176 CHAPTER 8 GETTING TO GROSS PROFIT

How does your forecast look? Was it what you expected? Have you made any artificial

assumptions? Will the economy perform as expected? Will your competitors play by the

rules? Will your customers remain loyal? You will review these issues in Chapter 11 and

perhaps modify the forecast – or produce best- and worst-case forecasts, etc. For the

moment, assume that you have one perfect forecast. Now look at how you move on to

forecast your gross profit.

Cost of sales

Cost of sales is sometimes called cost of goods sold, but I am sure that you can cope with

this complex variation in nomenclature. Cost of sales is, how can I put this simply, the

direct cost of what you sell in any one accounting period.

For a re-seller, the cost of sales is the price paid to acquire the goods that are to be

re-sold.

In manufacturing, the cost of sales is raw materials and other supplies consumed

in making the product, plus directly attributed production wages and factory

overheads such as heat and light.

For a software company, the cost of sales might be determined as one-hundredth

of the original R&D cost for each unit sold (if lifetime sales are expected to be 100

copies of a program).

Simple services

Perhaps from time to time you will begin to think that this chapter is all about noisy

production lines and oily machines. This is because it is useful to consider the more

complex situations. If you are re-selling goods that you buy elsewhere or providing

services, your forecasting will be much more simple. Cost of sales might be nothing

more complex than your buying price including shipping – or so-many hours of

your consultants’ time at their hourly employment costs.

Some people are notoriously poor at making these calculations. If you add up

all the hours invoiced by certain professionals during their lifetimes, you might

conclude that they each must live to be several hundred years old.

t

COST OF SALES 177

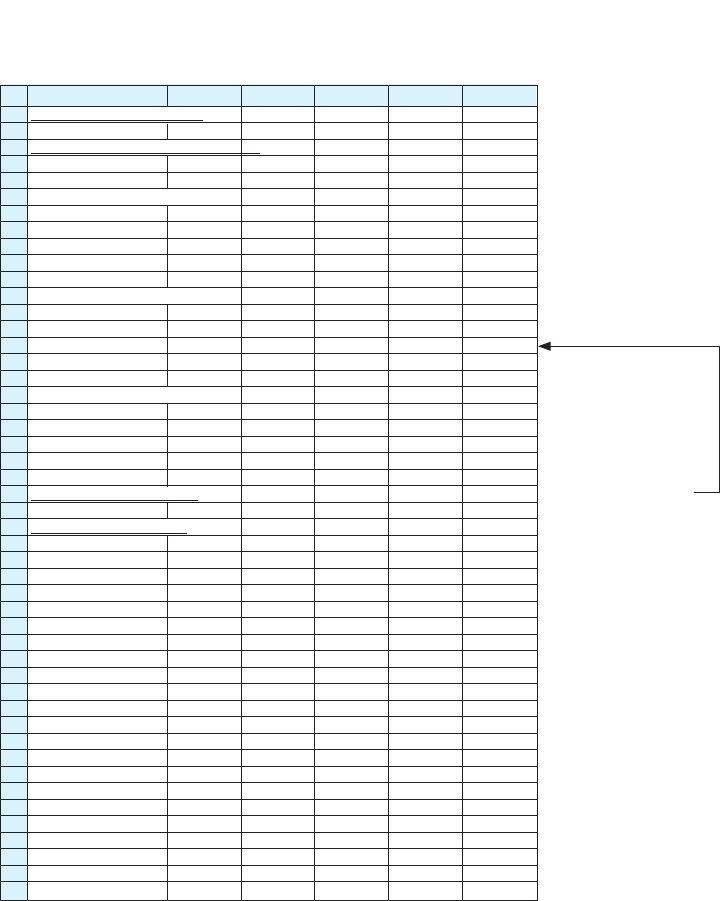

It makes sense to run through a more complex example. You can modify this or scale it

down for your own business. Figure 8.5 shows an example manufacturing account. To be

pedantic, the penultimate line perhaps belongs in a trading account but it is included to

show the final cost of sales.

It is not too hard to follow the logic. The manufacturing of a single product takes place

at a dedicated facility. It is easy to identify all the costs directly associated with produc-

tion. These comprise variable costs (such as raw materials) which vary directly with the

volume of production, and fixed costs (such as rent paid for the factory).

