Chapter 14

Sound Editorial

Ultra Low-Budget Strategies

“I know what I said—but now we're dealing with reality!”

You just finished reading about the structured, more traditional techniques and disciplines for recording, editorial preparation, and delivery of the myriad sound cues necessary to create the theatrical film experience known as the soundtrack—and you think all this book talks about is big-budget features with big teams of craftspeople to get the job done. Well, before we discuss the dialog editing, ADR and looping techniques, the world of Foley, music, and the rerecording process, I think we should pause and discuss the fact that a great deal of the work you will do will not and cannot afford the budget requirements to mount the kind of sound job that you will find yourself faced with.

I assumed that as you have been reading this book you understood one extremely important axiom, and that is that the art form of sound does not change, no matter what budget and schedule is on the table. All of the audio recording techniques, the science, and the pure physics of the soundtrack of a film do not change— only the strategies of how you are going to get your arms around the project and solve it.

The upcoming chapters regarding the dialog, ADR, Foley, music collaboration, and edit preparation in concert with the strategies of the rerecording mix process apply to the development of the final soundtrack the same way, whether you are working on a gigantic $180 million space opera or if you are working on an extrafeatures behind-the-scenes documentary for a DVD release or a student film. The only differences are the dollars allocated in the budget and the schedule demands that will, if you have been paying attention to what you have read thus far (and will continue to read about in the following chapters), dictate to you exactly how you are going to develop and deliver a final soundtrack that will render the fullness of the sound design texture and clarity of a sound budget with 10 times the dollars to spend, to as much as 100 times the budget that the blockbuster films command.

I could not have supervised the sound for 11 Roger Corman films if I did not understand how to shift gears and restructure the strategies of ultra low-budget projects. That does not mean that all sound craftspeople know how to shift back and forth between big-budget to ultra low-budget projects and maintain the perception of quality standard that we have come to expect from the work we do.

There are many who can only practice their art form (whatever specific part of the soundtrack that he or she is responsible for) in the arena of mega-budget films, where they can get approval to do custom recording halfway around the world, have unlimited ADR stage access, and be able to spend two or more days to perform the desired Foley cues per reel.

Conversely, there are craftspeople who can tackle, successfully develop, and deliver a final soundtrack for ultra low-budget projects but who cannot structure, strategize, and oversee the sound supervisorial responsibilities of mega-budget pictures.

Then there are those of us who move back and forth between huge-budget jobs and tiny-budget jobs at will. Over the years I have observed that those sound craftspeople who started their careers in a sound facility that was known for, and specialized in, big-budget pictures usually had an extremely difficult time handling the “I ain't got no money, but we need a great soundtrack regardless” projects.

This is the realm of disciplined preplanning—knowing that it is vital to bring on a supervising sound editor before you even commence principal photography. This is where the triangle law we discussed in Chapter 4 regarding the rule of “you can either have it cheap, you can have it good or you can have it fast” really rises up and demands which two choices that all can live with.

Even if the producer is empowered by how important the soundtrack is to his or her project, the majority of first-time producers almost never understand how to achieve a powerful soundtrack for the audience, but they especially do not know or understand how to structure the postproduction budget and realistically schedule the post schedule.

This has given rise to the position commonly known as the postproduction supervisor, who, if you think about it, is really just an adjunct producer. The many postproduction supervisors whom I have had the misfortune to work with do not know their gluteus maximus from a depression in the turf. With only a couple of exceptions, postproduction supervisors almost always just copied and pasted postproduction budgets and schedules from other projects that they think is about the same kind of film that they are presently working on. Virtually, without fail, these projects always have budget/schedule issues because every film project is different and every project needs to have its own needs customized accordingly. I have been called into more meetings where the completion bond company was about to decide whether or not to either shut the project down or take it over, and on more than one occasion their decision pivoted on what I warranted that I could or could not do in the postproduction process. By the way, this is an excellent example of why it is vital to always keep your “word” clean—do what you say you will do, and if you have trouble or extenuating circumstances to deal with, do not try to hide it or evade it. Professionals can always handle the truth. I tell my people, “Never lie to me, tell me good news, tell me bad news—just tell me the truth. Professionals can problem-solve how to deal with the issues at hand.”

YOU SUFFER FROM “YOU DON'T KNOW WHAT YOU DON'T KNOW!”

Every film project will tell you what it needs—if you know how to listen and do some simple research. You can really suffer from what I call, “You don't know what you don't know.” It can either make you or break you. Think about the following items to consider before you dare bid and/or structure a soundtrack on an ultra low-budget project.

What genre is the film? It is obvious that a concept-heavy, science-fiction sound project is going to be more expensive to develop a soundtrack for than if the film is an intimate comedy-romance.

Read the script and highlight all pieces of action, location, and other red flags that an experienced supervising sound editor has learned to identify, that will surely cost hard dollars.

Look up other projects that the producer has produced, noting the budget size that he or she seems to work in.

Look up other projects that the director has directed, and talk with the head rerecording mixer who ultimately mixed the sound and knows (better than any other person on that project) the quality and expertise of preparation of the prior project.

Look up other projects for which the picture editor has handled the picture editing process. Look him or her up on IMDb (Internet Movie Database) and pick several pictures that are credited to him or her. Scroll down to the “Sound Department” heading. Jot down the names of the supervising sound editor(s) and especially the dialog editor. Without talking about the current project you are considering, ask these individuals about the picture editor; you will learn a wealth of knowledge, both pro and con, that will impact the tactics and political ground that you will be working with.

Case in point: When Wolfgang Petersen expanded his 1981 version of Das Boot into his “director's cut,” why did he not have Mike Le Mare (who was nominated for two Academy Awards on the original 1981 version) and his team handle the sound-editorial process? For those who understand the politics of the bloody battlefield of picture editorial, understand the potential of being undermined by the picture editor. You need to find out as much as you can about him or her, so you can navigate the land mines that you might inadvertently step on.

SOUND ADVICE

A producer really needs to engage the supervising sound editor, and have him or her involved from the beginning when working to a fixed budget. A supervising sound editor will always have a list of production sound mixers that come recommended—not just name production sound mixers, but mixers who have a dependable track record of delivering good production sound on tough ultra low-budget projects.

If you think about it, it makes perfect sense. The supervising sound editor is going to inherit sound files from the very person he or she has recommended to the producer. When it comes to protecting your own reputation and an industry buzz that your word is your bond, then friendship or no friendship, the supervising sound editor is going to want the best talent who understands what to get and what not to bother with under such budgetary challenges.

I will not rehash what we have already discussed in Chapter 5, because the art form of what the production mixer will do does not change. But the choice of tools and knowing how to slim down the equipment costs and set protocols in order to save money are important.

When the supervising sound editor advises the producer on specific production sound mixers to consider, he or she will also go over the precise strategies of the production sound path—everything from the production sound recording on the set, through picture editorial, from locking the picture and the proper output of the EDL and OMF files, and, of course, how to structure the postsound-editorial procedure. On ultra low-budget projects, it is vital that the producer understand the caveats of a fixed budget, so that the supervising sound editor can guarantee staying on budget and on schedule, so long as the “If. . . ” clauses do not rise up to change the deal.

The “If” disclaimers can, and should, include everything from recording production sound a particular way, that proper backups are made of each day's shoot prior to leaving the hands of the production sound mixer. All format issues must be thoroughly discussed and agreed on, through the usage of sound (including temp FX or temp music) during the picture editorial process to locking the picture and handing it over to the supervising sound editor. The producer must be aware of what can and what cannot be done within the confines of the budget available.

With very few exceptions, projects that run into postproduction issues can be traced back to the fact that they did not have the expert advice of a veteran supervising sound editor from the beginning.

