing the final rerecording mix of Dreamscape over at another studio and I had to start my Foley artist crew on night sessions on John Carpenter's car thriller Christine. It was a very busy season that year, and the Foley stage at Goldwyn Studios was booked up. The only way we could squeeze in Foley sessions was to schedule them at night. I asked my lead Foley artist, John Post, if night sessions would be acceptable. He said yes.

The evening of the first session, I was still tied up with other matters back at the cutting room and could not shake free. John had helmed most of my important projects before, so I felt very comfortable with him starting on his own, even though he had never screened any of the film prior to the Foley session. Why should I worry? After all, I had Charlene Richards, one of the best Foley mixers in the business, handling the console. Several hours later, I called to see how things were going. Charlene informed me everything was fine, aside from the fact that the cue sheets did not match anything, but not to worry, as they were rewriting them as they went. I was not immediately suspicious with that disclaimer, but asked if I could speak to John Post. Charlene patched me straight onto the stage to speak to John, who welcomed a break to catch his breath.

John told me not to worry, everything was going fine, but, wow, there certainly was a lot of action in this movie. John asked if I had all those fancy helicopters in my sound library. My thought process skipped a groove. Helicopters? I asked him what he saw on the screen. John said he had never seen helicopters fly between and around buildings like that. I did not waste a moment. “Put me through to the projectionist.”

When the projectionist answered the phone, I told him to look at the film rack and tell me what he saw. A loud unpleasant exclamation burst forth. The daytime Foley sessions had been working on Blue Thunder. The projectionist had picked up and mounted reel 1 of the wrong film, and John Post had been busy creating worthless Foley cues for 3 hours!

Back then we did not have any head or tail titles for a film until well into the final rerecording phase of the mix. The only way to tell one show from another was by paying strict attention to the handwritten labels on the ends of the film leaders themselves, which obviously that projectionist had failed to do.

EMPHASIS ON FOLEY CREATION

Charles L. “Chuck” Campbell received his first theatrical screen credit on a 1971 motion picture docu-feature entitled The Hellstrom Chronicles. He describes the project:

It was an amazing project to work on. Much of the picture was shot with macro-lenses, so we, the audience, are watching the insect versus mankind sequences on their level. We had to come up with all sorts of sounds that did not exist or would be virtually impossible to record, like insect leg movements, time-lapse photography of plants growing, opening in daylight, closing at night. I spent hours on the Foley stage to oversee and help make the kinds of sounds that we knew we would need.

Campbell supervised the sound editing on two of Robert Zemeckis's early films, I Wanna Hold Your Hand and Used Cars, which attracted the attention of Steven Spielberg. Spielberg was impressed with the detailing that Chuck brought to those films and in turn, asked him to supervise the sound editorial chores on E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial.

Needless to say, it was a huge break for me. As is my style, I put major emphasis on creating much of the sound effect design on the Foley stage. I personally oversee it so that I can have immediate input and help the Foley artists focus on achieving the necessary sound cues.

Campbell's attention to detail and almost fanatical use of the Foley stage and its artists helped redefine for many of his peers the importance of Foley. Many rerecording mixers were using Foley as simply a filler (many still consider it such); if the production track or the cut hard effects were not making the action work, only then would they reach for the Foley pots. Rather than using Foley as a last resort, Campbell shoved his Foley work into a dominant position.

I approach the creation of each sound effect from a storyteller's point-of-view. What is the meaning, the important piece of action that is going on? The sound must support the action, or it is inappropriate. That is one of the big reasons that I create the sound cues that I want in Foley. If I have them in Foley, why would I waste time and valuable editorial resources recutting them from a sound effect library? I just customized them exactly as I want them for that piece of action for that film.

Figure 17.12 The lead Foley artist studies a sequence just prior to performing the cue on the Foley stage at 20th Century Fox.

This philosophy and technique served him and his partner, Lou Edemann, well. Campbell won the Academy Award for Best Sound Effects Editing three times (E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Back to the Future, and Who Framed Roger Rabbit?) as well as the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for Best Sound Editing for Empire of the Sun. In recent years, Charles has served as supervising sound editor on Catch Me If You Can and The Terminal.

SELECTION OF LEAD FOLEY ARTIST

It usually falls to the supervising sound editor to hire Foley artists. If the supervising sound editor has a dedicated Foley supervisor onboard, then it would be wise to include the supervising Foley editor in the decision-making process of hiring the lead Foley artist.

