democratic and more coercive than he sees himself; however, this is

not a great cause for concern in this particular example. Andy is

genuinely supportive of his team – as demonstrated by the high

scores he receives under the ‘affiliative’, ‘democratic’ and ‘coaching’

headings. This indicates that he is a ‘nice guy’ who has made it to the

top. For such individuals, the power and status of a senior role are

not the main attraction; they value the personal qualities they have

retained, and so naturally tend to underestimate the effect that the

impact of being ‘the boss’ has on other individuals. When he

suggests that the team does something, he can believe he has been

affiliative in style, but because he is ‘the controller’, at least some of

his team interpret it as an order. Hence the higher score under the

‘coercive’ heading than he would give himself. This is a common

dynamic and, provided the gap between the real and perceived

attribute in this area is not too great, it is not a cause for concern.

Indeed, there is a more even spread of leadership styles in the

feedback from his team, than in his own perception; indicating that

he is a more balanced leader than he himself realizes.

The coercive style is still low (it probably would have been higher

earlier in his realm as controller – see Chapter 8). As indicated in the

discussion of the coercive style above, he would probably not want to

increase his score here. Andy works in the creative business, for the

market leader in popular music radio in the UK, the employer of choice

for every DJ in the country. He is not going to be working with people

who lack motivation. He is nurturing people with considerable creative

talent and in some cases massive egos. This requires intelligence,

sensitivity and a good range of emotionally intelligent skills.

Beliefs drive behaviour (and an example of how

workaholic beliefs can distort our perceptions)

Beliefs are very powerful things in our lives, and behaviour is

organized around beliefs. Often to help us change some of our

behaviours we need to examine our beliefs and values systems,

otherwise behaviour change is superficial.

It is our contention that everyone possesses beliefs and is guided by

them. It is also our contention that beliefs can change. You are not

born with them. We have all believed things when we were young

which we now look back on and consider rather stupid, and certainly

not helpful today. We are not just talking about Santa Claus or the

tooth fairy. We can feel embarrassed, for example, about a rather

extreme political stance that we adopted while at university.

But some of the most pervasive beliefs that matter to how we

manage do not lie within the realm of legend or philosophy or

politics, but relate to our views on work, families and careers, some

of which we discussed in Chapter 2. Imagine if, for example, you had

grown up to believe that all women who are married with children

should not work full time until their children leave home. How

would you feel then moving into a role where your new boss is a

woman with three children all under the age of 11? Or you might

believe that people only get somewhere in life by ‘working hard’ and

‘doing it all yourself’. In our experience, we have certainly met many

executives who are workaholics and who struggle to build strong

teams beneath them.

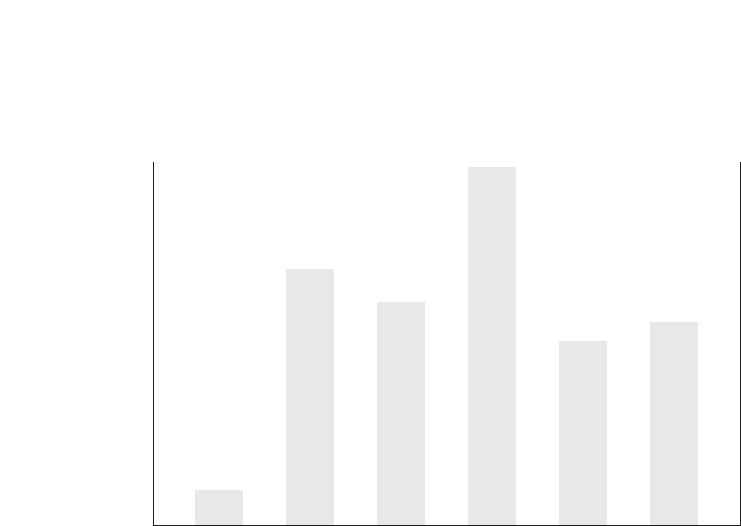

Poor self-awareness of a pace-setting boss

Bob (not his real name) had a very strong belief that in order to be a

successful manager you should be fair and very firm, but certainly

not friendly. In fact he believed that if people liked you, found you

empathetic, and you took an interest in them and their careers, you

were bound to be a ‘poor’ leader. He developed a management style

that was dominantly coercive and pace-setting. He had had feedback

over a two-year period that as a partner in a large legal firm more

junior professionals were not keen to work with him, despite the fact

that he usually sold the most interesting assignments.

His clients thought his work was exceptional, so the firm realized it

had to deal with the problem before he hit burnout. To deal with

high staff turnover in his team, Bob worked long hours and did a lot

of the technical work himself. Most of the time he was exhausted. His

management style and climate data showed a large gap in how he

momentum complete leadership chapter five

93

pages 92 /

perceived himself, and how his team perceives him (see the charts on

pages 95 to 100). He saw himself as authoritative and democratic;

they saw him as coercive and pace-setting.

Data on the climate and mood he created around him showed low

team co-operation, and reward, and poor clarity and standards. No

wonder poor Bob had to work so hard. Importantly, Bob had had

similar feedback for three years running now and had still not

changed. He did try from time to time, but kept slipping back to old

habits. Only when he worked through D-3 of the 3-D model (see

page 107) was he able to reframe his beliefs and begin to work on

changing his behaviour. Not only did the performance in his team

improve but contribution of his team to the profits margin of the firm

increased by 8 per cent.

The charts we have discussed of Andy Parfitt and of Bob give a vivid

and comprehensive picture of our level of self-awareness derived

from a relatively simple questionnaire process. Remember, this is an

established process, not just a theory, and it has been used to help

thousands of managers improve their performance. They show how

Andy had a strong level of self-awareness and that, initially, Bob did

not. The point to emphasize here, however, is that self-awareness is

an improvable ability, like any human skill. Bob had the integrity

and honesty to work hard on this aspect of himself; specifically

confronting his deeply embedded belief, which he had probably

carried since childhood, that empathy and friendliness were

incompatible with leadership. This belief had stymied his self-

awareness and his growth as a leader. It had caused him to consider

himself more authoritative than was experienced by his team, but he

did possess the courage to challenge this belief, leading to the

improved performance of his team, and ultimately to better business

results.

To deal with high staff turnover in his team, Bob

worked long hours and did a lot of the technical work

himself. Most of the time he was exhausted.

momentum complete leadership chapter five

95

pages 94 /

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

9.9

Coercive Authoritative Affiliative Democratic Pace-setting Coaching

70.2

61

97.6

50.3

56.8

Percentiles

66 = Dominant

50–65 = Backup

Management style inventory (Participant version)

Source:

Hay Group, 2002

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

60.6

Coercive Authoritative Affiliative Democratic Pace-setting Coaching

13.5

8.9

42.4

95.1

12.5

Percentiles

66 = Dominant

50–65 = Backup

Management style inventory (Employee version (N = 6))

Source:

Hay Group, 2002

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.