PRODUCTION SOUND

It is very rare to come across an ultra low-budget project that has the luxury of recording to a 4-track (or higher) recorder. You usually handle these types of production recordings in one of two ways.

1. |

You record to a sound recorder. Whether the project is shot on film or shot on video, the production track is recorded on a 2-track recorder, such as a DAT recorder or a 2-track direct-to-disk. |

2. |

If the project is being shot on video, especially if in high-def, the production sound mixer may opt to use only an audio mixer, such as the Shure mixer shown in Figure 14.1. The output from the audio mixer is then recorded onto the videotape, using the camera as the sound recorder, which also streamlines the log-and-capture process at picture editorial. |

Figure 14.1 The Shure FP33 3-Channel Stereo Mixer. This particular model shown is powered by two 9-volt batteries.

One decision you will have to think about, if you are shooting video and you wish to opt for the production sound being recorded to the videotape, is whether the project setups are simple or highly complex. If the camera needs to move, enjoying more freedom will mean that you do not want a couple of 25’ axle audio cables going from the sound mixer outputs into the back of the video camera's axle inputs. At the very least, this will distract the camera operator any time the camera needs to be as free as possible.

The best way to solve the cable issue is to connect the sound mixer outputs to a wireless transmitter. A wireless receiver is strapped to the camera rig with short pigtail axle connectors going into the rear of the camera.

Double Phantoming—The Audio Nightmare

Whether you opt for a cable connection from the sound mixer to the camera or if you opt to have a wireless system to the camera, the first most important thing to look out for is the nightmare of “double phantoming” the production recording.

Video cameras have built-in microphones. Any professional or semiprofessional video camera has XLR audio imports so that a higher degree of quality can be achieved. Because a lot of this work is done without the benefit of a separate audio mixer, these cameras can supply phantom power to the microphones.

When the crew does have a dedicated production sound mixer, using an audio mixer, you must turn the phantom power option off in the video camera. The audio mixer has a LINE/MIC select switch under each XLR input. The audio mixer needs to send the phantom power to microphones, not the video camera, as the output becomes a LINE (not a microphone) issue.

If the video phantom power select is turned on, then the camera will be sending phantom power in addition to the audio mixer, automatically causing a “double phantom” recording, which will yield a distorted track. No matter how much you turn the volume down, the track will always sound distorted. The next law of audio physics is that sound, once recorded “double phantomed,” cannot be corrected, is useless, and can only serve as a guide track for massive amounts of ADR.

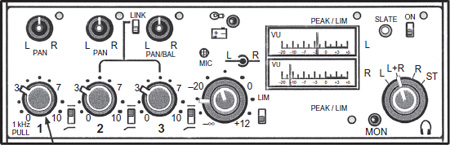

Using the Tone Generator

Different manufacturers have different means of generating a known line-up tone for the user. In the case of the Shure mixer (Figure 14.1), the first microphone input volume fader (on the far left) controls the tone generator. You simply pull the knob toward you, turning on the generator and creating a 1 kHz tone. Leaving the PAN setting straight up (in the 12 o'clock position) will send the 1 kHz signal equally to both channel 1 (left) and channel 2 (right). The center master fader can then be used to calibrate the outputs accordingly. Notice the icon just above the master fader which indicates that the inside volume control knob is used for channel 1 (left) and the outside volume control ring is used for channel 2 (right).

If you line up both channels together you will send the line-up tone out to the external recording device, whether it be the video camera or a 2-channel recorder such as a DAT.

The production sound mixer coordinates with the camera operator to make sure that the signal is reaching the camera properly, that both channels read whatever –dB peak meter level equals 0 VU—such as –18 dB to as much as –24 dB—and that the recording device (whether it be an audio recorder or the video camera) has its “phantom power” option turned OFF. Once the recording device (audio recorder or video camera) has been set, only the production sound mixer will make volume changes.

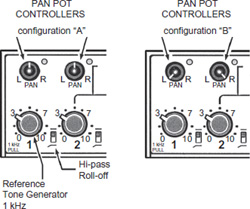

The Pan Pot Controllers

If you are using a single microphone and wish to have both channels receiving the signal, then you should leave the Pan Pot Controller (above the microphone input volume fader being used) in the straight-up (12 o'clock position), as shown above in Figure 14.2.

If you are using two microphones, and you wish to have each channel kept in its own dedicated channel, then you push in on the Pan Pot Controller knob. It will then spring out so you can turn it to either hard left or hard right. This will send microphone input 1 to channel 1 (left) only and microphone input 2 to channel 2 (right) only, as shown in Figure 14.3. This does not necessarily make a stereophonic recording. Unless you set the microphones up properly in an X-Y pattern, or use a stereo dual-capsule microphone, you will face potential phasing issues and no real disciplined stereophonic image. This configuration is best if your boom operator is using a boom mic and a wireless mic is attached to an actor—or two wireless mics, one on each actor—or two boomed mics that by necessity need to have the mics placed far enough apart that one microphone could not properly capture the scene.

Also note in Figure 14.2 that there is a Flat/Hi-Pass setting option just to the right of each microphone input volume fader. Standard procedure is to record Flat, which means the selector would be pushed up to the flat line position.

If you really feel like you need to roll off some low end during the original recording, then you would push the selector down to the hi-pass icon position. Just remember, if you decide to make this equalization decision at this time, you will not have it later in postproduction. You may be denying some wonderful low-end whomps, thuds, or fullness of production sound effects. You must always record with the idea that we can always roll off any unwanted low-end rumbles later during the rerecording process, but you cannot restore it once you have chosen to roll it off.

Figure 14.2 Two recording strategy setups.

Figure 14.3 Two recording strategy setups.

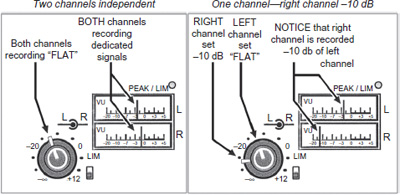

Two Recording Strategies

In Figure 14.3, “two channels independent” requires that the Pan Pot Controller above each microphone input volume fader be set to either hard left or hard right, depending on which channel the production sound mixer wants the signal to be sent. This is also the setup setting you want if you are recording stereophonically.

In Figure 14.3, “one channel—right channel –10 dB” requires that the Pan Pot Controller above each microphone input volume fader be set to the straight-up (12 o'clock) position. This will send a single microphone input equally to the master fader, only you will note that after you have used the 1 kHz tone generator to calibrate the desired recording level coming out of the audio mixer to either the camera or to a recording device, you will then hold the inside volume control knob in place (so that the left channel will not change) while you turn the outside volume control ring counterclockwise, watching the VU meter closely until you have diminished the signal 10 dB less than channel 1. In the case of Figure 14.3, the left channel is reading –3 dB (VU) so you would set the left channel to –13 dB (VU). This is known as “right channel –10 dB”—which is used as a volume insurance policy, so to speak.

During the recording of a scene there may be some unexpected outburst, slam of a door, a scream following normal recording of dialog—anything that could over-modulate your primary channel (left). This becomes a priceless insurance policy during the postproduction editing process, where the dialog editor will only be using channel 1 (left), except when he or she comes upon such a dynamic moment that overloaded channel one. The editor will then access that moment out of channel 2 (right), which should be all right, due to being recorded –10 dB lower than the primary channel. Believe me, there have been countless examples where this technique has saved whole passages of a film from having to be stripped out and replaced with ADR. As you can see, this is a valuable technique on ultra low-budget projects.

