CHAPTER 8

Kids 10–12: Growing Up

Zachary, Age 10

Reality has always been too small for the human imagination. We’re always trying to transcend.

—Brenda Laurel

Kids 10–12 are challenging for parents and designers alike when it comes to technology. These guys are not little kids anymore, and they don’t want to be treated that way. They tend to spend more time with apps like Snapchat and Instagram than they do on media geared toward kids. They use popular apps and games, but are starting to use technology more as a tool for information and communication than for entertainment. It’s becoming harder for parents to keep track of what their kids are doing digitally, since most of what kids do is on a smartphone or a mobile device. Parental controls, while effective, can undermine the trust that a parent has placed in a child, and this further complicates what’s already becoming a complicated relationship. Welcome to adolescence.

Who Are They?

As kids get older, it’s harder to pin down exactly who they are and what they need. Similar to designing for adults, doing research on the specific activities you’re designing for kids becomes more important to understand their expectations. Table 8.1 features some general guidelines to start with.

Take The Guesswork Out

Kids 10–12 are becoming masters of abstract thought. They’re able to interpret complex scenarios and imagine all the possible outcomes of their actions and decisions. This new ability to see things from other perspectives means that they sometimes agonize over what to do. Designing for these guys can be challenging, because while you want to build in flexibility for choice, you also don’t want to incapacitate your users so they’re unable to make a decision.

So, how do you get around this? How do you create designs that are engaging and complex without creating discomfort and indecision? The answer is simple: keep it simple. Let’s look at some examples.

TABLE 8.1 CONSIDERATIONS FOR 10–12-YEAR-OLDS

10–12-year-olds… |

This means that… |

You’ll want to… |

Can imagine the outcome of particular actions and decisions. |

They think and deliberate before acting. |

Take the guesswork out. Provide opportunity for complex decision making, but use simple design techniques. |

Can think creatively. |

They like to build their own scenarios and determine what the outcomes should be. |

Think about the “story” your interface is telling. Is it sequential? Are there multiple pathways? |

Have started using mobile devices much more than their computers. |

They experience most digital interfaces on a smaller, more intimate level. |

Even if you’re creating a website, design for mobile screens first. |

Are starting to become very aware of the things that make them “different.” |

They’re starting to feel like misfits, as if no one understands who they are and what they’re about. |

Celebrate individuality. Focus less on black-and-white answers and more on situation and context. |

See themselves less as “generalists” and more as “specialists.” |

As part of their self-identification process, they have honed in on the things that they like, the things that they’re good at, and the interests that make them who they are. |

Steer away from basic and general content and focus on particular areas of interest, such as art, music, science, animals, and so on. |

Kingdom Rush is perfect for the 10–12s (see Figure 8.1). It involves strategy, design, fantasy, bad guys, a little bit of blood, and lots of adventure. Kids have to protect their kingdoms from goblins and orcs by strategically building towers and enhancements on the road to the castle. The design is just detailed enough to be interesting, but the interface itself is simple, allowing users to focus more on the game’s objectives and less on figuring out how to do stuff. Since this game relies on strategic thinking, keeping the experience basic enables kids to consider their decisions and options instead of focusing on an overly designed, complex interface.

Kingdom Rush’s subtle design lets kids focus on strategy.

Based on their budget and on the type of enemy approaching the kingdom, kids have to choose what type of tower to build and where. Each tower has certain properties better suited to specific types of protection. As the enemy approaches, players can see how well what they’ve chosen to build will perform (see Figure 8.2).

Kingdom Rush uses representational, cartoon-like graphics to teach some interesting stuff like financial management, physics, and strategy. It taps right into the complex problem-solving skills these kids have developed and lets them imagine, interpret, and understand the consequences of their decisions in an interface that requires little-to-no interpretation.

Let’s contrast that with Machinarium (see Figure 8.3). Machinarium may be one of the most beautiful games ever. It’s got everything—gorgeous graphics, compelling storyline, intriguing characters—but it’s tough for 10–12s since the decision points are nuanced and unclear.

