CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Distinguish between criminal acts and torts and define negligence, giving the requirements to support a claim of negligence

- Explain what is meant by vicarious liability

- Explain the obligations of property owners to those on their property

- Identify and describe the types of damages that may be awarded to an injured party and explain how each is determined

- Explain the defenses to negligence

- Apply the law of negligence to specific fact situations

- Explain the problems in the tort system and identify the proposals for change

A risk confronting almost every person or business is that of behavior that could result in another person's injury or property damage. The basis of the risk is the liability imposed by law on one responsible for injury or damage to other people or their property. It is a risk that can, and in many instances has, attained catastrophic proportions and one that can materialize at any time. There is no way of estimating the amount of legal liability in advance. It may be a mere thousand dollars or a half-million. It is a risk that has no maximum predictable limit.1 Before we study the role of insurance in protecting the individual from the legal liability hazard, we will examine the hazard itself, with emphasis on the doctrines of negligence that give rise to the liability exposure.

![]()

CRIMINAL AND TORTIOUS BEHAVIOR

![]()

Basically, a person can commit two classes of wrongs: public and private. A public wrong is a violation of one of the laws that govern the relationships of the individual with the rest of society; it is called a crime and is the subject of criminal law. Crimes include a wide range of acts: treason, murder, rape, arson, larceny, trespass, disorderly conduct, assault, vagrancy, and so on. Criminal acts are prosecuted by the state as the moving party (plaintiff) against any citizen for violation of a duty prescribed by statute or common law. They are punishable by fine, imprisonment, or death.

A private wrong, on the other hand, is an infringement of the rights of another individual. A private wrong is called a tort, and the person who commits such a wrong is called a tort feasor. Commission of a tort may give the person whose rights were violated a right of action for damages against the tort feasor. Such an action is called a civil action. Torts may be subdivided into intentional and unintentional. Intentional torts include such infringements on the rights of others as assault and battery, libel, slander, false arrest or imprisonment, trespass, or invasion of privacy. Persons who suffer injury as a result of these intentional torts have the right to sue for damages.2 Unintentional torts result from negligence or carelessness. In these cases, the injured party may be entitled to damages in a civil action even though the tort feasor had no malicious intent as in an intentional tort.

Liability insurance is rarely concerned with the legal penalties resulting from criminal behavior or intentional torts. It is considered against public policy to protect an individual from the consequences of an intentional injury he or she inflicts. Although insurance is available to protect against loss resulting from some intentional torts, most liability policies exclude injury or damage caused deliberately or at the direction of the insured. Liability insurance is concerned primarily with unintentional torts or losses arising from negligence.

![]()

Negligence and Legal Liability

We have determined that legal liability has many causes.3 The most important, and the most significant for insurance, is that of negligence. Although many of the doctrines relating to the law of negligence are found in statutes, its primary development has been through common law. The basic principle of common law is that most people have an obligation to behave as a reasonable and prudent individual would. Failure to behave in this manner constitutes negligence, and if this negligence leads to an injury of another, or to damage of another's property, the negligent party may be held liable for the damage. Legal liability is imposed by the courts when it has been established that all the following occurred:

- There was negligence.

- There was actual damage or loss.

- The negligence was the proximate cause of the damage.

![]()

There Must Be Negligence

The basic concept of our law holds that unless a party is at fault, meaning he or she has unreasonably and unlawfully invaded the rights of another, he or she is not liable.4 The basic question in all cases concerning legal liability must be, Has there been negligence? Negligence is defined as a person's failure to exercise the proper degree of care required by the circumstances.

Who May Be Held Liable? To be held legally negligent, it must be established the individual had a duty to act and he or she failed to act or acted incorrectly. The duty to act is the first of the prerequisites.

At the beginning of this discussion, we stated that “most people have an obligation to behave as a reasonable and prudent individual would.” The question arises, What persons do not have this obligation? Certain classes of individuals and institutions are excepted from the obligation.

Infants To be duty-bound to behave in a reasonable and prudent manner, the individual must be capable of determining what is reasonable. The person must have, in the terms of the law, reached the age of reason. In some states, this has been set by law at seven years of age; in other jurisdictions, the court determines the age at which the individual can distinguish between right and wrong. Whereas children below this age are immune from legal liability, a minor who has attained the age of reason may be held legally liable for his or her own negligent acts.5 Although minors can be held legally liable, the degree of care demanded of a child is often different from that required of an adult.

Mentally Incompetent For obvious reasons, certain mentally incompetent persons are not expected to exercise the care required of the sane. In the eyes of the law, a mentally incompetent person is approximately the same as an infant. However, if it can be shown that the deficient person could have been expected to exercise some degree of care, the courts will hold the individual to that degree of caution.

Government Bodies At common law, sovereign powers can be sued only with their permission. Any government unit that shares in the sovereignty is immune from liability unless it is engaging in proprietary functions. When performing strictly government functions, it is normally immune from liability. This government immunity is based on the old common law maxim that “the king can do no wrong.” The doctrine has been modified by statute and court decision. One of the most important qualifications is the Federal Tort Claims Act,6 which provides that the United States shall be liable for monetary damages to the same extent as a private individual. Government immunity has been modified at the state level in many jurisdictions by similar statutes. Finally, in a growing number of instances, the courts have attempted to find exceptions to the doctrine of government immunity, and some have rejected it entirely.7

Even in those areas where the doctrine has not been abrogated, the immunity does not extend to the employees of the government unit who are acting in their capacity as employees. If Mr. Smith is struck by a city vehicle and the damage is the result of the negligence of the vehicle's driver, the city may not be held liable, but the driver does not enjoy the same immunity.

