222 CHAPTER 10 FUNDING THE BUSINESS

Balance sheets and cash flow mechanics

Creating balance sheets and cash flow is very simple. In practice, you will probably work

methodically through the figures that you have produced so far – sales, capital spend-

ing, profit and loss – and create the cash flow and balance sheet from them as you go. An

alternative is to work in the other direction. To aid your understanding, we will do both.

First, consider how you create balance sheet and cash flow projections from the capi-

tal outlays and current expenditure forecasts already in your possession. There is a short

cut, but for the moment, imagine that you are going to work through your expenditure

forecast line by line. It is useful to see how the balance sheet and cash flow forecasts

shape up when you follow this long route.

You will note that spending is always financed in one of three ways.

1 You pay cash – the way that you handle this is illustrated opposite.

2 You accrue the expenditure (or take credit on an account payable) and pay it later

– see page 224.

3 You prepay the expenditure and expense it (charge it to expenses) later – see

page 225.

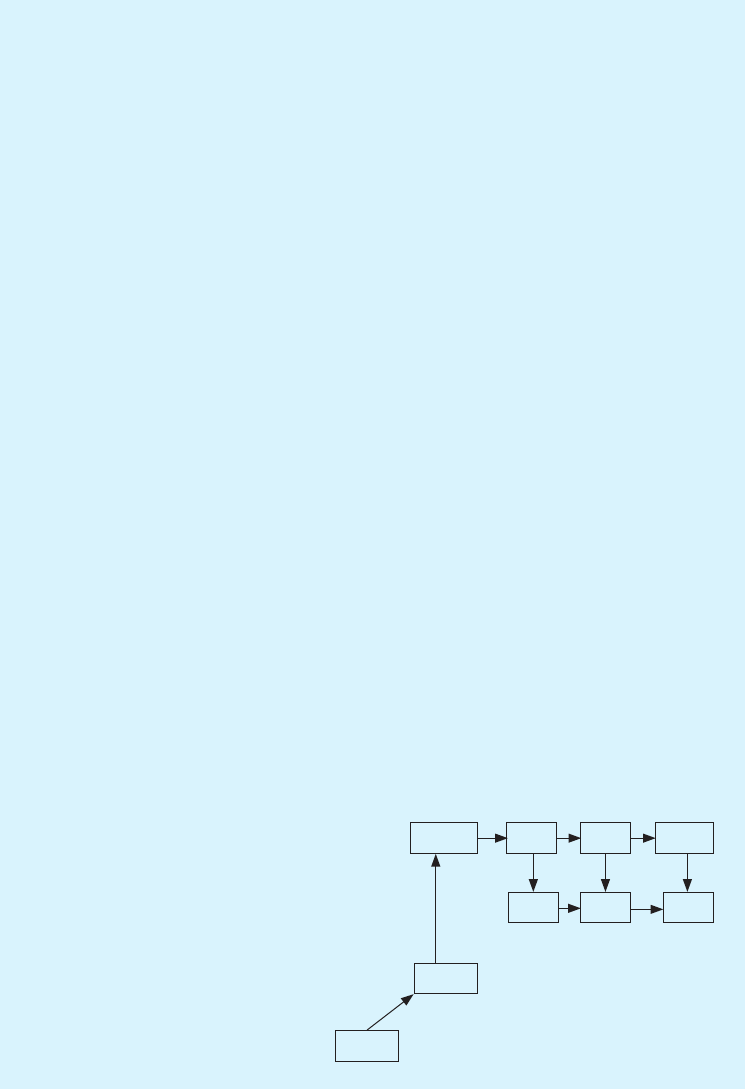

The fast track to funding

1 As an aid to your understanding, start by looking at the long way of creating

a balance sheet and cash flow projection from your capital and profit and

loss accounts. Please do not skip this groundwork unless you are already

familiar with the techniques.

2 Now to work. Copy spending on fixed assets and depreciation into the

balance sheet and cash flow projections.

3 Work through the profit and loss account, matching any non-cash entries

(prepayments, accruals, receivables and payables) into the balance sheet and

cash flow projections.

4 Enter a cash surplus as cash at bank, or a deficit as bank borrowing or capital.

5 Value the business on the basis of the future stream of income that you have

forecast.

6 Decide how to fund and cash deficit.

7 Decide if the figures are acceptable – otherwise return to revise your strategy

and operating plan.

BALANCE SHEETS AND CASH FLOW MECHANICS 223

You can allocate all your current spending to the balance sheet and cash flow state-

ments using the three techniques illustrated on pages 223–227. When you buy inventory

on credit, the entries work in the same way as an accrual, showing on the liabilities side

of the balance sheet in accounts payable instead of accruals. Accounts receivable – money

owed to you by customers – work in reverse on the asset side of the balance sheet.

Accounting for capital outlays is similar and is described on page 226. In the same way

that your balance sheet shows the total of fixed assets at a given date, so it shows the

end-period total for inventory lifted straight from your sales spreadsheet (Chapter 8).

Make sure that you understand the logic of the following procedures. But before you

rush off and use them to produce balance sheet and cash flow projections, check out the

short cuts discussed on page 227.

‘Business is many things, the least of which is the balance sheet.’

