CHAPTER 6

Kids 6–8: The Big Kids

Explain, Explain, and Explain Again

Saving, Storing, Sharing, and Collecting

Lilly, Age 6

Only a child sees things with perfect clarity, because it hasn’t

developed all those filters which prevent us from seeing things

that we don’t expect to see.

—Douglas Adams

I love designing for 6–8s best of all. Why? Because they’re introspective, complex, conniving, and open-minded, and still get incredibly excited by stuff they think is cool. They haven’t developed the healthy cynicism that comes at around age 10; they’re years away from ‘tween angst; they still like their stuffed animals; and they can read. They are the perfect combination of sophistication and innocence.

Who Are They?

You’ll have lots of chances to experiment when designing for these kids. Keep in mind, though, this is the age when kids start becoming influenced by what their peers do instead of what the adults in their lives do. That brings a whole new set of challenges, as shown in the characteristics highlighted in Table 6.1.

Outside Influences

When they start elementary school, children’s sphere of influence expands from that of their family and closest friends to include peers, teachers, coaches, and others. This experience helps them see objects, behaviors, and situations in different ways and from different perspectives. This additional awareness, coupled with an increased ability to pay closer attention to what’s going on around them, causes them to feel a little out of control. As a result, they look for situations they can master and orchestrate.

Let’s go through each facet in Table 6.1 and see what they mean when designing for kids in this age group.

Leveling Up

Kids from 6–8 have a much easier time focusing on tasks than they did when they were 4, just a few short years ago. This focus sometimes turns into a little bit of an obsession—kids will work on a particular task over and over again until they’ve mastered it. When designing for these kids, you can help support this focus by providing multiple levels of accomplishment, even if you’re not designing a game, per se.

TABLE 6.1 CONSIDERATIONS FOR 6–8-YEAR-OLDS

6–8-year-olds… |

This means that… |

You’ll want to… |

Are very focused. |

They like to master something completely before moving on. |

Incorporate concepts of progression, “leveling up,” and continued achievement. |

Prefer up-front knowledge to exploratory investigation. |

They don’t like guesswork. They’ll be less likely to explore and more likely to ask “What am I supposed to do here?” |

Be very clear at the beginning of the experience what the point is, what the kids will be doing, and why. |

Understand and appreciate the idea of permanence. |

They want to be able to return to an experience at any time and continue where they left off. |

Allow kids to save, store, and share the things they do. Create tie-ins between virtual experiences and physical ones. |

Feel a little out of control about the world around them. |

They’re very focused on following the rules, and craft elaborate guidelines for themselves and their behavior. |

Create a set of clear, easy-to-follow rules for them, but let them interpret and expand on these. |

Prefer quantity to quality. |

They like experiences that allow them to gather and collect, instead of simply excel. |

Incorporate basic gamification strategies (awards, badges, and so on) that they can earn and stockpile. |

Are starting to feel scared, suspicious, and distrustful of those they don’t know. |

They’re beginning to be hesitant about meeting new people and trying new things. |

Back away from social interactions and focus more on self-expression. |

For games, you should make the first few levels pretty easy to ace. Increase the difficulty, but give kids the feeling of accomplishment and mastery early on. As the levels go up, naturally, you’ll make them more difficult, but keep the delta between levels pretty consistent.

For educational sites and apps, it’s best to establish patterns of progression early on, so kids know the mechanics of what they need to do on each screen before they get there. This pattern lets them anticipate what they’ll come up against as they move through the interface. For example, when designing an interface to teach math, keep the general layout of the math problems the same across screens, but just increase the difficulty of the problems. You can change stuff like colors, icons, and animations on each screen, but make the basic structure consistent so that kids can feel a sense of comfort and familiarity. If users feel like they might not be able to accomplish something at first glance, they’ll be less likely to engage.

PBS Kids Go! offers a wide variety of games geared toward kids from 2–10, but 6–8s are their sweet spot. Because the developers are committed to building collaborative learning relationships with children, they make sure to feature games that can grow with the kids they’re trying to reach. Most of the games on the site, as well as their individual apps, start off with pretty general, easy-to-grasp activities and then get progressively more difficult as the kids are able to master them.

