198 CHAPTER 9 GETTING TO NET PROFIT

As the name implies, a finance lease is a sneaky way of financing an asset. In essence, it

produces a liability (to pay for the asset) that is hidden off-balance-sheet. Many countries

have introduced the generally accepted accounting principle that requires finance leases

to be shown on the balance sheet as an asset and as a matching liability. The starting

value on both sides of the balance sheet is the net present value (see Chapter 11) of the

minimum lease payments. Depreciation is over the shorter of the term of the lease or the

assets’ expected useful life. The excess of annual lease payments over the depreciation

charge is charged to the profit and loss account as interest.

Operating leases are just charged to the profit and loss account as an expense (such as

‘computer leases’).

In Chapter 11, I explain some simple arithmetic with an off-putting name. This is the

internal rate of return (the discount rate in net present value). It is used in assessing whether

or not to acquire an asset. It is also helpful when deciding whether to lease or buy – you

use it to compare the relative costs of the two options. Leasing is often especially attrac-

tive to new businesses because it averts a big up-front cash outlay.

‘Expenditure rises to meet income.’

C. NORTHCOTE PARKINSON. OPENING SENTENCE FROM THE LAW AND THE PROFITS

Accounting for fixed assets

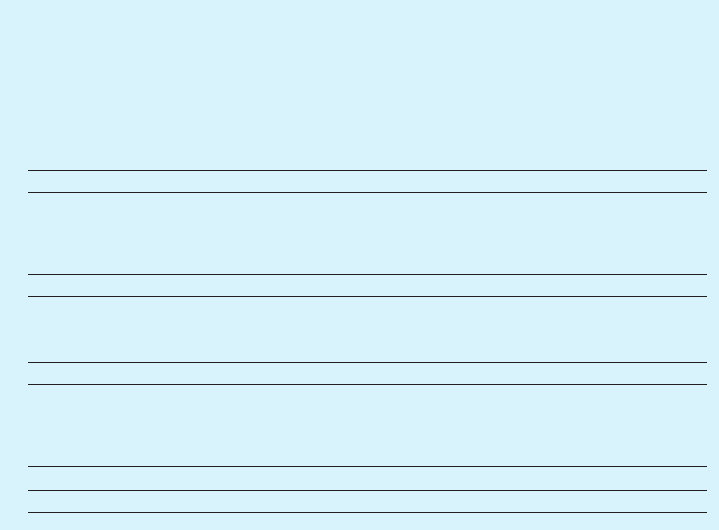

This is how you account for fixed assets in your monthly projections. Suppose that:

in October you will acquire a clumping machine for $120,000 (see Figure 9.1);

it has an expected life of five years (60 months);

you are using the straight-line depreciation method.

Outlays are expenditure

You have probably noticed that I tend to refer to capital outlays and operational

expenditure. This is a rather weak attempt at avoiding another ambiguity. Some

bean counters refer to them as capital and expenditure respectively. I do not know

about you, but I class handing over a cheque for an asset as spending. Using the

word outlay almost exclusively in relation to capital spending, I hope to help you

separate it from operational spending.

t

ACCOUNTING FOR FIXED ASSETS 199

Fixed assets detailed

Here is an extract summarising expected monthly spending on fixed assets,

together with the associated depreciation schedule. It helps to open this list

vertically and specify each asset that will be acquired (computer 1, computer 2,

etc.) together with some useful descriptive notes. This creates a detailed capital

spending plan to include in your business plan. If you are starting a business,

you have also created a framework for your fixed asset register and depreciation

schedule. The totals for each category can be carried forward into a summary, as

shown here.

If you are in an existing business, remember that the schedules for the new

assets will have to be merged with the schedules for previously acquired assets.

Spending dollars, whole months Sep Oct Nov Dec

Capital outlays

Machinery 0 120,000 0 0

Office equipment 36,000 36,000 0 0

Computers 0 24,000 24,000 0

… … … … …

Total 36,000 180,000 24,000 0

Depreciation schedule Term*

Machinery 60 0 0 2,000 2,000

Office equipment 36 0 1,000 2,000 2,000

Computers 24 0 0 1,000 2,000

… … … … … …

Total 0 1 000 5 000 6 000

* Term = number of months over which assets are depreciated, in this case using

the straight-line method

200 CHAPTER 9 GETTING TO NET PROFIT

The accounting entries are as follows.

1 In October you debit fixed assets – machinery $120,000 and assuming that you

paid cash, credit cash at bank by the same amount.

2 Every month commencing in November you debit $2000 (120,000 divided by 60

months) to the operating expenditure account depreciation of machinery and credit

the asset account fixed assets – depreciation of machinery with the same amount.

At the end of the first year:

the (original) booked value is $120,000;

the accumulated depreciation is $4000 (two months’ depreciation);

the written-down or net book value is $116,000; and

your operating costs for the year include $4000 in depreciation.

If the only other transaction in the year was an issue of 200,000 shares, the financial trans-

actions for September to December would be those illustrated in Figure 9.1.

Sep Oct Nov Dec

Balance sheet

End month

Assets

Cash at bank 200 000 80 000 80 000 80 000

Fixed assets – machinery 0 120 000 120 000 120 000

Less cumulative depreciation, machinery 0 0 2 000 4 000

Net book value of assets 0 120 000 118 000 116 000

Total 200 000 200 000 198 000 196 000

Liabilities and

shareholders’ equity

Paid up share capital 200 000 200 000 200 000 200 000

Profit (loss), current year 0 0 (2 000) (4 000)

Total 200 000 200 000 198 000 196 000

Profit and loss account

Whole month

Depreciation – machinery 0 0 2 000 2 000

Net profit (loss) 0 0 (2 000) (2 000)

Cash flow

Whole month

Share issue 200 000 0 0 0

Assets 0 –120 000 0 0

Total for month 200 000 –120 000 0 0

Net cash balance 200 000 80 000 0 0

Figure 9.1 Accounting for fixed assets

ACCOUNTING FOR FIXED ASSETS 201

Working life

Machines and things

A quick look through some company accounts shows that typical depreciation

periods might be 3 years for computers, 5 years for office equipment, 10 years

for some industrial machinery, 20 years for a jumbo jet and 100 years for airport

runways (I didn’t think that this last example was reasonable either).

Fitting of premises

Spending on fittings that you cannot take with you – fixed partitioning, plumbing,

cabling, decorating – is treated as freehold improvements (if you own the

premises) or leasehold improvements (if you rent). Such spending is usually

amortised over the shorter of the life of the fittings, the lease or the building.

Research and development

Spending on your research and development team and the gizmos that they

dissect is best treated as current expenditure. However, where there is clearly

identifiable spending on the specific development of a viable product, you may

charge the outlays to capital, show the total on the balance sheet as an asset

(perhaps as product X), and begin writing it off once the product is ready for

market. The amortisation might be over the period during which you will be able

to sell the product, or over a given number of units sold.

Start-up costs

Identifiable start-up costs for a new business – such as incorporation and

professional advisers’ fees and management costs – are often capitalised and

written off over between two and five years.

Goodwill

Goodwill is the difference between the market value of a business and the net

value of the assets. It represents the future cash flow that can be generated by,

for example, trading on a name or location. You cannot show in your accounts the

goodwill value that you attach to your own company. But if you are taken over, the

acquiring company can show goodwill and amortise it over up to 20 years (more

in some circumstances). It is, however, more common in Europe to charge this

directly to shareholder equity.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.