Chapter 9. The Low-Low-High Count

“Low-Low-High Counts are usually accurate within a margin of one or two days. This is their point of superiority. Many seem to work to the exact day, or even hour.” —George Lindsay

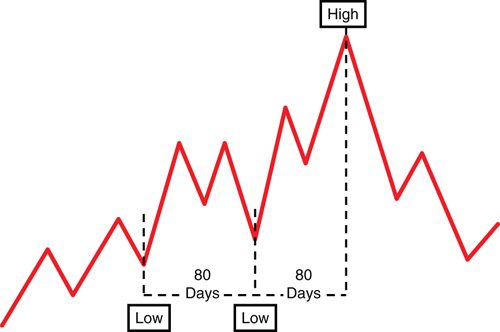

In the Lindsay Timing Method, the Low-Low-High Count (referred to as LLH) is used to confirm the 107-day Top-to-Top count. Using the LLH interval count sharpens up the 107-day count considerably by eliminating less-than-ideal 107-day counts. The concept is quite simple. One begins by first determining the number of days between any two “lows,” then counting forward the same number of days to arrive at a high (see Figure 9.1). “The indicated high may be either the last day up or the first day down.”1 The operative word in Lindsay’s quote is “indicated.” A high is not always the result of using this procedure in isolation, but even when no high is produced the method is still useful. By combining the LLH count with the 107-day count, Lindsay developed a system that does a remarkable job of predicting highs in price. Sometimes the changes in trend predicted by the model are more severe than at other times. Lindsay gave suggestions to help determine the relative degree of a sell-off an analyst should expect, and they are included at the end of this chapter.

Figure 9.1. Low-Low-High Count.

Like 107-day counts, LLH counts are made using calendar days, not trading days. When one is using calendar days, the indicated date of a high sometimes falls on a Saturday, Sunday, or holiday. To determine whether the targeted high should be expected to fall on either the day before or the day after a closed day in the market, Lindsay suggested checking by counting market days. Fortunately, it has been found that the simpler process of assuming a Friday target date for counts ending on a Saturday and a Monday target date for counts ending on a Sunday works quite well.

Determining Lows

Before the analyst can begin counting, he or she must determine from which lows the counts will be made. Like key dates in the 107-day Top-to-Top count, lows are determined by closing prices. “In deciding which day is the low, we go by closing prices with very few exceptions.” One exception Lindsay noted was for what he described as “extreme” intraday lows. Here again, he failed to define exactly what should be considered an “extreme” intraday low and depended on the reader’s judgment. At one point, he wrote that that it would “violate common sense” to call one particular day the low just because it was the closing low when an adjacent day contained an extreme intraday low.

“A count can be taken between any two lows, no matter how far apart they are, or what fluctuations take place between them. Thus, there are an enormous number of Low-Low-High counts. Since we are interested only in worthwhile downtrends, we use a small number of the total counts. They must therefore be sorted out systematically to avoid confusion.” The “system” Lindsay used to sort the lows was to differentiate between what he categorized as important lows and minor lows.

“First minor lows must be differentiated from important lows.” Minor lows are easy to identify as they are any low other than an important low. Unfortunately, Lindsay doesn’t define important lows. The closest he came to defining important lows and minor lows is when he wrote, “The distinction should be clear from glancing at the chart.” For the purposes of this book, we shall define an important low in an uptrend as a retracement that drops lower than a previous low in the uptrend prior to the most recent high (similar to finding a Key Range). An important low can also be thought of as a change in trend from down to up. As for downtrends, all the examples of important lows presented by Lindsay in downtrends appear to be forms of the “extreme” intraday lows discussed previously. He also wrote that a “violence of fluctuations” can cause an important low. A violent fluctuation would be expected to print an extreme (intraday) low. In this book, a major low in a downtrend is a low that precedes an upward retracement that climbs higher than a previous upward retracement found in the same downtrend.

Counts

Once the important lows and minor lows have been identified on a price chart, counting the intervals between lows can begin and the resulting counts and dates recorded in a log. Here, Lindsay distinguished between important counts and minor counts. He also took care to explain how long each type of count should be expected to have an effect on the market—that is, the longest interval the analyst needs to track for each type of count. There are four separate counts to be aware of: two important counts and two minor counts.

