CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

When you have finished this chapter, you should be able to

- Identify the three major decisions that must be made in buying life insurance and the sequence in which the decisions should be made

- Identify the ways in which a consumer can determine the financial strength of a life insurer

- Discuss the relative merits of term insurance and cash value insurance for meeting financial security needs

- Explain how differences in cost among traditional life insurance policies can be compared

- Explain how differences in cost among universal and variable life insurance policies can be compared

- Discuss the deficiencies in the current price disclosure system used in the life insurance field

- Briefly summarize the advantages and disadvantages of life insurance as an investment

The purchase of life insurance differs in many ways from the other purchases that the average consumer makes every day. In many ways, it differs from the purchase of other forms of insurance since it sometimes combines protection with savings. In addition, because of the long-term nature of most life insurance contracts, the decision normally calls for committing funds well into the future to pay for the policy. Such a long-term commitment requires forethought and consideration of objectives. One out of every five life insurance policies purchased is dropped within the first two years of its purchase, and this indicates the consumer regrets sometimes associated with the purchase of life insurance. We turn now to the subject of buying life insurance.

![]()

DECISIONS IN BUYING LIFE INSURANCE

![]()

Three fundamental decisions must be made in the purchase of life insurance:

- How much should I buy?

- What kind should I buy?

- From which company should I buy it?

In Chapter 10, we examined several approaches to answering the first question. Here we are concerned with the remaining two questions. The first and most important question to be addressed in the purchase of life insurance is the amount. Only after this question has been answered should the type of policy to be purchased be addressed.

![]()

Buy Term and Invest the Difference?

Buy term and invest the difference are the six most controversial words in the area of life insurance buying. They summarize the philosophy of those who have argued the individual would be better off by purchasing term insurance and investing, separately, the difference in premiums between term and permanent insurance. The long-raging controversy between the proponents of permanent insurance as an investment and the advocates of insurance for the sake of pure protection will probably never be settled.

If it were not for the risk management process dealing with the risk of outliving one's income, we could ignore the debate over term versus cash value life insurance. But the individual must be concerned with the possibility of living beyond the income-earning years, and recognizing this contingency, must plan to meet it. If one foresees that his or her income will cease in the future while the need for income will remain, the logical course of action is to provide for the accumulation of a fund that can replace the income. Life insurance can be one vehicle for amassing that fund, and we ought, therefore, to discuss the merits of this form of accumulation.

There are, as we have seen, two separate risks that can be met through life insurance: premature death and superannuation. These two risks are diametrically opposed. If the individual dies before reaching retirement age, there is no need to have accumulated a fund for retirement income. On the other hand, if he or she survives to enjoy retirement, the death benefits will have been unnecessary. Unfortunately, from an insurance-buying point of view, we do not know what the future holds, so the individual must prepare for both contingencies.

Many persons do have insufficient income to provide adequate death protection and simultaneously accumulate funds for retirement, forcing a choice between death protection and the savings element. As Table 17.1 indicates, there is an inverse relationship between the amount of insurance protection and the cash value of the various forms of life insurance. The higher the cash value, the lower the amount of death protection that can be purchased for a given number of premium dollars.

TABLE 17.1 Protection and Cash Values Available per $100 in Premium—Nonparticipating Rates

The decision to be made in the purchase of insurance should be divided into three separate and unrelated decisions. First, and this is the most important risk management decision, what should be done about the risk of premature death? How significant is this risk relative to many others the individual faces? Measuring the loss potential here requires determination of the amount of insurance needed. If the potential loss that is beyond the family's margin for contingencies is $250,000 or $500,000, then this is the amount of risk that ought to be transferred to the insurance company.

The first question, then, is not what kind of life insurance should be purchased but, rather, how much is needed. Often, the answer to this first question will provide an answer to the second question, which is the type of insurance that should be purchased. If the amount of insurance needed is substantial, term insurance may be the only alternative. When the money available for life insurance is limited (and it usually is), the savings feature of permanent insurance forces the individual into a compromise in setting up protection for the family during the critical years. If one follows the proper techniques of risk management, one will seek to transfer that portion of the risk of loss of income-earning ability that his or her family could not afford to bear. If sufficient insurance is purchased to replace the income that would be lost, term insurance may be all that the individual can afford. In other words, as we have seen from our programming example, the arguments about term versus other forms of life insurance are meaningless for a substantial portion of the population because with limited resources to spend on insurance, there may be very little “difference” left after providing for complete protection.

In the cold realism of mathematics, we noted that the insurable value of a young man earning $30,000 a year might be as much as $300,000 or more. If this individual chooses to purchase cash value coverage for this amount, the premiums would be more than $3000 a year. Even based on the needs approach, we saw that significant amounts of insurance may be required. The buyer opting for permanent life insurance must make a choice between savings and protection. This is not intended as a criticism of cash value life insurance. It is a criticism of the misuse of cash value life insurance and the violations of good risk management practice that it entails. In fact, the major criticism that can be levied against cash value life insurance is that it frequently leads to a violation of all three rules of risk management. With a limited number of dollars available for the purchase of life insurance, cash value life insurance carries an opportunity cost in the death protection that must be forgone. As a result, many individuals leave their families inadequately protected. They fail to consider the odds by purchasing coverage against an event that is not a contingency, and in so doing, they risk more than their family can afford to lose. They risk a lot for a little by underinsuring their income-earning ability, leaving a serious exposure unprotected in exchange for interest on the funds that should have been used to protect against that exposure.1 They commit the great error of permitting the question of the type of policy to purchase to determine the amount to purchase instead of vice versa. The first and most important decision is the amount of protection needed, a decision that must be made without reference to the type of coverage that will be obtained to provide the protection.

In deciding on the form of life insurance to be purchased, we leave the area of risk management and enter the field of finance. The question of term insurance versus permanent cash value insurance is a separate issue, unrelated to the problems of risk management. Once the individual has decided to transfer the risk of the loss of $100,000 or $200,000 in income-earning ability to an insurance company, the rules and principles of risk management are no longer helpful. The choice of the type of insurance contract to be used is an investment question and should be evaluated by the same standards used in ranking investments of other types. In fact, the question is not one of term versus permanent insurance at all but a choice between permanent insurance and alternative forms of investment. The only logical reason for the purchase of cash value insurance is that it is superior to the other investment alternatives available to the insured for his or her purpose.2

Sometimes, the purveyors of life insurance attempt to pose the choice between term and permanent insurance in terms of protection rather than an investment decision by pointing out that term insurance cannot be continued beyond age 65 or 70. “Term insurance is only temporary protection,” they criticize as if something were inherently good about insurance that is not temporary. Since the income-earning period and the economic life value of an individual are temporary, it is permanent that takes on the undesirable connotation. By age 65, a person's economic value has declined to zero in most cases; in addition, by this time the economic responsibility to dependents is also normally fulfilled. One has little need for income earning protection at this age; yet it is during the 35-year period following this age that the cost of life insurance becomes prohibitive. Nothing could more be a violation of the principles of risk management than insuring an asset that no longer has value.3

![]()

Life Insurance as an Investment

The long-raging controversy between the proponents of permanent insurance as an investment and the advocates of insurance for the sake of pure protection will probably never be settled. A considerable amount of literature—much of it generated by vendors of competing investments—condemns life insurance as an investment. The issue, however, is more complex than this literature suggests, and anyone who states that “life insurance is a poor investment” is oversimplifying the issue. In fact, the assertion that any investment is good or poor rests on unstated assumptions that may or may not hold true for various of circumstances. There are some situations in which life insurance may compare favorably with other investment alternatives, and the student should be aware of these situations.