For example, the Fizzy’s Lunch Lab Freestyle Fizz game lets kids collect healthy foods like cheese, bread, and apples while avoiding French fries, hot dogs, and chocolate bars (see Figure 6.1). The game starts off relatively easy, letting users get used to the controls and figure out the best way to move around to collect the foods, but as kids level up, the game gets harder, with more items to collect and more to avoid.

Fizzy’s Lunch Lab lets kids level up in interesting ways.

Explain, Explain, and Explain Again

While younger children prefer to explore and learn as they go, 6–8s want all the information up front, to make sure they get it right the first time. Starting at age 6, opinions of others become super-important to kids, even if that “other” is a digital interface. They don’t want the game, or app, or device to think they’re dumb or unsophisticated. Having all the rules established before they begin makes these kids feel better prepared to excel.

It’s important to note, though, that if you find your interface requires a lot of explanation—say, more than a couple of short sentences—it’s probably too complicated and will likely turn kids away. These youngsters have just started to read, and if the directions make the experience sound too difficult, they won’t want to participate.

Of course, the best interfaces are those requiring little to no explanation, where kids can figure out what to do without reading instructions. So, similar to designing for adults, try to make the experience easy to figure out. Don’t use copy as a crutch for a confusing interface.

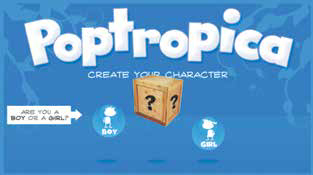

Poptropica, a virtual world where kids can create their own characters and engage in collaborative play with others, offers a very simple sign-up process that gets kids ready to start using the environment (see Figure 6.2). Although this process is broken up into several steps, it gives users a chance to fully understand what they need to do along the way and sets them up for success. While adults prefer to move through tasks quickly, 6–8s are more concerned with doing the task in the right way, so a greater number of clearly outlined steps works better for them.

Poptropica uses clear, visual explanations to help kids complete the registration process.

Contrast this with LEGO Creator’s Builder’s Island, an interesting and exploratory game, which lets kids build structures in a virtual world (see Figure 6.3). LEGO offers no instructions, just an overhead view of an island where kids are supposed to build. The interface isn’t very easy to figure out, and there are few instructions to guide children through the game. There isn’t even a place where kids can click to get more information.

This will pose a bit of a problem for 6–8-year-olds, who like to have all the facts before they begin using a site or an app. No matter how interesting a game looks, if they feel there is even a slight chance that they’ll mess up or get something wrong, these kids will be less likely to engage. So 8–10-year-olds, who consider themselves experts, will probably be undaunted by the lack of instructions here, but 6–8s will struggle. We’ll look at this in more detail in Chapter 7, “Kids 8–10: The ‘Cool’ Factor.”

LEGO Creator does not provide explanations or information on how to play, which will make 6–8-year-olds very uncomfortable.

Saving, Storing, Sharing, and Collecting

Children are able to grasp the concept of “permanence” at a pretty early age. If you move a toddler’s toy from in front of the couch to behind the couch, she’ll know that the object still exists, but it’s just hidden from view. What’s missing from the toddler perspective, however, is the idea of continuity—if a toy is behind the couch when you leave the room, it will still be behind the couch when you come back to the room, not in the toy box where it usually is. Kids figure out the continuity concept at around age 3, but they’re not able to apply it to intangible ideas or situations until they turn 6. For example, a 4-year-old will expect a movie or TV show to start from the beginning when he turns it on, while an older child will expect it to pick up where he left off. In fact, this older child will become distressed if the movie does not start up from the point at which he turned it off.

So, how can you reinforce this continuity in a digital environment? By allowing children to save and store their accomplishments within the experience and letting them easily resume play from the exact point where they left off. Webkinz, a virtual world where kids take care of digital pets, does this really well.

In Webkinz, kids collect and care for virtual pets. (These have an offline component too, which we’ll discuss shortly.) They build houses, which they can then furnish and decorate, for their pets, and can take their pets on adventures to play games and compete in contests. There are also a few “daily” activities, which kids can only play once a day, allowing them to collect rewards and “kinzcash,” which they can use to buy stuff for their pets.