Charitable Institutions Formerly, the liability exposure of a charitable institution and of a profit-making one differed, but this distinction has disappeared. At one time, the courts were reluctant (and some still are) to hold charitable institutions liable, but the recent trend has been to treat them in the same manner as profit-making institutions.

What Constitutes Negligence? As we noted previously, negligence is defined as the failure of a person to exercise the proper degree of care required by the circumstances. As a rule, the duty to exercise care is owed to anyone who might suffer injuries as a result of a person's breach of duty even if the negligent party could not have foreseen a risk of harm to someone because of the behavior.

One of the major problems is to determine what constitutes correct action in any given situation. To make this determination, the courts apply what is known as the prudent man rule, which seeks to ascertain what would have been a reasonable course of action under the circumstances. The fact that some other course of action might have avoided the accident does not make the individual liable. The negligent person is entitled to have his or her actions judged by this “prudent man standard” rather than hindsight. The judge and jury are not permitted to look back at the situation in light of what happened and judge liability on whether some other course of action would have prevented the accident. The action must be judged by what a reasonable and prudent person, confronted with the same situation, might normally and properly have done.

Since the standard is vague and the variety of circumstances and conditions precludes hard-and-fast rules, in the final analysis whether the duty has been breached will be for a court of law to decide.8 Normally, the burden of proof of negligence is on the injured party. However, there are certain doctrines that impose liability by statute or shift the burden of proof from the injured party to the defendant.

Negligence Per Se In many circumstances, what constitutes the standard of care to be met by an individual is set arbitrarily by statute. For example, speed limits in most states set the rate of speed for driving an automobile. These speed limits amount to the establishment of a rule that no reasonable person should violate. If the law is violated, it is referred to as negligence per se (negligence in itself), and the injured party is relieved of the obligation to prove the speed was unreasonable.

Absolute Liability Under certain circumstances, liability may be imposed because “accidents happen,” and it is imposed whether anyone was at fault. In such cases we have the application of the rule of strict or absolute liability. The injured party will be awarded damages even though what the other person was doing or the manner in which it was done was not legally wrong.

One of the most important examples of absolute liability is employment-related injuries. All the states have enacted workers compensation laws that impose absolute liability on employers for injuries to employees who are covered under the laws. In this sense, there is a departure from the basic laws of negligence in the case of an injured worker because there is no need for the worker to prove the employer's negligence. workers compensation laws, then, represent an exception to the rule that there can be no liability without fault, and the injured worker is entitled to indemnity regardless of the employer's negligence or lack of it.

The second application of the rule of strict liability is with respect to extra hazardous activities. The principle is that one who maintains a dangerous condition on his or her premises, or who engages in an activity that involves a high risk to the person or property of others in spite of all reasonable care, will be strictly liable for the harm it causes. Customary examples are keeping wild animals,9 blasting, explosives manufacture, oil-well drilling, crop spraying by airplane, and water containment.

Res Ipsa Loquitur A significant doctrine in the operation of the law of negligence is that of res ipsa loquitur. This means that “the thing speaks for itself” and is concerned with circumstances and accidents that afford reasonable evidence, in the absence of some specific explanation, that negligence existed. The accident is of a type that normally does not occur without someone's negligence, and the doctrine recognizes the persuasive force of a particular kind of circumstantial evidence. The characteristics of the event constitute an inference or prima facie evidence of negligence. In the operation of the doctrine, the law reverses the burden of proof. When the instrumentality causing the damage was under the exclusive control of the defendant, and the accident would not usually happen in the absence of negligence, the law holds that the accident itself is proof the defendant was negligent. For example, if Mr. Smith walks down the sidewalk and a 2000-pound safe being lowered by a rope falls on him, he is not required to prove the person or persons lowering the safe failed to exercise due care. The fact that the safe fell on him (or that he is 18 inches shorter) is evidence of this. The burden of proof is shifted, and the defendants must prove that care was exercised.

For the doctrine to be applicable, certain conditions are generally required. First, the event must not normally occur in the absence of negligence. Second, the instrumentality causing the injuries must be shown to have been under the defendant's exclusive control. Finally, the injured party must in no manner have contributed to his or her own injuries. The injured party must be free from fault.

![]()

There Must Be Damage or Loss

That carelessness existed is insufficient cause for legal liability. Injury or damage must have been suffered by the party seeking recovery. In most cases, it is easy to prove that injury or damage has occurred, but establishing the amount of damages is often difficult.

The tort may result in two forms of injury to another: property damage and bodily injury. In the case of property damage, the extent of the loss is simple to determine. Generally, it is measured by the monetary loss to the injured party. If, for example, another driver negligently collides with your auto and “totals” it, placing a value on the car is simple. Market or depreciated value is the normal measure. An additional loss could involve the loss of use of your car. If you needed a car in your business and had to rent one, the rental expenses would be included in the damages. The loss of use of property could amount to a large sum if, for example, a large building was destroyed. In some cases, punitive damages (discussed shortly) may be awarded for the damage.

In the case of bodily injury, fixing damages can be more complicated. Bodily injuries may lead to claims for medical expenses, lost income (present and future), disfigurement, pain and suffering, mental anguish, and loss of consortium.10

Three classes of damages may be awarded:

- Special Damages. Special damages are designed to compensate for measurable losses, such as medical expenses and lost income caused by the injury.

- General Damages. General damages compensate the injured party for intangible losses, such as pain and suffering, disfigurement, mental anguish, and loss of consortium. Determination of the amount that should be awarded for these damages is subjective.

- Punitive Damages. Punitive damages are amounts assessed against the negligent party as a punishment when the injury resulted from gross negligence or willful intent. They are intended as punishment and to deter others from similar behavior in the future.