The first feature often cited in support of life insurance as an investment is the compulsion it entails. Many people do not have the self-discipline and determination required to follow through with their plans for the regular accumulation of a savings fund. Once a policy is taken out, an individual usually will pay the premiums rather than deprive the family of the protection the policy gives, and paying the premiums means making regular contributions to the savings element of the contract. Frankly, this argument is not compelling.

A more persuasive advantage of life insurance as an investment is that it enjoys certain tax advantages other forms of investment do not enjoy. First, increments in the cash value are not taxable until received by the insured. At the time the policy is surrendered, the excess of the cash surrender value over the premiums paid is taxable as ordinary income. Furthermore, the insured is permitted to deduct the total amount of premiums paid, which includes the cost of protection in computing the gain. The advantage of the tax deferral lies with the individual's tax rate possibly being lower when the gain is eventually taxed and, more important, that the accumulation of untaxed earnings will be greater than the accumulation of taxed earnings. To earn a net return on investments that do not share the tax advantage enjoyed by life insurance, the gross rate of return on the alternative investment must be higher than available under the life contract.

Finally, a safety of principal is not found in certain other investments. The major criticism usually leveled at life insurance as an investment is the relatively low rate of return, usually between 6 and 8 percent (sometimes lower, depending on the company). Perhaps the rate of return is low, but low relative to what? Common stocks represent a riskier form of investment. The investor hopes to realize gains but may suffer losses. Traditional life insurance cash values are a guaranteed form of investment, with safety of principal and a guaranteed minimum rate of return.4 In addition, the newer interest-sensitive policies make it possible to realize higher returns than those guaranteed in the policy. Finally, for the investor who prefers the appreciation potential of common stocks, variable life insurance offers the same tax deferral as traditional cash value life insurance.

With respect to the return on life insurance policies, it should be noted that life insurance policies have a relatively high expense component. For many forms of life insurance, the front-end commission makes the return during the early years negative and, in the long run, less attractive than alternative investments. The actual rate of return to be earned on the investment element, then, depends on the time for which the policy is maintained. If it is to be considered as an investment, life insurance should be considered only as a long-term investment.

Besides the expense factor, another legitimate criticism of traditional life insurance as an investment is that inflation may erode the value of the contribution, but this is a legitimate criticism of all fixed-dollar instruments. When one makes judgments about the “goodness” or “badness” of a given investment type, an implicit assumption exists about future economic trends. If the future economy is marked by inflation and a rising price level, then traditional cash value life insurance (or any other fixed-dollar investment) will be less attractive than those investments that ride the inflationary trend.

The most appealing feature of life insurance as an investment is its complementary functions of providing protection against premature death at the same time it provides an accumulation that may be used if the individual does not die prematurely. If the individual has no need for protection against premature death, life insurance will probably not match other investment alternatives. At the risk of oversimplification, the premium for cash value life insurance covers three things: The first part goes to pay the death benefits for those group members who die, the second part goes to pay the insurer's operating expenses (including agents' commissions), and the third part contributes to the accumulating savings element. The individual who has no need for death protection but purchases life insurance as an investment incurs costs for death benefits and commissions avoided with other investments. To the extent that life insurance is an attractive investment, its appeal is based primarily on its role in meeting the diametrically opposed risks of premature death and superannuation.

For many individuals, traditional cash value life insurance may be an attractive and dependable investment. However, there are many individuals who are not content with the fixed-dollar nature of traditional life insurance, preferring equity investments with their potentially greater return. The choice, however, is a matter of finance rather than of insurance.

![]()

Choosing the Company

In choosing from among the approximately 1,000 life insurance companies doing business in the United States, the insurance buyer may consider many factors, some more important than others. Among the weightier considerations are the company's financial strength and integrity, its policy forms and their suitability to the insured's needs, and the cost.

Financial Strength and Integrity Since the life insurance policy represents a long-term promise on the part of the seller, the financial strength of the insurer and its ability to meet its promise rank as the first consideration. Although consumers have generally taken the financial strength of life insurers for granted, this changed dramatically in 1991 when several large life insurers encountered financial difficulties. Throughout much of 1990, industry observers had warned that many life insurers were in a perilous condition. In April 1991, the California insurance commissioner seized the Executive Life Insurance Company, triggering speculation about the financial condition of other life insurers. The seizure sensitized consumers to the risk of life insurer insolvencies and, as policyholders lost confidence, caused policyholder runs on other life insurers. The seizure of Executive Life was followed by the failure of First Capital Life, Fidelity Bankers Life,5 and Monarch Life Insurance. Then, in July 1991, Mutual Benefit Life Insurance Company of Newark, New Jersey, the 18th largest life insurer in the country, with $13.8 billion in assets, submitted to the control of the New Jersey insurance department.

The financial problems afflicting life insurers in the early 1990s resulted from three causes. The first was a decline in the insurers' bond portfolio value. The second was the almost simultaneous souring of mortgage loans held by some insurers. The third factor was disintermediation, that is the “run on the bank”, which exacerbated the problems created by the first two.6

Many authorities argue that the difficulties encountered by some life insurers can be traced to the introduction of universal life and other interest-sensitive policies, which were sold on the basis of their return rates. Insurers developed universal life (UL) and other interest-sensitive policies in response to pressures caused by rising interest rates in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At that time, many insureds were borrowing cash values or cashing policies to invest the funds at higher rates elsewhere. Insurers felt pressured to offer high rates of return on the investment element in life insurance policies. This led some insurers to invest in high-yield bonds (often called unrated bonds, or, more commonly, junk bonds) and real estate. When the real estate and bond markets' performance deteriorated, it affected a number of life insurers' portfolios. Insurers might have weathered these adversities except for the policyholder runs. Withdrawals by insureds threatened to deplete the insurers' liquid assets, forcing them to liquidate mortgages and real estate in a depressed market. Regulators stepped in to stem the outflow of insurers' cash before the assets were depleted.7 Although many policyholders recovered from state guaranty funds, the insolvencies illustrated that the insolvency of life insurers is a real threat.

In Chapter 3, we discussed the insurer ratings that are published by A.M. Best and other financial rating services. These rating agencies are far from infallible, as evidenced by their failure to anticipate the approaching difficulties of the companies taken over by regulators. Still, given the complexities in insurance company accounting, we believe the insurer rating services are a valuable source of information. It makes sense to compare the ratings from several rating agencies. The higher the ratings and the more the rating services agree, the less is the likelihood the company will encounter financial problems.

Types of Policies Available Here, the matters of concern include the specific policy forms available (such as modified whole life, decreasing term, annual renewable term, family income policies, or special annuity forms) and include the availability of participating and nonparticipating contracts. Most major companies offer a wide range of policy forms including those discussed in the preceding chapters plus many others. However, a given company may not write a particular form of coverage in which the buyer is interested.