If you are responsible for selecting the lead Foley artist, two issues will guide you in the proper selection. The first one is simple: first know your scheduled Foley dates (actual days booked at a particular facility for recording the Foley performances to picture). This narrows the selection of Foley artists at your disposal because many of them already may have booked Foley commitments. The second issue is the strengths and weaknesses of the various Foley artists available for your sessions. Some Foley artists are extremely good with footsteps. They may have a real talent for characterization and texture, having less difficulty with nonrhythmic syncopated footsteps such as steeplechase sequences, jumping, dodging, or stutter-steps. If you are forced to do a walk-and-hang (often referred to sarcastically as “hang-and-pray”) Foley job, hire a Foley artist with a strong reputation for being able to walk footsteps in precise sync. (I discuss the pros and cons of the walk-and-hang technique later in this chapter.)

Some Foley artists are known for their creative abilities with props, especially in making surrogate sounds for objects either too big and awkward to get into a Foley stage or not at the immediate disposal of the Foley artist. Rarely do you find a Foley artist skilled at both props and footsteps, and those who are are seldom available because of such high demand.

TELEVISION BREAKS THE SOUND BARRIER

Until a few years ago, television sound was not taken very seriously. Most rerecording stages that mixed television series or movies-of-the-week kept a small pair of stereo speakers on the overbridge of the mixing console so they could do a “simulated” TV playback of the soundtrack. This way, they would be confident that the audio material would play through the little “tin” speakers of the home set.

Sound editors and Foley artists were looked upon in a feature versus television caste system and often were deemed incapable of handling feature standard work if they worked on too much TV. I was one of those employers who glanced over résumés and made snap judgments based on seeing too much episodic television. Shame on me, and shame on those who still practice this artistic bigotry.

Since the early 1980s, home televisions have evolved into home entertainment centers as consumers became very discerning and more audio aware. Major home theatre-style setups, once erected only by the audio/visual enthusiasts with expert knowledge of how to build their own home systems, are now within instant reach of anyone with enough cash for a ready-made system. Major electronics stores have hit teams that sell you the kitchen-sink system, and another team moves it to your residence and sets it up. Consumer awareness and desire to have such prowess in the home are added to the fact that we are now able to produce soundtracks with as great, and in some cases greater, dynamics and vitality than those produced for your local cinema.

Donald Flick, the sound editor who cut the launch sequence of Apollo 13, believed that the film sounded bigger and better in my home, played from a DVD through my customized system, than he remembered it sounding in the theater. What does this mean for today's television producers or directors? The television show or direct-to-video movie has just grown a pair of lungs and insists that you think theatrical in audio standards. Never again should the flippant excuse be used, “It's good enough for television.”

Along with this new attitude has cropped up an entire new cadre of television sound artisans, not only regarding program content but also challenging and continually excelling in its medium's format. One such Foley artist who has done sensationally well in television is Casey Crabtree. Casey has specialized in creating Foley for television, both episodic such as ER, Smallville, Brimstone, and Third Rock from the Sun, as well as movies-of-the-weeks and miniseries such as Amelia Earhart, Peter the Great, It, Ellis Island, Keys to Tulsa, Police Academy, and Bad Lieutenant, to name a few, and feature films such as Coronado, Thank Heaven, and Dancing at the Blue Iguana. Casey shares her recollections of some of those projects:

With today's compressed schedules, editors rely on Foley more and more. I create absolutely anything. I have created car crashes, sword fights, lumbering tanks crushing through the battlefield, I even created an entire 10-story building collapsing, on the Foley stage. I am particularly proud of my horses. I create horse hooves and movements that are so real the editors want me to do all of it on the Foley stage because it sounds better than any effects that they could cut by hand.

For hospital emergency room sounds I do absolutely everything. I have my own prop “crash cart” with all the devices and good-sounding junk that I used to recreate virtually everything from squirting blood vessels to syringes to rebreathers to blood pressure wraps. I even did the pocket pager beeps.

I must admit I took Casey's horse statement as being a little too self-assured, since I have been cutting horse hooves longer than I would like to recount. Casey grinned as she detected my skepticism. She proudly had her crew pull a Foley session reel from an episode of Bruce Campbell's The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. I was impressed. Her horses sounded so natural and real—hooves, texture of the ground, saddle movement, bridle jingles—as good as anything I would want for a feature film, and this was episodic television.