Determining the award for each of these losses is difficult for several reasons. First, although the medical and hospital expenses incurred by an injured party are subject to accurate measurement, an injury that will require expenditures for many years into the future can pose valuation problems at the time damages are determined. The same is true with respect to loss of future earnings. If the injury prevents the victim from working again, the problem becomes one of determining the present value of his or her probable future earnings.

In determining the amounts that should be awarded as general damages, we enter the world of fantasy. What, for example, is the “price” for the pain and suffering and mental anguish over the loss of an arm or leg? The best answer is, The amount an attorney can convince a jury it is worth.

Finally, with respect to punitive damages, there has been considerable litigation in recent years over what constitutes an appropriate amount. In a 1996 ruling, BMW v. Gore, the Supreme Court established three factors to consider in determining a punitive damage award: (1) the reprehensibility of the defendant's misconduct, (2) the disparity between the actual or potential harm suffered by the plaintiff and the punitive damages award, and (3) the difference between the punitive damages awarded and the civil penalties authorized or imposed in comparable cases.11 In 2003, the Supreme Court struck down a $145 million punitive damages award, ruling that it was excessive in relation to the compensatory damages of $2.6 million.12

In another case in 2007, the Court ruled that punitive damages may punish the defendant only for harm done to the person who is suing and not for that harm done to others.13

Collateral Source Rule Damages for bodily injury can be assessed against the negligent party even when the injured person recovers the amount of his or her loss from other sources. A basic principle of common law, the collateral source rule, holds that the damages assessed against a tort feasor should not be reduced by the existence of other sources of recovery available to the injured party, such as insurance or a salary continuation plan provided by an employer. If Y injures X and X has full insurance to compensate for the injury, he or she can still sue Y for the amount of medical expenses and lost income he or she would have incurred had there been no insurance.

![]()

Negligence Must Be the Proximate Cause of the Damage

The negligence must have been the proximate cause of the damage if the injured is to collect. This means there must have been an unbroken chain of events beginning with the negligence and leading to the injury or damage. The negligence must have been the cause without which the accident would not have happened.

The negligent person is usually held to be responsible for the direct consequences of his or her action and for the consequences that follow naturally and directly from the negligent conduct. Even if an intervening force arises, the negligent party may be held responsible for the damage if the intervening force was foreseeable. For example, suppose that Smith decides to burn his leaves but takes no precautions to confine the fire. The wind begins to blow (an intervening cause), and the flying embers set Smith's neighbor's house on fire. The negligence began the direct chain of events, and in spite of the intervening cause, Smith could be held liable. The wind is an intervening cause, but one that Smith should have foreseen and for which he should have provided.14

Vicarious Liability There are circumstances in which one person may become legally liable for the negligent behavior of another person. This type of liability is known as “imputed” or vicarious liability and is based on the common law principle of respondeat superior, “let the master answer.” For example, principals are liable for their agents' negligent acts. Employers are liable for their employees's negligence when they are acting within their capacity as employees. In some instances, vicarious liability is imposed by statute. For example, in many states, a car's owner is held liable for the negligent acts of anyone driving it with his or her permission. This is not liability without negligence; negligence exists, but the negligence of one person makes another person liable.

To illustrate the principle of vicarious liability, assume an employee owns her own automobile, has no automobile liability insurance, and is using the car in her employer's business. Through her negligent driving, she seriously injures a pedestrian. The injured party has a right of action against the employee and the employer, and any judgment would be binding on both.15 If the employee is financially irresponsible, the vicarious liability rule will obligate the employer to pay the damages.

Under English common law, a husband was liable for his wife's torts. This is no longer recognized, and the wife is liable for her own torts. As a rule, parents are not liable for torts committed by their children. Here, again, the child is liable for his or her own carelessness. Although this is true as a basic principle, parents may be held liable for the acts of their children in some circumstances. First, the parent may be held liable if it can be shown that the parent was negligent in supervising the child. For example, if a parent was aware that his child's hobby was breaking picture windows and did not at least tell the child to stop, the courts would probably consider this to be negligence on the parent's part. In the same manner, in allowing a child to possess a dangerous weapon, the parent may be deemed negligent and held liable for any injuries caused by the child with the dangerous weapon.16 As a consequence, it might not be too desirable to give your child a machete or a 16-foot blacksnake whip for a birthday present. In addition, the parents may be held liable under the doctrine of respondeat superior if the child is acting as the parent's agent. Several states have enacted statutes that hold that the child is considered to be acting as the parent's agent when driving the family car. Finally, many states have passed special laws that impose liability on the parents for willful and malicious destruction of property by their children. For example, the legal code in Nebraska reads as follows:

The parents shall be jointly and severally liable for the willful and intentional destruction of real and personal property occasioned by their minor or unemancipated children residing with them, or placed by them under the care of other persons.17

The statutes may impose liability without limit, as in Nebraska, or the vicarious liability of the parent may be subject to a maximum, as in Kansas, where the limit is $300.

Joint-and-Several Liability Instances sometimes occur in which the negligence of two or more parties contributes to the injury or damage. In such cases, the question of who is to be held liable is critical. One of the important doctrines in this area is the concept of joint-and-several liability. A liability is said to be joint and several when the plaintiff obtains a judgment that may be enforced against multiple tort feasors collectively or individually. In effect, this doctrine permits an injured party to recover the entire amount of compensation due for injuries from any tort feasor who is able to pay, regardless of the degree of that party's negligence. If A and B are negligent and C is injured, the doctrine of joint-and-several liability permits C to collect the entire amount of damages from A or B even if A was 98 percent at fault and B was 2 percent at fault. The doctrine has been attacked by critics who argue that it is a manifestation of the “deep pocket” theory of recovery.