The availability of participating and nonparticipating contracts may be an important consideration. Mutual companies offer mainly participating policies, whereas some stock companies offer both kinds, and other stock insurers issue only nonparticipating forms. Under participating agreements, there is an opportunity cost to be considered in the excess payment that may be returned as a dividend. On the other hand, with nonparticipating policies, the insurer gets only one chance in pricing, and there is no provision for returning gains that may be realized from improved mortality experience or favorable investments. Although some people favor participating policies and others favor the nonparticipating kind, the preference of the buyer in this respect will be a determining factor in choice of company.

Cost Consideration Although most life insurance companies invest in approximately the same securities and start with similar mortality tables, there are significant differences in the premiums different companies charge for the same type of policy. This wide range of premiums makes the selection of a company and a policy a complicated process. Even though the premium for a whole-life policy with Company A is $10 per $1000 and the premium for a whole-life policy with Company B is $12 per $1000, it does not necessarily mean Company A is offering the better “deal” and that Company B is overcharging its customers. The differences in premiums do not mean differences in cost. In the case of cash value policies, the premium paid by the insured does not represent a true cost since a part of the payment goes toward the accumulation of the cash value. The cash value of Company B's policy may increase more rapidly than that of Company A. In addition, the settlement options or other internal policy provisions may be more liberal.8 Unfortunately, the provisions of Company A's policy may be more liberal or its cash value may increase more rapidly.

One of the most common fallacies about differences in premiums among life insurance companies is that these variations can always be traced to actuarial differences in the benefits of the contracts; in the field of life insurance, you get what you pay for. Although some discrepancies in premiums among companies may be traced to differing rates at which the saving elements of the contracts accumulate, to differences in dividends, and to differences in the liberality of policy provisions, the dissimilarities may be due to varying levels of expense and efficiency of operation. Since the company's operating expenses must be borne by the insureds, the levels of these expenses are important price determinants. Not only is internal efficiency important in price setting, but commissions and other acquisition costs may differ significantly among companies, resulting in wide differentials in the actual costs to the insured. New companies in particular, which are attempting to grow rapidly, often pay substantially higher commissions to their agents, and these commissions must be passed on to the consumer as higher premiums. For this reason, many consumerists suggest avoiding new life insurance companies. Others recommend dealing only with companies licensed to do business in New York State because New York imposes a statutory maximum on commission levels and requires companies operating in the state to observe this maximum in other states in which they operate as well. Most authorities recommend consumers should avoid credit life insurance because of its high commission expense and high premiums. It is a simple principle of mathematics that higher costs incurred by the company will mean higher costs to the consumer.

The popular misconception that “you get what you pay for in life insurance” is based on an unwarranted faith in the principle of competition. Some people maintain the marketplace will effectively keep a company from overcharging the public and that competition will result in an equality of value among companies. But is competition an adequate device for consumer protection in the field of life insurance? An increasing number of authorities maintain that the life insurance field has excessive prices, and to the extent that those excessive prices exist, competition is ineffective.9 In other words, when purchasing life insurance, one cannot always be certain of getting what one is paying for or that more attractive alternatives are not to be had. Competition is effective when the consumer is aware of the alternatives, and the complexity of price analysis has generally precluded this condition in the past. Although improved methods of cost comparison have become available, this remains a challenging area for consumers.

![]()

Comparing Differences in Cost

The simplest cost comparison in life insurance is between two nonparticipating term policies. Since neither policy provides dividends or cash value accumulations, a simple and straightforward comparison is possible. Once dividends or cash values are introduced, the process of comparison becomes increasingly complicated. Differences in premiums may be offset by differing rates at which the cash values accumulate or through dividends. With an increasing number of variables to be considered, and a complex pricing structure based on the variables, the insurance buyer can easily be misled.

Traditional System of Net-Cost Comparisons One widespread method of selling life insurance in the past used an illustrative projected net cost. Such proposals are misleading and the manner in which they are usually presented is fundamentally invalid. The basic technique is to sum the total premiums paid over some time period (usually 20 years), subtract projected dividends, subtract the cash value, and call the answer the net cost of the policy. The fallacy in this technique is it ignores the time value of money. An accurate appraisal of a proposed contract must include consideration of the opportunity costs involved.

To illustrate, let us consider two term contracts without cash values, one a nonparticipating contract with a $4 per $1000 premium and the other a participating contract at $6 per $1000. The net cost of the latter contract can be made to appear lower than that of the former: Company A charges $4 per $1000. The premium for a $50,000 policy will be $200 a year, and at the end of a 20-year period, the net cost will be $4000. Company B, on the other hand, charges $300 for the $50,000 policy and returns the overcharge at the end of the year as a dividend. It has the use of the $100 overcharge for a full year. Assuming that the company can earn 5 percent on the $100 overcharge, it can return a dividend of $105, making the net cost to the policyholder $195 for the year and the net cost over the 20-year period $3900. Thus, the overcharge on participating policies can permit a net-cost comparison and, ignoring the interest on the insured's overpayments, makes the cost appear lower. When dividends are left to accumulate, the opportunity cost becomes greater. Although our illustration used a nonparticipating policy and a participating policy for the purpose of simplification, the same distortion can result when both policies are participating but have differing levels of overcharge.10 The same approach may be used to distort comparisons of policies with different savings components.

Interest-Adjusted Method In response to the demand from many sources for a more accurate system of comparing life insurance costs, in 1969, the life insurance industry appointed a special committee, known as the Joint Special Committee on Life Insurance Costs. In its report, issued in mid-1970, this committee recommended an alternative cost comparison method known as the interest-adjusted method. As its name implies, the interest-adjusted method considers the time value of money by applying an interest adjustment to the yearly premiums and dividends.

In 1976, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) adopted a Life Insurance Solicitation Model Regulation and recommended it to the states for enactment. One part of this regulation requires that insurers provide buyers with a surrender cost index and a net payment cost index, which are two different versions of the interest-adjusted cost measure. The regulation also requires the insurer to provide the buyer with an equivalent annual dividend for the policy under consideration. Some insurers voluntarily comply with this regulation even in states where it has not been adopted.

Surrender Cost Index The manner in which the interest-adjusted method differs from the traditional cost method can best be explained through an example. Assume the policy under consideration is a $10,000 whole-life policy with a $240 annual premium. Projected dividends amount to $1300, and the cash value at the end of the 20th year is $3420. The traditional cost calculation uses simple arithmetic:

| Total premiums paid over 20-year period | $4800.00 |

| Less: Dividends received during the 20 years | 1300.00 |

| Net premiums over the 20-year period | 3500.00 |

| Subtract year 20 cash value | 3420.00 |

| Net insurance cost | 80.00 |

| Net cost per year ($80/20 years) | 4.00 |

| Net cost per $1000 | 0.40 |

This calculation shows that the insured's cost per $1000 of coverage over the 20-year period has been 40 cents per $1000. As we have seen, this is misleading in that it ignores the time value of money.

Calculating the interest-adjusted cost index for the same policy calls for a more involved computation:

| 20 years of premiums accumulated at 5 percent interest | $8333.00 |

| Less: 20 years of dividends accumulated at 5 percent | 2256.00 |

| Net premiums over the 20-year period | 6077.00 |

| Subtract year 20 cash surrender value | 3420.00 |

| Insurance cost | 2657.00 |

| Amount to which $1 deposited annually will accumulate in 20 years at 5 percent | 34.719 |

| For interest-adjusted surrender cost index, divide $2657 by $34.719 | 76.52 |

| Interest-adjusted surrender cost index per $1000 per year at the end of year 20 | 7.65 |

By accumulating the premiums paid by the insured and the dividends at interest, the interest-adjusted method considers the opportunity cost by reflecting the amount the premiums paid could generate at a conservative rate11 over the years used in the comparison. Although we have used a 20-year period, the computation is often made for 10 years. Subtracting the cash value from the accumulated premiums minus dividends indicates the insured's cost if the policy is terminated at the end of the 20 years, considering the time value of money. Dividing the cost by $34.719 indicates the number of dollars per year it would be necessary to invest and allow to accumulate at 5 percent to equal the $2657 cost of insurance.