Figure 17.13 Casey Crabtree performs an ambu bag as an onscreen medical technician struggles to maintain life support of a patient for the hit television series ER.

Although Casey performs her craft on any Foley stage the producer requests, she is quick to point out that every stage has its own voice:

You can do the same kind of action on four different Foley stages, and you will get four different audio characterizations and colorations. Of course, I have my favorite Foley stages as well as my favorite Foley mixers, and I will discuss the options with the client accordingly. Ultimately, it is their decision where their facility deal is going to be, and I will abide by that.

I had done several episodes of one particular television show over at one Foley facility, and then the producer switched to another Foley stage for one reason or another. They got the material to the stage and did not like how it sounded—not my performance, but the characterization and color of how my performance was reproduced through the microphones of the Foley stage. There is an acoustical imprint or influence that a stage itself has. You have to factor that knowledge into the equation as well.

OBSERVING THE FOLEY STAGE IN ACTION

Visit the Foley stage when it is working. Unless the stage is closed because of a film's sensitivity, most Foley stages do not mind visitation from qualified professionals (or serious students of sound) for observation purposes. You learn virtually everything you want to know about the stage by quietly watching the recording mixer and artists at work. Watch how the mixer pays attention to the recording levels and the critical placement of the microphones. Although today's Foley artists adjust the microphone positioning themselves (except on special occasions), the recording mixer should be very attentive to how each cue sounds. If the mixer is not willing to jump up and run in to readjust the microphone stand, then that should be a red flag to his or her commitment to quality.

Observe how mixer and Foley artist work together. Are they working as a team or as separate individuals just making their way through the session? The respect and professional dedication a mixer has for the Foley artist are of paramount importance. The Foley artist could be working as hard as possible, trying to add all kinds of character to the cue, but if the mixer is not applying at least an equal dedication to what the Foley artist is doing, the cue will sound bland and flat.

Watch the mixer carefully and observe the routine. Is the mixer taking notes on the Foley cue sheet supplied by the Foley supervising editor? Is the mixer exercising common sense and flexibility as changes arise or if the Foley artist requests them?

Do not be afraid to ask the mixer questions about particular preferences. Most mixers have different priorities regarding your cue sheets and notes that make their jobs more efficient. Listen to what the mixer says; if you do decide to use this particular Foley stage, and if this mixer will be on your show, take his or her advice and factor it into your preparation.

The worst thing you can do is not work with and/or collaborate with a mixer. If a mixer feels that he or she is being forced to effect a particular style or procedure without good reason, the Foley stage experience can be very painful. To get the collaboration of the mixer, explain the shortcomings and budgetary realities and constraints you are facing, and you will get a sympathetic ear. Encourage the mixer and lead Foley artist to suggest where you might cut corners. They are sources of good advice and pointers on joining forces to accomplish your job within constraints.

Pay attention to the quality of the sound recording. Does it sound harsh and edgy or full and lush? Ask for explanations if you are unsure. Embrace the professionals you have hired and pull from their mental knowledge to enhance each cue and each track to augment the audio that you want. It will help you better understand what you need to ask to get you what you want.

A big problem that the smaller Foley stages may have is inadequate acoustical engineering. Many times a recording mixer needs to go to the thermostat and turn off the air conditioner because the microphones are picking up too much low-end rumble. This is a sure sign of poorly designed bass trapping (special acoustical engineering to isolate and vastly diminish the low-end rumble) in the air ducts that feed the stage itself. Other low-end problems arise from insufficient isolation from nearby street traffic or overhead aircraft. The Foley crew and I have had to wait on many occasions for a passing jet or a heavy tractor-trailer because the stage walls or ground foundation were not properly isolated during construction.

A few years ago, this was not such a problem. The standard microphone was a directional Sennheiser, and the recording levels were meant to be recorded as close to final intended level requirements as possible. In 1980, +6 dB recording was adopted for the Foley sessions on The Thing. By recording the Foley at a higher level (+ 6 dB) and then lowering it later in the final mix, the combined bias hiss of all the Foley channels being played back together was remarkably reduced, making for a much cleaner-sounding final rerecording mix. With the success of this elevated recording technique on The Thing, it instantly became an industry standard.