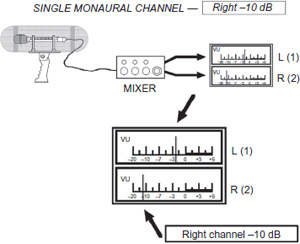

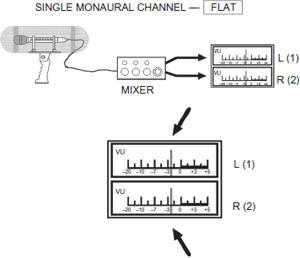

Single Monaural Channel—Flat

Figure 14.4 shows a single microphone with both channels recording the same signal at the same volume. The Pan Pot Controller above the microphone input volume fader is set straight up to send the audio signal evenly to both left and right channels.

Figure 14.4 One microphone for both channels—FLAT.

Figure 14.5 One microphone for both channels—channel 2 (right) set –10 dB from channel 1 (left).

Single Monaural Channel—Right –10 dB

Figure 14.5 shows a single microphone. The Pan Pot Controller above the microphone input volume fader is set straight up to send the audio signal evenly to both left and right channels; however, the master audio fader is set right channel –10 dB less than left channel.

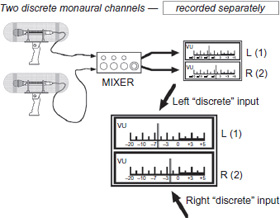

Two Discrete Monaural Channels—Recorded Separately

Figure 14.6 shows two microphones with the Pan Pot configurations set to hard left and hard right, thus being able to use two different kinds of mics. The production sound mixer must make precise notes on the sound report what each channel is capturing—for example, channel 1: boom mic, channel 2: wireless. The microphones do not have to be the same make and model, as this configuration is not for stereo use but is simply isolating two audio signals. It could be you have a boom operator favoring one side of the set where actor A is and you have your cable man, now acting as a boom operator, using a pistol-grip-mounted shotgun mic, hidden behind a couch deep in the set where he or she can better mic actor B, and so forth.

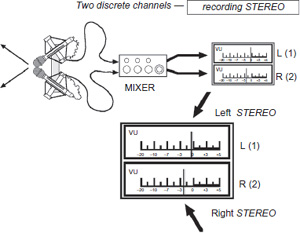

Two Discrete Channels—Recording Stereo

Figure 14.7 shows two microphones in an X-Y configuration to greatly reduce phasing issues. The pan pot configurations are set to hard left and hard right. To record a correct stereophonic image both microphones must be identical.

The most dramatic phasing problems take place when the audio event, such as a car-by (as discussed in Chapter 10), causes a cancellation wink-out as the car (or performing item) crosses the center point, whereby the audio signal, which was reaching the closer microphone diaphragm a slight millisecond more quickly than the far microphone, is now going to reach the second microphone diaphragm before it reaches the first one. This center point area of crossing over is where the phasing cancellation wink-out area comes into play. If the two channels are folded together, which often happens somewhere in the postproduction process—and certainly will be noticed if it is televised and the stereo channels are combined in a mono playback option—there will be a drop-out at the center point. This is why you want the two diaphragms as close together as possible.

Figure 14.6 Two discrete monaural channels.

Figure 14.7 Stereophonic recording using X-Y microphone configuration. Photo courtesy of Schoeps.

Notice that in the Schoeps X-Y configuration, the microphone capsules are actually over/under, getting the two diaphragms as close as possible to zero point.

SOUND EDITING STRATEGIES

Budget restrictions should only compel you to rethink how you will get your arms around the soundtrack. I have heard too many editors slough it off as, “I'm not going to give them what they're not paying for.” I suppose that kind of attitude makes one feel better about not having a budget to work with, but it backfires on you, because when all is said and done nobody will (A) remember, (B) have knowledge of, or (C) give a damn what the budget and/or schedule restrictions were. Your work is up there on the screen, and that is all that matters. You must know how to cut corners without compromising the ultimate quality of the final soundtrack.

This is where veteran experience pays off. Some of the best supervising sound editors in features today learned their craft by working in television, a medium that always was tight and fast. It is far more difficult for an editor who only knows how to edit big-feature style to shift gears into a tight and lean working style.

You have to learn how to work within the confines of the budget and redesign your strategies accordingly. The first thing that you will have to decide is how to do the work with a very tight crew. Personally, I really learned how to cut dialog by working on the last season of Hawaii Five-0, where they would not allow us to ADR anything. We had to make the production track work—and we did a show every week!

I have developed a personal relationship with several colleagues, each with his or her own specialty. When we contract for a low-budget project, we automatically know that it is a three-person key crew. I handle the sound effects design/editing as well as stereo backgrounds for the entire project; Dwayne Avery handles all of the dialog editing, including ADR and Group Walla editing; and our third crewmember is the rerecording mixer Zach Seivers. The only additional talent will be the Foley artist(s), and the extent of the Foley work will be directly index-linked to how low an ultra low-budget project can afford. Vanessa Ament, a lead Foley artist/supervisor, describes her part of the collaboration:

Sometimes I think Foley artists and Foley editors lose sight of what Foley is best used for. There is a tendency to “fall in love” with all the fun and challenge of doing the work, and forgetting that edited sound effects are going to be in the track also. Thus, artists and editors put in sounds already covered by effects. The problem with this is threefold. First, the sound effects editor can pull certain effects faster out of the library or cut in recorded field effects that are more appropriate without the limitations of the stage. Second, the Foley stage is a more expensive place to create effects than the editing room, and third, the final dubbing mixer is stuck with too many sounds to sort through. I remember a story about a very well-respected dubbing mixer who was confronted with 48 tracks of Foley for a film and, in front of the editor, tore the pages with tracks 25 through 48 up, tossed them behind him and requested that tracks 1 through 24 of Foley be put up for predubbing. The lesson here is: think of the people who come after you in the chain of filmmaking after you have finished your part.

Figure 14.8 Vanessa Ament, lead Foley artist performing props for Chain Reaction. The other Foley artist assisting her is Rick Partlow. Photo by David Yewdall.

On Carl Franklin's One False Move, Vanessa Ament only had two days to perform the Foley, because that was all the budget could afford. It was absolutely vital that Vanessa and I discuss what she absolutely had to get for us, and what cues she should not even worry about, because I knew that I could make them myself in wild recordings or I had something I could pull from the sound effect library. And that is really the key issue: Foley what you absolutely have to have done. If your Foley artist has covered the project of all the have-to-get cues and there is any time left over, then go back and start to do the B-list cues until your available time is up. You have to look at it as how full the glass is, not how empty it is.

For the dialog editor, it becomes a must to work with OMF, which means that the assistant picture editor(s) had to do their work correctly and cleanly—as I have said before, “junk-in, junk-out.” If the dialog editor finds that a reprint does not A-B compare with the OMF output audio file identically, then you are in deep trouble. If you cannot rely on the quality of the picture editorial digitizing process, then you are going to have to confront the producer with one of the “If” disclaimers that has to affect your editorial costs. “If” you cannot use the OMF, and the dialog editor has to reprint and phase match, there is no way you can do the editing job on the same low-cost budget track that you are being asked to work with.

I have seen this “If” rise up so many times that I really wish that producers have to be required to hire professional experts who really know the pitfalls and disciplines of digitizing the log-and-capture phase of picture editorial. So many times, producers hire cheap learn-on-the-job interns to do this work because they save a lot of money, only to be confronted in postproduction with the fact that they will be spending many times as much money to fix it as it would have cost to do it right the first time.

It is also at this stage of the project that you really understand how valuable a good production sound mixer who understands the needs and requirements of postproduction is to an ultra low-budget project. He or she will understand to grab an actor who has just a few lines as bit parts, and on the side, record wild tracks of them saying the same lines with different inflections, making sure that their performance is free and clear of the noise that constantly plagues a location shoot.