COST OF MATERIALS

In just the same way as you explored sales, you can analyse your raw materials, com-

ponents and other supplies. Again, look for relationships between these and various

economic indicators. This time, you are looking both at volumes – for the way that supply

and demand affect prices – and at price indicators.

Economic forecasts usually include retail or consumer price and GDP deflators – which

are indices of inflation at the consumer and national level – and exchange rates. You will

also usually find indicators of labour costs. Obviously, you can use any or all of these to

help forecast price movements in your supplies. Trade and commodity producers associa-

tions sometimes produce useful data also.

OTHER PRODUCTION COSTS

Some other production costs are shown in Figure 8.5. These are projected in exactly

the same way as any other operating costs. To avoid duplication, I will defer discus-

sion of these production and operating costs until Chapter 9. When you read it you will

understand my logic. Skip forward now if you want to get straight down to forecasting

production costs. The remaining discussion in this chapter assumes that you have already

done this.

Indirect costs cannot be directly attributed to the cost of the product. They

include R&D, marketing and sales, and other administrative costs. These

are shown sep arately in trading or operating accounts which we look at in

Chapter 9.

178 CHAPTER 8 GETTING TO GROSS PROFIT

PRODUCTION OR PURCHASING COSTS

You need to understand how much it costs to produce a unit of your product – otherwise

you would not know how much to sell it for. The unit might be one widget, one hour of

legal advice, one bed occupied (such as in a hospital or hotel), a tonne of coal, 1000 sheep

and so on.

Simplistically, divide cost of production by the number of items produced. For exam-

ple, if the $750,000 worth of activity in Figure 8.5 produced 375,000 widgets, the cost

associated with producing one widget is:

unit cost = total cost of production ÷ volume of production

= 750,000 ÷ 375,000

= $2

Sample manufacturing account

Year ended 31 December

Money

Raw materials (dollars)

Opening stock 50 000

Purchases ........250.000

300.000

Less closing stock ........40.000

Cost of materials consumed 260 000

Production wages ........150.000

Prime cost of production 410 000

Factory overheads

Packers’ wages 90.000

Management salaries 110.000

Administration salaries 50.000

Rental and property taxes 100.000

Electricity and water 12.000

Maintenance of machinery 8.000

Depreciation of machinery 10.000

Depreciation of leasehold improvements ........5.000

Total overheads .....385.000

795.000

Less increase in work-in-progress ..........5.000

Cost of goods produced .....790.000

Less increase in stock of finished goods in factory ........10.000

Cost of goods shipped to warehouse 780.000

Less increase in stock of finished goods in warehouse ......30.000

Costs of sales .....750.000

Figure 8.5 Cost of sales

COST OF SALES 179

Direct costs divide into variable and fixed. Let me state the obvious. Variable costs (such as

raw materials) vary directly with volume. Each cubic metre of concrete mix A requires, say,

1

–

2

cubic metre of gravel – and for this mix the proportion of gravel is always 50% of the

total (except in shoddy construction work when standards slip so that the contractor can

save on cement).

Figure 8.6 Playing the numbers game (2)

All of the figures here are calculated automatically from the first part of this spreadsheet, which is

shown in Figure 8.4. This spreadsheet also shows an example of the effects of using FIFO and LIFO

to value inventory when production costs are falling – see Valuing inventory on page 181.

