CHAPTER 18

PROJECT LEADERSHIP

“To be a leader of men one must turn one’s back on men.”

HAVELOCK ELLIS, 1859–1939

18.1 INTRODUCTION

Leadership has been studied and written about extensively in the twentieth century. There have been thousands of articles and papers authored about the subject. Several hundred books have also appeared that examine the function of leadership in many different forms of organizations—governmental, industrial, and political to mention a few. One of the more recent examinations of the leadership function in modern organizations is a comparison of leaders and managers. One notable researcher, Warren Bennis, described a leader as someone “who does the right thing,” and the manager as someone “who does things right.” This is an interesting viewpoint that is explored more fully in this chapter.

This chapter tries to put leadership into a project perspective. Leadership is defined; some of the principal studies of leadership are presented. The nature of a leadership style that is appropriate for leading a project team is described. Leadership is offered from the perspective of the management of attention, management of meaning, management of trust, and management of self, and should arouse the personal interest of the student and reader. Project leadership is differentiated from other forms of leadership—and the competencies that project leaders should have are described. A clear differentiation between project leaders and project managers cannot be made because that differentiation involves an understanding of a complex set of variables. As the study and publication about leadership—vis-à-vis managership—continues, perhaps the authors will be able to offer further insight into these ideas in the future.

18.2 CONCEPT OF LEADERSHIP

The concept of leadership is surely as old as the concept of organized activity. Organizations have been led with varying degrees of effectiveness by people called “leaders” since the development of organized societies. Leadership in the political, social, military, legal, economic, and technological environments has been celebrated and studied throughout history. Today these studies continue to try to understand what both separates and harmonizes leaders and followers.

Our view of a project leader is that individual who leads a project team during the project life cycle and accomplishes the project objective on time and within budget. Project leadership is defined as a presence and a process carried out within an organizational role that assumes responsibility for the needs and rights of those people who choose to follow the leader in accomplishing project results. In this chapter the concept of project leadership will be presented. But before discussing project leadership, we will present some ideas about the general nature of leadership.

18.3 WHAT IS LEADERSHIP?

There are many definitions of leadership. Fiedler cites nearly a dozen different definitions with varying connotations and degrees of emphasis on elements. He defines a leader as “the individual in the group given the task of directing and coordinating tasks in relevant group activities or who, in the absence of a designated leader, carries the primary responsibility for performing these functions in the group.”1 Peter Drucker opines that effective leadership is based primarily on being consistent.2 Arthur Jago defines leadership as both a process and a property. He states that leadership is the use of noncoercive influence to direct the activities of the members of an organized group toward the accomplishment of group objectives. He considers leadership in the context of a set of qualities or characteristics attributed to those who are perceived to successfully employ such influence.3

Jago notes that leadership is not only an attribute but also what the person does. Under this definition, then, anyone on a project team may take on a leadership role. In his research, Professor Hans J. Thamhain has identified that project management requires skills in three primary areas of abilities leadership: interpersonal, technical, and administrative. He goes further and offers some suggestions for developing project management skills needed for effective project management performance.4

The subject of leadership has received much attention, yet we do not have a universally accepted definition of the term. James McGregor Burns’s book, Leadership, cites one study with 130 definitions of the term.5 Another book notes over 5000 research studies and monographs on the subject. The editor of a handbook concludes that there are no common factors, traits, or processes that identify the qualities of effective leadership.6 Most books tend to equate leadership with a “hero person.” Others view leadership as characterized by personal characteristics such as charisma, intelligence, energy, style, commitment, and so on. Other theorists view leadership as depending on anything from task conditions to subordinate expectations.7

Literally thousands of studies have explored leadership traits. Some of the traits relate to physical factors, some to abilities, many to personality, and others to social characteristics. Of all the traits that have been described, there appears to be most support for the roles of activity, intelligence, knowledge, dominance, and self-confidence.

18.4 STUDIES OF LEADERSHIP

Other views of leadership have taken a new direction, looking not only to the individual’s traits but also to the behavior of the leader and those people who are being led. McGregor summarizes some of the generalizations from recent research on leadership, which portray “leadership as a relationship.” According to McGregor:

There are at least four major variables now known to be involved in leadership: (1) the characteristics of the leader; (2) the attitudes, needs, and other personal characteristics of the followers; (3) characteristics of the organization, such as its purpose, its structure, the nature of the tasks to be performed; and (4) the social, economic, and political milieu. The personal characteristics required for effective performance as a leader vary, depending on the other factors.

McGregor’s viewpoint is important because “it means that leadership is not a property of the individual, but a complex relationship among these variables.”8

Other approaches have explained leadership as a type of behavior, for example, dictatorial, autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire. The operating styles of these types of leaders consist of getting work done through fear (the dictator), centralizing decision making in the leader (the autocrat), decentralizing decision making (democratic leadership), and allowing the group to establish its own goals and make its own decisions (laissez-faire leadership).