Net Payment Cost Index The net payment cost index is a variation of the interest-adjusted method that attempts to overcome some of the criticisms leveled at the surrender cost index. The surrender cost index is different because the cash value is not deducted at the end of the 10 or 20 years used in the computation. In our example policy, the net payment cost index is computed by dividing the net premiums over the 20-year period ($6077) by the value of $1 invested annually at 5 percent ($34.719). The net payment cost index for the policy is $175.03, or $17.50 per $1000 per year.

Significance of the Indexes The surrender cost index and the net payment cost index are meaningless in themselves; they merely provide a basis for comparing one policy with another, and it is the difference in the index between two policies that is important. Small differences that may be indicated between two companies by either index are probably insignificant. The cost index is determined by the interest rate used, and a slightly different rate could result in a different cost advantage between two policies, particularly when the difference is small.

In addition, some companies may manipulate their cash value tables for the 10th and 20th years, the years for which the index is usually computed. This may make the policy appear more attractive at those points in time while it is far less attractive at all other times. New model life insurance disclosure legislation recommended to the states by the NAIC in December 1983 sought to address this problem. The 1993 NAIC model legislation requires a notation in the disclosure document when an unusual pattern of premiums or benefits makes the comparison of the cost index with other policies unreliable. It also requires notation when the dividend illustration for a particular policy is not made in accordance with the contribution principles.

Despite these shortcomings, the interest-adjusted indexes represent a vast improvement over the traditional net-cost approach to comparing policies. Given the length of time the insurer holds the funds, the opportunity cost is an important consideration. For the consumer who is willing to spend the time and effort to compare costs, the interest-adjusted indexes can be an useful source of information when used cautiously.

Other Cost-Comparison Techniques The interest-adjusted method represents one of two basic approaches designed to deal with the life insurance premium consisting of a payment for protection and a contribution to savings. Under the interest-adjusted method, an assumption is made concerning the rate of yield on the savings, and the cost of protection is calculated. A second approach is to make an assumption concerning the cost of the protection, and then calculate the yield on the savings element. Several models have been devised under which the return rate on a life insurance policy's investment element is calculated by assuming that the protection cost is the same as the cost of an amount of term insurance equal to the difference between the face amount of the policy and an increasing investment fund.12 The obvious advantage of this approach is that it provides a basis for comparisons between two cash value life insurance policies and between cash value life insurance and alternative investments. The Consumer Federation of America, for example, offers a service that will estimate the return rate on a life insurance policy by comparing the policy to the alternative of buying term insurance and investing difference in a hypothetical investment.13

Premium Payment Options Although life insurance premiums represent the annual cost for the protection, most insurers offer installment options under which the purchaser can pay the premium semiannually, quarterly, or monthly. The monthly option is frequently based on a preauthorized check system, in which payments are automatically deducted from the purchaser's bank account. Although these installment arrangements represent a convenience to the insured, the cost for the convenience can be substantial. An insurer with an annual premium of $1000 has a monthly payment option in which the monthly payment is $95. Using a standard annual percentage rate formula, the cost of the installment “convenience” represents a 30 percent annualized charge. Consumer advocates, such as Professor Joseph M. Belth,14 argue these arrangements types call for a more rigorous system of price disclosure in the sale of insurance.

![]()

The NAIC Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation

The NAIC's Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation originated as a response to deceptive sales practices based on misleading and incomplete policy illustrations. Although deceptive illustrations have probably existed from the earliest days of life insurance, they intensified in the 1980s when microcomputer software became available that permitted insurance agents to make policy projections using “illustrative” rates of return. A typical example was the so-called vanishing premium policy, a concept that was marketed in the 1980s. A vanishing premium policy was usually a participating whole-life policy with relatively high premiums and generous dividends. In theory, dividends would be allowed to accumulate until the accumulated dividends, plus anticipated future dividends, were sufficient to pay all future premiums under the policy at which point the premium would “vanish.” Vanishing premium policies enjoyed their greatest popularity during the 1980s when interest rates on such policies often reached 10 to 12 percent. The policy illustrations used in the sale of these policies projected interest rates of 10, 12, and 15 percent into the future, giving prospective buyers delusions of astronomical returns on their investments. In fact, in some instances, the agents represented the contracts as investments, retirement accounts, or even as pension plans. Once interest rates fell, premiums that “vanished” reappeared for many insurance buyers.15

In 1995, in response to alleged abusive practices in life insurance policy illustrations, the NAIC adopted a new Model Life Insurance Illustrations Regulation. By mid-2013, most states had adopted the model. Even where not adopted, most major life insurers have elected to abide by the model. The model applies only to sales of nonvariable life insurance. Variable life insurance is subject to Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) disclosure requirements, which specify items that must be included in the prospectus and standards for any illustrations.

The basic purposes of the model regulation is first, to ensure life insurance policy illustrations do not mislead consumers and, second, to make illustrations more understandable. To achieve these goals, the law establishes standards that apply to all group and individual life insurance policy illustrations except variable life, credit life, and insurance with death benefits not exceeding $10,000.

For each policy it sells, the insurer must inform the commissioner of insurance whether the policy will be sold with or without illustrations. If a policy is identified as one to be sold without illustrations, no illustration may be used in its sale. For policies identified as those to be marketed with illustrations, specific standards apply to the illustration used. All illustrations must be certified annually by an illustration actuary, appointed by the insurer. The actuary must be qualified according to the Actuarial Standards Board requirements regarding education, experience, and familiarity with the model law. The illustration actuary must be a member in good standing of the American Academy of Actuaries. The illustration actuary must certify that the assumptions in all illustrations used in marketing a policy comply with the model regulation and with the requirements of a new Actuarial Standard of Practice (ASOP), developed by the Actuarial Standards Board in cooperation with the NAIC's Life Insurance Committee.

Projected performance of a policy must be illustrated on three separate bases. First, performance is illustrated using the policy guarantees. Second, performance is illustrated under assumptions reflecting the disciplined current scale, an actuarial standard reflecting nonguaranteed elements that are reasonable, based on the actual recent historical experience of the insurer. The Actuarial Standards Board has developed the standards to be applied in the development of the disciplined current scale. It should reflect the most recently available experience on policies of the type illustrated but may not include any projected or assumed improvements in experience.16 Finally, a scale halfway between the guaranteed and disciplined current scale is illustrated.

Copies of illustrations provided to clients must be sent to the insurer along with the policy application. The copies must be signed by the applicant and by the agent. If an illustration is not used for a policy identified to the commissioner as one for which an illustration is used, the producer must inform the insurer, and the applicant must acknowledge the absence of a policy illustration. An illustration must then be sent to the applicant.

In addition to illustrations provided at the time of sale, the insured must be given an annual report, indicating the current death benefit, annual premium, current cash value, dividends, and any policy loans. If the annual report does not include an updated policy illustration, the insured must be informed that one is available upon request and encourage the policyholder to request it.