I cannot tell you how much the production sound mixer Lee Howell has saved his producer clients by understanding this seemingly simple concept of wild tracks of location ambiences and sound reports with lots of notations about content. Precise notes showing the wild tracks of bit players will save a producer from flying actors in for ADR sessions to redo just a handful of lines. It becomes the fast track road map to where the good stuff is.

A good production track is pure gold. It is literally worth gold when you do not have a budget to do a lot of ADR or weeks and weeks of dialog editors to fix tracks.

I can always tell the amateur dialog editor. His or her tracks are all over the place, with umpteen tracks. You must prepare your dialog with ambience fills that make smooth transitions across three or four primary tracks, not including P-FX and X-tracks (you will read about dialog strategy in Chapter 15).

Have your director review a ready-to-mix dialog session, not during the mix but with the dialog editor, making his or her choices of alternate performances then and there, rather than wasting valuable mixing time deciding which alternate readings he or she would prefer.

Not all supervising sound editors, or for that matter, sound editors who support the supervisor's strategies, can shift from mega-budget projects to ultra low-budget projects with a clear understanding of the art form and the necessary strategies to tackle either extreme without waste or confusion. Clancy Troutman, the chief sound supervisor for Digital Dreams Sound Studios located in Burbank, California, has worked on projects that challenge such an understanding. Clancy is a second-generation sound supervisor, having learned his craft and the disciplines of the art form, first as an apprentice to and then as a collaborator with his father, Jim Troutman, veteran of several hundred feature films. Jim's vast experience, knowledge of sound, creativity, and expertise have teamed him over the years with some of Hollywood's legendary directors such as Steven Spielberg, Mel Brooks, Peter Bogdanovich, and Sam Peckinpah. Clancy worked under his father on sound designing and sound editing for Osterman Weekend, Life Stinks, The Bad Lieutenant, Fast Times at Ridgemont High, and Urban Cowboy. Clancy came into his own, stepping into the supervising sound editor position with such projects as Beastmaster, Cop with James Woods, and Cohen & Tate with Roy Scheider. Other challenging projects include supervising the sound for Police Academy: Mission to Moscow, Hatchet, The Pentagon Papers, and Toolbox Murders, to name just a few. His work on Murder She Wrote; China Beach; and Thirtysomething honed his skills in the world of television demands and challenges, earning him the supervising sound editor chores for the popular cult television series The Adventures of Brisco County Jr. starring Bruce Campbell. This eclectic mix of product has given Clancy the understanding of how to shift back and forth between traditional budgets and schedules to ultra low-budget strategies. Even though Clancy has amassed one of the largest sound effect libraries in the business, he really believes in the magic and value of the production sound recordings captured on location. Collaborating with clients to yield as much bang-for-the-buck as possible has been both Clancy's challenge and ultimate satisfaction with problem solving the project at hand. He loves to design and create a unique sound experience for the film that, for the present, only lives in the client's imagination.

Figure 14.9 Clancy Troutman oversees the progress of his sound designer, Scott Westley, at Digital Dreams in Burbank, California. Photo by John LeBlanc.

THE EVOLUTION OF BLENDING EDITOR AND RERECORDING

MIXER

Those of you who have not been part of the film and television sound industry for at least the past 25 years cannot truly understand why things have worked the way they have and why there is so much resistance to the evolution of the sound editor and the rerecording mixer moving closer together and becoming more one and the same.

The traditional rerecording community struggles to remain a closed “boys club”—this is no secret. Since the days when the head rerecording mixer (usually handling the center chair or dialog chores) literally reigned as king on the rerecording stage, he could throw out anything he wanted to. Many a reel got “bounced” off the stage because the head mixer did not like how it was prepared or did not care for the sound effect choices. Mixers often dictated what sounds to be used, not the sound editor.

Even when I started supervising sound in the late 1970s, we would see, and sometimes be a part of, butting heads with the head mixer who ruled the stage and held court. The major studios were not the battleground where change was going to take place. It took independent talent such as Walter Murch and Ben Burtt, who had the directorial/producerial leadership, to give them their freedom.

I remember how stunned I was when I was supervising the sound for John Carpenter's The Thing. We were making a temp mix for a test audience screening. The Universal sound department was already upset that a Universal picture was not going to be left to Universal sound editors and that ADR and Foley chores would not use Universal sound facilities, and worst of all, the final rerecording mix was not going to be at Universal but across town at Goldwyn.

I could write an entire book on postproduction politics and the invisible mine field of who controls what and when you should check that stinging sensation in your back that might be something more than just a bad itch.

We no sooner got through the first 200’ of reel 1 when I put my hand up to stop. The head rerecording mixer did not stop the film. I stood up, with my hand up—“Hold it!”

The film did not stop. I had to walk around the end of the console, step up on the raised platform, and as I paced toward the head mixer, he hit the Stop button, stood up, and faced me square on. “What seems to be the problem?”

Then I made one of the greatest verbal goofs, the worst thing that I could possibly have said to a studio sound mixer. “You're not mixing the sound the way I designed it.”

Snickers crossed the console, as the head mixer stood face-to-face with me, holding back laughter. “Oh, boys, we are not mixing the film the way Mister Yewdall has designed it.”

He started to tell me that he was the head mixer and by god he would mix the film the way he saw fit, not the way I so-called designed it.

Naturally, I had a problem with that. We stood inches apart, and I knew that this was not just a passing disagreement. This was going to be a defining moment. I knew that the Universal crews were upset that they were not doing the final mix; I knew that the temp mix was a “bone” thrown to them so they would not be completely shut out of the process. John Carpenter had mixed all of his films with Bill Varney, Gregg Landaker, and Steve Maslow over at Goldwyn Studios in Dolby stereo and he certainly intended that The Thing was also going to be mixed by his favorite crew; the political battle was rumbling like a cauldron.

I informed the head mixer that he was going to mix the film exactly as I had conceived it, because I had been hired by John Carpenter a year before principal photography had even started, developing the strategies and tactics of how to successfully achieve the soundtrack that I knew John wanted. John wanted my kind of sound for his picture, and I owed my talent and industry experience to John Carpenter, not to studio political game-playing. To make matters worse, Universal Studios did not want the film to be mixed in Dolby stereo, saying that they did not trust the matrixing. They said it was too undependable—and boy, that resulted in an amazing knockdown, drag-out battle royal late one night in the “black tower” with all sides coming to final blows.

So, now I stood there, eyeball-to-eyeball with the head mixer, knowing I did not dare flinch. He then made a mistake of his own, when he said, “Maybe we should get Verna Fields involved in this decision.” (Verna Fields was, at that time, president of production for Universal Studios.)

I agreed. And before he could speak I told the music mixer her telephone extension. I could tell from the head mixer's eyes that he was caught off guard that I even knew her number. But, we literally stood there like statues, staring at each other with total resolve while Verna Fields left the Producers Building and paced past the commissary and into the sound facility.

I didn't even have to look; I recognized the sound of her dress as she stormed into the room. Those of you who have had the honor of knowing Verna, know exactly what I am talking about; those of you who didn't, missed out on arguably the most powerful woman Hollywood has ever known, certainly one of the most respected.

“What seems to be the problem here?!” she demanded.

The head mixer thought he was going to have a lot of fun watching Verna Fields rip a young off-the-lot whippersnapper to ribbons. With a sly smirk he replied, “I don't have a problem, but it seems Mister Yewdall does.”

Verna was in no mood for games. “And that is?”

I kept my eyes locked onto the head mixer, for to look away now would be a fatal mistake. “I told your head mixer that he is not mixing this film the way I designed the sound.”

The head mixer was doing everything to contain himself. He just knew that the “design” word was going to really end up ripping me to pieces, and with any luck, I would get fired from the picture.