A B C D E F

38 TETRYLUS Inc Financial plan

39

40 Sales, costs and prices, first five years

41 Dollars

42 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5

43 Hardware inventory volume

44 Opening stock 0 1 160 1 160 1 160 1 160

45 Additions (production) 5 000 42 000 330 000 450 000 600 000

46 Reductions (sales) –3 840 –42 000 –330 000 –450 000 –600 000

47 Closing 1 160 1 160 1 160 1 160 1 160

48

49 Hardware inventory value (FIFO)

50 Opening stock 0 29 000 31 900 49 880 87 232

51 Additions (production) 125 000 945 000 3 960 000 4 860 000 5 832 000

52 Reductions (sales) –96 000 –942 100 –3 942 020 –4 822 648 –5 756 043

53 Closing stock 29 000 31 900 49 880 87 232 163 189

54

55 Hardware inventory value (LIFO)

56 Opening stock 0 29 000 29 000 29 000 29 000

57 Additions (production) 125 000 945 000 3 960 000 4 860 000 5 832 000

58 Reductions (sales) –96 000 –945 000 –3 960 000 –4 860 000 –5 832 000

59 Closing stock 29 000 29 000 29 000 29 000 29 000

60

61 TETRYLUS Inc Financial plan

62

63 Gross profit, first five years

64 Dollars

65 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5

66 Gross sales

67 Hardware 307 200 2 100 000 14 850 000 18 225 000 21 870 000

68 Software 14 000 52 500 396 000 540 000 720 000

69 Total 321 200 2 152 500 15 246 000 18 765 000 22 590 000

70

71 Cost of sales

72 Hardware 96 000 945 000 3 960 000 4 860 000 5 832 000

73 Software 2 000 10 500 66 000 90 000 120 000

74 Total 98 000 955 500 4 026 000 4 950 000 5 952 000

75

76 Gross profit

77 Hardware 211 200 1 155 000 10 890 000 13 365 000 16 038 000

78 Software 12 000 42 000 330 000 450 000 600 000

79 Total 223 200 1 197 000 11 220 000 13 815 000 16 638 000

80

81 Gross profit margin %

82 Hardware 69 55 73 73 73

83 Software 86 80 83 83 83

84 Total 69 56 74 74 74

85

Source:

Line 47, previous period

Based on line 18

Line 18

Line 44 + line 45 + line 46

Line 53, previous period

Line 22 x line 45

Line 50 + line 51 + line 52

Line 59, previous period

Line 22 x line 45

Line 22 x line 46

Line 56 + line 57 + line 58

((Line 46 – line 47)

in previous period)

x line 22) + line 53

in previous period

Line 18 x line 26

Line 19 x line 27

Line 67 + line 68

Line 18 x line 22

Line 19 x line 23

Line 72 + line 73

Line 67 – line 72

Line 68 – line 73

Line 77 + line 78

Line 77 + line 67 x 100

Line 78 + line 68 x 100

Line 79 + line 69 x 100

180 CHAPTER 8 GETTING TO GROSS PROFIT

On the other hand, fixed costs are relatively fixed in relation to production. Factory rent

will not vary, whether output is zero or running at maximum capacity. Machine costs might

be fixed in relation to smaller quantities of output. If it costs you $15,000 to rent a machine

to produce anything between 0 and 100,000 units a month, the fixed costs related to the

machines go up in steps of $15,000 every time that production passes a 100,000 barrier.

When you have calculated the cost of producing a unit of your goods or services you

can multiply volumes by unit-cost to arrive at total cost of sales. For example, for 375,000

units at $2 a unit:

cost of sales = sales volume × unit-cost of production

= 375,000 × 2

= $750,000

The alternative is to do it the long way, to produce a column of figures similar to those in

Figure 8.5 for each period in your forecast. You are going to have to do this eventually for

the budget exercise – but the unit-value approach is useful for what-if analysis (what if

sales were $500? $10,000? $20,000?) and for ‘big-picture forecasting’ while you are refin-

ing your strategy and plans.

MANUFACTURING, TRADING AND OPERATING ACCOUNTS

Often, the sales and costs of sales figures are included in the overall profit and loss

account. We do it this way in Chapter 9. For complex situations, you might separate out

chunks of related numbers – otherwise you would need a very long sheet of paper (such

as the back of one of those huge computer printouts that for some reason are always

stacked up in the accounts department). You might have three accounts.

1 A manufacturing account such as in Figure 8.5.

2 A trading account. This starts with costs of goods shipped to warehouse (brought

forward from the manufacturing account) and shows sales and distribution

activities resulting in gross sales and gross profit.

For general analysis, you will want to attribute the portion of indirect costs

(such as marketing) that has to be absorbed in the production and sale

of each of your products. This is discussed in Chapter 11. For the current

purposes of assessing production costs we need consider only direct costs.

t

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.