Other areas addressed by the model law prohibit certain activities of an insurer, its producers, or other authorized representatives. These include representing a policy as anything other than a life insurance policy, making misleading use of nonguaranteed elements, or using future policy values that are higher than possible under the disciplined current scale of the insurer. The model prohibits the use of the term vanish, vanishing premium, or similar terms that imply a policy will become paid up dependent on nonguaranteed elements.

![]()

NAIC Model Replacement Regulation

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners adopted a Life Insurance and Annuities Replacement Model Regulation in 1998 and subsequently amended it in 2000. By mid-2013, it had been adopted by 49 states. The model regulation established a new regulatory scheme for replacements and financed purchases of life insurance and annuities. (A financed purchase occurs when policy values from an existing policy, such as the cash values, are borrowed or surrendered to provide funds to purchase another policy.) Under the model regulation, if the sale involves a potential replacement, the agent must provide a notice regarding replacements that identifies some disadvantages of replacements and recommends the insured make a comparison between his or her current policy and the proposed policy. Insurance companies that are replacing an existing policy must provide the insured with a 30-day “free look” period, during which the policyholder can cancel that new policy and receive a full refund. Agents and insurers planning to replace a policy must provide written notification to the insurance company that issued the policy being replaced and, when requested, provide a copy of the policy illustration or policy summary for the proposed policy. The replacing company must provide credit for prior periods of coverage toward satisfying the suicide clause and, if the replacing insurer is the same as the original insurer, must provide credit toward meeting the incontestability period. The model does not apply to sales of credit life insurance or to group life or annuities in which there is no direct solicitation of individuals.

![]()

Investor-Owned Life Insurance

In the 1980s, a secondary market for life insurance policies developed, initially focused on individuals with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Investors purchased policies of terminally ill insureds, with the expectation of profiting from their investments when the insureds died. Insureds sold their policies because they needed the money and could obtain more than the policy's cash value by selling the policy in the secondary market. This sale of a policy on a terminally ill insured is known as viatical settlement.17

The secondary market for life insurance expanded beyond policies covering the terminally ill. The sale of a policy on an individual who is not terminally ill is known as a life settlement. Often, these are policies on the lives of elderly individuals and/or policies with very large face values.

The most recent development in this area is investor-owned life insurance (IOLI), also known as stranger-owned life insurance (STOLI) or investor-initiated life insurance. In this arrangement, an investor provides an individual with funds to purchase a life insurance policy, with the agreement that the policy will later be sold to the investor.18 The policy is never intended to benefit the insured or individuals with an insurable interest in the insured. Rather, the policy is purchased for the benefit of a third-party investor.

The life insurance industry has opposed the expansion of a secondary market in life insurance, particularly in the case of IOLI. In part, their opposition stems from concerns that the growth in the secondary market jeopardizes the special tax treatment of life insurance. As described in Chapter 12, life insurance is granted a special tax advantage, including a deferral on increases in the cash value. This tax advantage is justified because it encourages individuals to address the risk that the family's breadwinner may die. Investors in life settlements have no insurable interest in the insured. These are purely investments or, as one industry spokesperson has called them, “gambling on other people's lives.” Benefiting investors who obtain life insurance on strangers is arguably not what Congress had in mind when it created the tax advantage.19

In 1993, the NAIC adopted a model act on viatical settlements, placing viatical settlement companies under the jurisdication of the state insurance department. The model act requires viatical settlement companies to file a plan of operation with the state insurance department and requires disclosure to prospects of the alternatives to viatication and the tax consequences of the transaction. The original model covered sales of policies on terminally or chronically ill individuals, reflecting the state of the secondary market at that time. The model was subsequently amended to include life settlements. In 2007, the NAIC amended the model to address IOLI, prohibiting a life settlement within five years after the issuance of an insurance policy unless special circumstances occur. The special circumstances include terminal or chronic illness; the death of or divorce from the insured's spouse; or the insured's retirement from full-time employment.20

![]()

Industry Reform Initiatives

The alleged abuses in life insurance policy illustrations that prompted the NAIC to develop the model Life Insurance Illustrations and Life Insurance Replacement Model Regulations served as the motivation for efforts within the industry to address this problem. Two efforts are noteworthy.

Insurance Marketplace Standards Association (IMSA) One industry response was the creation of the Insurance Marketplace Standards Association (IMSA), which defined six Principles of Ethical Conduct for marketing life insurance and annuity products in the individual market and required member companies to undergo rigorous assessments of their compliance with the principles. The principles addressed such areas as fairness and service to consumers, fair competition, advertising and sales materials, consumer complaints and supervision of producers. The IMSA certification did not achieve widespread consumer recognition, however, and IMSA began to lose members. In 2010, IMSA created a new Life Insurance Forum for Ethics and Compliance (LIFEC) to assist industry compliance professionals and ceased operation.

Life Insurance Illustration Questionnaire Because of increasing awareness of the problem with life insurance illustrations, the American Society of CLU & ChFC developed a Life Insurance Illustration Questionnaire (IQ) for use in evaluating life insurance illustrations. The IQ consists of five sections (General, Mortality, Interest or Crediting Rates, Expenses, and Persistency). Each section contains a series of questions designed to elicit information about nonguaranteed performance assumptions used in life insurance illustrations. Properly used, the IQ can help reveal whether misleading assumptions have been made in the illustration. Use of the IQ by insurance companies or agents, however, is voluntary.

![]()

Shopping for Universal and Variable Life

Although universal life and variable universal life have widened the range of consumer choices, they have compounded the difficulty in shopping for life insurance. In fact, the increased flexibility of universal life and variable life will require consideration of so many variables that the decision process will become unmanageable. Before leaving the subject of buying life insurance, we should touch on the subject of purchasing universal and variable life.

Factors to Consider in Universal and Variable Life Costs The same three factors that are used in ratemaking in life insurance (i.e., interest, mortality, and loading) must be considered in evaluating a universal life policy. Unfortunately, focusing these elements may be difficult since they are uncertain at the time the policy is purchased and are often interrelated. The expense charges, for example, will determine the portion of each premium available for addition to the cash value. This, in turn, will determine the rate at which the cash value will increase.

Interest Although the minimum interest rate guaranteed in the policy is of some passing interest, it will not provide much helpful information in evaluating the product. More important is the interest credited to the policy. (Interest earned and interest credited to policies may differ.) In most cases, the interest rate credited to universal life policies is determined by the insurer from time to time, subject to the minimum specified rate. Prospective customers should ask the agents for recent fund performance reports.

Mortality The charge for the life insurance protection under most universal life policies is usually competitive with that of other universal life insurers and with traditional insurers. Nevertheless, the prospective buyer should determine the level of these charges as indicated by past and current practice of the insurer. While universal life policies indicate guaranteed mortality charges, these guaranteed rates are generally far more than the current charges being made and are of little use in evaluating the contract. Again, information on the insurers' current practice is of greater significance than the guaranteed rates.