More than two-thirds of the states have passed laws since 1986 to abolish or modify the doctrine of joint-and-several liability,18 replacing it with several liability or a system for apportionment of damages based on the degree of fault.

Obligations of Property Owners to Others As a general rule, the occupier of land has the right to do as he or she pleases with that land, but the owner of that property or its occupant has an obligation to persons who come onto it. The degree of care that must be exercised depends on the person's status coming onto the land and on the specific circumstances. Common law generally recognizes four classes of persons with differing degrees of care due them: trespassers, licensees, invitees, and children.19

Trespassers A trespasser is a person who comes onto the property without right and without consent of the owner or occupier. As a rule, the land occupant has no duty to exercise care to protect trespassers on his or her land from injury. Trespassing children (discussed shortly) and “discovered trespassers” are exceptions. Once a trespasser has been discovered, the occupier must exercise ordinary care for the trespasser's safety. Otherwise, the only obligation is to avoid doing the intruder intentional injury.20

Licensees A licensee is a person who comes onto the property with the owner's knowledge or toleration but for no purpose of, or benefit to, the latter. This classification includes door-to-door sales-people, business visitors who have strayed from the part of the premises they were invited or authorized to enter, and perhaps visiting friends and relatives.21 As with trespassers, the property owner must avoid intentional harm to a licensee. In addition, the owner must warn the licensee of, or make safe, conditions or activities posing risk or harm that would not be obvious to a reasonable person coming onto the land. For example, the land occupier has a duty to protect licensees from wild or domestic animals on the premises that he or she knows or should know are dangerous. Therefore, if the family dog has a nasty disposition and has displayed this characteristic previously, the occupier of the premises must take care to protect licensees from this animal, or face strict liability.

If the land occupant knows that persons continuously or habitually trespass on his or her land, then the occupant has a higher degree of responsibility to such persons than to ordinary trespassers. This is based on the principle that if the owner knows that persons are in the habit of trespassing and does nothing to stop it, the toleration gives implied consent to the trespassers' presence, changing their status to licensees. Perhaps the best evidence of this implied consent is a beaten path. The land occupier might overcome the implied consent by posting “no trespassing” signs.

Invitees An invitee is a person who has been invited in or onto the property for some purpose of the owner. If the person coming onto the premises of the land occupier is a business visitor, i.e., an invitee, rather than a licensee, the degree of care required of the land occupier increases. Invitees, as a classification, include customers and any person on premises open for admission to the general public, free or paid, such as theaters, churches, railroad stations, and the like. It also includes letter carriers, delivery people, workers, garbage collectors, and similar persons, who come onto the land to further the use to which the land occupier is putting the premises. With respect to invitees, the person occupying the land has a duty to inspect and discover the presence of natural and artificial conditions or activities carrying any risk of harm, and should exercise due care to warn invitees of such dangers or make them safe. This is a more onerous burden than the care one is obligated to exercise with respect to licensees since it applies to more than extraordinary or unusual hazards. Any condition that could cause harm to an invitee is a possible source of legal liability.

Children The law imposes a greater responsibility in the degree of care that must be exercised with regard to children. Children do not always act prudently. This being the case, the law requires the property owner to protect children from themselves, regardless of their status as trespassers, licensees, or guests. Under the doctrine of an attractive nuisance, a high degree of care is imposed on the land occupier for certain conditions on the land, attractive nuisances, that might attract and injure a child of tender years. The doctrine is based on the principle that there is a greater social interest in children's safety than in the land occupier's right to do as he or she pleases with the land. For the doctrine to be applicable, the child must be so immature as to be unable to recognize the danger involved. Or it must be something the land occupant would realize could involve an unreasonable risk of harm to such children.22

In the doctrine's application, the land occupier is obligated to use due care to discover children on the property. If he or she discovers them or is charged with such knowledge, then the occupant is bound to warn them or to protect them from conditions threatening death or serious bodily harm. Many types of artificial conditions have been held to be attractive nuisances. However, there does not appear to be any consistent criterion the courts have utilized. Unattended vehicles have been considered in this category. Explosives, guns, window wells in basements, trees, construction machinery, and fences have all been held to qualify. In fact, almost anything in or about premises has at one time or another been considered as qualifying. It is difficult to eliminate the possibility of legal liability from an attractive nuisance even by dying because even gravestones have qualified under the doctrine.

![]()

Defenses to Negligence

Thus far in our discussion of negligence, we have been concerned with the existence of a duty owed to others and a breach of that duty. But an individual's negligent behavior does not necessarily mean a person has a legal liability. For many torts predicated on negligence alone, the presumed negligent parties may have certain defenses that could free them from legal liability in spite of the negligent behavior.

Assumption of Risk An excellent defense to tort actions is that of assumption of risk by the injured party. If one recognizes and understands the danger involved in an activity and voluntarily chooses to encounter it, this assumption of the risk will bar any recovery for injury caused by negligence. Perhaps the most common application of this doctrine is attendance at certain types of sporting events, such as baseball and hockey. Courts have held that in seeking admission, a spectator must be taken to have chosen to undergo the well-known risk of having his or her face smashed by a baseball or a hockey puck. Another common example is the guest passenger in an automobile. If the car is driven in a grossly negligent manner and the guest fails to protest the dangerous driving, he or she may be considered to have assumed the risk of injury.

Negligence on the Part of the Injured Party Negligence on the part of the injured party may serve as a bar to recovery or, in some jurisdictions, reduce the amount to which the injured party is entitled as damages. Two doctrines have developed: contributory negligence and comparative negligence.