The great thing about Webkinz is that it returns users to where they were when they last logged off. If they logged off from a room in their virtual house, they are returned to that same room. If they logged off from a game, they return to the game. Webkinz also reinforces the concept of continuity in how it treats the pets. If a pet was wearing a baseball hat when the user logged off, that pet will still be wearing the same hat when the user logs back on. This concept of permanence is both rewarding and comforting to kids 6–8. In a world where they feel increasingly out of control, it’s nice to have a consistent place to return to, where they can be assured that things will be just as they left them.

NOTE HISTORY OF WEBKINZ

Webkinz is one of the oldest and best virtual worlds for kids. Ganz, a Canadian toy company specializing in stuffed animals and collectible toys, launched the site in April 2005 to enormous fanfare. While its popularity has waned in recent years due to competitors in the space, it still sees about 3 million unique visitors each month. In 2009, Business Insider estimated Webkinz revenue to be about $750 million annually.

Webkinz’s daily activities also help with permanence and continuity. In the daily Gem Hunt game, kids dig in virtual caves for gems they can collect to complete their “Crown of Wonder” (see Figure 6.4). They can only go on a gem hunt once a day, which both increases the desirability of the activity and the consistency of play, but they can look at their collection of gems whenever they want. This concept, of a growing virtual collection, is very attractive to kids and results in a significant increase in daily site visits.

Another way that Webkinz furthers the ideas of permanence and continuity is by selling a complete line of stuffed animals to match the pets in the virtual world. In fact, kids must have an animal and an entry code in order to start using the site at all. When kids sign up online, using the entry code that comes with their stuffed animal, a virtual representation of their toy appears on screen, which they can then use to play games, dress up, and care for in the environment. Having a physical connection to a virtual entity is amazingly compelling to 6–8s. It’s a consistent reminder to log in to the site, but it also extends the concepts communicated in the virtual world. Kids can collect both the stuffed animals and the virtual pets and build their own communities.

TIP TAKE-AWAYS ADD INTEREST

The 6–8s love having physical reminders of what they do in a digital space. A great way to provide this connection between the virtual and the physical is to create printable certificates, badges, and awards for kids to download and collect.

Webkinz reinforces permanence and continuity in its daily gem hunt.

High Scores

The ability to save and share high scores or achievements in a digital environment is exciting to children, too. Not only does this let them chart their progress, but it also gives them tangible goals to work toward. For example, if kids set a personal goal to spell 100 words right in a spelling game, they can continue to work toward that goal in a cumulative fashion and see where they improve instead of starting from scratch each time.

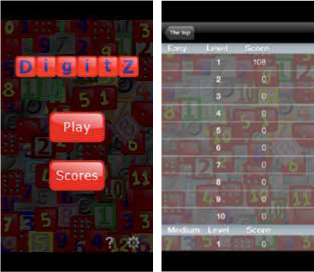

Let’s take a look at DigitZ, a tetris-like math game for iOS. The great thing about DigitZ is that it lets kids go back and see their score for every level of the game they’ve completed, from the easiest to the hardest (see Figure 6.5). In fact, the two main calls-to-action on the landing screen are to play the game and to view their high scores.

This ability to see scores right away allows children to chart their progress, lends permanence and flow to the game itself, and motivates them to continue to excel. Establishing these goals at the outset of the game and being transparent about what kids are working toward helps keep the momentum going and inspires continued play.

DigitZ lets kids see their scores easily.

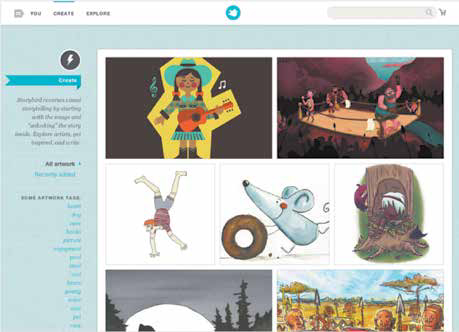

Sharing

The wonderful Storybird site is great for kids of all ages, but 6–8s will especially love it because of the way it lets them use their newfound storytelling and deductive reasoning skills. Storybird has mastered the art of letting kids share stories in a safe, yet meaningful way. As per the site, “Storybird reverses visual storytelling by starting with the images and ‘unlocking’ the story inside.” It lets kids make up their own stories by first choosing a series of illustrations from a huge repository of images and then crafting tales around these images (see Figure 6.6).

Storybird lets kids choose image collections and craft stories around the images.