Digital technologies have accelerated the performance demands of today's Foley stages. Many stages abandoned the traditional Sennheisers for more sensitive and fuller-sounding microphones, such as Neumann, AKG, and Schoeps. These sensitive and ultra-clean microphones uncover hosts of flaws in acoustical engineering and construction shortcomings no matter whether the stages were built for the express use of Foley/ADR recording or not. If not positioned correctly, they literally pick up the heartbeat of a Foley artist. While doing the sound for Once Upon a Forest, an animal handler brought in several birds of prey so we could record wild tracks of wing flaps and bird vocals. The handler held the feet of a turkey buzzard and lifted the bird gently upward, fooling it into thinking it needed to fly. The giant six-foot wingspan spread and gave wonderful single flaps. After doing this routine several times, both bird and handler were tired and paused a moment to rest. The microphone picked up fast heartbeats as heard down the throat of the bird itself!

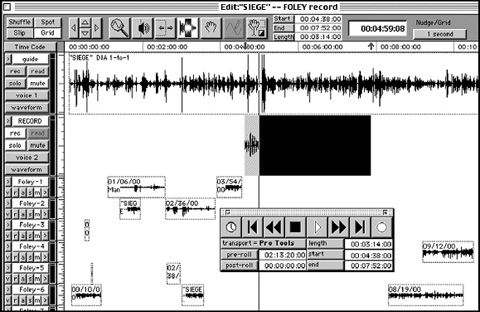

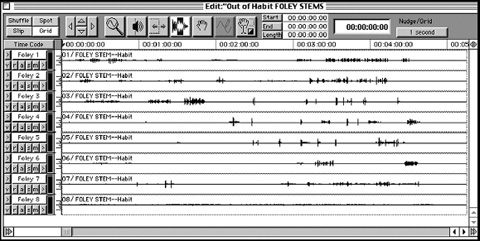

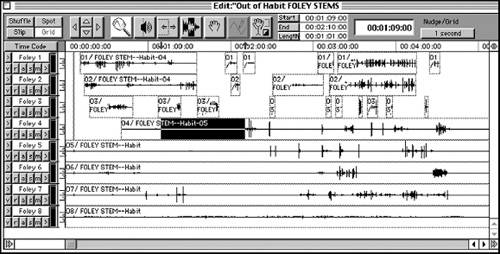

Make sure you step back into the machine room and take careful note of the various types of recording and signal processing equipment. Most Foley stages can record to various mediums, but the recording platform of choice is Pro Tools.

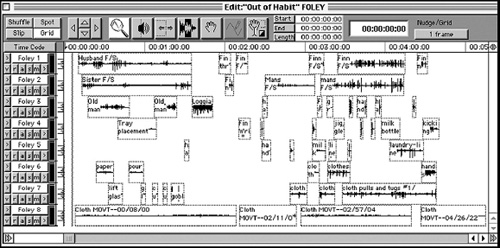

We use QuickTime video picture as it is much easier to scrub the image back and forth over the cue to determine exact sync. A great benefit of nonlinear digital editing is that now all Foley tracks can be heard playing against one another at the same time during playback of cut sequences; much better than in the days when we could only record to a 4-track 35 mm fullcoat!

Figure 17.14 Supervising Foley editor/Foley artist Vanessa Ament discusses the strategies of what they need to create with her Foley mixer, Karin Roulo (on the left), who is handling the recording session on action-thriller Chain Reaction. Sandy Garcia is the Foley recordist (in back on the right). Photo by David Yewdall.

Most Foley stages have a recordist working with the recording mixer. The recordist works all day with high-quality headsets over both ears. While loading the recording machine, he or she makes labels, keeps notes, and alerts the recording mixer if any dropouts, static, or distortion are heard from the playback head. In addition, the recordist also handles machine malfunctions, fields incoming phone calls, and alerts the mixer if the session is in jeopardy of running into meal penalties or overtime. The recordist's responsibility also includes proper setup and monitoring of the signal-processing equipment, such as Dolby SR noise reduction cards when and if they are needed.

The recordist also ensures that precise line-up tones (at least 30 seconds) are laid down at the head of each roll of stock. When a roll is completed, the recordist makes sure that it either goes to the transfer department with clear and precise notes on making the transfers or to another audio medium or burning the session folder and audio files onto a CD-R or DVD-R for the Foley editors to take back to editorial to make precise sync adjustments later.