Contributory Negligence As an outgrowth of the idea that every person has an obligation to look out for his or her own safety and cannot blame someone else for damage where personal negligence is to blame, the common law principle of contributory negligence developed.23 To collect, the injured party must come into a court with clean hands. Under the doctrine of contributory negligence, any negligence on the part of the injured party, even though slight, will normally defeat the claim. The degree of contributory negligence is of no consequence. Its existence on the part of the injured party, even though slight, will defeat the claim.

Contributory negligence is an important and effective defense, but it is a harsh doctrine to apply in modern society. It seems unfortunate that some courts continue to follow the common law maxim of refusal to apportion blame. For example, one could seriously question the virtue of a legal doctrine under which a person who is 90 percent to blame for an accident should be free of liability because the injured party was 10 percent responsible.24

The number of instances in which contributory negligence has qualified as a defense can be infinite. One of the most common examples in automobile liability is jaywalking. Failure to signal a turn could be contributory negligence on your part even though your car was rear-ended by an oncoming automobile. Being drunk, running down poorly lighted stairs, teasing an animal, and horseplay have all qualified, to name a few examples of contributory negligence.

Comparative Negligence Because of the harshness of the contributory negligence doctrine, the majority of the states have adopted a somewhat more lenient doctrine, that of comparative negligence. Here, contributory negligence on the part of the injured party will not necessarily defeat the claim but will be used in some manner to mitigate the damages payable by the other party. Comparative negligence rules divide into two broad types. One is the so-called pure rule, sometimes called the Mississippi rule because it was first adopted by that state in 1910. Under this rule, any defendant who is only partly at fault must still pay in proportion to his or her blame.25 Most other states follow the Wisconsin rule, first asserted in 1933, under which the defendant who was least at fault is not required to pay at all.26 By 2007, all but four states had adopted one or the other of these rules.

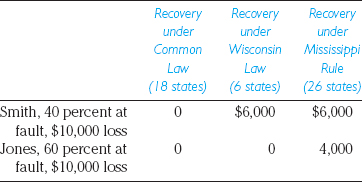

To illustrate the difference between the two approaches, and to provide a contrast with the common law principle of contributory negligence, assume that Smith and Jones are injured in an accident, each suffering losses in the amount of $10,000. Assume Smith is 40 percent and Jones 60 percent at fault. Recovery under each of the systems would be as indicated by the following table.

The comparative negligence principle has much to commend it. It has the effect of tempering the harshness of the contributory negligence doctrine, particularly in situations in which only a slight degree of contributory negligence will defeat an injured party's claim. It seems unfair to disallow a claim in cases in which the negligence of the injured party is slight, but it seems illogical to allow one to recover complete damages in such instances. If the jury can separate degrees of negligence, the comparative negligence principle will produce logical and fair results.

Last Clear Chance The doctrine of last clear chance is an additional modification of the doctrine of contributory negligence. Under this tenet, as utilized in most legal jurisdictions, the injured party's contributory negligence will not bar his or her recovery if the other party immediately prior to the accident had a “last clear chance” to prevent it but failed to seize that chance. Its logic is obvious. If one can avoid an accident and does nothing to prevent its occurrence, one should be legally liable for damages regardless of the injured party's contributory negligence. To illustrate the doctrine, assume X drives onto a highway after stopping at a stop sign. He gets partially onto the highway, when his auto-mobile stalls. He tries frantically to get the car started, but to no avail. A car driven by Ms. Y is speeding down the highway. Although Y notices X's car in advance of the accident, she slows down little and makes no attempt to drive to the other side of the road. From the resulting collision, X may be entitled to collect a considerable amount in damages even though he had no right to be on the highway and even though he knew that his car was in the habit of stalling. Here, Y was negligent because of her failure to use reasonable care in driving her car. She saw X's predicament and could have avoided the accident by slowing down or, if necessary, by coming to a halt. She could also have driven to the other side of the road if it had been clear of oncoming traffic. One of the most difficult lessons for a driver to learn is that having the right-of-way does not mean that one is permitted to use this right without reasonable regard for the safety of others even though the others have placed themselves negligently in situations that may imperil their persons or property.

Survival of Tort Actions Under common law, tort actions do not survive the death of the person committing the injury or the person injured. This prevents any recovery by the deceased individual's estate or personal representative. The responsible person could be held criminally but not civilly responsible. This rule had the unusual characteristic of making it more profitable to kill a person than to maim him or her. In almost every jurisdiction, this rule has been changed to some extent. Some statutes declare that cause of action for damage to property survives the death of the plaintiff or the defendant. But most go further and allow the survival of causes of action for personal injuries.

Every jurisdiction has some sort of statute of wrongful death. The most common creates a new cause of action for the benefit of particular surviving relatives (usually the spouse, children, or parents) that permits the recovery of the damage sustained by such persons. The new cause of action, however, does not eliminate any defenses available to the responsible party. Thus, the decedent's contributory negligence, risk assumption, or a release executed by him or her before death for the full recovery of a judgment by the deceased are all held to bar wrongful death actions in most states.

Legal Liability and Bankruptcy The risk of legal liability is one fraught with potential catastrophic losses. With all the various factors used in determining damages in an action for negligence added together, the result could be astounding. Naturally, the question must arise as to whether the guilty party, confronted with a large judgment, has any alternative but to pay even if it takes the balance of his or her lifetime to make complete settlement. Bankruptcy is, of course, an alternative, and perhaps is the only possible course of action. The negligent party will lose most of what he or she has accumulated up to this point in life but will be released from the judgment's balance. The discharge of the judgment may appear to be desirable to the guilty party, but the stigma of bankruptcy will be lifelong and will hamper practically all his or her future business and personal activities.