In school, students “write” stories first and then illustrate them after they have the basic narrative down. Storybird lets children turn the process inside out, by using images to spark ideas and letting the kids develop the ideas from there.

Storybird has an ecommerce component, where parents can purchase printed versions of the stories their children create. I’m not normally a fan of kids’ sites that encourage the purchasing of products from within the experience, but the permanence and tangibility of the Storybird books create a robust all-around experience for the 6–8-year-olds. Kids can also write stories and post them on the site, for others to read and enjoy, free of charge.

After kids select the collection of images they want to use, they are guided through the “writing” process via a simple, clear, representational interface that lets them watch the book evolve as they create it, as shown in Figure 6.7. Younger children may need parents to help them enter the text, but early readers will be able to jump right in and start writing.

Storybird’s clean interface allows kids to focus on being creative without getting in the way of that creativity.

Playing by the Rules

I did an observational study with some second-graders a few years back, where I got to watch groups of friends play together. I took them into a separate room with no toys or books, and asked them to play while I got my “papers” together. Most of the groups decided to play rock band (which is evidently this latest generation’s answer to “house”). The most fascinating aspect of this free-play activity was that the groups spent most of the time coming up with roles and rules instead of actually engaging in the role-play. They first decided who everyone on the group was going to “be.” As is typical with second-graders, one kid stepped up as the leader and started assigning roles. When she told one little girl that she’d be the drummer, the little girl said, “I don’t want to be the drummer; I want to be a veterinarian.”

The game came to a screeching halt. After all, there aren’t too many veterinarians in rock bands these days.

Kids start really focusing in on rules at around age 7. They are beginning to see how big the world really is, and the concept of rules—to govern behavior, interactions, and communication—is extremely comforting to them. They develop elaborate rules for how they play, talk, and generally conduct themselves. And they hold others in their social sphere to these same rules.

This presents really interesting implications when designing virtual environments. We know kids like rules, but when the rules for a game become too limiting or too difficult to follow, they’ll find something else to do. The trick is to develop a clear set of rules that are easy to understand and follow, but flexible enough for kids to make their own. This is easier for games with specific objectives, and it’s more difficult for environments that rely on exploration and self-expression.

Let’s take a look at what the folks at Club Penguin are doing.

Club Penguin is a virtual world for kids and adults (see Figure 6.8). It lets kids create penguin avatars and move through a virtual arctic environment where they can play games, chat, and build their own igloos. The Club Penguin creators developed a robust yet flexible set of rules that help kids (and parents) feel comfortable moving through the interface.

Club Penguin’s rules are both easy to follow and flexible.

The great thing about Club Penguin’s rules is that, although they cover some serious business, they’re written to support free play and focus on safety and community. This application gives kids and parents a sense of comfort and control within the space, while at the same time encouraging them to have fun. The image of the penguins high-fiving each other reinforces the sense of community that the creators are trying to convey.

This concept of flexible rules may seem to be at odds with what we discussed earlier about providing clear, concrete explanations. The difference here is, rules provide global structure to an overall interface, while instructions provide specific information about individual components. The former needs to be elastic and allow for some interpretation, while the latter needs to be detailed enough to ensure success and accomplishment.

So what happened with our rock band? The young ringleader, who struggled with the idea of a veterinarian in the midst of her musicians, was able to bend her rules to create a compromise. “Well…you can be the VETERINARIAN drummer!” The aspiring veterinarian was happy, the leader was happy, and the other players were comforted at the possibility that one could be both a veterinarian and a drummer at the same time.

TIP MAKING THE RULES

Make sure that the rules you create for your site or app are clear and easy for children to follow with little to no interpretation. An example of a well-constructed rule might be: “When writing a story, try to use pictures and words that are positive and respectful.” A poorly constructed rule would say: “Don’t curse or use words that could be considered offensive, dirty, or insulting in your stories.”

We Need Some Stinkin’ Badges

It’s true that 6–8s love to gather and collect stuff. When my brother was about 7, he started collecting mini soaps from hotels. Whenever we went on a family vacation, he would take a couple of soaps from the bathroom, wrap them in tissues, and place them carefully in a special toiletry bag. These not only served as physical reminders of our trips, but also let him accumulate “proof” of all the places he’d been, almost like stamps in a passport. This type of collecting is equally important in a digital space, for both kids and adults.