Still other approaches deal with leadership as specific to the particular situation in which it occurs. Therefore, leaders have to be cognizant of the groups of people (superiors, subordinates, peers, etc.) to which they are related as well as the organizational structure, resources, goals, time variables, and so forth. This suggests the real complexities of trying to understand what leadership is all about. A basic conclusion can be drawn: Successful leaders must be adaptive and flexible, always aware of the needs and motivations of those whom they try to lead. Leaders must be aware of how they perform as leaders and how their behavior affects the performance of those on whom they depend. As leaders try to change the behavior of their people, a change in their behavior also may be needed.

Gadeken found in his research in the DOD environment that when project managers take on large, complex, or one-of-a-kind projects, technical and management skills are not sufficient to ensure leadership skills.9

Hauschildt, Keim, and Medcof, in a study of 257 successful and 191 unsuccessful projects, found that project success is much more dependent on the human factor (project leadership, top-management support) than upon project management.10

Research into the matter of leadership continues, because we really know little of what it is and why it works sometimes and fails at other times. Project managers who strive to improve their leadership abilities should read in this area of study.

18.5 LEADERSHIP STYLE

An important part of leadership is the “style” with which the leader carries out the role. Much has been written about leadership style. Also, the characteristics of successful leaders have been examined in detail. What follows is just a sample of the abundant views on the subject.

John E. Welch, Jr., former CEO of General Electric Company and a superb leader, would not tolerate autocratic, tyrannical managers in leadership positions. In a letter to shareholders, CEO Welch discussed management techniques and goals. According to him, GE “cannot afford management styles that suppress and intimidate” subordinates. Welch categorized managers into several types:

• A leader who delivers on commitments financial or otherwise and shares the values of the company has onward-and-upward prospects.

• A leader who does not meet commitments but shares the company values will get a second chance, preferably in a different environment.

• A leader who doesn’t meet commitments and doesn’t share values is soon gone from the company.

• The fourth type is the most difficult to deal with. This individual delivers on commitments, makes all the numbers, but doesn’t share the values. This individual is typically the one who forces performance out of people rather than inspires it, the autocrat, the big shot, the tyrant.

In today’s environment, where it is necessary to have good ideas from every person in the organization, those people whose management styles suppress and intimidate are not needed. GE proclaims high priorities for focusing on customers, resisting bureaucracy, cutting across boundaries, thinking globally, demonstrating enormous energy, and being able to energize and invigorate others.

GE sent many managers to observe highly successful Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., where the leadership factors of speed, the bias for action, and utter customer fixation have helped drive this high-discount store to success.11

Leadership style is in general of two types: people-centered, described as democratic, permissive, consensus-seeking, participative, follower-oriented, and considerate, and task-centered, described as structured, task-dominated, restrictive, directive, autocratic, and socially distant. Task-oriented leadership style usually is associated with productivity but may depress follower satisfaction, whereas people-centered leadership tends to enhance group cohesiveness but not consistently increase productivity.

Leaders, except for the likes of Napoleon, Alexander, or Ghengis Khan, whatever their style, all have their “superiors” to whom they must subordinate their wishes, or both they and their organization will probably fail. Managers (and leaders) who are successful in being promoted up through the organizational hierarchy have demonstrated an ability to lead their followers and to follow their superior leader. Emotionally and intellectually, a leader is wed to the conviction that an organizational unit cannot accomplish its mission without some degree of obedience at every level in the hierarchy. A leader needs obedience and discipline from followers and thus accords it to superiors. To demand obedience from one’s followers but to withhold it from higher authority would constitute an inconsistency that would jeopardize the fundamental discipline of authority-responsibility-accountability, which holds an organization together.

We have all seen or heard of mavericks, who “march to a different drummer” and cannot function in a hierarchical organization and strike out on their own. Upon leaving and starting a new “business,” these mavericks usually end up creating some form of a leader-follower organizational structure.

Effective leadership, then, is usually preceded by effective followership. A successful project leader doubtlessly has performed successfully as a follower. This success provided the basis for that individual’s opportunity to become a successful leader. Followers provide the opportunity and legitimacy to the leadership role. In the changing, complex world of project management, we believe that tomorrow’s project managers cannot successfully emerge without having learned the skills and developed the attitudes of followership.

The following examples can help emphasize the differences of leadership style depending on both the leader and the circumstances.

Peter Ueberoth, “project manager” for the 1984 Olympics, is described as having a management style that ensures that he is in control at all times. His ego and inner toughness helped him promote and successfully conclude a project with a global objective. His abilities in cultivating the stake-holders were instrumental in raising the money required for the Olympics. Ueberoth believes that a leader’s role is to inspire people to greater efforts. He believes that authority is 20 percent given and 80 percent taken. If someone faltered on his project, he made a change and put someone in who could handle the job.12

Leadership style should not necessarily be consistent in all activities. On the contrary, project leaders should be as flexible as possible, gearing their leadership style to the specific situation and the individuals involved, that is, within the key elements of any leadership situation the leader, the led, and the situation. Figure 18.1 shows a continuum of leadership behavior with the basic ingredient being the degree of authority used by a manager versus the amount of freedom left for subordinates. Autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire leadership styles can be identified across this continuum from boss-centered leadership to subordinate-centered leadership.

FIGURE 18.1 Continuum of leadership behavior. (Source: Robert Tannenbaum and Warren H. Schmidt, “How to Choose a Leadership Pattern,” Harvard Business Review, March–April 1958, p. 96. Copyright © 1958 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Reprinted by permission, all rights reserved.)