A judgment for liability arising from a willful or malicious tort, on the other hand, cannot be discharged by bankruptcy. The guilty party will be obligated to pay the judgment if it takes the rest of his or her life. That bankruptcy will not discharge a judgment arising from a willful or malicious act should be appreciated, particularly by young people who are inclined to drive in a manner that could amount to willful and malicious behavior.

![]()

POSSIBLE CHANGES IN THE TORT SYSTEM

![]()

In the 1980s, a debate over the tort system that had begun with dissatisfaction over the “auto-mobile problem” moved from the auto field into the field of general liability. Initially, agitation for reform came from the medical profession, whose members complained that the costs of insuring against tort losses had become an unbearable burden. Later, manufacturers complained that liability suits involving defective products had reached an unbearable level. The high cost of insuring against liability losses produced what many called a liability insurance crisis, affecting classes as diverse as day care centers, recreational facilities, medical practitioners, architects, product manufacturers, governmental bodies, and the officers of major corporations. Dissatisfaction with the system reached a peak in the period from 1985 to 1987, when many buyers faced astronomical increases for liability insurance, which the insurance industry blamed on a tort system out of control. Pressure for reform came from a coalition of insurance buyers and the insurance industry. Opposition to reform has come principally from the American Trial Lawyers Association and other groups representing the plaintiff's bar.

The seven changes in the tort system that are collectively considered to be tort reform include the following:

- Alternative dispute resolution mechanisms, such as binding arbitration for small claims to reduce the cost of litigation

- Elimination of the doctrine of joint-and-several liability

- Establishing a sliding fee schedule for plaintiffs' attorneys in place of the contingency system

- Limitations or “caps” on awards for non-economic damages (pain and suffering)

- Elimination of the collateral source rule (subtracting from the award for economic damages any reimbursement from other sources, such as personal health insurance)

- Periodic payment of awards (also called structured settlements) in place of lump-sum awards

- Elimination of punitive damages or making punitive damages payable to the state rather than to the injured party

In response to the pressure, most states have enacted some elements of tort reform. In general, however, the impact of reform on liability insurance costs has been modest. The limited impact of the reform measures that have been adopted thus far is blamed on two factors.

First, the reforms were nearly all at the state level, which means their impact would be localized. Those who advocate serious tort reform have always been skeptical that state-by-state reform would solve the problem. In the case of product liability, for example, they point out that we are a national market and only a national system of product liability tort reform will eliminate the problems that underlie the crisis.

Furthermore, because insurers had not maintained loss data in a form that indicates the proportion of liability losses attributable to pain and suffering, punitive damages, or contingency fees, they had difficulty in judging the amount by which the reforms were likely to reduce future losses. As a result, many states enacted legislation requiring insurers to accumulate loss data according to categories that will permit measurement of such factors in the future.

Although the impact of tort reform on insurance prices has not met consumer expectations, evidence shows that the regional changes in the tort system has had a positive effect on insurer losses and on premiums. The limitations on joint-and-several liability, pain and suffering, and punitive damages did reduce insurers' losses, and the reductions were passed on to buyers in the form of premiums that were lower than would have been otherwise.27

Federal Class Action Reform A class action is a lawsuit aimed at a company whose actions have damaged a group of individuals in a similar way. In a class action lawsuit, one individual may represent the entire group and sue on behalf of all individuals the company has harmed. Class action lawsuits are designed for situations in which large numbers of people have cases that involve common questions of law and fact.

Proponents of class action lawsuits argue that they improve efficiency in the legal process and lower the costs of litigation because common issues have to be decided once. They also make it possible to sue when the loss suffered by a single individual is too small to justify the lawsuit costs, but the combined group loss is large enough. Although class action lawsuits can permit efficient claims resolution, they have been subject to criticism. In some class action lawsuits, class members received little or no compensation while the attorneys received large fees. Critics maintain that national class actions are too frequently brought in jurisdictions with a bias toward plaintiffs, where state judges improperly certify a national class even though it does not involve common questions of fact or law. Defendants are then pressured to settle even questionable cases because of the potentially large loss if they lose in litigation. In response to perceived abuses in class action litigation, Congress enacted the Class Action Fairness Act of 2005 (CAFA). The bill was intended to counter two issues. First, CAFA addresses the issue of forum shopping (i.e., plaintiffs seeking a friendly court to hear the case) by providing that certain class action lawsuits may be heard in federal, rather than state, court.28 Second, CAFA requires greater scrutiny of settlements, particularly in the case of coupon settlements.29

![]()

SUMMARY

![]()

Although we have surveyed only the more fundamental aspects of legal liability, the tremendous exposure the individual faces in this area should be evident.30 The catastrophic proportions that the liability loss can assume suggest that the appropriate risk management technique for this exposure is transfer. This is accomplished for the most part by transfer of the risk to an insurance company through the purchase of liability insurance, the subject of Chapter 28.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

tort

intentional torts

unintentional torts

negligence

lex talionis

law of retaliation

sovereign immunity

negligence per se

absolute liability

res ipsa loquitur

scienter

vicious propensity

consortium

proximate cause

special damages

general damages

punitive damages

collateral source rule

vicarious liability

joint-and-several liability

respondeat superior

trespassers

licensees

invitees

attractive nuisance

assumption of risk

contributory negligence

comparative negligence

last clear chance

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. What conditions must exist before an individual may be held legally liable in a tort action?

2. Distinguish among invitee, licensee, and trespasser, and describe a property owner's responsibilities to each.

3. Give an example of each of the following legal doctrines: res ipsa loquitur, scienter, and negligence per se.

4. Explain fully what is meant by the term vicarious liability, giving examples of several situations in which vicarious liability is likely to exist.