Let’s think about the implications of this concept on behavior modification. If you’re consistently rewarded for positive behavior, for example, exercise, smoking cessation, losing weight, you’ll be more likely to continue this behavior. This is true for kids, too. When kids associate behavior with positive outcomes, it fosters the desired behavior. If you want kids to do certain things within your interface, give them cool stuff for doing it. This behavior-reward system is the basis of “gamification.”

Unfortunately, “gamification” has almost become a pejorative term for designers. It conjures up images of false accolades, meaningless rewards for common behaviors, and unimportant milestones to share via social networks. When it comes to designing for kids, however, the concept of gamification is very powerful. It’s digital proof of all the cool stuff they do online.

Fortunately, it’s easy to do this well. First, identify the key behaviors you want to reward within the experience you’re designing, and then identify a simple way for kids to accumulate stuff for doing them.

When I was working on Planet Orange, a virtual world designed to teach children financial literacy, we wanted to include something that would serve as an impetus for kids to complete all the activities on the site. We created a series of badges that users would earn after finishing the projects on each continent on the “planet” (see Figure 6.9). We also created printable certificates that kids could hang up to celebrate their accomplishments.

While our ideas were founded on the correct principles, we overcomplicated the rewards model. Since the site was about money, we created a complex currency structure, in addition to the badges, where kids could earn “money” to buy stuff for their personal space stations and astronaut avatars (see Figure 6.10). The problem was, we were rewarding the same behaviors with both badges and currency. So we essentially diluted the importance of both badges and money—called “o-bux”—resulting in the devaluation of the activities on the site. Lesson here: Too many rewards for similar behaviors makes the reward structure become meaningless. Collecting items is an effective way to learn, but only if you’re collecting stuff that reinforces the ideas you’re learning.

Bottom line: Using badges and awards to encourage site use is compelling for kids. Just make sure that the awards you give support the right behaviors in the right way.

Planet Orange awards badges for completing activities.

Planet Orange also provides currency rewards for completing the same activities.

Stranger Danger

By the time children reach the age of 4, they’ve been more than adequately warned about the perils of talking to strangers. In fact, many of them are quite frightened at the prospect of being around strangers, let alone talking to them. This fear continues to grow as kids get older and wiser about the ways of the world. However, a normal healthy fear about encountering strangers in the real world can turn into abject terror when dealing with the notion of strangers in digital space. This is because anyone can be a stranger, even someone who seems to be a regular kid just like them. There is no real way to know if the person you’re talking to online is 8 or 80, and that lack of control and knowledge can be truly terrifying to a child. This “stranger danger” fear presents implications when designing for this audience, because if the experience you’re designing has a large social component, kids will be less likely to engage.

As the power of technology continues to evolve, many companies want to inject a social element into their kids’ experiences, simply because the ability is there. It’s true that collaborative learning and exploration works really well with children, but only if this collaboration can be done anonymously. To most kids, “social” means saying hello to folks in the hallway, not interacting with them online.

It’s possible to design for meaningful online engagement with a child audience, but you have to proceed with caution. For example, crafting a robust set of rules around interaction, as Club Penguin does, helps kids and parents feel more comfortable in a given space. You can also leverage “canned” messages for kids to send to each other, to foster communication without real free-form interaction.

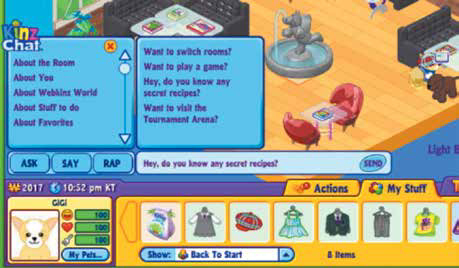

The people at Webkinz also do a nice job with “canned chat” (see Figure 6.11). Kids can pick from a set of preselected topics and choose pretyped messages, called KinzChat, to communicate with others in the virtual world.

Webkinz lets kids message each other, but only via canned chat.

However, children cannot type in free-form messages to each other at Webkinz, thereby eliminating the possibility of inappropriate or predatory interactions. This structure helps kids feel more comfortable in an interactive environment without worrying that a stranger will start up a conversation.