Loading The differences among insurers with respect to expense charges and the complexities such charges introduce into the analysis are almost overwhelming. One company may charge a fixed fee of, say, $30 to $50 a month for the first year of the policy with only modest charges thereafter (a front-end load). Some companies make no charge when the policy is sold but charge a withdrawal fee when cash is withdrawn (a rear-end load). Another might charge 5 percent of each premium paid plus a charge for withdrawals. Sometimes, the additional charge for withdrawals remains fixed, and sometimes it decreases over time. Some companies charge a monthly or an annual contract maintenance fee, others charge an investment adviser's fee, and some retain a part of the investment income generated. With such a wide range of approaches to the expense charges for a universal life policy, comparing differences among policies is exceedingly difficult.

Universal and Variable Life Benchmarks The complexities of universal and variable life have led one expert to conclude that it is impractical to search for the lowest possible price and that the best one can hope to do is determine whether the charges for mortality and expense on a policy being considered are reasonably priced. For this purpose, Professor Joseph M. Belth has developed a model for comparing the cost of a universal life or variable life policy against a Benchmark. Basically, Belth's formula treats some funds as being invested in the policy and computes the cost of the insurance by assuming these invested funds earn some assumed rate of interest. Belth's formula for computing the cost per $1000 of protection is the following:

![]()

YPT is the yearly price per $1000 of protection, P is the annual premium, CVP is the cash value at the end of the preceding year, i is the assumed interest rate expressed as a decimal, CV is the cash value at the end of the year, D is the dividend (if any) for the year, and DB is the death benefit at the end of the year.

In the formula, the numerator computes the policy's total cost by comparing what the year-end fund would have been had it been invested at interest rate i with the actual funds available under the policy—the new cash value and the dividend. At the beginning of the year, the policyholder “invests” the cash value at the end of the previous year (CVP) and the premium (P). Had the insured invested the cash value and premium elsewhere at a given interest rate i, the funds would have accumulated to (CVP + P) × (1 + i). Because the insured invested them in the insurance policy, he or she has a new cash value (CV) and a dividend (D). The difference between what the insured would have had and what he or she does have represents the policy's cost. The total annual cost for the year is then divided by the amount of pure life insurance protection (logically defined as the total death benefit minus the cash value) to determine the cost per $1000.

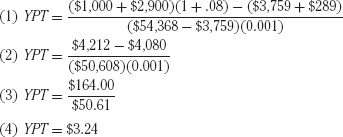

To illustrate the application of Belth's formula for computing the cost of insurance, assume the policy has an annual premium of $1000, the cash value at the end of the preceding year was $2900, and the cash value at the end of the current year is $3759, the annual dividend is $289, the death benefit is $54,368, and the interest rate is 8 percent. Inserting these values in the formula, we make the following computations:

The cost of protection per $1000 is $3.24. Once this cost has been determined, it can be compared with benchmark costs computed by Professor Belth using modest assumptions. According to Belth, if the yearly price per $1000 for the policy is the same or lower than the benchmark price, the combined mortality and loading is small. If the yearly price is higher than the benchmark but less than 200 percent of the benchmark, combined mortality and expense charges are medium. If the yearly price for the policy is more than 200 percent of the benchmark price, the combined mortality and loading is large. The benchmark prices developed by Belth are indicated in Table 17.2.

To perform the computations, the prospective buyer will need the following for the years to be measured: (1) the annual premium, (2) the cash value at the end of each year, (3) the annual dividend payable at the end of the year, and (4) the death benefit at the end of each year. An appropriate rate of interest must be assumed. Professor Belth recommends that the computation be continued up to and including age 74 for the individual.

TABLE 17.2 Universal Life—Variable Life Benchmarks

Table 17.2 includes front-end load multiples, which may be used to measure the size of the policy's front-end load. When the policy is front-end loaded, higher prices are charged in the first one or two years to cover sales and administrative expenses. If the policy is front-end loaded, the yearly price indicated by the computation will be substantially above the benchmark. However, if the frontend load for the policy is less than the multiple for the age as indicated in Table 17.2, the load is reasonable. When evaluating the front-end load size, the multiples for the first two years are combined. For example, if the front-end load is six times the benchmark in the first year and four times the benchmark in the second year, the policy multiple is 10.21

![]()

SOME ADDITIONAL TAX CONSIDERATIONS

![]()

Although the tax treatment of life insurance contracts was discussed in Chapter 12 and the special rules applicable to modified endowment contacts were discussed earlier in the chapter, two areas remain relating to the tax treatment of life insurance that should be mentioned. The first is the tax treatment when one life insurance policy is exchanged for another. The second is the special rules that may apply to the tax treatment of life insurance purchased to meet obligations under a divorce decree.

![]()

Section 1035 Exchanges (“Rollovers”)

Occasionally, an insured will decide to exchange an existing life insurance policy for a new contract, using the old policy's cash value as the initial premium for a new contract. The question arises concerning the tax treatment of any gain on the policy being terminated if the cash value exceeds premiums paid. As a general rule, the exchange of one life insurance policy for another life insurance policy will not result in recognition of a taxable gain for federal income tax purposes to the policyholder who exchanges the policy. The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) provides that the following are tax-free exchanges:22

- The exchange of a life insurance policy for another life insurance policy or for an endowment or annuity contract

- The exchange of an endowment contract for an annuity contract or for an endowment contract under which payments will begin no later than payments would have begun under the contract exchanged

- The exchange of an annuity contract for another annuity contract

If an exchange involves life policies, the policies must be on the life of the same insured; if an annuity is exchanged for another annuity, the contracts must be payable to the same person or persons. Otherwise, the exchange does not qualify as a tax-free exchange.

All other exchanges are taxable. This means that while the exchange of a life insurance policy for an endowment or annuity is not taxable, the reverse is false. Nonrecognition of gain or loss does not apply to endowments or annuities exchanged for life insurance contracts, and taxable gain or loss will be recognized if an endowment contract is exchanged for a life insurance policy or if an annuity is exchanged for a life insurance or endowment policy.23

The government's position on taxable exchanges is based on life insurance death proceeds being exempt from income tax, whereas living benefits under endowment policies and annuities are subject to tax. If exchanges of endowments or annuities for life insurance were allowed tax-free, it would permit the individual to accumulate funds under an instrument subject to one set of tax rules (endowments and annuities) and then exchange it for an instrument subject to different rules (life insurance). Consequently, the IRC views any exchange that increases the possibility of eliminating the tax by extending the period of life insurance protection or by providing life insurance protection where none existed, as a method of tax avoidance.

Even in the case of the tax-free rollovers, the recognition of gain is merely deferred. For tax purposes, the policyholder's basis in the new policy must be reduced by the amount of gain that is realized but not recognized, on the exchange. This means the gain will be recognized when the second policy is surrendered in a taxable transaction.

For policies subject to outstanding loans, care must be taken to ensure the loans do not result in a taxable event. If the loan on a policy is cancelled at surrender, the loan cancellation is treated as money received by the owner and can cause a part of the gain on the policy to be taxed. If the insurer issuing the new policy issues the policy with a loan equal to the outstanding loan on the old policy, the new loan cancels out the taxable event that would occur if the old loan were extinguished.