It is difficult to generalize about the characteristics of leaders. They come in all shapes, colors, and sexes. Some are brilliant, some are dull, some are articulate, some can write, some are proactive, and others are laid back. However, a few characteristics are found in leaders who have proven track records:

• They have their act together; their personal ambition drives them to succeed and the organization they are leading to succeed.

• They are visible to their people; they are not “absentee landlords.” There is no doubt in anyone’s mind that they are in charge and on top of everything.

• They are available to their people to listen, debate, and gather the necessary facts; at the same time they are ready to say, “Let’s do it.”

• They are decisive and in the long run make the decisions that turn out to be right. They know when to stop gathering information and recommendations into a decision and say, “OK, go do it.”

• They see the best in the people with whom they work, not the worst. The leaders see winners and praise and develop these winners for higher levels of performance.

• They are simplistic and avoid making things complex. Good leaders make things simple, coming at people from different approaches until people are convinced, or people convince them that this or that is the way to do things.

• They are fair and patient, and usually they have a sense of humor that tides them and their people over the rough spots that come to any enterprise. Humility is a mark found in good leaders who recognize that they are leaders only because the followers have allowed them to remain in a leadership role.

• They work hard at leadership, at providing the people with the resources needed to do the job, and follow up to see if people are doing those jobs.

18.6 MANAGEMENT VIS-À-VIS LEADERSHIP

What’s the difference between leadership and management? Management is usually considered to be a more broadly based activity including functions other than leading. According to Davis:

Leadership is a part of management, but not all of it. A manager is required to plan and organize, for example, but all we ask of the leader is that he gets others to follow. Leadership is the ability to persuade others to seek defined objectives enthusiastically. It is the human factor, which binds a group together and motivates it toward goals. Management activities such as planning, organizing, and decision making are dormant cocoons until the leader triggers the power of motivation in people and guides them toward goals.13

The factor that empowers the project team and ultimately determines which projects fail or succeed is the leadership brought to bear on the project at all levels in the enterprise. When a project is undertaken in the implementation of an enterprise strategy, the key to making that project happen is the quality of leadership. Lynn Crawford, a notable PMI member, in her research has noted that project leadership “appears consistently in the highest ranking category amongst Project Manager Competence factors.”14

Warren Bennis, a prolific writer in the field of leadership,15 offers an intriguing differentiation between these two roles: “a leader does the right thing (effectiveness); a manager does things right (efficiency).” In this context, the project leader develops the vision for the project, assembles the resources, and provides the inspiration and motivation for working with project stakeholders in doing the right thing to accomplish the project’s objectives; completing the project so that its technical performance, cost, and schedule objectives are attained and so that the project results have a place in the future of the enterprise.

Bennis’s description of leaders doing the right thing and managers doing things right is a useful way of looking at the differences between leadership and managership. Taking this difference and fleshing it out a bit, one could come up with something like the following to show the difference:

Leadership

• Finds and develops a vision for the project, and sells that vision to the project team and other stakeholders.

• Copes with operational and strategic change involving the project.

• Builds networks of interest with key stakeholders and develops strategies to ensure their support for the project.

• Sets the general direction of the project and its work.

• Provides the conditions surrounding the project that motivate and commit stakeholders to support the project.

• Watches for broad patterns and relationships that have the potential for impacting the project and leads the way to ensure that these patterns and relationships provide positive support to the project.

• Does the right thing in providing leadership of the stakeholders so that they support the project’s purposes.

• Becomes a symbol of the project and its purposes.

• Builds political support for the project among all stakeholders and other vested interests.

• Is concerned with effectiveness in the use of project resources.

Managership

• Copes with the complexity of designing, developing, and operating the management systems to support the project.

• Maintains oversight over the efficiency and effectiveness of the resources being used on the project and the management systems used to support those resources.

• Designs and executes the operation of the planning, organizing, motivating, and control functions used to support the project.

• Is concerned with order and efficiency in the use of resources on the project.

• Keeps key stakeholders informed on the progress or lack of progress being made on the project.

• Reassigns resources as needed to provide support to the project team.

• Monitors and evaluates the ability of the individuals on the project team and the team itself to contribute meaningfully to the project purposes.

• Ensures that the communication system used to support the project is working satisfactorily.

• Provides monitoring, facilitating, teaching, and other means to develop the individual and collective competencies of the project team.

• Does things right.

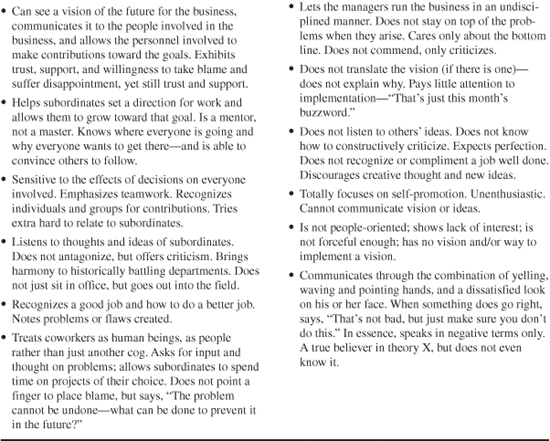

Marino opines, “Today’s mega corporations are so encumbered with rules, regulations, and traditions that they are designed to be managed rather than led.” He suggests another way of looking at the difference between managers and leaders (see Table 18.1).16

TABLE 18.1 Managers versus Leaders

Project managers must not only manage but also lead. Project leadership should be appropriate to the project situation because leadership is a continuous, flexible process. There are no consistent characteristics of leadership to point to and flatly state: “That’s what makes a leader.” Decisiveness is often cited as a desirable leadership characteristic, yet if a leader makes a wrong decision, the organization can suffer. Each management situation, the people involved, the times, the characteristics of the followers, the urgency of the decision, and so on, all influence both the leaders and the followers.