Other sites, including Club Penguin, let parents pick the level of interaction they want their kids to have with others. Part of this is due to COPPA regulations (see the interview with Linnette Attai at the end of this chapter), but part of it is based on a conscious design decision to help kids feel safe. Club Penguin offers levels of use, which range from no chat mechanism at all through full free-text messaging. The 6–8s tend to prefer the middle ground, which gives them the opportunity to communicate in a limited capacity with pre-existing messages.

Designing Canned Chat

When designing a canned chat experience, make sure that the topics are varied enough to appeal to children’s different interests, but not so broad as to be confusing. Additionally, make sure that the phrases you allow kids to use are easily understood. Use short words and sentences, and reflect the nature of the experience you’re designing.

An effective use of canned chat is to develop a series of questions that kids can ask each other and provide appropriate responses for kids to use to reply. For example, a question like “What’s your favorite animal?” is a great way for kids to open up conversations online in a non-threatening way, become comfortable with the idea of communicating, and share information about themselves. The answers you provide for them to use should range from safe to exciting, and should let the kids feel some element of self-expression. For example “cat,” “dog,” “monkey,” “elephant,” and “wooly mammoth” represent a good range of options. Limit the options within each category to five and under, as kids have difficulty choosing from lots of different selections.

Most likely, you won’t be able to craft a broad enough set of generic messages to use all the time. So what you can do is offer different message types based on context. For example, if your experience allows kids to compete in a game, push messages like “nice shot!” “way to go!” and “let’s play again.” If you’re encouraging kids to communicate in a creative or building environment, messages like “great idea!” “nice picture!” and “cool design!” let kids comment on each other’s work. For 6–8s, you’ll want to avoid negative messaging, and you may even want to stay away from neutral messaging (for example, phrases like “not bad”) since kids aren’t great at interpreting meaning. When they get older, and become a little more experienced at context and subtext, you can weave in more constructive messages.

The Anonymity Factor

There are problems other than the children’s comfort level in offering open chat communication. The concept of anonymity is extremely seductive to people of all ages. Think about it—if you could say anything you wanted to anyone you wanted and no one would know it was you, what would you say? It’s hard for adults to control what they say under the guise of anonymity, and it’s even more difficult for kids.

Especially kids who are learning new naughty words almost daily. In addition, the idea of “Internet predators” has taken on a life of its own. While it’s highly unlikely that a real predator will approach a child in your digital environment, there are plenty of creepy people out there who will say creepy things. You want to limit the opportunity for the creepy to come out in the experience you create.

When researching for an article a year or so ago, I signed up for an account on the Barbie Girls site (which has since been shut down). I signed up for the most “permissive” account, giving me full access to view and create free-form messages. Almost immediately, another “girl” approached me, and began asking extremely suggestive questions, about what I was wearing and whom I was with. I played along for a little while, to see how far this person would go, until I decided to report her (him?) to the site moderators, who promptly blocked her. As an adult, I was able to quickly assess the situation and report the creepy person, but for an 8-year-old who really, really wants to be liked, it might not be so clear-cut.

Other good ways to foster communication in a safe and positive manner are to allow children to post stuff that they’ve created and allow other kids to comment on it, using canned chat, or “stickers,” or badges. The 6–8s love to express themselves and share their thoughts and ideas, so it’s a good idea to create an outlet for that, even for something as simple as showing their high scores.

PARENTS ARE USERS, TOO

When you’re designing an experience for kids, it’s always good to have a section for parents. Even if you don’t use any communication tools or collect any personal data, you’ll still want to let parents and adults know a little bit about your environment: what the goals are, what you hope kids will come away with, and so on. Parents will be more likely to let a child use or download a site or an app if they understand what it’s for and how it will be used. You also may want parents to play a role in helping their kids get the most from the experience. For example, usage tools and tips for adults can help encourage adoption and engagement.

Chapter Checklist

If you get the opportunity to design for a 6–8-year-old audience, I encourage you to take it. It will be a blast, and you’ll learn a lot from these savvy little customers. When designing for this crew, answer the following questions.

Interestingly, 6–8-year-olds have more in common in terms of attitude and behavior with 10–12s than they do with 8–10s. When we dive into how to design for 8–10-year-olds in the next chapter, you’ll see how they represent their own unique little pocket of awesome.