Some Foley stages have the recordist regenerating new cue sheets to reflect what is actually being recorded and onto which channel. This practice is based on sloppy Foley cueing done by inexperienced editors who do not understand Foley protocol and procedure. Unfortunately, this extra work diverts the energies and attentions of the recordist away from the primary job of monitoring quality control as outlined above.

CUEING THE FOLEY

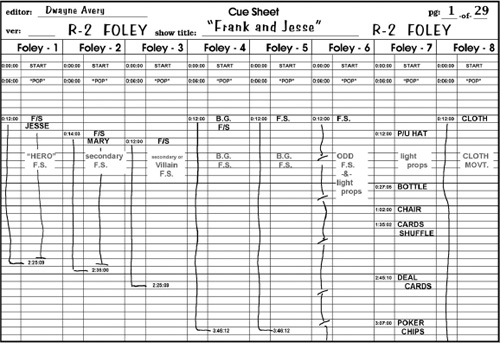

The best way to cue Foley is to pull out the trusty 8-channel cue sheets and write it up by hand. Print neatly! Remember, too, your recording mixer must be able to read this cue sheet in dim light, so do not use pencil.

Foley Cue Sheet Log

The cue sheet is not meant to go to the dubbing stage later; it is simply a road map of intent and layout by which the recording mixer navigates. As the recording mixer executes each cue and the Foley artist is satisfied with the performance, the mixer makes a checkmark by the cue, thereby confirming that the cue was actually done.

As the Foley artist and recording mixer work their way through the reel, they may wish to make changes in your layout, usually to accommodate an item the Foley artist wishes to add; perhaps they feel the need to separate cues you had assumed would be done simultaneously. For instance, you may have made notes in a prop channel, such as Foley-7, that you need Jesse James to draw his pistol, snap open the cylinder, and reload six fresh cartridges. Because of intricate maneuvers with entirely different props to simulate the weapon, your Foley artist might tell the mixer that the holster draw and bullet inserts will be done in channel 7 (Foley tracks are referred to as channels) but that he or she wants to redo the gun movement (the subtle metallic rattle) and the cylinder snap open movement in channel 8 to separate the two bits of action.

Figure 17.15 Typical Foley cue sheet log; we start with 8 channel sheets.

Plotting out Foley is extremely important. Cues of different characters cannot be jumbled one after another without realistic separation. Be very predictable and consistent; think ahead to the eventual predubbing process on the rerecording stage and put yourself in the chair of the sound effects mixer. The standard rule is as follows: hero footsteps in the first channel; second hero (or first villain, depending) in the second channel; secondary individual performances in the next channels; then background extras using one or more channels; next, several channels of props—and remember to keep each performance isolated for the sound effects mixer.

Most of your work, unless the budgets are large enough and the Foley schedule long enough, fits most effectively in the 8-channel format. This format fit all analog and most digital tape formats perfectly—8 channels fit into two rolls of 4-channel 35 mm fullcoats perfectly or one 8-channel DA-88. Thinking in groups of 4 and 8 channels was the most logical.

Today, it does not really matter. Recording in Pro Tools we record in a selected Record channel and then drag the renamed cue down into an appropriate channel for playback and get it out of the way. Later, when the Foley editor cuts it up and splits it off for perspective, no matter how many channels you end up with, the session is going to expand de facto because of perspective split editing later. You just want to use the Foley cue sheet as a road map, a blueprint of what you need the Foley crew to perform and supply to sound editorial.

Techniques to Consider

Most Foley expertise you acquire is simply a matter of hands-on experience, getting in and doing it, trying different things, listening to how they sound in playback.

Self-Awareness Tips

You must learn from the start, when around these highly sensitive microphones, to breathe very lightly—not an easy task if you have just completed a rather strenuous cue. I often hold my breath or take very shallow breaths, holding my mouth open so as not to cause any wheezing sounds, for fear the microphone will pick it up.

After a recording mixer reports that a cue was ruined by some extraneous noise (which you probably caused) and it must be done over, you learn to cross the room noiselessly, pretending to be a feather, or you breathe with such a shallow intake as to redefine stealth.