Kids use their deductive reasoning to build towers to save the kingdom from enemies.

Machinarium’s detailed interface makes decisions difficult for 10–12s.

The goal of the game is to help an exiled robot solve puzzles and collect items so he can get back to his city and rescue his girlfriend. Users explore and uncover wonderful environments to find the clues and save the day.

For concrete thinkers, like the 6–8s, this game is perfect. They take every decision at face value and plug along, enjoying the journey. For the 10–12s, who ponder the ramifications of every decision, this game can be agonizing. There are so many things to do and so many decisions to interpret that it can quickly become overwhelming. It’s interesting, because the designers of this game are clearly targeting a slightly older audience—there are veiled references to mature themes like smoking and drug use, and some of the puzzles require abstract thought—but younger kids seem to gravitate toward it. My friend’s 5-year-old son loves the game and can play it for hours, but another friend’s 11-year-old tried it for a few minutes and gave up.

This discrepancy occurs because games based on pure exploration are a little intimidating for the ‘tweens. In fact, they reflect on every decision point, and it can paralyze them. The interface is so finely wrought that kids 10–12 become too focused on what to do next instead of simply allowing the narrative to carry them through.

Don’t get me wrong, Machinarium’s an amazing game for kids and adults. It’s just a bit too open and exploratory for people who have just formed the ability to visualize multiple scenarios and implications of their actions. If you’re targeting ‘tweens, you’ll want to sacrifice some of the exploration and focus more on promoting creativity through decision making.

Let Kids Tell Their Story

One thing Machinarium does really well is to unfold its narrative and storyline. Kids can experience the adventure in a way that has meaning to them. Machinarium’s interface can cause discord as kids try to make the right choices, but if your design focuses primarily on the story (and uses the visuals to support this story), you’ll make 10–12s very happy. In addition to the ability to imagine different outcomes associated with their actions, ‘tweens can also think creatively. They like to craft their own scenarios and figure out different ways to negotiate an experience. While the younger users are primarily interested in the journey, the 10–12s are starting to become focused on the outcome and the destination. Your job as designers is to make this destination as interesting and desirable as possible, allowing ‘tweens to use their creativity to find their way through.

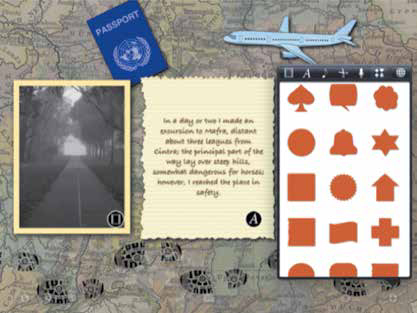

Some great work is being done in this area. For example, I really like Skrappy, an app that lets kids curate their own media in a meaningful way by telling their own stories (see Figure 8.4.)

Skrappy lets kids organize their photos, videos, and music around their life stories.

Children can choose from a variety of templates and import their videos, audio, and photos into a multimedia scrapbook. The design of the interface supports this goal without overwhelming users, letting them focus on the task at hand, as well as their own creative sensibilities. The great thing about Skrappy is that it offers suggestions, but doesn’t try to force users into particular directions based on the nature of their media (see Figure 8.5). It offers multiple pathways through the established narrative and invites users to experiment with these.

Kids can create their own pathways through Skrappy’s interface.

Skrappy handles multiple decision points, creative exploration, and personal narrative very well. The options are somewhat limited as of this writing, but as the designers continue to evolve the app, I think you’ll see some additional selections, allowing for even more self-expression.

Contrast that with Photo Grid – Collage Maker, which limits users’ engagement with the app and forces them to go down set linear pathways with little opportunity for kids to express themselves (see Figure 8.6). For kids who are obsessed with Instagram and other self-expression and sharing tools, this app seems like a no-brainer—take your photos and make them into cool collages to send to friends and family. However, the small number of canned templates, limited ability to customize the collages, contrived and juvenile assets available to add to the collages, as well as the ads that appear at the top of the screen make this app feel very confining and linear. This app is great for adults who want to dash off a quick collection of baby pictures to the in-laws, but feels oppressively constrained for our ‘tweens.