HAROLD GENEEN

Balance sheet and cash flow (1) – from cash outlays

Suppose that you projected the following spending on salaries:

Expenditure account, whole month Jun Jul Aug Sep

Salaries 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000

Salaries are normally paid in cash. Assume that this is the case here. There is a

direct cash flow implication, but (for our current discussion) no balance sheet

effect – see footnote. The matching entry created to balance the expense account

charge is as follows:

Jun Jul Aug Sep

Balance sheet, end month

No corresponding entries yet ... ... ...

Expenditure account, whole month

Salaries 12,000 12,000 12,000 12,000

Cash flow, whole month

Salaries –12,000 –12,000 –12,000 –12,000

Note: Experienced bean counters will have spotted that the cash flow is actually

also the balance sheet effect. In other words, the total cash flow will later be

reflected in the balance sheet as borrowing or as surplus cash balances.

224 CHAPTER 10 FUNDING THE BUSINESS

Balance sheet and cash flow (2) – from accruals

Moving on from the previous example, suppose that you had agreed to pay

each December an annual staff bonus equivalent to one month’s salary. Strictly

speaking, you should show one-twelfth of the bonus as an accrued expense each

month, as follows (just three months are shown):

Expenditure account, whole month ... Oct Nov Dec

Employee bonuses ... 1,000 1,000 1,000

Now put the cash flow effects around this:

1 Starting with the January figures, record a matching $1000 accrual each month

(I have only shown three months here because of space constraints).

2 By November, the accruals have reached $11,000.

3 In December, the $11,000 balance on accruals plus the $1000 expenditure

charge for the month equals the $12,000 in bonuses that have to be paid from

cash (charge $12,000 to cash flow).

This is illustrated below. The plus and minus signs might appear confusing at first

glance, until you recall from Chapter 7 that an increase in liabilities is normally

a credit entry so the sign moves the opposite way to everything else. That’s

accountancy for you. The change in the balance sheet (the flow) is added to help

clarify what is going on. The first line of figures shows end-month balances (hence

balance sheet), all the other figures are monthly flows.

Balance sheet, end month Dec Oct Nov Dec

Liabilities: accrued bonuses 9,000 10,000 11,000 0

Memo: change in month ... +1000 +1000 –11,000

Expenditure account, whole month

Employee bonuses ... 1000 1000 1000

Cash flow, whole month

Employee bonuses 0 0 0 –12,000

But that would be misleading …

Balance sheets show balances on a specific date. Remember that the bank balance,

or inventory, or any other figure, might have been very different just a few hours

before the balance was struck. Excuse me for being cynical, but I wonder if anyone

ever massages balances on purpose?

t

BALANCE SHEETS AND CASH FLOW MECHANICS 225

Balance sheet and cash flow (3) – from prepayments

Now take a look at an expenditure that is prepaid. For simplicity, use the example

shown in Chapter 7 (see page 148). This is a situation in which:

your office rent is $1000 a month;

in June you pay the $3000 advance for the calendar months of July, August

and September.

For this case, when you prepared your spending forecast you would have recorded

the following entries under operating expenditure:

Expenditure, whole month Jul Aug Sep

Office rental payments 1,000 1,000 1,000

You can put the cash flow effects around this as follows.

1 Starting with cash flow, record the $3000 outflow in June. To be true to double

entry accounting procedures, you have to add a corresponding $3000 to the

balance-sheet asset-account called prepaid rents.

2 Then you should deduct $1000 from prepaid rents in each of July, August and

September to reflect the matching charge to the expenditure account office

rents paid.

This is illustrated below, with boxes around the matching entries. The change in

the balance sheet (the flow) is added to help clarify what is going on. The first line

of figures shows end-month balances (hence balance sheet), all the other figures

are monthly flows.

May Jun Jul Aug Sep

Balance sheet, end month

Assets: prepaid rents 0 3000 2000 1000 0

Memo: change in month ... +3000 1000 1000 –1000

Expenditure account, whole month

Office rental payments ... 1000 1000 1000

Cash flow, whole month

Office rental payments –3000 ... ... ...

Start

226 CHAPTER 10 FUNDING THE BUSINESS

Balance sheet and cash flow (4) – from capital outlays

The example shows how you allocate capital outlays to the balance sheet and cash

flow projections. Returning to the example in Chapter 9 (see page 198):

1 In October you acquire a clumping machine for $120,000.

2 It has an expected life of five years (60 months).

3 You are using the straight-line depreciation method.

4 Depreciation is therefore $2000 a month for 60 months.

For these transactions, your capital expenditure projections for this year are as

follows:

Sep Oct Nov Dec

Capital outlays, whole month

Acquisitions – machinery 0 120,000 0 0

Depreciation schedule, whole month

Machinery 0 2000 2000

This is the one instance where I have made you duplicate a little effort. The

expenditure forecasts that you created form part of the profit and loss account. But

the capital outlay account and depreciation schedule can be thought of as extracts

from the balance sheet – the same information twice. I did it this way because

capital outlays are regarded with special interest and you need this extract to wave

around in the boardroom or in your bank manager’s office.

The easiest approach is to copy the capital outlays and depreciation schedule to

the balance sheet (remember that these are changes or flows and the balance sheet

shows end-month balances). You then create the matching entries. Depreciation is

matched in the expenditure account (remember that you already put it here when

you produced your expenditure forecast). The acquisition is matched in the cash

flow account. This is how:

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.