5. Identify the defenses that may be used against a tort action.

6. To what extent may parents be held liable for the acts of their minor children? Be complete and specific.

7. Distinguish between the concepts of contributory negligence and comparative negligence. Which doctrine is used in your state? Which do you feel is the more reasonable, and why?

8. What factors are considered in determining the amount of damages to which a person who suffers bodily injury is entitled in a tort action?

9. What is meant by the term absolute liability? Give three examples of absolute liability.

10. To what extent are the risk management techniques of avoidance, reduction, and retention suitable and adequate techniques for dealing with the liability risk?

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. At one time, it was felt that liability insurance would undermine the tort system, which has as its central theorem the concept that the individual responsible for injuring another should be made to pay for that injury. Do you think the existence of liability insurance causes one to be less careful than he or she might otherwise be?

2. Schwartz had been troubled by burglars, so he installed a trap in his building with a shotgun rigged to fire when an intruder opened the door. Sam Burglar broke into the building and lost both legs when the shotgun discharged. Sam thereupon brought suit against Schwartz for damages. What defenses might Schwartz offer? Do you believe that a court would permit recovery under such circumstances?

3. Bodily injury awards have increased at a significant rate during the past two decades. To what do you attribute this increase? Were previous awards inadequate, or are the current ones excessive?

4. Because of a rash of liability suits and high judgments, many municipalities and government subdivisions have had difficulty in obtaining liability insurance for a decade. This seems ironic considering that a short time ago, such entities were immune from liability. To what do you attribute the reversal?

5. What major liability exposures do you as an individual in your current status as a student face? How are your exposures likely to change after you have completed your education?

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Altschuler, Bruce E., Celia A. Sgroi, and Margaret Ryniker. Understanding Law in a Changing Society 3rd ed. Paradigm Publishers, 2005.

Baker, Tom. The Medical Malpractice Myth. University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Danzon, Patricia M. “Tort Reform: The Role of Government in Private Insurance Markets.” Journal of Legal Studies 13(3). University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Kessler, Dennis B. “Evaluating the Medical Malpractice System and Options for Reform.” J Econ Perspect. 25(2), Spring 2011.

O'Connell, Jeffery O. and Christopher J. Robinette. A Recipe For Balanced Tort Reform: Early Offers with Swift Settlements. Carolina Academic Press, 2008.

Prosser, William L., John W. Wade, Victor E. Schwarz, Kathryn Kelly, and David F. Partlett. Cases and Materials on Torts, 12th ed. Foundation Press, 2010.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| American Association for Justice (formerly American Trial Lawyers Association) | www.justice.org |

| American Tort Reform Association | www.atra.org |

| Best's Review | www.bestreview.com |

| Business Insurance | www.businessinsurance.com |

| Information Information Institute | www.iii.org |

![]()

1For many risks, the maximum predictable loss can be calculated. For example, owning a car entails the possibility of the loss of the automobile's value, a loss with a maximum limit equal to the car's value. But with respect to the legal liability arising from driving it, the loss will depend on the accident severity and the amount the jury is willing to award the injured parties.

2It is possible for an act to be a crime and a tort. If Smith assaults Jones, he commits a crime and he may go to jail, but in addition if he has committed a tort, he may be liable for civil damages if Jones decides to sue.

3Liability may arise from contracts. Civil law is composed of two branches: the law of contracts and the law of torts. Here we are concerned primarily with torts.

4The concept of tort liability grew out of the ancient and deeprooted lex talionis: the law of retaliation. Originally, absolute liability was the rule, and it was harshly applied. If a stone fell from a building and killed an occupant, the builder was put to death. Later, making the builder support the dead man's widow instead of killing him made more sense, and the idea of compensation developed. Gradually, the courts shifted away from the concept of absolute liability, under which liability was imposed regardless of fault, to the doctrine of negligence, under which a person cannot be held responsible unless proven negligent or at fault.

5In addition to confusion over the liability of children, the liability of parents for their children's acts is often misunderstood. Fundamentally, parents are not liable for their children's acts. This point will be discussed in greater detail later in the chapter.

6Title 28, United States Code, Sections 1346(b), 2401, and 2671–2680.

7States in which government immunity has been substantially affected by statute include Alaska, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, and Washington. The doctrine has been judicially invalidated in the states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Indiana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. In some states, the immunity is waived if insurance is in effect; these include Georgia, Maine, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, and Tennessee.

8Not all situations arising from negligence become subjects of court litigation, particularly those in which insurance is involved. Adjusters can determine the existence or nonexistence of legal liability in the vast majority of cases without court action. Only those in which the facts or issues are debatable reach court, and these constitute a small percentage of the total.

9Pets represent a separate case. Up until a few years ago, most states still operated under the English common law doctrine that permitted a dog “one free bite.” According to the doctrine of scienter (knowledge), the owner of the animal is liable for the injuries caused by the animal only if the animal is known to be vicious. Hence, one “free bite.” How could the owner know the dog would bite people until it has bitten one? Recently, however, this doctrine has been changed in most jurisdictions. The prevailing current rule holds that anyone who keeps a pet he or she knows or should know to be dangerous can be held strictly liable for any injuries caused by the animal. This doctrine of the owner's liability is known as the doctrine of vicious propensity.

10Loss of consortium originally referred to the loss of a wife's companionship. Under a common law rule still retained in most states, a husband has the right to the services and consortium of his wife. A husband has an ancillary cause of action against a negligent party who is responsible for the loss of his wife's services and consortium, as well as for reasonable expenses incurred for her recovery. Originally, loss of consortium applied only to the husband's right to sue for loss of the wife's services, and a wife had no corresponding right vis-à-vis her husband's services, but states now permit damages for loss of consortium by husband or wife.