Interestingly, I had a blast with this app. I appreciated how quickly and easily I could create collages, I enjoyed the campy visuals I could add, and I liked how polished my finished product looked. But, as an adult, I value things like speed and immediate gratification while our 10–12-year-olds prefer to focus on ways to express and differentiate themselves. It’s another example of how you cannot assume that your users want what you want and like what you like, especially if those users are kids.

Photo Grid – Collage Maker is a bit too limiting for 10–12s, but perfect for adults.

PARENTS ARE USERS, TOO

When kids enter their ’tween years, the role of parents starts becoming even more complicated. Since kids of this age are starting to break away from parental control—many start choosing to do the exact opposite of what their parents ask them to do—it’s important to involve the parents and their concerns in what you architect, but in a way that doesn’t interfere with the child’s experience. For example, on some of the sites and apps you looked at earlier in the book, you’ve seen content geared toward parents, asking for their permission or just informing them about the experience and how it works.

With this age group, you’ll still want to include parents, but do it from the kids’ perspective. For example, instead of creating a section called “Parents,” or “For Parents,” you can create content directed toward kids, called “For Your Parents,” or “Give This to Your Parents,” so that the ’tween is in control of managing the relationship between parents and the experience. You don’t want to do anything to erode the trust between your app and your audience, so allowing kids to mediate the communication or even just informing them of what you’re doing goes a long way. (For example, “We’re going to send an email to your parents to get their permission for you to use our app. Tell them it’s coming and that it’s awesome.”) It will also empower more cautious parents to have the hard conversations about online privacy, predators, and purchasing.

Mobile First

Kids 10–12 use their cell phones much more frequently than they use their computers. In 2011, The Pew Internet & American Life Project1 estimated that 78% of all teens and ‘tweens have cell phones, and 23% have smartphones. That number is increasing annually, and the fastest-growing segment is the 10–12s. So what does that mean? Well, when thinking about the experiences you’re designing, make sure that you focus first on how it will work on a mobile device. Think about the context in which your young users will be accessing it. Are they on the school bus? In the cafeteria at lunch? Hanging out on the couch post-homework?

The mobile-first rule doesn’t just apply to apps. If you’re designing a site for 10–12s, you’ll want to think about how it appears on smaller screens first. Focusing on mobile will make it easier for you to identify the most important aspects of the experience, since screen real estate is more limited; it will help you cut out extraneous functionality you might have added had you been designing for a larger screen.

Let’s take a look at giantHello, a basic social networking site for ‘tweens (see Figure 8.7). The designers of this site didn’t create their mobile experience first. This fact is obvious, because in order to make the links and buttons on giantHello remotely touchable on a smartphone, users have to enlarge the page so much that most of it is cut off.

The giantHello site is cut off on a smartphone browser

When kids are on their computers, they’ll probably enjoy using this site, but since so much of their Web browsing and site usage is done on a mobile device, this site will quickly become cumbersome.

Not a lot of children’s sites are “mobile first.” As we see a move toward more and more sites using a responsive design framework, this will probably change, but in the current ecosystem, most sites geared toward 10–12s don’t function well on mobile.

There will be certain tasks your experience requires that will most likely have to be completed on a computer or at least a tablet. Things like registration, parental consent, or anything requiring the input of large amounts of data will be better served on a device with an actual keyboard. My recommendation is to figure out the main stuff first—the pathways through the actual experience, the interactions, the tasks—and worry about the supplemental stuff last. That way, you can be sure the important aspects are mobile-friendly.

Celebrate Individuality

This need to celebrate individuality might be the most important thing to consider when designing for kids between 10 and 12. As any parent of a pre-teen will tell you, and as you might vividly recall from your ‘tween years, kids in this age group are starting to come to terms with their personal differences. A perfectly “normal,” well-adjusted kid may start acting out in subtle ways starting at around age 10. Even kids who don’t exhibit any outward signs of rebellion are starting to feel more self-conscious, more noticeable, and more different than they used to. And the only way to address this in a digital space is to celebrate these differences.