Instead, Verna's stern and commanding voice spoke with absolute authority. “We are paying Mister Yewdall a great deal of money to supervise and design the sound for this motion picture, and you will mix it exactly as he tells you.”

If I had hit the head mixer with a baseball bat, it would not have had as profound an effect. It was as if a needle had popped a balloon or you had just discovered your lover in bed with somebody else! I still did not turn to her. I actually felt sorry for the head mixer for how hard it had hit him.

“Are there any other issues we need to discuss?!” demanded Verna.

The head mixer shook his head weakly and turned back to his chair. I turned to see Verna; her thick Coke-bottle glasses magnified the look in her eyes. I nodded my thanks to her as she turned to leave.

Independent sound mixing had gone on for some time, but not on the major studio lots. By noon it was all around town. The knife had cleanly severed the cord that the head mixer ruled as king. The role of the supervising sound editor suddenly took a huge step forward. The unions tried to fight this evolution, and as long as we were working on 35 mm stripe and fullcoat, they could keep somewhat of a grip on it. But when editors started to work on 24-track 2” tape, interlocking videotape to timecode, the cracks were starting to widen. It was clear that the technological evolution was going to rewrite who was going to design and cut and rerecord the soundtrack. Union 695 actually walked into my shop a few months later with chains and a padlock, citing that I was in violation of union regs by having a transfer operation, which clearly fell under the 695 union jurisdiction.

I asked them what made them think so. They marched back to my transfer bay (Figure 14.10) and recited union regs that union 700 editors could not do this kind of work. I corrected them by pointing to John Evans, who was my union 695 transfer operator.

The first union man pointed to the left part of the array, where the various signal processing gear was racked. “His union status doesn't allow him to use that gear.”

“He doesn't.” I replied.

“Then who does?!” he snapped back.

“I do.”

The union guy really thought he had me. “Ah-ha! You're an editor, not a Y-1 mixer!” He started to lift his chains.

“Excuse me,” I interrupted. “I know something about the law gentlemen. Corporate law transcends union law in this case. I am the corporate owner, and as a corporate owner I can do any damn thing I want to. If I want to be a director of cinematography on a show I might produce, I can do that and the union cannot do one thing to stop me.” I pointed to John Evans. “You see, only he uses his side of the rack; when the signal processing gear is utilized, I am the one who does that.”

Figure 14.10 David Yewdall's transfer bay, designed and built by John Mosley.

I noticed that the second union man had drifted back and grabbed the phone, I suppose to call the main office. He came back and tapped his buddy on the arm—they needed to leave.

A couple of days later the two men returned (without chains and a padlock), and asked if I would like a Y-1 union card. “Gee, why didn't you ask me that before?”

More and more of my colleagues were going through this process, carrying dual union cards. Alan Splet is a perfect example. Alan was David Lynch's favorite sound designer, having helmed Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune, and Blue Velvet. On Dune, Alan even served as the fourth rerecording mixer on the console with Bill Varney, Gregg Landaker, and Steve Maslow on Stage D at Goldwyn. Alan's work was truly an art form. His eyesight was very poor, I often had to drive him home late at night when the bus route stopped running, but what a pair of ears he had and what an imagination. His work was wonderfully eclectic, supervising and sound designing films such as The Mosquito Coast, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Poet's Society, Mountains of the Moon, Wind, and, of course, the film he won the Academy Award for, Black Stallion.

I remember him literally having a 35 mm transfer machine to his left; he would play his 1/4” sound masters through an array of sound signal equipment to custom transfer each piece of mag film as he needed it. He would break it off, turn on his stool to his Moviola, lace it up, and sync it to picture. This was an extremely rare technique (and often a luxury), but it was the key to his designing the kind of audio events that he wanted. But this kind of trust takes a director and/or producer to back your play.

Then nonlinear editing become the new promise of lower budgets, faster schedules, and better sound. We have already spoken a bunch about the philosophy and collateral cost issues, so I will not rehash that. It scared the bejesus out of hundreds of veteran sound editors, many who felt that they could not make the transition and dropped out of the industry.

For a while it was really only an issue for editors, but it soon became apparent to the rerecording mixers that it was going to affect them in a huge way. Even today, many mixers are scrambling to compete with, learn, and embrace Pro Tools as an end all. Those who thought Pro Tools was just for editing were not understanding the entire process, and now it is here. More and more projects are no longer being mixed at the traditional houses, because these projects are being completely edited, rerecorded, and print-mastered with Pro Tools.

Is it as good as mixing at the traditional stages? I didn't say that. What I think philosophically does not mean a thing. It is a reality of the evolutionary process that big multimillion-dollar rerecording mix stages will only be used for the big pictures, and virtually everything else is going to be done, at least in part, if not totally, through the computer, using software and a control “mix” surface by one- or two-man mixing crews, often by those who supervised and prepared the tracks in the first place.

THINK BIG—CUT TIGHT

Some of the first things you are going to do, in order to capture the Big Sound on a tiny budget, are crash-downs, pre-predubs, all kinds of little maneuvers to streamline how you can cut faster.

In the traditional world I had 10 stereo pairs of sound effects just for a hydraulic door opening for Starship Troopers. When I handled the sound effects for Fortress II, they could not afford a big budget, but they wanted my kind of sound. I agreed to design and cut all the sound effects and backgrounds for the film on a flat fixed fee.

The deal was, you could not hang over my shoulder every day. You can come Friday afternoons after lunch and I will review what I have done. You make your notes and suggestions and then you leave and I will see you a week later.

The other odd request I made in order to close the deal, since I knew how badly they wanted my kind of sound, was that I could use some wine, you know, to help soften the long hours. I had meant it as a joke. But, sure enough, every so often I had deliveries of plenty of Zinfandel sent to my cutting room. Actually, in retrospect, the afternoons were quite. . .creative.

One of the requests that they did ask of me was that they really wanted space doors that had not been heard before. So I designed all the space doors from scratch, but I couldn't end up with dozens of tracks with umpteen elements for these doors every time they would open and close, not on an ultra low-budget job! So I created a concept session: anything and everything that the client may want to audition as a concept sound that was going to have an ongoing influence in the film—from background concepts, to hard effects, laser fire, telemetry, and so on. So I designed the doors in their umpteen elements and, played them for the client on Friday for approval. Then I mixed each door down to one stereo pair, which became part of my sound palette—a term I use meaning the sound kit that is for that particular show.

I will use the same procedure in creating my palette for anything and everything that repeats itself. Gunshot combos, fist punch combos, falls, mechanicals, myriad audio events that I used to lay out dozens of tracks for the sound effect rerecording mixer to meticulously rehearse and mix together in the traditional process, was being done now in sound-effect palettes. Some editors call them “show kits,” especially if they are working on television shows that repeat the basic stuff week after week. Don't reinvent the wheel. Build your kit and make it easier to blaze through the material.

It might take me a week or two to design and build my sound palette, but once built, I could cut through heavy action reels very quickly, with a narrow use of tracks. Instead of needing as many as 200 or 300 tracks for a heavy space opera sequence, I could deliver two, at the most three 24-track sessions, carefully dividing up the audio concepts in the proper groups. This made the final mixing much smoother.

This style of planning also allows you to cut the entire show, not just a few reels of it, as we used to do on major projects with large sound editorial teams.

I have even gotten to the point that I back up every show in its show kit form. I have a whole series of discs of just the Starship Troopers effects palette, which is also why I can retrieve a Pro Tools session icon from a storage disc, load up the Starship Troopers discs, and resurrect any session I made. This sort of thing can come in extremely handy down the road when a studio wants to do some kind of variation edit, director's cut, or what have you. More than once I have been called by a desperate producer who has prayed that I archived my work on his film, as the studio cannot find the elements!