11BMW of North America, Inc. v. Ira Gore, Jr., No. 94-896 (May 20, 1996). Gore had purchased a new BMW. Subsequently, he discovered that BMW had repainted the car prior to his buying it. At trial, it was discovered that the company had a policy to repair cars damaged during manufacture or transportation if the amount of damage did not exceed 3 percent of the car's suggested retail price. The dealer was not advised that any repairs had been made. The jury found BMW liable to Gore for compensatory damages of $4000. In addition, the jury assessed $4 million in punitive damages, which the Alabama Supreme Court later reduced to $2 million. The Supreme Court ruled that the punitive damage award was “grossly excessive” and articulated the three-factor test for reasonable punitive damage awards.

12State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company v. Campbell, No. 01-1289 (April 7, 2003). The case involved a State Farm insured, Campbell, who was sued for his part in an automobile accident. Campbell had only $50,000 in liability insurance limits to cover the accident. State Farm refused to settle within the policy limits, instead taking the case to trial. The trial court awarded the plaintiff $185,849 in damages. State Farm refused to pay the amount in excess of the policy limits, and Campbell sued State Farm for bad faith. In its ruling, the Court held that “few awards exceeding a single-digit ratio between punitive and compensatory damages” will satisfy due process.

13Philip Morris USA v. Williams, Mayola, No. 05-1256 (February 20, 2007). The case involved an individual, Jesse Williams, who died of lung cancer in 1997 at the age of 67. A state court had awarded compensatory damages of $800,000 (later reduced to $500,000) and punitive damages of $79.5 million. The jury imposed the relatively large punitive damage award on the basis that Philip Morris had perpetrated a systemic fraud affecting a large group of individuals over a 50-year period. The Supreme Court threw out the punitive damages award because it was designed to punish Philip Morris for damage done to victims other than Campbell.

14In addition to an intervening cause, the chain of casualty can be interrupted by a “superseding” cause. A superseding cause is one that is more immediate to the event and “replaces” a prior event as the proximate cause. The doctrine of last clear chance discussed later in the chapter is an example of a superseding cause.

15The injured pedestrian will probably sue both or, in legal parlance, “everybody in sight.” The purpose of the doctrine of respondeat superior is to permit the inclusion of other parties who probably will be better able to pay for the injury. Vicarious liability does not relieve the agent of liability. Instead, it makes it possible to impute his or her negligence to additional persons.

16An automobile is not considered a “dangerous weapon” in this context. The subject of legal liability arising out of the ownership and use of automobiles will be discussed in Chapter 28.

17Section 43–801, Revised Statutes of Nebraska, Reissue of 1960. Unemancipated means that the child is not freed; an emancipated child is one who has left home and is self-supporting.

18Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

19The once firmly established distinction among trespassers, licensees, and invitees has been modified by the courts in some jurisdictions. For example, courts in California and Hawaii have abolished the distinction. See W. Page Keeton, General Editor, Prosser and Keeton on the Law of Torts, 5th ed. (St. Paul, Minn.: West, 1984), p. 432ff.

20That the person was a trespasser is not a defense for injuries caused intentionally; intentional injury to another is permitted only in self-defense. The rule is that one is privileged to use force likely to cause death or serious bodily harm only if there is reason to believe the other party's behavior would cause one's death or serious bodily harm. For example, if someone were coming at you in an insane frenzy with a meat cleaver in one hand and a double-bitted axe in the other, you would be privileged to defend yourself with force that could inflict serious bodily harm on the other party. In addition, if someone intrudes on your land, you have the privilege to use force unlikely to cause death or serious bodily harm if you have demanded that the intruder leave or desist and the demand has been ignored.

21The situation with respect to social guests varies in different jurisdictions. The majority of the courts hold that a social guest is a licensee although some courts have held that a social guest is an invitee.

22The courts regard the doctrine as an exception to the general rules of negligence or as an application of the rules of negligence to a special class of persons, that is, children. The doctrine, however, is rarely applicable to a child over age 12.

23Contributory negligence is a defense only to tort actions based on negligence. It is not a defense to intentional torts such as assault and battery or to any tort predicated on strict liability.

24Because of the doctrine's obvious and unjust harshness, some courts by judicial interpretation use the rule of comparative negligence discussed next. In practice, many courts are inclined perhaps to ignore slight degrees of contributory negligence.

25States following the pure comparative negligence rule are Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island. South Dakota (for slight negligence only) and Washington.

26States that follow the Wisconsin rule may be divided into two classes: those that permit recovery when the injured party's negligence is less than that of the other person (the 49 percent rule) and those that permit recovery when the injured party's negligence is not greater than the other person's (the 50 percent rule). States that follow the less than rule are Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Maine, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Utah, and West Virginia. States following the not greater than rule are Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.

27For a summary of research on this issue, see “The Effects of Tort Reform: Evidence from the States” (Congressional Budget Office, June 2004).

28These include cases in which the combined alleged damages of all class members exceeds $5 million or in which any member of the class is a citizen of a different state than the defendant. The federal court may decline jurisdiction in some cases.

29Under coupon settlements, plaintiffs receive a minimal benefit, such as a coupon for future services or discounts for future services, many of which are unused. These have been criticized for providing little or no compensation to the plaintiffs, whereas attorneys collect large fees. Under CAFA, attorney fees must be based on the value of coupons redeemed. The act requires judicial review of coupon settlements. The court can approve a coupon settlement only after a hearing to determine the settlement is fair, reasonable, and adequate.

30The tort system is an evolving body of legal doctrines. It has undergone significant change in the past and is likely to change. Changes in the tort system as it relates to automobiles are discussed in Chapter 29.