I spent most of the time with my pants off while I was on the Foley stage. (Remember Foley is performed on a dark stage.) I wore black close-fitting cotton bikini shorts or a competition swimsuit. The reason was really quite simple—I could not risk unwanted cloth movement. As your ears become more discerning, you discover how intrusive various cloth materials are. If you wish to perform various props and/or noncloth movement cues as cleanly as possible, you will do anything to achieve the desired level of sonic isolation necessary. Many female Foley artists wear leotards or aerobic exercise garments with little if any excess material.

Grassy Surrogate

One of the best ways to simulate grass is to unwind 100’ or so of old 1/4” recording tape. Place the small pile in the dirt pit. When bunched together or pulled apart for thinner textures, walking through grass, or leaf movement on bushes, is simulated amazingly well.

Snow

Probably the substance that most closely matches the sound of snow is cornstarch. Lay an old bedsheet down over the dirt pit or on a section of the concrete floor, and pour several boxes of cornstarch into the center of the sheet, making a bed approximately 1” thick. With the microphone stand positioned close in and the microphone itself lowered fairly near to the floor, the result is an amazing snow compaction crunch. Most Foley stages are equipped with two stands with identical microphones. As you experiment with placement and balance, you will find that having the second microphone placed back and a little higher affords the recording mixer an excellent opportunity either to audition and choose the better sounding angle or to mix the two microphone sources together for a unique blend.

The only drawback to tromping footsteps through the cornstarch, as you will experience when you spend a good part of the day performing in the dirt pit, is that you kick up a lot of dust and powder particles. It is unavoidable. Hopefully, the Foley stage is equipped with powerful exhaust fans that can be turned on during breaks to filter the air, or it keeps surgical filter masks available. Check the sensitivity of the smoke sensors on the stage, as they often get clogged and silently alert the local fire department to come unnecessarily.

Safety with Glass

You may need to wear a surgical mask if the film you are walking has a great deal of either snow or dirt effects to perform. A smart Foley artist keeps a pair of safety goggles in the box, especially for performing potentially hazardous cues such as broken glass or fire. For The Philadelphia Experiment, we purchased 100 6’-long, 25-watt lightbulbs and mounted them in 100 closely drilled holes on a 2’ × 12’ board. When we performed the sequence in the picture where the actor smashes vacuum-tube arrays with a fire axe, we had our biggest and strongest assistant kneel down to support the board in a vertical position. He wore heavy leather construction gloves and safety goggles. For added protection, we draped a section of carpet over him to shield him from the shower of glass shards. I also wore safety goggles, but I wore black dress gloves so as not to make undue noise.

Because we could not accurately estimate the dynamic strength of the recording, we brought in a backup 1/4” Nagra recorder. This gave us not only a direct recording to 35 mm stripe but also a protection 1/4” recorder in the machine room recording at a tape speed of 7.5 ips and a second 1/4” recorder on the stage itself recording at 15 ips! The 1/4” Nagra recording at 15 ips captured the most desirable effect as I swung a steel bar down through the 100 lightbulbs, resulting in an incredible explosion of delicate glass and vacuum ruptures. I have been ribbed for years by Foley artists who claim that, every so often, they still find shards of those light-bulbs.

Fire

Fire is another tricky and potentially dangerous medium to work with on a Foley stage. While performing some of his own Foley cues for Raiders of the Lost Ark, Richard Anderson used a can of benzene to record the little fire raceways in the Nepal barroom sequence when Harrison Ford (Indiana Jones) is confronted by Ronald Lacey and his henchmen. After a few moments, the fire suddenly got out of control, and, as Richard quietly tried to suppress it, the flame nonetheless spread out quickly, engulfing his shoe as it raced up his leg.

In typical Richard Anderson fashion, he did not utter one word or exclamation but pointed for his partner to grab the fire extinguisher. It had been moved before lunch, however, and was no longer in its place. Steve Flick dashed through the soundproof door to find one as Richard breathlessly jumped around trying to put out the growing threat. He saw the 3’-deep water pit and jumped in—only it was not full of water, and in a seemingly magical single motion jumped instantly out again. He grabbed the drapes under the ledge of the screen and used them to smother the flames just as Steve Flick appeared through the doorway, fire extinguisher at the ready.