Aside from tax concerns, it is wise for insureds to be cautious when replacing life insurance policies for this area is fraught with abuse. Because life insurance policies can be complex, comparing two policies can be difficult. An unscrupulous or unknowledgeable insurance agent can mislead a policyholder into replacing an old policy with a policy less attractive than the old one. The issue of life insurance policy replacement has come under increasing scrutiny by the industry, consumers, and regulators. The term churning, originally used in the securities area to describe actions by brokers who engage in excessive trading of securities for customers with the primary purpose of generating commissions, has been applied to describe the actions of some life insurance agents. Observers note that the commission structure in life insurance, in which first-year commissions can be large, encourages agents to replace policies, thereby earning a new first-year commission. Some reformers have suggested that insurers should be permitted to pay a first-year commission only on the net increase in life insurance purchased. Others argue this would reduce the incentive of agents to periodically review the life insurance policies of insureds and recommend changes when they are appropriate.

![]()

Life Insurance and Divorce Agreements

Before leaving the subject of buying life insurance, an additional topic deserves mention: the uses of life insurance in meeting obligations under a divorce decree or other qualified domestic relations order.24 A divorce proceeding may require the purchase of new life insurance, it may require that existing life insurance be continued with the former spouse as beneficiary, or it may involve the transfer of ownership in existing life insurance policies to the former spouse. Each of these transactions can have tax ramifications for both spouses. In general, the tax treatment of premiums paid for life insurance in connection with a divorce settlement follows the rules applicable to alimony payments. If alimony payments are made on an informal basis, there is no tax consequence. The payer does not claim the payments as a deduction and the recipient does not treat them as taxable income. However, if certain conditions are met, the alimony payments are deductible by the payer and reported as income by the recipient. This will usually reduce the total tax bill since the payer is usually in a higher tax bracket than the recipient.

Life Insurance Premiums as Alimony Payments Under the rules applicable to divorce and separation agreements executed after 1984,25 alimony is deductible by the payer and taxable to the recipient as income if specified conditions are met. First, the payments must be required by an official agreement. In addition, the payments must be made by cash, check, or money order, and there is no liability to make payments after the recipient spouse's death. Finally, the payments cannot be scheduled to change after children are grown or finish school. (Amounts designated as child support do not qualify as alimony and are not deductible.) The IRC specifically provides that payments made to a third party on behalf of the spouse can count as alimony if they are made under the terms of the divorce or separation instrument.

Often, only the income-earning spouse is covered with life insurance, and unless required otherwise by the divorce decree, the insured spouse will change the beneficiary of his or her life insurance. Frequently, a court will require the beneficiary not be changed and may require the ownership of the life insurance be transferred to the dependent spouse as a part of the divorce settlement. When a life insurance policy transfer is incident to a divorce, no gain is recognized and the transferee is treated as having acquired the policy by gift. The transferor's basis is transferred to the spouse receiving the policy. Further, the transfer of an existing policy in connection with a marariage termination will not cause the proceeds of the insurance to be includable in the recipient's income under the transfer-for-value rule.26

The divorce decree may require the income-earning spouse to pay premiums on a policy designed to guarantee payments to the former spouse. In this case, tax treatment of the life insurance premiums (and proceeds) depends on the ownership of the policy.

When the alimony-entitled spouse is the policy owner, premiums paid by an alimony-obligated spouse for term or whole-life insurance on his or her life, with a former spouse as beneficiary pursuant to a divorce or separation instrument (executed after December 31, 1984), qualify as alimony payments. The premium payments that qualify as alimony are generally deductible by the spouse making the payments.27 This rule applies to policies assigned to the alimony-entitled spouse and to newly purchased policies of which the alimony-entitled spouse is the owner. Policy proceeds to the alimony-entitled spouse as policy beneficiary are treated as life insurance proceeds and are not taxable.

When the alimony-obligated (premium-paying) spouse retains ownership of the life insurance policy, the premiums are not deductible by him or her and are not taxable to the alimony-entitled spouse. At the time of the insured's death, installment payments of the policy's proceeds would be taxable as alimony to the divorced spouse. Also, payments from an insurance trust that is established to meet the obligations are fully taxable to the recipient. The same treatment applies when the alimony-entitled spouse's interest in the policy is contingent (e.g., if the policy will revert to the premium-paying spouse at the death of the alimony-entitled spouse).28

Funding Future Obligations by Annuity A spouse who is obligated to pay alimony can fund the payment of future alimony payments through the purchase of an annuity for the spouse to whom the payments are due. When an annuity is purchased to fund alimony payments under a divorce decree, payments under the annuity are fully taxable to the recipient beneficiary, and the beneficiary cannot recover the purchasing spouse's investment in the contract tax free. Further, the annuity purchaser cannot take an income tax deduction for the payments even though they are taxable to the spouse. Instead of transferring the annuity to the spouse, if the individual who is obligated to make the alimony payments purchases an annuity but retains ownership, he or she can receive the annuity payments, deduct the basis under the annuity rules and make payment to the spouse entitled to alimony. The payments would be deductible to the party making them and taxable to the recipient.

IMPORTANT CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

buy term and invest the difference

net-cost comparison

interest-adjusted method

surrender cost index

net payment cost index

vanishing premium policy

benchmark

NAIC Life Insurance Illustrations Model Regulation

QUESTIONS FOR REVIEW

1. List the three important considerations in selecting a life insurance company. How important is each relative to the other two?

2. Briefly outline the factors you would consider in deciding the answer to each of the three basic decisions involved in the process of buying life insurance.

3. Explain how the traditional net-cost system of life insurance cost comparison can be misleading to the consumer.

4. List and explain the most commonly offered objections to term insurance. How valid is each of these objections?

5. Briefly describe the tax advantage enjoyed by cash value life insurance as an investment. Does it have any disadvantages? Explain.

6. Why is it more difficult to evaluate a universal life product than a traditional whole-life product?

7. Identify the three factors used in life insurance ratemaking and explain how they are recognized in universal life insurance policies.

8. When selling universal life and other interest-sensitive life insurance policies, insurance agents frequently use a policy illustration that projects accumulated premiums and investment income. Identify the difficulties in making these projections. What should an individual look for when evaluating a policy illustration?

9. Briefly discuss the taxation of life insurance policy exchanges.

10. “In life insurance, differences in premiums do not mean differences in cost.” Explain this statement.

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

1. Income may be divided into two components: consumption and savings. Into which of these components do you think expenditures on insurance should be put?

2. What underlying assumptions are embodied in the advice, “Buy term and invest the difference”? What do you think of this advice?

3. When deciding on the type of insurance to buy, “the question is not one of term versus permanent insurance at all, but rather it is a choice between permanent insurance and alternative forms of investment.” In comparing permanent insurance with alternative forms of investment, what do you consider to be the most attractive features of insurance?

4. Some companies specialize in selling life insurance to college students. In many instances, the student is permitted to pay the first annual premium (and sometimes the second and third annual premiums) with a note. What do you think of this practice?

5. The guaranteed insurability option is a valuable form of protection, permitting an individual to insure his or her insurability up to some multiple of the face amount of the policy to which the option is attached. What do you think of the idea of marketing the guaranteed-insurability option by itself, without any form of current protection? Would it be marketable? Why or why not?

SUGGESTIONS FOR ADDITIONAL READING

Bajtelsmit, Vickie L. Personal Finance: Planning and Implementing Your Financial Goals. (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons, 2005).

Black, Kenneth Black, Jr., Harold D. Skipper, and Kenneth Black III, Life and Health Insurance, 14th ed., Lucretian, LLC, 2013.

Belth, Joseph M. The Retail Structure in American Life Insurance. Bloomington, Ind.: Bureau of Business Research, Graduate School of Business, Indiana University, 1966.