When kids start feeling like misfits (and they all do, at some time or other), what you’ll want to do is let them discover activities that have meaning for them. We already discussed the importance of allowing kids to create their own personal narratives within digital environments, but it’s also important to start steering away from “right and wrong” or “black and white” and hone in instead on the gray areas in between.

This is also the age when some kids start becoming anxious about standardized tests, simply because they can see multiple outcomes of a given scenario and struggle with finding the specific right answer. The best experiences address this by self-discovery and by letting kids encounter and experience information in a way that resonates with their individual styles without, of course, making them anxious about whether the decisions they make within the experience are right or wrong.

I love Star Walk for kids (and adults) of all ages, but it’s especially great for the 10–12s. Basically, this app lets kids hold up their iPad to the sky and see the stars and planets directly above, almost like a window into space (see Figure 8.8). The imagery and music are mysterious, almost mystical, and let users form a very personal and very real relationship with astronomy. This intimacy and this celebration of the nuances among planets and constellations resonates with kids and lets them feel as though their individuality is beautiful as well.

Star Walk lets kids navigate the stars in an intimate, meaningful way.

Another wonderful example of designing for individuality is The Elements, an app created to teach users about the Periodic Table (see Figure 8.9). Like Star Walk, it gives kids a very personal, very different, very connected view into all the elements in the periodic table and celebrates the unique qualities and properties of each element. Even the most basic element is breathtakingly beautiful, and coupled with tons of detailed information, makes something as mundane as Tungsten absolutely amazing.

The Elements invites kids to explore and discover the Periodic Table.

Kids can choose to view the elements as quick overviews, with lovely photos and basic information, or they can delve deeper into longer explanations of the history and nature of each element (see Figure 8.10).

The photos, descriptions, and narratives for each element are so individualized and so finely crafted, it’s obvious the creators have a great fondness for them. This approach helps kids form a personal attachment to these elements and almost associate a personality to them, which is a great way to instill the love of science and learning.

TIP DANGEROUS APPS

There’s been a surge of interest among pre-teens in anonymous chat apps—like KiK Messenger, Yik Yak, Whisper, and Omegle—that let users message and share photos with strangers who live nearby. For these kids, who struggle with identity and crave attention, apps like these can create dangerous situations, frightening for parents and kids alike. If you have any type of chat mechanism available in your design, you’ll want to make sure that you’ve got levels of content moderation and abuse reporting in place.

In The Elements, kids can view detailed descriptions of the elements they want to explore further.

Specialize

While Star Walk and The Elements do a great job of allowing users to celebrate their individuality and build relationships with the world around them, their appeal extends to those kids who are truly interested in these subjects. Since children ages 10–12 are starting to figure out what makes them special, and since what they like and what they do are part of what makes them special, it’s important to create sites and apps for these kids that are highly focused and individualized in terms of content. For example, my cousin Kara, who is now an amazing, creative, brilliant adult, self-identified as a slam poet when she was about 12. She found something she was interested in and good at and focused her energies on developing her talent in that area, since that was how she saw herself. Kids prefer apps that allow them to do the things that make them feel special about themselves.

Along with the desire to use apps that support their individuality comes the desire to avoid apps that don’t support it. For example, if an 11-year-old-boy prefers writing to geometry, it’s going to be very hard to get him to download your geometry game. It’s also going to be very hard to get him to download any app that’s not focused on his areas of interest, regardless of how interesting those apps may be.

When setting up your absorption sessions with kids of this age group, make sure that you’ve identified a clear and narrow area of focus, and recruit kids with strong interest in that area. Otherwise, you will get fragmented data that will not allow you to architect an optimal experience for these kids.

Chapter Checklist

When designing for this group, think about how your design addresses the following issues.