Figure 17.16 For years the author taught students some of the most aggressive hands-on Foley. Here a student is performing torch whooshes with an open flame using rubber cement on the end of a wooden paint stir stick. It is vital to learn the correct safety techniques to avoid accidents and disasters. Photo by David Yewdall.

Because of the increased hazard and potential injuries posed by performing various types of fire on a Foley stage, most sound facilities either discourage or forbid anything more than matches and a lighter. The days of burning flares and destroying blood bags with fire on stage (as I did for John Carpenter's The Thing) are few and far between. This is why I teach careful and exceptional planning with the sound facility and with the studio fire department in attendance.

The supervising sound editor should plan for these sound cues to be performed and recorded in any venue other than the Foley stage, whenever possible. Naturally, the sync-to-picture advantage of being able to perform cues such as the actor carrying and waving a torch around is vital to do in the controlled environment of a Foley stage. Even with the studio fire department supervising during custom recording of a blowtorch in Jingle All the Way, the glowing metal of a 55-gallon drum reached a certain dangerous hue, and the fire captain stepped in to say enough.

The Most Terrifying Sound Effects in the World Come from Your Refrigerator!

When it comes to slimy entrails and unspeakable dripping remnants, few have done it longer or better than John Post. Considered the inspirational sponsor and teacher of virtually half the Foley artist cadre of Hollywood. As stated earlier, John has trained more than his share of aspiring sound effects creators. As of the writing of this book, John is in his fifth decade of working the pits and creating the audio illusions that make his work legendary.

I always liked working with John. He brought a whole different performance to even the simple act of walking. Many Foley artists made footfalls on the right surface and in sync with the action onscreen, but Johnny took the creation to a whole new level. It was not just a footfall on the correct surface: the footstep had character, texture, and often gave an entire spin on the story. I remember being on the rerecording stage when the director stood up and paused the mixing process. He asked the mixers to back up and replay the footsteps of the actress crossing a room. After we played the cue again, the director turned to us with an amazed expression. He was fascinated about how John Post had completely changed the performance of the scene. Before Johnny performed the footsteps, the actress simply crossed the room. During the Foley session, however, Johnny built in a hesitation by the actress on the offscreen angle and then continued her footsteps with a light delicacy that bespoke insecurity. This not only completely changed the onscreen perception of the actress's thoughts and feelings, but also greatly improved the tension of the moment. Johnny's very act of craftsmanship separates the mechanical process from art. He always approaches his Foley responsibilities as part of the storytelling process. Many agree that John Post knew how to walk women's footsteps better than women. John Post preformed the original autopsy sound effect cue for The Thing. This recording has been used in perhaps 100 or more motion pictures and/or television shows since.

As a general rule, I do not reveal how an artist makes magic. Since this book is about sharing and inspiration, however, I will divulge to you how John Post made this famous sound. Johnny set up a large heavy bowl on the Foley stage. He then broke half a dozen eggs and mixed them thoroughly, just as if he were preparing a scrambled-egg breakfast. After the Foley mixer received a volume level test and readjusted the microphone positioning, Johnny dipped several sheets of paper towels into the eggs until they were completely saturated. He then lifted the paper towels out of the brew and voice slated what he was doing. Johnny proceed to play with the paper towels, squeezing them, pulling them through his tightened fingers, and manipulating the egg goo to replicate that to which our ears and imagination responded.

Figure 17.17 Foley artist John Post squishes paper towels dipped in a bowl of raw eggs to make autopsy guts for John Carpenter's The Thing. Photo by David Yewdall.

Hush Up!

You learn very early as you work on a Foley stage or out in the field recording sound effects to keep your mouth shut—even when the unexpected happens. If that crystal bowl slips out of your hands and smashes to the floor, you want a clean and pristine recording of a crystal-bowl smash, untouched by a vocal outburst of surprise or anger. After all, it may end up in the library as one of the proudest accidental sound effects. Every sound editor has a private collection of special sounds attributable to this useful advice.

Zip Drips

Another classic sound is the zip-drip effect. This tasty little sweetener effect is often performed to add spice, such as the sizzling power line that extended over the downtown square in Back to the Future after Christopher Lloyd (Dr. Emmett Brown) made the fateful connection allowing lightning to energize the car that sent Michael J. Fox forward into the future. The Foley artist, John Roesch, burned a piece of plastic wrap from a clothing bag, causing the melted globule to fall past the microphone, making a zip-drip flight.