——— Life Insurance: A Consumer's Handbook, 2nd ed. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Federal Trade Commission. Life Insurance Cost Disclosure: A Staff Report of the Federal Trade Commission. Washington, D.C.: 1979.

Graves, Edward E. McGill's Life Insurance, 8th ed. Bryn Mawr, Pa.: The American College, 2011.

Murray, Michael L. “Analyzing the Investment Value of Cash Value Life Insurance.” Journal of Risk and Insurance, vol. 43, no. 1 (March 1976).

Reynolds, G. S. The Mortality Merchants. New York: David McKay, 1968.

Skipper, Harold D. and FSA Wayne Tonning. The Advisor's Guide to Life Insurance, American Bar Association, 2013.

WEB SITES TO EXPLORE

| American Council of Life Insurance | www.acli.com |

| Insurance Information Institute | www.iii.org/individuals/lifeinsurance |

| Life Insurance Foundation for Education | www.lifehappens.org |

| National Association of Insurance Commissioners | www.insureU.org |

| Society of Financial Service Professionals | www.financialpro.org |

![]()

1Wouldn't it be absurd if an insurance company approached the owner of a $1 million building with the proposal that the owner purchase $100,000 in coverage on the building and use the premium saved for an investment program? Yet, this is essentially what occurs in the life insurance field when individuals are persuaded to purchase high-premium, benefit-certain life insurance in an amount less than the required level of protection.

2We will defer our discussion of life insurance as an investment until the next chapter, which deals with the retirement risk.

3Concerning term insurance, the comment, “You have to die to collect”, is the most absurd criticism. The implication is that if you do not collect under an insurance policy, you have somehow lost in the transaction. One might as well say that your house has to burn down in the case of fire insurance or you have to run over someone to collect under your automobile liability insurance. The best approach to use on someone who makes such a comment is to refer the person to any insurance textbook that explains the operation of the insurance principle. Perhaps he or she will learn the insured receives something under an insurance policy without collecting.

4In addition to the insurer's capital and surplus, life insurance cash values are guaranteed by state insolvency funds, nearly all of which guarantee cash values up to $100,000.

5First Capital Life and Fidelity Bankers Life are subsidiaries of First Capital Holdings Corporation, whose largest shareholder is Shearson Lehman Brothers, Inc., a subsidiary of American Express Company.

6The problem of disintermediation for life insurers arises from higher returns on alternative investments. It was intensified by the failure of a few large life insurers.

7Although the seizure of Executive Life was the formal trigger for widespread concern about life insurer insolvencies, earlier indications existed that a number of life insurers faced financial problems. In 1990, of the 1926 life and health insurers in the NAIC's database, 482 had four or more IRIS ratios outside the usual ranges. See Joseph M. Belth, “A Watch List of Insurance Companies Based on the NAIC's 1990 IRIS Ratios” The Insurance Forum, vol. 17, no. 9 (September 1990). See also Joseph M. Belth, “Life Insurance Companies' Junk Bonds, Troubled Mortgages, Real Estate and Investment in Affiliates,” The Insurance Forum, vol. 17, no. 8 (September 1990).

8The first point to recognize in comparing cost among companies is that the policy provisions of the contracts are probably not identical. Disregarding cash values and dividends for the moment, there are other differences of great importance, and a price comparison of two contracts is valid only if the two contracts are identical in other respects.

9For example, see Joseph M. Belth, The Retail Price Structure in American Life Insurance (Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1966), and Life Insurance: A Consumer's Handbook (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973).

10Comparisons between participating and nonparticipating policies involve additional difficulties. Some allowance must be made for dividends under the participating policies, and since dividends usually increase under a policy as time goes by, they must be considered over the long run. At the same time, it should be recognized that future dividends cannot be guaranteed and are mere estimates based on past experience or future projections.

11The Joint Special Committee on Life Insurance Costs recommended 4 percent as the interest rate to be used because it felt this was reasonably close to the after-tax rate that could be earned over a period of years on personal investments with the same security and stability of life insurance. The 5 percent rate used in our illustration has replaced the 4 percent rate.

12For example, see Michael L. Murray, “Analyzing the Investment Value of Cash Value Life Insurance,” Journal of Risk and Insurance, vol. 43, no. 1 (March 1976), pp. 121–128.

13The CFA methodology imputes a cost for death protection using term life insurance rates in the market, then derives the estimated return on the cash value. See www.evaluatelifeinsurance.org

14See Joseph M. Belth, “The Arguments Against Rigorous Disclosure,” The Insurance Forum, vol. 22, no. 2 (February 1995). The majority of insurers will accept monthly premiums only if they are through an automatic fund transfer from the policy owner's account. Monthly premiums are normally 8.81 percent or 8.9 percent of the annual premium. This represents about 11.5 percent and 13.6 percent respectively.

15The disappointing return on vanishing premium policies generated thousands of lawsuits against the insurers that sold them, including class-action suits against Prudential, Metropolitan Life, New York Life, Crown Life, The Equitable, and other giants in the industry. The class-action suits purported to represent all the policyholders in the country or all the people in a particular state.

16To improve their illustrations, some insurers have included assumptions about improving mortality and lapse rates.

17The insurable interest in life insurance must exist at the time the policy is taken out. Thus, the investor purchasing the policy need not have an insurable interest in the insured. Investors purchased the policies with the expectation the AIDS patients would die within some short time period. With the development of antiviral drug treatments, the life expectancy of AIDS patients has increased considerably, and many investors lost money as they were forced to continue to pay premiums for longer than expected. Viatical settlements and their tax treatment are discussed further in Chapter 22.

18Typically, the agreement calls for the policy to be sold sometime after two years from policy issuance (i.e., after the incontestability period).

19Concerns that Congress could eliminate the tax advantages are not theoretical. In November 2005, the President's Advisory Panel on Federal Tax Reforms released its report. Among other changes, the panel recommended elimination of the tax-deferred cash value buildup of life insurance and annuity cash values. The advisory panel's report may be found at http://www.taxreformpanel.gov/

20There is an exception from the five-year requirement: If the viatical settlement occurs more than two years after the date of the policy's issuance, and until that time there has been no agreement to enter into a viatical settlement, then there have been no loans to fund premiums, and neither the insured nor the policy has been evaluated for settlement.

21See Joseph M. Belth, “Universal Life and Variable Life—How to Evaluate the New Wave of Products,” Insurance Forum, vol. 11, no. 6 (June 1984), pp. 21–24.

22IRC Section 1035(a); see also Revenue Ruling 68-23S, 1968-I CB 360 and Revenue Ruling 72-358, 1972-2 CB 473.

23Regulation Section 1.1035-1(c); Revenue Ruling 54-264, 1954-2 CB 57; W. Stanley Barrett v. Commissioner, 348 F.2d 916 (1st Cir. 1965) aff'd 42 TC 993.

24A qualified domestic relations order is a judgment or order that relates to the provision of child support, alimony, or property rights to a spouse, a former spouse, or a child that is made under a state's community property or other domestic relations law.

25Tax laws were changed in 1984, creating different tax treatment for payments under a qualified domestic relations order before 1985 and after 1984. Transfers prior to 1985 are subject to rules that differ from those discussed earlier.

26IRC Section 1041.

27IRC Section 215, Temp Reg. § 1.71–1T, A-6.

28IRC Sections 71 and 682.