Project leadership is an interpersonal and strategic process, which seeks to influence the project stakeholders to work toward closure of the project purposes. Project leadership takes place through interaction, not in isolation.

Project managers, like most managers in modern organizations, are both leaders and followers, operating in a culture where both formal and informal networking relationships proliferate. In such relationships networking goes beyond the project manager’s formal authority, often leading to the use of influence over peers and superiors to affect the outcome of the project.

A project manager’s leadership position encompasses three fundamental roles: an interpersonal role, which includes figurehead and leader in liaison functions; an informational role, which entails disseminating information and acting as a spokesperson; and a decision-maker role, in which the project manager acts as entrepreneur, resource allocator, and negotiator.17

Project leaders are the people who do the right thing; project managers are people who do things right. Bennis recognizes that both roles are important in management, but they differ profoundly. There are, according to Bennis, people in senior positions in organizations doing the wrong thing well. Part of the fault for having people do the wrong thing may well lie with our schools of management, where we teach people to be good management technicians but we fail to train people for leadership.18 Bennis goes further to identify the competencies found in people who exhibit effective leadership in their proven track records:

• Management of attention

• Management of meaning

• Management of trust

• Management of self

We will take these competencies and adapt them to the art of project leadership.

Management of Attention

An apparent trait in most successful leaders is their ability to draw others to follow them toward a purpose. Often this purpose takes an early form of a dream or a vision. Because of the leaders’ extraordinary commitment to their dreams, they communicate a commitment, which attracts people to them. People enroll in the leaders’ visions. A project manager who is effective usually knows what he or she wants to be done on the project and reflects this in a project plan.

The first leadership competency is a set of intentions, a vision, or a direction in the sense of the project objective, goals, and strategies. A project manager who has developed a project plan has taken an important step in becoming a project leader. The project leader’s role is not merely to state the project objective, goals, and strategies, but to create a meaning for the project that team members can rally around. No matter how grand the project objective, the effective project leader must use a word, a model, or a slogan to make the vision clear to others. The project leader’s goal is to go beyond a mere clarification or explanation, to the creation of what the project objective means in satisfying a customer or owner. The project manager integrates customer facts, concepts, and needs, and project team capabilities into a meaning of the project for the project team and the stakeholders. At times the leader’s most important task may be to communicate the project’s objective to key stake-holders whose viewpoint could be supportive of, contrary to, or indifferent to the project objective.

Management of Meaning

An important responsibility of senior managers as leaders is to communicate the meaning of the project results within the strategic fit of the corporate mission. When the project team members can sense that the project is a building block in the design and execution of enterprise strategies, an important step has been made toward giving the project meaning.

To make the meaning of the project apparent to the members of the enterprise, key enterprise managers must work at communicating the vision of the project through meetings and conversations.

Management of Trust

Trust is an assured reliance on the character, ability, strength, or truth of someone or something. A project leader is someone in whom confidence is placed. An ambience of trust is essential to all organizations; the main determinants of trust are reliability and commitment. Reliability deals with the maintenance of a stable project management approach and a project culture that sets and expects high performance standards. Commitment means that the project team members, and the senior managers responsible for supporting the team, are pledged to making the project results happen. Team members want to follow a team leader they can count on, even if they disagree with the leader’s viewpoint. A project leader who shifts positions frequently stands to lose the confidence and commitment of the people. One cannot emphasize enough the significance of constancy and focus in the management of a project.

Management of Self

The first challenge most of us face is to manage ourselves. If we have knowledge and skills and are sufficiently motivated, then we stand a good chance of deploying the knowledge and skills effectively. Management of self is critical. Without it we can do more harm in a management position than good. Bennis notes:

Like incompetent doctors, incompetent managers can make life worse, make people sicker and less vital. Some managers give themselves heart attacks and nervous breakdowns; still worse many are “carriers,” causing their employees to be ill.19

Management of self means that a project leader and the team members can make mistakes, but they get those mistakes out of the way as soon as possible, learn as a result of them, and move ahead.

Project leadership can be recognized by outsiders and felt by the project team. Project leadership gives power and significance to the project effort. As noted by Bennis, in organizations with effective leaders, four themes are evident:

People feel significant. Everyone feels that he or she makes a difference to the success of the organization. The difference may be small such as the prompt delivery of potato chips to a mom-and-pop grocery store or development of a tiny but essential part for an airplane. But where they are empowered, people feel that what they do has meaning and significance.