Strange as it might sound, I have had more fun and freedom in sound design working on smaller-budget pictures than huge-budget films that are often burdened with political pressures and crunched schedule demands.

KEEP IT TIGHT—KEEP IT LEAN

The reality of your team is that you will find yourself doing most if not all your own assistant work. Jobs that were originally assigned to the first assistant sound editor are now done by the dialog editor, or the sound effects editor, or the Foley editor (if you can afford to have a Foley editor).

One of the techniques that I very quickly found as a valuable procedure was to have an expert consultant who I could hire on a daily basis. Ultra low-budget jobs are almost always structured on a fixed flat fee, not including the “If” factors. This means that you cannot afford to make a financial mistake by doing work on a bad EDL or wasting time going back to have the OMF reoutputted because picture editorial did not do it right the first time.

The past few years I have been working rather successfully on the three- to four-man crew system. A client will talk to us about a project, and if we like it and feel we can do it within the tight parameters, then we will sit down and discuss exactly what kind of time frame the client will allow, as more time makes it more realistic to be accomplished. If the client insists on too tight a schedule, the client either needs to come up with more money, because he or she has chosen the other set of the triangle (want it good and want it fast), and therefore it cannot be cheap.

If they have to have it cheap, then they have to give you more time, because we already know they want to have it good. Besides, I am not interested in turning out anything but good work, so we can forget that one as an option right off the bat.

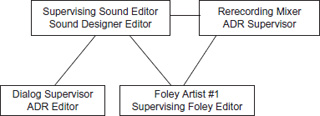

Several projects that I have done lately have been structured in the manner shown in Figure 14.11. It is vital to have a veteran dialog editor—a master at how to structure and smooth the tracks. Though I have cut my share of dialog, I am known for my sound effects design, especially action and concept, so I take on the sound design and sound editing chores for the backgrounds and hard FX. We use a lead Foley artist who also embraces the job of cueing the show as well as performing the action. The budget is a direct reflection of how many days of Foley walking the project can afford. I go over the show notes and make it very clear to the Foley artist exactly what cues we absolutely have to have performed and what cues I can either pull from my library or custom record on our own. This keeps the Foley stage time to the leanest minimum with as little waste as possible.

You notice that I have the rerecording mixer to my side—an equal in the collaboration of developing and carrying out the ultimate rerecording process. On several projects, the rerecording mixer doubled as the ADR supervisor, scheduling the actors to come in and be recorded. The ADR cues, however, are sent back with the stage notes for the dialog editor to include in a separate set of tracks but part of the dialog session. This will yield a dialog session with probably 3 to 4 primary dialog tracks, with 4 to 5 ADR tracks (depending on density), and then the P-FX and X-tracks. This means the dialog session that will be turned over to the rerecording mixer should be 10 to no more than 14 tracks.

The key to really being able to give a big bang for the buck is if you have a powerful customized library. This is where most starting editors have a hard time. Off-the-shelf “prepared” libraries are, for the most part, extremely inferior to those of us who have customized our sound libraries over the past 30 years. I always get a tickle when I have graduate editors, who have frankly gotten spoiled with using my sound effects during their third- and fourth-year films, go out into the world and sooner or later get back to me and tell me how awful the sound libraries are that are out there. Well, it's part of why I push them, as well as you, the reader, to custom record your own sound as much as possible.

Figure 14.11 Typical “ultra low”-budget crew.

Even if you manage to get your hands on a sizable library from somewhere, there is the physicality of “knowing” it. Having a library does not mean anything if you have not auditioned every cue, know every possibility, every strength, every weakness. It takes years to get to know a library, whether you build it yourself or work with a library at another sound house.

You need to spend untold hours going through material, really listening. You see, most people do not know how to really listen. You have to train your ear, you have to be able to discern the slightest differences and detect the edgy fuzziness of oncoming distortion.

I will cut one A session; this will be “Hard FX.” Unlike traditional editing when I break events out into A-FX and B-FX and C-FX and so forth, I will group the controlled event groups together, but they are still in the same session. After all, we do not have all the time in the world to rerecord this soundtrack. Remember, we are making the perception of the Big Sound, not the physical reality of it.

I will cut a second B session. This will be my stereo background pass. Remember my philosophy about backgrounds: dialog will come and go, music cues will come and go, Hard FX will come and go, but backgrounds are heard all the time, even if it is extremely subtle. The stereophonic envelope of the ambience is crucial, and I give it utmost attention.

On ultra low-budget projects like these, I expect 8 Foley tracks will be about as much as we can expect, unless we have to suddenly go to extra tracks for mass activity on the screen. Even then, I do not want to spread too wide.

The best rule of thumb is to prepare the tracks in a way that you yourself could rerecord them the most easily.

RETHINKING THE CREATIVE CONTINUITY

Speaking of intelligently approaching soundtrack design, here is another important consideration—what if you are not preparing it for the rerecording mixer to get his or her arms around? What if, on small budget or even bigger budget projects, the supervising sound editor/sound designer is also serving as the rerecording mixer?

Actually, it makes sense in a big way, if you stop to think about it. Since the advent of the soundtrack for film in 1927, the approach has been a team of sound craftspeople, each doing his or her part of the process. When it reached the rerecording mixing stage, the rerecording mixer had no intimate knowledge of either the preparation or the tactical layout and the whys of how certain tracks were going to work with other tracks or what the editors had prepared that was yet to come to the stage in the form of backgrounds that would serve both as creative ambient statements and/or audio “bandages” to camouflage poor production recording issues. That process was because working on optical sound technology, and even in 1953 when we moved to magnetic stripe/fullcoat film technology, still required a platoon of audio expert craftsmen to record, piece together, and bring the soundtrack to the rerecording stage in the first place, even before it was going to be mixed all together.

Figure 14.12 Mark Mangini, sound designer, supervising sound editor, and rerecording mixer.

However, with today's digital software tools and ever-expanding capacities of storage drive space and faster CPUs, a single sound craftsperson can do the same work that it took 10 or 12 craftspeople to do just a little over a decade ago.

Who better would know the material? Not the rerecording mixer who was not involved with the sound designing process, the editing of that material, and structuring the predub strategies. So, you see, it really makes sense that we are starting to see and are going to see a major move to very tight teams, and in some cases single sound designer/rerecording mixer artists.

One such advocate of this move is Mark Mangini, truly a supervising sound editor/sound designer and rerecording mixer. As a supervising sound editor/sound designer he has worked on feature projects such as Aladdin, Beauty and the Beast, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, Gremlins, Lethal Weapon 4, The Fifth Element, The Green Mile, The Time Machine, and 16 Blocks.

Recently he was troubled by the decision of a producer who shunned the idea of the sound supervisor/sound designer also being the rerecording mixer, as it is the exception and certainly not the norm. Here, then, are the words of Mark Mangini when he decided he needed to write the director and put his thoughts down for the record, thoughts that make a lot of sense—the logic of an inevitable evolution.

On the Importance of Designing and Mixing a Film

A letter from sound designer Mark Mangini to the director of a big-budget studio film:

It is my desire to design, edit, and mix your film. Though the producer and the editor are very well-intentioned in wanting to use the Studio's mix facilities with existing mixers there, they do have some very fine people. I believe that I can bring so much more to the film as the sound designer and mixer, as I have done on your previous projects.

I must state, at the outset, that for a Studio film, this style of working is nontraditional and, as such, will encounter some amount of resistance from your fellow filmmakers accustomed to working in traditional ways (designers only design, editors only edit, and mixers only mix).

This way of working is nontraditional because of the natural and historical compartmentalization of job responsibilities in every aspect of filmmaking, not just sound. As such, very few individuals have taken the time or had the incentive, like myself, to develop natural outgrowths of their skill-set and be proficient in multiple disciplines.