Important Counts

A count from one important low through another important low is rated as an important count. An important low has a maximum life of two years. “For that long after it is established, take counts between it and every other important low.” This means that an important low can be expected to have an effect on the market for the next four years because counting forward two years from a second important low (identified two years after the first important low) would cover a total of four years. Of course, it is only those dates that are pinpointed by the counting, and not the time between the dates, that are important to bear in mind.

A count from an important low through a minor low also rates as an important count provided that the minor low is not more than three months later. This three-month rule eliminates what could have become an overwhelming number of important to minor counts during the preceding two years.

Minor Counts

A count from one minor low through any other minor low is rated as a minor count.

A count from a minor low to an important low is also a minor count.

The number of minor counts is kept manageable by the fact that a minor low is valid for no more than four months. “During that period, take counts between it and every other low, whether important or minor.”

“Several counts are often made through the same low.” A count can be taken between any two lows no matter how far apart they are. The reader can easily imagine how this could become a terrible mess and that a spreadsheet is a necessary tool—even more so once the 107-day counts are included. One’s sanity is saved, however, by the time limits Lindsay placed on the counts.

Combining LLH Counts with 107-Day Counts

At this point, the 107-day counts have been determined, important lows and minor lows identified, and the different counts all taken and listed in a spreadsheet. Now the recorded data is examined to detect converging dates and dates within the same cluster. “At frequent intervals, compare the list with the expiration of any future Top-to-Top counts which are apparent. Retain all minor counts which expire within about a week on either side of a Top-to-Top count. Keep all important counts which expire within five or six weeks of a Top-to-Top count.” That last statement should cause the reader to pause. It would seem to invalidate the ±5-day window of the 107-day count if dates as far as five to six weeks away are to be “dates of interest.” Lindsay appeared to contradict this instruction himself when he wrote, “Low-Low-High counts are usually accurate within a margin of one or two days—unlike 107-day cycles with their 5-day window. This is their point of superiority. In all other respects, Low-Low-High counts are less important than Top-to-Top counts.” If the LLH counts are to narrow our target range from a 5-day window to a 2-day window (on either side of the target date), then it is confusing how an important count five or six weeks away should be of concern. The chief function of an LLH count tells us whether the Top-to-Top count will last 103, 107, or 111 days. This confusion is cleared up in Chapter 10, “Combining the Counts,” in a discussion of trading ranges. For now, it is important to be clear on Lindsay’s basic guidelines.

Expected Size of the Decline

“A Top-to-Top count can be used alone. A Low-Low-High count cannot. Its only value lies in the way it combines with some other count. An important Low-Low-High count should theoretically result in a bigger decline than a minor one. But the extent of the decline depends on how closely the Low-Low-High count agrees with some other count.”

To get a big decline in the market, the first requirement is that there must be a Top-to-Top count. The second requirement is that the 107-day Top-to-Top count either must approximately coincide with an important Low-Low-High Count, or, as an alternative, must expire while the average is in the same trading range. Lindsay calls this trading range a “cluster.” The third requirement to expect a big decline is that a minor count must coincide with both the major count and the 107-day count. Lindsay never explained what a “big” decline meant to him. From his writing, one can assume that he meant a decline through which an investor would prefer not to stay invested.

A mild decline can be expected with a mix of a minor count and a 107-day count. This matchup is not expected to produce a decline of interest to anyone other than the most nimble of traders.

Lindsay did suggest an exception to his rule requiring a Top-to-Top count. He wrote, “There are cases, however, when several Low-Low-High counts coincide. They may then be used without confirmation by any other kind of count.” That statement is explored more fully in Chapter 10.

Conclusion

The following is a quick summary of this chapter and can serve as a quick reference guide in the future for the reader:

The Low-Low-High Count is used to confirm the 107-day Top-to-Top count.

Important lows and minor lows must be identified and logged.

Counts must be taken between all important lows within two years of one another.

Counts are taken from all important lows to all minor lows not more than three months later.

Counts are taken between all minor lows within four months of one another.

Counts are taken from a minor low to any important lows not more than four months later.

A big decline can be expected only if a Top-to-Top count is present.

Endnote

1 Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes in this chapter are taken from George Lindsay’s self-published newsletter, George Lindsay’s Opinion, during the years 1959–72.