Learning and competence matter. Leaders value learning and mastery, and so do people who work for leaders. Leaders make it clear that there is no failure, only mistakes that give us feedback and tell us what to do next.

People are part of a community. Where there is leadership, there is a team, there is a family, there is unity. Even people who do not especially like one another feel the sense of community. When Neil Armstrong talks about the Apollo explorations, he describes how a team carried out an almost unimaginably complex set of interdependent tasks. Until there were female astronauts, the men referred to this feeling as “brotherhood.” I suggest they rename it “family.”

Work is exciting. Where there are leaders, work is stimulating, challenging, fascinating, and fun. An essential ingredient in organizational leadership is pulling rather than pushing people toward a goal. A “pull” style of influence attracts and energizes people to enroll in an exciting vision of the future. It motivates through identification, rather than through rewards and punishments. Leaders articulate and embody the ideals toward which the organization strives.20

18.7 PROJECT LEADERSHIP

In any discussion of project leadership, it is essential to recognize the types of challenges found in running a project, figuring out what to do and how to manage the creation of something that currently does not exist, despite uncertainty, diversity, and an enormous number of problems and challenges, and getting a management job done through a diverse set of people despite having little direct control over most of them.

During a project manager’s first months on the job, a lot of time is spent establishing where the project is and what plans should be established to get the project moving. In addition to setting plans, effective project leaders usually allocate significant time and effort to begin developing a network of cooperative relationships with the people they believe are needed to bring the project to a favorable outcome. This networking takes up considerable time as cooperative relationships with and among the stakeholders are developed. Project leaders can use a wide variety of face-to-face methods with the stakeholders, such as:

• Doing favors for them in expectation of reciprocity

• Stressing the project manager’s role

• Encouraging and convincing the stakeholders’ identification with them

• Nurturing their professional reputation with others

• Maneuvering to make stakeholders feel they are dependent on the project manager for resources to use in their organizational elements

Project leaders can call on peers, corporate staff people, or professionals anywhere in the organization, when necessary, to support the project. Excellent project leaders ask, encourage, cajole, praise, reward, demand, manipulate, use politics, and generally work hard at motivating others through effective interpersonal skills in gaining and holding support for the project.

What should senior managers do to develop leadership capabilities in their project managers? Putting someone in the job because that person is a “good manager” can be risky. Unless the project is easy to learn, it can be difficult for an individual to learn fast enough to develop a sound leadership approach; it would also be difficult to build a project stakeholder network quickly enough to effectively manage the project. The best approach would probably be to “grow” your own project managers. These are some of the things that senior executives can do:

• Identify the emerging young professionals who show a potential for leadership and management and put them in charge of one of the many small projects usually found in an organization. This would test the potential capability of the professionals, expose them to the unstructured, ambiguous ambience of a project, and provide some experience in networking.

• Send the neophyte to a formal training course to open some vistas; however, leadership cannot be fully learned in a classroom environment. Too often courses deal with overly simplistic people relationships or suggest some tools such as time management, quantitative methodology, behavioral science, or “how to run meetings” courses, which give little insight into the realities of leading a dynamic project. Nevertheless, some formal course work would probably be useful. An alternative would be to encourage the leader-to-be to begin and continue a professional reading program on leadership. By reading several good books on leadership, at least some understanding can emerge in the reader’s mind as to what knowledge, skills, and attitudes are usually found in effective leaders.

• One of the best things that senior management can do is to maintain ongoing surveillance of the project, evaluate performance, coach the project leader when required, and ensure that contemporaneous project management techniques are being used. Indeed, senior managers can set an example of outstanding management, including the integration of the project in the design and execution of enterprise strategies.

18.8 TEAM LEADERSHIP

A recent interview with Fred Brooks, author of The Mythical Man-Month, reported in Fortune Magazine by Daniel Roth highlights some important leadership points about teams. Brooks opines, “The problems of managing people in teams have not changed, though the medium in which people are designing and the tools they are using have,” Further, he notes, “There are just more people to communicate to.”21

Brooks’ comments reflect the need to manage teams—not individuals. Managing teams takes a different approach to viewing the team as a whole rather than the parts. Establishing a single goal for the team and getting buy-in from all team members focuses on job accomplishment. Individual agendas are set aside or subordinated to the team’s goal.

When a team leader devolops a theme with the team members, the team gains an identity. This identity that is positive promotes cohesiveness in the team. An example is where one team was taking a technical course and a test answer was “gull,” a corner reflector that would intensify the radar signal return. Every team member missed the right answer. The team leader turned a negative into a positive by adopting a gull—the bird—as the team’s mascot.

NASA shuttle crews are molded into teams through joint efforts. One task is to jointly design a shoulder patch that identifies the mission flight and unifies the team in its work. Leaders defining and developing team efforts—rather than individual tasks—have a greater success rate on projects.

18.9 LEADERSHIP COMPETENCIES

Leadership competencies are critical to the success of any organization and at all levels within the enterprise. Many aspects of leadership are stated or implied in this book because they apply to all managers. Project management is a subset of the enterprise’s need for leadership at an operative level, whereas the project is defined by senior managers exhibiting leadership traits and characteristics. This section focuses on the project manager and the competencies desired for the best chance of project success.