I am certainly not the first to work this way. Walter Murch, Gary Rydstrom, Ben Burtt, to name a few, come to mind and have all been championing the benefits of the sound designer in its broadest interpretation and what that person can bring creatively to a soundtrack. These men have truly been the authors of their respective soundtracks and they are successful at it by virtue of being responsible for and creatively active in all aspects of sound for their films. This does not simply include being the sound editor and the rerecording mixer, but encompasses every aspect of sound production including production sound, ADR, Foley, score recording, sound design, editing, and mixing.

As you have seen in our past work relationship, I have performed in exactly this fashion and I hope that you have recognized the benefits of having one individual whom you can turn to creatively and technically to insure the highest quality soundtrack possible in all the disciplines. This is the way I work and want to continue to work with you.

Though it may appear that this workflow was necessitated by budget (or lack thereof) on our previous films, it was and is, in fact, a premeditated approach that I believe is the most creative and efficient way of working. Just imagine how far we can take this concept with the resources that the Studio is offering.

Unfortunately, Hollywood has not cottoned-on to this approach in the way that Bay Area filmmakers have. We still want to pigeonhole sound people by an antiquated set of job descriptions that fly in the face of modern technology and advancement. It is certainly not rare or unheard of in the production community to see hyphenate “creatives” that write and direct, that act and produce, etc. It is no different in sound. I am simply one of a small group of sound fanatics that wants to work in multiple disciplines and have spent a good deal of time developing the technical acumen in each one.

As such, regarding making “all the super-cool decisions that will give me the most creatively and technically, etc. . . .” I have no doubts that this is the way to do it. There are decided creative, technical, and financial advantages to working this way. This work method is not, in fact, all that unusual for the Studio or the mix room we anticipate using. There have been numerous films that have mixed there that are working in this exact same fashion. New, yes, but not unheard of.

As we spoke of on the phone, I will be working side by side with you, building the track together in a design/mix room adjacent to picture editorial. In the workflow that I am proposing, this is a very natural and efficient process of refinement all the way through to the final mix that is predicated on my ability to mix the track we have been building together and on doing it at the Studio's dubstage, which uses state-of-the-art technology not found in any of the other mix rooms on the lot (and with traditional mixers that are not versed in how to use it).

The value of having the sound design team behind the console cannot be overestimated. It seems to me almost self-evident that having the individuals who designed and edited the material at the console will bring the most informed approach by virtue of an intimate knowledge of every perforation of sound present at the console and the reasons why those sounds are there. This is a natural outgrowth of the collaboration process that we will share in during our exploratory phase of work as we build the track together prior to the mix.

There will be the obvious and natural objections from less forward-thinking individuals who will state that having the sound editors mix their own material is asking for trouble. “They'll mix the sound effects too loud” or “They won't play the score” are many of the uninformed refrains that you might hear as objections to working in this fashion.

I would like to think that, based on our previous work together, you might immediately dispel these concerns having seen, first-hand, how I work, but there is also an issue of professionalism involved that is never considered: This is what I do for a living. I cannot afford to alienate any filmmaker with ham-fisted or self-interest driven mixing.

I consider you a good friend and colleague. As such, I think you know that I am saying this from a desire to make your film sound as great as I possibly can. It's the ones that think outside the box that do reinvent the wheel.

Sincerely,

Mark Mangini, sound designer/supervising sound editor/rerecording mixer

(Note: This is a letter I wrote to a director, regarding a big-budget studio film I was keen on doing. I have modified the original text to make the ideas and comments non-project specific and more universal. MM)

DON'T FORGET THE M&E

Just because you are tackling an ultra low-budget project does not mean that you do not have to worry about the inventory that has to be turned over just as in any film, multimillion dollar or $50,000. The truth of the matter is, passing Q.C. (quality control) and an approved M&E is, in many ways, more difficult to accomplish on ultra low-budget films than on big-budget films, for the simple fact that you do not have extra money and/or manpower to throw at the problem.

It therefore behooves you to have a veteran dialog editor who is a master of preparing P-FX tracks as he or she goes along. (We will talk about this more in Chapter 15.)

These days, you really have to watch how much coverage you have in Foley. For some reason, the studios and distributors have gone crazy, demanding over-Foley performing of material. I mean stupid cues like footsteps across the street that you would never hear; the track can be written up for missing footsteps. I have heard some pretty interesting horror stories, and frankly, I do not know why. I assume it is an ignorance factor somewhere up the line. When in doubt—cover it.

AN EXAMPLE OF ULTRA LOW-BUDGET PROBLEM SOLVING

Just because you do not have a budget does not mean that you cannot problem solve how to achieve superior results. I recently received an email from a young man, Tom Knight, who was just finishing an ultra low-budget film in England. The project was shot in and around London. I was impressed that the lack of a budget did not inhibit the team's dedication to achieve the best audio track that they could record during a challenging production environment, as well as the postproduction process. Tom submitted some details on the project and their approach to problem solve some of the audio hurdles:

Figure 14.13 This setup was for recording an impulse response for a convolution reverb (London, England). Equipment: Mac iBook running Pro Tools LE, M-Box, Technics amp, Alesis Monitor One MKII, AKG 414. Photo by Tom Knight.

The film is titled Car-Jack, an original production, written, produced, and directed by George Swift. I was responsible for all the audio production within the film including original music, location recording, postproduction, and mixing.

George approached me about the film because I had previously worked for him on a short animation the previous year. We were both studying for BAs at the time in our respective subjects and stayed on to study toward Master's degrees.

The 40-minute film about a gang of car-jackers was produced for virtually no budget (less than £1000) even though there was a cast and crew of over 50 people. Everyone worked on the project for free because they believed in the film, which ensured a great spirit on set. We were fortunate enough to have access to the equipment we needed without hire charges from the university (Thames Valley in Ealing, London).

The film was predominantly shot on a Sony Z1 high-def camera and cut digitally using Adobe Premiere. The production audio was recorded onto DAT and cut at my home studio in Pro Tools before being mixed in the pro studios at Uni.

When we filmed indoor locations, I made sure that I went equipped with a laptop (including M-Box), amp, and speaker so that I could record impulse responses. This process involves playing a sine sweep that covers every frequency from 20 Hz to 20 kHz through a speaker, and recording the outputted signal back onto disk through a microphone.

The original sweep can then be removed from the recorded signal, which leaves the sound of the room or space that the recording was made in. Convolution reverbs like Logic's Space Designer can take an impulse recording and then make a fairly accurate representation of the acoustical space back in the studio. This is ideal if you intend to mix lines of production dialog with lines of ADR, because you need the sounds to have similar acoustic properties, so that they blend together and create the impression that they were recorded at the same time.

Figure 14.14 Setup for recording the impulse response for a convolution reverb. It's the same process as above but from the reverse. This part of the room was where the main gang boss character conducted his meetings so it made sense to take the impulse from here. Photo by Tom Knight.

Figure 14.15 shows us setting up the shot before we go for a take. If you look closely under the actress's left hand you can see some tape on the wall. This is where the DPA mic is positioned. The reason it is positioned there is because Heathrow airport is only two miles away and that particular day the planes were taking off straight toward us, and then alternately banking either left or right as you see this picture. Placing it there (rather than on the jacket of the actor) meant that the wall shielded it to some extent from planes that banked left which were heavily picked up by the shotgun.

If the planes banked right then the DPA was wiped out but the shotgun survived due to its directivity. The planes literally take off every 30 seconds from Heathrow so there was no chance of any clean production audio. It was just a case of gathering the best production audio possible to facilitate ADR later on.