The same technique was used when I supervised The Thing 4 years earlier, only I burned the plastic fin of a throwing dart. As I studied the frame-by-frame action of Kurt Russell lighting a flare before descending into the ice cavern of the camp, I saw a small spark fly off the striker. I wanted to sweeten this little anomaly with something tasty, as there was a moment before the three men turned to go below. We recorded several zip drips for this, but as I played them against the action, I noticed that, because of the Doppler effect caused by the globule approaching and passing the microphone so quickly, it made the zip-by sound ascending, instead of descending as you might expect. (If you listen closely to the above mentioned sequence in Back to the Future, you will notice that the globules falling from the power line sound ascending, instead of descending.) Wanting the spark from the flare to have a descending feel, I simply took the recording of the zip drip and made a new transfer, playing the original recording backward. It may seem like a small, insignificant bother, but this kind of attention to detail adds to a more pleasing overall performance, regardless of whether the audience is aware of the detail.

For years we have been brainwashed about how dumb the population out there is. What a bunch of hooey! The audience is not dumb. They are very intelligent and sophisticated, and they notice absolutely everything.

EDITING FOLEY

In the days of magnetic film, we had transportation runners wheeling hand dollies into the editorial rooms stacked high with hundreds of pounds of 35 mm stripe, hundreds of 1000’ rolls. Each roll represented a single Foley channel of a single reel of a movie. These were called string-offs because they were transferred one channel at a time to one roll of film at a time. We threaded up each roll on the Moviola and interlocked the start mark with the Academy start frame of the Foley string-off.

For hours we rolled back and forth, checking and correcting sync, cutting out frames to condense, adding frames of blank film to expand. Our Rivas splicers clacked and whacked every few seconds with another cut decision. It was not unusual to use up an entire roll of splicing tape on one channel roll of Foley. Back then, one roll of 35 mm white perforated splicing tape cost over $15. Each foot of 35 mm magnetic stripe film cost 2.5¢ (from the manufacturer) and as much as 7b a foot for the labor to transfer it. That means that every foot of stripe was costing approximately a dime. If we held the show to 8 Foley tracks per reel, we burned off at least 80,000 feet of Foley stripe transfer. Some sound facilities were using an average of 22 to 44 channels of Foley for action features.

The Foley cutter is just as much an artist as the person performing Foley on stage. An interesting axiom is that precisely cut Foley sometimes does not play as well as creatively cut Foley. While cutting Foley on Predator 2, during the sequence where Glover and Paxton chase the alien up to the rooftop, I cut each and every step in precise sync. The men burst out of the room, into the hallway, slamming up against the wall, turning and running down the hall, turning and vaulting up steel stairs, steeplechase-style running and maneuvering. I cut it all in exact sync, using three rolls of splicing tape per Foley roll. Then I played it at real time. It felt funny. I knew it was cut in exact sync, but exact sync wasn't evoking the passion and rhythm of the sequence.

I pulled it apart and spent another day just cutting movements and turns to accent the sweep and moment of the action. I discovered that, by changing the footsteps that had been performed, by moving the order around so that a more forceful footfall was replaced by a lighter one, and the heavier one placed in a more strategic spot to emphasize a particular change of body direction, the performance took on a whole different spin. Suddenly, power and energy backed up the visuals on the screen.

One of the harder techniques to master is cutting footsteps in precise sync when you cannot see the feet. Most beginners think this is easy stuff. After all, you cannot see the feet, so just let the footsteps roll. It doesn't play quite right, however. To cut footsteps when all you see are talking heads and torsos, watch the shoulders of the actors. Flip frame slowly. Each frame of walking has a natural blur to it, except when the foot has just impacted the ground. That one frame has a perfect focus. To that frame you sync the footstep sound. If the footsteps still feel odd, try changing feet. Sometimes sliding down the left foot impact sound and syncing it to the right footstep make all the difference.

Some editors like to cut sync on footsteps one frame prior to focus frame for visual impact. Because light travels faster than sound, some think it gives a better appearance of sync when playing at normal speed as heard in the theatre.

Before I start cutting, I magnify the waveforms of the tracks so high that they become blocks of color. This way, I can see all of the most sensitive and subtle recordings without having to take the time to play it all. I will highlight and cut out all of the strips of silence in between the individual cues and then highlight and rename the regions.