The project manager’s success as a leader is dependent on a set of personal capabilities. The project manager should understand the technology involved in the project. The word technology is used in the sense of a method followed to achieve a practical purpose. Under this broad definition, any of the means used to provide useful products and services have a “technology” content. Engineering, science, computers, manufacturing, and after-sales service have obvious elements of technology. Government, educational, military, and ecclesiastical organizations employ elements of technology in meeting their mission and objectives. The technology involved in an engineering school is different from the technology of a school of business. Projects developed within these organizations would require a project manager who had an understanding and mastery of different technologies. A project to develop a new computer would require a different understanding of that technology than the development of a new airplane.

How much depth of understanding should the project manager have in the technology related to the project? There is a risk factor to be considered. If the project manager spends too much time keeping up with the technological details, the managerial aspects of the project could be neglected. A rule of thumb is suggested: The project manager should have enough understanding of the technology of the project to ask the right questions and know if correct answers are being given. If there are detailed or in-depth questions to be asked and answered, then the project manager should seek the guidance of the appropriate member(s) of the project team. In some cases, technological issues may be so important to the project that a task force of experts should be appointed to study the issues and make appropriate recommendations to the project manager.

Another key capability of the successful project manager is to have that blend of interpersonal skills to build the project team and to work with the team and other project stakeholders so that there is a culture of loyalty, commitment, respect, dedication, and trust. Simply stated, be a leader of the project stakeholders. The ability to work with and through people—and in so doing win their support—is crucial to the success of the project. As discussed earlier, the project manager must depend on many people from different parts of the project to support the project and to work diligently to give quality results on the work packages for which they are responsible. The ability to function as a leader within the context of an acceptable and admired interpersonal style is important. All of us tend to do better when we work with a manager or leader whom we respect, who treats us with respect and dignity, and who is a pleasant person to work with. Also remember, the single greatest cause for failure of managers is their lack of interpersonal skills, a fact that has been demonstrated many times.

An understanding of the management process is another critical skill required of the project manager. This means that the project manager must know the fundamentals of the management functions of planning, organizing, motivation, direction, and control. The fundamentals that the project manager must know, as well as the project team members, include the fundamentals outlined in this book. People who become project managers and who come from one of the technologies of the project have a particular challenge here. For example, a successful engineer who is appointed to a project manager position will usually have a strong tendency to try to keep fully abreast of engineering considerations in the project. She or he will probably tend to pay more attention to the engineering aspects of the project because that is the portion most easily understood. All that attention to engineering considerations means that less time is available for oversight of the other project work packages and less time is available to truly perform in a managerial and leadership position on the project.

The ability to see the systems context and strategic context of the project is another characteristic of the skillful project manager. This means that the project is viewed as a set of subsystems or interrelated elements. These interrelated elements operate so that actions taken on one of the elements may produce a change in any of the other elements within the total project system. For example, the model of a project management system given in Chap. 5 carries this important message: The systems framework of managing a project implies that consideration be given to myriad relationships, which have both formal and informal implications. A partial or parochial approach to the management of the project will set the stage for difficulties or at best the chance that efficiency and effectiveness will be reduced. In the systems view, the project manager should consider the probable impact of forces outside the project on the project’s outcome. In Chap. 7, the idea of project stakeholders was introduced, and the advice was given that the potential impact of stakeholder actions on the project should be one of the considerations in the planning for and execution of decisions on the project. Also, each project is part of a larger system. These larger systems include the political system, the economic system, the technological system, the legal system, the social system, and the competitive system. Within these larger systems there are always forces that can help, or hinder, or even defeat project purposes. A project manager who takes the systems approach has improved chances for identifying forces outside the project that could influence the project and its outcome.

The project manager needs to know how to make and implement decisions within the systems context of the project. Making a decision requires the management of such fundamentals as:

• Defining the problem

• Developing the information required to evaluate the decision

• Considering the alternative ways of using the resources to accomplish the project purposes

• Undertaking an explicit assessment of the risk and cost factors to be considered

• Selecting the appropriate alternative

• Developing an implementation strategy for the selected alternative

• Implementing the decision

The making of decisions is much more complex than is implied in the above fundamentals. However, if these fundamentals are used as a philosophical guide to the making and execution of decisions, the probability of having more timely and successful decisions is enhanced.

Of course, the key characteristic of the successful project manager is the ability to produce results—the delivery of the project’s technical performance results on time, within budget, and so that a contribution is made to the strategic purpose of the enterprise.

The characteristics of successful project managers/leaders are not much different from those of any manager—except that project managers/leaders must be able to put their knowledge, skills, and attitudes to work in the distinctive culture of the management of an ad hoc project. Also, it must be remembered that a project leader has to work with many different stakeholders on the project over whom he or she has no delegated authority.

Keep in mind that the project manager manages the processes involved in the project work packages arising out of the appropriate functional entities and disciplines supporting the project. As an integrator-generalist, the project manager provides a focus and synergy for the totality of the project work packages—the embodiment of the work packages of the project into an entity that supports organizational strategic purposes. Indeed, the project manager is the general manager of the project as far as the enterprise is concerned.