To me, this is a classic example of how understanding the disciplines of the art form, and, as we discussed in Chapter 4, “Success or Failure: Before the Camera Even Rolls” this clearly demonstrates the issue of planning for success, rather than what we see all too often of fixing in post what was not properly thought out and prepared for before the cameras even rolled. Thank you Ted for contacting me and submitting this excellent example just in the nick of time to be included in this chapter.

Figure 14.15 Rooftop scene from the film (London, England). Equipment: Sony Z1 camera shooting in high-def, Audio-Technica AT897 shotgun, and DPA condenser mics running through a Mackie 1202-VLZ mixer onto DAT. Cast and crew (left to right): Annabelle Munro (lead actress), Tony Streeter (lead actor), David Scott (cinematographer), George Swift (director), Tom Knight (boom operator/sound mixer). Photo by Julia Kristofik, makeup artist.

KINI KAY

Born in Norman, Oklahoma, Kini Kay attended the University of Oklahoma, majoring in motion picture production. Kini was inspired by the head of that department, Professor Lt. Col. Charles Nedwin Hockman. Kini decided to move to Los Angeles, since he thought a career in film would start much more quickly there than in Oklahoma. So he decided to move that summer and spend 1 year, which, of course, eventually lasted 20 years.

He worked in production for several years on various movies and commercials in props the, art department, and set building, including the TV series Tales from the Darkside and a variety of feature films including Runaway Train and The Beastmaster.

In his second season working on Tales from the Darkside he became responsible for the entire postproduction sound department, of which he was the only member. That provided a great opportunity for him to learn first-hand all the jobs that post sound encompassed, including sound supervisor, dialog editor, sound effects editor, Foley editor, Foley walker, sound designer, and assistant editor.

That show began the path to many other shows including feature films such as Boogie Nights, Forever Young, The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, Bill and Ted's Bogus Journey, Cyborg, and Friday the 13th Part VII, to name a few.

He worked several years at Cannon Films and even longer with the Academy Award winner Dane Davis (for The Matrix) of Danetracks. In 2005 he moved to Oklahoma to teach and share his acquired knowledge as a professor and is currently teaching at the Oklahoma University. Here he shares some of his teachings:

Sound literally enters your body. Eyes see and interpret reflections; ears can hear from 8 to 10 octaves. Eyes see a frequency range equivalent to one octave; ears measure while eyes estimate. Hearing is first to arrive of all the senses, while you are in the womb. Ears may only get a single split second to interpret a sound event; eyes often have the leisure to scan and rescan many times before formulating an opinion. . . . The ears have it!

Here are a couple of things that came to mind to rant about. . .

A squeak? Yeah a squeak.

What kind of squeak? Any squeak?

Are you sure? Are you sure you don't mind if it's a metal squeak, a wood squeak, a bat squeak, a nail squeak, a mouse squeak, a door squeak, a bed squeak, a balloon squeak, a bellows squeak, a long squeak, a short squeak, a loud squeak, a shrill squeak, a deep squeak, a high squeak, a slow squeak, a fast squeak, a wrench squeak, a faucet squeak, a wheel squeak, a ship squeak, a floor squeak, a chair squeak, or perhaps a wicker chair squeak!?

Or maybe you would rather have a creak instead?

Well I need something that will convey blah, blah, blah in my film! (rants the client)

Oh, I see, you don't want just any squeak. As a matter of fact you don't even want “a” squeak. You want the correct and appropriate squeak!

Figure 14.16 Kini Kay (background) goes over the techniques of recording Foley sound effects with his students at the University of Oklahoma.

Lend me your ears dear readers (I promise to give them back after I'm done). In terms of sound, my friends, “time in” equals “quality out.” The amount of time you audition sound effects cues (either from the sound FX library or custom created on the Foley stage) and the amount of time required for precise cutting are exactly equal to the quality of your work. The only thing more important than spending time on auditions and cutting is spending time on concepts and strategies to budget the time it will take in the audition process and cutting the chosen cues.

That is why you can never, ever, ever get away from the “fast,” “cheap,” “good” triangle and the only way I can think of to cut time corners is with veteran experience!

Why so much time needed to do sound correctly? Well, let's talk about that.

1. |

Finding things or ways to make the sound you are thinking up requires an entirely new way of thinking. One must disjoin familiar dimensions: |

What does a piece of celery have to do with a man's finger? |

|

What does a coconut have to do with a horse? |

|

What does old 1/4” reel-to-reel tape have to do with grass? |

|

What do oval-shaped magnets have to do with locusts? |

|

Things that make the sound you need may have no normal relationship to the sound at all; it's truly a new frontier of logic. |

|

2. |

For every one frame of final film there can be hundreds if not thousands of frames of sound changes. What does that mean? Well, there have been times after many a wee hour of overtime that a sound editor can start to think of all his sound effects as his little friends or even his children if it's really late. So, for example, looking at it that way, how different would it be to have an only child or a stadium full of children? |

For any “little” picture change only one splice may be required of the picture editor and you get to say “bye” to him as he goes home to dinner and you consider how to best do your thousand splices for every one of his. (Moral to this story? A picture change after the movie is “locked” is a huge deal and the picture team always says, “Oh don't worry it's just a little change.” Always get them to agree the picture is locked and written as so in your contract when the picture is turned over to you for sound editorial. Then tell the Picture department, “Of course this section won't apply to you since your picture is truly locked, but since crazier things have happened we have had to put in this exorbitant fee for any picture changes in our contracts, but, luckily that doesn't apply to you! Right?” (Then don't plan, but you can start thinking about that trip to Hawaii!)

Now, admittedly, these days, with CGI and all the elaborate visual effects that take place in a modern film I will grant you that a visual image can be made of many parts, but eye people (and that is mostly who you will deal with) understand the work that goes into the visual and the labor and budget needed, but it is extremely rare, to never, that the same workforce or budget is given to the sound department. Ah, my reader dost thou doubt me? Then do this I say: next big movie you go to, stay to the very end (which you better be doing anyway if you are even the least bit interested in how films are made) then count the CGI people and computer techs and compare that number (better have a calculator handy) to the number of people listed for postsound jobs (you can use your fingers and toes for that figure).

So, what does that mean? That means more time for the fewer, due to lack of understanding from the eye people. It's the triangle again: if you have fewer people than you need (money) then each one must put in more time (that equals fast in the triangle), or if you do get enough people and there isn't the budget then that equals cheap in the triangle, and if you are using cheap labor that equals lack of experience, so remember what I said: the only way to cut a sound-time corner is with experience. So inexperience is the antithesis of saving time, so it equals a ton more time to teach those who are willing but don't have the knowledge, and again we are back to fast in the triangle (time).

Time is a prerequisite to good sound, whether 10 people work 10 hours or 100 people work 1 hour, they both equal 100 man hours. A precise strategy should be worked out at least to determine if 5, 10, 15, or 50 people would be the most efficient use of time, and that will also relate to your budget and the experience of your crew (are more experience and higher rates better for this job, or less experience and cheaper rates?).

So, my advice to all who read this is as follows:

1. |

Make some time (my recipe for time is desire, dedication, and discipline). |

2. |

Get in a dark room. |

3. |

Listen to an entire movie and don't let your eyes in on it at all! |

4. |

Then if you really want to go deep, listen to it again in headphones in the dark. |

You'll be amazed at what you hear, and you might not be quite the same person afterwards. At the very least you will have new insight, both on the project as well as the moral professionalism and honesty of your client and picture editorial counterparts.

Good luck to you.

THE BOTTOM LINE

The bottom line is this. No matter if you are working on a multimillion-dollar blockbuster or you are cutting a wonderful little romantic comedy that was shot for a few thousand dollars on HD, the art form of what we do does not change.

The strategies of how we achieve that art form within the bounds of the budget and schedule change, of course, but not the art form of it. The art form is the same.