Leaders come in all sizes, shapes, and colors. Although leadership has been exhaustively studied, we still are able to make only some generalizations about its process and attributes. Every person who has responsibility for other people has a leadership role to play. The style of leadership depends on the leader, those being led, and the environment. In general, some of the key characteristics of successful leaders are known.

By drawing on Warren Bennis’s ideas, we define project leaders as those people who do the right thing (selecting the objectives, goals, and strategies) and project managers as those who do things right (building the project team and making it work). A person who manages a project should be both a leader and a manager, developing competencies in the management of attention, meaning, trust, and self.

What are some of the modus operandi of a successful project manager or project leader? And for the aspiring project-manager-to-be, how can these characteristics and manner be developed in the individual? Indicated below are a few of the more important desirable characteristics and the manner of the successful project manager.

First, a capability to conceptualize the likely deliverables of the project—particularly in providing something of value to the customer and translating those deliverables into the technical performance objective of the project—usually expressed in a product, service, or organizational process needed by a customer. This capability may first express itself in the context of the development of a vision for the project, later to be transferred into a technical performance objective for the project and supported by meaningful and accurate cost and schedule estimates.

Second, an optimistic attitude that prevails and causes the project manager to deal effectively with the bad news and fear of failure that buffets any project. Many successful people have traveled a path to success that has had many opportunities for failure. For those who endure, a failure is looked at as a stepping-stone to improvement followed by success. It has been said that the person who knows failure has a better chance of success and that failures enable us to learn and move to successful ventures in our lives.

Third, having a tough skin and accepting the inevitable faultfinding or blame that can come in the management of a project. This is not the normal constructive criticism that is to be expected in the management of a project because stakeholders view the project from their parochial perspective and hope to influence the project work to their advantage. A project manager who does not find some griping about the project should be suspicious, because any strategy in the management of a project can be criticized.

Fourth, to empower the project team members and, as appropriate, the project stakeholders as well. For the project team policies, procedures, and linear responsibility charts are ways to delegate the authority to the team members to empower them to perform their best on the project work.

Fifth, the ability to assume risks in the management of the project. A development project for a new product, service, or organizational process has risk and the more the state of the art is being pushed, the higher the risk. Life is full of risks as individuals drive our highways, fly on airlines to attend project meetings, or negotiate contracts with vendors and subcontractors. What is important is the ability to study and discern the principal risks endemic to the project and be able to identify those experts who can properly assess and evaluate the risks and work with other experts in designing a strategy to reduce or eliminate the risk. Risks are always with us, and creativity and innovation are the handmaidens of risk.

Sixth, the ability and the courage to make decisions involving the project. The “buck” stops with the project manager, who has the authority and responsibility to make the decisions involving the project, which includes the inevitable trade-offs involved in the use of resources. Of course, some decisions may not be the prerogative of the project manager—such as the decision to terminate a project before it is completed because of a lack of “strategic fit” in the enterprise. However, the successful project manager is one who should recommend decisions by a higher authority if needed in the management of the project and help motivate those in higher levels of the organization who need to make a decision involving the project. To fail to make a decision is a decision in itself—that is, to do nothing—with the risk of continuing to use resources without any rationale for such use because someone is procrastinating on her or his decision responsibility.

Seventh, tenacity—or persistence in holding to a position regarding the project. Of course, tenacity regarding the project can be carried too far. Most innovative products are the result of many failures by the developers, but those who have unusual perseverance and toughness in sticking to their work and objectives eventually come forth with a winner. Tenacity can bridge the gap between dreams and reality.

Eighth, the ability to mentor, teach, coach, and guide the people using resources on the project. This means that the project manager is less of a manager and more of a facilitator who works as a focal point with the team members—and other stakeholders—to pull everything on the project. This means that the project manager is a role model in these matters and sets the stage for the members of the project team to carry out their responsibilities through mentoring, teaching, and coaching the people who work on the project work packages.

18.10 TO SUMMARIZE

Some of the major points that have been expressed in this chapter include:

• There have been many studies about leadership. In the last few years several writers have tried to differentiate between what a leader does and what a manager does.

• There have been many definitions of leadership. Literally thousands of studies have explored leadership traits.

• McGregor’s viewpoint of leadership is important because he states that leadership is not a property of the individual but a complex relationship among many variables.

• Effective leadership is interdependent with effective followership.

• The leadership style practiced by an individual may not be considered in all activities.

• A few manager and leader characteristics are presented in this chapter that are found in leaders who have proven track records.

• Bennis notes that a leader does the right thing and a manager does things right. In this chapter, a few differences between leadership and managership were described.

• Project leadership is an interpersonal process that seeks to influence the project stakeholders to work toward closure of the project purposes.

• The project manager’s success as a leader is dependent on a set of personal capabilities.

• In this chapter, a few of the more important desirable characteristics and the manner of the successful project manager were presented.

• Leaders have existed in human affairs ever since people banded together for some common purpose.

• In modern organizations where traditional and nontraditional project teams are used, there are many opportunities for individuals to try out their leadership abilities.

• A critical leadership role that the project manager must carry out is that played with the project stakeholders. Keeping these individuals and organizations informed of what is going on with respect to the project will make it easier to call on them when their support is needed for the project purposes.

• It is important that members of the project team understand the difference between what a leader does and what a manager does so that they can support the project manager as he or she carries out these roles.

• In recent times, there is a growing interest in examining the differences and similarities between project managers and project leaders.

18.11 ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

The following additional sources of project management information may be used to complement this chapter’s topic material. This material complements and expands on various concepts, practices, and the theory of project management as it relates to areas covered here.

• Steven W. Flannes and Ginger Levin, Essential People Skills for Project Managers (Vienna, VA: Management Concepts, 2005). The authors discuss the important aspects of a project manager’s job in dealing with people and the many variables in managing humans in a project environment. The book recognizes and addresses the need to improve “people skills” in an ever-changing project that is often managed by a highly technical person accustomed to working with machines.

• Jeffrey K. Pinto, “The Elements of Project Success”; Timothy J. Kloppenborg, Arthur Shriberg, and Jayashree Vekatraman, “The Tasks of Project Leadership”; R. Max Wideman, “How to Motivate All Stakeholders to Work Together” and Robert Yourzak, “Motivation in the Project Environment,” Chaps. 2, 15, 17, and 21, in David I. Cleland (ed.), Field Guide to Project Management, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004).

• Roger Gill, Theory and Practice of Leadership (London: Sage Publications, 2006). The author provides a comprehensive and critical review of major theories of leadership to define a more holistic understanding of leadership. This book contains illustrative examples and cases to better relate the theories and practices of leadership.

• Robert N. Lussier, Leadership, 2nd ed. (Toronto, Ontaris: South-Western, 2006). The author explains a three-pronged approach to leadership, concentrating on theory, application, and skill development to create a practical guide. This book covers the traditional theory of leadership, application of critical thinking skills and skill-building exercises.

• George Manning and Kent Curtis, The Art of Leadership (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005). The authors explore leadership development by blending behavior theory, practical application, and personalized learning. The book addresses concepts and principles of leadership as a means of learning and development of leadership skills.

18.12 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Discuss the various definitions of leadership. What traits embody these definitions?

2. What are some of the approaches used in researching leadership? How do these differ?

3. Why has leadership been so difficult to define?

4. Leadership style should not necessarily be consistent in all activities. Explain.

5. Discuss some of the personal characteristics of successful project leaders.

6. What is the difference between leadership and management? What characterizes each?

7. Discuss the fundamental roles of a project manager’s leadership position. How do these roles interact?

8. What is meant by management of attention, management of meaning, management of trust, and management of self?

9. Discuss the four themes that are often evident in organizations with effective leaders.

10. How can project managers establish a network among project stakeholders? Why is this network so important?

11. Discuss the participatory approach to project management. What assumptions define participative management?

12. Discuss some of the characteristics of successful leadership that are documented in the literature.

18.13 USER CHECKLIST

1. How does your organization define leadership? What traits characterize successful leaders in your organization? Explain.

2. How does your organization build leaders? Are young professionals given the opportunity to learn project management and leadership?

3. What style do leaders of your organization use? Is this style effective? Why or why not?

4. Do the project managers of your organization change their leadership styles to fit various activities? How?

5. Do the managers in your organization understand the difference between leadership and management? Do they develop skills in both areas? Explain.

6. Do project managers in your organization demonstrate competencies in management of attention, meaning, trust, and self? Why or why not?

7. Are the four themes, which are evident in organizations with effective leaders, evident in your organization? Explain.

8. Do the project managers in your organization form networks with project stakeholders? How?

9. What participatory approaches to management are used in your organization? Are these effective leadership tools? Explain.

10. Which of the core dimensions for effective project management are apparent in the leaders of your organization?

11. Where do the project managers and other managers of your organization fall in Table 18.2?

TABLE 18.2 Good and Poor Project Leaders

12. How would you judge the overall effectiveness of the leadership in your organization? What could be done to improve the leadership process?

18.14 PRINCIPLES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1. Project leadership is a presence and process carried out in the context of a project.

2. There is not a universal definition of leadership.

3. Project leadership is not a property of the project leader, but a complex relationship among the many variables found in the project stakeholder community.

4. The project leader’s style strongly influences the manner in which the project stakeholders perceive such a leader.

5. Effective leadership is usually preceded by effective followership.

6. There are distinct characteristics found in leaders who have proven track records.

7. A leader does the right thing; the manager does things right (attributed to Warren Bennis).

8. The project leader’s success is dependent to a large degree on a set of personal capabilities.

9. In modern organizations there are abundant opportunities for individuals to try out their leadership capabilities.

18.15 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SITUATION—BEING A PROJECT LEADER

At a meeting of experienced senior project managers in a large “systems” company, chaired by the author, nine of the participants were asked to write down a phrase, word, or sentence describing the characteristics of good project leaders whom they had encountered in their careers. Another eight of these project managers were asked to describe the characteristics of poor project leaders they had known in their careers. The responses of these project managers are shown in Table 18.2. The contrast between good and poor project leaders is evident. You, the reader, should ask yourself how you would describe your own leadership style—and whether you fall under the good or poor leadership column.

18.16 STUDENT/READER ASSIGNMENT

The students-readers should ask how they would describe their own leadership style. Would they fall under the good or poor leadership column?